Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Busch-On The Horizontal and Vertical Presentation of Musical Ideas and On Musical (1985)

Загружено:

BrianMoseleyОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Busch-On The Horizontal and Vertical Presentation of Musical Ideas and On Musical (1985)

Загружено:

BrianMoseleyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Cambridge University Press

http://www.jstor.org/stable/946351 .

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Tempo.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ON

THE

AND

HORIZONTAL

VERTICAL PRESENTATION

OF

MUSICAL

IDEAS

and

on

Musical

Space

(I)

Regina

Busch

'HIS OWN ATTEMPTSAT EXPLANATION,just like his compositional work, lend themselves to

misunderstanding'.This opinion dominatesWebern literaturenow as in the past, though

naturallynot always in this formulationof Dohl's.' Sometimeswe readof contradictions,

of imprecisions;errorsof fact or of mentalprocessescanbe 'demonstrated';and,depending

on the particularauthor'sfield of interest and study, these are treatedwith indulgenceor

gentle annoyance, with indignation or knowing dismissal. Who could expect of a

composer-a composer, moreover, like Webern: naive, at times culpably naive,

withdrawn from reality; with a music so 'abstract',so in need of help or redemptionby

meansof interpretation-who could expect of sucha composerpertinentandconsistent,or

at least apt, music-theoreticalconceptsor utterances?Hardlyanyone,in fact, seemsto have

dared to expect this kind of thing of Webern so far. That this might indeedinvolve some

daring can be recognized from the conditions, the fuss, and circumstancewith which

Webern is approached.Whether they have sprungfrom the soil of serialmusicor not, all

the systematicinvestigations,the numberingof note-rows, classifyingof pitches,durations

and so on, considerations of 'structure' (many investigations, too, of 'form', of

symmetries)-they all seem like precautionsagainst the music. Since the music is not

trusted,the traditionalmusic-theoreticalconceptspresentedby Webern (and Schoenberg,

too) are also regardedas unsuitedfor coping with the music. Instead,attemptsare made

using, for instance, the idea of a cell (usually a three-note basic cell) and its

metamorphoses-an idea which is at leastas anachronisticas the traditionalones, is scarcely

strongenough to bear the burdenof explication,andis exactly as vulnerableto criticismon

scientific and ideological grounds as a serious preoccupation with Weber's own

statementsis alleged to be.

It may be that everything about Webern invites misunderstanding;

it may be that the

musicand the attemptsat explanationget in each other'sways. The musicevidently seems

1Friedhelm D6hl, 'Zum Formbegriff Weberns. Weberns Analyse des Streichquartetts op.28 nebst einigen

Bemerkungen zu Weberns Analyse eigener Werke' (On Webern's Concept of Form. Webern's Analysis of the

String Quartet op.28, together with some observations on Webern's analysis of his own works), in Osterreichische

Musikzeitschrift27 (1972), pp.131-148, especially p.137. Cf.also D6hl's 'Weberns Beitrag zur Stilwende der neuen

Musik' (Webern's contribution to the change in style of the New Music) in Berlinermusikwissenschaftliche

Arbeiten

Vol.12 (Munich-Salzburg 1976), p.337ff.

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HORIZONTAL AND VERTICAL

to frighten people; at all events it does not make things easy for them. It has not become

familiar, or at least not self-evident, even to experienced interpreters.

Above all, it is hardlyloved-and the blame for this cannotlie only with the fact thatit

is mostly performed badly and without understanding.It seems only to give genuine

pleasureto a very few, and often not even then as music but more as an elitist occasion.

Access to this music is thereforecertainlynot easy. But providedthat one doesnot propose

simply to forget, displace, ignore or proscribeit, but regardsit as interestingand full of

promise(not merely significant),one will nonethelesshave to involve oneself andactively

come to terms with it. Webern's own statementscould facilitate this access and provide

helpfulcommentaries,especiallyif one does not get on too well with the scores,but only as

long as they are not robbed of their possible causes of misunderstandingand their

contradictions.Holding fast to the inconsistenciescould turn out to be more revealing,as

far as the understandingof his music and its general evaluation are concerned, than the

applicationto it of decisive interpretationmodels in which problemsand difficulties are

degradedinto errorsandaestheticflaws. Forit cannotsurelybe a matterof ascribinga place

in (musical) history to Webern and then consigninghim to the historical records?

Webern's 'attemptsat explanation'have in general sufferedthe samefate as his music:

they havebeen kept at a safedistance,or repelledaltogether.The vocabularymainlyusedin

talkingand writing about the music is peculiarlyneutral,cautious-one might almostsay

timid. The concepts have a sterilizingeffect upon the way the musicis heard,bluntingthe

effect of the sounds,blurringthe music.At any rate-and thiscan even be heardin the most

obscure interpretation-they are remote from the music and inadequateto it. They only

mirror the perplexity that Webern's music causedand causes;they do not removeit. The

conviction (which is widely disseminated)that one cannot, on the other hand,get on well

with or close to the music with 'traditional' music-theoretical concepts or ways of

describingmusic-and these after all includeWebern'spreviously-mentionedattemptsat

explanation;attemptswhich may not even be intendedto explain!-is in no way basedon

the actualexperience of the music. One may even askwhetherit reallywas thismusic-or,

more generally, non-tonal music-that provoked the re-examination, modification, or

even the throwing overboardof the concepts.

It is nonsensicalor falsifying-so it has been argued, for example, in connexion with

Webern-to apply the traditionalconcept of a period (a concept directed above all at

regularity) to him; it is similarlyheld inappropriateto speak of sonata form, unless one

means an ABA form in the most general sense-that is, once again in that neutral, and

perhapsalso neutralizing,sense. This kind of argumentcan be appliedconcerningvirtually

every music-theoreticalconcept to almostevery music:a consequenceof the naturallyand

inevitablycomplex relationshipof theory to thatof which it is a theory.Whether, over and

above this, the relationshipbetween musical circumstancesand 'traditional'concepts is

especiallyproblematicin the case of Webern, andwhy andto what extent, would firstneed

to be found out. Be that as it may, Weber, Schoenberg,Berg (and some of their pupils)

have spokenand written about their own music with the help of these concepts, to which

they, too, have linked concrete musical experiences concerning 'traditional'music. To

renouncethe use of this terminologybefore testingit-and this would, after all, also mean

giving up certain ways of thinkingand hearing-would be a luxury, or a sacrifice that

would only be worth while if one thenunderstoodthe musicandenjoyedit better. And that

is by no meanscertain:up to now, at any rate, we havenot got any furtherthanintellectual

satisfaction.To expect no more from a musicologicalengagementwith Webern,however,

is surelyalso an exampleof'stupidity in music',in the senseof Eisler'scategoryas described

by Karoly Csipak.2

2German'Dummheit'-see Karoly Csipak, 'Problemeder Volkstiimlichkeitbei HannsEisler'(HannsEislerand

the problem of popularity)in Berliner

ArbeitenVol. 11 (Munich1975);Karoly Csipak, 'Was

musikwissenschaftliche

heisst "Dummheit in der Musik"?Uberlegungenzu HannsEislersMusikdenken'(What does 'stupidityin music'

mean?Reflectionson HannsEisler'smusicalthinking),in Notizbuch5/6: Musik,edited by ReinhardKapp(BerlinVienna, 1982), pp.175-202.

