Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Journal of Urban History 2003 Jazbinsek 102 25

Загружено:

Robin BenzАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal of Urban History 2003 Jazbinsek 102 25

Загружено:

Robin BenzАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

10.

1177/0096144203258342

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

ARTICLE

THE METROPOLIS AND THE

MENTAL LIFE OF GEORG SIMMEL

On the History of an Antipathy

DIETMAR JAZBINSEK

Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin

German sociologist and cultural philosopher Georg Simmels contribution to Europes urban history has

had an enduring influence, due in no part to the validity of his empirical approach. In his texts, however,

Simmel manages to capture quite accurately the feeling of life in modern urban centersso his readers attestdue to his own experiences as a city dweller. This article asks what kind of experiences he had in the big

city, or could have had, particularly in Berlin.

Keywords: urban sociology; cultural pessimism; Berlin; Grostadt-Dokumente

In the landscape of publications on the history of European cities in the

twentieth century, the contribution by the German sociologist and cultural philosopher Georg Simmel towers above the urban silhouette. Scarcely any discourse on the nature of urbanism and the social impacts of urbanization goes

without one of the classical citations of Simmels observations about the

intensification of nervous stimulation in the city or the specifically metropolitan extravagances of mannerism. This enduring influence is certainly not

due to the validity of his empirical approach. Except for the first scholarly

work that Simmel publishedhis 1879 survey on yodelinghe never dealt

with social research. His texts about cities, however, are equally incomparable

with the historical studies as published in that age by other prominent figures

in German sociology, above all Werner Sombart and Max Weber (in whose

works the modern city is not treated).

If Simmel has managed to capture the feeling of life in modern urban centers as accurately as his readers repeatedly attest, it can only be due to his own

experience as a city dweller, which he later brought into his theoretical considerations. The question in this article is, therefore, what kind of experiences he

had in the big city, or could have had, particularly in Berlin. This approach is

not unusually original. Even while Simmel lived, one of his students, Theodor

AUTHORS NOTE: I thank David Antal for this translation of my German manuscript into English.

Marcus Funck, Bernward Joerges, Jrg Potthast, Heinz Reif, Gert Schmidt, Erhard Stlting, and Ralf Thies

have my gratitude for their support on earlier versions of this article. I owe special thanks to Ani Difranco.

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY, Vol. 30 No. 1, November 2003 102-125

DOI: 10.1177/0096144203258342

2003 Sage Publications

102

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

103

Lessing, made an initial attempt to relate the way of life in his own hometown

to the thinking of his philosophical teacher. Lessings essay began with the day

Simmel was born, March 1, 1858:

No holy star promising peace shown over his birthplace (on the corner of

Leipzigerstrasse and Friedrichstrasse) as it had over Bethlehems manger. No!

Garish illuminated signboards boasted about a smutty world of metropolitan sex

orgies. Trams clanked! Omnibuses chugged by. And the commercial vehicles

piled up in the four criss-crossing densely inhabited streets, whose slick sidewalks reflected the poisonous green gas light from hundreds of street lamps

every evening. And instead of the hallelujah of blessed angels from on high was

heard the insane din from an appalling crowd of people. Loiterers

[Pflastertreter], con men, demimondes, all the scum of Europe streamed along

precisely this building, like hell as defined by St. Theresa: This is the fetid place

without love. Little Georg, however, slept in probably the noisiest cradle that a

philosopher had ever rocked in.1

Clearly, the story was intended to suggest that Simmel was predestined to

become a theoretician of the urban setting because he had been steeped in the

flair of the city from his childhood on. But the lullaby that Lessing intoned

with his expressionist tremolo was flawed, for the street corner on which little

Georgs birthplace stood was still relatively tranquil in 1858. Friedrichstrasse

did not have a bus line until a decade later, at which time it still operated with

horse-drawn vehicles. The road could not reasonably be called a thoroughfare

until March 22, 1873, when the first shopping arcade opened on the corner of

Friedrichstrasse and Behrenstrasse in celebration of the birthday of Emperor

William I.2 The elegant Caf Bauer in 1884 courted customers with the first

illuminated signboards far and wide after the German Edison Company for

Applied Electricity set up a signal box in the cellar of the building next door.

