Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Case of Cojocaru v. Romania

Загружено:

orizontul pascaniАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Case of Cojocaru v. Romania

Загружено:

orizontul pascaniАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

THIRD SECTION

CASE OF COJOCARU v. ROMANIA

(Application no. 32104/06)

JUDGMENT

STRASBOURG

10 February 2015

This judgment will become final in the circumstances set out in Article 44 2 of the

Convention. It may be subject to editorial revision.

COJOCARU v. ROMANIA JUDGMENT

In the case of Cojocaru v. Romania,

The European Court of Human Rights (Third Section), sitting as a

Chamber composed of:

Josep Casadevall, President,

Luis Lpez Guerra,

Jn ikuta,

Dragoljub Popovi,

Kristina Pardalos,

Valeriu Grico,

Iulia Antoanella Motoc, judges,

and Stephen Phillips, Section Registrar,

Having deliberated in private on 20 January 2015,

Delivers the following judgment, which was adopted on that date:

PROCEDURE

1. The case originated in an application (no. 32104/06) against Romania

lodged with the Court under Article 34 of the Convention for the Protection

of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (the Convention) by a

Romanian national, Mr Ctlin Petric Cojocaru (the applicant), on

16 June 2006.

2. The applicant was represented by Mr D. Afloroaiei, a lawyer

practising in Iai. The Romanian Government (the Government) were

represented by their Agent, Ms C. Brumar, of the Ministry of Foreign

Affairs.

3. The applicant alleged that his right to freedom of expression had been

infringed by the criminal courts, which had convicted him of defamation for

an article he had written about the local mayors activities.

4. On 21 May 2012 the application was communicated to the

Government.

THE FACTS

I. THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE CASE

5. The applicant was born in 1971 and lives in Pacani.

6. The applicant is a journalist and chief editor of the local weekly

magazine, Orizontul.

7. The applicant wrote an article about R.N., the mayor of Pacani,

which appeared in the 15-21 February 2005 edition of that magazine under

COJOCARU v. ROMANIA JUDGMENT

the headline Resignation of honour, listing ten points advocating the

mayors resignation. The article contained references to the mayors

activities, with wording such as Twenty years of local dictatorship;

[R.N.] at the peak of the pyramid of evil; in Pacani, only those who

subscribe to [R.N.]s mafia-like system can still do business; we have

been ruled for over twenty years by a former communist who still has the

reflexes of a county chief secretary; and [R.N.] does not represent the

interests of the [local community].

8. On the same page, the applicant wrote a news piece about an

investigation into the mayors activities. He quoted a statement by a

politician about an ongoing investigation into some of the mayors activities

by the prefectural standards board. The article also contained a statement by

another politician and the mayors point of view on the investigation.

9. On 14 March 2005 R.N. lodged a criminal complaint with the Pacani

District Court, accusing the applicant of insult and defamation. He also

sought civil damages.

10. On 19 December 2005 the court convicted the applicant of

defamation and ordered him to pay a criminal fine of 10,000,000 Romanian

lei (ROL) and to pay to R.N., together with the publishing company,

ROL 30,000,000 in compensation for non-pecuniary damage. It acquitted

him of the accusations of insult.

11. The court noted that the applicant had submitted official documents

proving that there had been irregularities in the activities of the public

administration, but considered that that proof alone was not sufficient to

justify making those statements of fact. The court reiterated that a journalist

had a general obligation to act in good faith:

Although irregularities have been found in the activity of the Pacani Agency for

the Administration of Markets, this fact alone did not entitle the applicant to write that

the victim was a Mafioso who received bribes from businessmen in order to create

facilities for them, as there is no evidence to support these statements.

According to the Code of Press Ethics the right to freedom of expression comes with

duties and responsibilities, the journalists having an obligation to act in good faith, in

order to provide accurate and credible information.

In establishing the sentence, the court took into account the applicants

criminal record, as he had previously been convicted of insult and

defamation.

