Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Loss of HMS Hood 1

Загружено:

Pedro Piñero CebrianАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Loss of HMS Hood 1

Загружено:

Pedro Piñero CebrianАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Loss of HMS Hood

The Loss of HMS Hood

A Re-Examination

by William J. Jurens

Part 1

Introduction:

MORE THAN HALF A CENTURY ago, the British battlecruiser HMS Hood and the German battleship

Bismarck fought what was arguably one of the most famous surface engagements of the Second World

War. In an instant on the morning of the 24th of May, 1941, the Royal Navy lost the symbolic flagship

of its fleet and the battleship Bismarck, which would have otherwise had an interesting but unremarkable

history, was transformed into one of the most well-known ships of the war. In much the same way that

the loss of the Hindenburg brought a spectacular end to the era of the airship as a credible flying

machine, the loss of the Hood marked the end of the battlecruiser as a credible fighting machine.

Since then, the story of Hood's loss and the subsequent hunt for the Bismarck has spawned at least

one popular song, a major motion picture, more than a dozen books, and innumerable accounts in the

popular literature. In spite of this, however, no complete post-war technical analysis of the loss of Hood

has ever reached print. It is the purpose of this paper to attempt to redress this omission.

Anyone approaching this event from a distance of sixty years is possessed of both advantages and

disadvantages compared to those who have gone before. Unlike the original investigators, postwar

research can provide him with comprehensive and accurate information on the ballistics and armor

penetration capabilities of German guns of the period. Unlike the original investigators, he can take

advantage of the observations of witnesses from both sides of the battle. Free of the pressure of events

and internal politics, he has the luxury of attempting a more exhaustive and objective survey than the

members of the original boards could hope to provide.

Of course there are disadvantages to this situation as well. To begin with, he is more than fifty years

distant from the events of the 24th of May 1941. He cannot call new witnesses, or, with remarkable

exceptions, recall old ones. Perhaps, most significantly, he has no "walking on" experience with the ship

herself. To the members of the original boards of inquiry, Hood was not a collection of old photographs,

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

musty engineering drawings and abstruse equations, but a concrete entity, as familiar to them as our

homes and workplaces are to us.

For a variety of reasons, the exact mechanism of the loss of Hood will probably never be known with

certainty. The event occurred with remarkable suddenness, and was to most observers completely

unexpected. No cameras were clearly trained on Hood as she exploded and no "black box" counted

down her final, fatal, seconds. There were almost no survivors and there remained virtually no

wreckage on which post-mortem might be performed. The results of past investigations - and this one must be judged with that in mind. Those charged with inquiring into more modern disasters are by

comparison usually virtually awash in a sea of data.

Chronology:

The design of HMS Hood dated back to the middle of World War I. Although the Royal Navy was

secure in the knowledge that its superiority in battleships was unassailable, the Admiralty remained

concerned about possible German superiority in battlecruisers, which if tactically well employed could

exert an influence all out of proportion to their numbers. Thus it was that Hood and her three proposed

sisters were specifically designed to counter the three fifteen-inch gunned battlecruisers which Germany

laid down in 1915 and the four more which she laid down the following year. Ironically, Hood began her

life as a fortunate survivor. Once Germany became aware of the British intent to match her battlecruiser

buildup, she abandoned battlecruiser construction to concentrate on the production of submarines and

the Admiralty correspondingly cancelled its ships as well, leaving Hood the sole survivor of an unlucky

group that would once have totaled eleven. At 41,200 tons and 860 ft 7 in [262.31 meters] overall

length, Hood was for many years the largest and most prestigious warship in the world.

The original design for Hood was approved on 7 April, 1916 and the ship laid down on 31 May. On that

very day, in what was to become the penultimate naval engagement of the First World War, three British

battlecruisers, the Indefatigable, Queen Mary and Invincible blew up under German fire at the Battle of

Jutland. "Something seems to be wrong with our bloody ships today . . .", commented a shaken British

admiral, and in fact a thorough investigation into the apparent fiasco was ordered immediately after the

battle was over. The investigators (probably incorrectly) concluded that the loss of the three

battlecruisers was the result of propellant fires reaching the magazines rather than penetrations of deck

or belt armor and thus changes to new designs and existing construction centered around improved antiflash protection rather than the provision of additional armor. Nonetheless, perceived deficiencies in the

design of Hood were considered serious enough to justify suspending work to allow a rather substantial

redesign, including a reworked armor scheme and work was not resumed until 1 September. Table I

below shows the changes made between the original and final designs. A midship section of Hood from

the text book "Practical Construction of Warships" by R.N. Newton (1939) showing her armor layout as

completed is reproduced here: Midsection (Large file - 101KB).

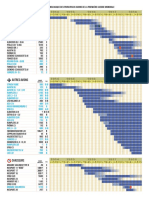

Table I

Design Parameters of HMS Hood

Original Design

of 7 April 1915

Final Design

of 30 Aug. 1917

Displacement

36,300 tons

41,200 tons

Length overall

860.0'-0" (262.13m)

860.0'-0" (262.13m)

Beam

104'-0" (31.70m)

104'-0" (31.70m)

Mean Draft

25'-6" (7.77m)

28'-6" (8.69m)

Speed

32 knots

31 knots

Upper belt

3" (76mm)

5" (127mm)

Middle belt

5" (127mm)

7" (178mm)

Lower belt

8" (203mm)

12" (305mm)

Forecastle deck

1.25" (32mm)

1.625" (41mm)

Upper deck (average)

1" (25mm)

1.25" (32mm)

Main deck (average)

1.5" (38mm)

1.875" (48mm)

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

Lower deck (average)

1.625" (41mm)

1.6" (41mm)

Average belt

5.3" (135mm)

8" (203mm)

Total Decks

5.375" (137mm)

6.35" (161mm)

Armor Weight

10,100 toms

13,550 tons

% Disp. devoted to armor

27.8%

32.8%

Inner limit Immune Zone1

31,000 yards

22,500 yards

Outer limit Immune Zone

26,200 yards

29,500 yards

Width of Immune Zone

-4,800 yards

+7,000 yards

The addition of extra armor in the final design represented a significant improvement; without it, the

immunity zone 1 against German 380mm shells would actually have been negative. Despite the addition

of some 3,450 tons of additional armor and protective plating, however, Hood was still considered

vulnerable to long range fire. Although several schemes were put forward to update her over the years,

none were ever carried out. Although as late as 1940, Jane's Fighting Ships was stating that ". . . the

general scheme of protection is most comprehensive," in Admiralty circles her actual protection was

always considered marginal. In 1920, trials with built up targets representing Hood were conducted and

showed that her magazines could be reached by a 15-in shell penetrating the 7-in [178mm] belt. In a

number of almost incredibly prophetic diagrams, the Admiralty sketched the path of the shells and

showed how the addition of 3-in [76mm] of additional deck armor could have prevented potential

disaster. 2 Two of these sketches are reproduced below.