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Yes!

TEMPO

It is also partof the characteristicway of dealingwith the terminologyof Schoenberg's

Viennese school to proceed, as it were, globally (another method of preservingone's

distance),especially in the case of concepts which had not up till then been establishedas

music-theoreticalones in the narrower sense: musical space, musical idea, comprehensibility, coherence, emancipationof dissonance,timbre, musicallogic, for example. The

fact thatsuchconceptsoccurin the work of differentauthors-Schoenberg, Webem, Berg,

Ratz, Spinner,Stein, Rufer,and out to the most remotecircles-is relatedto the formation

of this school, but it also says somethingabout their statusas terms.On the other hand,the

varying uses and to some extent variable meaningsof the concepts stand in the way of

precisedefinitions,and are a temptationto regardthem in each case as no more andno less

thana privateterminology:one, however, which-especially in the case of Schoenberg-is

not denied a claim to theoretical significanceand far-reachingeffect.3

Proceedingglobally:that meansthat virtuallynothingis known about the evolutionof

even a single one of these concepts in the musical thinkingof a composer-neither of the

'history' of the concept itself nor of its gradualdevelopmentin connexion and reciprocal

interaction with his composing. That is astonishing,when one considers that it was a

characteristic, indeed a defining characteristic, of Schoenberg'sViennese school that

composingand theorizing went hand in hand with and influencedeach other. Globalalso

means-on the one hand-that these concepts are (more or less) expected by and large to

mean the same regardlessof where they appear; that is, to be freely available. Since

contradictionsariseout of this, they are, on the other, creditedas conceptswith nothingor

everything: ambiguous, imprecise, capable of being arbitrarily combined, subject to

'musicological'interpretation-thus could their statusin today's thinkingabout musicbe

described.Yet things look better in Schoenberg'scase than in Webern's;a few scattered

pieces of preliminarywork exist.4 But the generalstateof knowledge,even with reference

to Schoenberg,is such that it is impossibleto determinewhether the inconsistencieslie in

the concepts themselvesor in Schoenberg'sthinking,or whether they originate from the

fact that in each case the verbalexpressionshave not been examinedwhere they occur,but

have been torn from their context, historical, musical, and of subject-matter.

In any examinationof Webern'stheoreticalutterances,the role thatmightbe playedby

the medium of communication must be taken into consideration-in contrast to

Schoenberg'swritings, publishedor intendedfor publication,andhis publiclectures,or the

publishedessaysandbooks of Rufer,Ratz, or Spinner.Webern'sstatementsmaybe binding

to a different degree, or in a different kind of way. A large proportionof his statements

concerninghis own music is to be foundin his letters, a few in his diaryentries.The notesof

two seriesof lecturesgiven by Webern in 1932and 1933in a privatehouse in Vienna, to an

audience of musiciansand musical laymen, are of central significance.These notes were

taken by a friend of Webern's, the lawyer Ploderer, who contributed to the musical

periodical23-as did Willi Reich, who reportedon these lectures in 23 and in Musik,and

who publishedthem in 1960under the title Der Wegzur neuenMusik.5The printingof the

lecturesin 23 was plannedat the timebut provedimpossible;in anyevent Webernwill have

known about this plan. No doubts have therefore been raised about their subjectively

bindingnature:that Webern expressedhimself in an entirelyconsistentmanner,especially

in mattersof 'terminology',in his letters to Schoenberg,Berg, Reich, HumplikandJone,

Kolisch,and Stein(to mentiononly a few of the most pertinentamongthose thathavebeen

published)is firmly established.Only occasionallydoes the fact that those whom Webern

3Cf. for example Carl Dahlaus, 'Schonbergs musikalischePoetik',

inArchivfurMusikwissenschaft33(1976), pp.81-88.

4For instance, Rudolf Stephan, 'Der musikalische Gedanke bei Schonberg'(The musical idea in

Schoenberg), in

RudolfStephan, lom musikalischenDenken. GesammelteVortrdge,edited by Rainer Damm and Andreas Traub (Mainz,

1985), pp.129-137; also Rudolf Stephan, 'Zum Terminus "Grundgestalt"'(On the term 'Basic Shape'), ibid.,

pp.138-145.

SAnton Webern, Der Weg zur neuenMusik, edited by Willi Reich (Vienna, 1960); English Version The Path to theNew

Music (Bryn Mawr and London, 1963), translated by Leo Black. (The passages appearing in this article have been

translated by Michael Graubart.)

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HORIZONTAL AND VERTICAL

addressedincludedmusicallaymen serve the musicologicalauthors-when they permit(as

they think) Webern, but in reality themselves,a few liberties in mattersof thought. For

Webern, however, who throughouthis life felt himselfindebtedto the ideasof KarlKraus,

the binding natureof his utterances,musicalas well as verbal, was independentof whom

they were addressedto: 'In the end the words after all make the thought'he once wrote to

HildegardJone.

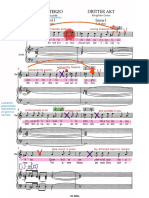

andthe vertical

The title of this essay promised that it would deal with the horizontal

of musicalideas.These are central concepts in Webern's thinkingabout music

presentation

insofar as they are for him the conceptual starting points from which the principal

developmentsof music-history,includingthat of his own time, canbe properlyunderstood

and described.A similarrole is played for Halm by the two 'cultures',fugue and sonata;6

analogousideasunderlieKurth'sbookson Bach, Romanticharmony,andBruckner.It is the

relationshipbetween homophonyand polyphony,between harmonyandcounterpoint(and

the theory of harmonyand the theoryof counterpoint),thathasalwaysdetermined,though

in continuallydifferent ways, the historyof musicandhas always been the subject-matter

of music-historyand musicology. They are central to Webern's thinkingalso becausethe

remainingconcepts, 'traditional'ones and others, group themselvesaroundthem and are

brought into relationshipwith them. They are of central significance,finally, becausea

peculiarityof the conceptualizationof musicalspacethat has developedmainly within the

Schoenbergschool can be attachedto them. This specialmeaningof horizontalandvertical

presentationmay perhapshavebeen observed-I do not know-but in anycaseignored.On

the other hand, these expressions are in common use everywhere. The incalculable

consequencesof this ignoringof their specialmeaningwithin the Schoenbergcircle include

extraordinary,diffuse, inaccurate, and in all manner of ways wrong ideas about what

Webernmight have meantby the synthesisof horizontalandverticalpresentation.Thereis

talk of the identity of the horizontal and the vertical, of the interpenetrationof the

horizontaland the vertical or of their annulment;some authorsobviouslyeven manageto

imagine somethinglike a diagonal.The presentstate of researchinto musicalspace, which

can only be sketchedhere, must at any rate be assessedas not yet scientific. And this not

because 'musical space'-whether this is a philosophicor aesthetic concept or a physical

one-is so difficult to treat, but becausein Webern's and Schoenberg'scase the pieces of

informationthat exist have not yet been takeninto considerationat all; or, to put it even

more polemically:becausethe texts have till now not been readcorrectlyor have onlybeen

read incompletely.