The list of examples illustrating the fundamental change in the streetscape

in the area of Friedrichstrasse and Leipzigerstrasse in the second half of the

nineteenth century could go on,3 but the point is that Lessing plainly was not

describing the urban atmosphere of the year in which Simmel was born.

Instead, he was unabashedly projecting the Berlin of 1912 and 1913, the years

when he wrote the text, more than half a century into the past. This anachronism is salient because it skims over one of Berlins peculiarities in the European context: the boom in the beginning years of the Second German Empire.

Granted, other major European cities, too, experienced heady growth during

that period, but the qualitative basis from which it started was decidedly different. As the centers of the great colonial powers, London and Paris were already

world-class cities when Berlin was still just the residence of the Prussian monarchs. In other words, the place where Simmel was active as a sociologist no

longer had much at all in common with the city of his childhood. Contrary to

Lessing, I therefore assert that Simmel was called to be the theoretician of the

urban setting precisely because he had not become accustomed to the tumult

of the metropolis4 from early life on but rather had been confronted again and

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

104

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

again with what was new and what needed getting used to. He had been confronted with the strangeness of a city in which nothing today is like it had been

yesterday. Simmel himself conceded that this circumstance had crucially

influenced his intellectual development: Berlins development from a city

into a world metropolis in the years around and after the turn of the century

coincides with my own broadest and most intense development.5

To understand what Simmel could have really meant by that statement, I

examine his writings on urban sociology through a biographical lens in this

article. Each of the following four sections recapitulates Simmels relationship

to his hometown from a different perspective: (1) Berlin as a city of workers,

(2) Berlins amusement culture, (3) Berlin as seen from Rome, and (4) wartime

Berlin. But before attempting to understand Simmels texts about cities

through his biography (and vice versa), I return to what he himself wrote about

the impact that cities have on intellectual life.

THE URBANIST MANIFESTO

Having now indicated the special position that Simmels sociology enjoys

in academic literature on the city, I hasten to add that this exceptional status is

not based on his lifes work or even on a multivolume standard collection. It

rests instead on a revised lecture manuscript, the original of which was no longer than twenty-one pages. In 1903, Simmel was invited by the foundation of

the pharmaceutical wholesaler Franz Ludwig Gehe to come to Dresden and

give a lecture, The Metropolis and Mental Life. In 1925, the published version of the lecture was hailed by the Chicago sociologist Louis Wirth as the

most important single article on the city from the sociological standpoint.6

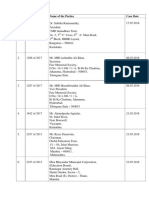

That claim is still viable, nearly a century after its appearance, especially

because the text has become so central to urban sociologists and urban historians alike. In lieu of long paraphrases, I attempt to summarize Simmels reasoning (see Table 1), in which he tried to give urbanism contour as a way of life by

constantly making comparisons with other forms of sociation, which are tentatively subsumable in the generic expression traditional way of life.

Despite the self-contained appearance of Table 1, it does not completely

convey the many layers and ambiguities of the original text. Simmels essay on

big cities defies a straightforward summary for three reasons.

1. Lack of a systematic approach: the inconsistencies in his juxtaposition of the

urban and traditional ways of life arise from a perpetual shift in the yardstick of comparison. Sometimes, Simmel compares the city with the countryside; at other times, he compares the metropolis with the town; and in between,

he continually compares modern urban centers with the cities of earlier epochs.