Diagrams from C.B. 1561 "Progress in Gunnery Material - 1920" showing the results of trials on a

mockup of Hood. The simulated conditions were strikingly similar to those which finally surrounded

her loss in 1941. In spite of these trials, Hood's protective scheme was never significantly improved.

Click on this sketch for a larger view.

The Action of 24 May 1941:

Hood's final voyage began at 0050 on Thursday, 22 May, 1941, 3 as she passed Hoxa gate of Scapa

Flow in company with battleship Prince of Wales and six destroyers. Shortly thereafter, word was

received that the group would proceed to Hvals Fjord in Iceland to prevent Bismarck from attacking

convoys. As the situation developed, the group remained at sea instead, less destroyers Anthony and

Antelope, which were detached at 1400 23 May.

Hood's crew gained their first clue that something was developing at 1939, 23 May when full speed was

ordered. At 2002, a message from cruiser HMS Suffolk reported the enemy as one battleship and one

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

cruiser, course 240 degrees, in a position that translated to some 560 kilometers distant and almost

directly north of the battlecruiser force. Thirty-eight minutes later a contact report was also received

from the cruiser HMS Norfolk. Speed was increased to 26 knots at 2045 and 27 knots at 2054. Eleven

minutes later, B.C. 1 4 signaled to destroyers; "If you are unable to maintain this speed I will have to go

on without you. You should follow at your best speed." Not to be outdone by their larger counterparts,

the destroyers kept up.

Prince of Wales' narrative for Saturday the 24th, and Hood's final dawn, continues:

"Weather at 0001: Wind North, force 4-5, visibility - moderate, Sea and swells 3-4. At this

time report put the enemy 120 miles [c. 224km] 010 degs., from battlecruiser force, approx.

true course 200 degs. Speed was reduced to 25 knots at 0008 and, course altered by

blue pendant5 to 340 degs. at 0012 and 000 degs. at 0017. At 0015 ships assumed first

degree of readiness, final preparations for action were made, and battle ensign hoisted. It

was expected that contact with the enemy would be made at any time after 0140. Cruisers

at this time had lost touch with the enemy in low visibility and snow storms."

At 0031 B.C. 1 signaled "If enemy is not in sight by 0210 I will probably alter course 180 degs. until

cruisers regain touch," followed at 0032 with his plan of the action; "intend both ships to engage

'Bismarck' and to leave 'Prince Eugen' (sic) to 'Norfolk' and 'Suffolk' "6

The British went to action stations at 0015. Visibility deteriorated rapidly beginning about a half-hour

later. At 0203 Hood and Prince of Wales turned to 200 degrees and, probably in an attempt to

somewhat widen the area of search, detached their four escorting destroyers. In retrospect this seems

to have been an unfortunate decision, as they could hardly have helped but enhance the British position

at dawn. Feeling by now that the chance of an encounter before daylight was minimal, Holland gave

permission for personnel to sleep at action stations, but so tense was the atmosphere aboard the British

ships that apparently few crewmen did. Speed was increased to 26 knots at 0214 and 27 knots at 0222,

with visibility now slightly over 9,000 meters. At 0256 Suffolk regained contact with Bismarck placing the

enemy about 28,000 meters to the northwest of the battlecruiser force. Course was altered to 220

degrees at 0321 and to 240 degrees at 0342. At 0353 speed was increased to 28 knots. Bismarck was

considered to be 37,000 meters to the northwest at 0400. Visibility continued to improve, and by 0430

was about 22,000 meters.

Hood and Prince of Wales resumed first degree of readiness at 0510. There was a long wait while the

horizon became gradually more distinct and at last at 0535 Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were sighted

bearing 335 degrees on an approximate course of 240 degrees, range approximately 38,000 meters.

Hood and her consort altered course 40 degrees towards at 0537 and 20 degrees towards at 0549,

putting the British on a course of 300 degrees. Prince of Wales took station 4 cables7 distant, bearing

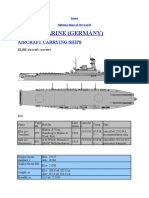

135 degrees from the flagship, i.e., on Hood's starboard quarter. The photograph below shows the

relationship between the two ships.

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

Probably one of the last photographs ever taken of H.M.S. Hood. A

photogrammetric analysis of this photo shows Hood is bearing about 341

degrees from Prince of Wales, range 975 meters (1,070 yards). "A" turret

guns of the Prince of Wales are trained on the port quarter. HU 50190.

In what was apparently a misguided attempt to close the range rapidly, or perhaps an attempt to follow

poorly conceived battle instructions, Hood and Prince of Wales gave away whatever tactical advantage

they had at initial contact by holding to their original course for far too long a time, and thereby allowing

the Germans to pass ahead.8 Having thus snookered themselves at the outset, the British ships were

forced into following a long pursuit curve while tracking the Germans, instead of maneuvering to cut

them off. As a perfect pursuit curve would require Hood and Prince of Wales to follow a continuously

curving course, and would always keep both German ships directly over the bow, in order to make

maneuvering easier and to increase their effective firepower, Holland therefore apparently ordered the

curve to be made in a series of straight segments, so arranged as to keep the arcs of their after turrets

open. It was, to say the least, far from an ideal solution. 9 Even though the British were changing

course frequently, which should have greatly hampered German fire control, their rate of bearing drift

was small and the Germans' major problem would have been compensating for changes in range.

Prince of Wales' verbatim narrative of the ensuing action reads as follows: 10

"During the approach 'Hood' made 'G.I.C.' - followed by - 'G.O.B.I.' - just before opening

fire at 0552. Range approx 25,000 yards. 'Prince of Wales' opened fire at 0553.

