Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Impacts of Organizational Learning Culture

Загружено:

Atiq Ur RehmanАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Impacts of Organizational Learning Culture

Загружено:

Atiq Ur RehmanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Intrinsic Motivation 1

Running head: Intrinsic Motivation

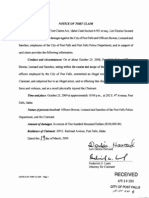

THE IMPACTS OF ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING CULTURE AND PROACTIVE

PERSONALITY ON ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND INTRINSIC

MOTIVATION: THE MEDIATING ROLE OF PERCEIVED JOB COMPLEXITY

BAEK-KYOO (BRIAN) JOO

Winona State University

P.O. Box 5838

Winona, MN 55987

Tel: (507) 457-5191

Email: bjoo@winona.edu

TAEJO LIM

Samsung HRD Center

Yongin, Gyunggi-do, Korea

Email: levulim.lim@samsung.com

Author Note: This paper is submitted for a conference proceeding of 2008 Midwest Academy of

Management Conference. The correspondence should be directed to the first author. This

manuscript has not been presented or published elsewhere at the time it is submitted.

Intrinsic Motivation 2

THE IMPACTS OF ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING CULTURE AND PROACTIVE

PERSONALITY ON ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AND INTRINSIC

MOTIVATION: THE MEDIATING ROLE OF PERCEIVED JOB COMPLEXITY

This paper investigates the impact of personal characteristics (proactive personality)

and contextual characteristics (organizational learning culture and job complexity) on

employees intrinsic motivation and organizational commitment. The results suggest

that employees exhibited the highest organizational commitment, when the

organization had a higher learning culture. Employees were more intrinsically

motivated, when they showed higher proactive personality. The perception of their

job complexity partially mediated the relationships between the antecedents (i.e.,

organizational learning culture and proactive personality) and the consequences (i.e.,

organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation).

Key words: Organizational Commitment, Organizational Learning, Leader-Member Exchange

The impact of organizational commitment on individual performance and organizational

effectiveness has prompted much interest among researchers (Allen & Meyer, 1996; Beck &

Wilson, 2000; Mowday, 1998). Organizational commitment refers to an individuals feelings

about the organization as a whole. It is the psychological bond that an employee has with an

organization and has been found to be related to goal and value congruence, behavioral

investments in the organization, and likelihood to stay with the organization (Mowday, Steers, &

Porter, 1982). It has become more important than ever in understanding employee work-related

behavior because it is identified as more stable and less subject to daily fluctuations than job

satisfaction (Angle & Perry, 1983; Mowday, Steers, & Porter, 1982). While the antecedents of

organizational commitment include organizational characteristics, personal characteristics,

group/leader relations, and job characteristics, the consequences of organizational commitment

are the job performance variables including intention to leave, turnover, and output measure

(Mathieu & Zajac, 1990).

People are more productive and creative, when they are motivated primarily by the passion,

interest, enjoyment, satisfaction, and challenge of the work itselfnot by external pressures or

rewards (Amabile, 1996; Amabile & Kramer, 2007). A necessary component of intrinsic

motivation is the individuals orientation or level of enthusiasm for the activity (Amabile, 1988).

While motivational orientation may be partially shaped by the environment (i.e., organizational,

social, job characteristics) (Amabile, 1983), there is also evidence suggesting a stable, trait-like

nature (e.g., Amabile, Hill, Hennessey, & Tighe, 1994). Thus, intrinsic motivation encompasses

both contextual and personal characteristics. Because intrinsic motivation affects an employees

decision to initiate and sustain creative effort over time (Amabile, 1988), intrinsic motivation has

been cited as one of the most prominent personal qualities for the enhancement of creativity

(Amabile, 1983, 1988, 1996).

Organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation are important constructs in human

resources (HR) and organization behavior (OB) field. Both constructs share the personal

characteristics and contextual characteristics for their antecedents. Moreover, they are two of the

most frequently used variables for satisfaction, performance, change, and innovation and

creativity. Although the consequences of organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation are

Intrinsic Motivation 3

not in the scope of this study, they ultimately influence on employee creativity, innovation, and

organizational performance and employee job/career satisfaction and turnover. While the extent

of research on intrinsic motivation and organizational commitment has increased during the past

two decades, little research has been conducted, focusing on the two topics simultaneously.

The purpose of this research is to investigate the impact of personal characteristics (i.e.,

proactive personality) and contextual characteristics (i.e., organizational learning culture and job

complexity) on intrinsic motivation and organizational commitment of employees. The

theoretical contributions of this study lie in its integrative approach encompassing both personal

and contextual factors. Another contribution is that it links organizational commitment research

with motivation research. This article is divided into four parts. The first part provides a

theoretical framework and hypotheses. Then, research methods including data collection and

measures are described. The next part summarizes the research findings, based on a confirmatory

factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation model (SEM) analysis. Finally, the implications,

limitations, and future research areas will be discussed.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

As a result of a comprehensive literature review, a set of constructs was selected: proactive

personality for personal characteristics and organizational learning culture and job complexity

for contextual characteristics. These constructs are considered necessary for influencing intrinsic

motivation and organizational commitment. The hypothesized model for this study is illustrated

in Figure 1.

--------------------------------------------Insert Figure 1 about here

--------------------------------------------Organizational Learning Culture

At the organizational level, organizational learning culture is one of the key contextual

components to enhance organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation. By definition, it

refers to an organization skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and at

modifying its behavior to reflect new knowledge and insights (Garvin, 1993: 80). Watkins and

Marsicks (1997) framework for the learning organization served as another theoretical base for

this study. They identified seven action imperatives for a learning organization: (1) create

continuous learning opportunities; (2) promote inquiry and dialogue; (3) encourage collaboration

and team learning; (4) establish systems to capture and share learning; (5) empower people to

have a collective vision; (6) connect the organization to the environment, and (7) use leaders who

model and support learning at the individual, team, and organization levels. Thus, learning

organization involves an environment in which organizational learning is structured so that

teamwork, collaboration, creativity, and knowledge processes have a collective meaning and

value (Confessore & Kops, 1998).

Intrinsic Motivation 4

Proactive Personality

People are not always passive recipients of environmental constraints on their behavior;

rather, they can intentionally and directly change their current circumstances (Crant, 2000).

Bateman and Crant (1993) introduced proactive disposition as a construct that identifies

differences among people to the extent that they take action to influence their environments.

Proactive people are likely to be those who define their role more flexibly, with ownership of

longer term goals beyond their job (Parker et al., 2006). Proactive personality is defined as a

belief in ones ability to overcome constraints by situational forces and the ability to affect

changes in the environment (Bateman & Crant, 1993). Thus, proactive personality is a complex,

multiple-caused construct that has important personal and organizational consequences (Crant,

2000).