2. A break with conventional thinking about causality: the imprecision in Simmels

argumentation does not necessarily have to do with intellectual carelessness. As

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

105

TABLE 1

Synopsis of Simmels Lecture Titled The Metropolis and Mental Life

Unit of Comparison

Urban Way of Life

Traditional Way of Life

Main metaphor

Long chains

Small circles

Dominant economic system

Goods production and

money economy

Detailed division of labor

Subsistence production

and barter economy

Little division of labor

Core economic problem

Fight for man

(instill new needs)

Fight with nature

(satisfy elementary needs)

Consumers relation to the

product

Orientation to exchange

value

a

Blas attitude toward things

Consumption of final

products

Orientation to utility value

Sensitivity to differences

Consumers input

Consumers relation to the

manufacturer

Dependence on many people

the consumer does not know

Positive: predictability

Negative: inexorability

General etiquette

Brevity and rarity of meetings

Dependence on a few people

the consumer knows

Positive: latitude for judgment

Negative: arbitrariness

Slight aversion

Length and frequency of

encounters

Solidarity

Benefit to the individual

Individual freedom

Collective support

Danger to the individual

Social isolation

Social control

Leveling of people

Adaptation to formal

procedures (e.g., the

obligation to be punctual)

Adaptation to group norms

Differentiation of people

Stylization of individuality

in public

Knowledge of individualities

a

in the group

Rhythm of life

Tempo

Contrasts

Incessant change

Leisureliness

Evenness

Constancy

Personality patterns

Intellectuality

Tolerance

Flexibility of roles played

Emotionality

a

Philistinism

Stability of character

Life horizon

The near is far; the far is near

a

Cosmopolitanism

The near is near; the far is far

Provincialism

a. Translations of Simmels own expressions. The present translation departs in places from earlier English versions, which are not free from serious errors. For example, the contrast between the

urban and the traditional way of life is described by Simmel as follows: Das Entscheidende ist, da

das Stadtleben den Kampf fr den Nahrungserwerb mit der Natur in einem Kampf um den

Menschen verwandelt hat, da der umkmpfte Gewinn hier nicht von der Natur, sondern vom

Menschen gewhrt wird. The formulation Kampf um den Menschen is translated by H. H. Gerth

and C. W. Mills in Kurt H. Wolff, ed., The Sociology of Georg Simmel (New York, 1964), 420, as

inter-human struggle and by E. Shils in Donald N. Levine, ed., Georg Simmel: On Individuality

and Social Forms (Chicago, 1971), 336, as conflict with human beings.

his colleague Heinrich Rickert stressed, Simmel deliberately avoided system

building.7 This practice is illustrated particularly well by Simmels responses to

the question about the determining factors of social change. In one place, he says

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

106

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

it results from urbanizationthe individuals expanded freedom, for example.

In another place, he explains that social change develops from the money economy. Simmel only superficially suspends this contradiction by declaring that the

urban centers specific nature resides in its being the seat of the money economy. Simmels whole purpose is to take unilinear causalities such as town-airmakes-you-free and dissolve them in a web of interactions. He wants to express

that the city is both cause and effect.

3. A relish for paradoxes: the essays coincidentia oppositorium, its unity in opposites, is a pattern of thinking characteristic of Simmels texts. Urbanization is not

treated as a zero-sum accounting of gains and losses but rather as a process

whose impacts come across as paradoxical at first glance: the simultaneous rise

in the level of the individuals dependence and independence, the simultaneous

increase in anonymity and intimacy in interpersonal relations as one sharpens

the differentiation between them.8

But for all the ambiguity resonating in Simmels theory of urbanism, he is

definite on one matter. The final sentence of the essay contains the reminder

that it is not our task either to accuse or to pardon, but only to understand9 the

city as an entity. The degree to which Simmel himself adhered to this precept is

examined in the following sections.

THE NO-GO AREAS AT THE

TURN OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

As Berlin developed into a center of trade, banking, and finance, old residential neighborhoods in the downtown area had to give way to new commercial buildings. After the creation of the Second German Empire in 1871, labor

migrated to the city, notably from the eastern parts of the country, finding

employment in the new industrial complexes located on the outskirts of the

capital. To cope with the ever more urgent housing problem, it was necessary

to resort to a kind of accommodation introduced earlier by Fredrick the Great,

one that was to become a trademark of modernism in Berlin: tenements

(mietskasernen). In 1908, Albert Sdekum, a deputy of the Social Democratic

Party in Germanys federal diet, published a report summarizing the results of

his research trips to the proletarian quarters in the northern part of the capital. He began by describing the examination of mass accommodations in the

block demarcated by Mllerstrasse and Reinickendorferstrasse. Sdekum

accompanied a physician friend of his on a call to a couple who had to share a

single kitchen room with their three children. It was a hot, humid afternoon in

August, and the stench in the tenement was wretched:

The smell of diapers is typical of all proletarian dwellings. And just as the small

children contribute most to the bad air, they also suffer most from it. What drives

the father to the bar drives the child to the grave.10

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

107

Hell is a fetid place without love.