'Bismarck' replied with extreme accuracy on 'Hood.' 2nd or 3rd salvo straddled and fire

broke out in 'Hood' in the vicinity of the port after 4-in gun mounting. Lighter ship

engaged 'Prince of Wales.' 'Prince of Wales' opening salvo was observed over, 6th was

seen to straddle. At this time 'Prince of Wales' had five 14-in guns in action. 'Y' turret

would not bear. Fire in 'Hood' spread rapidly to the mainmast. A turn of 2 blue [indicating

a course change of 20 to port] at 0555 opened 'A' arcs at 'Prince of Wales' ninth salvo.11

'Hood' had a further 2 blue flying when, at 0600, just after 'Bismarck's fifth salvo, a huge

explosion occurred 12 between 'Hood's' after funnel and mainmast and she sank in three or

four minutes. 'Hood' had fired five or six salvos, but fall of shot was not seen, possibly

because this coincided with firing of 'Prince of Wales' guns."

Fourteen hundred fifteen officers and men of H.M.S. Hood were killed in the explosion, or died in the

water shortly thereafter.

Hundreds of eyes watched as Hood approached her end. German eyes watched her through telescopes

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

and periscopes aboard the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. British eyes watched from the cruisers many

miles away. Prince of Wales' helmsman and commanders were watching her to ensure that proper

position was maintained. And because she was flag, the signalmen aboard Prince of Wales were

watching her intently. Most importantly, the entire population of the port side of Prince of Wales, on the

disengaged side and no doubt feeling a little cheated at missing the "real action," had little else to do but

watch the giant battlecruiser perform. Here, reproduced as much as possible in the words of the

witnesses themselves, is what they saw.

Bismarck fired four-gun salvos throughout. Her first salvo undoubtedly fell forward and slightly to

starboard of the Hood. On Hood's bridge, Midshipman Dundas saw it come down close off the

starboard bow. Petty Officer Blockley in the port foremost H.A. Director of Prince of Wales watched it

fall ". . . ahead of the Hood" and ". . . absolutely correct for range," whilst aboard Bismarck, Burkhard

Von Mllinheim-Rechberg in her after gunnery control station heard Korvettenkapitn Adalbert

Schneider, controlling Bismarck's salvos call it "short." Observers aboard Prince of Wales watched as

Hood steamed majestically through the resultant splashes. Schneider ordered a 400 meter bracket,

recording the long salvo as an "over" and judging the short salvo to be a straddle. Sub-Lieutenant John

Wormersley, control officer of Prince of Wales' port forward H.A. director saw the long salvo fall ". . . on

the port quarter of 'Hood' and over by 200 yards." 13 "After this," he said, "a fire appeared on the

'Hood's' boat deck."

Curiously, the fire had nothing to do with Bismarck's gunnery - instead it had almost certainly been

caused by a hit from Prinz Eugen who was also firing at the leading British target. Like many other

British observers, Wormersley had accidentally confused the fall of shot from Bismarck and Prinz

Eugen. From the German cruiser's bridge, her captain watched through binoculars with Commander

Busch, a German journalist, as Prinz Eugen's second salvo struck home, and listened as Commander

Jasper, the gunnery officer confirmed it. Within two minutes of opening fire, Prinz Eugen's gunners had

drawn blood.

Observer's impressions of the hit that caused the fire are mixed. From the port side of Prince of Wales

Admiral's shelter deck P.O. Lawrence Sutton observed ". . . a salvo of H.E. fall more or less in line

amidships of the 'Hood' also short. This was of smaller caliber than the other two." 14 The second salvo

from Bismarck ". . . appeared to go over," he said, "and at the same time there was a flash just before

the mainmast of the 'Hood' and there was a volume of black smoke which afterwards turned into grey . .

." 15 Lt. Cdr. Rowell, navigating officer of Prince of Wales, saw three splashes and saw the fourth shell

hit. Later, he marked the position of the hit clearly on the ship's plans - close to the P.3 Twin 4-in

Mounting about 275 station.16 Chief Petty Officer William Mockridge, who had done equipment trials of

the 4-in guns and supply arrangements in 1940, saw the fire break out and was sure it was based in

the 4-in ready use lockers, many of which were distributed in the vicinity. "I saw a very vivid flash," he

said. "It was so bright, like a magnesium flare." Although Mockridge shifted his periscope forward and

thus missed the actual explosion itself, the flame burned for at least ten seconds, he said, and ". . . was

still burning when I shifted my periscope."

The fire on the boat deck continued to burn from the time of the hit until Hood was destroyed. Its

effects evidently did not penetrate deep into the ship, as Hood's engine rooms were apparently

unaffected, and her speed remained unaltered to the end. It was, nonetheless, a substantial blaze.

Sergeant Terence Charles Brooks of the Royal Marines observed the scene through his periscope in P1

turret of Prince of Wales: "The second salvo from 'Bismarck' arrived and landed two on the starboard

side and one inboard on the 4-in gun deck. The remainder I did not see. Immediately afterwards there

was an enormous flash of flame on the 4-in gun deck starboard side aft. Just before this I had seen the

4-in guns crews clustered round the guardrail on the starboard side of the 4-in gun deck of the 'Hood.'

After the shell landed all that I could see was a mass of flame as high as the mainmast. I could see

nothing then of the 4-in gun crews . . ." 17 Boy Leonard Burchell on the P.1 Pom Pom deck, however,

could see men on the boat deck - each of whom was living the last few minutes of his life - trying to put

out the fire with hoses. 18 Lt. Cdr. Cecil Lawson, who watched through the periscope in Prince of Wales'

"A" turret emergency conning position was ". . . much impressed, . . . that dense volumes of smoke were

pouring out of the superstructure, the entire length of the boat deck."19

Leading seaman Hubert Fackrell, in communication with Hood by box light, saw it as ". . . a fire with

bright flame - it was a blue flame - and I got the impression at the time that it was a cordite fire. The

flames were very fierce and very high . . ." 20 Petty Officer Cyril Coates got the impression of ". . . a

shower of sparks on the boat deck not far abaft the after funnel about amidships, followed by one roll of

flame from the after screen which enveloped the after turrets." He watched as ". . . the screen doors

21

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

were blown off and an oily looking flame came through onto the quarterdeck." Able Seaman John

Boyle looked through the periscope of P.2 gunhouse as the fire seemed to take up all the

superstructure, with flames coming up both sides of it, 22 while A.B. Walter Marshall, also on the Pom

