Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

6 - Sri Aurobindo's Perspective On The Future of Science

Загружено:

K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

6 - Sri Aurobindo's Perspective On The Future of Science

Загружено:

K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

73

SRI AUROBINDOS PERSPECTIVE ON THE

FUTURE OF SCIENTIFIC STUDY

CHANDRA PITCHAL

Science and scientific study are high points of the world-civilisation today. We all enjoy

the benefits of what the sciences have discovered and laid at our disposal as products or

conveniences of the modern world. There is a large consensus on what science is and

what scientific study implies in India and abroad. Generally, when we hear any reference

to Indian perspective on science, it is about a perspective from Indias ancient past, but in

this essay I explore more specifically the perspective on scientific study that Sri

Aurobindo envisages for India and the world in the future. This future perspective, of

course, looks to the ancient for its source and aims to synthesise within itself the present

as well.

Modern science originated in the western world, where there is a neat divorce

between philosophy, religion, and science in the search for truth. Each had its golden

days in the course of European history, but science has come out triumphant by asserting

itself over the other two. It claims greater rigour and certitude in its results, sticks to a

certain area of life where it can apply its vast generalisations without further

complications, and has defined its methods. We stay in the outer, surface life of body,

mind, and emotions, we stick to facts that are sensory and visible, and we limit our scope

to the tangible world that our intellectual mind and the man-made tools can quantify or

access.

The results are there for all to see. However, with time, the areas of application of

science have grown and from the domain of the physical sciences (physics, chemistry,

biology), it has encroached more and more on other areas of human interest where the

same methods are applied. The new areas have been more subjective and once again

science has had to divorce from a part of its quest and sub-divide into hard and soft

sciences, where the hard sciences are deemed capable of accessing the answer to a given

question, whilst the soft sciences can find only a relative answer. The latter have in turn

retaliated by producing extensive literature on the functioning of science, its

methodologies, its human organisations, and through different vantage points shown

how scientific knowledge is produced, and highlighted the grey areas of incertitude in

the quest.

February-April 2010

Vol. XI I & II NEW RACE

74

Philosophers like Popper have shown how there is dogma in science too. Where

there is dogma, there is the scent of religion and hence, for any theory to be truly

scientific, it has also to be refutable, and paradoxically to become less certain: debatable,

disputable and disprovable, just as it had to be verifiable. This brings to the fore another

divorce of science, a more subtle divorce, between the phenomena and the theories. Even

if a phenomenon seems to work always in the same manner, the intellectual theory that

explains why it is so can change with the advance of science. It is called progress! The

idea of progress is intrinsically linked to the idea of science as different from religion,

since religion demands faithfulness to teachings of the past.

In Conversations with Sri Aurobindo, (Pavitra, p. 145), Sri Aurobindo says, Again

scientific hypotheses have no character of truth. Very often it is possible to give two

different theories explaining the very same facts so they have equal value. In such a

case probabilities are more important than truth.

In fact ambiguities and dead ends seem to plague the sciences more and more,

where the impossibility to understand or explain has lead to a further divorce between

the sensible reality and the abstract models. Instead of explaining phenomena, science

has started substituting them with mathematical models that describe but dont explain

in any way. Hence each new discovery leads to a set of changes in the mathematical

model. The theory is ad hoc and on top of it, does not say what the phenomenon is, of

what it is made and why it is working. It only describes it. The only concrete reality is

that the physical phenomenon works.

There are times when even a mathematical model does not describe the physical

reality, then an unknown is invented or postulated (often in the form of a new particle, a

new force, or a new principle), an unknown which makes the reality as it is but about

which we cannot say anything since it is unknown. It cannot even be detected. Its

existence is only there to justify what cannot be explained by physics or by mathematics.

Dark matter is one such example but there are several others. So the once reliable hard

sciences are having a hard time answering fundamental questions of reality. They are not

alone.

