Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Tbrsun B.G, Historian Mehmed The Conqueror's Time

Загружено:

fauzanrasipОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tbrsun B.G, Historian Mehmed The Conqueror's Time

Загружено:

fauzanrasipАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tbrsun B.

g, Historian of Mehmed the Conqueror's Time

Ti^t.

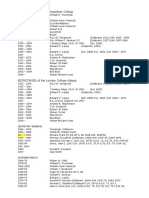

BEG,1 author of Tartkh-i Abu' I-Fath,zleft us the most detailed

andimportant accountof Mehmedthe Conqueror's time. But, surprisingly enough, his work was not known to the most famous historians

of the Ottoman Empire except for Kemal Pasha-zade;3 and very little

is known about his family.

In the course of my research on the cadi records of Bursa, I came

across some interesting information on Tursun's life and family.

These records occur between the dates Djumada II, 889 (begins on

June 26,1484) andDjumadal, 896 (begins on March 12, L491). They

show him as a partner in various legal transactions or as a witness at

some important cases.a

Tursun Beg's name is given in these records as, "Tursun Beg ibn

Harnza Beg,"s and also as "Mawlana Tursun Beg ibn tlamzaBeg."6

In his Tarlkh, Tursun mentionedDjiibbe "Ali Beg, governor of Bursa,

as his uncleT but never cited his father's name. However, we know that

Ftruz Beg was the father of HamzaBeg and "Ali Brg, Governor of

Iznik in 1422.8 Thus it becomes clear why Tursun, as a mernber of a

family which played a critically important role in Ottoman history

between the years 1380-1480, was entrusted, under Mehmed the

Conqueror, with the most important and delicate missions-as related

in his history.

Frruz Beg was one of the outstanding commanders under Murad I.

As the sandjak-beg of Ankara he took part in the battle of Konya

against "Ala d-Din the Karamanid in L387, and in the battle of

Kosovo-Polje in 1389.e Under Bayezid I he was moved to the governorship of Antalya.lo Ankara was then given to his son Ya'k[b Beg

who distinguished himself by his defense against Timur tn I4021I and

who later played a dubious part in the struggle between Mehmed I

and his brother Siileymdn. An official record in the Ankara survey

bookl2 of 867H1(begins 26.IX. 1462) proves that he had recognized

418 = Halil Inalctk

Stileymdn as Sultan in 1410. When Siileymdn had to leave for Rumeli

to go against MDsa Chelebi he enffusted Ya"kub with protecting his

Anatolian possessions.r3 Ya"kDb Beg for some time maintained an

independent position against Mehmed Chelebi (the future Mehmed

I), and did not take part in his campaign against Djtineyd Beg, of the

dynasty of Aydrn-oghullan.la On his way back Mehmed took Ankara,

captured Ya"ktb Beg and sent him to prison in Tokat (814 Wbegins

25. IV. 1411). Thus, under Mellmed I (1413-21) Firuz Beg's family,

after a long period of control in Cenrral Anatolia from Ankara, lost

some of its influence in the state. flamza, second son of Frruz B"g,

however, seems to have continued in governorship at Antalya as a

loyal man of Mehmed I.

In the struggle for the Ottoman throne against Mustafa, his uncle,

and Dji.ineyd, Murld tr followed a lenient policy toward the important

families and granted amnesty for those begs who had been involved

in actions against his father.ls Hamza and "Ah, sons of Frruz Beg,

vigorously supported the young Sultan and played an important pafi

in consolidating his sultanate, thus becoming very influential figures

during his reign.

In the summer of I422"Ah, son of FrrDz, then at Iznik (Nicaea),

successfully defended the town against the attacks of the allied forces

of Mustaf6., brother of Murad II, the Karamanids, the Germiyanids

and Isfendiyar Beg. This"Ali was apparently Djiibbe "Ah, governor of

Bursa for a long time (at least during the perio dI444-56) under Murld

II and Mehmed II. He and his son Mallmtd Beg played a central role

during the Varna crisis (1443-44).16 Evidently"Ali enjoyed the same

confidence under Mehmed II as before, and remained governor of this

key city in Anatolia. As Tursun Beg tells us17 Dji.ibbe "Ali Beg was

entrusted with the survey of Istanbul, a delicate job, in l456.It is most

probable that Djiibbe "Ali was appointed governor of Istanbul after he

carried out the survey.

The most celebrated member of the family was undoubtedly

Yamza Beg, father of our historian.l8 He was governor (subasht) of

Karahisar when he heard that his father, governor of Antalya, had died

(L421) and that Antalya was threatened by a joint attack from the begs

of Teke and Karaman.le Hamza emerged as one of the ablest military

leaders of his time when he defeated the joint attacks of the Karamanid

Mellmed Beg and the Hamid-oghlu "Ogman Chelebi in their siege of

Antalya (September L4Z2-February 1423). Upon this success he was

officially appointed governor of the sandj ak of Teke (1423). Hamza

Ttrrsun Beg, Historian of Mehmed the Conqueror's Time

4L9

was soon promoted to the governorshtp (beglerbegilik) of Anatolia

upon the death of Urudj (winter l4Z4 or spring 1425), and proved

himself to be a match for Djiineyd, the most dangerous enemy of

Ottoman rule in Anatolia. flamzaeliminatedhim and brought Smyma

and the old territory of Aydrn back under Ottoman sovereignty

(1425).20 He also played a crucial part in bringing to a successful end

the long siege of Salonica in 1430. Residing in Bursa and responsible

for Anatolian affairs, he was described as "le plus grand gouverneur

du Turcq," by Bertrandon de la Broquidre in l43Z.?1flamzabeg built

in Bursa one of the most extensive complexes of charitable institutions in the city.22In the mosque's court there are three magnificent

mausoleums: HamzaBeg's, his wife's,23 andthatof his grandsonKara

Mustafl Pasha. Tursun Beg's tomb must be one of the thirteen tombs

in the mausoleum of Harrrza Beg.

Mugtafa Pasha or Kara Mustafa Pasha, third viztr at the imperial

Divan in 1473 (after MalrmDd and Gedik A(rmed)to enjoyed the

complete confidence of Mehmed the Conqueror. He was assigned to

make inquiries about Blyezid (later Bayezid tr) in Amasya in 1477%

and to be his tutor (lala) in 1478. As tutor and then son-in-law of

Bayezid, he became the closest and most ffusted man of Bayezid tr.

As the second vizb upon Bayezld's accession he led the stn:ggle

against the dictatorial power of Gedik Alrmed; but his rivals eventually had him executed.26 The family continued, however, to hold

important positions, always in Anatolia. Mustafa Pasha' s son Mehmed

Beg was governor of the sandjalc of KhudAvendigtu by 1503 and was

married to another daughter of Bayezid II.27 Thus, along with the

Timurtash family, the Frruz Beg family held a key position in Anatolia

for over a century.