Pom deck, saw it as ". . . flames coming from what I thought was a fan-shaft on the port side of the

boat deck between the mainmast and 'X' turret." 23

Aboard Hood, A.B. Robert E. Tilburn was lying down - the safest position for unoccupied personnel

during action - on the boat deck on the port side just before Hood's port forward U.P. mounting and just

abreast the forward funnel. He saw the projectile hit - just one, he was certain - on the extreme port

side just at the forward edge of the aftermost U.P. mounting. "That hit us somewhere . . . ," he heard a

shipmate say. The shell was, he testified ". . . a small one, because I don't think the deck was very

thick and I think a big one would have gone through." 24 "Could you say whether this shell penetrated

the deck or not?" inquired the Investigative Board. He could not. He was, however, fairly certain that

the resultant fire was of cordite. Although he didn't know whether the petrol for the boats ". . . two or

three ten gallon drums and a big drum on a slipway," had been dumped, he thought the fire was too far

forward to have been petrol in any case. An order was given to put the fire out, he recalled, but almost

immediately countermanded because of the exploding ammunition. The explosions were fairly small, he

said, ". . . like Chinese crackers," and didn't seem to cause the fire to spread very much, at least not in

his direction. "Was the hatch for the 4-in ammunition hoist abreast the after funnel open or closed?"

asked the court. "It was shut," he said, "I had asked the officer for orders and he had told me to leave it

shut."

Ordinary Signalman Albert Edward Briggs recalled the events from Hood's compass platform, and was

able to give a word-for-word of the conversations that he heard there. 25 As the first shell hit, the

Squadron Gunnery Officer said "She has hit us on the boat deck and there is a fire in the ready use

lockers." 'Leave it until the ammunition has gone," 26 the Admiral replied. After that, he recalled that

contact to the spotting top had been lost as well. Although he never actually saw the hit, to Briggs the

hit seemed to be on the starboard side, ". . . because we all tended to fall over to starboard." On the

upper bridge, Midshipman W.J. Dundas recalled the torpedo officer, who was at the starboard after end

of the bridge, report a cordite fire on the starboard side of the boat deck. 27

Fifteen miles away, in H.M.S. Norfolk, Rear Admiral Wake-Walker, watched as the fire ". . . spread

forward until its length was greater than its height" and then begin to die down. "As it died down," he

said, "I saw her two fore turrets fire and the thought 'they may be able to get it under,' came into my

mind." 28 All around the scene of the action, other observers recalled thinking exactly the same thing.

Just then, Hood exploded.

Aboard Prince of Wales, Captain Leach had been anticipating trouble. He had just watched clinically as

a salvo ". . . appeared to cross the ship somewhere about the mainmast. In that salvo were, I think, two

shots short and one over, but it may have been the other way round. But I formed the impression at the

time that something had arrived on board 'Hood' in a position just before the main-mast and slightly to

starboard. . . . I in fact wondered what the result was going to be, and between one and two seconds

after I formed that impression an explosion took place in the 'Hood' which appeared to me to come from

very much the same position in the ship." 29 Commander George William Rowell, also on Prince of

Wales' bridge, thought two shells had hit in the fatal salvo instead of one. Although he discussed it at

length with Leach, they eventually agreed to disagree.

To most observers the explosion was an awe-inspiring event. It temporarily blinded Sergeant Brooks,

watching through his periscope. On board Prince of Wales, Signalman Alan Cutler remembered the

yeoman of the watch taking him around to the other side of the flag deck to avoid shrapnel - a needless

precaution it transpired, as evidently none arrived aboard. 30

To others it was surprisingly unspectacular. To Lt. Peter Slade and A.B. Richard Scott, who were on

the catapult deck of Prince of Wales preparing to fly off the aircraft, the explosion revealed itself as a

silent red glow reflected from the surrounding bulkheads.31 The impressions of many others were nearly

the same. Almost everyone agreed it was essentially noiseless, or at least sufficiently quiet that it was

drowned out by the sound of Prince of Wales' own guns and machinery. Esmond Knight, in the air

defense station above Prince of Wales' bridge, and who was to lose his sight in the next few minutes of

action, was later to recall ". . . I remember listening for it and thinking it would be a most tremendous

explosion, but I don't remember hearing an explosion at all." 32 David Wilson Boyd of Prince of Wales

recalled that "She went up with more of a rumble than a bang." Others described the explosion as ". . .

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

a deep, dull, roar," "a noise like squashing a match box on a bigger scale," or as similar to the sound

one might make by hitting a vent duct with a fist. Band Master 2nd Class Percy Cooper in Prince of

Wales' Port Forward H.A.C.P. below the waterline clearly recalled hearing Hood's gunfire before the

explosion, but strangely never heard the explosion itself, or felt any shock.33 Horace Jarret, a

commissioned engineer who had experienced depth charges only a few days before, was in Prince of

Wales' 'B' boiler room and also felt nothing significant. "Even now, looking back, I can think of no

effect," he would later tell the court. 34

To Able Seaman Tilburn, still lying down on Hood's boat deck, the explosion was almost unbelievably

innocuous. "Did you feel any particular blast yourself?" the court questioned. "No, Sir," he replied. The

noise ". . . was just as if the guns had fired, ". . . there was dead silence after the explosion." As he

floated in the water afterward, he noticed ". . . a lot of long steel tubes, sealed at both ends. . . .

Roughly 15 ft long and 1 ft diameter" floating about him, evidently crushing tubes from the ship's side

protection system. "Could you describe the color of these tubes?" inquired the court. "Rusty," he

replied.

On Hood's bridge, Signalman Briggs recalled "There was not a terrific explosion, but the officer of the

watch said to the Admiral that the Compass had gone and the Admiral said move over to the after

control." Hood initially ". . . listed 6-7 to starboard and shortly after that the Admiral said she listed right

over to port." "I was just flung forward on my face," he would testify, with others ". . . falling in all

directions." Briggs, Dundas and Tilburn were the only survivors from a crew that totaled fourteen

hundred eighteen.

Aboard Prince of Wales, Captain Leach saw the explosion as ". . . a very fierce upward rush of flame

the shape of a funnel, rather a thin funnel, and almost instantaneously the ship was enveloped in smoke

from one end to the other." To Rowell, the explosion was ". . . very definitely a vertical sheet of flame . .

. I might say egg-shaped." Leading Seaman Winston Littlewood, O.N., the trainer of Suffolk's Port H.A.

