Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Reflections The Outsider Within: &dquo Learning Sociological Significance Analyzed Personal Place Something

Загружено:

api-277160707Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Reflections The Outsider Within: &dquo Learning Sociological Significance Analyzed Personal Place Something

Загружено:

api-277160707Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Reflections

on

the Outsider Within

Patricia Hill Collins

University of Cincinnati

It has been some time now since I wrote &dquo;Learning From the Outsider Within: The Sociological Significance of Black Feminist

Thought.&dquo; That article emerged from my need to find appropriate language that analyzed my own personal alienation in school and workplace settings. Nothing in the literature that I consulted in the 1980s

really fit. Talk of insiders, outsiders, and marginal men came close,

but something was missing. Eventually, I chose the term outsider

within because it seemed to be an apt description of individuals like

myself who found ourselves caught between groups of unequal power.

Whether the differences in power stemmed from hierarchies of race,

or class, or gender, or, in my case, the interaction among the three,

the social location of being on the edge mattered. Over time, what

began initially as a personal search to come to terms with my own

indiuidual experiences of disempowerment within intersecting power

relations of race, gender, and social class led me to wonder whether

African American women as a group occupied a comparable collective

social location.

Much has happened since I drafted my initial arguments. On the

one hand, I have been astounded by how much the idea of the outsider within has been so well-received in areas seemingly far removed

from African American women. Thats the good news. However, on

the other hand, I now see two important challenges that currently

affect this constructs continued usefulness.

The first challenge concerns the changing meanings of the term

outsider within itself. My initial use of the term described how a social groups placement in specific, historical context of race, gender,

and class inequality might influence its point of view on the world. In

Address correspondence to Patricia Hill Collins, African American Studies, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221-0370.

Journal of Career Development, Vol. 26(l),

Fall 1999

85

Downloaded from jcd.sagepub.com at UNIV NORTH CAROLINA-CHARLOTTE on April 4, 2015

86

often redefine the term outsider within as a

on individual identity can

redirect attention away from the social hierarchies of race, class, and

gender that create outsider-within social locations in the first place.

In a climate where competitive individualism runs rampant, and

where the personal confessional parades across American television

screens via an endless stream crying women on talk shows, reducing

outsider-within relationships to questions of individual identity reso-

contrast,

current

uses

personal identity category. This emphasis

nates with

distinctly American beliefs that all social problems can be

solved by working on oneself. Taking this decontextualization of the

term outsider within to its logical conclusion means that everyone can

now claim &dquo;outsider within&dquo; identity. In this situation where universalization begets trivialization, we can now all become equals.

One way that I have aimed to address this particular challenge has

been to stress the connections among specific group histories, the diverse experiences that individuals encounter within those groups,

and any subsequent knowledge that emerges in defense of the groups

search for justice (Collins, 1998). I now use the term outsider-within

to describe social locations or border spaces occupied by groups of unequal power. Individuals claim identities as &dquo;outsiders within&dquo; by

their placement in these social locations. Thus, outsider-within identities are situational identities that are attached to specific histories

of social injustice-they are not a decontextualized identity category

divorced from historical social inequalities that can be assumed by

anyone at will. What I aim to do with this shift is refocus attention

back on the unequal power relations of race, class, and gender that

produce social locations characterized by injustice. While questions of

how individuals experience social inequality is an important topic for

investigation, it is important not to lose sight of the social structures

that generate these locations.

Refocusing attention on the power relations that create outsiderwithin locations reveals several troublesome themes. For one theme,

people in outsider-within locations do not all arrive there via the

same mechanisms. African American women, Asian Indian women,

Japanese American women, and White American women may all be

considered &dquo;outsiders within&dquo; in a given corporation, but quite different group histories got them there. When looking at &dquo;outsiders

within&dquo; whose status derives from cross-cutting systems of power,

some &dquo;outsiders within&dquo; are clearly better off than others. Hierarchy

easily reestablishes itself within a category that itself had oppositional intent on its inception. Theoretically at least, all &dquo;minorities&dquo; or

Downloaded from jcd.sagepub.com at UNIV NORTH CAROLINA-CHARLOTTE on April 4, 2015

87

college classrooms or corporate boardoutsider-within

locations.

However, not all &dquo;minorities&dquo;

occupy

traveled the same path en route to these new rooms, nor are &dquo;people

of color&dquo; interchangeable when they get there.

My efforts to examine outsider-within power relations reveals a

troubling pattern in how many individuals use the construct of outsider within in everyday conversation. Many assume an equivalency

of oppression, where claiming the identity of an &dquo;outsider within&dquo; and

invoking its initial oppositional intent becomes a shortcut through all

&dquo;people

of color&dquo; who arrive in

rooms

of the difficulties of building coalitions under such adverse conditions.