12. The applicant appealed on points of law, arguing, in particular, that

the statement that had brought about his conviction was not an imputation

of a crime, as required for the existence of calumny. Moreover, he pointed

out that he had not written the sentence quoted by the District Court, namely

that the mayor was a Mafioso who received bribes from local businessmen.

13. In a final decision of 27 April 2006 the Iai County Court upheld the

previous decision. The court of appeal confirmed the lower courts finding

and explained that the expression subscribe to ... a mafia-like system was

COJOCARU v. ROMANIA JUDGMENT

defamatory of the victim. It further reiterated the journalists obligation to

act in good faith, and took the view that in not limiting his assertions to

what was necessary to inform the public, the applicant had made value

judgments intended to defame the mayor. It also noted that the applicant had

failed to abide by the warnings given to him by way of previous convictions

for similar facts and had persisted in his criminal behaviour.

II. RELEVANT DOMESTIC LAW

14. The relevant provisions of the Civil and Criminal Codes concerning

insult and defamation and liability for paying damages, in force at the

material time, as well as the subsequent amendments to them, are described

in Cumpn and Mazre v. Romania ([GC], no. 33348/96, 55-56,

ECHR 2004-XI) and Timciuc v. Romania ((dec.), no. 28999/03, 12 October

2010).

THE LAW

I. ALLEGED VIOLATION OF ARTICLE 10 OF THE CONVENTION

15. The applicant complained that the criminal sentence imposed on him

amounted to a breach of his freedom of expression guaranteed by Article 10

of the Convention, which reads as follows:

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include

freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without

interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This Article shall not

prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema

enterprises.

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities,

may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are

prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of

national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or

crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or

rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence,

or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

A. Admissibility

16. The Court notes that the application is not manifestly ill-founded

within the meaning of Article 35 3 (a) of the Convention. It further notes

that it is not inadmissible on any other grounds. It must therefore be

declared admissible.

COJOCARU v. ROMANIA JUDGMENT

B. Merits

1. The parties position

17. The Government accepted that the court decisions rendered against

the applicant constituted interference with his right to freedom of

expression, but argued that the interference was provided for by law,

notably Articles 206 of the Criminal Code and 998-999 of the Civil Code,

and had pursued the legitimate aim of protecting the victims reputation.

They further contended that the courts had given sufficient reasons to justify

the conviction. As for the applicants conduct, they considered that he had

acted in bad faith with the intention of denigrating the victim and had

presented no evidence to justify the accusations made, thus failing to

observe press ethics. They relied on Flux v. Moldova (no. 6) (no. 22824/04,

29 July 2008) and Constantinescu v. Romania (no. 28871/95,

ECHR 2000-VIII).

Lastly, the Government considered that the penalty was proportionate.

18. The applicant submitted belated comments without providing any

justification for his failure to observe the time-limits set by the Court. For

those reasons, his observations were not admitted to the file.

2. The Courts assessment

19. The Court notes that the parties agree on the existence of an

interference with the applicants right to freedom of expression. It is

satisfied that the interference pursued the legitimate aim of protection of the

rights of others.

It remains to be ascertained whether the interference was necessary in a

democratic society.

(a) General principles

20. The Court makes reference to the general principles established in its

case-law concerning freedom of expression (see, among other authorities,

Cumpn and Mazre, cited above, 88-91), in particular the protection

afforded to journalists who cover matters of public concern and that

afforded to civil servants reputations (see Busuioc v. Moldova,

no. 61513/00, 56-62, 21 December 2004; Stngu and Scutelnicu,

no. 53899/00, 40-42 and 52-53; and July and Sarl Libration v. France,

no. 20893/03, 60-64) or politicians (see Lingens v. Austria, 8 July 1986,

42, Series A no. 103, and Incal v. Turkey, 9 June 1998, 54, Reports of

Judgments and Decisions 1998-IV).