Director saw it as ". . . a huge orange pillar of sparks going in the air and clouds of black smoke. It was

a narrow pillar," he recalled, ". . . going up very high . . . When it reached to the top it fell over on both

sides." The explosion, he said, ". . . scintillated like stars . . . like a type of firework."35 To Petty Officer

Lawrence Sutton ". . . the starting of it was a thin column of flame because it attracted my attention the

way it shot into the air abaft the mainmast and before 'X' turret." Then ". . . a huge flash came up all

around 'Y' turret," he said, accompanied by ". . . a tremendous roar, mingled with the noise of 'Y' turret

firing."

Terence Brooks saw the fatal salvo arrive through the periscope of Prince of Wales' P.1 gun turret. "It

seemed to me that one shell went into the ship by the after funnel, and one also seemed to enter the

ship by the barbette of 'X' turret. There was an enormous flash which blinded me for a few moments. .

. . When I looked through my periscope again I was in time to see a black ball of smoke out of which I

distinctly saw a 15-in gun thrown through the air followed by what appeared to be the roof of a

turret." 36 William Westlake saw spurts of smoke coming out of five or six places just as the explosion

began. Petty Officer Frederick Albert French saw the explosion begin as a bulge in the boat deck,

between the after funnel and the mainmast. ". . . the boat deck appeared to raise in the middle [and] all

what I term cordite fumes came from underneath the ship from aft and about abreast the after funnel,"

he testified. It looked, ". . . like the crown of a cap being pushed up from below." There followed a

tremendous explosion. Hood's stern simply ceased to exist. Her bow reared up - ". . . like the spire of a

giant cathedral," a German observer would note - and within three minutes she was gone.

To Part 2

Footnotes for Part 1:

1 The immune zone may be defined as that area inside of which belt penetrations might occur, and

outside of which deck penetrations are possible. Thus a target within the immune zone was,

theoretically at least, invulnerable to penetration of the vitals, and in that sense "safe" from enemy fire.

The zones listed are approximate, and are calculated against Bismarck's 380mm armor piercing bullet at

a 90 degree target angle, using the thickest part of the belt to define the inner limit and 0.8 times the

total deck thickness to define the outer limit. Hood's actual armor scheme was so complex that the

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

computation of a regular immune zone is almost impossible. The 10 slope of the belt armor has been

taken into account.

2 The trials are described in C.B. 1561 "Progress in Gunnery Materiel - 1920," ADM 186/244 X/LO 1045

pp.82 et. seq. Progress in Gunnery Materiel - 1920 pp. 82 specifically states ". . . This addition to the

main deck of H.M.S. Hood has been made, the extra weight being balanced by the removal of the

torpedo control tower, four of the 5.5-inch guns, and all the above water torpedo tubes," but the author

was obviously speaking before the fact. The tone of the statement shows how far the planning had

progressed, however.

3 All times given are Zone -2. Most details of the preamble to the final action are taken from Prince of

Wales' "Narrative Of Operations Against Bismarck," ADM 116/4351 pp 392 et. seq.

4 This abbreviation apparently refers to Admiral Holland, then in overall tactical command of Hood and

Prince of Wales.

5 The "blue pendant" refers to the signal flag that was used in association with other flags in order to

transmit course change information. The color of the flag indicated the degree of change while the order

of flags on the halyard indicated the direction. When the flags were lowered, the course change was

executed by all ships simultaneously.

6 It is difficult to understand how he can have expected so early a contact as, according to Grenfell, the

rate of relative approach at this time was under 35 knots. Kennedy, however, states the relative rate of

closure was almost twice this figure. As the ships maneuvered, the relative rates were changing almost

minute by minute.

7 In British service, one cable was nominally considered to be equal to 100 Fathoms or 600 feet. It

follows therefore that 4 cables would equal slightly over 730 meters. Some reference books give a

British cable as 608 feet instead, but the difference is entirely negligible.

8 Grenfell discusses a number of alternative explanations for the seemingly poor British tactics. One is

that Holland was following the informal instructions of his superior Sir John Tovey, who, observing that

deflection errors were more common than range errors in target practice, suggested to many officers in

his command that an end on approach was best when closing the range rapidly was of paramount

importance and when "A" arcs would be closed in any case. A more likely explanation is that Holland

was simply following the precepts of the Royal Navy's Fighting instructions taught at the Admiralty

Tactical School between the wars, which apparently suggested just such an approach. See The

Bismarck Episode, pp. 61-64.

9 Hood's intercept course at 0553, provided the Germans did not maneuver to avoid, would have been

c. 270, with intercept about 0628, and would have given both the Germans and the British identical

target angles and problems with 'A' arcs. Had the Germans turned away before intercept the battle

would have turned into a duel of broadsides on parallel courses. Had they turned toward Hood and

Prince of Wales could have neatly crossed their 'T.' At the time of initial contact, 0535, Hood's intercept

course would have been about 268 with theoretical "collision" at 0633. Ironically, this would have

closed the range at about 870 meters per minute, whereas the actual range rate in practice was only

about 690 meters per minute, only a 25% improvement. Assuming Hood's supposed zone of excessive

deck vulnerability to be 5,000 meters wide, this means that the extra traverse time would have only been

about two minutes, roughly enough time for only two extra salvos to have been exchanged. Of course,

as subsequent events were to make clear, it would take only one well placed salvo to kill.

10 The footnote references and the explanatory material in square brackets have been added. The

times were approximate. The board received a number of track charts of the action, but as Captain

George Rowell, the navigating officer of Prince of Wales was to note with remarkable understatement,

they:

". . . were compiled on the following day from the information available. Unfortunately, the

plot where the narrative was being kept was thrown into some confusion by a large amount

of blood that was pouring down from the compass platform onto the track chart."

11 "A" arcs were said to be "open" when all main battery guns could bear on a single target forward of

the beam, else "closed."

12 ADM 116/4351 p.394. At this point in the narrative, an unknown author has neatly penned in the

word "apparently."

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

13 ADM 116/4351 p.210.

14 These were almost certainly 203mm shells from Prinz Eugen's first salvo. Other observers made

similar remarks, and particularly noted a salvo which appeared to fall roughly midway between the two

British ships.

15 ADM 116/4351 pp. 212.

16 ADM 116/4351 pp. 261. Hood's frames stations in British terminology were spaced about 640mm

(25.32 in) apart on average, so this point was about 175m (580 ft) aft of the bow, i.e., just aft of the after

fire control tower. Although Rowell was sure that it was a 15-in salvo which caused the damage, he

was almost certainly in error. As can be seen on board Exhibit "M" (see next page), in order to have hit

where Rowell indicated, the shell would have had to have passed through the fire control tower on its

way, which almost certainly would have come to the attention of those on the bridge. Rowell's location

for the hit is therefore probably in error as well.