The soft sciences too have similar problems. We find different frameworks of

study and analysis in each of them, and they too vary in time according to the theories in

vogue in the world at that point of time, or the personal taste of the scholar for one

particular mode of analysis. So we have structuralism, and deconstruction and

psychoanalysis, or just sets of concepts that act like the mathematical models and provide

a lens to categorise any phenomenon, or to string a collection of facts together. The fact

that they become obsolete and replaced with new models does not seem to disturb

anyone, since it reflects the progress of science.

What characterises this approach to science is the slow ascension towards less

tangible realities. We start with the physical domains, we shift to more psychological

February-April 2010

Vol. XI I & II NEW RACE

75

realities, and all through scientific study implies a hypothesis that is supported by

sources or instruments external to it. We then shift to the most subjective area of

interrogation, we are in the presence of a writer, an author, a philosopher, or an artist, his

analysis of the world, of society, of the human being and of self, is delivered as it is,

without justifications external to himself, that normally science would have demanded.

His word seems to be authoritative, and any of the sciences will use it as evidence to a

claim. A consensus seems to grow around his expertise, his authorship. The validity of

his claim is not always questioned even though it would be possible to do so. We have

moved from down to up, from the material world to areas intangible or unintelligible

sometimes, but there is here some searching for truth and saying something about it

which is being accepted. This is the best that the present fragmented notion of reality can

produce. We will now see how, in contrast, the Indian perspective evolves from the top

downwards.

Photo credit: groups.google.com/group/holy_trinity/web/some-of-the-great-men-of-ancient-india

The ancient Indian perspective on science did not have to struggle with these

divisions and fragmentations. Philosophy, spirituality, religion and science were not at

war and only confirmed each others findings. The outlook in the search for truth went

top down and not the other way round like in modern science. The discovery of the

Spirit came first and led to the discovery of Dharma, the inner law of all things, and that

led to Shastra, the science that was formulated from the laws. We see here a very unitary

knowledge where the same principles, the same methods are applied to a scope

extending from God to matter and often down to the inconscient reality. The same

principle explains different levels of existence down to the level of physical science. The

methods and experimentation have the same rigour at all levels of reality, except that the

February-April 2010

Vol. XI I & II NEW RACE

76

more subtle realities require a more subtle experimentation and the use of a subtler

instrument of the mind, called intuition. It seeks the truth and nothing less and that too

with certitude. And whatever theory has been formulated about a reality has to apply to

all levels of that reality from the physical to the supra-physical layers. Its vast

applicability and its being in harmony with all else would prove its veracity.

The Vedic period mentioned three layers of interpretation or analysis where each

layer actually involves many more levels of interpretation in our contemporary terms.

This triple analysis was primarily for the interpretation of Vedic texts, but actually

applies to all realities. First was adhyatmika, which might cover for us the spiritual,

philosophical, religious, yogic and psychological seed motives of the reality. This reality

contains the non-material powers and is greater than them; it is the Self or Spirit, tman,

and everything that has to do with this highest existence in us is called the spiritual,

adhytma (Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, vol. 18, p. 18). Next came adhidaivika that probably

covers the levels of occultism, occult laws, the working of natures forces, and some types

of yogic experience, cosmogony, cosmology, some areas of Indian psychology and the

science of rituals. The material world is moved by non-material powers manifesting

through the Mind-Force and Life-Force that work upon Matter, and these are called Gods

or Devas; everything that has to do with the working of the non-material in us is called

adhidaiva, that which pertains to the Gods<the adhidaiva is the subtle in us; it is that

which is represented by Mind and Life as opposed to gross Matter; for in Mind and Life

we have the characteristic action of the Gods (Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, vol. 18, p. 18). At

the third level of analysis, the adhibhautika level, we are dealing with the material and

physical consciousness and on the area of external Nature, and all the known modern

sciences, hard or soft would figure at this level. Our material existence is formed from

the five elemental states of Matter, the ethereal, aerial, fiery, liquid and solid; everything

that has to do with our material existence is called the elemental, adhibhta (Sri

Aurobindo, CWSA, vol. 18, p. 18).

