Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

When Ignorance Is No Bliss: The Influence of Maternal Education On Maternal Health Service Utilisation

Загружено:

IOSRjournalОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

When Ignorance Is No Bliss: The Influence of Maternal Education On Maternal Health Service Utilisation

Загружено:

IOSRjournalАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science (IOSR-JNHS)

e-ISSN: 23201959.p- ISSN: 23201940 Volume 4, Issue 2 Ver. III (Mar.-Apr. 2015), PP 56-61

www.iosrjournals.org

When Ignorance Is No Bliss: The Influence of Maternal education

on Maternal Health Service Utilisation

Apio Racheal1, Obiageli Crystal Oluka2, Komlan Kota2

1

Department of Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology,

13 Hangkong Road, 430030, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

2

Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science

and Technology, 13 Hangkong Road, 430030, Wuhan, Hubei, China

Abstract:

Background: Many strategies have attempted to address some of the socio-economic factors and barriers

contributing to poor maternal health service utilisation. However, utilization of maternal health services is often

influenced by several factors including womens educational status. Understanding the influence of maternal

education on maternal health service utilisation provides information for better planning and better service

utilization, and thus lead to decline in maternal mortality. The objective of this study was to highlight the

influence of maternal education on maternal health service utilisation in Uganda.

Methods: Data from the 2011 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey was used. The dependent variable was

education. Data analysis was done using SPSS for windows version 20.0. Bivariate and multivariate logistic

regression models were used in the analysis.

Results: The study results show that maternal education has a significant association with use of maternal

health services.

Conclusion: There is an undisputed strong relationship between education status of women and maternal

health service use. Government efforts and policies should be geared towards reducing the burden of the cost of

schooling, so as to increase the enrolment and retention of girls in education.

Keywords: maternal education, antenatal care, delivery care, postnatal care services

I.

Introduction

Globally, the maternal mortality ratio remains high at 289, 000maternal deaths worldwide every year;

with more than 99% of these occur in the developing world[1].The situation is more calamitous in sub-Saharan

Africa where a woman has 1 in 160 chance of dying in pregnancy or childbirth, compared to a 1 in 3,700 risk in

a developed country[2]. In Uganda, mortality is still high at 438 per 100,000 live births, with maternal deaths

accounting for 18% of all deaths to women aged 15-49[3].Maternal mortality is an issue of utmost public health

concern, especially in the developing world, in countries like Uganda, where literacy levels of women are low.

Studies have documented an association between maternal education and utilisation of maternal health

services[4], and on maternal l mortality[5].Lower levels of maternal education have been shown to be associated

with higher maternal mortality even amongst women able to access facilities providing intrapartum

care[6].Moreover, lack of education has been noted as one of a number of stressors affecting women during

pregnancy and childbirth, creating susceptibility and increasing the chance of negative outcomes[7].

Although the Ugandan government has introduced several initiatives to increase literacy levels,

including introducing the UPE (universal primary education) project aimed at providing full tuition to four

children per household ([8], with a mandate to ensure equal access by gender, the literacy levels for women are

still low (64.6%), compared with those for men (82.6%)[9].

Like most countries of the world, Uganda targets the reduction of maternal mortality by three-quarters,

by 2015 with the endorsement of the MDGs. However, maternal health service utilisation in Uganda is low;

with only48 percent of pregnant women making four or more antenatal care visits during their entire pregnancy,

only 58 percent of births being assisted by a skilled attendant and only 42 percent of these occurring in health

facilities. Post natal care is no exception, with 74 percent women who had a live birth receiving no postpartum

care at all[9].

While studies on the influence of education on maternal health service use have been extensively

documented in other countries, there is a paucity of knowledge on such studies, particularly in Uganda and SubSaharan Africa as a whole.

Using data from the 2011 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS), we examine the

relationship between maternal education and utilization of maternal health services; antenatal care, delivery care

DOI: 10.9790/1959-04235661

www.iosrjournals.org

56 | Page

When Ignorance Is No Bliss: The Influence Of Maternaleducationon Maternal

and postnatal care services. We postulate that the practices of educated women, with regard to pregnancy,

childbirth, fertility, are quite different from those of their uneducated or lesser educated counterparts.