Sdekums arrangement of the empirical material draws attention to the

influence of his lifelong friend, the sociologist Ferdinand Tnnies. One way

Sdekum demonstrated the representativeness of his reported individual cases

was to cite a school physicians statistics according to which nearly half of all

Berlin school children had to sleep in one room with more than three people.11

These others were not necessarily family members, either. In many cases, they

were people (schlafleute) with whom workers and their families had to share

their dwellings because they could not pay the rent on their own. It takes little

empathy to imagine that most of the attributes that Simmel regarded as characteristic of city lifethe individuals greater independence, the elaboration of

individuality, the surfeit of goods that made life infinitely easy12applied

at most to the quarters of Berlins well to do, not to the involuntary communities in the tenements.

To Sdekum, increased self-responsibility of the individual in modern

times was one of the trite Manchester phrases.13 As a local politician, he

heard it most from deputies of the city assembly who considered the fight

against poverty to be a question of police strategy. Alluding to Nietzsche,

Sdekum referred to his own report on the conditions in the suburbs as

thoughts out of season, by which he wanted to say that public preoccupation

with the miserable conditions of urban housing had already passed some

years earlier. Sarcasm permeated his commentary about the response of the

intellectuals to the situation in the workers quarters and about their influence

on the entire development of the discussion about the social problem:

For a while they put up with the housing issue, too, though preferably the one

in Londons Eastend or New Yorks Bowery rather than that in Berlins

Scheunenviertel or in Recklinghausen; then enoughs enough! Thats just the

way things are. Not only do such people know the least about what is right under

our noses, they dont even want to familiarize themselves with it.14

What is near is far; what is far is near. Taking what Simmel wrote about the life

horizon of urbanites, Sdekum transferred it to the level of social policy, driving home the chill of the social climate prevailing in Berlin in those years.15

The reproach about the ephemeral interest in the iniquities of ones own city

applied to Simmel the sociologist as well. Around 1890, he sympathized for a

time with the Social Democratic Party and, under a pseudonym, submitted

articles to journals that shared the partys views. In later years, he counted this

involvement as one of his youthful transgressions.16 Unlike other Berlin

intellectuals who went over to the next philosophical fashion after a phase of

solidarity with the proletariat, Simmel retrospectively offered an explanation

for their ignorance:

Personal contact between educated people and workers often so vigorously

advocated for the social development of the present, the rapprochement of the

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

108

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

two worlds of which the one does not know how the other lives also advocated

by the educated classes as an ethical ideal, fails simply because of the insuperability of impressions of smell.17

In Simmels opinion, asking the well to do to sacrifice personal comfort, to

go without lobster, lawn-tennis, and chaises longues, is easier than asking

them to engage in physical contact with people to whom the sweat of honest

toilclings. The social question is not only an ethical one, but also a question of

smell [eine Nasenfrage].18

Simmel did not write his commentary Sociology of the Senses from the

perspectiveor better, wind directionof the person smelling of sweat but

rather from that of the person disgusted by the odor. What he wrote about the

affectations of educated people who approach reality with retracted fingertips at most can be read as autobiographical information. This suggestion is

by no means meant as a denunciation. After all, Simmels thoughts about the

connection between fear of contact and loss of reality provide an authentic

answer to the fundamental methodological question of what effects the objects

of observation elicit in the observer and what influence this reaction has on the

cognitive process.19 But when one interprets the manifestation of disgust

cognitively, not morally, a contradiction arises. Although Simmel stressed the

inherent selectivity of perception, which results from perceptions emphasis

upon liking and disliking, he blithely makes his own hypersensitivity the

yardstick of modernity: The modern person is shocked by innumerable

things, and innumerable things appear intolerable to their [sic] senses which

less differentiated, more robust modes of feeling would tolerate without any

such reaction.20 The refinement of taste and an attendant, somewhat aseptic

rejection of what is felt to be unaesthetic were what Simmel saw as modern.

