Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

High Birth Rates Growth PDF

Загружено:

FungoОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

High Birth Rates Growth PDF

Загружено:

FungoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

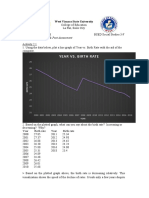

Do High Birth Rates Hamper Economic Growth?

Author(s): Hongbin Li and Junsen Zhang

Source: The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 89, No. 1 (Feb., 2007), pp. 110-117

Published by: The MIT Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40043078 .

Accessed: 19/02/2015 18:36

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Review of

Economics and Statistics.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Thu, 19 Feb 2015 18:36:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DO HIGH BIRTH RATES HAMPER ECONOMIC GROWTH?

HongbinLi and JunsenZhang*

- This paperexaminesthe impactof the birthrateon economic

Abstract

growthby using a panel data set of 28 provincesin China over twenty

years.Because China's one-childpolicyappliedonlyto theHan Chinese

but notto minorities,

thisunique affirmative

policy allows us to use the

variable to

proportionof minoritiesin a provinceas an instrumental

the causal effectof the birthrateon economic growth.We find

identify

thatthebirthratehas a negativeimpacton economicgrowth.The finding

notonlysupportstheview of Malthus,butalso suggeststhatChina's birth

controlpolicyis indeedgrowthenhancing.

statedin a morerecentsurveypaperby Temple(1999), the

has done littleto modifythe

newempiricalgrowthliterature

conclusionsmade by Kelley.

in

The lack of a conclusionis in partdue to thedifficulty

or

birth

rate

a causal effectof populationgrowth

identifying

on economic growth.A simple growthregressioncannot

provecausalitybecause populationgrowthor birthratein

thegrowthregressionmightbe endogenous.One sourceof

or the feedbackeffect.EcoI.

Introduction

endogeneityis simultaneity

nomicgrowthcan affectfertility

becausewithmoreincome,

betweenpopulation

andeconomicgrowth

relationship

parentalhumancapitalimprovesand thusraisesthereturn

has been subjectto debateforhundredsof years.1The to investment

in the humancapital of childrenrelativeto

mostinfluential

schoolof thought,

or theMalthusianschool, investmentin the numberof children

(Becker & Lewis,

assertsthatgivenlimitedresources,

populationgrowthham- 1973).

in boththe

this

sort

is

well

discussed

of

Endogeneity

pers economicgrowth.The otherschool, called the neo- theoreticalliterature,such as Barro and Becker

(1989),

Boserupianschoolof thought

(Boserup,1981),is moreopti- Becker,

and Tamura (1990), and the empirical

Murphy,

mistic.It arguesthatpopulation

thatis

mayhavea scale effect

such as Wang,Yip, and Scotese (1994). Fertility

literature,

beneficialto economicgrowth.2

Moreover,it challengesthe could be

endogenouseven in the absence of the human

Malthusian

modelfortreating

technological

progressas exogeffect.

For example,Galor and Weil (1996) show

capital

enous.Once technological

progressis allowedto be endog- thatwith

therealwage of womenrises,whichleads

growth,

enouslyderivedin themodel,theroleof populationon eco- to lower

fertility.

Endogeneityof thissortcannotbe solved

nomicgrowth

becomesneutral

orevenpositive(Romer,1986,

the lagged populationgrowthor birthrate as

by

using

1990;Jones,1999).

variablessinceparentsareforward

lookingand

debate,thereis stilla independent

Despitethevoluminoustheoretical

into

account

when

take

making

may

growth

prospects

relativelysmall body of well-testedpropositionsabout the

such

as

if

relevant

decisions.

variables,

Moreover,

fertility

impact of populationgrowthor birthrate on economic

in

are

correa

that

the

extent

of

society,

entrepreneurship

growth.A numberof earlyempiricalstudies,such as Coale

lated with both GDP growthand populationgrowthare

(1986), Hazledine and Moreland (1977), and McNicoll

will be subjectto omittedvariables

theregressions

omitted,

(1984), and severalrecentstudies,includingBarlow(1994),

In general,it is

the

second

source

of endogeneity.

or

bias,

Branderand Dowrick (1994), and Kelley and Schmidt

the

difficult

to

solve

endogeneityproblem with crossbetweenthetwo

(1994, 1995), finda negativerelationship

it

is

hardto produceany variablethat

data

because

variables.However,the majorityof theempiricalanalyses country

an

instrument

can

serve

as

(Mankiw,Romer,and

identifying

cannotprovea negativecausal effectof populationgrowth

or birthrateon economicgrowth(Simon, 1989). A more Weil, 1992; Temple,1999).

accuratestatement

of thedebate,whichis in theinfluential In thispaper,we examinetheimpactof thebirthrateon

data from

surveyby Kelley (1988), is thatthereis no definiteconclu- economicgrowthby drawingon provincial-level

the

can

avoid

China.

data

from

one

sion fromthebodyof empiricaltests.Althoughtherewas a

complicountry

Using

of data.3More imporin the 1990s,mostof it cationof international

comparability

surgeof empiricalgrowthliterature

theuniquepopulationcontrolpolicyin Chinaallows

is reticentabout the effectof populationexcept in using tantly,

thecausal effectof thebirthrateon economic

populationgrowthor birthrate as a controlvariable.As us to identify

variableestimation.

growthby usinginstrumental

China startedits one-childpolicy in 1979.4Underthis

Received forpublicationApril6, 2004. RevisionacceptedforpublicationJanuary10, 2006.

policy, each familyis allowed only one child, and the

*

HongbinLi is assistantprofessorand JunsenZhang is professorof

economicsin theDepartment

of Economicsand theInstitute

of Economics, The Chinese Universityof Hong Kong, Shatin,N.T., Hong Kong.

We are gratefulto TerenceChong, JamesKung, Qinglai Meng, Dani

Rodrik,and two anonymousrefereesforveryhelpfulcomments.We also

thankKit Yin Chun for excellentresearchassistance.The authorsacknowledgefinancialsupportsfromtheNationalNaturalScience Foundationof China (No. 70233003), theChineseUniversity

of Hong Kong,and

the International

Centerforthe Studyof East Asian Development.

1The debatestartedafterMalthus

publishedhis famousbook An Essay

on thePrincipleof Populationin 1798.

2 See also Simon (1975),

Pingali and Binswanger(1987), Hayami and

Ruttan(1987), and Kremer(1993).

3 This issue has been raised

by manyauthors,includingRomer(1989)

and Barro(1991).

4 When

Deng Xiaoping gained power in 1978, he startedChina's

economic reform,which,since then,has led to fastgrowth.An equally

important

change,thatof thepopulationpolicy,startedat almostthesame

time. Deng Xiaoping and his colleagues had views similarto the neoMalthusianschool. In discussionsof populationissues, China's policymakersand scholarsalways referto the limitedavailabilityof land and

othernaturalresources,and thatoutputfromland will inevitablyincrease

by less thanthe increaseof labor.Based on thislogic, China startedits

unique one-child-per-family

policy in 1979.

TheReviewofEconomicsand Statistics,

2007, 89(1): 110-117

February

and Fellowsof HarvardCollegeand theMassachusetts

Institute

of Technology

2007 by thePresident

This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Thu, 19 Feb 2015 18:36:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DO HIGH BIRTH RATES HAMPER ECONOMIC GROWTH?

Ill

birthsarepenalized.5The one-child- percentagepointsin a year.Our estimationalso indicates

secondor higher-parity

was initiallyappliedonlyto the thatthesame amountof declineof thebirthratewouldraise

however,

policy,

per-family

Han Chinese,and by way of affirmative

policies,all ethnic the steady-stateper capita GDP by 14.3%. The findings

minoritiesin China were allowed to have two or more suggestthatthe dramaticpopulationcontrolpolicy implechildrenuntilthe end of the 1980s (Anderson& Silver, mentedin China since the late 1970s may indeed have

1995; Hardee-Cleaveland& Banister,1988; Park & Han, helpedthegrowthof theChineseeconomy.9

The restof thepaperis structured

as follows.In section

1990; Peng, 1996; Qian, 1997).6 In some provinces,like

we

the

there

is

no

restriction

on

the

number

of

children

II,

specify

Tibet,

empiricalstrategy.In section III, we

per

introduce

the

In sectionIV, we presentour empirdata

set.

family(Deng, 1995).7

ical

results.