II.

Data And Methods

Data source

This study utilized secondary data from the 2011 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS).

The data are analyzed using bivariate and multivariate analyses. The DHS is conducted every 5 years and the

2011 survey is the fifth in Uganda. In the survey, two-stage cluster sampling was used to generate a nationally

representative sample of households. The first stage involved selecting clusters from sampling frames used in

recent nationwide surveys, followed by the second stage, which selected households in each cluster.

Stratification of urban and rural areas was taken into account. The data was collected from a representative

sample of women in the reproductive age group (age 15-49) from all regions in Uganda.

Sampling procedures

A representative sample of 10,086 households was selected for the 2011 UDHS. The sample was

selected in two stages. In the first stage, 404 enumeration areas (EAs) were selected from among a list of

clusters sampled for the 2009/10 Uganda National Household Survey (2010 UNHS). An EA is a geographic

area consisting of a convenient number of dwelling units.

In the second stage of sampling, households in each cluster were selected from a complete listing of

households, which was updated prior to the survey. Households were purposively selected from those listed.

The study population for this study was all women in the reproductive age group (aged 15 to 49 years) who

delivered at least once in the last 5years preceding the survey[9].

Data collection

A structured questionnaire was used as a tool for data collection. The questionnaire was adapted from

model survey instruments developed by ICF for the MEASURE DHS project and by UNICEF for the Multiple

Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) project.

Interviewers were trained; a pretest and mock interviews were conducted before data collection in order to

ascertain the quality of data to be collected. Supervision was ensured during data collection[9].

The researcher received approval from Measure DHS to use the data, upon submission of a research proposal.

Data analysis

Analysis was done using SPSS version 20.0. Descriptive exploration of both dependent and

independent variables was first conducted. Frequencies were first determined followed by cross tabulations to

compare frequencies.

Bivariate and multivariate analysis techniques were then conducted. At bivariate level, analysis was

made by the chi square ( 2 ) test for categorical variables. The association between dependent and independent

variables was measured by means of odds ratio for which 95% confidence interval was calculated. Variables

that show a statistically significant association (p < 0.05) at bivariate level were further analyzed at multivariate

level by logistic regression. Results were accepted at the 95% Confidence level. All the variables were included

in the multivariate model once they were significantly associated at the bivariate level.

III.

Results

The results of the study are presented based on a descriptive, bivariate and multivariate logistic

regression analysis. The dependent variable was education level (coded as 0 for low, 1 for high), and the

independent variables included; contraception method, ANC (antenatal care), skilled delivery care, and PNC

(postnatal care).

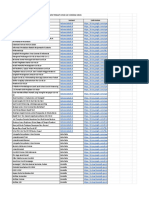

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

A total of 4,909 women aged 15 to 49 years of age who had at least one birth five years before the

survey were interviewed. Majority of the women were in the 25-29 (27.7%) and 20-24 (24.1%) age groups.

75.9% of the respondents lived in rural areas, while 24.1% lived in urban areas. 43.5% of the respondents were

Catholics, 28.1% were Protestants, and 14.0% were Muslims, 11.5% were Pentecostals, and 1.8% and 1.1%

were SDA and others, respectively. Majority (24.3%) of the respondents were from the poorest wealth quintile,

while 23.4% were in the richest wealth quintile. 47.6% of the respondents were married, while 0.7% were

divorced.

DOI: 10.9790/1959-04235661

www.iosrjournals.org

57 | Page

When Ignorance Is No Bliss: The Influence Of Maternaleducationon Maternal

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of women

Variable

Age

15-19

20-24

25-29

30-34

35-39

40-44

45-49

Residence

Urban

Rural

Religion

Catholic

Protestant

Muslim

Pentecostal

SDA

Other

Wealth index

Poorest

Poorer

Middle

Richer

Richest

Marital status

Never in union

Married

Living with partner

Widowed

Divorced

Separated

Education

Low

High

Total

(%)