It has been an amazing thing to observe-the very category that I

created to name and thereby empower African American women can

now be used to erase the specificity of U.S. Black womens experiences. These changing meanings also install a new theoretical category that gives the illusion of inclusion, yet allows old-fashioned

power relations to reorganize themselves within the space of &dquo;outsider within&dquo; identity.

A second important challenge confronting the continued usefulness

of the outsider within construct is how these changing meanings of

the term work with current marketplace ideologies. It should come as

no surprise that, for all sorts of reasons, people who find themselves

in outsider-within locations do not necessarily produce knowledge

dedicated to fostering social justice. This is because people in outsider-within locations have varying ways of claiming &dquo;outsider

within&dquo; identities. In my writings on U.S. Black womens collective,

historical use of domestic service as an outsider-within location, I explore the progressive possibilities of outsider-within locations. The existence of a collective wisdom shared by African American women

workers, however, does not negate the heterogeneous responses by

individual U.S. Black women who found themselves doing domestic

work. Within the group, many individual responses emerged.

Given this individual variability, it becomes especially important to

stress the collective nature of outsider-within positionality, especially

in our times when marketplace ideologies have become so prominent.

Marketplace ideologies increasingly affect all aspects of life, including

actual people and ideas about people in outsider-within locations.

Outsider-within locations themselves expand and shrink not just in

relation to political advocacy by African American women and other

similarly disadvantaged groups, but in response to perceived marketplace needs. Within this context, people who claim &dquo;outsider

within&dquo; identities can become hot commodities in social institutions

Downloaded from jcd.sagepub.com at UNIV NORTH CAROLINA-CHARLOTTE on April 4, 2015

88

that want the illusion of difference without the difficult effort needed

to change actual power relations. Sadly, far too often organizations

opt for cosmetic change where retrofitting and marketing handpicked individuals as authentic &dquo;outsiders within&dquo; substitutes for substantive, organizational change. In these settings, it does not matter

which &dquo;outsider within&dquo; you get. What matters is that someone convincingly play the part.

These two challenges-the changing meanings of the term outsider

within coupled with the demands of marketplace ideologies-generate new opportunities and constraints for African American women

and others who now desegregate schools and workplaces. On the one

hand, the commodification of outsider-within status whereby African

American womens value to an organization lies solely in their ability

to market a seemingly permanent marginal status can operate to suppress Black womens empowerment. Permanently claiming an &dquo;outsider within&dquo; identity rarely results in real power because the category, by definition, requires marginality. On the other hand, using the

insights gained via outsider-within status can be a stimulus to creativity that helps both African American women and their new organizational homes. Organizations should aim to eliminate outsiderwithin locations, not by excluding the individual Black women who

raise hard questions, but by including them in new ways. More importantly, for those African American women who have gained access

to places denied their mothers, new ways of inclusion, outsider-within

and otherwise, provide new opportunities for fostering social justice.

Reference

Collins, P. H. (1998). Fighting words: Black women and the search for justice. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Downloaded from jcd.sagepub.com at UNIV NORTH CAROLINA-CHARLOTTE on April 4, 2015

Вам также может понравиться

- The Great Parent Revolt: How Parents and Grassroots Leaders Are Fighting Critical Race Theory in America's SchoolsОт EverandThe Great Parent Revolt: How Parents and Grassroots Leaders Are Fighting Critical Race Theory in America's SchoolsОценок пока нет

- Black Feminist Thought As Oppositional Knowledge PDFДокумент12 страницBlack Feminist Thought As Oppositional Knowledge PDFjudith.hefetz HefetzОценок пока нет

- American Black Women and Interpersonal Leadership Styles-SensePublishers (2014)Документ128 страницAmerican Black Women and Interpersonal Leadership Styles-SensePublishers (2014)Bhavika ReddyОценок пока нет

- Party, Cle "Bone" Sloan, References Structural Inequality When He Stated That DeindustrializationДокумент7 страницParty, Cle "Bone" Sloan, References Structural Inequality When He Stated That DeindustrializationAbraham JacqueОценок пока нет

- Silencing Gender, Age, Ethnicity and Cultural Biases in LeadershipОт EverandSilencing Gender, Age, Ethnicity and Cultural Biases in LeadershipCamilla A. MontoyaОценок пока нет

- Riot Woman: Using Feminist Values to Destroy the PatriarchyОт EverandRiot Woman: Using Feminist Values to Destroy the PatriarchyОценок пока нет