V

Section

concludesthestudy.

allows

This unique affirmative

us

to

use

the

policy

in

a

of

minorities

as

an

instrumental

province

proportion

variable (IV) to identifythe effectof the birthrate on

II.

EmpiricalStrategy

of minorities

economicgrowth.The proportion

is a good IV

forthefollowingtworeasons.First,theprovincialbirthrate

We followtherecentempiricalgrowthliterature

in specof mi- ifyingregression

shouldbe positivelycorrelatedwiththe proportion

equationsfromthesteadystateofa growth

noritypopulationin a provincebecause of the affirmativemodel (see forexample,Mankiwet al., 1992 and Barro&

birthcontrolpolicy.8Second, if we controlfornecessary Sala-i-Martin,

1995). Since we studyprovincesofa country,

of themodelis essentiallyan openeconomygrowthmodellike

variablesthatmaybe correlatedwithboththeproportion

minoritiesand economic growth,such as investment

and thatin Shioji (2001). Specifically,

thegrowthregressionis

of minoritiesshouldbe un- specifiedas follows:

education,thentheproportion

and should not

correlatedwithany omitteddeterminants,

have a directeffecton economicgrowthexceptthrough

the

log(^/^_,) = 7ilog^-i + 72^ + *,7a +

(1)

birthrate.

The regression

resultssupporttheneo-Malthusian

school. where

is thegrowthrateof real percapitaGDP

\og(yjyt-x)

Our GMM estimationsthat controlfor provincialfixed fromtimet - 1 to time

t,logy,-!is thelog ofrealpercapita

show thatthebirthratehas GDP

effectsand correctsimultaneity

laggedforone period,BRtis thebirthratein timef,Xt

a largenegativeeffecton economicgrowth.This findingis are othervariablesthatdeterminethe

steadystate,and 7s

robusteven if we controlforotherdemographicand insti- and e are coefficientsand the errorterm.

Accordingto

tutionalvariables that could be correlatedwith growth. Levine and Renelt

(1992), althougheach paper in the

a declineof thebirthrateby

Accordingto our estimation,

set of rightempiricalgrowthliteratureuses a different

1/1000 will increase the economic growthrate by 0.9 hand-sidevariables,most

papershavefourvariables,thatis,

the initiallevel of real per capita GDP, the birthrate,the

5 To

are given investment

implementthe birthcontrolpolicies, local governments

share(investment

as a percentageof GDP), and

incentivecontracts.These incentivestake the formof fiscalrewardsfor

the

school

enrollment

rate. Besides these varisecondary

and heavypenaltiesforfallingshortof them(Short

birthtargets,

fulfilling

and Zhai, 1998). Moreover,governmentofficialsmay be demotedfor ables, we also followthe literature

and have a numberof

whichmeans

allowingtoo manyabove-quotabirthsin theircommunity,

and institutional

variablesin X.10

demographic

thattheywill lose all futureincome and otherbenefitsassociated with

Following Brander and Dowrick (1994) and Islam

government

positions.

6 In

April 1984, fiveyears afterthe one-childpolicy had been imple- (1995), we estimatethegrowth

regressionin a panelframeforthefirsttimestatedthat work. We divide the total

mentedfortheHan, theChinese government

1978-1998, into four

period,

thereshouldalso be birthcontrolpolicies forminorities,

butthepolicies

intervals.

The

side

variablesare either

five-year

right-hand

should be less restrictive

(Hardee-Cleaveland& Banister,1988). More

only ethnicgroupswitha populationlargerthan 10 million initiallevels or averages over the five-yearinterval.For

specifically,

are subjectto the same policy as theHan, and smallerethnicgroupsare

example,in theperiodof 1978-1983,realpercapitaGDP is

allowed to have second and thirdchildren.However,this birthcontrol

at the 1978 level; the birthrate, the secondaryschool

policyonlyapplies to two largeethnicgroups,Zhuangand Manchu,and

enrollmentrate,the investmentshare,the growthrate of

untiltheend of the 1980s (Deng, 1995).

was notstrictly

implemented

7 Tibetis

droppedfromthe laterempiricalworkbecause data forTibet labor forceshare,and the dependencyratioare five-year

has specificpolicies forit.

are notcompleteand thecentralgovernment

8 China has 55 ethnic minoritieswho live in different

parts of the averages.

and Temple(2001) and Shioji

Accordingto the2000 census,theHan accountedfor9 1.59% of

FollowingBond, Hoeffler,

country.

thetotalpopulationin China.The threelargestethnicgroupsin China are

(2001), we employ the generalizedmethodof moments

Zhuang,Manchu,and Hui, whichhave a populationof 16.2 million,11.0

million,and 9.8 million,respectively.Zhuang mainlylive in Guangxi,

Yunnan,and Guangdong;Manchu can be found in Liaoning, Hebei,

Heilongjiang,Jilin,Inner Mongolia, and Beijing; and Hui are widely

in 19 provincesin China. Amongall theprovinces,Tibet has

distributed

the largestproportionof minoritypopulation;according to the 2000

census, up to 93.89% of its populationis minority.

Qinghai ranksthe

second,with59.43% of its populationas minoritiesin 2000. Jiangxiand

Shanxi have the smallestproportionsof minoritypopulation,both of

whichare lowerthan0.3%.

9 This statement

is purelypositive,whichhas ignoredotherpositiveor

negativeaspectsof forcedbirthcontrolpolicies.We do notintendto make

any normative

judgmentabout China's birthcontrolpolicies.

10Besides the birthrate,

migrationand populationstructures

may also

affectgrowth.Thus,we will use thein-migration

rate,thegrowthof labor

forceshare,and thedependencyratioto testand controlfortheireffects

(theage-dependency

effect)on growth.See Bloom andWilliamson(1998)

and Kelley and Schmidt(2005) formoredetailedarguments.

This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Thu, 19 Feb 2015 18:36:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

112

THE REVIEW OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS

III.

Data

forthegrowthregressions.11

The firststep

(GMM) estimator

of the GMM methodis to take the firstdifference

of the

We employ provincial-leveldata fromChina for the

growthequationin orderto eliminatethe fixedeffects.IV

test.As arguedabove,theChinesedataareunique

empirical

estimationsare thenapplied to the firstdifferences.

The

because China's affirmative

populationpolicy providesa

GMM estimator

cannotonlydeal withomittedvariablebias

debate.

fortestingthepopulation-growth

naturalexperiment

and theendogenousbirthrateas raisedin theintroduction,

data fromone countrycan also avoid theinconEmploying

butcan also deal withtheendogeneityassociatedwiththe

aresubjectto.

ofdatathatcross-country

regressions

firstdifferenceof lagged per capita GDP. Essentially, sistency

In

variables

not

be

data,

consistently

may

cross-country

logyt-1 log,_2is correlatedwiththeerrorterme, e,_i, definedacross countriesbecause different

countrieshave

and is thusan endogenousvariablein the first-differenced

different

statisticalmethods(Barro, 1991; Romer,1989).

equation.

fromone countrycan avoid thisproblem,to a

data

Using

There are two GMM approaches:the first-differenced

defined

because themeasuresare consistently

extent,

GMM (DIF-GMM) approachand thesystemGMM (SYS- large

across provinces.Chineseprovincesare also largeenough

to apply

GMM) approach.Caselli et al. (1996) werethefirst

for the purposeof this studywith an average provincial

theDIF-GMM approachin estimating

a growthregression.

of 33 million,whichis largerthanthepopulation

In the DIF-GMM estimation,

to begin with,one takes the population

of mostcountriesin theworld.

firstdifference

of thegrowthequationin orderto eliminate

The data set consists of demographicand economic

theprovincialfixedeffect.GMM is thenappliedto thefirst

variables of 28 Chinese provincesfor the period 1978difference

withthefirstdifference

of laggedpercapitaGDP

1998.14Demographicvariablescome fromtheBasic Data

instrumented

1

t(logy

logyt-2)

by the past levels of per

ofChina'sPopulation(SSB, 1994) and variousissuesofthe

capita GDP, which,in our case, are logyt-2,logjr_3,and China StatisticalYearbooks

(SSB, 1980-1999). Economic

logyt-4ifthelags exist.Bond et al. (2001) and Bond (2002) variablesare collectedfromthebook of the

Comprehensive

arguethatDIF-GMM could be subjectto the weak instru- StatisticalData and Materials on 50 Years New China

of

mentand finitesamplebiases. To deal withtheseproblems,

(SSB, 1999) as well as the China StatisticalYearbooks

theyuse an SYS-GMM estimator,

developedby Arellano (SSB, 1980-1999). Real per capita GDP is measuredat

and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998), which constant

of

(1952) price.Table 1 reportssummarystatistics

The SYS- variables.

may have superiorfinitesample properties.12

GMM estimator

combinesequationsof thefirstdifferences The data show thatChina's

provincesachieved a very

instrumented

by lagged levels, with an additionalset of highgrowthratein thesampleperiodand at thesame time

equationsin levels instrumented

by laggedfirstdifferences. kept the populationgrowthrate and birthrate low. The

Since theSYS-GMM estimatormaybe superior,we use it annual

growthrateof therealpercapitaincomewas as high

as our main estimator.