375

1182

1362

871

686

325

108

7.64%

24.1%

27.7%

17.7%

14.0%

6.62%

2.20%

1185

3724

24.1%

75.9%

2136

1378

688

566

88

53

43.5%

28.1%

14.0%

11.5%

1.8%

1.1%

1193

932

841

795

1148

24.3%

19.0%

17.1%

16.2%

23.4%

216

2338

1790

118

34

409

4.40%

47.6%

36.5%

2.40%

0.7%

8.3%

3709

1200

4909

75.6%

24.4%

100%

Table 2: Logistic regression: relationship between respondents' education and factors influencing

maternal mortality

Highest education level

(

Variable

Method of contraception

No method

Traditional method

Modern method

Skilled ANC provider

No

Yes

Timing of first Antenatal checkup

0-3months

4-6months

7-9months

No.of Antenatal care visits

Less than 4

4 visits

More than 4

Skilled birth assistance

No

DOI: 10.9790/1959-04235661

2)

p-value

164.045

0.000***

11.955

0.008**

15.562

0.000***

64.913

0.000***

367.613

0.000***

www.iosrjournals.org

58 | Page

When Ignorance Is No Bliss: The Influence Of Maternaleducationon Maternal

Yes

Place of delivery

Health facility

Other

Attended Postnatal checkup

No

Yes

382.724

0.000***

251.560

0.000***

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

Logistic regression analysis showed a significant association between education and maternal health

service utilization; method of contraception, timing of first ANC checkup, number of ANC visits, skilled birth

provider, place of delivery, PNC attendancewith p-value <0.001, use of skilled ANC provider was also

significantly associated with education, p-value <0.01.

Table 3: Logistic regression: relationship between respondents education and factors influencing

maternal mortality

Variable

S.E.

Contraception

No method

-0.636 0.080

Traditional

0.222

0.188

Ref: modern method

Skilled ANC

Yes

0.563

0.155

Ref: no

Timing of ANC checkup

0-3months

0.153

0.146

4-6months

0.140

0.127

Ref: 7-9months

No.of ANC visits

Less than 4

-0.385 0.098

4 visits

-0.266 0.097

Ref: More than 4

Skilled birth assistance

No

-0.523

0.259

Ref: yes

Place of delivery

Home

-0.842 0.254

Ref: health facility

Postnatal care

No

-0.553 0.078

Ref: yes

Constant

0.040

0.156

Wald

df

Sig.

Exp(B)

95% C.I.

Lower Upper

76.306

63.612

1.396

2

1

1

0.000

0.000

0.237

0.530

1.248

0.453-0.619

0.864-1.804

13.177

0.000

1.756

1.296-2.379

1.301

1.093

1.222

2

1

1

0.522

0.296

0.269

1.165

1.151

0.875-1.553

0.897-1.475

15.799

15.452

7.448

2

1

1

0.000

0.000

0.006

0.680

0.767

0.562-0.825

0.634-0.928

4.066

0.593

0.357-0.985

10.958

0.001

0.431

0.262-0.709

50.154

0.000

0.575

0.493-0.670

0.066

0.798

1.041

0.044

The regression analysis indicated that after controlling for other covariates, method of contraception,

skilled antenatal care, number of antenatal care visits, place of delivery, birth order and postnatal care were

significantly associated with education.Women with low educationwere less likely to use modern methods of

contraception, skilled antenatal care, and postnatal care as compared to those with high education. There was

however, no significant association between skilled birth assistance and education.

IV.

Discussion

While many policies have endeavored to address the socio-economic and physical factors contributing

to poor maternal health outcomes, womens utilization of maternal health services is often influenced by several

factors including womens educational status.

In our study, maternal education had an overwhelming association with use of maternal health services.

Women with high education tended to choose health facilities for delivery more, compared to their counterparts

with lower education. This may be because better educated women are more aware of health problems, and they

use this information more effectively to sustain or attain good health status. Formal education also empowers

women to know their rights and make healthy personal choices; thereby influencing obstetric performance. This

result is in line with other studies that have highlighted the association between maternal education and

utilisation of maternal health services. Studies in Peru[10] and Guatemala[11] for example, showed that women

with primary level education were more likely to utilize maternal health services compared to those without any

DOI: 10.9790/1959-04235661

www.iosrjournals.org

59 | Page

When Ignorance Is No Bliss: The Influence Of Maternaleducationon Maternal

formal education. Mothers education was found to be an important determinant of the use of maternal health

services [12-19]. Better educated women are more aware of health problems, as well as about the availability of

health care services, and use this information more effectively to sustain or attain good health status.Education

has been shown to augment the womans knowledge of modern health-care facilities, as well as increase the

value she places on good health, resulting in heightened demand for modern health-care services[20-22].