Space

'THE TWO-OR-MORE-DIMENSIONALSPACE IN WHICH MUSICAL IDEAS ARE PRESENTEDIS A

UNIT.' This formulationof the 'law' that is of such importancefor twelve-note music, as

Schoenbergsaid, is to be foundin the essay 'Compositionwith Twelve Tones'.7The text is

basedon extensive drafts,dating fromJanuary1934,for a lecture in Princeton.8There, the

talk is of'the law9 concerningtheunityofmusicalspace'and 'the law9 of the absoluteview10

of musical space';in the version of 1941/50, the statementthat correspondsto this is: 'the

an absoluteandunitaryperception'

(p.223). The relationshipof

unityof musicalspacedemands

Schoenberg'sthinkingin 1934to that of 1941or 1950cannotbe investigatedhere. Among

other aspects, this discussion would have to concern itself with the tendency towards

6Cf. for example August Halm, Von zwei Kulturender Musik (Of two cultures of music) (Munich, 1913, reprinted

Stuttgart, 1947); see also Regina Busch, 'August Halm Uiberdie Konzertform'(August Halm on concerto form), in

Notizbuch 5/6: Musik (Berlin-Vienna 1982), pp.107-153.

71941; first published 1950 in Style andIdea(New York), ed. Dika Newlin; the above quotation, and those following,

are taken from the new edition of Style and Idea (London, 1975), ed. Leonard Stein, where the essay appears as

next

'Composition with Twelve Tones (1)'. (Claudio Spies, in his introduction to the 1934 lecture-notes-see

note-states that the 1941 essay was originally given at UCLA in March 1941 and repeated at the University of

Chicago in May 1946.-M.G.)

8Published in Perspectivesof New Music, Fall-Winter 1974, Vol.13 No.1.

9'Gesetz'. Spies's translation, 'notion' (loc.cit) misses the binding force of Schoenberg's expression.--M.G.

io'Anschauung' ('way of regarding'); Spies's 'conception' does not convey the implication.-M.G.

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TEMPO

general validity that inheres in 'two-or-more-dimensional' or 'absolute and unitary'. In the

present context, we need only hold on to the fact that two components of this

conceptualization of space, namely 'absolute' and 'unitary', were retained. It is not yet

known, unfortunately, how Schoenberg arrived at this law, and when its formulation as a

'law' was definitely established. In the 'Diskussion im Berliner Rundfunk' ('Discussion

broadcast on the Berlin Radio') of March 1931,11Schoenberg refers literally to the law

'established by himself'. It can therefore be assumed that Webern knew of it at the latest by

this time, and had thought about it. And surely he must not only have known this law, but

must have been familiar with Schoenberg's theoretical investigations and plans connected

with it; to what extent, is still to be discovered. At any rate, the concepts 'musical idea',

'comprehensibility', 'coherence', '(musical) logic', 'presentation' entered into his musical

and theoretical thinking (and that of the Schoenberg school in general) and were used as his

own. The majority of these concepts correspond to the working titles of Schoenberg's

theoretical reflections, which centred primarily round the 'musical idea'. The 'law of the

unity of musical space', however, assumed quite exceptional significance for Weber's

musical thought; his thinking orientated itself around this law even after Schoenberg had

already emigrated and postal contact between them had loosened. This was especially the

case when he spoke or wrote about his own music and drew theoretical consequences

towards which Schoenberg had not pointed the way.

The very first series of lectures that Webern gave, The Path to Compositionin Twelve

Notes, January to March 1932, goes back to an outline which Webern wrote for a course in

Mondsee in 1931. He had already occupied himself with this and reported details of his plans

to Schoenberg as far back as 1929. Webern's course was planned as an introduction to some

of Schoenberg's lectures and the idea of discussing it with Schoenberg was an obvious one.12

It was Schoenberg's suggestion that 'only I would recommend your arranging the analyses

possibly in such a way (by the choice of works) as to show the logical development towards

twelve-tone composition'; the title, too, originated with Schoenberg, yet with a variant:

'Composition with 12 Notes'. In his 1932 lectures, Webern continued to speak of

composition in 12 notes. This enabled him to create in his listeners' minds the connexion

with a conception of music into which the new methods of composing could also be

seamlessly incorporated. Thus the 'way' can also be followed thus:

Then I did write a quartetagain thatwas in C major-but only in passing...Schoenberg's

songs,op.14:...Here,too,

we still find a tonality-but no cadence. (Lecture IV)

Schoenberg'sop.1t...No.1: the close is Eb,-it does not close in any key;...In this musicalmaterial,new laws have

asserted themselveswhich have made it impossibleto describe a piece as being in this key or that. (LectureV)

'atonal music' can be more appropriatelydescribedas 'music that is not in a particularkey' (Lecture I)

finally, too:

The chromaticpathhasbegun, i.e. the path that entails stridingforth in semitones.(LectureII, with referenceto

Brahms'sGesangderParzen).13

It is not only important that the formulation 'Composition in Twelve Notes'can be readily

joined onto the above formulations and functions in a suggestive way; it is above all

important that the conception which Webern arouses or addresses by means of these

formulations is a spatial conception. One might say even one with some degree of

concreteness, insofar as this spatial conception enables the 'concrete' musical experience of

music that 'is in C major' to be communicated by analogy. This becomes plain if one reads

the lectures through for the formulations tied to spatial conceptions. It is, of course, true

that our vocabulary, at least as soon as thinking is concerned, is in any case tied to spatial

conceptions; and perhaps music, which is known to have 'a close relationship with time', is

especially affected by the fact that temporal and spatial relationships can only be conceived

and described in dependence (including linguistic dependence) on each other. Weber's

"In Arnold Schoenberg,GesammelteSchriften,edited by Ivan Voytech (Frankfurt, 1976), pp.272-282.

12Cf. Hans and Rosaleen Moldenhauer, Anton von Webern.A Chronicleof his Life and Work, (New York, 1979),

pp.373f. Schoenberg's suggestion in the following sentence is quoted from p.374.

"My translations.-M.G.