We note here how the same reality is studied from many perspectives and from a

multitude of levels. Sri Aurobindo would call this the synthetic turn of the Indian mind,

its cosmic viewpoint on reality, which is actually a very exact description of the operation

of Indian science. From our modern viewpoint, we can marvel at the inter-disciplinary,

trans-disciplinary and cross-cultural nature of the approach. This synthetic view of

reality can be best compared to Indian painting, where the same panel will include many

different points of perspective that harmoniously and simultaneously co-exist with the

narrative in time that the painting is depicting. This might lead us to distinguish the

levels and the domains. There can be many levels in the same domain, many

perspectives in the same theme, and that theme or domain will also be a moving reality

in time, changing, unfolding. The complexity of reality is apprehended in a

comprehensive manner. Sri Aurobindo has also used this approach, hence we find him

February-April 2010

Vol. XI I & II NEW RACE

77

giving us the essence of a phenomenon, its paradoxes that arise from its different levels,

its difficulties and dangers with all its attractions for yesterday, today and for tomorrow.

This immediately unveils the phenomenon as profound in the most perfect manner,

rationality contributing to the richness of understanding, rather than understanding

through impoverishment of the phenomenon.

We also observe here a certain correlation between the triptych of Spirit, Dharma

and Shastra and that of the three modes of analysis, namely adhytmika, adhidaivika and

adhibhautika. In its unfolding, a phenomenon is like an organism with a soul, mind and

body: analysed as a seed-idea, it is an unfolding process or expression and external

manifestation. A close scrutiny of and deeper study of these correlations on three

different levels would certainly yield much for the future of scientific study in the light of

Sri Aurobindo. It points to the unitary nature of truth and knowledge, and how what

applies to scriptural interpretation can also be a means of seeing history, evolution, the

evaluation of a civilisation, and many other areas of scientific interest.

So what are the chances of our understanding a theory that goes beyond the

mind and delves into realities that are outside the scope of modern science? Can we go

higher, deeper, and larger? To this Sri Aurobindo replies:

The knowledge that science possesses is one thing and not a large one the

scientific attitude is another. The capacities of observation, of study, of reserving

ones judgement and building a conclusion only after all available data have been

gathered, of keeping the mind open to any suggestion, any clue about a higher

truth, this attitude is indispensable to the occultist also... But the criteria of the

physical plane are not valid on the vital plane. The vital plane is the world of

spell and deceit and power. The methods of modern science are good so far as the

physical plane is concerned; they are not acceptable for the higher ones. For these

planes, the ancient method of developing the higher knowledge under the

guidance of the Guru has its raison dtre (Pavitra, p. 135).

Through this we see that just as we learn to go into a fresh scientific enquiry under the

guidance of the person who oversees a doctoral thesis, we learn through a Guru on how

to access higher planes of knowledge and conduct an enquiry into them. The modes of

perception and discrimination will vary as we rise to higher levels. This opens up two

questions for us: (1) Since, according to Sri Aurobindo, science is going to study the

occult phenomena and the occult worlds in the future, why did the Indian yogis not

complete the occult knowledge with the physical knowledge in the first place? (2) How

can we, mental creatures with no intuition and no higher knowledge, throw ourselves

into scientific discovery in the Indian perspective?

February-April 2010

Vol. XI I & II NEW RACE

78

One of Sri Aurobindos answers to the first question is: The Hindu Yogis who

realised these truths did not elaborate on them and turn them into scientific knowledge.

Other fields of action and knowledge having been opened before them, they neglected

what for them was the most exterior aspect of the manifestation. There is a difference

between the scientific mind and the cast of mind of an occultist. There is little doubt that

someone who could unite these two groups of faculties would lead science towards great

progress (Pavitra, p. 141).

The yogis were satisfied with the higher vistas of the spiritual and the occult

knowledge and did not bother with the exteriority of physical knowledge. However, to

our modern minds, seeking the truth from down to up, the occult is the next plane that

beckons: bridging the physical and the occult is an imperative necessity. A scientist who

harnessed that capacity would take science very far.