Hamza Beg's son Tursun was born to this illustrious family

apparently sometime after 1426.28 Tursun mentions in his own work,

composed after his retirement in Bursa about 1488, that he had been

in government service for forty years. He must have had madrasa

training, since he also was referred to as mawlana in the Bursa cadi

records. As a son of a beglerbegi, he must automatically have been

granted atlmdr or zi'amet wlth the title of beg in accordance with the

Ottoman regulations. However, it seems that he did not like a sipahl's

life in the countryside and "chose (instead) to join his uncle Djiibbe

'Ali Beg, governor of Bursa, to enjoy the good living in that city" (text

p. 60). In his history (p.9) he also stated that he was privileged to have

had the opportunity of working in and advancing through the ranks of

42O

= Halil Inalctk

with "wisdom and righteousness" for forty years side by

side with the great men of his age. Like the famous sixteenth century

historians Sellniki and "Ali, Tursun Beg too was a specialist in the

financial branch of the secretarial profession and served as [,]-yandjt

(provincial surveyor), Dlvan Kdtibi (Secretary in the Imperial Counstate service

ctI), Anadolu Defterdan (Financial Secretary in the province of

Anatolia), Anadolu Defter-Ketkhudasl (Keeper of the Timdr Registers in the province of Anatolia), and finally D efterdar in the Imperial

Divan in Istanbul.

Tursun B"g, as a result of hts medrese education, was equipped

with all the necessary skills and knowledge to perform the duties of

mtins hI . Reaching the rank of muns ht was the ultimate achievement in

the secretarial profession.2e In his history, Tursun Beg shows his

knowledge of Turkish, Arabic, andPersian as well as of the subtleties

of the literary arts, and his complete mastery of all the skills of a

miinshl. Furthermore, his complete familiarity with the theories and

principles of Islamic statecraft and administration is apparent from the

introduction of his his tory (text pp. 1 1 -3 1 ) . After servin g on the survey

commission for the Byzantine houses in Istanbul in 1456,30 Tursun

Beg participated in several other jobs in the provinces. Again under

Mehmed I[, Tursun Beg was involved in the survey inspection of the

yaya and milsellem troops in Anatolia in conjunction with Ishak

Chelebi, Chalab-verdi, son of Sasa Beg, and Ilyls Beg, subasht of

Kula.31 Tursun Beg was known during his time as ayandjr (secretary

or sruveyor). Since the job of provincial surveyorwas adelicate one,

surveyors were appointed frorn among the most well-known and

trustworthy people.3z

Tursun Beg's first important position in the secretarial profession

was as d,lvan katibi under the Grand Vizir Mahmtd Pasha. Tursun

states that he served under Mahmud Pasha for twelve years and that

these years made up the happiest period of his life (text p.23). Since

Mahmud Pasha's first vizirate lasted twelve years, it can be inferred

that Tursun was continuously in his service during this period. Tursun

was bound to his benefactor and patron MalrmDd Pasha by ties of great

respect. Even in his history, which was written long after Mahmtd

Pasha's death, Tursun always tries to vindicate his master's decisions

and show their wisdom. For this reason Tursun can justly be accused

of partisanship in some of his historical depictions. One example is his

description of the conquest of Agriboz (or Igriboz, Euboea), in which

he gives no recognition to RDrn Mehmed for his accomplishments,

T[rsun Beg, Historian of Mehmed the Conqueror's Time

42I

ascribing all credit for the Ottoman success in that campaign to

Mabmud Pasha (text pp. 139-a3).

Tursun Beg was lucky in writing his history in that he had the

opportunity of being present in the D tv an as secretary when important

historic decisions were made, and of witnessing important events first

hand. By virtue of his position, he was also present in the war councils

during Mahmud Pasha's campaigns and was able to record for us the

discussions and viewpoints which were debated in these councils.

(For example, see texr pp. 88, 118.) In all probability Tursun Beg

entered Mahmud Pasha's service after having completed the survey

of houses in Istanbul with his uncle in the years L456-57 .Prior to rhat

he had been in Mehmed II's army in 7452 while ir was engaged in

building the fortifications at Rumeli-Hisar and was present at the

siege of Istanbul in 1453. He was in the company of Mehmed II during

his first visit to the Aya-Sofya (Santa Sophia) after the capture of the

city and recorded verbatim in his history the Conqueror's citation of

Khaklni's famous verse on that occasion (text p. 57). In view of the

detailed information which Tursun Beg provides about the Belgrade

campaign (text pp.70-75), he probably also accompanied the sultan

on this campaign. After having entered Mahm[d Pasha's service, he

was always at the side of his master in all of the campaigns in which

he participated. we know with certainty that he was with MahmDd

during his Serbian campaign of 1458 from the important details on

that campaign contained in his history. During the Kastamoni campaign it was he, acting as Mahmtd Pasha's DIvan Katibi, who

composed the letter summoning Isma'il Beg to surrender (text pp. 9899). He was with the army in the wallachian campaign of the summer

of L462, and upon the capture of the island of Midilli (Lesbos) he was

allotted three slaves (text p. Il2) as his personal share of the booty.

Likewise in the Bosnian campaign he was with Mahm[d Pasha in the

Sultan's anny (textpp. rt3-zz).when MahmldPashawas sentby the

Sultan against Sokol and Kluc, Tursun Beg accompanied him (text p.

119).

Tursun participated in the Morean campaign against the Venetians,

again in the company of MahmDd Pasha, in L463. Following the

enemy's flight, Mahmld sent Tursun as a messenger to inform the

Sultan of the victory. Tursun met up with the Sultan, who was at that

time on his way toward the Morea with the remainder of the a-rmy, at

Izdin (Zituni). He was immediately taken into the Sultan's presence

by IsfakPasha, the secondvizir, and made his report. Everyone in the

422 = Halil Inalctk

army rejoiced at the news. The Sultan and government officials all

gave rich presents to Tursun Beg, bearer of the good news. He

received so many presents in money and in valuable goods that even

as he was writing his history he commented:

Ttrrsun Beg, Historian of Mehmed the conqueror's Time

423

MurD.d Pasha (text p. 53). Tursun Beg does not even so much as

mention Mahm0d Pasha's execution. Saying that sultans act with the

guidance and inspiration of God, Tursun Beg refrains from speaking

critically of the Sultan. Nevertheless, he does not hesitate to voice

general cornments about the Conqueror's excessive temper (text pp.

At that time I had vowed never again to complain of

poverty, but now in my old age I am forced to break my

vow. (text p. I25)

In summer L464Tursun Beg was in the company of MahmDdPasha

when he went on the offensive against the Hungarians in Bosnia. After

the Hungarians had retreated, Tursun and Mihal-oghlu Iskender Beg

were charged with the provisioning of the garrison at Izvornik

(Zvornik). In L466 and 1467 Tursun participated, along with the

Sultan and Grand Vizir, in the first and second Albanian campaigns.

According to ourhistorian the Sultan actedparticularly mercilessly in

these campaigns in order to daunt the Albanians into submission (text

pp. 134-38). In July 1468 Tursun Beg's patron Mahmtd Pasha was

dismissed from office. Tursun gives information about the violent

struggle for the Sultan's favor between Mal-lmfld Pasha and his rivals.

While Mahmtd was on campaign against Serbia in 1458, the influence at court of the defterdarDitrik Sinan had grown as aresult of his

being in company with the Sultan on his Morean campaign (text pp.