More specifically, Crant (2000: 436) described proactive behavior as taking initiative in

improving current circumstances or creating new one; it involves challenging the status quo

rather than passively adapting to present conditions. By definition, employees with a proactive

personality are predisposed to enact their environments. Proactive individuals look for

opportunities and act on them, show initiative, take action, and are persistent in successfully

implementing change (Bateman & Crant, 1993; Crant, 2000). Therefore, proactive behavior is

more crucial than ever because of the changing nature of work (Parker, 1998).

Perceived Job Complexity

Job design has long been considered to be an important contributor to employees

individual motivation, attitudes, and creative performance at work (Amabile, 1988; Hackman &

Oldham, 1980; Kanter, 1988; Shalley et al., 2004; West & Farr, 1989). The job characteristics

model consists of five factors: variety, identity, significance, autonomy, and feedback (Hackman

& Oldham, 1980; Oldham & Cummings, 1996). As Drucker (1988) put it, organizations are

shifting to the information-based organization, or self-governing units of knowledge specialists.

Complex jobs demand creative outcomes by encouraging employees to focus simultaneously on

multiple dimensions of their work, whereas highly simple or routine jobs may inhibit such a

focus (Oldham & Cummings, 1996). When jobs are complex and challenging, individuals are

likely to be excited about their work activities and interested in completing these activities in the

absence of external controls or constraints (Hackman & Oldham, 1980; Oldham & Cummings,

1996; Shalley & Gibson, 2004).

Organizational learning culture Perceived job complexity. Job design will vary

depending on organizational environment, business domain or industry, and job function. In this

increasingly competitive environment in which frequent changes in technologies, markets,

government regulations and customers give rise to turbulence and unpredictability (Unsworth &

Parker, 2003, p. 175), organizational learning culture can significantly influence core job

characteristics in many ways. As Drucker (1988) put it, organizations are shifting to informationbased organizations, or self-governing units of knowledge specialists. Jobs not only in service

and knowledge work, but also in manufacturing are becoming more knowledge-oriented,

highlighting the importance of cognitive characteristics of work (Parker, Wall, & Cordery,

2001). By definition, knowledge work is unpredictable, multidisciplinary, and non-repetitive

tasks with evolving, long-term goals which, due to their inherent ambiguity and complexity,

Intrinsic Motivation 5

require collaborative effort in order to take advantage of multiple viewpoints (Janz, Colquitt, &

Noe, 1997, pp. 882-883).

Enriched forms of job design are most appropriate where uncertainty is high (Parker et al.,

2001), because autonomy has been identified to be salient for knowledge workers. It is likely that

an increasingly uncertain environment requires an organizational learning culture and that

knowledge workers prefer complex jobs (i.e., broadly defined jobs) to simple and routine work

(i.e., narrowly defined jobs) (Parker et al., 2001). In jobs that require high levels of knowledge

and creativity, job occupants work attitudes (i.e., the perception of job complexity) may vary

directly with the level of organizational learning culture. That is, attitudes should be more

favorable when environmental characteristics such as organizational learning culture

complement the knowledge and creativity requirements of the work (Marsick & Watkins, 2003;

Shalley, Gibson, & Blum, 2000).

Hypothesis 1: Organizational learning culture will be positively related to perceived job

complexity.

Proactive personality Perceived job complexity. Research has shown that positively

disposed individuals rate characteristics of the task or the job as more enriched than do less

positively disposed individuals (Judge, Bono, & Locke, 2000). Researchers have also argued that

narrow role orientations can impair performance (Karasek & Theorell, 1990; Parker et al., 1997).

For example, Klein (1976) found that Tayloristic job design can result in people having narrower

role orientations in which they are not interested in only their immediate job, which ultimately

stifles innovation (Parker et al., 2006). When employees are higher in proactive personality, they

were likely to perceive higher job complexity. That is, proactive people tend to rate job

characteristics as more enriched than do less positively disposed individuals (Brief, Butcher, &

Roberson, 1995; James & Jones, 1980; Judge et al., 1998; Judge et al., 2000; Kraiger, Billings, &

Isen, 1989; Necowitz & Roznowski, 1994; Parker et al., 2006).

Hypothesis 2: Proactive personality will be positively related to perceived job

characteristics.

Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment refers to an individuals feelings about the organization as a

whole. It is the psychological bond that an employee has with an organization and has been

found to be related to goal and value congruence, behavioral investments in the organization, and

likelihood to stay with the organization (Mowday, Steers, & Porter, 1982). Organizational

commitment is conceptualized as an affective response that results from an evaluation of the

work situation that links the individual to the organization. As Mowday et al. (1982) stated,

organizational commitment is the strength of an individuals identification with and

involvement in an organization (p. 27). It is the process by which the goals of the organization

and those of the individual become increasingly integrated or congruent (Hall, Schneider, &

Nygren, 1970).

Meyer and Allen (1966) have termed the three components as affective commitment,

continuance commitment, and normative commitment. Mowday et al. (1982) also identified

three characteristics of organizational commitment: (a) a strong belief in and acceptance of the

organizations goals and values; (b) a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the

organization; and (c) a strong desire to maintain membership in the organization. Therefore,

Intrinsic Motivation 6

organizational commitment not only indicates an affective bond between the individual and the

organization but also willingness to stay with the organization. This study focuses on affective

organizational commitment. To be more specific for this study, the affective component of

organizational commitment is defined as the employees emotional attachment to, identification

with, and involvement in the organization. Employees with a strong affective commitment

continue employment with the organization because they want to do so (Meyer & Allen, 1991,

p. 67).

Organizational learning culture Organizational commitment. While the possible close

link between organizational learning culture and organizational commitment has been much said,

little identified study has yet investigated the relationship between the two constructs.

Organizational characteristics can enhance organizational commitment (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990).

Lim (2003) also reported that there were moderate but significant correlations between affective

organizational commitment and sub-constructs of organizational learning, ranging from .31

to .51. Thus, it is likely that the more employees perceive that an organization provides

continuous learning, dialogue and inquiry, team learning, established system, empowerment,

system connection, and strategic leadership, the higher they are psychologically attached to their

organization.

Hypothesis 3: Organizational learning culture will be positively related to organizational

commitment.

Perceived job complexity Organizational commitment. A meta-analysis by Mathieu and

Zajac (1990) found that job characteristics and job satisfaction can enhance organizational

commitment, which, in turn, affects the job performance variables (e.g., intention to leave,

turnover, and output measure). In general, productivity, commitment, and collegiality also

increased, when people held positive perceptions about their work context. People were more

productive, committed, and collegial when they were more motivated especially by the

satisfactions of the work itself (Amabile & Kramer, 2007). In particular, task autonomy has been

identified to impact employees organizational commitment (Dunham et al., 1994).

Hypothesis 4: Perceived job complexity will be positively related to organizational

commitment.

Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation is defined as any motivation that arises from the individuals positive

reaction to qualities of the task itself; this reaction can be experienced as interest, involvement,

curiosity, satisfaction, or positive challenge (Amabile, 1996, p.115). A necessary component of

intrinsic motivation is the individuals orientation or level of enthusiasm for the activity

(Amabile, 1988). A number of studies on individual creativity have focused on the importance of

intrinsic motivation (i.e., feelings of competence and self-determination on a given task) for

creativity (Amabile, 1988, 1996; Shalley, 1991; Shalley & Oldham, 1997). Regarding how

peoples perceptions of their work context affected creativity, people were more creative when

people saw their organizations as collaborative, cooperative, open to new ideas, able to evaluated

and develop new ideas fairly, clearly focused on an innovative vision, and willing to reward

creative work (Amabile & Kramer, 2007, p. 80).

Perceived job complexity Intrinsic motivation. It has been suggested that the way jobs

are structured contributes to employees intrinsic motivation and creative performance at work

Intrinsic Motivation 7

(e.g., Amabile, 1988). In particular, jobs that are designed to be complex and demanding (high

on autonomy and complexity) are expected to foster higher levels of intrinsic motivation than

will relatively simple, routine jobs (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). Complex jobs are those that

provide job incumbents with independence, opportunity to use a variety of skills, information

about their performance, and chance to complete an entire and significant piece of work (Baer,

Oldham, & Cummings, 2003). Task-based intrinsic motivation, which is performing a task for its

own sake because of enjoyment and interest in the task (i.e., flow), leads to being highly engaged

in the task, which helps to spur creative behaviors rather than relying on habitual responses

(Amabile, 1996; Csikszentmihalyi, 1996; Parker et al., 2001). Thus, when individuals are

intrinsically involved in their work, all of their attention and effort is focused on their jobs,

making them more persistent and more likely to consider different alternatives, which should

lead to higher levels of creativity (Shalley et al., 2000).

Hypothesis 5: Perceived job complexity will be positively related to intrinsic motivation.

Proactive personality Intrinsic motivation. While motivational orientation may be

partially shaped by the environment (i.e., organizational, social, job characteristics) (Amabile,

1983), there is also evidence suggesting a stable, trait-like nature (e.g., Amabile, Hill,

Hennessey, & Tighe, 1994). While there is an increasing research on proactivity and intrinsic

motivation, no study that examined the relationship between proactive personality and intrinsic

motivation has been found. As the two constructs have much commonality, a strong positive

relationship is expected. This study would be a starting point for the research between them in

the future.

Hypothesis 6: Proactive personality will be positively related to intrinsic motivation.

In summary, the conceptual model represents only an attempt to portray the relationships

among the factors related to organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation. It is far from

exhaustive. One contribution of this model is its integration of useful theory and research from

related literatures, such as organizational learning, personality, job design, organizational

commitment, and motivation.

Methods

Sample and data collection procedure will be described. Then, the information about four

measures will be elaborated below. Finally, the analytical strategy will be briefly discussed.

Sample and Data Collection Procedure

Four Fortune Global 500 companies participated in this study, representing diverse

industries: manufacturing, finance, construction, and trading. A convenience sampling approach

was used to insure representation within each of the demographic characteristics of importance

to this study (i.e., hierarchical level, job type, and length of LMX). A self-administered Internetbased online survey was used to obtain individual perceptions. Of the approximately 500

employees contacted by face-to-face, responses were received from 283 employees (Response

rate: 57%).

The demographic variables included: (a) gender, (b) age, (c) education level, (d)

hierarchical level, (e) the type of job, and (f) the length of a leader-follower relationship. Most

respondents were male (88%) in their 30s (95%) in manager or assistant manager position

Intrinsic Motivation 8

(98%). In terms of educational level, 44% of the respondents graduated from 4 year college, and

35% from graduate school. The length of the relationships with current supervisor was evenly

distributed across the categories: less than one year (21%), between one year to two years (23%),

between two to three years (16%), between three to five years (20%), and over five years (20%).

Classification by job types were as follows: 8% in marketing and sales, 13% in production, 9%

in engineering, 36% in research and development, 18% in information technology, 6% in

supporting function such as finance, HR, and legal, and 10% in others. In summary, most

respondents were highly educated male managers or assistant managers in their 30s.

Measures

All constructs used multi-item scales that have been developed and used in the Unites

States. The instruments were prepared for use in Korea using appropriate translation-backtranslation procedures. We used the survey questionnaire with a 5-point Likert-type scale

ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Organizational learning culture. To measure the organizational learning culture, as

suggested by Yang (2003) and Marsick and Watkins (2003), this study used seven items (i.e.,

OLC-15, 16, 10, 11, 15, 13, and 14) from Yang, Watkins, and Marsicks (2004) shortened

version of the dimensions of learning organization questionnaire (DLOQ), originally developed

by Watkins and Marsick (1997). The seven items represent each sub-construct (i.e., continuous

learning, dialogue and inquiry, team learning, empowerment, embedded system, system

connection, and strategic leadership). In effect, this treats organizational learning culture as a

single (uni-dimensional) construct. Coefficient alphas for the seven dimensions ranged from .68

to .83 (Yang et al., 2004). The reliability of seven items was .83 in this study. A sample item

included: In my organization, whenever people state their view, they also ask what others

think.

Proactive personality. The self-report measure of proactivity was a 10-item scale of the

proactivity personality survey (PPS) (Siebert et al., 1999), a shortened version of the instrument

originally developed by Bateman and Crant (1993). The correlation between the original full 17item scale and the shortened 10-item scale was .96. The reliability coefficient of the 10-item

scale was .86, which was similar to that of the full version (.88) (Siebert et al., 1993). The

internal consistency reliability was .85 in this study. A sample item was: I excel at identifying

opportunities.

Perceived job complexity. Six items from the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) (Hackman &

Oldham, 1980) were used to assess the challenges and complexity of employees jobs. Originally,

this instrument is composed of 15 items: three items for each of the five job characteristics (skill

variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback). The median alpha of the job

characteristics measures in Oldham and Cummings (1996) study was .68. Researchers in

previous studies argued that the sub-constructs of job characteristics are not independent of one

another (Dunham, 1976; Kulik, Oldham & Langner, 1988; Pierce & Dunham, 1978). In this

study, therefore, we used only six items: task significance (3 items) and autonomy (3 items).

Task significance and autonomy are considered to be more appropriate for measuring job

complexity. The internal consistency reliability was .80 in this study. A sample item included,

the job gives me considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do the work.

Intrinsic Motivation 9

Organizational commitment. Of the three characteristics of organizational commitment

(i.e., affective, continuance, and normative commitment), in this study, we used affective

organizational commitment, which was measured with the 8-item affective commitment scale

(Meyer, Allen, & Smith, 1993). Allen and Meyer (1996) reported that the median reliability of

many research was .85. In this study, the internal consistency reliability was .90. A sample item

was, I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization.