17 ADM 116/4351 pp. 218-220.

18 ADM 116/4351 pp. 251.

19 ADM 116/4351 pp. 225. The reference to the "after screen" and "screen doors" remains mysterious

to me.

20 ADM 116/4351 pp. 234.

21 ADM 116/4351 pp. 236.

22 ADM 116/4351 pp. 237.

23 Presumably this was flame exiting from one of the large engine room exhausts located on the boat

deck between the after control tower and the break of the superstructure. There were several skylights

and ladderways in the area as well, but both of the ammunition hoists in this location would have

presumably been screened from his view. A complete deck plan of Hood's boat deck showing all

relevant detail is given in a number of places throughout the minutes of the various boards as Exhibit M

(see next page).

24 Tilburn's testimony is at ADM 116/4351 et. seq. A.B. Alfred James Priddy, in partial confirmation,

stated that "The splashes of this salvo appeared to be smaller than the first two, and two splashes of

this salvo were short," but Lt. Cdr. Rowell of Prince of Wales considered ". . . very definitely that it was

a 15-in salvo." Although the court decided to side with Lt. Cdr. Rowell, the first hit on the boat deck was

almost certainly scored by Prinz Eugen.

25 ADM 116/4351 pp. 364 et. seq.

26 The exact quote in the testimony is "Leave it until the ammunition had gone," but I have corrected

the obvious error in syntax.

27 Dundas's evidence before the first board of inquiry is summarized in ADM 116/4351 pp. 59. He was

apparently not recalled to testify before the second board.

28 ADM 116/4351 pp. 148.

29 ADM 116/4351 pp. 198.

30 Several accounts purport to describe various pieces of Hood which landed on Prince of Wales after

the explosion. Upon close examination, all were proven to be parts of Prince of Wales herself, thrown

about in various ways from shells that arrived aboard later in the action.

31 ADM 116/4351 pp. 222.

32 Kennedy, pp. 87.

33 ADM 116/4351 pp. 217. How he could be sure the last sound he heard was only gunfire, however,

escapes me.

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Loss of HMS Hood

34 ADM 116/4351 pp. 222.

35 ADM 116/4351 pp. 191.

36 ADM 4351 pp. 218 et. seq. Brooks also testified "When the second hit was obtained on the 'Hood'

the after funnel seemed to crumple over and fall away to the port-side and I saw a yellow flash come at

the same time from the barbette of 'X' ". He indicated the source of this flash as being directly under

the chase of 'X' guns at the position at which they were trained.

Send mail to editor@warship.org with questions or comments about the International Naval Research Organization

Send mail to webmaster@warship.orgattention: Webmaster with technical questions about this web site.

Copyright 2007 International Naval Research Organization

Last modified: December 18, 2007

http://www.warship.org/no21987.htm[14/02/2015 19:34:37]

Вам также может понравиться

- Battleship Warspite: detailed in the original builders' plansОт EverandBattleship Warspite: detailed in the original builders' plansОценок пока нет

- Loss of HMS Hood Part 2Документ11 страницLoss of HMS Hood Part 2Pedro Piñero CebrianОценок пока нет

- Loss of HMS Hood Part 3 PDFДокумент10 страницLoss of HMS Hood Part 3 PDFPedro Piñero CebrianОценок пока нет

- Patrol Area 14: Us Navy World War Ii Submarine Patrols to the Mariana IslandsОт EverandPatrol Area 14: Us Navy World War Ii Submarine Patrols to the Mariana IslandsОценок пока нет

- Japanese Underwater Ordnance OP 1507 PDFДокумент53 страницыJapanese Underwater Ordnance OP 1507 PDFhodhodhodsribdОценок пока нет

- Examination of Italian Projectiles 47mm AP 47mm HE 105mm HE 120mm Common 149mm HE USA 1945 PDFДокумент70 страницExamination of Italian Projectiles 47mm AP 47mm HE 105mm HE 120mm Common 149mm HE USA 1945 PDFcpt_suzukiОценок пока нет

- Ards Airfield HistoryДокумент6 страницArds Airfield HistoryWilliam TurnerОценок пока нет

- Japanese Barges in ww2Документ8 страницJapanese Barges in ww2skippygoat11100% (1)

- Armament I Single-Seaters: A Survey of TheДокумент1 страницаArmament I Single-Seaters: A Survey of Theseafire47Оценок пока нет

- Type 98 20mm Machine CannonДокумент1 страницаType 98 20mm Machine CannonWilliam MyersОценок пока нет

- Flames of War - Finnish Sturmi Army ListДокумент2 страницыFlames of War - Finnish Sturmi Army ListJ4C100% (1)

- Pb4y-2 Bow TurretДокумент3 страницыPb4y-2 Bow TurrettrojandlОценок пока нет

- Amm 3cm Mk108 Komet CannonДокумент9 страницAmm 3cm Mk108 Komet CannonenricoОценок пока нет

- IJN Minekaze, Kamikaze and Mutsuki Class DestroyersДокумент11 страницIJN Minekaze, Kamikaze and Mutsuki Class DestroyersPeterD'Rock WithJason D'Argonaut100% (2)

- Recoil Less WeaponsДокумент18 страницRecoil Less Weaponscpt_suzukiОценок пока нет

- FLIGHT, July 6, 1939. eДокумент1 страницаFLIGHT, July 6, 1939. eseafire47Оценок пока нет

- KGV Tirpitz IZДокумент12 страницKGV Tirpitz IZdunmunroОценок пока нет

- Navy List Aug 1913Документ702 страницыNavy List Aug 1913Mel Spence100% (1)

- German Exp Flak Weaps Pt2Документ55 страницGerman Exp Flak Weaps Pt2Rick GainesОценок пока нет

- Air Defense of Darwin 42-44Документ3 страницыAir Defense of Darwin 42-44Alvaro Dennis Castro GuevaraОценок пока нет

- Graf ZeppelinДокумент326 страницGraf ZeppelinSawyer AubreyОценок пока нет

- WWII Micronauts Combat Table CardsДокумент7 страницWWII Micronauts Combat Table CardsBrilar2KОценок пока нет