- Seeing Others: How Recognition Works—and How It Can Heal a Divided WorldОт EverandSeeing Others: How Recognition Works—and How It Can Heal a Divided WorldРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (1)

- Crime & Reason: a Black Choice: An Introduction to the Birth of Black on Black Crime and Social DysfunctionОт EverandCrime & Reason: a Black Choice: An Introduction to the Birth of Black on Black Crime and Social DysfunctionОценок пока нет

- Fordham - Fordham - Racelessness As Factor in Black Studens School SuccessДокумент32 страницыFordham - Fordham - Racelessness As Factor in Black Studens School SuccessSaul RecinasОценок пока нет

- Black Women Under State: Surveillance, Poverty & The Violence of Social AssistanceОт EverandBlack Women Under State: Surveillance, Poverty & The Violence of Social AssistanceОценок пока нет

- 1.1 Collins (1993) Toward A New VisionДокумент22 страницы1.1 Collins (1993) Toward A New Visionsteven.cwjnОценок пока нет

- XHERCIS MÉNDEZ Decolonial Feminist Movidas A Caribena Rethinks PrivilegeДокумент27 страницXHERCIS MÉNDEZ Decolonial Feminist Movidas A Caribena Rethinks PrivilegeChirley MendesОценок пока нет

- Thesis On Race Class and GenderДокумент5 страницThesis On Race Class and Gendersuejonessalem100% (2)

- Second Class: How the Elites Betrayed America's Working Men and WomenОт EverandSecond Class: How the Elites Betrayed America's Working Men and WomenОценок пока нет

- The American Anti-racist: A Teen Action Guide for Uprooting Racism and Planting Justice | Step-by-Step Skills to Recognize Racism in Schools and Communities & Dismantle Oppression Through ActivismОт EverandThe American Anti-racist: A Teen Action Guide for Uprooting Racism and Planting Justice | Step-by-Step Skills to Recognize Racism in Schools and Communities & Dismantle Oppression Through ActivismОценок пока нет

- Female Marginalization ThesisДокумент8 страницFemale Marginalization Thesisokxyghxff100% (2)

- The Social Construction of Black Feminist ThoughtДокумент30 страницThe Social Construction of Black Feminist Thoughtdocbrown85100% (2)

- Reflection Essay Sample About WritingДокумент7 страницReflection Essay Sample About Writingafibooxdjvvtdn100% (2)

- Psyc 4p71 Essay - IntersectionalityДокумент8 страницPsyc 4p71 Essay - Intersectionalityapi-534748698Оценок пока нет

- Summary of American Marxism: by Mark R. Levin - A Comprehensive SummaryОт EverandSummary of American Marxism: by Mark R. Levin - A Comprehensive SummaryОценок пока нет

- Sesion 3, Gender PerspectiveДокумент25 страницSesion 3, Gender PerspectiveDaniela GalvánОценок пока нет

- Not Your Father's Capitalism: What Race Equity Asks of U.S. Business LeadersОт EverandNot Your Father's Capitalism: What Race Equity Asks of U.S. Business LeadersОценок пока нет

- Thriving While Black: The Act of Surviving and Thriving in the same spaceОт EverandThriving While Black: The Act of Surviving and Thriving in the same spaceОценок пока нет

- Gifting Resilience: A Pandemic Study of Black Female ResistanceОт EverandGifting Resilience: A Pandemic Study of Black Female ResistanceОценок пока нет

- Identities and Inequalities Exploring The Intersections of Race Class Gender and Sexuality 3rd Edition Newman Solutions ManualДокумент5 страницIdentities and Inequalities Exploring The Intersections of Race Class Gender and Sexuality 3rd Edition Newman Solutions Manualphelimdavidklbtk100% (28)

- Identities and Inequalities Exploring The Intersections of Race Class Gender and Sexuality 3Rd Edition Newman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFДокумент26 страницIdentities and Inequalities Exploring The Intersections of Race Class Gender and Sexuality 3Rd Edition Newman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFRobertPerkinsqmjk100% (10)

- In Search of Sisterhood: Delta Sigma Theta and the Challenge of the Black Sorority MovementОт EverandIn Search of Sisterhood: Delta Sigma Theta and the Challenge of the Black Sorority MovementРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (19)

- The Progressive Reports: A Manual for the Destruction of American Values and Christian MoralityОт EverandThe Progressive Reports: A Manual for the Destruction of American Values and Christian MoralityОценок пока нет

- Bianco 15: Bracketed For Gendered LanguageДокумент14 страницBianco 15: Bracketed For Gendered LanguageJillian LilasОценок пока нет

- The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American InstitutionsОт EverandThe Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American InstitutionsРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (16)