Several studies have documented a positive and significant relationship between maternal education

and contraceptive use [23-26]. Maternal education also has a positive association with contraceptive knowledge

[26].This is because learned women are more knowledgeable as pertains to contraception, and they fully

understand the benefits of family planning. Educated women are also in better position to discuss with their

spouses on issues of contraception. A study in India showed that 95% of the women with secondary education

knew about the IUD form of contraception, while only 39% of the uneducated women had the knowledge of this

method of birth control. Maternal education affects the use of contraception through the attainment of

knowledge regarding contraception and also through increased communication between spouses. Education

affects spousal communication through increased decision-making autonomy[25]. Educated women are thus at

better liberty to discuss and choose their preferred method of contraception, as compared to women with no

education, whose decision making autonomy is usually very low, if any. Furthermore, educated women are also

more likely to use contraception consistently as soon as their desired family size has been reached. A study by

Hoqueet al[27] observed statistically significant and substantial differences in use of contraceptives between

women with different levels of education, even after controlling for other related variables. Women with no

education were thrice less likely to use contraception as compared to their learned counterparts with degrees

from colleges/universities. In a study in Dhaka, Bangladesh, the maternal education emerged as the most

significant factor influencing contraception[26].

The importance of ANC cannot be underrated; it is useful in improving pregnancy outcomes for both

the mother and the fetus. Antenatal care improves some outcomes through the detection, management of, and

referral for potential complications. ANC is used to detect early obstetric complications, counsel and motivate

women to seek appropriate care[28]. In our study, maternal education was significantly associated with use of

ANC services. The possible reason for this might be the health awareness information availed to women at ANC

visits, which bolsters the importance of using skilled care during delivery. Frequent antenatal care attendance

has an impact not only through early detection of obstetric conditions but also by influencing womens decision

to deliver babies at health facilities. This is in line with other studies that have highlighted the influence of

maternal education on ANC utilisation [29-34].

Our study is limited by possible recollection bias as participants might not fully recall events that happened

during the last 5 years preceding the survey. Furthermore, there is a possibility that the associations that we

found in our study are due to the effect of unmeasured variables that are connected with both the dependent and

independent variables in our estimated models.

V.

Conclusion

This study set out to investigate the influence of womens education status on maternal health service

utilisation. There is an undisputed strong relationship between education status of women and maternal health

service use. Government efforts and policies should be geared towards reducing the burden of the cost of

schooling, so as to increase the enrolment and retention of girls in education. The girl child should be motivated

and encouraged to pursue education; an endeavor that later pays dividends, not only to her, but to the country as

well. Government policy should aim at increasing female child enrollment in schools, so as to increase the

female literacy rate.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the general support of the Department of Health Management,

Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The authors also wish to

acknowledge Measure DHS for granting them access to the 2011 DHS dataset for Uganda.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

DOI: 10.9790/1959-04235661

www.iosrjournals.org

60 | Page

When Ignorance Is No Bliss: The Influence Of Maternaleducationon Maternal

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

Hogan, M.C., et al., Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 19802008: a systematic analysis

of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. The Lancet, 2010. 375(9726): p. 16091623.

Organisation, W.H., maternal mortality fact sheet. 2014.

Inc., U.B.o.S.U.a.I.I., Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2012.

Thaddeus S and M. D, Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Social Science and

Medicine 1994. 38(8): p. 1091-1110.

Shen C and W. JB, Maternal mortality, women's status, and economic dependency in less

developed countries: a cross-national analysis. . Social Science & Medicine 1999. 49(2): p.

197-214.

Saffron Karlsen, et al., The relationship between maternal education and mortality among

women giving birth in health care institutions: Analysis of the cross sectional WHO Global

Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. 2011.