We also reportresultsof the DIF- as 8.1% between 1978 and 1998. The annual

population

GMM forcomparison.

growthratewas a low 1.4% and the birthratewas lower

In thispaper,we use theaffirmative

birthcontrolpolicy than2%.15The data also showa considerable

heterogeneity

as theidentifying

instrument

forthebirthrate.In particular, in botheconomic

Guangdongexperigrowthand fertility.

we use theproportion

of minority

populationin a province enced themostrapidgrowthin theperiod1978-1983 with

as the IV As discussedabove, althoughthe Han Chinese an annual

growthrateof 14.6%, while the lowestgrowth

have been subjectto the one-childpolicy,minoritieshave rateof0.3% was inAnhuifrom1983-1988.

Ningxiahadthe

been allowed to have morethanone childeven up to now.

highestbirthrateof 2.8% in theperiod 1978-1983, while

thebirthratein a provinceshouldincreasewith

Therefore,

Shanghaiachieveda birthrateas low as 0.6% in theperiod

the proportionof its minoritypopulation.13

On the other 1993-1998. The

populationis

averageshareof theminority

hand, if we controlfor necessaryvariables thatmay be 10.7% witha standarddeviationof 15.7.

correlatedwithboththe proportion

of minoritiesand ecoTo serve as a good IV for the birthrate in the firstnomicgrowth,such as investment

and education,the pro- difference

of minority

theproportion

estimation,

population

portionof minoritiesshould have no partial effecton needsto have enoughvariationovertime.In orderto check

growth,and shouldnotbe correlatedwithunobservedfac- this,we examinecarefullythe firstdifference

of thisvaritorsthataffectgrowth.

of

the

or

the

able,

minorityproportionover the

change

On

average, the five-yeardifferenceis

five-yearperiod.

11See also Arellano and Bond (1991), Caselli,

Esquivel, and Lefort aboutfiveoutof a thousandforthewholesample.Although

and Blundell and Bond

for more details of the GMM

(1996),

(2000)

method.

12Note thatrelativeto DIF-GMM, SYS-GMM

requiresan additional

assumption,relatedto the initialconditions.See Bond et al. (2001) for

detaileddiscussion.

13Since the one-child

policy startedto apply to two minoritygroups,

Zhuang and Manchu in the 1990s, we exclude them fromthe total

minority

populationforyearsin the 1990s.

14The

startingdata set consistsof 31 provincesin China,but we drop

threeprovinces:Tibet,Hainan, and Chongqing.Hainan and Chongqing

are omittedbecause theywere separatedfromGuangdongand Sichuan,

in the 1990s.

respectively,

15Note thatwe followtheliterature

and use thecrudebirthrate.See, tor

example,Branderand Dowrick(1994).

This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Thu, 19 Feb 2015 18:36:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DO HIGH BIRTH RATES HAMPER ECONOMIC GROWTH?

113

Table 1.- SummaryStatistics of Variables

Variables

Annualgrowthof realpercapitaGDP

Annualpopulation

growthrate

Birthrate(1/1000)

of minority

Proportion

population

Real percapitaGDP (1,000 yuanat

1952pricelevel)

enrollment

rate

Secondary-school

Investment

share

rate

In-migration

Growthof laborforceshare

Youthdependency

ratio

ratio

Old dependency

Tradeshare

Government

spendingshare

Mean

Standard

Deviation

112

112

112

112

0.081

0.014

18

0.107

0.032

0.004

4

0.157

0.003

0.004

6

0.001

0. 146

0.025

28

0.617

112

111

112

112

112

112

112

111

112

6.165

0.777

0.296

0.002

0.011

0.320

0.049

0.003

0.141

0.609

0.130

0.082

0.004

0.013

0.064

0.015

0.004

0.063

4.848

0.444

0.132

-0.004

- 0.024

0.179

0.022

0.000

0.052

7.932

0.998

0.525

0.027

0.060

0.429

0.114

0.028

0.369

Min

Max

in the range of (0, 2/1000), stageusingcovariatesin specification

thereis a high concentration

(2) oftable3. The IVs

about60% oftheobservations

areoutsidethisrange.In fact, includedare thefirstdifference

of theproportion

of minorthestandarddeviationis elevenout of a thousand,whichis itypopulation,and the ten-year,fifteen-year,

and twentytwice as large as the mean. In general,the distribution yearlagged LogGDP. For thelags of LogGDP, we experiof the minorityproportion mentby includingone, two, and then all threeof them

shows thatthe firstdifference

overtimehas a reasonablylargevariation,

and thisvariation respectively.

The f-statistics

and F-statisticsreportedin the

is not all caused by a few outliers.The proportionof tableare correctedforheteroskedasticity

and serialcorrelaminority

populationmayhave changedforseveralreasons. tion.

birthcontrolpolicy may have an

First,the affirmative

Results of these regressionsshow that the IVs have

accumulativeeffectover time.The accumulativeeffectis explanatorypowerforthe firstdifference

of the birthrate

in provinceswithlarge minority

more significant

popula- (columns1-3), as theP-valuesof thejointsignificance

tests

tionssuch as Xinjiang,Guanxi,and InnerMongolia. Sec- for IVs in all threecolumns are smallerthan 0.01. The

As partof proportion

ond, migration

may also changetheproportion.

of minority

populationhas a positiveeffecton

the developmentprocess,people frominlandand western thebirthrate,and thiseffectis

at the 1% level.

significant

to coastalprovinceswheremostof These resultsindicatethatthe one-child

provinceshave migrated

policy is indeed

theindustrial

centersare located.Migrationof thissortmay effective

in reducingthefertility

oftheHan Chineserelative

affecttheproportion

of minority

populationin a provincein to minorities.For the equation of the firstdifference

of

eitherdirection.

of China LogGDP, the

Moreover,thecentralgovernment

joint significanceteststatisticforIVs is not

has deliberatelysent Han Chinese to westernprovinces,

significantwhen we use only the firstdifferenceof the

wheremostethnicgroupsare located,forgovernancepurproportionof the minoritypopulationand the ten-year

poses. This typeof migrationtendsto reducetheminority laggedLogGDP as IVs [column(4)], butitbecomessignifproportionin westernprovincesand increase it in other icantwhen we also includethe fifteen-year

or fifteen-year

provinces.Finally,the proportionmay also change if mi- and twenty-year

[columns

(5) and (6)].

lagged LogGDP

norityand Han have different

mortality

patterns.

This suggeststhatwe shoulduse all threelags of LogGDP

whereavailable, as well as the firstdifference

of the proIV. EmpiricalResults

of

as

IVs

in

our

GMM

estimaportion minority

population,

in

tions

order

to

avoid

the

weak

instrument

problemas

This sectionsystematically

testswhetherthe birthrate

raised

Bond

et

al.

and

Bond

(2001)

(2002).

by

has a negativeeffecton economicgrowth.We firstprovide

In table3, we reporttheGMM estimateswith/-statistics

thebasic resultsand thenconductsome sensitivity

tests.

thatare heteroskedasticity

robust.We apply the Blundell

and

Bond

(1998) two-stepestimator,using Windmeijer

A. Basic Results

correctionsto the covariancematrix.

(2005) finite-sample

To testwhetherthe IVs have explanatorypowerforthe To statistically

examinethevalidityof ourIVs, we conduct

twoendogenousvariables,we runregressionswiththefirst theHansenoveridentification

restriction

test.16

The P-values

differenceof the birthrate (BRt - /?,-i) and the first

differenceof the five-yearlagged LogGDP (\ogyt-\16The Hansentestis a testof

restrictions.

