Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Urban Stud 2012 Denis Jacob 97 114

Загружено:

Ioana EnglerАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Urban Stud 2012 Denis Jacob 97 114

Загружено:

Ioana EnglerАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

49(1) 97114, January 2012

Cultural Industries in Small-sized

Canadian Cities: Dream or Reality?

Jonathan Denis-Jacob

[Paper first received, July 2010; in final form, December 2010]

Abstract

This paper looks at the residential location of cultural workers in the smallest Canadian

cities, with the primary goal of understanding the factors making some more successful

than others in attracting them. The study examines employment in 13 cultural industries

in 109 small Canadian urban areas using data drawn from the 2006 Canadian census. Six

explanatory factors are put forward and entered into a regression model to explain the

location of cultural workers in small places: size, location with respect to metropolitan

areas, work structure, amenities, elderly populations and public-sector choices. The

results suggest that, beyond industry-specific production processes, the location of

cultural workers in small cities is also driven by residential and lifestyle preferences.

Introduction

Over the past decade, cultural industries

have attracted much attention from urban

researchers. An abundant literature draws

upon their potential role in urban economic

development (Florida, 2002b; Hall, 2000;

Landry, 2000; Markusen and King, 2003;

Scott, 2004) and in urban regeneration (Evans

2001; Hutton, 2009; Pratt, 2009). Cultural

industries are said to be contributing to urban

economies in several ways. First, they continue to grow, contributing to employment

creation in urban areas while other sectors are

experiencing decline (Scott, 2004). Secondly,

and perhaps more importantly, cultural

industries are regarded as driving forces for

the regeneration of post-industrial urban fabrics (Evans, 2001; Florida, 2008; Hutton, 2009;

Pratt, 2009), as well as a means to enhance

their attractiveness for mobile professionals

and capital (Florida, 2002a; Markusen and

King, 2003; Scott, 2004; Zukin, 1995). Others

see cultural industries as a means for boosting

self-confidence and community empowerment (Evans and Foord, 2006; Huber et al.,

1992). Culture has, in short, emerged as a key

component in local development strategies.

However, regeneration and economic development policies based on cultural industries

Jonathan Denis-Jacob is in the Spatial Analysis and Regional Economics Laboratory, Centre

Urbanisation Culture et Socit, National Institute of Scientific Research, University of Quebec, 385

rue Sherbrooke Est, Montral, Qubec, Canada H2X 1E3. E-mail: jonathan.denis-jacob@ucs.inrs.ca.

0042-0980 Print/1360-063X Online

2011 Urban Studies Journal Limited

DOI: 10.1177/0042098011402235

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

98Jonathan Denis-Jacob

have not been successful in all places. This

limited success is attributed, on the one hand,

to the exaggerated hope placed in culture-led

regeneration (Hall, 2000; Scott, 2004), but

also to the fact that cultural industries do not

necessarily flourish in all places. Indeed, cultural industries remain heavily concentrated

in a handful of cities at the top of the urban

hierarchy (Hall, 1998; Scott, 1999; Sereda,

2007). Research on the location of cultural

industries has traditionally focused on the

largest metropolitan areas. Yet recent studies have shown that some small cities also

exhibit high numbers of creative industries

and workers (Hills Strategies, 2006; Nelson,

2005; Petrov, 2007; Power, 2002). However,

these studies are either descriptive in nature

or look at creative occupations in general,

without differentiating between cultural/

creative sectors. More research is needed to

understand the rationale behind the location

of cultural workers employed in different sectors in small cities.

This paper looks at workers in 13 cultural

industries in small Canadian urban areas,

using employment data drawn from the 2006

Canadian census, with the aim of increasing

our understanding of their location factors

in these places. Six explanatory factors are

considered and tested as possible predictors

for the strong presence of cultural workers in

small cities: size, location, the work culture,

public-sector choices, amenities and elderly

populations.

Why Size Matters

Cultural industries are usually thought of as

metropolitan functions and evidence shows

that they are indeed. In North America, the

share of cultural employment in total employment is significantly higher in metropolitan

areas than elsewhere (Sereda, 2007). In the

UK, London accounts for a disproportionate

share of cultural employment (Pratt, 1997a,

1997b). Scott (2000) observed that about half

of cultural workers in the US were found in

urban areas with populations over a million,

with the majority concentrated in the two largest, New York and Los Angeles. City size can

therefore determine cities ability to attract

and develop cultural industries.

The concentration of cultural employment

in large metro areas must be addressed both

at the worker and at the firm levels. At the

worker level, the necessity of agglomeration

and of being near other talented and creative

people is central to the discussion around

the role of size (Castells, 1996; Hall, 2000).

The uncertainty associated with contractual

and freelance employment in the cultural

sector is a factor. Since a large proportion of

cultural workers are hired as freelancers, on

a short-term basis (Scott, 2004), they require

being in a place where they can keep abreast

of current trends and employment opportunities, including through social networking activities (Christopherson, 2002). By the

same token, many cultural workers, especially

artists, work across industries, making thick

employment centres more suitable for their

professional needs (Markusen and Schrock,

2006). The attraction of particular lifestyles

and amenities constitutes another factor

explaining the agglomeration of workers in

metro areas (Sassen, 1994). At the firm level,

explanations lie in the nature of their organisational structure. Many cultural industries

are characterised by flexible specialisation

(Storper and Christopherson, 1987; Shapiro

et al., 1992; Scott, 1999), an organisational

structure centred around a web of small,

independent and highly specialised firms

dealing with non-standardised production,

constantly interacting with one another and

able to adjust rapidly to changes in their

industry. Central to this model is the role

of outsourcing and contractual production

(Storper and Christopherson, 1987). Many

traditionally vertically integrated organisations, such as those in broadcasting and publishing, now externalise a considerable part

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

CULTURAL INDUSTRIES IN CANADA 99

of their production to smaller independent

firms, a practice that allows increased flexibility, specialised expertise and reduced production costs. This outsourcing process has led to

a substantial growth in the number of small

and specialised producers organised around

competitivecomplementary relationships

(Scott, 2004), resulting in further concentration in metro areas. For many small cultural

firms, some degree of spatial proximity is

essential because of the weight of specialised

labour, tacit knowledge, face-to-face contacts

and access to non-codified information.

Individual skills in cultural industries are

often the results of experience learning and

knowledge spill-over processes (Wenting,

2008), both of which usually require personal

interactions.

Finally, the fall of transport and communication costs over the past decades has accelerated the concentration of cultural production

in the largest metro areas (Krugman, 1991;

Sassen, 1994). The location choice of many

economic activities is the result of a trade-off

between economies of scale (from the concentration of production in one place) and

the cost of transporting the output (Polese

and Shearmur, 2005). For cultural industries,

for which outputs travel at almost no cost

across space, the largest metro areas become

the optimal locations, allowing them fully to

realise economies of scale.

In short, the odds are clearly stacked against

small places. However, an emerging literature

looks at so-called cultural-creative clusters

beyond the metropolis using quantitative

(Gibson and Connell, 2004; Hills Strategies,

2006; Nelson, 2005; Petrov, 2007; Power, 2002;

Waitt, 2006; Wojan, 2006) and qualitative

case study approaches (Evans and Foord,

2006; Gibson and Connell, 2004; Waitt and

Gibson, 2009). While most authors generally

acknowledge the overwhelming dominance of

large metropolitan areas in cultural production, they all point to the rise of some small

cities in cultural/creative industries.