Filippi V, et al., Maternal health in poor countries: the broader context and a call for action.

Lancet, 2006. 368: p. 1535-1541.

Sports, M.o.E.a., 1998.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). and I.I. Inc, Uganda Demographic and Health Survey

2011.Kampala, Uganda: UBOS and Calverton, Maryland: ICF International Inc. 2012.

IT, E., Utilisation of maternal health-care services in Peru: the role of women's education. .

Health Transit Rev 1992. 2: p. 49-69.

Goldman N and P. AR, Childhood immunization and pregnancy related services in Guatemala.

. Health Transit Rev 1994. 4(29-44).

Becker, S., et al., The determinants of use of maternal and child health services in Metro

Cebu, the Philippines. Health Transition Review, 1993. 3: p. 77-89.

Bhatia JC. and C. J, Determinants of maternal care in a region of South India. . Health

Transition Review, 1995. 5(127): p. 42.

Navneetham K and D. A, Utilisation of maternal health care services in Southern India. .

Social Science and Medicine 2002. 55(1849): p. 69.

Fosu, G.B., Childhood morbidity and health services utilization: cross-national comparisons of

user-related factors from DHS data. . Social Science and Medicine, 1994. 38: p. 1209-1220.

Abbas, A.A. and G.J.A. Walkern, Determinants of the utilization of maternal and child health

services in Jordan. International Journal of Epidemiology, 1986. 15: p. 404-407.

Mbacke , C. and E.v.d. Walle, Socioeconomic factors and access to health services as

determinants of child mortality. . Paper presented at IUSSP Seminar on Mortality and Society

in Sub- Saharan Africa, Yaounde, 1987.

Tekce, B. and F.C. Shorter., Determinants of child mortality: a study of squatter settlements

in Jordan. . Population and Development Review Suppl 1984. 10:: p. 257280.

Abbas, A.A. and G.J. Walker., Determinants of the utilization of maternal and child health

services in Jordan. . International Journal of Epidemiology 1986. 15:: p. 404407.

Caldwell, J., Education as a factor in mortality decline: An examination of Nigerian data. .

Population Studies 1979. 33: p. 395413.

Schultz, T.P., Studying the impact of household economic and community variables on child

mortality. Population and Development Review (Supplement) 10(215): p. 35.

Caldwell, J. and P. Caldwell., Womens position and child mortality and morbidity in LDC's. .

Research Paper. Canberra: Department of Demography, Research School of Social Sciences,

Australian National University., 1988.

United Nations. Department for Economic and Social Information and Policy Analysis, P.D.,

Women's Education and Fertility Behaviour. . New York: United Nations., 1995.

Cochrane, S.H., Fertility and Education: What do We Really Know? . The John Hopkins

University Press (For the World Bank). 1978.

DOI: 10.9790/1959-04235661

www.iosrjournals.org

61 | Page

When Ignorance Is No Bliss: The Influence Of Maternaleducationon Maternal

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

Jejeebhoy, S.J., Women's Education, Autonomy, and Reproduction Behaviour: Experience

from Developing Countries. Oxford: Clarendon Press., 1995.

Chaudhury, R.H., Female Status and Fertility Behaviour in a Metropolitan Urban Area of

Bangladesh. Population Studies. , 1978. 32(2): p. 261-273.

Hoque, M. Nazrul, and S.H. Murdock, Socioeconomic Development, Status of Women, Family

Planning and Fertility in Bangladesh. Social Biology. . 44(3-4): p. 179-197.

Yuster, E., Rethinking the role of the risk approach and antenatal care in maternal mortality

reduction. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics 1995. 50(2): p. 59-61.

Kwast BE and L. JM., Factors associated with maternal mortality in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

International Journal of Epidemiology 1988. 17(115): p. 21.

MT, H., Factors affecting the use of antenatal care in Urban Bangladesh. Urban Health Dev

Bull, 1998. 1: p. 1-4.

Monteith, R.S., et al., Use of maternal and child health services and immunization coverage

in Panama and Guatemala. PAHO Bulletin 1987. 21: p. 1-15.