The jointnull

overidentifying

are correctlyexcluded from

\ogyt-2)as dependentvariables,and reportthe resultsin hypothesisis thatthe excluded instruments

thestructural

growthequation,and thatthestructural

equationis correctly

table2. Note thatGMM does nothave a first-stage

regresdistributed

as

specified.Underthenull,theteststatisticis asymptotically

sion. Thus, we can thinkof these regressionsas the first c/i/-squared

in thenumberof overidentifying

restrictions.

We employthe

In thiscase, thetest

stageof a two-stageleastsquaresapproach,withthesecond efficientGMM estimatorallowingheteroskedasticity.

This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Thu, 19 Feb 2015 18:36:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE REVIEW OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS

114

Table 2- RegressionsExaminingthe ExplainingPower of InstrumentalVariables for the First Differenceof the Birth Rate and the First

Differenceof the Five-yearLagged LogGDP

DependentVariables:

oftheFive-year

FirstDifference

LaggedLogGDP

FirstDifference

of theBirthRate

Fifteen-year

laggedLogGDP

(3)

0.014***

(4.85)

-0.002*

(-1.84)

0.012***

(4.56)

0.0001

(0.01)

-0.002

(-0.71)

0.015***

(4.56)

-0.003

(-0.58)

0.007

(0.69)

-0.007

(-0.90)

0.632

(1.70)

-0.057

(-0.63)

-0.001

(-0.25)

-0.005

(-0.63)

0.009***

(2.91)

0.010***

(3.29)

0.008**

(2.50)

-0.008*

(-1.72)

-0.0003

(-0.04)

-0.015***

(-3.61)

-0.003

(-0.36)

0.459**

(1.98)

-0.099

(-0.20)

0.248

(0.64)

0.577

(1.40)

1.034**

(2.38)

Twenty-year

laggedLogGDP

Othervariables

Secondary-school

enrollment

(firstdifference)

Investment

share(firstdifference)

Period1983-1988

Period1988-1993

Period1993-1998

Jointsignificance

testof IVs

(E-statistics)

(P-value)

Provinces

Observations

/^-squared

15.68

<0.01

28

83

0.58

0.016***

(4.17)

0.014***

(3.53)

11.14

<0.01

28

56

0.65

0.024***

(3.38)

14.36

<0.01

28

28

0.81

(5)

(6)

0.262

(0.76)

1.164***

(5.74)

- 1.245***

(-6.24)

0.275*

(1.75)

0.945***

(4.42)

0.048

(0.17)

-1.1 13***

(-6.60)

(4)

(2)

(1)

IVs

of minority

Proportion

population

(firstdifference)

Ten-yearlaggedLogGDP

1.65

0.21

28

83

0.95

0.145

(0.68)

0.163

(0.50)

0.503*

(1.78)

0.236

(0.79)

0.587**

(2.22)

0.908***

(3.39)

0.605*

(1.72)

14.85

<0.01

28

56

0.98

38.48

<0.01

28

28

0.99

levelsof 10,5, and 1%. LogGDP is thelog of realpercapitaGDP. We

in parentheses.

/-statistics

thatarerobustto heteroskedasticity

andserialcorrelation

Notes:We report

*, **, and *** represent

significance

enrollment

rate(Guangxiprovincefortheperiod1983-1988).

lose one observation

in regressions

(1) and (4) becausethereis one missingvalue forthevariablesecondary-school

in table

in all regressions

fortheHansenJ-statistics

reported

3 are largerthan0.1, whichsuggeststhatconditionalon a

correctly

specifiedmodel,and conditionalon at leastone of

thereis

theinstrumental

variablesbeinga valid instrument,

no evidence to reject the validityof these IVs. We also

and secondtestsforthefirst-order

reporttheArellano-Bond

residuals.

orderserial correlationsin the first-differenced

The teststatisticssuggestthatwe can rejectthenull of no

first-order

serialcorrelation,

butwe cannotrejectthenullof

no second-orderserial correlation(only the latteris a

necessaryconditionforconsistentestimates).

that

Regressionresultsare consistentwiththehypothesis

economicgrowthdecreaseswiththebirthrate.In the first

column,we reporta regressionwith the birthrate, the

five-year

laggedreal percapitaGDP, and timedummiesas

variables.This regressionshows thatthebirth

independent

rate has a negativeeffecton economic growth,and this

effectis significant

at the 10% level.This simpleregression

that

Chinese

suggests

poor

provincesare notconvergingto

and

richones,sinceinitialGDP has a verysmallcoefficient

it is notsignificant

at the 10% level.

variables

Regression1 mayhaveomittedmanyimportant

side of thegrowthequation.We now add

on theright-hand

statisticis Hansen'sJ-statistic,

whichis theminimizedvalue of theGMM

criterion

function.Note thatthetestrelieson theassumptionthatat least

one of the instruments

is valid. For further

discussionsee, forexample,

Hayashi(2000, pp. 227-228, 407, 417).

thesevariablesin column(2). Followingtheliterature

(Levineand Renelt,1992; Temple,1999), thecontrolvariables

rateandtheinvestenrollment

includethesecondary-school

mentshare.We keep a minimumnumberof controlvariteststo

ables hereand leave morecomprehensive

sensitivity

thenextsubsection.

Aftercontrollingfor other variables that affectGDP

growth,it stilldecreaseswiththebirthrate.In column(2),

the coefficientof the variable birthrate is negativeand

oftheeffectmore

at the1% level.The magnitude

significant

than doubled with other variables controlledfor. Some

show

simple calculationsusing the estimatedcoefficients

thatthedeclineof thebirthratehas madea reasonablylarge

to China's economic growth.In the sample

contribution

period(1978-1998), China'sbirthratedecreasedby 1 outof

1,000 everyfive years,which impliesan increaseof the

annual per capita GDP growthrate by 0.9 percentage

or about 11% of the annual growthrateof 8.1%

points,17

thatChina's provincesachievedin the sampleperiod.The

percapitaGDP, thatis,

impliedincreasein thesteady-state

the permanentimprovementof the living standardsof

17A decreaseof thebirthrate one would increasethegrowthrateof

by

periodby 4.5%, wherewe have used the

per capita GDP in thefive-year

and the mean values of the independentvariables

estimatedcoefficients

fortheprediction.This five-year

growthratecan be convertedto a 0.9%

annual growthrate,with a 95% confidenceintervalof (0.004, 0.014),

whichis calculatedfromthedelta method.

This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Thu, 19 Feb 2015 18:36:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DO HIGH BIRTH RATES HAMPER ECONOMIC GROWTH?

115

Table 3.- GMM Estimatesof the Effectof the Birth Rate on GDP Growth

of LogGDP

Dependentvariable:Firstdifference

GMM

(SYS)

(2)

GMM

(DIF)

(3)

-0.036***

(-3.40)

-0.249*

(-1.85)

-0.174

(-0.67)

0.442

(1.02)

-0.034**

(-2.72)

-0.301

(-1.03)

-0.132

(-0.27)

0.352

(1.31)

GMM

(SYS)

(1)

Birthrate

Five-yearlaggedLogGDP

enrollment

Secondary-school

-0.016*

(-1.82)

-0.023

(-0.31)

0.489**

(2.11)

share

Investment

rate

In-migration

Growthof laborforceshare

ratio

Youthdependency

0.589

(1.44)

Tradeshare

GMM

(SYS)

(4)

-0.027**

(-2.17)

-0.134

(-1.19)

-0.045

(-0.18)

0.579*

(1.89)

1.572

(0.45)

0.0001

(0.68)

Government

spendingshare

Period1983-1988

Period1988-1993

Period1993-1998

restriction

Hansentestof overidentification

(HansenJ-statistics)

(P-value)

testforFirst-order

serialcorrelation

Arellano-Bond

(z-statistics)

(P-value)

serialcorrelation

Second-order

(z-statistics)

(P-value)

Provinces

Observations

GMM

(SYS)

(5)

-0.031**

(-2.33)

-0.293*

(-1.71)

-0.174

(-0.62)

0.438

(1.50)

0.694

(1.49)

9.732*

(1.74)

-0.053

(-0.12)

0.074

(1.44)