Intrinsic motivation. Tierney, Farmer, & Graen (1999) developed a 5-item measure for

employee intrinsic motivation, based on the work of Amabile (e.g., 1985). Items targeted

enjoyment for activities related to generating new ideas and activities. Whereas Tierney et al.,

reported that the internal consistency reliability was .74, it was .84 in this study. A sample item

was I enjoy coming up with new ideas for products.

Results

The results of the study are reported in four parts. First, the construct validity of each

measurement model is examined by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Second, the descriptive

statistics, correlations, and reliabilities of the reduced measurement model for the structural

model analyses are reported. Third, the hypothesized structural model is tested in comparison

with several alternative structural models. The best model is selected, based on both theoretical

considerations and a comparison of statistical indices. Finally, the results of the hypothesis

testing are addressed. All model tests (i.e., CFA and SEM) were based on the covariance matrix

and used maximum likelihood estimation as implemented in LISREL 8 (Joreskog & Sorbom,

1993).

Measurement Model Assessment

The purpose of assessing a models overall fit is to determine the degree to which the

model as a whole is consistent with the empirical data (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2000). CFA

was used to estimate convergent and discriminate validity of indicators of the five constructs:

organizational learning culture, proactive personality, perceived job complexity, organizational

commitment, and intrinsic motivation.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to estimate the quality of the factor

structure and designated factor loadings by statistically testing the fit between a proposed

measurement model and the data (Yang, 2005). The purpose of assessing a models overall fit is

to determine the degree to which the model as a whole is consistent with the empirical data

(Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2000). As a result of CFA, the overall measurement model

indicated an acceptable fit to the data ( 2 [584] = 2222.87; p = .00; RMSEA = .093; NNFI = .89;

CFI = .90; SRMR = .070). Table 1 shows the factor loadings of an overall CFA. All of the factor

loadings were over .50.

--------------------------------------------Insert Table 1 about here

---------------------------------------------

Intrinsic Motivation 10

Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, and Reliabilities

Table 2 presents the correlations among the five constructs and the reliabilities. All the

correlations indicated significant relationships (p < .01) among the constructs. Overall, most

correlations showed moderate and positive relationships among the five constructs. The

relationship between proactive personality and internal motivation was the highest (r = .70),

whereas the relationship between organizational learning culture and internal motivation was

comparatively weak (r = .27). All measures demonstrated adequate levels of reliability (.80 .90).

--------------------------------------------Insert Table 2 about here

--------------------------------------------Structural Model Assessment

The purpose of the structural model analysis is to determine whether the theoretical

relationships specified at the conceptualization stage are supported by the data (Diamantopoulos

& Siguaw, 2000). The adequacy of the structural model was estimated by comparing the

goodness-of-fit to the hypothesized model and the two additional nested models. The hypotheses

are examined through investigating the path coefficients and the total effect sizes of the

constructs in the final model.

Figure 1 illustrates the strengths of the relationships among the constructs, showing path

coefficients and overall model fit of the hypothesized structural model. The hypothesized model

indicated a good fit in all indices ( 2 [587] = 2226.09; p = .00; RMSEA = .093; NNFI = .89; CFI

= .90; SRMR = .075). All the paths among constructs were significant (t > 1.96). Overall, 44% of

the variance in organizational commitment was explained by organizational learning culture,

proactive personality, and perceived job complexity. About 54% of the variance in intrinsic

motivation was accounted for by organizational learning culture, proactive personality, and

perceived job complexity.

In addition, an alternative model was tested, excluding two direct paths: one from

organizational learning culture to organizational commitment and the other from proactive

personality to turnover intention (see Figure 2). While this alternative model exhibited a

marginally acceptable fit to the data ( 2 [589] = 2081.13; p = .00; RMSEA = .095; NNFI = .89;

CFI = .89; SRMR = .10), the percentages of the variances in the two variables were smaller than

those of hypothesized model (organizational commitment: 34%, intrinsic motivation: 32%).

--------------------------------------------Insert Figure 2 about here

---------------------------------------------

Intrinsic Motivation 11

In summary, the hypothesized model and the alternative model provided equivalent fits to

the data. Although the alternative model was better in terms of parsimony, the hypothesized

model was accepted as the final model, based on the consideration of the three criteria: (a)

goodness-of-fit, (b) estimated parameters with theoretical relationships, and (c) the law of

parsimony.

Hypotheses Testing

All the research hypotheses were supported, showing statistically significant path

coefficients (t < 1.96, p > .05). Organizational learning culture was found to be significantly

associated with perceived job complexity (H1: path coefficient = .21, t = 3.13) and

organizational commitment (H3: path coefficient = .38, t = 6.04). Proactive personality turned

out to be significantly related to job complexity (H2: path coefficient = .38, t = 5.44) and

intrinsic motivation (H5: path coefficient = .59, t = 8.72). Perceived job complexity was

significantly associated with organizational commitment (H4: path coefficient = .43, t = 6.34)

and intrinsic motivation (H6: path coefficient = .25, t = 3.99). Total indirect effects of

organizational learning culture and proactive personality on organizational commitment and

intrinsic motivation mediated by perceived job complexity were .25 and .15 respectively.

Discussion

The findings of this study are discussed on the basis of the hypothesized model, comparing with

previous research. Then, we will discuss the implications of this study for research and practice

in the field of HR/OB. In addition, the limitations of this study and recommendations for future

research are discussed. Finally, some conclusions are followed.

Findings of this Study

This study found that organizational learning culture, proactive personality, and perceived

job complexity contribute to organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation. More

specifically, employees exhibited the highest organizational commitment, when the organization

had a higher learning culture. Employees were more intrinsically motivated, when they showed

higher proactive personality. The perception of their job complexity partially mediated the

relationships between the antecedents (i.e., organizational learning culture and proactive

personality) and the consequences (i.e., organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation).

Overall, 44% of the variance in organizational commitment was explained by organizational

learning culture, proactive personality, and perceived job complexity. About 54% of the variance

in intrinsic motivation was accounted for by organizational learning culture, proactive

personality, and perceived job complexity.

Organizational learning culture. The more employees perceive that an organization

provides continuous learning, dialogue and inquiry, team learning, established system,

empowerment, system connection, and strategic leadership, the higher they are psychologically

attached to their organization. Moreover, when employees perceive that an organization provides

better organizational learning culture, they are more likely to realize job complexity, which, in

turn, affects organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation. An increasingly uncertain

Intrinsic Motivation 12

environment requires an organizational learning culture and knowledge workers prefer complex

jobs to simple and routine work (Parker et al., 2001). Organizational learning culture can

significantly influence job complexity in many ways. For instance, enriched forms of job design

are most appropriate where uncertainty is high (Parker et al., 2001), and autonomy has been

identified to be particularly salient for knowledge workers (Janz et al., 1997).