- Capricorn Publications - Army Wheels in Detail No15 - British Anti-Tank Guns 2-Pdr, 6-Pdr, 17-PdrДокумент48 страницCapricorn Publications - Army Wheels in Detail No15 - British Anti-Tank Guns 2-Pdr, 6-Pdr, 17-PdrNickiedeposieОценок пока нет

- Standard Type BattleshipДокумент9 страницStandard Type BattleshipDarel Boyer100% (1)

- 2nd Royal Marine Battalion War Diaries - June 1916 To April 1918Документ41 страница2nd Royal Marine Battalion War Diaries - June 1916 To April 1918Gian Pietro ChiaroОценок пока нет

- French Battleship CharlemagneДокумент6 страницFrench Battleship CharlemagnerbnaoОценок пока нет

- Japanese Battleship Haruna PDFДокумент10 страницJapanese Battleship Haruna PDFdzimmer6Оценок пока нет

- 1947 US Navy WWII 8 Inch 3 Gun Turrets 220p.Документ220 страниц1947 US Navy WWII 8 Inch 3 Gun Turrets 220p.PlainNormalGuy2Оценок пока нет

- From Bellochantuy To Berlin - The Story of A Fisherman's War - HDML 1227Документ26 страницFrom Bellochantuy To Berlin - The Story of A Fisherman's War - HDML 1227Kintyre On RecordОценок пока нет

- Coast Artillery Journal - May 1929Документ89 страницCoast Artillery Journal - May 1929CAP History LibraryОценок пока нет

- Madsen Machine Rifle Main CharacteristicsДокумент64 страницыMadsen Machine Rifle Main Characteristicsapoorva singhОценок пока нет

- Russian Battleship Sevastopol (1911)Документ5 страницRussian Battleship Sevastopol (1911)Andrea MatteuzziОценок пока нет

- Fifth Destroyer Flotilla (Royal Navy)Документ26 страницFifth Destroyer Flotilla (Royal Navy)Mel SpenceОценок пока нет

- Armor May June 1993 WebДокумент56 страницArmor May June 1993 Websupergrover6868100% (1)

- Chapter 14-Battles of The Atlantic WWIДокумент34 страницыChapter 14-Battles of The Atlantic WWIAustin Rosenberg LeeОценок пока нет

- The Chapter 2 of The Royal Air Force History.... CHP2Документ42 страницыThe Chapter 2 of The Royal Air Force History.... CHP2sithusoemoe100% (1)

- The Plane in The MiddleДокумент621 страницаThe Plane in The MiddlemuratОценок пока нет

- Good Hunting German Submarine OffensiveДокумент22 страницыGood Hunting German Submarine Offensivegladio67Оценок пока нет

- Nightfighter Solo 110911 PDFДокумент11 страницNightfighter Solo 110911 PDFPaoloViarengoОценок пока нет

- Chronologie AIRCRAFT WW1Документ2 страницыChronologie AIRCRAFT WW1KalElОценок пока нет

- Har ProdДокумент12 страницHar ProdGreenLight08Оценок пока нет

- Kagero LeafletДокумент4 страницыKagero LeafletCasemate PublishersОценок пока нет

- Navwar Catalogue PDFДокумент25 страницNavwar Catalogue PDFMel SpenceОценок пока нет

- List of Aircraft WeaponsДокумент7 страницList of Aircraft WeaponsSuriya PrakashОценок пока нет

- The AMR: Anti-Material Weapon: Steyr 15.2 MM IWS 2000 Anti-Mat ?riel Rifle (AMR)Документ3 страницыThe AMR: Anti-Material Weapon: Steyr 15.2 MM IWS 2000 Anti-Mat ?riel Rifle (AMR)ouraltn2001Оценок пока нет

- South Dakota Damage Analysis SummaryДокумент10 страницSouth Dakota Damage Analysis SummaryEdward YuОценок пока нет

- Bob FinalДокумент29 страницBob FinalTony de Souza100% (2)

- FM 23-75 37-mm Gun, M1916-1940Документ164 страницыFM 23-75 37-mm Gun, M1916-1940ferdockmОценок пока нет

- German Technical Aid To Japan3Документ88 страницGerman Technical Aid To Japan3kkfj1Оценок пока нет

- Yamato Class BattleshipДокумент16 страницYamato Class BattleshipValdomero TimoteoОценок пока нет

- Hardware Wars - 1 PDFДокумент5 страницHardware Wars - 1 PDFansweringthecalОценок пока нет

- Fairmile D MTB PDFДокумент2 страницыFairmile D MTB PDFDawnОценок пока нет

- What Were The Main Strengths and Weaknesses of The German Armed ForcesДокумент6 страницWhat Were The Main Strengths and Weaknesses of The German Armed ForcesAntony TargettОценок пока нет

- @SWWAS Revised RulesДокумент11 страниц@SWWAS Revised RulesHaggard72Оценок пока нет

- U. K. Naval Gunnery Pocket Book WWДокумент309 страницU. K. Naval Gunnery Pocket Book WWdonbeach2229Оценок пока нет

- Lee EnfieldДокумент18 страницLee EnfieldMohd Asary100% (1)

- ProjectileДокумент23 страницыProjectileFrancescoОценок пока нет

- Technical and Military Imperatives: A Radar History of World War IIДокумент579 страницTechnical and Military Imperatives: A Radar History of World War IIjimmy100% (1)

- VIKING Liferafts: Technical InformationДокумент16 страницVIKING Liferafts: Technical InformationCostel MangarОценок пока нет

- Review NotesДокумент19 страницReview Notesfracson100% (1)

- Ship Status RINAДокумент9 страницShip Status RINAJorge D. ReyesОценок пока нет

- Dynamic Positioning SystemДокумент3 страницыDynamic Positioning SystemNick ManralОценок пока нет

- Specifications Hanse 315 282413Документ2 страницыSpecifications Hanse 315 282413Vladimir Illich PinzonОценок пока нет

- Survey Report For: Cargo Ship Safety Construction Certificate (CSSC)Документ14 страницSurvey Report For: Cargo Ship Safety Construction Certificate (CSSC)tacoriandОценок пока нет

- Naval Architecture Questions PDFДокумент42 страницыNaval Architecture Questions PDFShyamshesha Giri100% (1)

- Daily Routine 1-2Документ11 страницDaily Routine 1-2Mochammad Zainuddin0% (1)

- Lesson 4-Group B - History, PassiveДокумент5 страницLesson 4-Group B - History, PassiveКоляОценок пока нет