0.362***

(4.48)

0.261*

(1.77)

GMM

(SYS)

(6)

-0.027**

(-2.09)

-0.157

(-0.99)

-0.129

(-0.47)

0.551

(0.16)

0.0001

(0.95)

7.912*

(1.91)

0.011

(0.04)

0.097**

(2.24)

0.357***

(5.76)

0.213*

(1.94)

0.095***

(3.19)

0.249***

(6.25)

0.102

(1.43)

0.058

(1.12)

0.348***

(4.67)

0.211

(1.67)

0.089

(0.98)

0.390**

(2.60)

0.290

(1.20)

0.091**

(2.20)

0.349***

(5.75)

0.187**

(2.51)

12.23

0.14

10.48

0.23

4.66

0.46

11.53

0.17

13.02

0.11

12.21

0.14

-2.12

0.03

1.10

0.27

28

112

-1.56

0.11

1.38

0.17

28

111

-1.50

0.13

1.36

0.17

28

83

-1.81

0.07

1.20

0.23

28

111

-1.71

0.09

1.38

0.17

28

111

-1.87

0.06

1.20

0.23

28

111

inparentheses.

robust/-statistics

arereported

levelsof 10,5, and 1%. LogGDP is thelog ofrealpercapitaGDP. All specifications

Notes:Heteroskedasticity

*, **, and *** represent

inthetabletreat

significance

of thebirthrateandthefirst

difference

of five-year

thefirst

difference

estimatethefirst-differenced

difference

of theproportion

laggedLogGDP as endogenousvariables.All specifications

equationswiththefirst

and theten-year,

and twenty-year

of minority

fifteen-year

laggedLogGDP (whenthelags exist)as IVs. FortheSYS-GMM specifications

[columns(1-2) and (4-6)], we also havethreeLogGDP-level

population

difference

as IVs forthelaggedLogGDP on theright-hand

side. We lose one observation

in regressions

2-6 becausethereis one missingvalue forthevariablesecondary-school

equationswiththelaggedfirst

rate(Guangxiprovincefortheperiod1983-1988).

enrollment

Chinese, is 14.3%,18with a 95% confidenceintervalof are biased. They argue that the OLS estimateis biased

(-0.026,0.311).

upward,whiletheFE estimateis biaseddownward,andthus

Withthecontrolvariablesin column(2), thecoefficient theyprovidethe upper and lower bounds forbiases. We

of thelaggedpercapitaGDP becomeslargerin magnitude estimatethesame equationas thatin column(2) usingOLS

The investment

sharein col- and FE estimators.

and is marginally

The OLS estimateof thecoefficient

on

significant.

umn (2) has a strongpositive effecton growth,with a the lagged LogGDP is -0.061, and the FE estimateis

The secondary-school -0.307. We can see thattheDIF-GMM estimate(-0.301)

coefficient.

positiveand significant

at the 10% level.

rateis notsignificant

is very close to the FE estimate,suggestinga potential

enrollment

In the thirdcolumn,we reporta regressionusing the downwardbias withtheDIF-GMM estimate.As a contrast,

DIF-GMM estimator.The estimatedcoefficientof the theSYS-GMM estimateis -0.249, whichcomfortably

lies

laggedGDP is smallerthanthatoftheSYS-GMM estimator betweentheupperand lowerbounds.These resultssuggest

mayindeedbe a betterchoice.

reportedin column (2), suggestingthat the DIF-GMM thattheSYS-GMM estimator

is morelikelyto be biaseddownwardas arguedby

estimator

Bond et al. (2001). Bond et al. (2001) also suggestthatone

B. RobustnessTests

can use theordinary-least-squares

(OLS) and simplefixedtheGMM estimators In thissection,we testthe robustnessof our main estieffect(FE) estimatesto checkwhether

18The

of the steady-state

per capita GDP with

impliedsemielasticity

respectto thebirthrateis -0.036/0.249 = -0.143. Thus, a decrease of

the birthrateby one would increasethe steady-state

per capita GDP by

14.3%.

matesof theeffectof thebirthrateon economicgrowth.We

conductthese tests by includingotherdemographicand

institutionalvariables that may covary with economic

growth.The firstdemographicvariablewe includeis the

This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Thu, 19 Feb 2015 18:36:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

116

THE REVIEW OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS

could make our graphicvariablesare endogenousin the same way as the

rate. Omittingin-migration

in-migration

variablescould be endogenousas

IVs invalid.Forexample,ifprovinceswithsmallerminority birthrateis. Institutional

could be endogenousbecause

trade

well.

For

and

attract

from

faster

example,

in-migration provpopulationsgrow

inces withmoreminorities,

and if minoritiesand Chinese foreigncountriesare more likelyto tradewithprovinces

will tend thathave highgrowthpotential.Ideally,we shoulduse IVs

thenin-migration

havean equal chanceto migrate,

to increasethe proportionof minoritiesin the receiving to identifyall these variables,but empirically,it is very

IVs forthem.Nonetheless,the

to findappropriate

provinces.Since migrationin this example is correlated difficult

with both growthand the IV, that is, the proportionof burdenof finding

good IVs in thiscontextis nottoo greatin

in examiningwhether

it in thegrowthregressionwill invali- ourcontext.We are mainlyinterested

minorities,

omitting

of thesevariableswiththebirthratereduces

thecorrelation

date thisIV.

ofgrowthwiththebirthratebya large

Priorresearchhas also shownthatthe populationstruc- thepartialcorrelation

we

find

it

is notthecase.

and

amount,

and

more

the

share

of

labor

force

and

ture,

specifically

extremevaluesof variablesaffect

to

test

whether

Finally,

have

an

effect

on

economic

youthdependencyratio,may

we

have carriedout regressionsthat

our

estimation

results,

growth(Bloom & Williamson,1998; Kelley & Schmidt,

with

extremevalues for the GDP

exclude

observations

2005; and others).Because thesevariablesare also correWe

or theirfirstdifferences.

the

share,

rate,

minority

growth

lated withthe birthrate,includingthemmay reduce the

do

not

find

that

the

results

change

qualitatively.

empirical

explanatory

powerof thebirthrateitself.In fact,it is likely

we do notreporttheseregressions.

thatthroughthese population-structure

variablesthe birth Due to space limitations,

our

To

GMM

summarize,

regressionsshow consistently

rateexertsits effecton growth.

decreases

withthebirthrateforthe

that

economic

growth

Growthregressionsincludingthese demographicvariThis

of

Chinese

findingis robusteven if

sample

provinces.

ables continueto showthatthebirthratehas an independent

and institutional

we

for

a

number

of

control

demographic

effecton economicgrowth.The fourthcolumnof table 3

the

Malthusian

variables.

Our

prediction

findings

support

reportsa GMM regressionwith threenew independent

for

to

economic

that

birth

rates

are

detrimental

growth

high

variables:the in-migration

rate,the growthof labor force

like China.

a

developing

country

share,and youthdependencyratio. Controllingfor these

variables,thebirthratestillhas a negativeand significant

V. Conclusion

coefficient.The magnitudesof the coefficientsand the

of thesteady-state

impliedsensitivity

percapitaGDP to the

In thispaper,we examinetheimpactof thebirthrateon

birthrate are not much different

fromthose of previous economic growthby using a data set of 28 provincesin

regressions.However,none of thesenewlyincludedvari- China. We findthatthebirthratehas a negativeimpacton

ables is significant.

economicgrowth,and thisfindingis robusteven afterwe

The secondset of variablesthatmaycovarywithgrowth controlfora numberof demographicand institutional

variis institutional

or reform

variables.These variablesare from ables. Our findingprovidessome new evidencethatshows

ar- the negative causal effectof population on economic

two relatedliteratures.