But this is not the only reason why the Indian yogis did not arrive at a still larger

synthesis; there is a second reason for it. In The Renaissance in India, Sri Aurobindo throws

further light on this aspect of the future of science. Here he is using the term psychic

science for the occult sciences:

Indian metaphysics did not attempt, as modern philosophy has attempted

without success, to read the truth of existence principally by the light of the truths

of physical Nature. This ancient wisdom founded itself rather upon an inner

experimental psychology and a profound psychic science, Indias special

strength, but study of mind too and of our inner forces is surely study of nature,

in which her success was greater than in physical knowledge. This she could

not but do, since it was the spiritual truth of existence for which she was seeking;

nor is any great philosophy possible except on this basis. It is true also that the

harmony she established in her culture between philosophical truth and truth of

psychology and religion was not extended in the same degree to the truth of

physical Nature; physical Science had not then arrived at the great universal

generalisations which would have made and are now making that synthesis

entirely possible. Nevertheless from the beginning, from as early as the Vedas,

the Indian mind had recognised that the same general laws and powers hold in

the spiritual, the psychological and the physical existence (Sri Aurobindo, CWSA,

vol. 20, p. 124).

This extract beautifully summarises the cosmic scope of Indian science, what we

need to do and where we need to go, as also the three levels adhytmika (spiritual),

adhidaivika (psychological), and adhibhautika (physical existence). We cannot continue

working from down to up if we want to have any certitude in our theories. The

philosophy, the general laws and powers function from above downwards, and are the

February-April 2010

Vol. XI I & II NEW RACE

79

same on every level. Thus since the yogis have already developed the synthetic

knowledge in the Vedanta for us, we can proceed from where they left. Also since

physical Science has made a progress that did not exist at that time, we can push

upwards from there too and come to a great synthesis of the future.

This extract also replies to the second question asked: even though we do not

possess the higher capacities that would be necessary, we can pick up the spirit and the

laws laid down by the yogis and elaborate a synthesis that becomes possible at this

juncture in time. For this we first have the large synthesis of philosophical and yogic

knowledge of the past that Sri Aurobindo has provided us, with an especial push

towards the future, giving us all the needed clues to move forward. If we can translate

these laws into language and structure that can accommodate the understanding of the

physical sciences, then we come to a great future synthesis. Secondly, Sri Aurobindo

himself has led the way by giving us concrete examples.

For example, in The Renaissance in India, he lays down the principles of the study

and evaluation of culture and civilisation and goes on to brilliantly apply those principles

to provide us with a deep all-round study of the subject. He is treating civilisation and

culture like an organism, just as elsewhere he has talked of the soul of a nation and

treated the nation as a person. This is in line with the unitary nature of knowledge;

similar laws apply to the singular human and the collective human, and as in other

studies to collectives of humans trying to organise themselves around a principle of

harmony. In another example, at the end of his book Hymns to the Mystic Fire, in the

supplement called The first Rik of the Rig-Veda (SABCL, Vol. 11, pp. 439-458), Sri

Aurobindo has given us a detailed study of just this one line: Agni I adore, who stands

before the Lord, the god who sees Truth, the warrior, strong disposer of delight. In his

word-by-word analysis of the line, he seamlessly moves through all the levels of science

possible, ancient sciences, supra-physical sciences, modern and physical sciences,

without the slightest irrationality, and with the greatest ease. It constitutes for me a great

model of what a scientific analysis of the future could be, and how it could integrate and

synthesise all the levels of reality from the highest to the lowest. We find here points of

view from varied sciences: material perception, subtle physical perception, the essential

truth, the nature of the Supreme, Vedic psychology, mythological study, historical study,

physical science, physics, biology, the point of view of divine consciousness, the point of

view of human consciousness, the perception from the yogic consciousness, modern

psychology, epistemology, philology, metaphysics, grammatical perspectives, occult

sciences, textual analysis, symbolism, etymology, social development, and very many

more that I am yet to understand. It is a masterpiece and its close study would reveal

much to us.

On a concluding note we could say that the objective of any science past or

present is the search for truth. The scope of the scientific endeavour defines its methods.