Why Cultural Employment in

Small Cities?

The location of industries in small urban

areas has traditionally been associated with

the so-called crowding-out effect, a progressive out-migration (from the metropolis) of

economic activities (mostly manufacturing

and back-office activities) seeking out more

affordable land and labour costs in mid- and

small-sized cities (Henderson, 1997). Yet,

there has been no evidence to suggest that

high costs are systematically pushing cultural industries out of major metro areas as

they remain the primary places for cultural

production. Other factors, beyond urban size

and production costs, should be considered

to explain the presence of cultural workers

beyond the metropolis.

First, size together with location within a

certain threshold around large metropolitan

areas (100150 km) has proven meaningful in

explaining the location patterns of economic

activity in Canada and beyond (see Polse

and Shearmur, 2004; Polse and Champagne,

1999). For many economic activities, small size

and proximity to the metropolis are a double

advantage which permits both reduced operating costs (relative to the metropolis) and

easy access to metropolitan business functions

(Henderson, 1997). For cultural workers however, location with respect to metropolises is

not merely about production and transport

costs, but more about the very nature of work

and organisational structures. A significant

number of cultural firms are characterised

by flexible organisational structures where

individuals build their own schedule and do

not necessarily work from a fixed location.

Sectors such as the arts and film and video

production come to mind as activities which

can partly be produced from anywhere given

their low transport cost. However, although

a cultural worker/firm may produce and

create from an isolated location, chances are

slim to get new contacts in the same place.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

100Jonathan Denis-Jacob

This is where proximity to the large metro

area comes in. For those individuals taking

advantage of this flexibility and locating in

non-metropolitan settings, location on the

edge of the metropolis (say within a 100150

km radius) makes sense as frequent face-toface interactions with clients, partners and

institutions remain possible. Centrally located

small urban areas are therefore more likely

to capture those do-not-want-to-be-in-themetropolis cultural workers.

Yet location creates both opportunities and

disadvantages for small cities, depending on

how far away or close enough they are, relative to the large city. Waitt and Gibson (2009)

found that Wollongong in Australia has been

unsuccessful in developing a vibrant cultural

economy due in part to its close proximity

to Sydney, which keeps attracting most of

Wollongongs cultural workers and consumers.

Conversely, for small peripheral cities, distance

is a handicap as they often lack the market to

sustain year-round cultural activities, being

too far from metropolitan areas (Evans and

Foord, 2006). For instance, peripheral cities

such as Inverness (Scotland) or Timmins

(Ontario) suffer from their remote location,

being unable to attract metropolitan audiences

to local cultural events and activities.

A second possible factor is the absence

of a blue-collar legacy. Cultural industries

constitute a relatively new type of activities

in that they deal mainly with aesthetic and

semiotic dimensions (Scott, 2004). Their work

and organisational culture is hence different

from that of resource-based, construction

and heavy manufacturing industries. This

suggests that, in cities with a strong bluecollar culture, developing skills and interests

that are suitable for the cultural sector may

not be an easy task. Waitt and Gibson (2009)

argue that Wollongong, Australia, failed to

become a vibrant cultural production centre

partly because of the weight of industries such

as mining and manufacturing in the local

economy. The masculine culture prevailing

in Wollongong perceived culture as being

soft and associated with leisure and entertainment. Similarly, Middleton and Freestone

(2008), in a study of culture-led regeneration

strategies on local identity in Newcastle,

found that the local population, a significant

part of whom are blue-collar workers, lacked

interest and felt disenfranchised about them.

Thirdly, public-sector choices can be

another factor. In Canada and elsewhere,

governments and public agencies play a major

role in the cultural sector. Several industries,

such as the arts, heritage institutions, TV and

radio broadcasting as well as motion picture, video and music production are either

heavily subsidised by or organised around

public institutions. In small capital cities in

particular, government expenditures in cultural infrastructures and activities can play a

major role in the local economy (Coish, 2004;

Nelson, 2005; Petrov, 2007). Because public

cultural institutions are usually located in

capital cities, industries such as the arts and

related services and heritage institutions can

be expected to employ a higher than average

percentage of people in small cities with a

capital status. Furthermore, some small capital cities in Canada are the largest city in their

province as well as the administrative centre

(Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, is an

example). These urban areas benefit from

their central place role in cultural production,

making them the only place where cultural

production genuinely takes place in the

province. Also, the occupational structure of

capital cities is generally different from that of

non-capital cities (Carroll and Meyer, 1982).

Capital cities usually have a higher share of

professionals and service-sector workers with

higher wages and a taste for culture. By the

same token, location choices of public corporations such as the Canadian Broadcasting

Corporation (CBC-SRC) can benefit small

cities. Several small-sized urban areas are the

home of a CBC/SRC radio or television channel to serve local markets.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

CULTURAL INDUSTRIES IN CANADA 101

Fourthly, the presence of certain types

of urban and natural amenities may also

influence the location of cultural workers.

Considerable attention has been paid to

amenity-based location choices (Gibson,

2002; Florida, 2002b; Heilburn, 1996; Lewis

and Donald, 2010; Markusen and Schrock,

2006; Nelson, 2005). Although much of the

discourse on amenities in recent years is

related to the creative class theory and has

focused primarily on large metropolitan

areas, amenities are increasingly a factor

explaining location choices in small cities.

Amenity and lifestyle factors have even proven

meaningful in explaining the rapid growth of

some small Ontario towns around Toronto

(Wilkinson and Murray, 1991; Dahms and

McComb, 1999). It is argued that cultural

and creative workers prefer (and can afford)

living in attractive natural environments (i.e.

coastline and lakefront, mountain landscapes)

and in those with a small-town atmosphere

(traditional urban fabrics and vibrant downtowns). From this perspective, location in

small urban areas would be based on lifestyle

preferences rather than merely on industry

imperatives (Dahms, 1998; Gottlieb, 1994),

choices made possible by increased mobility, flexible work practices and electronic

communications (Dahms, 1998; Markusen

and Schrock, 2006; van Oort et al., 2003).

Although not all cultural workers benefit from

flexible conditions, more do than in other

industries. Many designers, artists and writers, especially those who are self-employed,

can easily produce from anywhere. Amenities,

however, can hardly be detached from proximity to large metro areas. A place may be

beautiful but will not become a desirable

residential location if remote because, as discussed earlier, proximity to large metro areas

still matters. Yet not all small towns located

around metro areas are cultural hotspots. This

is where amenities come in. Centrally located

places with amenities may therefore prove

attractive locations for a number of cultural

workers. This recalls Friedmann (1973) and

his urban field concept, an ecological unit

comprised within a 150160 km radius from

metro areas where residential settlement

takes place based on lifestyle, employment

and mobility. Within the urban field, people

seek out locations where they can both create customised residential environments and

interact with the metropolis (Dahms, 1998).

As well as attraction factors based on amenities, the lower cost of living (relative to large

metro areas) makes small places appealing to

cultural and creative workers (Dahms, 1998;

Markusen and Schrock, 2006).

Lastly, a fifth possible factor is the presence

of elderly populations which has been put

forward as a predictor for cultural consumption (Beyers, 2002; Ewoudou, 2005) and

growth in small towns and rural areas (Frey,

1993; Dahms, 1998). Elderly, and even more

so retirees, have abundant leisure time and,

often, financial resources and therefore a

greater propensity to consume given cultural

activities. Their propensity to produce given

cultural products is also greater as activities

such as the arts can be produced for both leisure and professional purposes. More flexible

(and appealing) work practices in cultural

industries have led many to extend their

professional activities beyond retirement.