The empiricalgrowthliterature

suchas government

size and trademay growth,as assertedby Malthus.

guesthatinstitutions

have an effecton growth(Barro, 1991; Levine & Renelt,

China startedits uniquepopulationcontrolpolicyin the

on China's economicreformsargues late 1970s. Our studyis among the firstto providesome

1992). The literature

thatthe"open-door"policyand marketization

mayhave an evidencethatcan be a basis forevaluatingtheeffectof this

important

positiveeffecton growth(Bao et al., 2002; Jin, populationcontrolpolicy.Whilethebirthcontrolpolicyhas

Qian, and Weingast,2005; Li & Zhou, 2005). To capture manynegativeaspectsforhumanbeings,and theremaybe

theseinstitutional

or reform

we followtheliterature otherpolicies that can controlpopulation,the one-child

effects,

to therapidgrowthof

and includethetradeshareas a percentageof GDP and the policymay indeedhave contributed

the

late

1970s.

since

the

Chinese

a

share

as

a

of

GDP

economy

(as

government

spending

percentage

size and marketization)

as control

measureof government

REFERENCES

variables.

vari- Anderson,Barbara,and BrianSilver,"EthnicDifferencesin Fertilityand

The regressionresultsincludingtheseinstitutional

Sex Ratiosat Birthin China: EvidencefromXinjiang,"Population

ables again supportthe hypothesisthateconomic growth

and DevelopmentReview49:2 (1995), 211-226.

decreaseswiththebirthrate[columns(5) and (6)]. The birth

Arellano,Manuel, and StephenBond, "Some Tests of Specificationfor

ratehas a negativecoefficient,

and itis significant

at the5%

Panel Data: MonteCarlo Evidenceand an Applicationto EmploymentEquations,"ReviewofEconomicStudies58 (1991), 277-297.

level. The tradeshare has an expectedpositiveeffecton

Manuel,and OlympiaBover,"AnotherLook at theInstrumental

but the Arellano,

economic growthand is marginallysignificant,

Variable Estimationof Error-Component

Models," Journal of

shareis not significant.

Econometrics68 (1995), 29-51.

government-spending

In interpreting

resultsassociatedwithcolumns4-6, we Bao, Shuming,Gene Chang,WingThye Woo, and JettreySachs, OeographicFactorsand China's RegionalDevelopmentUnderMarket

should exercisesome caution.Both the demographicand

Reforms,1978-1998," China EconomicReview 13:1 (2002), 89111.

institutional

variables could be endogenous.The demo-

This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Thu, 19 Feb 2015 18:36:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DO HIGH BIRTH RATES HAMPER ECONOMIC

Barlow,Robin,"BirthRate and Economic Growth:Some More Correlations,"Populationand DevelopmentReview20 (1994), 153-165.

Barro, Robert,"Economic Growthin a Cross Section of Countries,"

QuarterlyJournalof Economics 106 (1991), 407-444.

Choice in a Model of Economic

Barro,Robert,and GaryBecker, Fertility

Growth,"Econometrica57:2 (1989), 481-502.

Barro,Robert,and Xavier Sala-i-Martin,Economic Growth(New York:

McGraw-Hill,1995).

betweentheQuantity

Becker,Gary,and GreggLewis, "On theInteraction

and Quality of Children,"Journal of Political Economy 81:2

(1973), S279-288.

Becker, Gary, Kevin Murphy,and Robert Tamura, "Human Capital,

Fertilityand Economic Growth,"Journalof Political Economy

98:5 (1990), S12-S37.

Journalof DevelopBlock, StevenA., "Does AfricaGrow Differently?"

mentEconomics65 (2001), 443^67.

Williamson,"DemographicTransitionsand

Bloom, David, and Jeffrey

Economic Miracles in EmergingAsia," WorldBank Economic

Review 12:3 (1998), 419-455.

Blundell,Richard,and StephenBond, "Initial Conditionsand Moment

in Dynamic Panel Data Models," Journalof EconoRestrictions

metrics87 (1998), 115-143.

"GMM EstimationwithPersistentPanel Data: An Applicationto

ProductionFunctions,"EconometricReviews19 (2000), 321-340.

Bond, Stephen,"Dynamic Panel Data Models: A Guide to Micro Data

Methodsand Practice,"PortugueseEconomic Journal 1 (2002),

141-162.

and JonathanTemple,"GMM Estimation

Bond, Stephen,Anke Hoeffler,

of EmpiricalGrowthModels," CEPR discussionpaper no. 3048

(2001).

Boserup,Ester,Populationand TechnicalChange: A StudyofLong-Term

Trends(Chicago: Universityof Chicago Press, 1981).

Brander,James A., and Steve Dowrick, "The Role of Fertilityand

Populationin Economic Growth:EmpiricalResultsfromAggregate Cross-nationalData," Journalof Population Economics 1

(1994), 1-25.

Caselli, Francesco,GerardoEsquivel, and FernandoLefort,"Reopening

the ConvergenceDebate: A New Look at Cross-Country

Growth

Empirics,"Journalof EconomicGrowth1 (1996), 363-389.

Coale, A., "PopulationTrends and Economic Development, in Jane

Menken (Eds.), WorldPopulation and US Policy: The Choice

Ahead (New York:W. W. Norton,1986).

Deng, Hongbi,PopulationPolicies TowardEthnicMinoritiesin China

(Chongqing:ChongqingPress, 1995).

Ehrlich,Isaac, and FrancisLui, "Intergenerational

Trade,Longevity,and

Economic Growth,"Journalof Political Economy99:5 (1991),

1029-1059.

Galor,Oded, and David Weil, "The GenderGap, Fertilityand Growth,"

AmericanEconomicReview86 (1996), 374-387.

Hardee-Cleaveland,Karen, and JudithBanister,"FertilityPolicy and

in China, 1986-88," Populationand Development

Implementation

Review 14 (1988), 245-286.

ProducHayami,Yujiro,and VernonRuttan,"BirthRate and Agricultural

tivity,"in Gale Johnsonand Ronald Lee (Eds.), BirthRate and

Economic Development:Issues and Evidence (Madison: Universityof WisconsinPress, 1987).

Hayashi,F, Econometrics(Princeton:PrincetonUniversityPress,2000).

Hazledine, Tim, and R. Scott Moreland, "Population and Economic

Growth:A World Cross-sectionStudy,"this review 59 (1977),

253-263.

Islam,Nazrul,"GrowthEmpirics:A Panel Data Approach,"The Quarterly

Journalof Economics 110(1995), 1127-1170.

Jin,Hehui,YingyiQian, and BarryWeingast,"Regional Decentralization

and Fiscal Incentives:Federalism,"Journalof Public Economics

89:9-10(2005), 1719-1742.

Jones,Charles, "Growth:With or withoutScale Effects?"American

EconomicReview89 (1999), 139-144.

Kelley,Allen C, "Economic Consequencesof PopulationChange in the

ThirdWorld,"Journalof Economic Literature26 (1988), 16851728.

GROWTH?

117

Kelley, Allen C, and Robert M. Schmidt,"Population and Income

Change: Recent Evidence," WorldBank Discussion Paper 249

(1994).

"AggregatePopulationand Economic GrowthCorrelations:The

Role of the Componentsof DemographicChange," Demography

32 (1995), 543-555.

"Evolutionof RecentEconomic-Demographic

Modeling:A Synthesis,"Journalof PopulationEconomics 18 (2005), 275-300.

Kremer,Michael, "PopulationGrowthand TechnologicalChange: One

Million B.C. to 1990," QuarterlyJournal of Economics 108

(1993), 681-716.

Levine,Ross, and David Renelt,"A Sensitivity

Analysisof Cross-Country

Growth Regressions,"American Economic Review 82 (1992),

942-963.

Lewis, Arthur,"Economic Development with UnlimitedSupplies of

Labour,"ManchesterSchool 22 (1954), 139-191.

Li, Hongbin,and Li-an Zhou, "PoliticalTurnoverand Economic Performance:The IncentiveRole of PersonnelControlin China,"Journal

of Public Economics89:9-10 (2005), 1743-1762.

to the

Mankiw,Gregory,David Romer,and David Weil,"A Contribution

Empiricsof Economic Growth,"QuarterlyJournalof Economics

107:2 (1992), 407^37.

McNicoll, Geoffrey,"Consequences of Rapid PopulationGrowth:An

Overviewand Assessment,"Populationand DevelopmentReview

10 (1984), 537-544.

Park, Chai Bin, and Jing-qingHan, "A MinorityGroup and China's

One-childPolicy: The Case of the Koreans," Studies in Family

Planning21:3 (1990), 161-170.

Peng, Peiyun,Encyclopediaof BirthControlPolicies in China (Beijing:

The People's Press, 1996).

Pingali,Prabhu,and Hans Binswanger,"PopulationDensityand AgriculturalIntensification:

A Studyof the Evolutionof Technologiesin

Tropical Agriculture,"in Gale Johnsonand Ronald Lee (Eds.),

Birth Rate and Economic Development: Issues and Evidence

(Madison: Universityof WisconsinPress, 1987).