21. The Court reiterates in particular that, in matters of freedom of

expression, its task, in exercising its supervisory jurisdiction, is not to take

the place of the competent national authorities but rather to review under

Article 10 the decisions they delivered pursuant to their power of

COJOCARU v. ROMANIA JUDGMENT

appreciation. The Court will look at the interference complained of in the

light of the case as a whole and determine whether the reasons adduced by

the national authorities to justify it are relevant and sufficient and whether

it was proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued. In doing so, the Court

has to satisfy itself that the national authorities applied standards which

were in conformity with the principles embodied in Article 10 and,

moreover, that they relied on an acceptable assessment of the relevant facts

(see, among many other authorities, Lindon, Otchakovsky-Laurens and July

v. France [GC], nos. 21279/02 and 36448/02, 45, ECHR 2007-IV).

22. The Court further emphasises that although the press must not

overstep certain bounds, particularly as regards the reputation and rights of

others, its duty is nevertheless to impart in a manner consistent with its

obligations and responsibilities information and ideas on all matters of

public interest. Not only do the media have the task of imparting such

information and ideas, but the public also has a right to receive them (see

Cumpn and Mazre, cited above, 93; and Salumki v. Finland,

no. 23605/09, 46, 29 April 2014 with further references). Moreover, the

Convention provisions securing this right apply not only to information or

ideas that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a

matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the

State or any sector of the population. Such are the demands of pluralism,

tolerance and broadmindedness, without which there is no democratic

society (see, notably, Handyside v. the United Kingdom, 7 December 1976,

49, Series A no. 24, and, more recently, Mouvement ralien suisse

v. Switzerland [GC], no. 16354/06, 48, ECHR 2012 (extracts)).

23. The safeguard afforded by Article 10 to journalists in relation to

reporting on issues of general interest is subject to the proviso that they act

in good faith in order to provide accurate and reliable information in

accordance with the ethics of journalism. In addition, the Court is mindful

of the fact that journalistic freedom also covers possible recourse to a degree

of exaggeration, or even provocation (see Bladet Troms and Stensaas

v. Norway [GC], no. 21980/93, 65, ECHR 1999-III).

24. In Von Hannover v. Germany (no. 2) and Axel Springer AG

v. Germany, the Court defined the Contracting States margin of

appreciation and its own role in balancing the right of freedom of expression

against the right to respect for private life (see Von Hannover v. Germany

(no. 2) [GC], nos. 40660/08 and 60641/08, 104-07 and 109-13,

ECHR 2012; and Axel Springer AG v. Germany [GC], no. 39954/08,

85-88 and 89-95, 7 February 2012).

25. In addition, the Court reiterates that the limits of acceptable criticism

are wider as regards a politician as such than as regards a private individual.

Unlike the latter, the former inevitably and knowingly lays himself open to

close scrutiny of his every word and deed by both journalists and the public

at large, and he must consequently display a greater degree of tolerance (see

COJOCARU v. ROMANIA JUDGMENT

Lindon, Otchakovsky-Laurens and July v. France [GC], nos. 21279/02 and

36448/02, 46, ECHR 2007-IV).

(b) Application of those principles to the present case

26. The Court notes that in the case at hand the applicant reported on

matters of public concern, namely the activities undertaken by the mayor, a

public figure, and referred strictly to the acts performed in his official

capacity and not to his private life (see, mutatis mutandis, Cumpn and

Mazre, cited above, 95).

27. The Court notes that the supposed defamatory allegation, which led

to the applicants conviction by the District Court (namely that the

concerned person was a Mafioso who received bribes from businessmen),

did not exist in the original article. Moreover, the domestic courts were not

consistent on whether the defamatory allegations constituted statements of

fact (first-instance court; see paragraph 11 above) or value judgments

(appeal court; see paragraph 13 above). It reiterates that from the standpoint

of Article 10, the main difference between statements of fact and value

judgments lies in the degree of factual proof which has to be established

(see Scharsach and News Verlagsgesellschaft v. Austria, no. 39394/98,

40, ECHR 2003-XI).