Furthermore, elderly populations are more

likely to locate in non-metropolitan areas

being seldom constrained by a job location

(Frey, 1993). In addition, elderly populations

often play a central role in small town community life, including in heritage preservation

and the local art scene. However, there could

be an overlap with amenities as location

choices after retirement can also be based on

them. For instance, Elliott Lake (Ontario)

has been successful in attracting important

elderly populations in recent years because

of its natural attributes. Similarly, Port Hope,

Cobourg (Ontario) and Parksville (B.C.) have

also become the home of an important retired

community because of their amenities.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

102Jonathan Denis-Jacob

Study Area, Data and

Methodology

Study Area and Data

The study examines all Canadian urban areas

(144) with populations above 10000, classified as census metropolitan areas (CMAs)

or census agglomerations (CAs) focusing on

small cities (109) with populations below

100000. The employment data, drawn from

the 2006 census, are by the place of residence

(not place of work) and therefore account

for the number of cultural workers living in

small cities. The intended goal was to look at

the location patterns of cultural industries

in small cities; however, given the limitations

of the data available (by place of residence,

not place of work), this has not been possible and the residential location of cultural

workers was finally retained. The data are

organised around 13 cultural industries coded

at the 4-digit 1997 NAICS (North American

Industry Classification) level. Industries

were chosen over occupations in line with

a growing literature which refers to cultural

production as an industrial production system (Pratt, 1997a; Power, 2002; Evans, 2001).

In effect, cultural production does not merely

rely on artists and creative people, but also on

many others who are also central to the production process (managers, technical staff and

so on). Occupations, on the other hand, are

useful to study work tasks and where specific

professional groups tend to locate, but fail to

capture fully the total employment in given

industries. Therefore, industries were chosen

over occupations because they permit one to

draw a more accurate picture of the scope of

cultural employment in small cities.

Adopting a meaningful definition is a challenge given the definitional debates surrounding cultural industries (Hesmondhalgh and

Pratt, 2005; OConnor, 1999; Pratt, 1997a,

1997b; Scott, 2004). Definitions differ between

researchers, depending on their specific aims,

and between nations using different national

industry classification systems, making consistent international definitions difficult

(Bryan et al., 2000). Only cultural industries

concerned with the transmission of signs and

symbols (Bourdieu, 1971; Hesmondhalgh

and Pratt, 2005), those which provide goods

and services whose subjective meaning is high

in comparison with their utilitarian purpose

and those for which the aesthetic content and

sign-value to the consumer are important

(Scott, 2004) are examined. In other words,

the study focuses on industries where the

creation of cultural content is central to the

value chain. Thirteen cultural industries are

selected and grouped into nine sub-sectors to

simplify the analysis (Table 1).

The classification is largely inspired by

that of Coishs (2004) study of Canadas

metropolitan culture clusters whose 17

cultural classes are based on the definition

of cultural goods and services proposed

by the Canadian Framework for Cultural

Statistics (Statistics Canada, 2004). Four

classes from Coishs (2004) definition

(printing and related support activities,

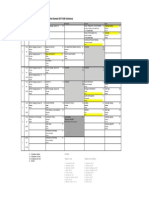

Table 1. Employment in the cultural

industries in Canadian cities, 2006

Cultural industries

Book, periodical and music

stores

Newspaper, periodical, book

and database publishers

Motion picture, video and

sound recording industries

Radio and television

broadcasting

Pay TV, specialty TV and

programme distribution

Specialised design services

Advertising and related services

The arts and related services

Heritage institutions

Total (all cultural industries)

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

Employment

in 144 cities

21010

135745

57795

38390

25975

46345

63800

33365

18925

441350

CULTURAL INDUSTRIES IN CANADA 103

manufacturing and reproducing magnetic

and optical media, information services as

well as architectural and landscape architectural services) were excluded because they

mainly include non-cultural employment.

Other business-to-business activities, such as

advertising and design, have been included

because they are mainly concerned with the

creation of value through symbolism and/

or aesthetics and because an important part

of their value chain includes creative and

cultural inputs.

The data are by place of residence, not

place of production, therefore data must be

interpreted as the location of cultural workers. Because some cultural workers may live

in a small city but work elsewhere, the data

constitute a risk if interpreted as if they related

to the place of production. This is not so much

of an issue for large metropolitan areas or

small peripheral urban areas, but can be for

small cities located near urban centres. For

that reason, the study looks at the residential

location of workers employed in cultural

industries as opposed to the distribution of

cultural production.

The data feature some limitations. First,

industrial classification systems are not

necessarily well suited to the identification

of cultural employment (Evans, 2001;

Scott, 2000). Many features of cultural

industries (part-time, contractual and freelance employment, multiple job occupancy,

multiple job locations, home-based employment and so on) are difficult to capture

adequately via industry classification systems. Furthermore, many cultural sectors

overlap with non-cultural activities, notably

advertising (with public relations activities),1

publishing (with database publishing) and

heritage institutions (with zoological and

botanical gardens and amusement parks).

Zoological and botanical gardens and amusement parks are arguably leisure activities and

more scientific than some of cultural production already broadly defined.

Methodology

Both descriptive statistics (locations quotients)

and regression models are employed to assess

the role of each factor on the strong presence

of cultural workers in small cities.2 Following

the presentation of the location quotients

(per industry and city-size class) these are

then entered as dependent variables in the

regressions. Nine regression models were built

(one for all cultural industries and one for

each cultural industry) and applied to the 109

urban areas with populations under 100000.

Descriptive Analysis: Small Cities

with Big Cultural Numbers

Figure 1 both confirms and questions the role

of city size for cultural industries. The statistical relationship between cultural employment (location quotient: all industries) is

positive, but the R2 is fairly low, leaving ample

room for other explanations.3 We can see that

some of the smallest cities exhibit a similar

(or even higher) location quotient than the

largest metro areas (Toronto, Montreal and

Vancouver). Canmore (Alberta) and Stratford

(Ontario) are the most notable cases. With a

population of about 30000, both cities exhibit

the highest location quotients in total cultural

employment with 1.65 and 1.51 respectively.

Other cities under 30000 also have relatively

high scores for their size; Port Hope, Ontario

(1.06),Whitehorse, YT (1.00), Nanaimo,

BC (0.97), Elliot Lake, Ontario (0.97) and

Yellowknife, NWT (0.95). In comparison, the

large metro areas of Quebec City and Calgary

display scores of 0.94 and 0.92 respectively.

The limited R2 (0.201) tells us that we should

look to explanations beyond city size, to which

we now turn.

In Tables 2 and 3, we employ a grouping

technique taken from Polese and Shearmur

(2004) where urban areas are grouped based

on city size and distance to the closest Top

8 census metropolitan areas (CMA).4 Four

groups of cities are created and a location

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

104Jonathan Denis-Jacob

Figure 1. Relationship between cultural specialisation and size.

Notes: Pearson correlation coefficient: 0.461 (significant at the 0.01 level); regression analysis:

R = 0.201; adjusted R2 = 0.195.

quotient is calculated for each one. Distance

is calculated with a distance matrix on the

road network using GIS. Cities are central

when within 200 km of, and peripheral when

beyond 200 km from, a Top 8 metro area.