- Russian Class Rules PDFДокумент342 страницыRussian Class Rules PDFblakasОценок пока нет

- Port Adelaide Port RulesДокумент25 страницPort Adelaide Port Rulestheodorebayu100% (1)

- Vessel Database: AIS Ship PositionsДокумент3 страницыVessel Database: AIS Ship PositionsViraj SolankiОценок пока нет

- Indian Maritime UniversityДокумент12 страницIndian Maritime UniversityMohd AkifОценок пока нет

- Projet JadeДокумент11 страницProjet JadekamenskiОценок пока нет

- HMS Victory Contents DeluxeДокумент4 страницыHMS Victory Contents DeluxeIvan KostadinovicОценок пока нет

- Laporan Kerja Praktek I - KKCTBN - Joel Herdian Seciawanto RusakДокумент36 страницLaporan Kerja Praktek I - KKCTBN - Joel Herdian Seciawanto Rusakjoel herdianОценок пока нет

- Freeboard CalculationДокумент2 страницыFreeboard Calculationnawan100% (2)

- Look - Out & HelmsmanДокумент7 страницLook - Out & Helmsmanjoeven64Оценок пока нет

- Istanbul/Turkey: Med Marine A.S. - Ereğli ShipyardДокумент1 страницаIstanbul/Turkey: Med Marine A.S. - Ereğli ShipyardGogaОценок пока нет

- Marine Accident in IndonesiafixДокумент4 страницыMarine Accident in IndonesiafixnanangОценок пока нет

- How To - Starter KitДокумент11 страницHow To - Starter Kitgiggels616Оценок пока нет

- List of Model CoursesДокумент8 страницList of Model CoursesSubir BairagiОценок пока нет

- Blizzard of Glass Book Report 1Документ3 страницыBlizzard of Glass Book Report 1api-269004789Оценок пока нет

- LB Ship Particular PDFДокумент1 страницаLB Ship Particular PDFhamim hamzahОценок пока нет

- Certificate Load Test Cargo Deck Crane: Equipment Radius (Meters) Weight Applied S.W.L ResultsДокумент1 страницаCertificate Load Test Cargo Deck Crane: Equipment Radius (Meters) Weight Applied S.W.L Resultseric arosemenaОценок пока нет

- Jabatan Laut Semenanjung Malaysia Notice To MarinersДокумент3 страницыJabatan Laut Semenanjung Malaysia Notice To MarinerstaufikОценок пока нет

- Swissco Cheetah: 36M Crew / Utility BoatДокумент2 страницыSwissco Cheetah: 36M Crew / Utility Boatwaleed yehiaОценок пока нет

- Class 1Документ36 страницClass 1Aktarojjaman MiltonОценок пока нет

- Flying Colors Rules-LightДокумент11 страницFlying Colors Rules-LightPierre Vagneur-JonesОценок пока нет

- BPV Boek SWK MachinistДокумент86 страницBPV Boek SWK MachinistKlaas WakkerОценок пока нет

- Becky Lynch: The Man: Not Your Average Average GirlОт EverandBecky Lynch: The Man: Not Your Average Average GirlРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (15)

- The Arm: Inside the Billion-Dollar Mystery of the Most Valuable Commodity in SportsОт EverandThe Arm: Inside the Billion-Dollar Mystery of the Most Valuable Commodity in SportsРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (49)

- Elevate and Dominate: 21 Ways to Win On and Off the FieldОт EverandElevate and Dominate: 21 Ways to Win On and Off the FieldРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (7)

- Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube: Chasing Fear and Finding Home in the Great White NorthОт EverandWelcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube: Chasing Fear and Finding Home in the Great White NorthРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (59)

- Bloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing DynastyОт EverandBloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing DynastyРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (8)

- Crazy for the Storm: A Memoir of SurvivalОт EverandCrazy for the Storm: A Memoir of SurvivalРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (217)

- Peak: The New Science of Athletic Performance That is Revolutionizing SportsОт EverandPeak: The New Science of Athletic Performance That is Revolutionizing SportsРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (97)

- Life Is Not an Accident: A Memoir of ReinventionОт EverandLife Is Not an Accident: A Memoir of ReinventionРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (7)

- Earnhardt Nation: The Full-Throttle Saga of NASCAR's First FamilyОт EverandEarnhardt Nation: The Full-Throttle Saga of NASCAR's First FamilyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (7)

- What Winners Won't Tell You: Lessons from a Legendary DefenderОт EverandWhat Winners Won't Tell You: Lessons from a Legendary DefenderРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (7)

- Badasses: The Legend of Snake, Foo, Dr. Death, and John Madden's Oakland RaidersОт EverandBadasses: The Legend of Snake, Foo, Dr. Death, and John Madden's Oakland RaidersРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (15)

- Survive!: Essential Skills and Tactics to Get You Out of Anywhere—AliveОт EverandSurvive!: Essential Skills and Tactics to Get You Out of Anywhere—AliveОценок пока нет

- The Perfect Mile: Three Athletes, One Goal, and Less Than Four Minutes to Achieve ItОт EverandThe Perfect Mile: Three Athletes, One Goal, and Less Than Four Minutes to Achieve ItОценок пока нет

- Can't Nothing Bring Me Down: Chasing Myself in the Race Against TimeОт EverandCan't Nothing Bring Me Down: Chasing Myself in the Race Against TimeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Patriot Reign: Bill Belichick, the Coaches, and the Players Who Built a ChampionОт EverandPatriot Reign: Bill Belichick, the Coaches, and the Players Who Built a ChampionРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (30)

- The Inside Game: Bad Calls, Strange Moves, and What Baseball Behavior Teaches Us About OurselvesОт EverandThe Inside Game: Bad Calls, Strange Moves, and What Baseball Behavior Teaches Us About OurselvesРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (7)

- The Last Dive: A Father and Son's Fatal Descent into the Ocean's DepthsОт EverandThe Last Dive: A Father and Son's Fatal Descent into the Ocean's DepthsОценок пока нет

- Strong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerОт EverandStrong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5)

- Body Confidence: Venice Nutrition's 3 Step System That Unlocks Your Body's Full PotentialОт EverandBody Confidence: Venice Nutrition's 3 Step System That Unlocks Your Body's Full PotentialРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2)

- The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human PerformanceОт EverandThe Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human PerformanceРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (194)

- Summary: Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World by David Epstein: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedОт EverandSummary: Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World by David Epstein: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (6)