9l-92). The rivalry between MatrmDd Pasha and Ditrik Sinan ended

with Sinan's dismissal and finally with his death. Later on, as

developments in Karaman grew inpolitical significance, a new group

with expertise and experience in Anatolian affairs gained influence as

the Sultan's advisors. As aresult of this change in the focus of policy,

Ishak, Rum Mehmed, and Gedik Ahmed Pashas were now in the

spotlight, and subsequently were promoted to the Grand Vizirate.

Tursun Beg's treatment of these figures in his history is less than

favorable. On the other hand, hepraises (aramdnTNishanditMehmed

Pasha, who was Gedik Ahmed Pasha's rival (text p. L72).It is likely

that Tursun Beg was on good terms with Mehmed Pasha since, like

himself, Mehmed Pasha was also a milnshl of Turkish origin. During

this period, Tursun Beg advanced rapidly through the ranks of the

finance department, and when Mairmld Pasha was appointed Grand

Vizir for the second time inl473 Tursun Beg was again in his service.

He still attempts to vindicate his benefactor in his treatment of the

campaign against Uzun Hasan which resulted in the death of Khlss

24-25) and impulsiveness (text pp.74, 153). Furthermore, Tursun

tries in his history to demonstrate how Mahmud was always in the

right in his decisions, whether as military commanderor as statesman.

Tursun was active in Malrmld's service, aiding him in all his state and

personal business in the role of a close assistant. As a poet and literary

man Tursun was included in Mahmtd Pasha's private meetings in

which current politics, literature and other intellectual subjects were

discussed (text pp. 23-28). During one of these meetings Hayati, a

poetknown forhis wit and sense of humor, composed a taunting ve se

addressed to Tursun Beg. According to the story in Sehi's Hasht

Bihisht,33 Tursun never forgot this insult and was later held responsible for Hayati' s being put to death. After 147 Tursun Beg, as a highranking official in the Dlvan, accompanied the Sultan on the campaigns which he personally led. As aresult of his being present in the

Moldavian campaign (summer 1476), the campaign against the

Hungarians (winter L476), and in the campaign in Albania (summer

147 8), Tursun Beg was in a position to give interesting original details

concerning these campaigns. But it is evident that he was not present

in the campaigns commanded by the pashas in which the Sultan did

not take part. As a result, his information on the events in Karaman

(7468-74), the crimean campaign (1475), rhe siege of Lepanto

(1477), and the campaigns against Rhodes and otranto (1a80) is

limited, and his treatment of these campaigns in the history is brief and

of a general character.

According to what he himself says in his history, it is clear that after

forty years of government service, Tursun Beg went into retirement

and was allotted the retirement pension set aside for members of the

religious institution.3a During the time in which he was occupied with

writing his history, Tursun Beg was living in Bursa, and his name is

mentioned many times in the Bursa Court Records for the years 889/

7484,892/L487, and 896/L491 in connection with various undertakings. In an entry dated 25 Djumada II 889/20 July 1484, the now

venerable old man, author of our history, is referred to as "iftikhar ala"yan Tursun Beg bn. Hamza Beg." From another of the entries in

the Bursa court records we learn that Tursun Beg's wife was Selguk

424 = Halil Inalctk

Khatun, the daughter of Balaban Pasha.3s That Tursun Beg had trvo

daughters named Mahru and Faktr al-Nisa' is leamed from the Bursa

Court Records. From one of the entries (Sidjill A 8/8, p. 7 gb),we learn that

Tursun Beg was appointed mutawalli (administrator) to his uncle Djiibbe

"Ah's walgf propefiy in Bursa. From another entry (Sidjill no. A 8/8,62b),

dated Djumada I, 896/begins 12. m. I49l,we learn that Tursun Beg sold

his house. It is most probable that Trnsun Beg started to write his history

in Bursa in 1488. At this date he was in all likelihood over the age of sixty.

His date of death is unknown.

TURSTIN BEG'S WORK

Tursun gave the title Tarlkh-i Abu' I Fath,History of the Conqueror,

to his work (p. 11). He, like many other Ottoman historians such as

Idris Bid.lisi, Djelalzade Muqlafh, Selanikr and'Ali, was an historian

belonging to the government secretarial (kuttab) class. Most of these

historians also belonged to that category of bureaucrats known as the

katib-i tadbIr,36 who, as members of the highestrankin the secretarial

profession, were in close relations with all the statesmen responsible

for the formulation of policy. They considered it part of their duty as

historians to record their experiences as an aid to others in the good

management of government affairs. The state secretaries were divided into two principal categories: those specializing in general

government colTespondence, insha' , and those specializing in the

Financial Department, maliyye. Tursun B"g, like Sellnikr and 'Ah,

belonged to the second category. Throughout his history, there are

indications showing his knowledge and familiarity with the profession of a finance secretary. Especially noteworthy in this context is his

attitude towards the material value of conquest and expansion. He

looks upon conquest as a process by which state revenues could be

expanded (text pp. 22,25, 68,89-100, 113, lt7, lzl, 138, 166).

Tursun Beg intends his work, a.record of what had happened in the

past, as a guide and aid to administrators and statesmen in the proper

management of state affairs. He follows the general line of the Advice

to Kings literary geme and subscribes to their approach to political

theory. He puts gleat emphasis on the need for the king's justice and

protection of the re"ayamasses as the foundation of political stability.

Whenever in the course of his history a decision or course of action

is taken in the war councils, he indicates his opinion as to which

decisions were wise and correct and which were wrong and harmful.

Ttrrsun Beg, Historian of Mehmed the Conqueror's Time

425

There is one main theme which runs throughout Tursun's history:

the concept that the good order of state and society is inextricably

bound to the being of the one Sultan. At the time of the history's

writing, everyone in ottoman society was under the influence of the

destructive effects of the civil war which had broken out after

Mehmed II's death. The fear that Sultan Djem, at that time in refuge

in Europe, would return to claim the throne and that civil war would

again blaze out was universal (see especially text pp. 7 -3L, 17 5-84,

198). Sharing this feeling with all those who were concerned with the

well-being of the Ottoman state, Tursun desjred that BayezTd be

firmly established on the throne, and in his history he wanted to

emphasize this point. The long introduction (pp. 1 1-3 1) was cerrainly

written for that pulpose.

At the same time, Tursun did not neglect to express his awareness

that it was through the conquests of Mehmed tr that the Ottoman state

had become the most powerful and respected state in the Islamic

world. Bayezid II wanted an Ottoman history composed that would

show the superiority of the Ottoman House to other rival Islamic

dynasties in Iran and Egypt.37 During just the period in which Tursun

was writing his history, a violent conflict broke out between the

Ottomans and the Mamluks, who backed and supported Djem Sultan

and the Karamanid House in defiance of Bayezid II. It is likely that it

was within the ambience of Ottoman-Mamlukrivalry that Tursun Beg

conceived the idea of writing a history of Mehmed's reign, with which

he was so intimately familiar, and of presenting it to the new Sultan

Blyezid. Tursun gives open expression to his anti-Mamluk feelings

in his history.38

Tursun also makes reference in his introduction (text pp. 9-10) to

the fact that he considered it a debt of gratitude to the late Sultan

Mehmed, for his generosity towards him, to compose a history of his

reign. However, it is made clear that at the same time he expected

some reward from Bayezid II for the writing of his history. In the

appropriate places throughout the text he refers to his poverty and to

Sultan Bayezid's generosity (text pp. 8, 22, I25,I59, I79). Tursun

also states that his purpose in writing the history of Mehmed's reign

was to form the foundations for the history of Mehmed's young

successor (text p. 17 9) . In fact, in the T arlkh-i Abu' I F athitself Tursun

Beg covers the events of Bayezid's reign up to the year 1488. He also

gave expression to his intention to continue his history should his own

longevity permit (text p. 198).