February-April 2010

Vol. XI I & II NEW RACE

80

If Indian scientific pursuit has had a greater scope and more capacities and methods

involved, it has also had the right approach to truth by reading the supreme first and

foremost, and coming slowly down to the level of life in the world with the aid of the

same first principles, as all levels will find their raison dtre in their relation to the Origin.

In this it can provide a valuable input to modern science, by giving it theories in truth

and a reliable scheme of values. However, Shastra is not the last word in the realm of

science and an even greater synthesis is in the offing which will require a bridging of the

gap between modern science and the verities of Shastra and of Vedanta through the

systematic bridging of occult and physical sciences. Possibly, a greater knowledge of the

panchabhtas (the five elements of the adhibhta), foremost among them being ether,

would provide the link between physical science and other higher forms of knowledge,

permitting a smooth passage from one level to the other. This would require us to grow

beyond our present mental capacity and develop higher faculties of knowledge, a

widening of our efforts, and a greater strength of formulation.

(In writing this article I have benefited from remarks and suggestions made by Dr. Beloo

Mehra, Dr. Olivier Pironneau and Sraddhalu Ranade).

References

Pavitra, Conversations with Sri Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, Pondicherry,

2007.

Sri Aurobindo, Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, vol. 18, Kena and Other Upanishads, Sri

Aurobindo Ashram Trust, Pondicherry, 2001.

Sri Aurobindo, Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, vol. 20, The Renaissance in India, Sri

Aurobindo Ashram Trust, Pondicherry, 1997.

Sri Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo Birth Centenary Library, vol. 11, Hymns to the Mystic Fire,

Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, Pondicherry, 1971.

February-April 2010

Vol. XI I & II NEW RACE

Вам также может понравиться

- Volume 10. Immortality is accessible to everyone. «Fundamental Principles of Immortality»От EverandVolume 10. Immortality is accessible to everyone. «Fundamental Principles of Immortality»Оценок пока нет

- Lesson 1Документ9 страницLesson 1Airabel GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Sankhya and Science: Applications of Vedic Philosophy to Modern ScienceОт EverandSankhya and Science: Applications of Vedic Philosophy to Modern ScienceРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (2)

- Consciousness and Cosmos: Proposal for a New Paradigm Based on Physics and InrospectionОт EverandConsciousness and Cosmos: Proposal for a New Paradigm Based on Physics and InrospectionОценок пока нет

- Philosophy Is A Study That Seeks To Understand The Mysteries of Existence and RealityДокумент11 страницPhilosophy Is A Study That Seeks To Understand The Mysteries of Existence and RealityMArk KUlitОценок пока нет

- Science and Supernatural IsmДокумент15 страницScience and Supernatural IsmV.K. MaheshwariОценок пока нет

- Realism Vs InstrumentalismДокумент4 страницыRealism Vs InstrumentalismLaki10071987Оценок пока нет

- Cosmology and Consciousness: A Comparative Study of Hindu Metaphysics and PhysicsОт EverandCosmology and Consciousness: A Comparative Study of Hindu Metaphysics and PhysicsОценок пока нет

- Contemplative Science: Where Buddhism and Neuroscience ConvergeОт EverandContemplative Science: Where Buddhism and Neuroscience ConvergeОценок пока нет

- Wisdom and Artificial IntelligenceДокумент7 страницWisdom and Artificial IntelligenceShmaiaОценок пока нет

- Quantum Physics and Ultimate Reality: Mystical Writings of Great PhysicistsОт EverandQuantum Physics and Ultimate Reality: Mystical Writings of Great PhysicistsОценок пока нет

- What's A Theory?Документ21 страницаWhat's A Theory?mira01Оценок пока нет

- Destination Of The Species: The Riddle of Human ExistenceОт EverandDestination Of The Species: The Riddle of Human ExistenceРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- Lecture 1 - Environmental Philosophy: An Introduction: Spring 2022 - Lecture-1: Notes - p.1Документ11 страницLecture 1 - Environmental Philosophy: An Introduction: Spring 2022 - Lecture-1: Notes - p.1Shubham SharmaОценок пока нет

- Science and SpiritualityДокумент3 страницыScience and SpiritualitySunitha KrishnanОценок пока нет