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MUSICAL SPACE

mode of speech,however, makesuse of the dependenceon (or relationshipto) spacein that

it raisesinto consciousnessthe musical and spatialexperiences enshrinedin concepts like

'foundation14note', 'returning to the foundation14key' or 'relationshipbecoming ever

looser' as experiences (andnot as facts of nature).As a resultof this, 'suspended15

tonality'

acquiresa positively sensuousquality:

Everything,however, still had a relationshipto a key, aboveall at the end...[abouthis quartet,that 'in passing'was

still 'in C major'].The foundationnote itself, however, was not there-it was suspended15in space, invisible,no

longer necessary. On the contrary; it would already have been disturbing if one had really referred one's

experience to the foundationnote.13

And the idea that the note-row shouldtake over certainof the functionsof the foundation

note is soundedin formulationslike: 'The twelve notes in a quite specificsequenceform the

for the whole composition'(LectureVI), and:composingor inventingis 'founded

foundation

on the row' (Lecture VII).13

in space':that is alreadya different spaceor spatialdomainthanthe one in

'Suspended15

which a piece is situatedif it is 'in a key'. Whetherit is tonalityin generalor a particularkey

that yields the space in a given case cannot be clarified here. But the space in which the

foundationnote referred to is floating15seems to be an altogetherdifferent kind of space

(the meaningis not merely that of 'extended'tonality),a spacenot formedout of tonalities.

The way in which the twelve notes, which now have 'equalrights'and 'haveenteredinto

their dominion'(LecturesIII,V), relateto thisspaceor are locatedin thisspaceis againonly

metaphoricallyexplainedby Webern: 'The row in its originalformandat its originalpitch

gains an analogousrole to that of the "principalkey" of earlier music;the "reprise"will

naturallyreturnto it. We close "in the samekey"!'16(-a quotationfromTheMastersingers,

in which the formulations'in' a key, 'in' twelve notes resonateonce more. Schoenberg,

incidentally,had also quoted the sameplace in similarcontexts:in the chapteron closesand

and at the beginningof the essay 'Problemeder Harmonie'

cadences in the Harmonielehre,

Erwin

of

Stein, in 'Neue Formprinzipien',hadalso alludedto it with

Harmony);

(Problems

'You set the rule yourself and then obey it'.17)At the end of his secondlecture-series,in

April 1933,Webern once more took up the earlier conception:'As earlierone wrote in C

major, so we write in these 48 forms'. Otherwise he generally employed Schoenberg's

'compositionwith twelve notes'. Whether it was Schoenberg'slecture in Vienna at the

beginningof 1933that causedhim to changehis formulation,or he had chosen the version

with 'in' for didacticor similarreasonsin the first lecture-seriesonly, cannotbe determined

at present. Spinner and Reich have assuredme in letters that there was no difference

between 'in' and 'with', or that the differencewas negligible. In our context, however, in

which we are concerned(amongstother things) with changesin spatialconceptions,it is

perhapsuseful to rememberthat at one time both formulationswerein use.

Webern'sexample of the ash-traywhich, from whatever sideit is viewed, remains'the

same' (Lecture VII, 1932)is also of significancefor the conception of space. In the essay

'Neue Formprinzipien', Stein reports that Schoenberg once picked up a hat during a lecture

and turned it 'in all directions': 'Do you see-this is a hat, whether I look at it from above,

from below, from in front, from behind, from the left, from the right; it is and remains a hat,

even if it looks different from above than from below'. Schoenberg always held firmly to

this example with precisely this description: in 'Composition with Twelve Tones (1)'

(1941/50) we have knife, bottle, watch; in the draft for this (1934) watch, bottle, flower.

14German

'Grundton','Grundtonart'.I have chosen 'foundation'in preferenceto the usual'fundamental'because

the latter word has (at least in common usage) lost the literal connotations'ground','earth'(underfoot)and the

derived connotations 'cause', 'reason (for)' of the German 'Grund'-M.G.

15'Suspended

tonality'is Schoenberg'sEnglishphrasefor 'schwebendeTonalitat'. 'Hovering'or 'floating'ismore

exact: '...floating in space...'.-M.G.

16'Wir schliessen im gleichem Ton'.

"7ErwinStein, 'Neue Formprinzipien'(New Principlesof Form) in Musikbldtter

desAnbruch6. Sonderheft:

Arnold

zum 50. Geburtstage,

13. September

1924, pp.286-303,quotationsfrom pp.291 and 295.

Sch'nberg

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TEMPO

That the idea was importantfor him is shownby his 'stage-direction'18

which he notatesin

his script:'(show)'.19It is his attempt to symbolizethe 'law of the absoluteview of musical

space', in which-in the 1934formulation-'there is no absolute upwards,downwards,

forwards or backwards, since every direction becomes a different one from a different

point of that space'.

'Froma different point of that space':thatmeansthat fundamentallyevery pointin this

space is capableof becoming the ideal vantagepoint of the observer,the vantagepoint for

the 'view'; there is no single, predeterminedor fixed pointfromwhich the directionscould

be determinedin a particularcase or to which they could be referred.That which is right,

left, etc., changes with the point occupied in space. 'Absolute', therefore,in the senseof

independent, unrestricted, released from every tie (certainly from the tie to a fixed

referencepoint in space):specifically,not relative.Thisconceptionwas alreadyfamiliarto

the Schoenbergschool in the 1920'sas is shown by the example of Stein, or, too, that of

Greissle(essay on Schoenberg'swind quintet).20It can be conjecturedthat the 'absolute'

conception of space was seen as a contrast to one referred to a foundationnote; the

foundationnote would thenbe a predeterminedreferencepointthatwould remainin force

throughoutthe piece.

What sucha kind of spacewould look like, andhow the objectswithin this spacecould

be recognized and modified-about this, nothing is known. The only thing that is firmly

establishedis that in the Schoenbergianand Weberian space,in place of relationshipto a

foundationnote, the interrelationshipsbetween the notes (the twelve notes relatedonly to

each other, and, further,all the notes that occur) prevail,and 'only the note-relationships

are perceived and compositionally worked out21absolutely'.19'Absolutely' therefore in

particularmeans the independentexistence (independentof the foundationnote) of noterelationships,'absolutely'takenas a quality turnedto some extent into somethingpositive

which belonged, in music referredto a foundationnote, only to the foundationnote or the

'tonic': hence no absoluteupwards,downwards,etc., but absolutenote-relationships.The

space in which music referred to a foundationnote-or a piece referredto a foundation

note-is playedout is not simplya specialcase of the Schoenbergianspace (with a vantage

point fixed for a particularpiece); the spacesare differentin kind. Inversions,retrogrades,

etc., also occur in tonal music, and in this too an identity-relationis contained in their

relationshipto what they invertor revert,and thedifficultybecomesplainerstill in the case

of variationor reprise:in this music, too, the factorsuponwhich identificationor identity

depend, or by which they are influenced,are determinedby very varied conditions.It is

obvious that the concepts of identity and variationmust be consideredanew for musical

events occurringin twelve-note music. Variationin the 'traditional'sense-about which,

indeed, agreement ought also still to be sought-is too close to elementarytwelve-note

procedures;in the twelve-note context what it could encompassis too trivial-something

which at least everyone who has tried to understandWebern's piano variations has

experienced. Guidedby the circumstancesin twelve-note music, we shallhave to modify

the concept; but only modify it, not abolish it.