426 = Halil Inalctk

As for Tursun Beg's historiographical methodology and manner of

historical interpretation, he was firmly tied to the basic Islamic belief;

that is to say, according to our author the course of history is

predetermined by God's predestination. Thus, whatever project the

Sultan might undertake, its outcome was subject to this predestination, and success was granted to the Sultan in all his undertakings as

a result of the backing and supporr. (te'ytd) of God (text pp. 15, 160,

170, LgL, Lgg-90, 1gg).

In the Ottoman state and the Islamic states which preceded it, there

had existed an official or semi-official school of historiography which

was based on official government documents, especially corespondence and memos to and frorn the Sultan (talkhl;at).3e Histories

written by historians of this school are detailed and all-inclusive,

usually giving precise and accurate information about the events

described and their dates of occurrence. Another category or school

of historical writing, on the other hand, was exhibited in the personal

histories based on the historian's own reminiscences or experiences

rather than on official documentation. Tursun Beg's history belongs

in this second category. He states in his introduction (text p. 11) that

he wrote his history using information about events which he had

either witnessed himself or information that was currently accepted as

common public knowled ge ( "Beyn al-nas tevatur ile Eabit" ). For this

reason, a great many mistakes are present both in the chronology and

in the protagonists of events which he describes. There are many

important events which we e not personally witnessed by the author

and are therefore left uncovered in his work. It is for certain that his

work is far from being a complete or comprehensive history of the

reign of Mehmed II. The importance of this history derives not from

its completeness, but rather from the fact that it is based on the

personal reminiscences of a man, Tursun B"g, who served for forty

years in the highest government circles, andwho was in close contact

with the influential men and decision makers of his time. TheTarlkhi Abu'l-Fath thus constitutes a first hand source for the study of the

attitudes of the Ottoman ruling class, their inner power struggles, the

character and contents of their war councils, aspects of Ottoman

society and culture whose private nature makes them little susceptible

to study through the official and semi-official histories. Tursun's

work is also one of the most reliable sources for the personalities of

Mehmed II and Mabmld Pasha, as well as for an understanding of the

most important internal and external issues and problems of the day

Tlrsun B.g, Historian of Mehmed the Conqueror's Time

427

as seen by an inside observer.The central importance of artillery for

the Conqueror in his founding of the empire is thus one issue which

is concretely confirmed by Tursun Beg's history. There can be no

doubt whatsoever that it is the most important Ottoman source for the

period of Mehmed fl's reign.

Like most of the milnshts, Tursun Beg was also apoet. The couplets

and verses sprinkled throughouthis history give ample evidence of his

quite considerable skill in the poetic arts. He was given a present of

a sable fur, a robe of honor, and 2,000 akgain cash for the poem which

he presented to Mehmed II on his return to Edirne after the winter

campaign of L47 6 (text pp. 165-66). He also celebrated the occasion

of Bayezid II's first campaign and the conquest of Ak-Kerman and

Kilia in 1484 by greeting the returning Sultan with a verse (text pp.

189-90).

Tursun Beg's history was written in the official literary prose style

which was in the process of development in Ottoman government

circles at that time,ao and can thus be regarded as one of the first and

most important examples of the fifteenth century Ottoman historical

writing. This high-flown literary insha' language seems to have

developed in the time of Murad II on the basis of imitation of Persian

models,al and thus contains many anomalies which were not well

incoqporated into the structure of the Turkish language nor firmly

established in their usage. It is perhaps for this reason that the Tarthi Abu' I Fath was somewhat lacking in popularity among later generations of Ottoman historians.

This work was, however, one of the principal sources upon which

Kemll Pasha-zade relied when he composed the section of his history

dealing with the reign of Mehmed II. Idris Bidlisi and Sa"d al-Din

apparently remained unaware of the existence of Tursun's work.

NOTES

1. Our historian says (M. Arif, ed.ition, p. 8, see note 2 below) his

name is originally Tur-SIna, a Qur'anic name distorted into Tursun

meaning in Turkish, "let him survive." Tursun, a popular name

extensively used in the period was evidently not liked by our author.

Besides, apoet, flayati (Sehi, Tedhkire, Istanbul L325 H. p. 70) made

fun of him by referring to the original meaning of Tursun, which our

author resented.

^w

t#.

428 = Halil Inalctk

2. MehmeO Arif published this work (as a supplement to Tarlkht "O;man/ Endjtimeni Medjmu"asr, Istanbul, 1330 H.) using three

manuscripts, two at the Topkapr Palace Library, Istanbul, Revan no.

LO97 and Revan no. 1098 and one at the Aya Sofya Library (now at

the Stileymaniye Library) no. 3032. In his edition M. Arif relegated

to the footnotes the best version, the Aya Sofya MS, most probably the

original copy presented to Bd'yendll, bearing the seal of this Sultan.

Two more copies are known of Tarikh-i Abu'l Fath, one at the

Topkapr Palace Library, Hazine no. 1470 (see F. Karatay, Tilrkge

Yazmalar Katalo!,u,vol.1, Istanbul,, L967,p.204); and the other at the

national library of Vienna (see G. Fliigel, Die Arabischen, Persischen

undTiirkischenHandschriften.. . ,II, p.207,MS no. 1984). Rhoads

Murphey and I made a facsimile edition of the Aya Sofya Ms with a

surnmary translation: The History of Mehmed the Conqueror,

Biblioteca Islamica: Minneapolis and Chic&go, 1978.

3. See H. Inalcrk, "Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time," rnSpeculum, vol. )OO(V, 1960, pp. 408-27 . A passage from Tursun Beg was

quoted tn a Medjmu"a Q{oprtilii Library, Istanbul, no. 1596,, p. 363).

4. These records are to be found in the stdjill no. A 414: 6b,135b,

I47b,3O4a; no. A 5/5:341a; no. A 8/8: 62a,79b. According to these

records Tursun was present in Bursa at least between Diumada II 8 89/

June 1484 andDjumddaI Sg6fl\zlarch1491. All these sidjillbooks are

at the Bursa Arkeoloji Mtizsi, Bursa; for facsimiles, see H. Inalcik,

"Tursun Beg, Historian of Mehmed the Conqueror's Time," Wiener

Z eitschrift fitr dte Kundes des Morgenlandes,69 (1977).