- Volume 11. Immortality is accessible to everyone. «Energy and biological mechanisms of refocusings of Self-Consciousness»От EverandVolume 11. Immortality is accessible to everyone. «Energy and biological mechanisms of refocusings of Self-Consciousness»Оценок пока нет

- Short Introduction To Vedanta According To Gaudiya VaishnavasДокумент3 страницыShort Introduction To Vedanta According To Gaudiya VaishnavastazinabhishekОценок пока нет

- Introduction To The Philosophy of Man What Is Philosophy?Документ2 страницыIntroduction To The Philosophy of Man What Is Philosophy?Arylle ArpiaОценок пока нет

- Science and MysticismДокумент3 страницыScience and MysticismkarnsatyarthiОценок пока нет

- The Self-Actualizing Cosmos: The Akasha Revolution in Science and Human ConsciousnessОт EverandThe Self-Actualizing Cosmos: The Akasha Revolution in Science and Human ConsciousnessОценок пока нет

- History of scientific psychology: From the birth of psychology to neuropsychology and the most current fields of applicationОт EverandHistory of scientific psychology: From the birth of psychology to neuropsychology and the most current fields of applicationОценок пока нет

- Arthur M Young The Theory of ProcessДокумент16 страницArthur M Young The Theory of ProcessukxgerardОценок пока нет

- NotesДокумент16 страницNotesRakesh KumarОценок пока нет

- Rpe 01: Philosophy and Ethics ObjectivesДокумент167 страницRpe 01: Philosophy and Ethics ObjectivesVasudha SharmaОценок пока нет

- Lecture 1 - Environmental Philosophy: An Introduction: Autumn 2021 - Lecture-1: Notes - p.1Документ11 страницLecture 1 - Environmental Philosophy: An Introduction: Autumn 2021 - Lecture-1: Notes - p.1Manav VoraОценок пока нет

- The Question of Method For Existential Psychology: A Response To Paul T. P. WongДокумент4 страницыThe Question of Method For Existential Psychology: A Response To Paul T. P. WongInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesОценок пока нет

- The Importance of Philosophy in Human LifeДокумент13 страницThe Importance of Philosophy in Human LifeRamona Baculinao100% (1)

- Logical Faith: Introducing a Scientific View <Br>Of Spirituality and ReligionОт EverandLogical Faith: Introducing a Scientific View <Br>Of Spirituality and ReligionОценок пока нет

- Articulo Body and SocialДокумент8 страницArticulo Body and SocialAngiee Ramirez MuñozОценок пока нет

- Philosophical Foundations: Ontology, Epistemology and Research ParadigmsДокумент19 страницPhilosophical Foundations: Ontology, Epistemology and Research ParadigmsIshmam Mohammad AdnanОценок пока нет

- MetaphysicsДокумент20 страницMetaphysicscrisjava100% (1)

- Beyond the Observable: A Philosophical Take on Scientific UnderstandingОт EverandBeyond the Observable: A Philosophical Take on Scientific UnderstandingОценок пока нет

- Lecture Notes On PHL 205 Philosophy of Science.Документ116 страницLecture Notes On PHL 205 Philosophy of Science.alloyihuah75% (8)

- The Challenge of Fate - Thorwald DethlefsenДокумент124 страницыThe Challenge of Fate - Thorwald DethlefsenAndreas Papazachariou91% (22)

- Philosophy CH 1Документ18 страницPhilosophy CH 1Ali YilmazОценок пока нет

- Conceiving the Inconceivable Part 1: A Scientific Commentary on Vedānta Sūtras: Six Systems of Vedic Philosophy, #1От EverandConceiving the Inconceivable Part 1: A Scientific Commentary on Vedānta Sūtras: Six Systems of Vedic Philosophy, #1Оценок пока нет

- What Philosophy IsДокумент7 страницWhat Philosophy IsApril Janshen MatoОценок пока нет

- Discuss The Nature of PhilosophyДокумент3 страницыDiscuss The Nature of PhilosophyUrbana RaquibОценок пока нет