A further aspect of the 'absoluteness'of Schoenbergianspace must also be discussed.

The description of the 'absolute' in the essay of 1941/50 reads: 'In this space, as in

thereis no absolutedown, no rightor

Swedenborg'sheaven (describedin Balzac'sSeraphita)

left, forward or backward.22 Comparedwith the version of 1934(or, too, that of Stein,

1924), this, therefore, speaks only of 'absolute down', no longer of 'up and down' or

'upwards and downwards'. We are dealing here not with a quotation from Balzac or

"'Vortrags-Anweisung': Regina Busch's pun is untranslateable. The phrase means 'mark of interpretation' in the

musical sense (dynamics, tempo, etc) but 'Vortrag' also means 'lecture'.-M.G.

19Perspectives,Fall-Winter 1974, pp.84-85.

20Felix Greissle, 'Die formalen Grundlagen des Blaserquintetts von Arnold Schbnberg' (The formal foundations of

the Wind Quintet of Arnold Schoenberg), in Musikblatterdes Anbruch 7 (1925), pp.63-68;

especially pp.65-66.

21German

'auskomponiert'-M.G.

22Styleand Idea (1975),p.223.

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MUSICAL SPACE

Swedenborg, but with Schoenberg's synopsis of what Balzac's Seraphita relates of

Swedenborg'steachingin the chapter'The Cloudsin the Holy Place'andthe descriptionof

the 'ascension'of Seraphitawho hadby thenbecome the 'soul'.To what extent Schoenberg

derives his bearingsfrom Balzac/Swedenborgand to what extent more generally from a

'centre-point theory' with antique or Goethean roots23cannot be investigatedhere. If it

shouldreallybe the case that we are dealingwith sucha theory, thenat any rateit conflicts

with the conception, taken-and aptly taken-by Schoenbergfrom Swedenborg/Balzac,

of an ascentfrom centre to centre or from circle to circle into the actualcentre. Forin this

'heaven' there is indeed no absolutedown, but evidently an absoluteup. It can hardlybe

denied that this conflict musthave implicationsfor the conceptionof musicalspace,for the

presentationof ideas within that space, and also for the possible presence of a musical

'centre'.

This problem remains unclarified as much in the case of Webern as in that of

Schoenberg. It will be possible to take as a starting-point the fact that Schoenberg

concerned himself with both (conflicting) conceptions at the outset, i.e. undoubtedly

already at the time he was working on Die Jakobsleiter-towhich, as we know, he was

and Strindberg'sJacobWrestles.In

stimulatedby amongst other things Balzac's Seraphita

Strindberg'sfragment,too, he was able to encounterthe experience, pertinenthere, of the

loss of the familiar sensationsof space and time: the appearanceof the Swedenborgian

'unknownone' causes the normal space-time relationshipsto be put out of action: '...that

the churchseemsto be so distant.It hasrecededby at least a kilometre...HaveI lost my sense

take half an hour to walk along thisbit of the RueBonaparte,

of distance-measurement?...I

which otherwise only takesfive minutes...Iacceleratemy steps,I run,but the unknownone

pursueshis pathwith so exactly correspondingspeedthat I do not succeedin shorteningthe

distance that separates us.24 Schoenberg'sTotentanzder Prinzipien(Death-Danceof the

(written, like the text of Jacob'sLadder,in the middle of January1915)begins

Principles)

a

similarly: peal of bells that does not stop strikingafter the twelfth stroke;a sequenceof

associations: midnight-the blackest-darkest-eternally infinite-unimaginable-'one

sound!Without any differentiation'.After differencesare perceived,first by the sensesof

seeing and hearing, then by the other senses, a stage is reached in which the senses

differentiate too much. Finally the stage of 'recognition'25:

We recognize25that it lives;by its pallorandinsipidity;by its wealth of indistinctnesses;...Bythe fact thatits pallor

and insipidity now resolve themselves into colours and shapes; that is called binding oneself together...it

disintegratesmore andmoreandis in motion...Somuchandevery individualthingseemsimportant...Nowit sings;

each one sings somethingdifferent, thinksthat he sings the same,and really in one directionit soundsin unison26;

(in amazement)in anotherpolyphonic.Ina thirdandfourthit soundsdifferentagain;but thatcannotbe expressed.

Altogether, it has countlessdirections,and every single one can be perceived. (Heightening)And all of themare

lost towardssomewherewhere one could find them. It would be easy to follow them, for now one has the way of

viewing.27

This degree of recognition25is not exceeded furtherin the Totentanz,in contrasttherefore

or Balzac's/Swedenborg'sascension.Thenin the last partof the text almost

withJakobsleiter

'normal'conditions are attained again:

Zur

Webernsund GoethesMethodikder Farbenlehre.

23See, for instance, Angelika Abel, Die Zwolftontechnik

Schule(Webern'stwelve-note techniqueandGoethe'smethodology

derNeuenWiener

undXisthetik

Kompositionstheorie

of colour-theory. On the compositionaltheory and aesthetics of the new Viennese school) (Wiesbaden,1982).

24Translatedby the present translatorfrom the Germantranslationby E. Schering,Inferno.Legenden

(Munich,

1920)-M.G.

25German'Erkenntnis; erkennen': recognition, recognize; cognition, cognize; apprehension, apprehend;

knowledge, know-M.G.

26TheGerman'einstimmig'(lit. 'one-voiced') means'monophonic'(or even 'for one voice') in the musicalsense,

but also carries implicationsof 'joining in together', 'being of one voice (unanimous)',etc.-M.G.

27Texte(Vienna, 1926) p.25 (shortened)-M.G. translation.

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TEMPO

10

(It strikes thirteen.) Thirteen.-Not,

indeed, twelve, but at least a boundary in this emptiness!

As late as 1932, Schoenberg pointed out similar circumstances in his second orchestral song

from op.22, composed at almost exactly the same time (30 November 1914-8 January

1915):

...or, however, one has, as in an aphorism or, too, in the lyric, to invest every smallest component with such a great

richness of relationships to all the other components that the minutest change of position allows as many new

shapes28to be seen as in other contexts does the richest working-out and development. The shapes are then situated

as in a cabinet of mirrors and can continually be seen simultaneously from all sides and display relationships in all

directions.29

The difference from the ideas of Balzac/Swedenborg is not only a matter of the conflict,

mentioned above, between a centre-point conception and one of ascending degrees.