Proactive personality. This study replicated the results of the previous studies that when

employees have higher in proactive personality, they tended to be highly motivated intrinsically.

Employees with higher in proactive personality were likely to perceive higher job complexity.

That is, proactive people tend to rate job characteristics as more enriched than do less positively

disposed individuals (Brief, Butcher, & Roberson, 1995; James & Jones, 1980; Judge et al.,

1998; Judge et al., 2000; Kraiger, Billings, & Isen, 1989; Necowitz & Roznowski, 1994; Parker

et al., 2006). One of the new findings of this study is the strong and positive relationship between

proactive personality and intrinsic motivation. While there were a lot of similarities between the

two constructs, as a result of CFA, they found to be distinctive.

Perceived job complexity. In this study, perceived job complexity was significantly related

to organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation, playing a role as a mediator. When

employees perceived higher job complexity, more specifically, higher task significance and

autonomy, employees are more likely to conduct their work in active and creative ways. Results

of previous studies tend to be generally consistent with the above results (e.g., Amabile &

Gryskiewicz, 1989; Csikszentmihalyi, 1996; Hatcher et al., 1989; Farmer, Tierney, & KungMcIntyre, 2003; Oldham & Cummings, 1996; Shalley et al., 2004; Parker et al., 2001). Complex

and demanding jobs are expected to foster higher levels of intrinsic motivation than will

relatively simple, routine jobs (Hackman & Oldham, 1980; Shalley & Gibson, 2004). Thus, this

study confirmed the findings of the previous research.

Implications

Replicating previous research and examining new findings, this study takes the multilevel

efforts: organizational level (organizational learning culture) as well as job (job complexity) and

individual level (proactive personality). With regard to the theoretical contributions, this study

linked organizational learning, personality, job design, organizational commitment, and

motivation research. To be more specific, whereas the links between job design, organizational

commitment and motivation have been widely investigated, little research has explored the

antecedents such as organizational learning culture and proactive personality. The practical

implications for HR/OD professionals who develop relevant practices for the purpose of

enhancing organizational commitment and employee motivation are suggested below.

As long as the knowledge-based economy and the war for talent continue, more and more

firms will try to become employers of choice (Gubman, 2004). And firms that fail to secure a

loyal base of workers constantly place an inexperience group of non-cohesive units on the front

lines of their organization, much to their own detriment (Guthrie, 2001). In order effectively to

attract, motivate, and retain talented employees, many firms try to become employers of choice

defined as firms that are always the first choice of first-class candidates due to their status and

reputation in terms of corporate culture and HR practices (Sutherland, Torricelli, & Karg, 2002).

In other words, employers of choice are those organizations that outperform their competition in

attracting, developing, and retaining people with business-required talent. They achieve this

Intrinsic Motivation 13

reputation through innovative and compelling HR practices that benefit both employees and their

organizations. Thus, it is critically important to monitor employees job satisfaction, motivation,

and organizational commitment level. In this vein, periodical survey-feedback approach is highly

recommended. If fact, research has established a direct link between employee retention rates

and sales growth and companies that are cited as one of the 100 Best Companies to Work For

routinely outperform their competition on many other financial indicators of performance

(Fulmer, Gerhart, & Scott, 2003).

Managers and HR/OD professionals can support employees organizational commitment in

the organizational level as well as in job and individual level by developing, improving, and

delivering the relevant practices. HR/OD practitioners can support managers by providing

relevant HR practices and services: changing organizational culture, enhancing organizational

learning, developing transformative and supportive leadership, designing more challenging,

complex, autonomous jobs, and hiring and retaining proactive employees. However, changing

one factor alone (e.g., hiring proactive employees) will not help organizational commitment and

intrinsic motivation, if other factors are not in place (e.g., organizational learning culture).

Therefore, HR practices should not be implemented alone. Rather, each practice should be

delivered and applied in a concerted way and in a holistic perspective. In other words, enhancing

organizational commitment of employees will require an integrated strategy, incorporating

elements of culture management, organizational structure, job redesign, and leadership

development. This is by no means an easy feat, which is why organizations that are successful in

building this type of organization are likely to have a sustainable competitive advantage.

Limitations and Future Research

In terms of methodology, this study has several potential limitations. First, because this

study, like most creativity studies, relied on self-reported and or reflective recollection of the

indicators of the constructs in this study by employees who volunteered their participation.

Second, this empirical study confines itself to cross-sectional survey method, which leaves room

for speculation with regard to causality among the variables. In addition, the sample of this study,

consisting most of highly educated male managers, is likely restricted to a certain group with

similar demographic characteristics (e.g., male of relatively high cognitive ability).

To solve the limitations above, methodologically, future research needs to be based on

objective indicators and multiple sources. In addition, to increase generalizability of the present

study, more studies in various industries representing diverse demographic cohorts are needed.

More specifically, this study focused on knowledge workers with higher educational level. The

results might vary by the cohorts in different educational levels. More research in different

educational background is recommended.

Conclusion

A good workplace is believed to produce higher quality products, support more innovation,

have the ability to attract more talented people, and experience less resistance to change and

lower turnover costs, all of which translate directly into a better bottom line (Joo & McLean,

2006; Levering, 1996). Conversely, dissatisfied workers may be able to solve their problems by

leaving the job. Thus, it is imperative to improve organizational commitment and intrinsic

Intrinsic Motivation 14

motivation through positive organizational learning culture and job design. HR/OD professionals

can help their employees win the race of sustained competitive advantages.

Intrinsic Motivation 15

RERERENCES

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. 1996. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the

organization: An examination of construct validity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 49(3),

252-276.

Amablie, T. M. 1988. A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in

Organizational Behavior, 10: 123-168.

Amabile, T. M. 1995. Discovering the unknowable, managing the unmanageable. In C. M. Ford

& D. A. Gioia (Eds.), Creative action in organizations: Ivory tower visions and real world

voices (pp. 77-82). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Amablie, T. M. 1996. Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity.

Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Amabile, T. M., & Conti, R. 1999. Changes in the work environment for creativity during

downsizing. Academy of Management Journal, 42: 630-640.

Amabile, T. M., & Gryskiewicz, N D. 1989. The creative environment scales: Work environment

inventory. Creativity Research Journal, 2: 231-252.

Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. J. 2007. Inner work life: Understanding the subtext of business

performance. Harvard Business Review, 85(5), 72-83.

Andrew, F M., & Farris, G. F. 1967. Supervisory practices and innovation in scientific teams.

Personnel Psychology, 20: 497-575.

Angle, H., & Perry, J. (1983). Organizational commitment: Individual and organizational influences.

Work and Occupations, 10(2), 123-146.

Ashford, S. J., & Cummings, L. L. 1985. Proactive feedback seeking: The instrumental use of

the information environment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 58: 67-79.

Baer, M., Oldham, G. R., & Cummings, A. 2003. Rewarding creativity: When does it really

matter? The Leadership Quarterly, 14: 569-586.

Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. 1993. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A

measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(2): 103-118.

Beck, K., & Wilson, C. 2000. Development of affective organizational commitment: A crosssequential examination of change with tenure. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(1), 114-136.

Bedeian, A., Kemery, E., & Pizzolatto, A. 1991. Career commitment and expected utility of present

job as predictors of turnover intentions and turnover behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior,

39(3), 331-343.

Beyerlein, M. M., Johnson, D. A., & Beyerlein, S. T. 1999. Advances in interdisciplinary

studies of work teams. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Bluedorn, A. D. (1982). A unified model of turnover from organizations. Human Relations, 35(2),

135-153.

Confessore, S. J., & Kops, W. J. 1998. Self-directed learning and the learning organization:

Examining the connection between the individual and the learning environment. Human

Resource Development Quarterly, 9(4): 365-375.

Crant, J. M. 2000. Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3): 435-62.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1996. Creativity: Flow and psychology of discovery and invention. New

York: Harper Perennial.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Getzel, J. W. 1988. Creativity and problem finding. In F. H. Farley &

R. W. Neperud (Eds.), The foundations of aesthetics, art, and art education (pp. 91-106).

New York: Praeger.

Intrinsic Motivation 16

Damanpour, F. 1995. Is your creative organization innovative? In C. M. Ford & D. A. Gioia

(Eds.), Creative action in organizations: Ivory tower visions and real world voices (pp.

125-130). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dansereau, F., Cashman, J., & Graen, G. 1973. Instrumentality theory and equity theory as

complementary approaches in predicting the relationship of leadership and turnover among

managers. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 10(2): 184-200.

Dansereau, F., Graen, G., & Haga, W. J. 1975. A vertical dyad approach to leadership within

formal organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 13: 46-78.

Deluga, R. J. 1998. Leader-member exchange quality and effectiveness ratings: The role of

subordinate-supervisor conscientiousness similarity. Group and Organization

Management, 23: 189-216.

Drucker, P. 1988. The coming of the new organizations. Harvard Business Review, JanuaryFebruary, 45-53.

Dunegan, K. J., Duchon, D., & Uhl-Bien, M. 1992. Examining the link between leader-member

exchange and subordinate performance: The role of task analyzability and variety as

moderators. Journal of Management, 18(1): 59-76.

Farmer, Tierney, & Kung-McIntyre. 2003. Employee creativity in Taiwan: An application of role

identity theory. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5): 618-630.

Ford, C. M. 1995. Creativity is a mystery: Clues from the investigators notebooks. In C. M.

Ford & D. A. Gioia (Eds.), Creative action in organizations: Ivory tower visions and real

world voices (pp. 12-49). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fried, Y., & Ferris, G.R. 1987. The validity of the Job Characteristics Model: A review and meta

analysis. Personnel Psychology, 40: 287-322.

Fulmer, I. S., Gerhart, B., & Scott, K. S. 2003. Are the 100 best better? An empirical

investigation of the relationship between being a great place to work and firm performance.

Personnel Psychology, 56(4), 965-993.

Gardner, H. 1993. Frames of Mind: The theory of multiple intelligences, New York: Basic

Books.

Garvin, D. A. 1993. Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 71(4): 78-91.

George, J. M., & Zhou, J. 2001. When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related

to creative behavior: An interactional approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3):

513-524.

Gubman, E. 2004. From engagement to passion for work: The search for the missing person.

Human Resource Planning, 27(3), 42-46.

Guthrie, J. P. 2001. High-involvement work practices, turnover, and productivity: Evidence from

New Zealand. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 180-190.

Joo, B., & McLean, G. N. 2006. Best employer studies: A conceptual model from a literature

review and a case study. Human Resource Development Review, 5(2): 228-257.

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., & Locke, E. A. 2000. Personality and job satisfaction: The mediating

role of job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(2): 237-249.

Koch, J., & Steers, R. 1978. Job attachment satisfaction, and turnover among public employees.

Journal of Vocational behavior, 12(2), 119-128.

Lee, C. H., & Bruvold, N. T. 2003. Creating value for employees: investment in employee

development. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(6), 981-1000.

Intrinsic Motivation 17

Levering, R. 1996. Employability and trust. Conference Board meeting, Chicago, 12

September, 1996. Retrieved August 3, 2007, from

http://resources.greatplacetowork.com/article/pdf/building-trust.pdf

Madjar, N., Oldham, G. R., & Pratt, M. G. 2002. Theres no place like home? The contributions

of work and nonwork creativity support to employees creative performance. Academy of

Management, 45(4): 757-767.

Marsick, V. L., & Watkins. K. E. 2003. Demonstrating the value of an organizations learning

culture: The dimensions of the learning of the learning organization questionnaire.

Advances in Developing Human Resources, 5(2): 132-151.

Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. 1990. A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and

consequences of organizational commitment. Psychology Bulletin, 108(2), 171-194.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. 1991. A three component conceptualization of organization commitment.

Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61-89.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. 1997. Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Morgeson, F. P. 2005. The external leadership of self-managing teams: Intervening in the

context of novel and disruptive events. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3): 497-508.

Morrison, E. W. 1993. Newcomer information seeking: Exploring types, modes, sources, and

outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 36: 557-589.

Mowday, R. 1998. Reflections on the study and relevance of organizational commitment. Human

Resource Management Review, 8(4), 387-401.

Mowday, R., Porter, L., & Dubin, R. 1974. Unit performance, situational factors and employee

attitudes in spatially separated work unites. Organizational Behavior and Human

Performance, 12(2), 231-248.

Mowday, R., Steers, R., & Porter, L. 1982. Employee-organization linkages: The psychology of

commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. New York: Academic Press.

Mumford, M. D., Baughman, W. A., Uhlman, C. E., Costanza, D. P., & Threlfall, K. V. 1993.

Personality variables and skill acquisition: Performance while practicing a complex task.

Human Performance, 6(4): 345-481.

Mumford, M. D., Scott, G. M., Gaddis, B., & Strange, J. M. 2002. Leading creative people:

Orchestrating expertise and relationships. Leadership Quarterly, 13(6): 705-750.

Oldham, G. R., & Cummings, A. 1996. Employee creativity: Personal and contextual factors at

work. Academy of Management Journal, 39(3): 607-634.

Organ, D. W. 1990. The motivational basis of organizational citizenship behavior. In B. M. Staw

& L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, 12: 43-72.

Parker, S. K. 1998. Enhancing role breadth self-efficacy: The roles of job enrichment and other

organizational interventions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(6): 835-852.

Parker, S. K., Wall, T. D., & Cordery, J. L. 2001. Future work design research and practice:

Towards an elaborated model of work design. Journal of Occupational and

Organizational Psychology, 74(4): 413-440.

Parker, S. K., Wall, T. D., & Jackson, P. R. 1997. Thats not my job: Developing flexible

employee work orientations. Academy of Management Journal, 40: 899-929.

Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., & Turner, N. 2006. Modeling the antecedents of proactive

behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3): 636-652.

Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. 1996. Proactive socialization and behavioral self-management.

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 48(3): 301-323.

Intrinsic Motivation 18

Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. 1994. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of

individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3): 580607.

Seibert, S. E., Crant, J. M., & Kraimer, M. L. 1999. Proactive personality and career success.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(3): 416-427.

Senge, P. M. 1990. The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New

York: Doubleday.

Shalley, C. E. 1991. Effects of productivity goals, creativity goals, and personal discretion on

individual creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(2): 179-185.

Shalley, C. E., & Gibson, L. L. 2004. What leaders need to know: A review of social and

contextual factors that can foster or hinder creativity. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1):

3353.

Shalley, C. E., Gibson, L. L., & Blum, T. C. 2000. Matching creativity requirements and the

work environment: Effects on satisfaction and intentions to leave. Academy of

Management Journal, 43(2): 215-223.

Shalley, C. E., Zhou, J., & Oldham, G. R. 2004. The effects of personal and contextual

characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? Journal of Management,

30(6): 933-958.

Sparrowe, R. T., & Liden, R. C. 1997. Process and structure in leader-member exchange.

Academy of Management Review, 22(2): 522-552.

Steers, R. 1977. Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 22(1), 46-56.

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. 1999. The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In R.

J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 3-15). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Sutherland, M. M., Torricelli, D. G., & Karg, R. F. 2002. Employer-of-choice branding for

knowledge workers. South African Journal of Business Management, 33(4), 13-20.

Thompson, J. A. 2005. Proactive personality and job performance: A social capital perspective.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5): 1011-1017.

Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. 2002. Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and

relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6): 11371148.

Tierney, P., Farmer, S. M., & Graen, G. B. 1999. An examination of leadership and employee

creativity: The relevance of traits and relationships. Personnel Psychology, 52(3): 591-620.

Unsworth, K. L., & Parker, S. K. 2003. Proactivity and innovation: Promoting a new workforce

for the new workplace. In D. Holman, T. D. Wall, C. W. Clegg, P. Sparrow, & A. Howard

(Eds.). The new workplace: A guide to the human impact of modern working practices

(pp. 175-196). Chicester, England: Wiley.

Wanberg, C. R., Welsh, L. & Hezlett, S. 2003. Mentoring: A review and directions for future

research. In J. Martocchio & J. Ferris (Eds.) Research in Personnel and Human

Resources Management, 22: 39-124. Oxford: Elsevier Science LTD.

Wehner, L., Csikzentmihalyi, M., & Magyari-Beck, I. 1991. Current approaches used in studying

creativity: An exploratory investigation. Creativity Research Journal, 4: 261-271.

Intrinsic Motivation 19

West, M., & Farr, J. 1990. Innovation at work. In M. West & J. Farr (Eds.), Innovation and

creativity at work: Psychological and organizational strategies (pp. 3-13). New York:

Wiley.

Williams, W. M., & Yang, L. T. 1999. Organizational creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.),

Handbook of creativity (pp. 373-391). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Woodman, R.W., Sawyer, J.E., & Griffin, R.W. (1993). Toward a theory of organizational

creativity. Academy of Management Review, 18(2): 293-321.

Zhou, J. 2003. When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: Role of

supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback, and creative personality. Journal of

Applied Psychology. 88(3): 413-422.

Zhou, J., & George, J. M. 2003. Awakening employee creativity: The role of leader emotional

intelligence. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(4-5): 545-568.

Zhou, J., & Shalley, C. E. 2003. Research on employee creativity: A critical review and

directions for future research. Research in Personnel and Human Resources

Management, 12: 165-217.

Intrinsic Motivation 20

TABLE 1

Factor Loadings

OLC-1

OLC-2

OLC-3

OLC-4

OLC-5

OLC-6

OLC-7

PP-1

PP-2

PP-3

PP-4

PP-5

PP-6

PP-7

PP-8

PP-9

PP-10

PJC-1

PJC-2

PJC-3

PJC-4

PJC-5

PJC-6

AOC-1

AOC-2

AOC-3

AOC-4

AOC-5

AOC-6

AOC-7

AOC-8

IM-1

IM-2

IM-3

IM-4

IM-5

Note, n = 283

Organizational

Learning Culture

.63

.66

.61

.77

.63

.70

.76

Proactive

Personality

Perceived Job

Complexity

Organizational

Commitment

Intrinsic

Motivation

.66

.77

.56

.59

.72

.69

.66

.69

.68

.68

.72

.65

.71

.71

.72

.64

.69

.71

.63

.59

.87

.88

.77

.91

.79

.77

.71

.78

.82

Intrinsic Motivation 21

TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics and Reliabilities

N

283

Mean

3.29

S.D

.63

1

(.83)

2. Proactive Personality

283

3.65

.49

.32**

(.85)

3. Perceived Job

Complexity

4. Organizational

Commitment

5. Intrinsic Motivation

283

3.75

.53

.34**

.45**

(.80)

283

3.28

.76

.53**

.32**

.56**

(.90)

283

3.74

.64

.27**

.70**

.52**

.33**

1. Organizational

Learning Culture

Note, the phi matrix from CFA; * p < .05;

**

p < .01;

(.84)

Intrinsic Motivation 22

FIGURE 1

A Conceptual (Hypothesized) Model

Organizational

Learning

Culture

H3

Organizational

Commitment

.38

H1

H4

.21

.43

Perceived Job

Complexity

Proactive

Personality

H2

H6

.38

.25

H5

.59

significant path; * p < .05 (t > 1.96);

Intrinsic

Motivation

Non-significant path

Intrinsic Motivation 23

FIGURE 2

Alternative (Full Mediation) Model

Organizational

Learning

Culture

Organizational

Commitment

.25

.58

Perceived Job

Complexity

Proactive

Personality

.43

significant path; * p < .05 (t > 1.96);

.56

Intrinsic

Motivation

Non-significant path

Вам также может понравиться

- HR Om11 ch16Документ63 страницыHR Om11 ch16Anisa WPОценок пока нет

- Debondt 2020Документ10 страницDebondt 2020Atiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- BRM OkДокумент2 страницыBRM OkAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- (Effective From Fall 2020) - 1st Semester: / & SameДокумент2 страницы(Effective From Fall 2020) - 1st Semester: / & Sametheict mentorОценок пока нет