Wong, E.L., et al., Accessibility, quality of care and prenatal care use in the Philippines. .

Social Science and Medicine 1987. 24:: p. 927944.

United Nation International Children Emergency Fund, P., Women's health in Pakistan. fact

sheets prepared for Pakistan National Forum on Women's Health 3-5 November, 1997: p.

16-17.

Pallikadavath S, Foss M, and S. RW, Antenatal care in rural Madhya Pradesh: provision and

inequality. 2004. 111: p. 28.

DOI: 10.9790/1959-04235661

www.iosrjournals.org

62 | Page

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Abrasive Blasting ProgramДокумент6 страницAbrasive Blasting ProgramAditya Raj MishraОценок пока нет

- Breast ReviewДокумент147 страницBreast Reviewlovelots1234100% (1)

- The Impact of Technologies On Society: A ReviewДокумент5 страницThe Impact of Technologies On Society: A ReviewInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)100% (1)

- SalphingitisДокумент25 страницSalphingitisAnonymous NDAtNJyKОценок пока нет

- Clear Aligners, A Milestone in Invisible Orthodontics - A Literature ReviewДокумент4 страницыClear Aligners, A Milestone in Invisible Orthodontics - A Literature ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- PNLEДокумент5 страницPNLEBrian100% (2)

- Work Place Law Scenario AnalysisДокумент3 страницыWork Place Law Scenario AnalysisMaria SyedОценок пока нет

- "I Am Not Gay Says A Gay Christian." A Qualitative Study On Beliefs and Prejudices of Christians Towards Homosexuality in ZimbabweДокумент5 страниц"I Am Not Gay Says A Gay Christian." A Qualitative Study On Beliefs and Prejudices of Christians Towards Homosexuality in ZimbabweInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Attitude and Perceptions of University Students in Zimbabwe Towards HomosexualityДокумент5 страницAttitude and Perceptions of University Students in Zimbabwe Towards HomosexualityInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Socio-Ethical Impact of Turkish Dramas On Educated Females of Gujranwala-PakistanДокумент7 страницSocio-Ethical Impact of Turkish Dramas On Educated Females of Gujranwala-PakistanInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- The Role of Extrovert and Introvert Personality in Second Language AcquisitionДокумент6 страницThe Role of Extrovert and Introvert Personality in Second Language AcquisitionInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- A Review of Rural Local Government System in Zimbabwe From 1980 To 2014Документ15 страницA Review of Rural Local Government System in Zimbabwe From 1980 To 2014International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- A Proposed Framework On Working With Parents of Children With Special Needs in SingaporeДокумент7 страницA Proposed Framework On Working With Parents of Children With Special Needs in SingaporeInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Social Support and Self-Esteem of Adolescent GirlsДокумент5 страницRelationship Between Social Support and Self-Esteem of Adolescent GirlsInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Assessment of The Implementation of Federal Character in Nigeria.Документ5 страницAssessment of The Implementation of Federal Character in Nigeria.International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Investigation of Unbelief and Faith in The Islam According To The Statement, Mr. Ahmed MoftizadehДокумент4 страницыInvestigation of Unbelief and Faith in The Islam According To The Statement, Mr. Ahmed MoftizadehInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Comparative Visual Analysis of Symbolic and Illegible Indus Valley Script With Other LanguagesДокумент7 страницComparative Visual Analysis of Symbolic and Illegible Indus Valley Script With Other LanguagesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- An Evaluation of Lowell's Poem "The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket" As A Pastoral ElegyДокумент14 страницAn Evaluation of Lowell's Poem "The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket" As A Pastoral ElegyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Edward Albee and His Mother Characters: An Analysis of Selected PlaysДокумент5 страницEdward Albee and His Mother Characters: An Analysis of Selected PlaysInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Importance of Mass Media in Communicating Health Messages: An AnalysisДокумент6 страницImportance of Mass Media in Communicating Health Messages: An AnalysisInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Topic: Using Wiki To Improve Students' Academic Writing in English Collaboratively: A Case Study On Undergraduate Students in BangladeshДокумент7 страницTopic: Using Wiki To Improve Students' Academic Writing in English Collaboratively: A Case Study On Undergraduate Students in BangladeshInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Role of Madarsa Education in Empowerment of Muslims in IndiaДокумент6 страницRole of Madarsa Education in Empowerment of Muslims in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Designing of Indo-Western Garments Influenced From Different Indian Classical Dance CostumesДокумент5 страницDesigning of Indo-Western Garments Influenced From Different Indian Classical Dance CostumesIOSRjournalОценок пока нет