The inhabitants of the tenements were thereby furtively excluded from modern humanity. Life in stench, noise, and filth appeared as something premodern or, as Sdekum aptly put it, out of season.

MODERN AMUSEMENT CULTURE

The misery that existed just a few blocks away, yet seemingly on a different

planet, was something that the young Simmel became familiar with through

the literary dramas and novels of German naturalism. After witnessing an

1892 performance of Gerhart Hauptmanns The Weavers attended by Berlins

intellectual circles, he emphasized the utility of the piece for their social education. This appraisal only heightened his indignation at the decision to censure the play shortly thereafter:

The police permitted performance only for a private association [and] banned

public stagings. Year after year, though, they let the Berlin Residenz Theater

perform the most vulgar French buffoonery, allowing it to exert its educational

effects on our people by titillating sexual feelings and centering all lifes

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

109

interests on the attendant pleasures. In the waxworks there is permission to show

the public a series of bloody acts under the title For Viewers with Strong Nerves,

which thereby systematically brutalizes the young, who are keen on it, begets wanton lust for cruelty, and breeds in humans the instincts of the wild animal.21

To show the absurdity of censoring the workers drama, this passage by

Simmel reproduced the cliches of the cultural criticism in his day. This criticism can be read as an answer to the question of what individuals do with the

expanded freedom granted them by the relaxation of social controls in the anonymity of the city. The conservative elites of the empire, such as the big landowners and the clerics, were convinced that urbanites would use their freedom

for criminal or sexual escapades.22 To the delinquents credit, however, it was

recognized that they did not stray from the path of virtue on their own accord. It

was acknowledged that they had been seduced by a newly arisen amusement

culture running the gamut from the subtle decoration in the department stores

to the parade of feminine enticements on vaudeville stages. The Residenz theater and the Castan brothers wax museum were star attractions of Berlins

early culture industry, which underwent a remake in the golden twenties.

The scandal surrounding the censorship of The Weavers in 1892 was not the

only occasion on which Simmel used the stimulus-response pattern to model

the effect that the new kinds of diversion had on their public. Utter vitriol

against the hollow splendour of modern amusements burst forth in the diatribe titled Infelices possidentes, which Simmel published under the pseudonym Paul Liesegang in 1893. The temples of light entertainment such as the

Apollo Theater in Berlin and the Ronach Theater in Vienna were portrayed by

Simmel as incubators of infection from which the rage for pleasure was

spreading like an epidemic throughout the population:

The terrible and tragic aspect of such domination by the shallow and the common is that it not only takes hold of those of a bad or base disposition, who would

give in to it in any case, but also the better and more noble ones. 23

Simmel saw the causes of this susceptibility in the intensification and monotony of work. Compulsive concentration on occupational life, he asserted, was

compensated for by compulsive diversion during leisure. As Simmel saw it,

this behavioral pattern was particularly true of the well to do, who were able to

afford everything but could scarcely really enjoy anything. The worker, for

whom entry to the pleasure palaces of Friedrichstadt was beyond reach, was

nevertheless supposed to be consoled by the knowledge that the jeunesse dore

of the fin de sicle type only sought to camouflage its inner emptiness by

means of external opulence.

Simmel believed he recognized the contagious nature of this craving for

pleasure (genusucht) also in its capacity to erupt in social contexts having

nothing to do with entertainment at first glance. The Berlin Trade Exhibition

of 1896, for example, was by no means exclusively a commercial fair and a

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

110

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

showcase of German industrys prowess. What arose on the grounds of

Treptow Park on the banks of the Spree River was a Prussian Disneyland with a

nostalgic little set-piece town named Old Berlin; a giant telescope and a panorama of the Alps; a thirty-six-meter-high model of the Great Pyramid of

Cheops, complete with built-in elevator; and an artificial reservoir for staging

sea battles, all of which were won by the German fleet, the pride of Emperor

William II.24 When Simmel contrasted the exhibition style with the monumental style in contemporary architecture and saw the proof of aesthetic

productivity in the way the buildings on the exhibition grounds called attention to their own transience, he momentarily succumbed to the characteristic

logic of this early form of pop culture. 25

However, the tenor of Simmels sociological feuilleton was different.