Schoenberg's space is not one in which terrestrial conditions are put out of action or at least

have become irrelevant; it is not described negatively ('no up, no down', etc.), but is a space

with other (than the usual) properties, but quite 'concrete' ones: in one direction it sounds

single-voiced, in another polyphonic-but the directions can evidently be distinguished

from one another. 'Altogether, it has countless directions, and every single one can be

perceived.' Countless: that is not anything uncertain, unlcear, unfocussed-just'countless'.

That for Schoenberg unusual spatial conceptions could be based on, as it were, real

experiences, is shown by his description of Loos's architecture:30

His houses are conceived of in three dimensions from the beginning, instead of being thought of in terms of a series

of planes fronted by a facade. They are so constructed that, with the use of only a few occasional steps, one can

proceed from the first floor to the second without being conscious of the change. Uncle Arnold compares them to

once.

sculptures made of glass, in which one can see all the angles at

Really conceived three-dimensionally, a glass space in which one can see all the angles at

once, or, as in Totentanz, in which it sounds single-voiced in one direction, polyphonic in

another, in which everybody sings something different but believes himself to be singing the

same: these conceptions paraphrase one of the principal properties of Schoenberg's and

Webern's musical space, the one which finally also makes possible the synthesis of the

horizontal and vertical presentations of a musical idea. Schoenberg laid this down in the law

of the unity of musical space; he was conscious of the fact that 'absoluteness'and 'unity'are

closely related.

(To be continued)

28'Gestalten'.

29My translation-M.G.;

Claudio Spies.

see also leaflet in record-set The Music of Arnold Schoenberg,Vol.III (CBS): notes by

Diariesand Recollections1938-1976 (New York, 1980), p.133 (diary entry of 3

30InDika Newlin, SchoenbergRemembered.

November 1939).

RETAIL AND SUBSCRIPTIONS

We regret to announce increases in the retail price of TEMPO magazine and in its subscription rates. Our

only the actual

previous rates had been maintained for three years in the face of steeply rising costs-not

cost of producing the magazine to a consistently high standard, but the effect of successive increases in

the differential

postage, packing, and envelopes. In particular, the old rates no longer accurately reflected

between UK and overseas postage costs. Our new rates, accordingly, will be ?1.20 for single issues,

exclusive of postage; UK subscription ?6.00 pa, overseas subscription ?7.00 pa (both figures inclusive of

TEMPO

postage). We trust that subscribers will appreciate our financial pressures, and still consider that

gives value for their money.

This content downloaded from 156.143.240.16 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 15:21:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Вам также может понравиться

- Tonal Coherence in Prokofiev's MusicДокумент153 страницыTonal Coherence in Prokofiev's Musicjlas333100% (2)

- How Is Extra-Musical Meaning Possible - Music As A Place and Space For Work - T. DeNora (1986)Документ12 страницHow Is Extra-Musical Meaning Possible - Music As A Place and Space For Work - T. DeNora (1986)vladvaidean100% (1)

- Bruce Ellis Benson The Improvisation of Musical Dialogue A Phenomenology of Music 2003Документ216 страницBruce Ellis Benson The Improvisation of Musical Dialogue A Phenomenology of Music 2003abobhenry1100% (2)

- Philosophy of MusicДокумент57 страницPhilosophy of MusicSilvestreBoulez100% (1)

- Various Tunings For Acoustic GuitarДокумент13 страницVarious Tunings For Acoustic GuitarKathryn Johnston100% (2)

- Clarion Register - Alternate Fingering Chart For Boehm-System ClarinetДокумент4 страницыClarion Register - Alternate Fingering Chart For Boehm-System Clarinetshu2uОценок пока нет

- The Heart Asks Pleasure First, The Piano Soundtrack - M. NymanДокумент3 страницыThe Heart Asks Pleasure First, The Piano Soundtrack - M. Nymankrrrt 1974Оценок пока нет

- 20 Physics ExperimentДокумент26 страниц20 Physics ExperimentArjohnReiReodicaОценок пока нет

- Digital Booklet - Greatest Hits (International Itunes Version)Документ4 страницыDigital Booklet - Greatest Hits (International Itunes Version)chayan_mondal29Оценок пока нет

- Thomas Ades at 40 PDFДокумент9 страницThomas Ades at 40 PDFBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Zbikowski 2002-Conceptualizing MusicДокумент377 страницZbikowski 2002-Conceptualizing Musicbbob100% (1)

- Czech Music GuideДокумент76 страницCzech Music GuideDobromira Vaklinova100% (1)

- Kerman, Joseph - Contemplating Music - Challenges To Musicology-Harvard University Press (1985)Документ257 страницKerman, Joseph - Contemplating Music - Challenges To Musicology-Harvard University Press (1985)Imri Talgam100% (1)

- Becker. Is Western Art Music Superior PDFДокумент20 страницBecker. Is Western Art Music Superior PDFKevin ZhangОценок пока нет

- Lessons in Music Form A Manual of Analysis of All the Structural Factors and Designs Employed in Musical CompositionОт EverandLessons in Music Form A Manual of Analysis of All the Structural Factors and Designs Employed in Musical CompositionРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Wittgenstein On Understanding Music - Yael KaduriДокумент10 страницWittgenstein On Understanding Music - Yael Kadurimykhos100% (1)

- Twelve-Tone Serialism - Exploring The Works of Anton WebernДокумент21 страницаTwelve-Tone Serialism - Exploring The Works of Anton WebernAndréDamião100% (1)

- On The Imagination of ToneДокумент38 страницOn The Imagination of ToneVincenzo Zingaro100% (1)

- University of California Press American Musicological SocietyДокумент22 страницыUniversity of California Press American Musicological Societykonga12345100% (1)

- Boynton-Some Remarks On Anton Webern's Variations, Op (2009)Документ21 страницаBoynton-Some Remarks On Anton Webern's Variations, Op (2009)BrianMoseley100% (1)

- Burkholder - Borrowing As A FieldДокумент21 страницаBurkholder - Borrowing As A FieldDimitris Chrisanthakopoulos100% (1)

- WINTLE Analysis and Performance Webern S Concerto Op 24 II PDFДокумент28 страницWINTLE Analysis and Performance Webern S Concerto Op 24 II PDFleonunes80100% (1)

- Conley, Cartographic CinemaДокумент23 страницыConley, Cartographic CinemaBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- IntermedialityДокумент22 страницыIntermedialitymagdalinintalОценок пока нет

- Stravinsky: AdornoДокумент43 страницыStravinsky: AdornoHéloïseОценок пока нет

- Agawu Kofi - Review de Cook Music Imagination An CultureДокумент9 страницAgawu Kofi - Review de Cook Music Imagination An CultureDaniel Mendes100% (2)