- Tautological Oxymorons: Deconstructing Scientific Materialism:An Ontotheological ApproachОт EverandTautological Oxymorons: Deconstructing Scientific Materialism:An Ontotheological ApproachОценок пока нет

- Edward-Taking The Concepts of Others Seriously-2016Документ11 страницEdward-Taking The Concepts of Others Seriously-2016JesúsОценок пока нет

- Religion and Science as Forms of Life: Anthropological Insights into Reason and UnreasonОт EverandReligion and Science as Forms of Life: Anthropological Insights into Reason and UnreasonCarles SalazarОценок пока нет

- Substance and ShadowДокумент111 страницSubstance and Shadowgndasa108Оценок пока нет

- Taxonomy For The Technology DomainДокумент2 страницыTaxonomy For The Technology DomainK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОценок пока нет

- Andrew Jotischky-A Hermit's Cookbook - Monks, Food and Fasting in The Middle Ages-Continuum (2011) PDFДокумент224 страницыAndrew Jotischky-A Hermit's Cookbook - Monks, Food and Fasting in The Middle Ages-Continuum (2011) PDFK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (2)

- Reconstructing The Tree of LifeДокумент1 страницаReconstructing The Tree of LifeK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- Taxonomy Matching Using Background KnowledgeДокумент3 страницыTaxonomy Matching Using Background KnowledgeK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- (Systematics Association Special Volumes) Trevor R. Hodkinson, John A.N. Parnell-Reconstructing The Tree of Life - Taxonomy and Systematics of Species Rich Taxa-CRC Press (2006) PDFДокумент374 страницы(Systematics Association Special Volumes) Trevor R. Hodkinson, John A.N. Parnell-Reconstructing The Tree of Life - Taxonomy and Systematics of Species Rich Taxa-CRC Press (2006) PDFK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (2)

- Primitive Classification Émile Durkheim and Marcel MaussДокумент6 страницPrimitive Classification Émile Durkheim and Marcel MaussK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОценок пока нет

- Subrahmanya Sastri An Alphabetical Index of Sanskrit Manuscripts in The GOML Madras v2 Biswas0633 1940Документ357 страницSubrahmanya Sastri An Alphabetical Index of Sanskrit Manuscripts in The GOML Madras v2 Biswas0633 1940K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОценок пока нет

- Anxieties of Attachment, The Dynamics of Courtship in Medieval IndiaДокумент38 страницAnxieties of Attachment, The Dynamics of Courtship in Medieval IndiaK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОценок пока нет

- Yajnavalkya Smrit DharamshastraДокумент476 страницYajnavalkya Smrit Dharamshastrakhalil_rehman_26100% (2)

- Lily Abegg, The Mind of East AsiaДокумент365 страницLily Abegg, The Mind of East AsiaK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОценок пока нет

- What The Cārvākas Originally Meant, More On The Commentators On The CārvākasūtraДокумент15 страницWhat The Cārvākas Originally Meant, More On The Commentators On The CārvākasūtraK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- Brahma Siddhi - By.mandana - Misra SanskritДокумент643 страницыBrahma Siddhi - By.mandana - Misra SanskritGirirajPurohitОценок пока нет

- Religion in Iran, The Parthian and Sasanian PeriodsДокумент33 страницыReligion in Iran, The Parthian and Sasanian PeriodsK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОценок пока нет

- The Rasa Theory and The DarśanasДокумент21 страницаThe Rasa Theory and The DarśanasK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (2)

- A Glossary of Indian Figures of SpeechДокумент128 страницA Glossary of Indian Figures of SpeechK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- Why Yoga, A Cultural History of YogaДокумент572 страницыWhy Yoga, A Cultural History of YogaK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (1)

- Dhvanyaloka 2Документ23 страницыDhvanyaloka 2K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОценок пока нет

- Dhvanyaloka 1Документ13 страницDhvanyaloka 1K.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОценок пока нет

- Tarkabhasa of Sri Kesava MisraДокумент352 страницыTarkabhasa of Sri Kesava MisraK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiОценок пока нет

- Clinical Nursing SkillsДокумент2 страницыClinical Nursing SkillsJoeОценок пока нет