Qian, Zhenchao,"Progressionto Second Birthin China: A Studyof Four

Rural Counties,"PopulationStudies51:2 (1997), 221-228.

Romer,Paul, "IncreasingReturnsand Long-Run Growth,"Journalof

Political Economy94:5 (1986), 1002-1037.

Capital Accumulationin the Theoryof Long Run Growth,in

RobertBarro (Ed.), Modern Business Cycle Theory(Cambridge:

HarvardUniversityPress, 1989).

"EndogenousTechnologicalChange,"Journalof Political Economy98:5 (1990), S7 1-S102.

Shioji, Etsuro,"Public Capital and Economic Growth:A Convergence

Approach,"Journalof EconomicGrowth6 (2001), 205-227.

Short,Susan, and FengyingZhai, LookingLocally at China's One-child

Policy,"Studiesin FamilyPlanning29:4 (1998), 373-387.

The

Simon,JulianL., "The Effectof PopulationDensityon Infrastructure:

Case of Road Building," Economic Developmentand Cultural

Change 23:3 (1975), 453-568.

"On AggregateEmpiricalStudiesRelatingPopulationVariablesto

EconomicDevelopment,"Populationand DevelopmentReview15

(1989), 323-332.

to theTheoryof EconomicGrowth,"

Solow, RobertM., "A Contribution

QuarterlyJournalof Economics70 (1956), 65-94.

StateStatisticalBureau(SSB), China StatisticalYearbook(Beijing: China

StatisticPress, 1980-1999).

Basic Data of China's Population(Beijing: China StatisticPress,

1994).

StatisticalData and Materialson 50 YearsofNew

Comprehensive

China (Beijing: China StatisticPress, 1999).

Temple,Jonathan,"The New GrowthEvidence," Journalof Economic

Literature37:1 (1999), 112-156.

Wang, Ping, Chong K. Yip, and Carol Scotese, "FertilityChoice and

Economic Growth: Theory and Evidence," this review 76:2

(1994), 255-266.

Windmeijer,Frank, "A Finite Sample Correctionfor the Variance of

Linear EfficientTwo-StepGMM Estimators,"Journalof Econometrics126(2005), 25-51.

This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Thu, 19 Feb 2015 18:36:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Вам также может понравиться

- This Content Downloaded From 111.68.96.34 On Tue, 03 Aug 2021 05:26:40 UTCДокумент35 страницThis Content Downloaded From 111.68.96.34 On Tue, 03 Aug 2021 05:26:40 UTCmani836Оценок пока нет

- Thesis On Population Growth PDFДокумент6 страницThesis On Population Growth PDFf1t1febysil2100% (2)

- Literature Review On Population and Economic GrowthДокумент4 страницыLiterature Review On Population and Economic GrowthafmzuomdamlbzaОценок пока нет

- Childbearing Age, Family Allowances and Social SecurityДокумент30 страницChildbearing Age, Family Allowances and Social SecurityNatalia GuinsburgОценок пока нет

- Thesis Statement On Population ControlДокумент5 страницThesis Statement On Population Controlafbteepof100% (2)

- Why Fertility ChangesДокумент32 страницыWhy Fertility ChangesMariyam SarfrazОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 196.189.147.205 On Sun, 08 Jan 2023 09:10:12 UTCДокумент20 страницThis Content Downloaded From 196.189.147.205 On Sun, 08 Jan 2023 09:10:12 UTCKk GgОценок пока нет

- Financial Incentives and FertilityДокумент21 страницаFinancial Incentives and FertilityNatalia GuinsburgОценок пока нет

- Population Growth Thesis StatementДокумент8 страницPopulation Growth Thesis Statementgjcezfg9100% (2)

- Dissertation On Population GrowthДокумент5 страницDissertation On Population GrowthSomeToWriteMyPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Gross 2005Документ11 страницGross 2005pomajoluОценок пока нет

- Research Paper On Overpopulation in ChinaДокумент4 страницыResearch Paper On Overpopulation in Chinafvfj1pqe100% (1)

- Economic Growth and Economic DevelopmentДокумент13 страницEconomic Growth and Economic DevelopmentJofil LomboyОценок пока нет

- Population, Poverty, and Sustainable DevelopmentДокумент30 страницPopulation, Poverty, and Sustainable DevelopmentHermawan AgustinaОценок пока нет

- Population and Environment Lecture AguirreДокумент26 страницPopulation and Environment Lecture AguirreKido GlobeОценок пока нет

- Gabriel-Lesson 2 - Activity 2.1 and Post-AssessmentДокумент4 страницыGabriel-Lesson 2 - Activity 2.1 and Post-AssessmentLucille May GabrielОценок пока нет

- Galor - Gender Gap, Fertility and GrowthДокумент15 страницGalor - Gender Gap, Fertility and GrowthblablaОценок пока нет

- De La CroixДокумент24 страницыDe La Croixcarlos ortizОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Population Growth On Economic Development of Barangay Purisima, Tago, Surigao Del SurДокумент27 страницThe Impact of Population Growth On Economic Development of Barangay Purisima, Tago, Surigao Del SurTrisha SimbolasОценок пока нет

- Jones RDBased 1995Документ27 страницJones RDBased 1995shachirai17Оценок пока нет

- Growth, Fertility and Human Capital: A Survey: Robert TamuraДокумент47 страницGrowth, Fertility and Human Capital: A Survey: Robert TamuraCosmin MogaОценок пока нет

- Sample Thesis About Population GrowthДокумент8 страницSample Thesis About Population GrowthGhostWriterCollegePapersDesMoines100% (2)

- Effects of High Fertility On Economic Development: Emmanuel ObiДокумент12 страницEffects of High Fertility On Economic Development: Emmanuel ObiJude Daniel AquinoОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S2666622723000382 MainДокумент11 страниц1 s2.0 S2666622723000382 MainconnОценок пока нет

- Hanson Prescott Malthus To SolowДокумент14 страницHanson Prescott Malthus To SolowMauricio Giovanni Valencia AmayaОценок пока нет

- Zeng 2016Документ9 страницZeng 2016fahar26Оценок пока нет

- Population Growth Research Paper TopicsДокумент4 страницыPopulation Growth Research Paper Topicsgz8qs4dn100% (1)

- China's One Child Policy Research PaperДокумент13 страницChina's One Child Policy Research PaperZaraОценок пока нет

- Thesis OverpopulationДокумент7 страницThesis Overpopulationafkollnsw100% (2)

- Schultz EconomicModelFamily 1969Документ29 страницSchultz EconomicModelFamily 1969Rafi KurniawanОценок пока нет

- Social SpendingДокумент25 страницSocial SpendingChaudhry Muhammad RazaОценок пока нет

- Why Fertility Changes - Charles HirschmanДокумент32 страницыWhy Fertility Changes - Charles HirschmanGabriela BaruffiОценок пока нет

- Barro 2013 Health and Economic GrowthДокумент38 страницBarro 2013 Health and Economic GrowthorntrixОценок пока нет

- Determinants of Economic Growth Implications of The Global Evidence For ChileДокумент37 страницDeterminants of Economic Growth Implications of The Global Evidence For ChileDavid C. SantaОценок пока нет

- Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization: Management Fads, Pedagogies, and Other Soft TechnologiesДокумент15 страницJournal of Economic Behavior & Organization: Management Fads, Pedagogies, and Other Soft TechnologieskrunoeisennОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 193.140.201.95 On Fri, 26 May 2023 21:00:04 +00:00Документ12 страницThis Content Downloaded From 193.140.201.95 On Fri, 26 May 2023 21:00:04 +00:00Meltem PaşaОценок пока нет

- Jvad 025Документ39 страницJvad 025oakpacificОценок пока нет

- Article For PopulationДокумент8 страницArticle For Populationmuhammadsiddique990Оценок пока нет

- Intergenerational Mobility and The Rise and Fall of Inequality: Lessons From Latin AmericaДокумент22 страницыIntergenerational Mobility and The Rise and Fall of Inequality: Lessons From Latin AmericaValentina PizaОценок пока нет

- Case Study: International Political EconomyДокумент15 страницCase Study: International Political Economyraja_hashim_aliОценок пока нет