- Japan Living - Form and Function in The Cutting EdgeДокумент257 страницJapan Living - Form and Function in The Cutting EdgeGércio Chaibande100% (2)

- Michel CHION-Guide of Sound ObjectsДокумент212 страницMichel CHION-Guide of Sound Objectsdong_liangОценок пока нет

- Kerman. A Few Canonic VariationsДокумент20 страницKerman. A Few Canonic VariationsClases GuitarraycomposicionОценок пока нет

- Foundations of Musical Aesthetics McEwenДокумент140 страницFoundations of Musical Aesthetics McEwenmaridu44100% (2)

- The Classical Cadence: Conceptions and MisconceptionsДокумент68 страницThe Classical Cadence: Conceptions and MisconceptionsPhilipp SobeckiОценок пока нет

- Butt 4Документ15 страницButt 4Scott DonianОценок пока нет

- Motion and Feeling Through Music Keil PDFДокумент14 страницMotion and Feeling Through Music Keil PDFRobert SabinОценок пока нет

- Musical Beauty: Negotiating the Boundary between Subject and ObjectОт EverandMusical Beauty: Negotiating the Boundary between Subject and ObjectОценок пока нет

- Moseley, Transformation Chains, Associative Areas, and A Principle of FOrmДокумент26 страницMoseley, Transformation Chains, Associative Areas, and A Principle of FOrmBrianMoseley100% (1)

- Technical Bases of NineteenthДокумент266 страницTechnical Bases of NineteenthBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Beethoven and RomanticismДокумент14 страницBeethoven and RomanticismAndrew BowieОценок пока нет

- COOK - Music Theory and 'Good Comparison' - A Viennese PerspectiveДокумент26 страницCOOK - Music Theory and 'Good Comparison' - A Viennese PerspectivejamersonfariasОценок пока нет

- Caplin 2004Документ68 страницCaplin 2004Riefentristan100% (1)

- Taruskin - On Letting The Music Speak For Itself - Some Reflections On Musicology and PerformanceДокумент13 страницTaruskin - On Letting The Music Speak For Itself - Some Reflections On Musicology and PerformanceLaís RomanОценок пока нет

- Cox - 8 Etudes NM9 - 04cox - 051-074Документ24 страницыCox - 8 Etudes NM9 - 04cox - 051-074Garrison GerardОценок пока нет

- Cox - 8 Etudes NM9 - 04cox - 051-074Документ24 страницыCox - 8 Etudes NM9 - 04cox - 051-074Garrison GerardОценок пока нет

- The University of Chicago Press Critical InquiryДокумент20 страницThe University of Chicago Press Critical InquiryAna Alfonsina MoraОценок пока нет

- Taruskin - On Letting The The Music SpeakДокумент13 страницTaruskin - On Letting The The Music SpeakDimitris ChrisanthakopoulosОценок пока нет

- Pousseur and Clements - Stravinsky by Way of Webern IДокумент40 страницPousseur and Clements - Stravinsky by Way of Webern IIliya Gramatikoff100% (1)

- Mzsteri of Varese PDFДокумент3 страницыMzsteri of Varese PDFOlivera DjuricicОценок пока нет

- Zbikowski 2002-Conceptualizing Music IntroductionДокумент17 страницZbikowski 2002-Conceptualizing Music IntroductionbbobОценок пока нет

- 10 2307@1343107 PDFДокумент13 страниц10 2307@1343107 PDFSofi GarellaОценок пока нет

- After-Thoughts (Tristan Murail)Документ4 страницыAfter-Thoughts (Tristan Murail)Jose ArchboldОценок пока нет

- Filozofia-Hudby NGDДокумент61 страницаFilozofia-Hudby NGDTímea HvozdíkováОценок пока нет

- Musical InfluenceДокумент71 страницаMusical InfluenceAnastasia PekiОценок пока нет

- Deleuze Michael GallopeДокумент38 страницDeleuze Michael GallopeEduardo CampolinaОценок пока нет

- Taruskin 82 - On Letting The Music Speak For Itself Some Reflections On Musicology and PerformanceДокумент13 страницTaruskin 82 - On Letting The Music Speak For Itself Some Reflections On Musicology and PerformanceRodrigo BalaguerОценок пока нет

- Oxford University Press The Musical QuarterlyДокумент12 страницOxford University Press The Musical QuarterlyMeriç EsenОценок пока нет

- Musical Times Publications LTDДокумент6 страницMusical Times Publications LTDРадош М.Оценок пока нет

- What Is Musicology?: Professor Nicholas CookДокумент5 страницWhat Is Musicology?: Professor Nicholas CookJacob AguadoОценок пока нет

- Cage PDFДокумент2 страницыCage PDFRai Sánchez SorianoОценок пока нет

- Oxford University Press The Musical Quarterly: This Content Downloaded From 89.152.6.221 On Sun, 21 Jan 2018 23:28:26 UTCДокумент12 страницOxford University Press The Musical Quarterly: This Content Downloaded From 89.152.6.221 On Sun, 21 Jan 2018 23:28:26 UTCTiago Sousa100% (1)

- Dilemmas, Dichotomies and Definitions:: Acousmatic Music and Its Precarious Situation in The ArtsДокумент13 страницDilemmas, Dichotomies and Definitions:: Acousmatic Music and Its Precarious Situation in The ArtsMatthias StrassmüllerОценок пока нет

- 02 - 832742 - Letter To MKДокумент7 страниц02 - 832742 - Letter To MKJefferson PereiraОценок пока нет

- PDFДокумент33 страницыPDFGerald Paul FelongcoОценок пока нет

- 01 Preface, Introduction, Index 5Документ10 страниц01 Preface, Introduction, Index 5jliimataОценок пока нет

- Lester HeighteningLevelsДокумент49 страницLester HeighteningLevelsThomasSchmittОценок пока нет

- Church Music Research PaperДокумент6 страницChurch Music Research Paperixevojrif100% (2)

- The Performer's Point of ViewДокумент11 страницThe Performer's Point of ViewIreneОценок пока нет

- Carlos Vega-Mesomusic. An Essay On The Music of The Masses (1965)Документ18 страницCarlos Vega-Mesomusic. An Essay On The Music of The Masses (1965)ruizroca100% (1)

- A Cross-Cultural Approach To Metro-Rhythmic PatternsДокумент14 страницA Cross-Cultural Approach To Metro-Rhythmic PatternsMarko PejoskiОценок пока нет

- Experimental Performance Practices: Navigating Beethoven Through Artistic ResearchДокумент24 страницыExperimental Performance Practices: Navigating Beethoven Through Artistic ResearchDimitri MilleriОценок пока нет

- Society For Music TheoryДокумент19 страницSociety For Music Theorycomposerg100% (1)