28. In the present case it notes that the applicant presented evidence to

support his statements in the form of official reports revealing irregularities

in the local administration, thus in the mayors realm of activities. The first

instance court admitted that there was evidence, but not sufficient to support

the applicants expression.

29. However, the degree of precision required for establishing the

well-foundedness of a criminal charge by a competent court can hardly be

compared to that which ought to be observed by a journalist when

expressing his opinion on a matter of public concern (see Ungvry and

Irodalom Kft v. Hungary, no. 64520/10, 56, 3 December 2013). The latter

should therefore not be bound by the same standards of accuracy and

precision as a criminal investigator. Therefore, the evidence relied on by the

applicant should not have been expected to prove the mayors criminal guilt,

in particular for a crime that the applicant himself did not mention expressly

in his article (bribery), but to offer a reasonable fundament for his criticism.

30. The Court is therefore satisfied that the applicant, as a journalist

dealing with a matter of general interest, offered sufficient evidence in

support of his statements criticising the mayor of Pacani, whether they

were deemed to be of a factual nature or judgment values.

31. Furthermore, while it does not deny that some of the statements in

the article were provocative, the Court notes that the language used was not

particularly excessive (see Dalban v. Romania [GC], no. 28114/95, 49,

ECHR 1999-VI).

COJOCARU v. ROMANIA JUDGMENT

32. In examining the article closely, it is difficult to affirm that the

applicant acted with the intention of defaming R.N. (see Stngu and

Scutelnicu, cited above, 51). The reasoning in the domestic court decisions

does not offer sufficient guidance in establishing such an intention. The

Court considers that the mere fact that the applicant had received similar

convictions in the past is not an indicator of lack of good faith in the present

case, in particular as the compatibility of those past convictions with the

requirements of Article 10 cannot be assessed (see paragraphs 11 and 13

above). It notes that the applicant relied on official reports and presented the

mayors point of view on the matter in the same article (see paragraphs 8

and 11 above and, conversely, Flux, cited above, 29). Those elements

enable the Court to conclude that the applicant acted in good faith for the

purpose of Article 10 of the Convention.

33. Lastly, as to the severity of the sentence, the Court notes that the

applicant received a criminal conviction, which was entered in his criminal

record. The amounts he had to pay for the fine and damages amounted to

about EUR 1,200, representing four times the average monthly income in

Romania.

34. Having regard to the lack of a convincing explanation as to why the

official reports provided by the applicant were not sufficient to justify his

having written the article and to the lack of a proper examination of the

applicants good faith, the Court considers that the domestic courts did not

put forward relevant and sufficient arguments capable of justifying the

interference suffered by the applicant (see paragraph 21 above and

Von Hannover v. Germany (no. 2), 107, and Axel Springer AG, 88,

judgments cited above). The national authorities therefore failed to strike a

fair balance between the relevant rights and related interests.

35. The interference complained of was thus not necessary in a

democratic society within the meaning of Article 10 2 of the Convention.

There has accordingly been a violation of Article 10 of the Convention.

II. APPLICATION OF ARTICLE 41 OF THE CONVENTION

36. Article 41 of the Convention provides:

If the Court finds that there has been a violation of the Convention or the Protocols

thereto, and if the internal law of the High Contracting Party concerned allows only

partial reparation to be made, the Court shall, if necessary, afford just satisfaction to

the injured party.

37. The applicant did not submit a claim for just satisfaction or costs and

expenses within the prescribed time-limit (see paragraph 18 above).

Accordingly, the Court considers that there is no call to award him any sum

under Article 41 (see Novovi v. Montenegro and Serbia, no. 13210/05,

62, 23 October 2012).

COJOCARU v. ROMANIA JUDGMENT

FOR THESE REASONS, THE COURT, UNANIMOUSLY,

1. Declares the application admissible;

2. Holds that there has been a violation of Article 10 of the Convention;

3. Dismisses the applicants claim for just satisfaction.

Done in English, and notified in writing on 10 February 2015, pursuant

to Rule 77 2 and 3 of the Rules of Court.