- The Historical Fertility Transition A Guide For Economists - Guinnane 2011Документ27 страницThe Historical Fertility Transition A Guide For Economists - Guinnane 2011Tym SОценок пока нет

- Accounting For Fertility Decline During The Transition To GrowthДокумент46 страницAccounting For Fertility Decline During The Transition To GrowthenigmauОценок пока нет

- Paper 9ErB6T49Документ38 страницPaper 9ErB6T49Betel Ge UseОценок пока нет

- Health - and - economic - growth (1) -مفتوحДокумент62 страницыHealth - and - economic - growth (1) -مفتوحASSIAОценок пока нет

- Research Paper Population ControlДокумент4 страницыResearch Paper Population Controlegzt87qn100% (1)

- Module 2Документ6 страницModule 2Yatan AnandОценок пока нет

- Thesis On Population GeographyДокумент6 страницThesis On Population Geographyggzgpeikd100% (2)

- Literature Review On Population GrowthДокумент5 страницLiterature Review On Population Growthafmziepjegcfee100% (1)

- HallJonesQJE PDFДокумент35 страницHallJonesQJE PDFAlejandra MartinezОценок пока нет

- Hall & Jones (1999)Документ35 страницHall & Jones (1999)Charly D WhiteОценок пока нет

- Islam (1995) - Growth Empirics A Panel Data ApproachДокумент45 страницIslam (1995) - Growth Empirics A Panel Data ApproachvinitusmendesОценок пока нет

- Grossman, Helpman 1994Документ38 страницGrossman, Helpman 1994L Laura Bernal HernándezОценок пока нет

- Children As Public GoodsДокумент6 страницChildren As Public Goodssteph otthОценок пока нет

- Attachment 4Документ37 страницAttachment 4omwando mosotiОценок пока нет

- Overpopulation Research Paper ThesisДокумент8 страницOverpopulation Research Paper Thesisdnr16h8x100% (2)

- Overpopulation Introduction Research PaperДокумент5 страницOverpopulation Introduction Research Papervvgnzdbkf100% (1)

- Determinants of Economic GrowthДокумент118 страницDeterminants of Economic GrowthNabil Lahham100% (1)

- Dasgupta InequalityDeterminantMalnutrition 1986Документ25 страницDasgupta InequalityDeterminantMalnutrition 1986taruna64ssaОценок пока нет

- State Laws Polling Place Electioneering 2014Документ11 страницState Laws Polling Place Electioneering 2014FungoОценок пока нет

- Razin, Sadka - A Pecking Order Among FDI, Debt and Portfolio Equity FlowsДокумент19 страницRazin, Sadka - A Pecking Order Among FDI, Debt and Portfolio Equity FlowsFungoОценок пока нет

- Whole Foods Regional Director (Africa)Документ2 страницыWhole Foods Regional Director (Africa)FungoОценок пока нет

- TestДокумент1 страницаTestFungoОценок пока нет

- Type Here - 3.984834 1992.416752 11954.50051 170.7785788Документ2 страницыType Here - 3.984834 1992.416752 11954.50051 170.7785788FungoОценок пока нет

- Python NotesДокумент5 страницPython NotesFungoОценок пока нет

- Ex15 SampleДокумент1 страницаEx15 SampleAlberto CastiñeirasОценок пока нет

- Type Here - 3.984834 1992.416752 11954.50051 170.7785788Документ2 страницыType Here - 3.984834 1992.416752 11954.50051 170.7785788FungoОценок пока нет

- Greetings DialogueДокумент1 страницаGreetings DialogueFungoОценок пока нет

- Gayathari's SC NotesДокумент32 страницыGayathari's SC NotesRakesh BussaОценок пока нет

- Population Distribution Cloze QuizДокумент3 страницыPopulation Distribution Cloze Quizapi-300330247Оценок пока нет

- SINOPEC Lubricant CompanyДокумент2 страницыSINOPEC Lubricant CompanyRaisul Islam NayanОценок пока нет

- Dynamics of The China-United Kingdom Commodity TradeДокумент20 страницDynamics of The China-United Kingdom Commodity TradeSyed Ahmed RizviОценок пока нет

- Homework 4 of 中国对外贸易Документ3 страницыHomework 4 of 中国对外贸易Shierly AnggraeniОценок пока нет

- 1.综合02.艾兹黑德:"17 世纪中国的大危机" (Adshead, SAM "The ...Документ321 страница1.综合02.艾兹黑德:"17 世纪中国的大危机" (Adshead, SAM "The ...Conference CoordinatorОценок пока нет

- Business Etiquette in ChinaДокумент9 страницBusiness Etiquette in ChinaBright ChenОценок пока нет

- The Historiography of The Jesuits in China - Brill ReferenceДокумент23 страницыThe Historiography of The Jesuits in China - Brill Referencepsfaria100% (1)

- Aphg Chapter 9Документ20 страницAphg Chapter 9Derrick Chung100% (1)

- Zhouli 周禮 (Www.chinaknowledge.de)Документ1 страницаZhouli 周禮 (Www.chinaknowledge.de)brandonscientiaОценок пока нет

- China 2005 - DK Eyewitness PDFДокумент683 страницыChina 2005 - DK Eyewitness PDFpuisne80% (5)

- The Green Register - Spring 2011Документ11 страницThe Green Register - Spring 2011EcoBudОценок пока нет

- Liu Yun Qiao's BaguazhangДокумент6 страницLiu Yun Qiao's BaguazhangMatt B. Parsons100% (2)

- Moses Kotane Lecture by Ibbo MandazaДокумент25 страницMoses Kotane Lecture by Ibbo MandazaTinashe Tyna MugutiОценок пока нет

- Visual Culture in Contemporary China Paradigms and Shifts by Xiaobing TangДокумент289 страницVisual Culture in Contemporary China Paradigms and Shifts by Xiaobing TangPedroОценок пока нет

- Chinese Compositional SytleДокумент111 страницChinese Compositional SytleTim ChongОценок пока нет

- Airline Leader - Issue 35 PDFДокумент76 страницAirline Leader - Issue 35 PDFRuben HoyosОценок пока нет

- Disinformation in The South China Sea Dispute by SC Justice Antonio CarpioДокумент56 страницDisinformation in The South China Sea Dispute by SC Justice Antonio CarpioBlogWatchОценок пока нет

- FijiTimes - Aug 32012 PDFДокумент48 страницFijiTimes - Aug 32012 PDFfijitimescanadaОценок пока нет

- Great Games, Local RulesДокумент267 страницGreat Games, Local RulesRose Martins100% (1)

- Funskool India Case StudyДокумент6 страницFunskool India Case StudyMegha Marwari100% (1)

- History of HanfuДокумент4 страницыHistory of HanfuAta0% (1)

- CCOT Essay StructureДокумент2 страницыCCOT Essay StructureFoldedNICkОценок пока нет

- ATW 2011 EkimДокумент72 страницыATW 2011 EkimdanisibrahimОценок пока нет

- The Rising Tide of Nationalism and Evaluation and Prospects of Asian Survival and Adaptation Amidst GlobalizationДокумент84 страницыThe Rising Tide of Nationalism and Evaluation and Prospects of Asian Survival and Adaptation Amidst GlobalizationRaven Dave Atienza75% (4)

- Book Review - Xiaobing Li - History of The PLAДокумент4 страницыBook Review - Xiaobing Li - History of The PLAMaverick BladeОценок пока нет

- 天公真经 Mantra Tuhan Yang Maha Kuasa - Tian Gong Zhen Jing.Документ4 страницы天公真经 Mantra Tuhan Yang Maha Kuasa - Tian Gong Zhen Jing.Kumpulan E-Book Tridharma (Tao, Khonghucu, Buddha)Оценок пока нет

- 2018 07 02 Bloomberg BusinessweekДокумент80 страниц2018 07 02 Bloomberg BusinessweekyodamОценок пока нет

- Economic Impact of CovidДокумент7 страницEconomic Impact of Covidrishi pereraОценок пока нет

- Pimsleur Mandarin Chinese I NotesДокумент22 страницыPimsleur Mandarin Chinese I NotesGraham Herrick100% (2)

- JON LANG International Urban Designs - Brands in Theory and PracticeДокумент9 страницJON LANG International Urban Designs - Brands in Theory and PracticeRohayah Che AmatОценок пока нет