Small cities are defined as those with a population below 100000 and the smaller cities as

those under 30000 people.

The 200 km cut-off and the population

thresholds have been determined for three

main reasons. First, a minimum number of

20 urban areas and a minimum population of

400000 per group were needed to ensure the

accuracy of the analysis. Too few observations

in each group would have given too much

weight to specific cities with extreme scores.

In addition, the 30 000 threshold permitted

a relatively even distribution between groups

of above 30000 (50 units) and below 30000

(59 units). Secondly, the 200 km cut-off

takes into account the reality of occasional

commuting and travel patterns. On the road

system, depending on driving conditions, 200

km correspond to a two-hour journey to or

from the metropolis. This distance permits

commuting to the metropolis on an irregular

basis. Thirdly, tests have been made for 150

km, 200 km, 250 km and 300 km as well as

for different sizes. The population threshold

of 30000 and the distance cut-off of 200 km

have provided the most meaningful results.

Table 3 shows that small urban areas have

higher than average location quotients in

only three sectors (heritage institutions, the

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

CULTURAL INDUSTRIES IN CANADA 105

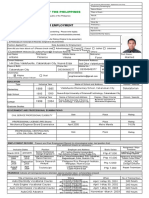

Table 2. Synthetic groups of small urban areas based on city size and distance

Synthetic regions:

urban areas

Small central

Small peripheral

Very small central

Very small peripheral

Population

threshold

Distance from

Top 8 metro (km)

Total

population

Employment

Spatial

units

100 00031000

100 00031000

Below 31000

Below 31000

Within 200

Beyond 200

Within 200

Beyond 200

1325908

1505201

418731

658625

646190

758940

205215

320935

23

27

23

36

arts and related services and radio and TV

broadcasting). Heritage institutions and the

arts and related services exhibit particularly

high LQs in central cities with a population below 30000 people. Proximity to the

metropolis provides cultural workers (and

organisations) with easy access to a diversity

of resources they may not find in a small city

(Canmore, Alberta, and Port Hope, Ontario,

are examples). On the other hand, the LQ for

employment in radio and TV broadcasting is

higher in peripheral cities with a population

below 30000. This industry, unlike PAY TV,

depends on local content, including local

news and advertisements, and therefore

requires proximity to local communities. In

contrast, employment in PAY TV is concentrated in Toronto and Montrealand almost

non-existent in small urban areasas it relies

on national subscriptions. Peripheral cities

such as Whitehorse (YT), Yellowknife (NWT)

and Rimouski (Quebec) clearly benefit from

the protection effect of distance with location

quotients of 2.3, 2.5 and 1.6 respectively.

The Regression Models

Nine regression models were built using

SPSS where the dependent variable is a location quotient per industry. The models are

performed for all 109 census agglomerations

(CAs) with populations below 100000 but

over 10000. The explanatory factors already

discussed are expressed via six independent

variables (including logged city size). The

operationalisation of these factors is the main

challenge and is discussed further.

The median housing value in 2005 is used as

a proxy for the attractiveness of a citys urban

and natural environment, therefore for the

presence of amenities. The presence of natural

amenities such as mountains, lakes and forests

or urban amenities such as a well-preserved

historical town centre and a small-town

character increasingly constitutes a powerful

predictor for high land values (Clark, 2000).

We implicitly assume that (urban and natural)

amenities are capitalised in housing values.

In Canada, unlike in the US, the quality of

Table 3. Location quotients of cultural industries, by synthetic groups of small urban areas

Cultural Sectors

All cultural industries

Books, periodical and music stores

Publishing

Motion picture, video and sound

Radio/TV broadcasting

Pay TV

Advertising and design

The arts and related services

Heritage institutions

Small

central

Small

peripheral

Very small

central

Very small

peripheral

0.56

0.88

0.60

0.36

0.42

0.68

0.50

0.56

1.01

0.55

0.72

0.73

0.38

0.75

0.51

0.37

0.40

0.80

0.70

0.69

0.79

0.38

0.52

0.53

0.44

1.07

1.63

0.54

0.94

0.59

0.41

1.16

0.47

0.29

0.40

0.97

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

106Jonathan Denis-Jacob

public services (schools, hospitals and police

forces) plays almost no role in property values

as they rarely vary in quality from one place

to another, being run and/or funded by provincial governments. Variations in property

values in small cities are most likely to be

related to the presence of specific amenities

highly sought out by residential populations.

A correlation analysis has been performed

and suggests that size and median housing

values are not correlated for urban areas

below 100000 (see Table 4). Except for a few

cases (such as Woods Buffalo, Alberta, and

Yellowknife, NWT) where property prices

are higher because of characteristics of the

local economy (the presence of natural

resources and government functions), most

other urban areas with high median housing

values are indeed known for their residential

attractiveness. Note that distance from the

Top 8 metro areas and housing values are

negatively correlated, confirming that the

residential attractiveness of small cities is

tied to proximity to large metro areas. The

logged distance in km from the nearest

Top 8 metro areas, calculated on the road

network using GIS, is used to determine

the role of location with respect to major

metro areas.

The percentage of blue-collar workers is

used to assess the effect of the so-called class

legacy on cultural employment. This variable

captures blue-collar occupations from the

National Occupational Classification (NOC-S)

2006. Occupations have been chosen over

industries to isolate blue-collar workers

from white-collar occupations in the same

industries. Some cities may have similarsized employment numbers in one industry,

but with different occupational structures

(blue collars vs managers in the pulp mill

industry, for instance). Occupations are

therefore better suited for assessing the

impact of the so-called blue-collar work

culture. Small urban areas with lower shares

of employment in blue-collar occupations

are expected to score higher than those with

high blue-collar employment numbers in

terms of cultural employment. Peripheral

urban areas would be expected to rely more

on blue-collar occupations than those near

large metropolitan areas given their dependence on natural resources. However, distance

and the percentage of blue-collar workers are

not strongly correlated (Table 5).

The percentage of population aged 65 years

and older is used as a proxy for the presence of

an important retired population. Although we

could expect some circularity between elderly

populations and amenities, the correlation

analysis confirms a weak relationship, suggesting that not all amenity-rich towns are

retirement communities.

A dummy is used as a control variable for

the four capital cities with populations below

100000 residents (Fredericton, Charlottetown,

Whitehorse, Yellowknife). A dummy variable is

used for the presence of the CBC/SRC station

in the model for radio and TV broadcasting

because it plays a central role in this industry.