Stephen Phillips

Registrar

Josep Casadevall

President

Вам также может понравиться

- Memoriu Spital CF PascaniДокумент2 страницыMemoriu Spital CF Pascaniorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

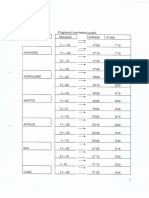

- Grafic CurseДокумент2 страницыGrafic Curseorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- 222Документ11 страниц222orizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Studiu Impact Amenajare Cimitir PascaniДокумент35 страницStudiu Impact Amenajare Cimitir Pascaniorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- BITДокумент2 страницыBITorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- REZULTATE Referendum Colegiu 5Документ1 страницаREZULTATE Referendum Colegiu 5orizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Pr. HCL 13Документ7 страницPr. HCL 13orizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Liste Ragcl Pascani Plata Locuri de VeciДокумент67 страницListe Ragcl Pascani Plata Locuri de Veciorizontul pascani100% (1)

- Cerere Comisie UrbanismДокумент1 страницаCerere Comisie Urbanismorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Manual A7Документ120 страницManual A7orizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- LocuriДокумент36 страницLocuriorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Locuri de Munca Vacante 22.08.-29.08.2018Документ36 страницLocuri de Munca Vacante 22.08.-29.08.2018orizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Plan Tarifar HCL PascaniДокумент5 страницPlan Tarifar HCL Pascaniorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Anunt Concurs Spital ManagerДокумент17 страницAnunt Concurs Spital Managerorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- NUMERE-DE-INMATRI (2) Lista Taxiurilor in Regula Din Muncipiul PascaniДокумент1 страницаNUMERE-DE-INMATRI (2) Lista Taxiurilor in Regula Din Muncipiul Pascaniorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Pr. HCL Instituire Taxa Salubrizare in PascaniДокумент7 страницPr. HCL Instituire Taxa Salubrizare in Pascaniorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- A7Документ96 страницA7mrbkenОценок пока нет

- Tarife Servicii RagclДокумент4 страницыTarife Servicii Ragclorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- REZULTATE - Col 5 DeputatДокумент1 страницаREZULTATE - Col 5 Deputatorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Program Iluminat Public PDFДокумент2 страницыProgram Iluminat Public PDForizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Lista Restante ApaДокумент6 страницLista Restante Apaorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Proiect Plagiat Paza ScoliДокумент8 страницProiect Plagiat Paza Scoliorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- New Doc 3Документ1 страницаNew Doc 3orizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Program Iluminat Public PDFДокумент2 страницыProgram Iluminat Public PDForizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Președinții Secții Votare PașcaniДокумент4 страницыPreședinții Secții Votare Pașcaniorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Lista Datornicilor La RAGCL Pascani - Persoane JuridiceДокумент5 страницLista Datornicilor La RAGCL Pascani - Persoane Juridiceorizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- New Doc 3Документ1 страницаNew Doc 3orizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- 30.09-07.10.2015 Locuri de MuncaДокумент20 страниц30.09-07.10.2015 Locuri de Muncaorizontul pascani0% (1)

- Dac Pascani - C4Документ3 страницыDac Pascani - C4orizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Dac Pascani - C5Документ3 страницыDac Pascani - C5orizontul pascaniОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Campanilla Lectures Part PDFДокумент8 страницCampanilla Lectures Part PDFJose JarlathОценок пока нет

- Defamation Law in India: Balancing Freedom of Speech and Protection of ReputationДокумент18 страницDefamation Law in India: Balancing Freedom of Speech and Protection of Reputation18223 AMOGH MITTALОценок пока нет

- Sample Summary Judgment MotionДокумент12 страницSample Summary Judgment Motionapi-293779854Оценок пока нет

- Lubiano Vs GordollaДокумент2 страницыLubiano Vs GordollaDaniela Erika Beredo Inandan100% (1)