- Research Paper Final DraftДокумент11 страницResearch Paper Final Draftapi-273175783Оценок пока нет

- Black Feminist Research PaperДокумент4 страницыBlack Feminist Research Paperwftvsutlg100% (1)

- Class: Power, Privilege, and InfluenceДокумент4 страницыClass: Power, Privilege, and InfluenceMichelle Watkins0% (1)

- On The Meaning and Necessity of A White, Anti-Racist IdentityДокумент10 страницOn The Meaning and Necessity of A White, Anti-Racist IdentityПостум БугаевОценок пока нет

- Lee - MacLean - Intersectionality Social Locations of Privilege and Conceptions of Womens OppressionДокумент14 страницLee - MacLean - Intersectionality Social Locations of Privilege and Conceptions of Womens OppressionStephanie Caroline LimaОценок пока нет

- ca1274ca-dd5a-4846-aa16-bdef6223b2a2Документ3 страницыca1274ca-dd5a-4846-aa16-bdef6223b2a2Manoj NYОценок пока нет

- White Privilege Research PaperДокумент8 страницWhite Privilege Research Paperc9k7jjfk100% (1)

- Building Resilient Organizations - The ForgeДокумент4 страницыBuilding Resilient Organizations - The ForgeivanОценок пока нет

- Curso 3 Parte IIДокумент82 страницыCurso 3 Parte IIRute De AlmeidaОценок пока нет

- Brittneydennis: BY Published 10Th August 2015 Updated 12Th April 2017Документ3 страницыBrittneydennis: BY Published 10Th August 2015 Updated 12Th April 2017Syazreen SyazreenОценок пока нет

- Theory and Practice of Writing Term PaperДокумент21 страницаTheory and Practice of Writing Term Paperapi-384336322Оценок пока нет

- The State of the Black Family: Sixty Years of Tragedies and Failures—and New Initiatives Offering HopeОт EverandThe State of the Black Family: Sixty Years of Tragedies and Failures—and New Initiatives Offering HopeОценок пока нет

- GENDER IDENTITY by JULIAN AND MENDOZAДокумент29 страницGENDER IDENTITY by JULIAN AND MENDOZACristy JulianОценок пока нет

- Mapping The Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of ColorДокумент14 страницMapping The Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of ColorROSA MARICRUZ MARTINEZ GASTOLOMENDOОценок пока нет

- Summary of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? by Beverly Daniel Tatum:And Other Conversations About Race: A Comprehensive SummaryОт EverandSummary of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? by Beverly Daniel Tatum:And Other Conversations About Race: A Comprehensive SummaryОценок пока нет

- (Type Text) : BTM7303 May Shaw Research Methods Week 6 Assignment: Build A Qualitative ProposalДокумент7 страниц(Type Text) : BTM7303 May Shaw Research Methods Week 6 Assignment: Build A Qualitative ProposalCeeCee1988Оценок пока нет

- Casas-Cortes Transatlantic TranslationsДокумент18 страницCasas-Cortes Transatlantic TranslationsMotin-drОценок пока нет

- Clinton Thesis AlinskyДокумент7 страницClinton Thesis Alinskyashleyfishererie100% (2)

- Introduction To Symposium On Toward A Feminist Theory of The Stat MACKINNON PDFДокумент11 страницIntroduction To Symposium On Toward A Feminist Theory of The Stat MACKINNON PDFFeminismo InvestigacionОценок пока нет

- Curso 3 Parte IIДокумент287 страницCurso 3 Parte IIRute De AlmeidaОценок пока нет

- Political Sociology PresentationДокумент4 страницыPolitical Sociology PresentationAtalia A. McDonaldОценок пока нет

- Beyond 'Mere Masculinity': A Trinidadian Problem ReviewДокумент11 страницBeyond 'Mere Masculinity': A Trinidadian Problem ReviewNiels SampathОценок пока нет

- Racism Research Paper PDFДокумент4 страницыRacism Research Paper PDFafeasdvym100% (1)

- Stevie Ray Vaughan Guitar Techniques Guitar TABДокумент11 страницStevie Ray Vaughan Guitar Techniques Guitar TABDanilo Borquez GonzalezОценок пока нет

- History Essay French RevolutionДокумент3 страницыHistory Essay French RevolutionWeichen Christopher XuОценок пока нет

- CAT Model FormДокумент7 страницCAT Model FormSivaji Varkala100% (1)

- 121 Arzobispo ST., Intramuros, Manila: Archdiocesan Liturgical Commission, ManilaДокумент2 страницы121 Arzobispo ST., Intramuros, Manila: Archdiocesan Liturgical Commission, ManilaJesseОценок пока нет