Table 4. Correlation analysis on independent variables (N = 109)

Correlation coefficients

1 Total population (2006)

2 Median housing value ($)

3 CBC/SRC dummy

4 Distance (km)

5 Capital cities

6 Elderly (percentage)

7 Blue-collar workers (percentage)

1.00

0.15

-0.04

-0.07

0.09

-0.01

-0.03

0.15

1.00

-0.17

-0.28**

0.07

-0.13

-0.02

-0.04

-0.17

1.00

0.37**

0.32**

-0.29**

-0.29**

-0.07

0.09

-0.01

-0.28** 0.07

-0.13

0.37** 0.32** -0.29**

1.00

0.17

-0.26**

0.17

1.00

-0.25**

-0.26** -0.25** 1.00

-0.14

-0.36** -0.06

Note: ** significant at 0.01.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

7

-0.03

-0.02

-0.29**

-0.14

-0.36**

-0.06

1.00

CULTURAL INDUSTRIES IN CANADA 107

Table 5. Correlation between independent and dependent variables (correlations are

presented in the same order as in Table 4)

Independent variables

Dependent variable (LQ)

Total cultural employment

0.007

0.430**

Book, periodical and music

0.034

0.094

stores

Newspaper, periodical,

0.031

0.177

book and database

publishing

Motion picture, video,

-0.079

0.101

sound recording

Radio and TV broadcasting -0.149 -0.031

Pay TV, specialty TV and

0.118

0.131

programme distribution

Design and advertising

0.208* 0.388**

The arts and related services 0.010

0.315**

Heritage institutions

-0.091

0.363**

7

-0.388**

-0.251*

0.120

0.110

-0.148

0.050

0.274**

0.217*

0.197*

0.176

-0.004

-0.091

0.074

0.323** -0.195*

0.104

0.040

0.206*

0.035

0.493** 0.301** 0.260** -0.097

0.059

-0.016

0.006

0.133

-0.118

-0.020

-0.023

-0.280** 0.057

-0.237* 0.178

-0.143

0.096

0.161

0.132

-0.150

-0.180

-0.325**

-0.230*

-0.109

-0.177

-0.109

Notes: *significant at 0.05; **significant at 0.01.

Results

The results suggest relatively different R

values between industries. The most robust

models (as measured by the adjusted R2) are

those of the arts and related services (0.421),

all cultural industries (0.360), radio and TV

broadcasting (0.274) and advertising and

design (0.210). Results show that the six

variables have little effect on the location

of workers in motion picture, video and

sound recording and pay TV as they are

mainly concentrated in major metro areas

and almost non-existent in small cities.

Surprisingly, the models for heritage institutions and book, periodical and music stores

are not robust, despite high employment

numbers in small-sized urban areas. Let us

now turn to the regression coefficients for

each variable (Table 6).

Size is only significant for advertising and

design and does not appear to play a role in

any other sector. Distance with respect to large

metro areas is not significant in any model.

As discussed earlier, location with respect to

metropolitan areas may have contradictory

effects depending on the attributes of cultural

goods or services. We observed that urban

areas with similar locations (central or peripheral) exhibited quite dissimilar cultural

specialisation scores. Examples are Stratford

and Ingersoll in Ontario. Both towns lie

approximately 150 km south-west of Toronto.

The former is the second most specialised in

cultural employment, whereas the latter has

the lowest score of any urban areas. The same

holds true for peripheral cities. Whitehorse

and Yellowknife exhibit high scores in several

sectors, while Thompson (Manitoba) is at the

very bottom in all rankings. Location matters

for attracting cultural workers, but is seldom

sufficient to ensure success.

The role of elderly populations is significant

for: all cultural industries, publishing, motion

picture, video/sound recording and the arts

and related services. The findings for these

industries suggest that elderly populations

have an effect on industries characterised

by flexible specialisation, freelance employment and those which can be produced

for both leisure and professional purposes.

Retirement centres such as Elliot Lake, Port

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

108Jonathan Denis-Jacob

Table 6. Regression models: summary

Variables: Standardised coefficients

Industry

All cultural

industries

Book, periodical

and music stores

Publishing

Motion picture,

video and sound

recording

Radio and TV

broadcasting

Pay TV

Advertising and

design

The arts and

related services

Heritage

institutions

N Adjusted Log Log size Housing

R2

distance

value

107 0.360

0.012 -0.066

0.349**

105 0.045

0.134

0.177

107 0.131

107 0.092

0.011 -0.046

0.121 -0.114

0.241**

0.105

109 0.274

0.124 -0.132

0.096

0.068

Capital Percentage Percentage CBC

dummy

of blue of elderly dummy

collars

-0.287

0.334**

n.a

-0.193

0.146

n.a

0.140

0.240*

-0.129

-0.089

0.319**

0.271**

n.a

n.a

n.a

-0.187

0.062

0.419**

0.261**

-0.007

106 0.006

108 0.210

0.050

-0.144

0.026

0.201*

0.093

-0.093

0.329** 0.091

-0.255

-0.060

0.025

0.154

n.a

n.a

105 0.421

-0.008

0.016

0.349**

0.428**

-0.120

0.424**

n.a

108 0.028

-0.035 -0.025 -0.022

0.315**

0.179

0.017

n.a

Notes: Outliers have been removed from some models because of their extreme values. ** significant

at 0.01; * significant at 0.05.

Hope, Cobourg and Collingwood (Ontario)

all exhibit high scores of cultural employment. This confirms the hypothesis that

elderly populations have a greater ability to

engage in cultural industries in small cities

because of their greater liberty to live outside

metro areas.

The results suggest that small capital cities are more likely to have a higher share

of cultural employment, consistent with

expectations. Being a capital is a predictor

for all cultural industries, motion picture,

video/sound recording, the arts and related

services and heritage institutions. The presence of public cultural institutions (concert

halls, museums, art galleries) in the small

capital cities of Whitehorse, Yellowknife,

Charlottetown and Fredericton pushes up

cultural employment. Yet public expenditures in the arts and culture are not the

only reasons why these cities specialise to a

greater extent in cultural industries. These

four cities are also the central place of their

province. These urban areas exhibit high specialisation scores in the visitor-dependent

sectors (the arts and heritage institutions)

because they are often the only location

where they take place in their province

(Whitehorse, Yellowknife and Charlottetown

are examples).

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation/

Socit Radio-Canada (CBC/SRC) dummy is

the only significant one in the model for radio

and TV broadcasting, confirming its central

role in the specialisation of small peripheral

cities in this industry. It should be emphasised, however, that most urban areas with a

CBC/SRC station are central places in their

respective region. TV and radio broadcasting

is a sector which requires a certain degree of

proximity with local communities because

of local news and advertisements. Although

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

CULTURAL INDUSTRIES IN CANADA 109

production aimed at national audiences is

centralised in Toronto and Montreal for the

most part (for example, national news and

entertainment programmes), location in

peripheral urban areas is essential to ensure

local content for these communities. However,

not all peripheral central places have a CBC/

SRC station. Peripheral places such as Vernon,

BC, and Estevan, Saskatchewan, are central

places in their region but have no or little

employment in this industry. Other cities

have benefited from the location choices of

the CBC/SRC.

The class legacy explanation cannot be

rejected for cultural industries. The results

suggest that cities with high shares of employment in blue-collar occupations are less specialised in all cultural industries, radio and

TV broadcasting and pay TV. Cultural workers in general are hence less likely to locate in

places with a strong blue-collar work culture.

Canmore (Alberta), Elliot Lake (Ontario) and

Owen Sound (Ontario) are examples of places

with lower than average blue-collar occupation numbers and high cultural employment

figures. In contrast, urban areas with very

high numbers in blue-collar occupations

such as Woods Buffalo (Alberta) and Estevan

(Saskatchewan) have few cultural workers.

Surprisingly, the variable is not significant

for other core creative sectors such as the

arts and related services and motion picture,

video/sound recording. Housing value (a

proxy for amenities) is significant for all cultural industries, publishing, advertising and

design, and the arts and related services. This

confirms the footlooseness of cultural workers in given sectors and their preference for

amenity-rich environments, probably because

of their flexible work conditions and ability

to telework. This also suggests that workers

in these sectors can afford higher land values

in amenity-rich communities.