- Reimprinting: ©michael Carroll NLP AcademyДокумент7 страницReimprinting: ©michael Carroll NLP AcademyJonathanОценок пока нет

- Modern Prometheus Editing The HumanДокумент399 страницModern Prometheus Editing The HumanHARTK 70Оценок пока нет

- EC SF Presentation 02Документ10 страницEC SF Presentation 02Ahmed NafeaОценок пока нет

- Armor MagazineДокумент56 страницArmor Magazine"Rufus"100% (2)

- Procedures: Step 1 Freeze or Restrain The Suspect/sДокумент5 страницProcedures: Step 1 Freeze or Restrain The Suspect/sRgenieDictadoОценок пока нет

- Ron Clark ReflectionДокумент3 страницыRon Clark Reflectionapi-376753605Оценок пока нет

- Oral Abstract PresentationДокумент16 страницOral Abstract Presentationapi-537063152Оценок пока нет

- Conducting A SeminarДокумент17 страницConducting A SeminarSubhash DhungelОценок пока нет

- Chapter 23 AP World History NotesДокумент6 страницChapter 23 AP World History NotesWesley KoerberОценок пока нет

- SD OverviewДокумент85 страницSD OverviewSamatha GantaОценок пока нет

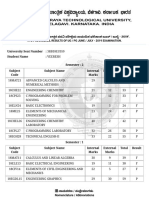

- VTU Result PDFДокумент2 страницыVTU Result PDFVaibhavОценок пока нет

- Heart Rate Variability - Wikipedia PDFДокумент30 страницHeart Rate Variability - Wikipedia PDFLevon HovhannisyanОценок пока нет

- CH 13 ArqДокумент6 страницCH 13 Arqneha.senthilaОценок пока нет

- Jataka Tales - The Crane and The CrabДокумент5 страницJataka Tales - The Crane and The Crabshahrajan2k1Оценок пока нет

- SKZ TrackДокумент6 страницSKZ TrackOliviaОценок пока нет

- Reaction PaperДокумент4 страницыReaction PaperCeñidoza Ian AlbertОценок пока нет

- Voucher-Zona Wifi-@@2000 - 3jam-Up-764-04.24.24Документ10 страницVoucher-Zona Wifi-@@2000 - 3jam-Up-764-04.24.24AminudinОценок пока нет

- 2009FallCatalog PDFДокумент57 страниц2009FallCatalog PDFMarta LugarovОценок пока нет

- Si493b 1Документ3 страницыSi493b 1Sunil KhadkaОценок пока нет

- FBFBFДокумент13 страницFBFBFBianne Teresa BautistaОценок пока нет

- G12 PR1 AsДокумент34 страницыG12 PR1 Asjaina rose yambao-panerОценок пока нет

- Anecdotal Records For Piano Methods and Piano BooksДокумент5 страницAnecdotal Records For Piano Methods and Piano BooksCes Disini-PitogoОценок пока нет

- Top Websites Ranking - Most Visited Websites in May 2023 - SimilarwebДокумент3 страницыTop Websites Ranking - Most Visited Websites in May 2023 - SimilarwebmullahОценок пока нет

- 3.1 Learning To Be A Better StudentДокумент27 страниц3.1 Learning To Be A Better StudentApufwplggl JomlbjhfОценок пока нет

- Dispeller of Obstacles PDFДокумент276 страницDispeller of Obstacles PDFLie Christin Wijaya100% (4)

- Arthur Brennan Malloy v. Kenneth N. Peters, 11th Cir. (2015)Документ6 страницArthur Brennan Malloy v. Kenneth N. Peters, 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Chemistry Chapter SummariesДокумент23 страницыChemistry Chapter SummariesHayley AndersonОценок пока нет

- 4.1 Genetic Counselling 222Документ12 страниц4.1 Genetic Counselling 222Sahar JoshОценок пока нет

- BS Assignment Brief - Strategic Planning AssignmentДокумент8 страницBS Assignment Brief - Strategic Planning AssignmentParker Writing ServicesОценок пока нет