- Two Left Feet: What Went Wrong at Reebok India!: - Srijoy Das Archer & AngelДокумент7 страницTwo Left Feet: What Went Wrong at Reebok India!: - Srijoy Das Archer & AngelMitesh MehtaОценок пока нет

- Topic-Act of God As A General Defence: Presented To - Dr. Jaswinder Kaur Presented by - Pulkit GeraДокумент8 страницTopic-Act of God As A General Defence: Presented To - Dr. Jaswinder Kaur Presented by - Pulkit GeraPulkit GeraОценок пока нет

- Garcia Et Al v. Corinthian Colleges, Inc. - Document No. 13Документ2 страницыGarcia Et Al v. Corinthian Colleges, Inc. - Document No. 13Justia.comОценок пока нет

- LESSON 4 - COM Credo PPT-GCAS 06Документ9 страницLESSON 4 - COM Credo PPT-GCAS 06Joanne Ronquillo1-BSED-ENGОценок пока нет

- 1st Group For Cyber Law CourseДокумент18 страниц1st Group For Cyber Law Courselin linОценок пока нет

- Serenity - Cortex News FeedДокумент3 страницыSerenity - Cortex News FeedDominique Thonon100% (1)

- The Role of Counsel On Watching Brief in Criminal Prosecutions in UgandaДокумент8 страницThe Role of Counsel On Watching Brief in Criminal Prosecutions in UgandaDavid BakibingaОценок пока нет

- Recreation and Procreation: A Critical View of Sex in The Human FemaleДокумент16 страницRecreation and Procreation: A Critical View of Sex in The Human FemaleVictor MocioiuОценок пока нет

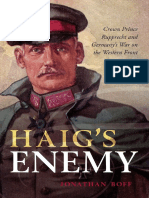

- Haig's Enemy Crown Prince Rupprecht and Germany's War On The Western FrontДокумент400 страницHaig's Enemy Crown Prince Rupprecht and Germany's War On The Western FrontZoltán VassОценок пока нет

- PDEA ComicsДокумент16 страницPDEA ComicsElla Chio Salud-MatabalaoОценок пока нет

- Updesh Kumar, Manas K. Mandal Understanding Suicide Terrorism Psychosocial DynamicsДокумент305 страницUpdesh Kumar, Manas K. Mandal Understanding Suicide Terrorism Psychosocial DynamicsfaisalnamahОценок пока нет

- Grammar Section 1 Test 1A: Present Simple Present ContinuousДокумент2 страницыGrammar Section 1 Test 1A: Present Simple Present ContinuousBodzioОценок пока нет

- Investigative Report of FindingДокумент34 страницыInvestigative Report of FindingAndrew ChammasОценок пока нет

- Zabihullah Mohmand AffidavitДокумент5 страницZabihullah Mohmand AffidavitNBC Montana0% (1)

- E and P Knowledge Organisers - All Units-2Документ8 страницE and P Knowledge Organisers - All Units-2HanaОценок пока нет

- Sri Lanka's Role in NAMДокумент7 страницSri Lanka's Role in NAMKasun JayasekaraОценок пока нет

- Media Portrayal of Mental IllnessДокумент5 страницMedia Portrayal of Mental Illnessapi-250308385Оценок пока нет

- FM 2-91.4 2008 Intelligence Support To Urban OperationsДокумент154 страницыFM 2-91.4 2008 Intelligence Support To Urban OperationsBruce JollyОценок пока нет

- Complaint BB 22Документ3 страницыComplaint BB 22Khristienne BernabeОценок пока нет

- Central Azucarera de Tarlac G.R. No. 188949Документ8 страницCentral Azucarera de Tarlac G.R. No. 188949froilanrocasОценок пока нет

- Passage 01Документ6 страницPassage 01aggarwalmeghaОценок пока нет

- Types of WritsДокумент4 страницыTypes of WritsAnuj KumarОценок пока нет

- Character Evidence NotesДокумент9 страницCharacter Evidence NotesArnoldОценок пока нет

- Fotos Proteccion Con Malla CambiosДокумент8 страницFotos Proteccion Con Malla CambiosRosemberg Reyes RamírezОценок пока нет

- Police Ethics and ValuesДокумент47 страницPolice Ethics and ValuesTerrencio Reodava100% (2)

- Income Tax (Deduction For Expenses in Relation To Secretarial Fee and Tax Filing Fee) Rules 2014 (P.U. (A) 336-2014)Документ1 страницаIncome Tax (Deduction For Expenses in Relation To Secretarial Fee and Tax Filing Fee) Rules 2014 (P.U. (A) 336-2014)Teh Chu LeongОценок пока нет