Figure 2 shows that most small urban

areas with location quotients near or above

1 also have high housing values. Cities such

as Stratford, Port Hope, Centre Wellington,

Collingwood, Cobourg and Tilsonburg are

known to be attractive places because of their

small-town atmosphere and well-preserved

urban fabric. Similarly, places like Canmore,

Nanaimo, Parksville and Owen Sound are

considered highly desirable places in which

to live because of their natural amenities. For

example, location in Collingwood, Centre

Wellington, Parksville and Port Hope has

proven suitable for design and advertising

workers (and firms) as they offer both a

pleasant place to live, work and play, and

proximity to corporate headquarters in

Vancouver and Toronto.

Workers in the arts and related services

follow a similar logic. Many small towns,

including Stratford, Cobourg (Ontario) and

Canmore (Alberta), are effectively the homes

of Canadian artists and cultural personalities.

Stratford, Ontario, is a notable example of an

amenity-rich town which continues to attract

cultural workers. The town, located half-way

between Toronto and Detroit, is famous for

its well-preserved historical town centre and

its Shakespeare Festival. With a location quotient of 6.1 in workers in the arts and related

services, the town is the most specialised of

any Canadian city. It also has above average

scores in book, periodical and music stores

and publishing. Canmore (Alberta) is another

interesting case. The town lies an hour and a

half from Calgary and is the gateway to the

Banff National park. Its beautiful natural

setting has made it one of the most desirable

residential locations in the country, especially

for those passionate about outdoor activities (skiing and hiking in particular). The

town scores high in all cultural industries,

book, periodical and music stores, publishing, the arts and heritage institutions. Wood

Buffalo (Alberta), Whitehorse (Yukon) and

Yellowknife (Northwest Territories), on the

other hand, are not amenity-based residential locations but places where property

values are driven by the local economic base

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

110Jonathan Denis-Jacob

Figure 2. Relationship between median housing value and cultural specialisation in

small cities.

Notes: Pearson correlation coefficient: 0.496 (significant at 0.01).

(dependent on government services and/or

natural resources).

Conclusion and Discussion

This paper examined the residential location

of cultural workers in small Canadian urban

areas. The results suggest that the strong presence of cultural workers is clearly not merely

a matter of size. While most cultural workers

remain concentrated in major metropolitan

areas, some small cities are also successful in

attracting them. Small places such as Stratford

(Ontario), Canmore (Alberta), Port Hope

(Ontario) and Nanaimo (BC) have indeed

a high share of their working population

employed in cultural industries. The six

explanatory factors exhibit great variability

depending on the industry. However, for

all cultural industries taken as a whole, the

presence of amenities, the absence of a bluecollar work culture and the presence of a large

elderly population are positive predictors of

large cultural worker populations in small

urban areas. Being a capital city is also an

advantage as capital cities benefit from the

presence of government cultural institutions.

The results also suggest that location in

non-metropolitan places is facilitated by the

flexible organisational and work structures

of some cultural industries. For workers

employed in industries such as publishing,

advertising and design and the arts and related

activities, location decisions appear to be

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

CULTURAL INDUSTRIES IN CANADA 111

made based on residential preferences rather

than merely on production imperatives.

Hence, the presence of (urban and natural)

amenities appears to be a selling point for

many cultural workers locating in small cities.

Moreover, elderly populations play a central

role in the cultural sector as a whole, as well

as in publishing, motion picture, video/sound

recording and the arts and related services by

being willing and able to locate outside metro

areas. Although not significant, proximity to

the metropolis remains essential to maintain

a link with a workplace, clients or/and partners, as most small cities with high scores are

located within 200 km of a Top 8 metro area.

These findings are in line with current

discussions around the rise of a residential

economy (Davezies, 2009), where location

decisions are increasingly made based on lifestyle and residential preferences made possible

by an increasingly footloose population. In

effect, the results raise several questions about

the increasingly unclear distinction between

places of work and places of residence in the

cultural economy. With such flexible and

unstable work conditions in many industries, the very notion of localised production

becomes fuzzy. While it is still obvious that

large metropolitan areas remain the main

nodes of cultural production, the rise of small

cities as sites of cultural workers residence

and, potentially, cultural production, confirms

the emergence of new forms of relationship

between work, production, leisure and living.

This, however, remains difficult to capture

with this study and therefore further quantitative and qualitative research would be needed.

The use of quantitative data by place of production would determine the extent to which

cultural production genuinely takes place

outside metro areas. In addition, qualitative

research, through interviews with cultural and

creative workers living in small cities, could

confirm the relevance of the location factors

from a personal perspective. Special attention

could also be devoted to the nature of their

professional practice (employment status,

work schedule) in order to determine whether

patterns can be identified, including between

industries. Finally, the type and frequency

of interaction with the metropolis (number

of monthly visits, clients and collaborators,

metropolitan resources sought out, etc.) could

be further investigated in order to understand

the genuine role of small cities in a growing

cultural landscape.

Notes

1. Specialised design services and advertising

and related services are also put together in

all analyses because they arguably constitute

high-order services, aiming at firms and

companies, rather than the general public.

Although their activities are different, we

argue that their nature is relatively similar in

that they require frequent contacts with and

feedback from their clients, deal mostly with

custom-made production and are concerned

with the creation of value through symbolism

and/or aesthetics.

2. The location quotient (LQ) is a measure of

specialisation of a citys share of employment

in a given industry relative to the national

average. When above 1, specialisation is higher

than the national norm, at 1 it is equal and

below 1 it is lower.

3. A regression analysis has been used to test

the relationship between size and cultural

specialisation. The natural logarithm has

been used for both city size (total population

in 2006) and cultural specialisation (LQ for

all cultural industries) to correct for the

imbalance in variable distributions.

4. The top eight metropolitan areas are Toronto,

Montreal, Vancouver, OttawaGatineau,

Calgary, Edmonton, Quebec City and Winnipeg.

References

Beyers, W. B. (2002) Culture, services and regional

development, The Service Industries Journal,

22, pp. 434.

Bourdieu, P. (1971) Le march des biens symboliques, Lanne sociologique, 22, pp. 49126.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

112Jonathan Denis-Jacob

Bryan, J., Hill, S., Munday, M. and Roberts, A.

(2000) Assessing the role of the arts and cultural industries in a local economy, Environment and Planning A, 32, pp. 13911408.

Carroll, G. and Meyer, J. (1982) Capital cities

in the American urban system: the impact of

state expansion, The American Journal of Sociology, 88, pp. 565578.

Castells, M. (1996) The Network Society. London:

Blackwell.

Christopherson, S. (2002) Project work in context: regulatory change and the new geography

of media, Environment and Planning A, 34,

pp. 20032015.

Clark, T. N. (2000) Old and new paradigms for

urban research: globalization and the fiscal

austerity and urban innovation project, Urban

Affairs Review, 36(1), pp. 345.

Clark, T. N., Lloyd, R., Wong, K. K. and Jain, P.

(2002) Amenities drive urban growth, Journal

of Urban Affairs, 24(5), pp. 493515.

Coish, D. (2004) Census metropolitan areas as

culture clusters: trends and conditions in census

metropolitan areas. Analytical paper, Culture,

Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Dahms, F. (1995) Dying villages, counterurbanization and the urban field: a Canadian perspective, Journal of Rural Studies, 11, pp. 2133.