5. Sidjill no. A 4/q: L47b: Iftikhar al-a"y6n Tursun Beg b. Hamza.

H. Htisameddin (AmasyaTarihi,Ist. 1923 ,p.206) speaks of a certain

"Tursun Qelebi bn. Bakhshdyish Beg" who became defterdar and

muharrir-i vildyet to prince "Ala' al-Din rn 8351I43L-32.

6. Sidjill A 8/8: 62a.

7. ""Ammum Djiibbe"Ali Beg ki o eqnada Bursa Begi idi" (p. 60).

8. Cf. Sa"d al-Din, Tadi al-Tawd.rikh,Ist. 1279 H., p. 316.

9. See Neshri, Gthannuma,I,ed. F. Taeschner,Letpzig, 1951, pp.

61, 67 .

10. P. Wittek, Das Filrstentum Mentesche, Amsterdam, L967 ,

(reprint), p. 81, put the date of the Ottoman conquest of Antalya in the

fall of I39l or early summer, 1392. According to a newly discovered

source (Tariht Tal<vimler, ed. Osman Turan, Ankara, t954, p. 18)

Antalya was first conquered by Murld I in 1388. Now Barbara

iffi

l*

l"

I'

l,

T\rrsun Beg, Historian of Mehmed the Conqueror's Time

429

Flemming, Landschaftsgeschichte von Pamphylien, Pisidien und

Lykien im Spiitmittelalter, Wiesbaden, 1964, pp. 101-09, suggests

that the Ottoman conquest took place between 1397 -99.It may be that

the Ottomans lost the city during the confusion after the death of

Murad at the battle of Kosovo-Polje in 1389. Accordin gtoTakvtmler

(O. Turan, ibid.) Bayezld I invaded "the entfe territory of Teke" in

1390. Our FrruzBeg is often confused with another Fu[z Beg who

was at the frontier on the Danube (B. Flemmin g,II9,l2L,I30; i. H.

Uzungargth, Osmanh Tarihi,I, third edition, Ankara, L972, p. 265).

In Wittek (ibid., pp. 79, 84-85, 1I9, 747, especially p. 86 note 1), our

Frruz is apparently mixed up with the Frruz of Vidin and Khodja Fruz

(Piruz), governor of Menteshe. The latter must be a eunuch, an agha,

perhaps akapt-aghast, when he was appointed governor of Menteshe

(cf. Dr,isrurname-i EnverI, ed. M. Halil, Istanbul, 1928, p. 88: Firuz

Agha).

11. See Sharaf al-Din "AITYazdl, Zafarndma, ed. A. IJrunbayev,

Tashkent, 1972, p. 408a-b.

12. BaEvekdlet ArEivi, Istanbul, Mdliyeden Mildevver Defterler,

no. 9, p. 1 : " Karye-i U ghur gayln khassa-i sandj ak, tlmar-i SilIeyman

Beg,Khudavendigar zamamnda Flruz Beg sattn almtsh, fercrAftan

sonra oghluYa"kub Beg 'ushrin haftzlara walgfetrntsh." In another

place (p. 229): "Ya"kub Beg Destdrlu'yu satun ahdjak Hadjdjt Sinan

elinde duta-durdughu bir giftlik yeri walgf-i ewlad etmtsh, Emlr

Stileyman dahi mr,isellem dutup mektub vermish. . ." See also Neshrr,

ibid., pp. t23-25.

13. Neshri, ibid.

14. Neshn,ibid., pp. 135-36.

1.5. "Murad I[" (H. Inalc:ix) isldmAnsiklopedist,v. 8,pp. 598-601.

16. H. Inalcrk, FAfih Devri tizertnde Tetkikler ve Vestkalar, Ankara, 1954, pp. 37 -53.

17. P. 60.

18. This Hamza has been mixed up with other Hamzas who lived

in the same period. Dukas (ed. V. Grecu, Bucharest, 1958, Index:

Chamza) was mistaken in identifying him with Hamza, brother of

Grand Vizir Bayezid Pasha. The same mistake appears in H.

Hiisameddin (vol. III, p. 203).In his work, HamzaBegTarihi, Bursa,

1949 , AliZiyaTopaE mixed our l,Iamza with Bayezid Pasha's brother

who was active in the 1400's, andHamzaBegwho was killed by Vlad

Dracul in 1461.

14,

43O

= HaIiI Inalc*

9.

Here is a translation of the passage in the Anonymous Chronicles

(ed. F. Giese, p. 60): "At this time Antalya was guarded by Firuz B"g,

one of the well known servants of Mehmed I's grandfather. Mehmed

I had appointed him governor of this place. He died at the time when

Mehmed I died (May, L42l).HarnzaB"g, son of Firuz Beg, the subaEt

(governor) of Karahisar, left there one of his men and came down to

1

Antalya."

20. See "MuradII" |nlsldmAnsiklopedisi, v. 8, pp. 60L-A2.Forthe

dates: F. Thiriet, Registre des ddlibdrations du Snat de Venise

concernont la Romanie, v. II, Paris and the Hague, 1959, nos. 1949,

1980.

21. Voyage d' outremer, ed. Ch. Schefer, 1892, p. 127 .

22. The complex originally included a mosque, a madrasa, and a

zaviye. Of the madrasa only parts of its walls are left. For the actual

position see K6.zrm Baykal,Bursave Arutlarr, Bursa, 1950, p. 36. The

district around the complex is called Hamza Bey Mahallesi after his

name.

23. HamzaBeg married the sister of "Ogman Qelebi of the Teke

dynasty in 83O/begins 2.X.I. 1426 (Sa"d al-Drn, Tadj al-Tawarlkh,I,

Istanbul, L279 H., p. 231).IIer mausoleum, adjacent to the mosque,

houses two tombs besides her own.In1432 Broquidre (ibid.) found

her in the pilgrimage caravan returning from Damascus. It is most

probable that this lady was Tursun Beg's mother.

24. Neshn, ibid., p. 208.

25.H. Hiisameddin, Amasya Tarihi, Vol. III, Istanbul, 1927, p.

23I; documents at the Topkapr Palace Archives (no. 6366) confirm

this information.

26. D. daLezze, HistoriaTurchesca,ed. I., lJrsu, Bucharest, 19 10,

p. 180; H. Hiisameddin, ibid., p. 235; Solakzlde, TarIkh, Istanbul,

t297, p. 873; "Agt Paga-zade, ed. N. Atsrz, Istanbul, 1947,p.243.

27 . S ee document in T. Gdkbil g rn, E dir ne v e P aS a Liv dsr,Istanbul,

t952,p. 47 4. Mustafa Pasha and his wife $adidje Sultan, daughter of

Blyezid II, had a large estate at Kiikiirtli.i-Karamustafa thermal baths

nerr Bursa. fladidje Sultan's mausoleum near the Kiikiirtlii, recently

repaired, is one of the most imposing monuments in Bursa. It houses

eleven tombs. Mustafb Pasha constructed a complex here with a

mosque, madrasa, and a bath (see A. Z.Topag, ibid.). Today only the

b ath, Karamu s tafa Kap hdj a sr, formerly Akg a Hamam, s tands . Mu g lafd:

Pasha's mausoleum is in the court of Hamza Beg mosque.

ti

T[rsun Beg, Historian of Mehmed the Conqueror's Time

= 431

28. If his motherwas the daughterof 'Oqman Chelebr, see note23.

Tursun was a junior secretary rn L444.