- LMS REPORT - 6th Dec 2020 EveningДокумент1 страницаLMS REPORT - 6th Dec 2020 EveningAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Bio Data FormДокумент1 страницаBio Data FormAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Bio Data FormДокумент2 страницыBio Data FormAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- 1623764224business Plan April 2021Документ6 страниц1623764224business Plan April 2021Atiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Financial Risk ManagementДокумент19 страницFinancial Risk ManagementAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Financial Management For Decision MakersДокумент9 страницFinancial Management For Decision MakersAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- LMS Report - Atiq 17-03-2021Документ1 страницаLMS Report - Atiq 17-03-2021Atiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Sample Paper Midterm Fall 2021Документ1 страницаSample Paper Midterm Fall 2021Atiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorДокумент15 страниц6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Self Assessment Report: Cover LetterДокумент5 страницSelf Assessment Report: Cover LetterAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- BBA Stream II III IVДокумент27 страницBBA Stream II III IVAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Bio-Data New StudentsДокумент1 страницаBio-Data New StudentsAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Solution Manual Of Financial Management By Brigham Filetype PdfДокумент3 страницыSolution Manual Of Financial Management By Brigham Filetype PdfAtiq Ur Rehman9% (11)

- Tutorial - Get Running With AMOS GraphicsДокумент17 страницTutorial - Get Running With AMOS GraphicsTiago ZorteaОценок пока нет

- Management Terms DictionaryДокумент50 страницManagement Terms DictionaryKazi Nazrul IslamОценок пока нет

- Aphr 12030Документ21 страницаAphr 12030Atiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- NafeesДокумент9 страницNafeesAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Seminar On: Practical Implementation of Strategic ManagementДокумент1 страницаSeminar On: Practical Implementation of Strategic ManagementAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Job Opportunities: Program Officer, MER Islamabad QualificationsДокумент12 страницJob Opportunities: Program Officer, MER Islamabad QualificationsAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- 6.Management-Factors Affecting Academic Staff Turnover Intentions-Mulu Berhanu HunderaДокумент14 страниц6.Management-Factors Affecting Academic Staff Turnover Intentions-Mulu Berhanu HunderaImpact JournalsОценок пока нет

- Teqnique of PharaprasingДокумент2 страницыTeqnique of PharaprasingMahesa NasutionОценок пока нет

- Equivalence 2013 ICAPДокумент1 страницаEquivalence 2013 ICAPhmad9ranaОценок пока нет

- TBAD r9b Watkins. DLOQ Demonstrating ValueДокумент21 страницаTBAD r9b Watkins. DLOQ Demonstrating ValueAtiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Students Fees List QA Version 32472014301046Документ7 страницStudents Fees List QA Version 32472014301046Atiq Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- The Match Between University Education and Graduate Labour Market Outcomes (Education-Job Match)Документ144 страницыThe Match Between University Education and Graduate Labour Market Outcomes (Education-Job Match)Rashi KaushalОценок пока нет

- Recruitment & SelectionДокумент74 страницыRecruitment & SelectionJitender YadavОценок пока нет

- Making A Modern Leader in Europe UKДокумент22 страницыMaking A Modern Leader in Europe UKDiego MartínОценок пока нет

- School Form 7 (SF7) School Personnel Assignment List and Basic ProfileДокумент3 страницыSchool Form 7 (SF7) School Personnel Assignment List and Basic ProfileMary Kate Fatima BautistaОценок пока нет

- Assignment Case StudyДокумент3 страницыAssignment Case StudyMairene CastroОценок пока нет

- Factories Act, 1948: OBJECTIVE: The Main Objective of The Act Is To Ensure Adequate SafetyДокумент28 страницFactories Act, 1948: OBJECTIVE: The Main Objective of The Act Is To Ensure Adequate SafetyBidyashree PatnaikОценок пока нет

- 2020 FC Aquatic Program Budget TemplateДокумент10 страниц2020 FC Aquatic Program Budget TemplateJayson CustodioОценок пока нет

- HRM Full AssignmentДокумент17 страницHRM Full AssignmentAhmed Sultan100% (1)

- Employees State Insurance Act - Mod 6Документ10 страницEmployees State Insurance Act - Mod 6ISHAAN MICHAELОценок пока нет

- Conflict ManagementДокумент310 страницConflict Managementvhuthuhawe100% (1)

- Human Resource Planning EssentialsДокумент10 страницHuman Resource Planning EssentialsRashmi ShiviniОценок пока нет

- Scientific ManagementДокумент24 страницыScientific Managementdipti30Оценок пока нет

- Lori Howard Tort Claim Against Frank G. Bowne and Post Falls PDДокумент1 страницаLori Howard Tort Claim Against Frank G. Bowne and Post Falls PDWilliam N. GriggОценок пока нет

- Adl-01 Principles and Practices of ManagementДокумент24 страницыAdl-01 Principles and Practices of Managementmbanlj100% (6)

- Sek 20Документ25 страницSek 20Salam Salam Solidarity (fauzi ibrahim)Оценок пока нет

- PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENTДокумент1 страницаPRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENTJothiEeshwarОценок пока нет

- Training DesignДокумент5 страницTraining DesignVicky CatubigОценок пока нет

- FICCI - Ernst & Young ReportДокумент48 страницFICCI - Ernst & Young ReportGlobal_Skills_SummitОценок пока нет

- Healthand SafetypolicyДокумент1 страницаHealthand SafetypolicyBen Heath-ColemanОценок пока нет

- 19 - Pboap Vs DoleДокумент17 страниц19 - Pboap Vs DoleMia AdlawanОценок пока нет

- Ncert Sol Class 12 Business Studies ch2 PrinciplesДокумент11 страницNcert Sol Class 12 Business Studies ch2 PrinciplesAHMED AlpОценок пока нет

- TeleTech Philippines - Welcome PacketДокумент6 страницTeleTech Philippines - Welcome PacketMaria Leonisa Sencil-TristezaОценок пока нет

- Adult Education in Philippine Higher Education: Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University La Union, PhilippinesДокумент25 страницAdult Education in Philippine Higher Education: Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University La Union, PhilippinesNereo ReoliquioОценок пока нет

- Tesco Case Study Tesco Case Study AssignДокумент5 страницTesco Case Study Tesco Case Study AssignSamuel kwateiОценок пока нет

- COMPARATIVE STUDY OF HR PRACTICES OF COAL INDIA LTD. AND INFOSYSДокумент17 страницCOMPARATIVE STUDY OF HR PRACTICES OF COAL INDIA LTD. AND INFOSYSJaspreet Kahlon0% (1)

- Ielts Speaking: Vocabulary & Sample AnswersДокумент16 страницIelts Speaking: Vocabulary & Sample AnswersMy Linh Huynh100% (1)

- Frequently Asked Questions On Intellectual Disability and The AAIDD DefinitionДокумент6 страницFrequently Asked Questions On Intellectual Disability and The AAIDD DefinitionNomar CapoyОценок пока нет

- Poverty, Inequality and Social Protection in LebanonДокумент48 страницPoverty, Inequality and Social Protection in LebanonOxfamОценок пока нет

- Operations Management ScriptДокумент4 страницыOperations Management ScriptmichelleОценок пока нет

- Indg 303Документ8 страницIndg 303Nandang KuroshakiОценок пока нет