Dahms, F. (1998) Settlement evolution in the arena society in the urban field, Journal of Rural

Studies, 14, pp. 299320.

Dahms, F. and McComb, J. (1999) Counterurbanization, interaction and functional change

in a rural amenity area: a Canadian example,

Journal of Rural Studies, 15, pp. 129146.

Davezies, L. (2009) Lconomie locale rsidentielle,

Gographie, conomie, socit, 11(1), pp. 4753.

Evans, G. (2001) Cultural Planning: An Urban

Renaissance? New York: Routledge.

Evans, G. and Foord, J. (2006) Small cities for a

small country, in: D. Bell and M. Jayne (Eds)

Small Cities: Urban Experience beyond the

Metropolis, pp. 151167. New York: Routledge.

Ewoudou, J. (2005) Understanding culture consumption in Canada. Research paper, Culture,

Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Florida, R. (2002a) Bohemia and economic geography, Journal of Economic Geography, 2, pp. 5571.

Florida, R. (2002b) The Rise of the Creative Class:

And How its Transforming Work, Leisure, and

Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books.

Florida, R. (2008) Whos Your City? How the Creative Economy is Making Where to Live the Most

Important Decision of Your Life. New York:

Basic Books.

Frey, W. H. (1993) The new urban revival in the

United States, Urban Studies, 30, pp. 741744.

Friedmann, J. (1973) The urban field as human

habitat, in: L. S. Bourne and J. W. Simmons

(Eds) Systems of Cities, pp. 4252. Toronto:

Oxford University Press.

Gibson, C. (2002) Rural transformation and cultural industries: popular music on the New

South Wales far north coast, Australian Geographical Studies, 40, pp. 337356.

Gibson, C. and Connell, J. (2004) Cultural industry production in remote places: indigenous

popular music in Australia, in: D. Power and

A. Scott (Eds) Cultural Industries and the Production of Culture, pp. 243258. New York:

Routledge.

Gottlieb, P. (1994) Amenities as an economic

development tool: is there enough evidence?,

Economic Development Quarterly, 8, pp. 270285.

Hall, P. (1998) Cities in Civilization. New York:

Pantheon.

Hall, P. (2000) Creative cities and economic

development, Urban Studies, 37, pp. 639649.

Heilburn, J. (1996) Growth, accessibility and

the distribution of arts activity in the United

States: 1980 to 1990, Journal of Cultural Economics, 20, pp. 283296.

Henderson, J. V. (1997) Medium sized cities,

Regional Science and Urban Economics, 27,

pp. 583612.

Hesmondhalgh, D. and Pratt, A. (2005) Cultural

industries and cultural policy, International

Journal of Cultural Policy, 11, pp. 113.

Hills Strategies Research Inc. (2006) Artists in

small and rural municipalities in Canada,

Statistical Insights on the Arts, 4(3) (http://

www.hillstrategies.com/resources_details.

php?resUID=1000336&lang=0).

Huber, M., Williams, A. and Shaw, G. (1992) Culture and economic policy: a survey of the role of

local authorities. Working Paper No. 5, Tourism Research Group, Department of Geography, University of Exeter.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

CULTURAL INDUSTRIES IN CANADA 113

Hutton, T. (2008) The New Economy of the Inner

City: Restructuring, Regeneration and Dislocation in the Twenty-first-century Metropolis.

New York: Routledge.

Hutton, T. (2009) Trajectories of the new economy: regeneration and dislocation in the inner

city, Urban Studies, 46, pp. 9871001.

Krugman, P. (1991) Geography and Trade. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Landry, C. (2000) The Creative City: A Toolkit for

Urban Innovators. London: Earthscan.

Lewis, N. M. and Donald, B. (2010) A new rubric

for creative city potential in Canadas smaller

cities, Urban Studies, 47, pp. 2954.

Markusen, A. and King, D. (2003) The artistic dividend: the arts hidden contributions to regional

development. Project on Regional and Industrial Economics, Humphrey Institute of Public

Affairs, University of Minnesota.

Markusen, A. and Schrock, G. (2006) The artistic dividend: urban artistic specialisation and

economic development implications, Urban

Studies, 43, pp. 16611686.

Middleton, C. and Freestone, P. (2008) The

impact of culture-led regeneration on regional

identity in north east England. Paper presented

at the Regional Studies Association International Conference: The Dilemnas of Integration and

Competition, Prague, May.

Nelson, R. (2005) A cultural hinterland? Searching for the creative class in the small Canadian

city, in: W. F. Garrett-Petts (Ed.) The Small Cities Book: On the Cultural Future of Small Cities,

pp. 85109. Vancouver: New Stars Books.

OConnor, J. (1999) The definition of cultural

industries. Manchester Institute for Popular

Culture, Manchester.

Oort, F. van, Weterings, A. and Verlinde, H.

(2003) Residential amenities of knowledge

workers and the location of ICT-firms in the

Netherlands, Tijdschrift voor Economische en

Sociale Geografie, 94(4), pp. 516523.

Petrov, A. (2007) A look beyond metropolis:

exploring creative class in the Canadian periphery, Canadian Journal of Regional Science,

30(3), pp. 451474.

Polse, M. and Champagne, E. (1999) Location

matters: comparing the distribution of economic activity in the Mexican and Canadian

urban systems, International Regional Science

Review, 22(1), pp. 102132.

Polse, M. and Shearmur, R. (2004) Is distance

really dead? Comparing industrial location

patterns over time in Canada, International

Regional Science Review, 27, pp. 431457.

Polse, M. and Shearmur, R. (2005) conomie urbaine et rgionale: introduction la Gographie

conomique, 2nd edn. Paris: Economica.

Polse, M., Rubiera-Morolln, F. and Shearmur, R.

(2005) Observing regularities in location patterns: an analysis of the spatial distribution of

economic activity in Spain. Working paper,

INRS Urbanisation Culture et socit (http://

www1.ucs.inrs.ca/pdf/inedit2005_08.pdf).

Power, D. (2002) Cultural industries in

Sweden: an assessment of their place in the

Swedish economy, Economic Geography, 78,

pp. 103127.

Pratt, A. (1997a) The cultural industries production system: a case study of employment

change in Britain, 198491, Environment and

Planning A, 29, pp. 19531974.

Pratt, A. (1997b) The cultural industries sector: its

definition and character from secondary sources

on employment and trade, Britain 198491.

Research Papers in Environmental and Spatial

Analysis No. 41, Department of Geography,

London School of Economics.

Pratt, A. (2009) Urban regeneration: from the

arts feel good factor to the cultural economy:

a case study of Hoxton, London, Urban Studies, 46, pp. 10411061.

Sassen, S. (1994) Cities in a World Economy.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge.

Scott, A. J. (1999) The US recorded music industry: on the relations between organization, location, and creativity in the cultural

economy, Environment and Planning A, 31,

pp. 19651984.

Scott, A. J. (2000) The Cultural Economy of Cities.

London: Sage.

Scott, A. J. (2004) Cultural-products industries

and urban economic development prospects

for growth and market contestation in global

context, Urban Affairs Review, 39, pp. 461490.

Sereda, P. (2007) Culture employment in a North

American context, 1981 to 2001. Research paper,

Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education

Statistics, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Shapiro, D., Abercrombie, N., Lash, S. and Lury, C.