29. See my article, "Reis al-Kiittdb," Isldm Ansiklopedisi.

30. H. Inalcrk, "The Policy of Mehmed tI . . . ," Dumbarton Oaks

Papers vol.23-24 (1969-70), pp. 231-49.

3I. "Tursun B eg ve Ishak Q elebt ve Sasa B eg oghlu Qalab-v erdi ve

Kula Subasfust llyas Beg yazdtklart yayamn ve musellemin defteri"

(Bursa, Sidjill no. A 4/4, I35b, 884 H.).

32. See H. Inalcrk, Defter-i Sancak-i Arvanid, Ankara, L954,

Introduction, pp. xiii-xiv.

33. Printed edition, Istanbul, 1325H., p. 70.

34. See Arif's text (pp. 8, 10), "wa?-tfe ve idrdr."

35. Balaban Beg (Pasha) was appointed governor of Menteshe in

829IJ./begins 13. XI. 1425 ('Ashrk Pashazdde,p. 167; Neshn, L57;

Wittek, ibtd., p. 100) when Hamza Beg was governor of Anatolia.

Balaban Beg was at the siege of Salonica in L425 (Iorga, GOR,I, p.

402), was governorof Gallipoli (his mrilkndme dated 1 Muh. 840/16.

August 1436, Topkapr Palace Archives, Sinan Pasha documents no.

156; his waffiyye dated 846/begins 12. V.7442, on the madrasa and

bath he built in Gallipoli, T. Gokbilgin, p. 261), became governor of

Tokat in 1439 (Neshn, p. 168; H. Hiisameddin, ibid.,216), died in

Edirne 850/begins 29.IIl. 1446, and was buried in the court of the

mosque he built in Edirne (for his awl.caf see T. Gokbilgrn, ibid., pp.

63,223-24).

36. See "Reis til-KiittAb," Isldm Ansiklopedisi, vol. 9, p.677.

37 . Historians of the Middle East, eds. B. Lewis and P. Holt,

London, 1962,p. 164.

38. Arif's texr, pp. 183, 192-97: "ki kulun olsa dja'iz Misra

Sultan," (text p. 189). For reference to the fact that Mehmed's last

campaign was intended to crush the Mamluks see pp. I7I-72.

39. Examples of this school of historical writing are Ibn Taghribirdi

among the Mamluks, and among the Ottomans Frndrkhh Si11hd6:r

Mehmed Agha.

40. "Htlye-i insha' ile mutezeyyinbir suret taswir ve takrlr edem"

(p. 1o).

41. Examples of this open imitation of Persian models can easily be

found in Menahidj al-Insha', ed. $inasi Tekin, Cambridge, Mass.,

1973.

Indiana University Turkish Studies and

Halil Inalcrk

Tirrkish Ministry of Culture Joint Series

General Editor:

llhrn

Baggoz

The

Middle East

and the

Balkans

under the

Ottoman Empire

Essays on Economy and Society

Indiana University Turkish Studies and

Turkish Ministry of Culture Joint Series

Vofume 9

o

Br-ooMrNGToN

Hjl?ent Universlty

Halil inalcrk Center

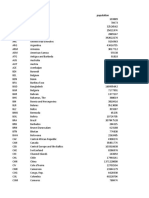

Вам также может понравиться

- Great Is Thy Faithfulness 2019Документ1 страницаGreat Is Thy Faithfulness 2019Adetoyese Adeyeye67% (6)

- Streets and Public Spaces in ConstantinopleДокумент16 страницStreets and Public Spaces in ConstantinopleMyrto VeikouОценок пока нет

- Ottoman Connections To PDFДокумент56 страницOttoman Connections To PDFfauzanrasip100% (1)

- Social Structure and Relations in Fourteenth Century ByzantiumДокумент488 страницSocial Structure and Relations in Fourteenth Century ByzantiumDavo Lo Schiavo100% (1)

- Jewish Anti-Zionism Unravelled, Part OneДокумент8 страницJewish Anti-Zionism Unravelled, Part OneZ WordОценок пока нет

- IslamizationДокумент44 страницыIslamizationtoska35Оценок пока нет

- Anna Komnene's Negative Portrayal of John Italos in The AlexiadДокумент16 страницAnna Komnene's Negative Portrayal of John Italos in The AlexiadConstantinosОценок пока нет

- Luke and DiscipleshipДокумент16 страницLuke and DiscipleshipGerard Jampies100% (2)

- A History of Attila and the HunsДокумент252 страницыA History of Attila and the HunsKarolina Szoverfi100% (2)

- Early Age of Commerce in Southeast Asia, 900-1300 CE, by Geoff WadeДокумент45 страницEarly Age of Commerce in Southeast Asia, 900-1300 CE, by Geoff WadeDmitri Situmeang100% (1)

- Ottoman rule shaped Macedonia's administrative divisionsДокумент19 страницOttoman rule shaped Macedonia's administrative divisionshadrian_imperatorОценок пока нет

- The Geography of The Provincial Administration of The Byzantine Empire (Ca. 600-1200) (Efi Ragia)Документ32 страницыThe Geography of The Provincial Administration of The Byzantine Empire (Ca. 600-1200) (Efi Ragia)Agis Tournas100% (1)

- Andriopoulou - Diplomatic Communication Between Byzantium and The West Under The Late Palaiologoi - 1354-1453 - PHD ThesisДокумент433 страницыAndriopoulou - Diplomatic Communication Between Byzantium and The West Under The Late Palaiologoi - 1354-1453 - PHD ThesisMehmet Tezcan100% (2)

- Imperial Marriages and Their Critics in The Eleventh Century - The Case of SkylitzesДокумент13 страницImperial Marriages and Their Critics in The Eleventh Century - The Case of Skylitzeshanem.tawfeeqОценок пока нет

- Byzantine Plan to Save ConstantinopleДокумент14 страницByzantine Plan to Save ConstantinopleБелый ОрёлОценок пока нет

- The Provincial Aristocracy in Byzantine PDFДокумент295 страницThe Provincial Aristocracy in Byzantine PDFSОценок пока нет

- Byzantine ArmyДокумент7 страницByzantine ArmyDimitris MavridisОценок пока нет

- Bozza, E.agrestide Pno Ed - LeducДокумент13 страницBozza, E.agrestide Pno Ed - LeducLucia Margarita EspinelОценок пока нет

- Despots, Emperors and Balkan Identity in ExileДокумент20 страницDespots, Emperors and Balkan Identity in ExileСара ЂоровићОценок пока нет

- Talbot, Alice-Mary, The Restoration of Constantinople, PDFДокумент20 страницTalbot, Alice-Mary, The Restoration of Constantinople, PDFGonza CordeiroОценок пока нет

- Constantinople and The: LatinsДокумент399 страницConstantinople and The: LatinsGabriel AlexandruОценок пока нет