- Johari WindowДокумент1 страницаJohari WindowPrashastiОценок пока нет

- F-08-65 Stainless Steel Alloys Eu MDR Statement On CMR and Endocrine Disrupting SubstancesДокумент3 страницыF-08-65 Stainless Steel Alloys Eu MDR Statement On CMR and Endocrine Disrupting SubstancesMubeenОценок пока нет

- Baum (2015) The New Public HealthДокумент23 страницыBaum (2015) The New Public HealthjamieОценок пока нет

- Manual, Blood CultureДокумент41 страницаManual, Blood CultureFilipus HendiantoОценок пока нет

- Cv-Update For DoctorДокумент2 страницыCv-Update For DoctorRATANRAJ SINGHDEOОценок пока нет

- Book1 PDFДокумент155 страницBook1 PDFmantoo kumarОценок пока нет

- Part Time Vs Full Time Wear of Twin Block - Parekh2019Документ8 страницPart Time Vs Full Time Wear of Twin Block - Parekh2019rohitОценок пока нет

- Q A6 - Allocated QuestionsДокумент3 страницыQ A6 - Allocated QuestionsadishsewlallОценок пока нет

- Senior Thesis 2022Документ19 страницSenior Thesis 2022api-608954316Оценок пока нет

- A Short Article About Stress (Eng-Rus)Документ2 страницыA Short Article About Stress (Eng-Rus)Егор ШульгинОценок пока нет

- Dental Drugs Prescription: Dr. Jasmine Singh Doctor BattisiДокумент15 страницDental Drugs Prescription: Dr. Jasmine Singh Doctor Battisizahra ebrahimОценок пока нет

- Badac AuditДокумент19 страницBadac AuditGeline BoreroОценок пока нет

- Penguard Primer: Technical DataДокумент3 страницыPenguard Primer: Technical DataMohamed FarhanОценок пока нет

- Ed 508483Документ187 страницEd 508483awanaernestОценок пока нет

- Kompilasi Konten Covid-19Документ50 страницKompilasi Konten Covid-19Wa UdОценок пока нет

- Water Problems Questions and Answers: 1. A Circular Well of 10 Meter Diameter With 15 Meter Depth of Water Is To BeДокумент6 страницWater Problems Questions and Answers: 1. A Circular Well of 10 Meter Diameter With 15 Meter Depth of Water Is To BeHarshitha LokeshОценок пока нет

- HR4202 ReassessmentДокумент7 страницHR4202 ReassessmentBhavya Charitha Madduri AnandaОценок пока нет

- NR527 Module 2 (Reflection 2)Документ3 страницыNR527 Module 2 (Reflection 2)96rubadiri96Оценок пока нет

- BV Healthcare Enterprises and Services 3.9.16Документ116 страницBV Healthcare Enterprises and Services 3.9.16Text81Оценок пока нет

- 07 Crash Cart Medication - (App-Pha-007-V2)Документ4 страницы07 Crash Cart Medication - (App-Pha-007-V2)سلمىОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Kapita Selekta Kelompok 3 Kapita SelektaДокумент7 страницJurnal Kapita Selekta Kelompok 3 Kapita SelektaQonita MaОценок пока нет

- Madeleine Leininger's BiographyДокумент3 страницыMadeleine Leininger's BiographyDennis Nabor Muñoz, RN,RM100% (6)

- Jurisprudance DI Questions Paper BPSC 2023 PharmapediaДокумент9 страницJurisprudance DI Questions Paper BPSC 2023 Pharmapediakrishnamahalle12Оценок пока нет

- Disaster Victim Identification (Dvi)Документ20 страницDisaster Victim Identification (Dvi)gennysuwandiОценок пока нет