(1992) Flexible specialisation in the culture

industries, in: H. Ernste and V. Meier (Eds)

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

114Jonathan Denis-Jacob

Regional Development and Contemporary Industrial Response: Extending Flexible Specialisation, pp. 179194. London: Belhaven.

Statistics Canada (2004) Canadian framework for

culture statistics. Culture Statistics Program,

Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, ON

(http://www.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olccel?catno=81-595-MIE2004021&lang=eng).

Statistics Canada (2005) The time it takes to get to

work and back. General Social Survey on Time

Use: Cycle 19, Social and Aboriginal Statistics

Division, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Storper, M. and Christopherson, S. (1987) Flexible specialization and regional industrial

agglomeration: the case of the U.S. motion

picture industry, Annals of the Association of

American Geographers, 77, pp. 104117.

Waitt, G. (2006) Creative small cities: cityscapes, power and the arts, in: D. Bell and

M. Jayne (Eds) Small Cities: Urban Experiences

beyond the Metropolis, pp. 169183. New York:

Routledge.

Waitt, G. and Gibson, C. (2009) Creative small

cities: rethinking the creative economy in

place, Urban Studies, 46, pp. 12231246.

Wenting, R. (2008) Spinoff dynamics and the

spatial formation of the fashion design industry, 18582005, Journal of Economic Geography, 8, pp. 593614.

Wilkinson, P. F. and Murray, A. L. (1991) Centre

and periphery: the impacts of the leisure industry on a small town (Collingwood, Ontario),

Society and Leisure, 14, pp. 235260.

Wojan, T. (2006) The emergence of rural artistic

havens: a first look. Paper presented to the Annual Meetings of the Southern Regional Science

Association, St Augustine, Florida.

Zukin, S. (1995) The Cultures of Cities. Malden,

MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on March 11, 2015

Вам также может понравиться

- Revit Architecture 2016 - Create A Curved Curtain Wall Using An In-Place Mass PDFДокумент6 страницRevit Architecture 2016 - Create A Curved Curtain Wall Using An In-Place Mass PDFIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- University of Liverpool, Incoming Handbook, Sept14-15Документ22 страницыUniversity of Liverpool, Incoming Handbook, Sept14-15Ioana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Informs: Experience The Splendour of Mediaeval GermanyДокумент62 страницыInforms: Experience The Splendour of Mediaeval GermanyIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Buero Dienstl GB PDFДокумент21 страницаBuero Dienstl GB PDFIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- DIA SS14 CalendarДокумент1 страницаDIA SS14 CalendarIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Prezentare Incuboxx 2012Документ38 страницPrezentare Incuboxx 2012Ioana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Laser Cutter RegulationsДокумент17 страницLaser Cutter RegulationsIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Schools and KindergartensДокумент40 страницSchools and KindergartensIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Aims2014 3297 PDFДокумент37 страницAims2014 3297 PDFIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- ProjectДокумент2 страницыProjectIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Collaborative WorkplaceДокумент11 страницCollaborative WorkplaceIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- DIA SS14 CalendarДокумент1 страницаDIA SS14 CalendarIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Figures A D HRДокумент1 страницаFigures A D HRIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- AR The Strategies of Mat-BuildingДокумент11 страницAR The Strategies of Mat-BuildingIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Temporary Shrinkage of Banská Štiavnica PopulationДокумент1 страницаTemporary Shrinkage of Banská Štiavnica PopulationIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Atlas Der Schrumpfenden Städte Gibt Erstmals Einen WeltweitenДокумент5 страницAtlas Der Schrumpfenden Städte Gibt Erstmals Einen WeltweitenIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Sectontoolsmanual 20110107Документ19 страницSectontoolsmanual 20110107panconlitioОценок пока нет

- Table of ContentsДокумент2 страницыTable of ContentsIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Next 7 CompetitionДокумент6 страницNext 7 CompetitionSami YakhlefОценок пока нет

- Collins Paul Noble SpanishДокумент80 страницCollins Paul Noble SpanishMustapha Rosya100% (14)

- 1st YEAR DIA - Master Architecture (Summer Semester 2014) : ElectiveДокумент1 страница1st YEAR DIA - Master Architecture (Summer Semester 2014) : ElectiveIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Table of ContentsДокумент2 страницыTable of ContentsIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- NIS Super Simple Subjunctive SpanishДокумент22 страницыNIS Super Simple Subjunctive SpanishIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Learn SpanishДокумент96 страницLearn Spanishv155r100% (64)

- DIA Schedule WS13 1006 PDFДокумент1 страницаDIA Schedule WS13 1006 PDFIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- P5 Flzekveld Final SmallДокумент75 страницP5 Flzekveld Final SmallIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Kinetics and Mechanical MotionsДокумент21 страницаKinetics and Mechanical MotionsIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Ben van Berkel Interview on Founding UNStudioДокумент17 страницBen van Berkel Interview on Founding UNStudioIoana EnglerОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Booklet Tier I I PhaseДокумент48 страницBooklet Tier I I PhaseAkhlaq HussainОценок пока нет

- Contracts Outline Burton Case Book CUA Law 2011Документ53 страницыContracts Outline Burton Case Book CUA Law 2011Robert Schafer100% (3)

- Mid Term Exam Script: MGT 729-1: Compensation ManagementДокумент11 страницMid Term Exam Script: MGT 729-1: Compensation ManagementyousufОценок пока нет

- Writing An Effective Proposal: Christopher A. BryaДокумент60 страницWriting An Effective Proposal: Christopher A. BryaAndriesPetruVladutОценок пока нет

- Ceb Physci 0 PDFДокумент15 страницCeb Physci 0 PDFPhilBoardResultsОценок пока нет

- Finance Practice ProblemsДокумент54 страницыFinance Practice ProblemsMariaОценок пока нет

- Business Letter Salutation GuideДокумент10 страницBusiness Letter Salutation GuideSartika AnggrainiОценок пока нет

- BL ICT 2300 LEC 1922S WORK IMMERSION GRADE 12 SECOND SEM Week 20 Quarterly Exam by KOYA LLOYDДокумент10 страницBL ICT 2300 LEC 1922S WORK IMMERSION GRADE 12 SECOND SEM Week 20 Quarterly Exam by KOYA LLOYDKyla Pineda67% (3)

- Culture Wars Magazine June 2012Документ52 страницыCulture Wars Magazine June 2012Hugh Beaumont100% (2)

- The Relationship Between Motivation and Organizational BehaviorДокумент3 страницыThe Relationship Between Motivation and Organizational Behavioradam100% (1)

- Green HRMДокумент6 страницGreen HRMDr.V. RohiniОценок пока нет

- Bonus Amount: 1. Contract Duration: Unlimited - The Employee Will Start Work On TBDДокумент4 страницыBonus Amount: 1. Contract Duration: Unlimited - The Employee Will Start Work On TBDConstantin EmilianОценок пока нет

- Enforcing OSH Standards and Penalizing ViolationsДокумент4 страницыEnforcing OSH Standards and Penalizing ViolationsAlbasir Tiang Sedik REEОценок пока нет

- Why Strategic Management Is So ImportantДокумент5 страницWhy Strategic Management Is So ImportantReshma AshokkumarОценок пока нет

- E-Recruitment - A New Facet of HRM: MeaningДокумент14 страницE-Recruitment - A New Facet of HRM: MeaningPreethi GowdaОценок пока нет