- Hill - Imperial Women in Byzantium (1025-1204) - Longman - 1999Документ252 страницыHill - Imperial Women in Byzantium (1025-1204) - Longman - 1999IZ PrincipaОценок пока нет

- Janissaries and The Ottoman EmpireДокумент2 страницыJanissaries and The Ottoman Empireapi-503473121100% (1)

- Constantine VII's Peri Ton Stratioton: Danuta M. GóreckiДокумент20 страницConstantine VII's Peri Ton Stratioton: Danuta M. GóreckiHeavensThunderHammerОценок пока нет

- The Perception of Crusaders in Late Byzantine Ecclesiastical ArtДокумент25 страницThe Perception of Crusaders in Late Byzantine Ecclesiastical ArtKosta GiakoumisОценок пока нет

- Vasiliev Justin IДокумент453 страницыVasiliev Justin IthraustilaОценок пока нет

- 0003191Документ5 страниц0003191fauzanrasip100% (1)

- World of The Turks Described by An Eye-Witness - Georgius de Hungaria's Dialectical DisДокумент25 страницWorld of The Turks Described by An Eye-Witness - Georgius de Hungaria's Dialectical DisKatarina LibertasОценок пока нет

- Ruled Indeed Basil Apokapes The ParadunaДокумент10 страницRuled Indeed Basil Apokapes The ParadunaMelkor DracoОценок пока нет

- Byzantium - NobilityДокумент56 страницByzantium - Nobilityoleevaer100% (2)

- Fatih Mehmed Döneminde - Online PDFДокумент461 страницаFatih Mehmed Döneminde - Online PDFfig8fmОценок пока нет

- KAISERKRITIK IN BYZANTIUMДокумент24 страницыKAISERKRITIK IN BYZANTIUMAndrei DumitrescuОценок пока нет

- A Lesson From HannahДокумент2 страницыA Lesson From HannahHC TanОценок пока нет

- The Siege of Constantinople - Seven Contemporary Accounts PDFДокумент213 страницThe Siege of Constantinople - Seven Contemporary Accounts PDFFilip100% (4)

- Pseudo Shapuh BagratuniДокумент63 страницыPseudo Shapuh BagratuniDimitris Spyropoulos100% (1)

- Cumans in Southern Dobrudja - Thomas BrüggemannДокумент15 страницCumans in Southern Dobrudja - Thomas BrüggemannKarela Geiger100% (1)

- Vryonis, The Byzantine Legacy and Ottoman FormsДокумент59 страницVryonis, The Byzantine Legacy and Ottoman FormsVassilis Tsitsopoulos100% (1)

- MST2 2005Документ199 страницMST2 2005Ivo VoltОценок пока нет

- Chaconne: in G Minor For Violin and String OrchestraДокумент8 страницChaconne: in G Minor For Violin and String OrchestraСтас Паращук67% (3)

- Secretaries of The Metropolitan CollegeДокумент2 страницыSecretaries of The Metropolitan Collegealistair9100% (1)

- Byzantine Fortifications: Protecting the Roman Empire in the EastОт EverandByzantine Fortifications: Protecting the Roman Empire in the EastОценок пока нет

- Saint Theodora Empress of ArtaДокумент12 страницSaint Theodora Empress of Artasnežana_pekićОценок пока нет

- John France, Byzantium Confronts Its Neighbours - Islam and The Crusaders in The Twelfth Century, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 38-1 (2014) 33-48.Документ16 страницJohn France, Byzantium Confronts Its Neighbours - Islam and The Crusaders in The Twelfth Century, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 38-1 (2014) 33-48.brc7771Оценок пока нет

- Chronographia - Michael PsellusДокумент205 страницChronographia - Michael Psellusnikica2000Оценок пока нет

- Manuel II Palaeologus and His Circle of ScholarsДокумент17 страницManuel II Palaeologus and His Circle of ScholarsSalah ZyadaОценок пока нет

- OstrovicaДокумент5 страницOstrovicaHaRis HadzihajdarevicОценок пока нет

- Halil Inalcik - Greeks in Ottoman EconomyДокумент8 страницHalil Inalcik - Greeks in Ottoman EconomyAnonymous Psi9Ga0% (1)

- The Battle of Manzikert PDFДокумент26 страницThe Battle of Manzikert PDFjarubirubiОценок пока нет

- The Book of Michael of RhodesДокумент35 страницThe Book of Michael of RhodesHabHabОценок пока нет

- A Collection of Medieval Seals From The PDFДокумент56 страницA Collection of Medieval Seals From The PDFSОценок пока нет

- Despotate of The MoreaДокумент3 страницыDespotate of The MoreaValentin MateiОценок пока нет

- 20 ChaДокумент37 страниц20 ChaKorakovouni WebRadioОценок пока нет

- Tamim Ibn Bahr's Journey To The UyghursДокумент31 страницаTamim Ibn Bahr's Journey To The UyghursJason Phlip NapitupuluОценок пока нет

- The Role of The Megas Domestikos in TheДокумент19 страницThe Role of The Megas Domestikos in TheborjaОценок пока нет

- Movement of People Between Byzantium and The Islamic Near EastДокумент14 страницMovement of People Between Byzantium and The Islamic Near Eastpepepartaola100% (1)

- L.Gmyrya - Hun Country at The Caspian Gate 1995.Документ141 страницаL.Gmyrya - Hun Country at The Caspian Gate 1995.EdekoHun100% (1)

- Erika Nuti Chrzsoloras Pewri Tou Basileos LogouДокумент31 страницаErika Nuti Chrzsoloras Pewri Tou Basileos Logouvizavi21Оценок пока нет

- The Bulgarian Contribution To The Reception of Byzantine Culture in Kievan RusДокумент49 страницThe Bulgarian Contribution To The Reception of Byzantine Culture in Kievan RusUglješa Vojvodić100% (1)

- Who Are The Ancient Bulgarians or Protobulgarians?: Author: Zhivko Voynikov (Bulgaria)Документ200 страницWho Are The Ancient Bulgarians or Protobulgarians?: Author: Zhivko Voynikov (Bulgaria)soulevans100% (1)

- Hunyadi PDFДокумент18 страницHunyadi PDFoverkill81Оценок пока нет

- Byzantium Between East and West: Competing Hellenisms in The Alexiad of Anna Komnene and Her ContemporariesДокумент28 страницByzantium Between East and West: Competing Hellenisms in The Alexiad of Anna Komnene and Her ContemporariesGlen CooperОценок пока нет

- Ben Tov Turco GraeciaДокумент17 страницBen Tov Turco GraeciaElena IuliaОценок пока нет

- Neville 1 PDFДокумент17 страницNeville 1 PDFHomo ByzantinusОценок пока нет

- Mihaloğlu Family PDFДокумент31 страницаMihaloğlu Family PDFAlaattin OguzОценок пока нет

- Averil Cameron - The Construction of Court Ritual The Byzantine Book of Ceremonies PDFДокумент16 страницAveril Cameron - The Construction of Court Ritual The Byzantine Book of Ceremonies PDFMabrouka Kamel youssefОценок пока нет