- Three Music-Theory LessonsДокумент45 страницThree Music-Theory LessonsJohan Maximus100% (1)

- MUS 629 ScheduleДокумент2 страницыMUS 629 ScheduleBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Covach, Form in Rock PDFДокумент12 страницCovach, Form in Rock PDFBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- MUS 629 SyllabusДокумент3 страницыMUS 629 SyllabusBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Mus 211 - Written Theory ScheduleДокумент1 страницаMus 211 - Written Theory ScheduleBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Maus Masculine Discourse OrigДокумент31 страницаMaus Masculine Discourse OrigBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- MUS-629 Course Syllabus PDFДокумент6 страницMUS-629 Course Syllabus PDFBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Mus 211 - SyllabusДокумент3 страницыMus 211 - SyllabusBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Mus 211 - Aural Skills ScheduleДокумент2 страницыMus 211 - Aural Skills ScheduleBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Pitch Structures Class Notes PDFДокумент16 страницPitch Structures Class Notes PDFBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Personal Graph-Mozart, No. 14 TerzettoДокумент1 страницаPersonal Graph-Mozart, No. 14 TerzettoBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Elements of Serialism in The Music of Thomas AdèsДокумент2 страницыElements of Serialism in The Music of Thomas AdèsBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Maxwell, Tracing A Lineage of The Mazurka Genre, Influences of Chopin and Symonowski On Thomas Ades Mazurkas For Piano PDFДокумент169 страницMaxwell, Tracing A Lineage of The Mazurka Genre, Influences of Chopin and Symonowski On Thomas Ades Mazurkas For Piano PDFBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Pitch Structures Class Notes PDFДокумент16 страницPitch Structures Class Notes PDFBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Osu 1217299779Документ186 страницOsu 1217299779BrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Signification of Parody and The Grotesque in György Ligeti's Le Grand MacabreДокумент31 страницаSignification of Parody and The Grotesque in György Ligeti's Le Grand MacabreBrianMoseley100% (1)

- Harrison - 2000 - A Story, An Apologia and A SurveyДокумент10 страницHarrison - 2000 - A Story, An Apologia and A SurveyBrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Vogler, Analysis of PreludeNo. 8Документ16 страницVogler, Analysis of PreludeNo. 8BrianMoseley100% (1)

- Alegant-A Picture Is Worth A Thousand Words-Road Maps As Analytical Tools (2013)Документ15 страницAlegant-A Picture Is Worth A Thousand Words-Road Maps As Analytical Tools (2013)BrianMoseley100% (1)

- Krumhansl - 1995 - Music Psychology and Music Theory Problems and Pr2Документ29 страницKrumhansl - 1995 - Music Psychology and Music Theory Problems and Pr2BrianMoseley100% (1)

- Hook-Cross-Type Transformations and The Path Consistency Condition (2007)Документ41 страницаHook-Cross-Type Transformations and The Path Consistency Condition (2007)BrianMoseley100% (1)

- Composition With A Single Row FormДокумент48 страницComposition With A Single Row FormBrianMoseley100% (2)

- Babbitt-Twelve-Tone Invariants As Compositional Determinants (1960)Документ15 страницBabbitt-Twelve-Tone Invariants As Compositional Determinants (1960)BrianMoseleyОценок пока нет

- Koivisto - 1997 - The Defining Moment The Thema As Relational NexusДокумент41 страницаKoivisto - 1997 - The Defining Moment The Thema As Relational NexusBrianMoseley100% (1)

- Busch-On The Horizontal and Vertical Presentation of Musical Ideas and On Musical (1985)Документ10 страницBusch-On The Horizontal and Vertical Presentation of Musical Ideas and On Musical (1985)BrianMoseley100% (1)

- Ahmet KayaДокумент10 страницAhmet Kayamehmetbarisugur486Оценок пока нет

- Team Pride CheersДокумент9 страницTeam Pride CheersMay PaviaОценок пока нет

- Verbos en InglesДокумент8 страницVerbos en Inglesramirex_umsaОценок пока нет

- O Come Little Children One VerseДокумент1 страницаO Come Little Children One VerseGerr McGregorОценок пока нет

- Detailed Lesson Plan in ENGLISH Grade 9: (Quarter 1 - S.Y. 2020-2021) Week 6Документ7 страницDetailed Lesson Plan in ENGLISH Grade 9: (Quarter 1 - S.Y. 2020-2021) Week 6Daniel Gatdula FabianОценок пока нет

- Fundamentals of Music TheoryДокумент135 страницFundamentals of Music Theoryrudy bОценок пока нет

- Cannes 2015 Day OneДокумент111 страницCannes 2015 Day OneThe Hollywood ReporterОценок пока нет

- English-Singular To PluralДокумент4 страницыEnglish-Singular To PluralIslahIs LahОценок пока нет

- Adonay Rodolfo Aicardi y Los HispanosДокумент12 страницAdonay Rodolfo Aicardi y Los Hispanosjuan esteban baena arbelaezОценок пока нет

- Airlab Brochure 2013Документ4 страницыAirlab Brochure 2013Adrián López MontesОценок пока нет

- HitsДокумент3 страницыHitsBabu BalaramanОценок пока нет

- We Want The Airwaves Guitar TabДокумент5 страницWe Want The Airwaves Guitar TabRodolfo GuglielmoОценок пока нет

- The Foggy Morn 4 ViolasДокумент5 страницThe Foggy Morn 4 Violasame fotosОценок пока нет

- Byzantine Architecture Is The Architecture of The Byzantine EmpireДокумент8 страницByzantine Architecture Is The Architecture of The Byzantine EmpireHitesh SorathiaОценок пока нет

- The Blues Brothers Medley: Alto 2Документ4 страницыThe Blues Brothers Medley: Alto 2DanilОценок пока нет

- Eleanor Rigby GTR MelodyДокумент4 страницыEleanor Rigby GTR MelodyMarcus AbramzikОценок пока нет

- Minor Third - WikipediaДокумент3 страницыMinor Third - WikipediaDiana GhiusОценок пока нет

- Ode To EveningДокумент10 страницOde To EveningÅmîť MâńďáľОценок пока нет

- Jaar InterviewДокумент2 страницыJaar InterviewjoseОценок пока нет

- ALL OF ME - John LegendДокумент3 страницыALL OF ME - John LegendPau SanllehíОценок пока нет

- Drum RubricДокумент1 страницаDrum Rubricgretchen torreyОценок пока нет

- Solitudini Amiche... Zeffiretti... Ei StessoДокумент10 страницSolitudini Amiche... Zeffiretti... Ei StessoRaymondte NovemberОценок пока нет

- Chai Tapri - Office Ke Saamne Set Up Harish - Dinesh Sonu - PawanДокумент8 страницChai Tapri - Office Ke Saamne Set Up Harish - Dinesh Sonu - PawanBibhanshu RaiОценок пока нет