- Cyber Crime (Speech)Документ20 страницCyber Crime (Speech)YEEMAОценок пока нет

- 2crim Law 1 Case DigestДокумент29 страниц2crim Law 1 Case DigestJoey AusteroОценок пока нет

- Regional Trial Court - Judicial RegionДокумент2 страницыRegional Trial Court - Judicial RegionAlyssa Mari ReyesОценок пока нет

- Ipc LawsДокумент324 страницыIpc Lawsbhupesh1986Оценок пока нет

- Atty. Gacayan BILL OF RIGHTSДокумент133 страницыAtty. Gacayan BILL OF RIGHTSAxel FontanillaОценок пока нет

- Clare Rewcastle Brown (Sarawak Report) Counterclaim To Hadi Awang's Suit - SummaryДокумент4 страницыClare Rewcastle Brown (Sarawak Report) Counterclaim To Hadi Awang's Suit - SummarySweetCharity77Оценок пока нет

- Jesse White, Eileen White and Nicole White v. Sharlene WatazychynДокумент64 страницыJesse White, Eileen White and Nicole White v. Sharlene WatazychynJesse WhiteОценок пока нет

- Yambot v. TuqueroДокумент2 страницыYambot v. TuqueroNat DuganОценок пока нет

- Employment LawДокумент28 страницEmployment LawAjmal HaziqОценок пока нет

- Palad vs. SolisДокумент20 страницPalad vs. SolisRap VillarinОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law 2 CasesДокумент11 страницCriminal Law 2 CasesPhoebe VillanuevaОценок пока нет

- Criminal Actions, EtalДокумент2 страницыCriminal Actions, EtalJudilyn RavilasОценок пока нет

- Malaysian Actor Sues Production Company for Assault, Defamation and Breach of ContractДокумент179 страницMalaysian Actor Sues Production Company for Assault, Defamation and Breach of ContractFaqihah FauziОценок пока нет

- AIA Code of Ethics and CommentsДокумент35 страницAIA Code of Ethics and CommentsObai NijimОценок пока нет

- Ticman Criminal LawДокумент216 страницTicman Criminal LawRegine GumbocОценок пока нет

- W. Reich'' Control Clima Via Cloudbuster - by James DeMeoДокумент16 страницW. Reich'' Control Clima Via Cloudbuster - by James DeMeoCarlos A. ArayaОценок пока нет

- Petitioner T40Документ30 страницPetitioner T40Haritima SinghОценок пока нет

- The Law of Tort, Professional Liability and Consumer ProtectionДокумент42 страницыThe Law of Tort, Professional Liability and Consumer ProtectionShirdah AgisteОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 180832 July 23, 2008 Jerome CASTRO, Petitioner, People of The Philippines, RespondentДокумент2 страницыG.R. No. 180832 July 23, 2008 Jerome CASTRO, Petitioner, People of The Philippines, RespondentTinОценок пока нет

- Ateneo Law School Outline on Philippine Corporation LawДокумент89 страницAteneo Law School Outline on Philippine Corporation LawMoira Sarmiento89% (9)

- Republic of The Philippines v. Salem Investment CorporationДокумент20 страницRepublic of The Philippines v. Salem Investment CorporationMaricar Corina CanayaОценок пока нет

- Torts - Meaning, Essentials, Personal CapacityДокумент116 страницTorts - Meaning, Essentials, Personal CapacityKiran AmateОценок пока нет

- Soriano V IacДокумент2 страницыSoriano V IacAlexir MendozaОценок пока нет

- Milton - Bateman ComplaintДокумент9 страницMilton - Bateman ComplaintCNBC.com100% (1)

- Criminal Procedure Reviewer Rule 110 112Документ26 страницCriminal Procedure Reviewer Rule 110 112Ken Tuazon100% (1)

- Electronic Media Law and RegulationДокумент537 страницElectronic Media Law and Regulationemilija_milicevicОценок пока нет