- Dimiter G Angelov - Theodore II Laskaris, Elena Asenina and Bulgaria PDFДокумент25 страницDimiter G Angelov - Theodore II Laskaris, Elena Asenina and Bulgaria PDFBozo SeljakotОценок пока нет

- Philippides - 2016 - Venice, Genoa, and John VIIIДокумент21 страницаPhilippides - 2016 - Venice, Genoa, and John VIIIKonstantinMorozovОценок пока нет

- SpandounesДокумент96 страницSpandounesDror Klein100% (1)

- Review of Hassan Salih Khalilieh IslamiДокумент6 страницReview of Hassan Salih Khalilieh IslamifauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- The Ottomans and Southeast Asia Prior To PDFДокумент8 страницThe Ottomans and Southeast Asia Prior To PDFfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- The Ottomans and Southeast Asia Prior To PDFДокумент8 страницThe Ottomans and Southeast Asia Prior To PDFfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- A Silence of The Guilds Some CharacteriДокумент16 страницA Silence of The Guilds Some CharacterifauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- Full Paper For The OCEANIA by KayadibiДокумент18 страницFull Paper For The OCEANIA by KayadibifauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- D Mancke Sea SpaceДокумент13 страницD Mancke Sea SpacefauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- With a.C.S. Peacock and Annabel Teh GalДокумент25 страницWith a.C.S. Peacock and Annabel Teh GalfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- With A.C.S. Peacock and Annabel Teh Gal PDFДокумент25 страницWith A.C.S. Peacock and Annabel Teh Gal PDFfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- 201303Документ14 страниц201303fauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- Full Paper For The OCEANIA by KayadibiДокумент18 страницFull Paper For The OCEANIA by KayadibifauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- Index PDFДокумент489 страницIndex PDFfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- Index PDFДокумент489 страницIndex PDFfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- The Influence of 19th Century Dutch Colonial Orientalism in Spreading Kubah (Islamic Dome) and Middle-Eastern Architectural Styles For Mosques in SumatraДокумент13 страницThe Influence of 19th Century Dutch Colonial Orientalism in Spreading Kubah (Islamic Dome) and Middle-Eastern Architectural Styles For Mosques in SumatrafauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- B Turner - Islam Capitalism and The Weber Theses PDFДокумент15 страницB Turner - Islam Capitalism and The Weber Theses PDFfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- Pune Clarence SmithДокумент39 страницPune Clarence SmithfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- A Global History of Ottoman Cotton Textiles 1600-1850 - MWP-2007-30Документ29 страницA Global History of Ottoman Cotton Textiles 1600-1850 - MWP-2007-30Anonymous Psi9GaОценок пока нет

- JSS 088 0q Marcinkowski PersianReligiousCulturalInfluences PDFДокумент9 страницJSS 088 0q Marcinkowski PersianReligiousCulturalInfluences PDFfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- 201303Документ14 страниц201303fauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- Feener Et Al 2011 - Mapping The Acehnese PastДокумент317 страницFeener Et Al 2011 - Mapping The Acehnese Pastfauzanrasip100% (1)

- 10 1 1 610 7156Документ364 страницы10 1 1 610 7156fauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- 25183239Документ30 страниц25183239fauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- Bruinessen Caliphate QuestionДокумент16 страницBruinessen Caliphate QuestionmuhishakОценок пока нет

- Mercan OzdenДокумент71 страницаMercan OzdenfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- 201303Документ14 страниц201303fauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- Brill, Maisonneuve & Larose Studia Islamica: This Content Downloaded From 152.118.24.10 On Sat, 01 Oct 2016 15:04:17 UTCДокумент25 страницBrill, Maisonneuve & Larose Studia Islamica: This Content Downloaded From 152.118.24.10 On Sat, 01 Oct 2016 15:04:17 UTCfauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- 608909Документ35 страниц608909fauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- 4054926Документ20 страниц4054926fauzanrasipОценок пока нет

- DPWALIДокумент26 страницDPWALIMAE ANN TOLENTINOОценок пока нет

- Efficacious Forgiveness - Interpreting the Parable of Unmerciful Servant Matt. 18:21-35Документ8 страницEfficacious Forgiveness - Interpreting the Parable of Unmerciful Servant Matt. 18:21-35mateiflorin07Оценок пока нет

- Questions Skeptics Ask About Messianic Prophecy PDFДокумент33 страницыQuestions Skeptics Ask About Messianic Prophecy PDFComan DanielОценок пока нет

- Khalsa Nitnem PothiДокумент341 страницаKhalsa Nitnem PothiUday SinghОценок пока нет

- FunkДокумент3 страницыFunkrobix73Оценок пока нет

- Doctor List CRMДокумент2 страницыDoctor List CRMrudresh gcОценок пока нет

- How acts of charity and remembrance benefit the deceasedДокумент4 страницыHow acts of charity and remembrance benefit the deceasedmd211Оценок пока нет

- Lady Chatterleys Lover (1981)Документ2 страницыLady Chatterleys Lover (1981)cflamОценок пока нет

- Relative Clauses: Who / Whose: Grammar QuizДокумент1 страницаRelative Clauses: Who / Whose: Grammar QuizLeila JavadovaОценок пока нет

- DelhiДокумент73 страницыDelhiNeha VermaОценок пока нет

- Office of The Director Admissions PG Entrance 2021Документ10 страницOffice of The Director Admissions PG Entrance 2021Syed Shaukat RasheedОценок пока нет

- Country Code Country Name PopulationДокумент6 страницCountry Code Country Name PopulationSara QrmОценок пока нет

- The Story of Ruth The Book of RuthДокумент4 страницыThe Story of Ruth The Book of RuthTrisha CorpuzОценок пока нет

- Act 4 of Hamlet features key scenesДокумент5 страницAct 4 of Hamlet features key scenesRoMe LynОценок пока нет

- Wayside AssignmentДокумент2 страницыWayside AssignmentsashamariethorntonОценок пока нет

- 5 The Jug and Lituus On Roman Republican Coin Types - Ritual Symbols and Political PowerДокумент24 страницы5 The Jug and Lituus On Roman Republican Coin Types - Ritual Symbols and Political PowerElisabetta NebbiaОценок пока нет

- JapaneseДокумент1 страницаJapaneseAbigailОценок пока нет

- AB Turn Into The Passive VoiceДокумент3 страницыAB Turn Into The Passive VoiceFlavius DragomirОценок пока нет

- SSD-15 SA1 CCCM INGO 161-161-Proposal PDFДокумент9 страницSSD-15 SA1 CCCM INGO 161-161-Proposal PDFNana Michael Jehoshaphat DennisОценок пока нет

- Saint Columban's College: Long Test in English 9Документ3 страницыSaint Columban's College: Long Test in English 9roseОценок пока нет

- Chap 6-8Документ111 страницChap 6-8Danniel ZiganayОценок пока нет

- British blues guitarist Aynsley Lister biographyДокумент3 страницыBritish blues guitarist Aynsley Lister biographygojuilОценок пока нет

- RBT T3 BAHAGIAN A B DAN C (1) SortДокумент12 страницRBT T3 BAHAGIAN A B DAN C (1) SortILMAN WAFIY BIN MOHD ZAMRI -Оценок пока нет