Arranging every conceivable product into one gigantic ensemble led to a

paralysis of the senses in Simmel when he visited the exhibition. The creators of the exhibition transferred the stimulating dimension of what is

urbanthe richness and variety of fleeting impressionsto a media environment. Simmel the viewer felt like someone who zaps the programs of private television for the first time. And he did not like what he saw. Every fine

and sensitive feeling, however, is violated and seems deranged by the mass

effect of the merchandise offered.26 He also conceded that the effect of

massive quantity can indeed be experienced by less sensitive people as

amusement. He remarked that great care was invested in design and decor

because in the struggle for the consumer, the main thing was increasingly

the shop-window quality of things.27 To Simmel, the economy proved in this

respect to be merely a superstructure of cognitive psychology. Freely translated, Theres no business without show business.

Only people who are already satiated can be coaxed to continue consuming

by means of polished glamour alone. One can therefore assume that Simmel

had the wealthy uppermost in mind when he castigated the slaves of the products, who have lost contact with their inner selves because of endless habits,

endless distractions and endless superficial needs.28 In this critique of decadence, too, Simmel drew on a cliche common around the turn of the century.

One of the most hated social characters to take the stage of German social life

in the era after 1870 was the parvenu. According to a widely quoted statement

by Walther Rathenau, modern Berlin was considered not only the parvenu

among capital cities but also the capital of parvenus.29 Modernizations

winners included corporate founders, engineers, and executives right along

with natural scientists and media intellectuals. There were in fact many newly

rich people in Berlin then, and Simmel, who had inherited a significant sum

after the death of his uncle, Julius Friedlnder, was able to describe quite precisely what it is like to suddenly come into money:

As long as we are not yet in a position to buy things, they affect us with their particular distinctive charms. Yet as soon as we easily acquire them with our money,

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

111

those charms fade away, not only because we now own and enjoy them, but also

because we acquired them by an indifferent method which effaces their specific

value.30

Note, however, that Simmels criticism of this dulling of the capacity to

fully discriminate, this blas attitude, is directed only at those well-off people

whose consumption no longer satisfied any need that could be taken seriously,

such as the development of character. It was aimed at consumption that had

degenerated into an end in itself, into mere consumerism.31 Declaring this distinct form of blas attitude to be the universal trait of urban life clearly shows

how much Simmels image of the city was shaped by Berlins Westend, where

the sociologist spent most of his life. If Berlin was the capital of parvenus at

that time, then the western part of the city was dead center.32 To Simmel, the

nouveau riche of Berlins western quarters were superficiality in person.

Remembering also what Simmel pointed out as the titillation of the senses33

by indecent illuminated signboards and the olfactory impact of masses of people, one begins to suspect that he cannot have felt altogether at ease in his part

of the city. Unsurprisingly, he regarded it as Richard Wagners master stroke

that the composer moved performance of his operas to the Bavarian town of

Bayreuth, for in Simmels opinion the seriousness of serious art could really be

appreciated only in a place remote from modern life.34 Simmel himself, too,

searched for a place of refuge outside the big city.

FROM ETERNAL ICE

INTO THE ETERNAL CITY

Simmel the Berliner had a very special relation to the Alps. Again and

again, he sought out the solitude of the Swiss mountains with his family so that

he could devote himself to writing in peace. Some of his texts are said to suggest their alpine origins because, for instance, they speak of the loftiest

peaks that the author set about climbing in the history of thought. Yet the

mountains were more to Simmel than just a backdrop to and a symbol of his

own thinking. They helped him keenly experience contrast, helped him

achieve a feeling of being delivered from the shallowness of the everyday

world.35 It was primarily the absolutely unhistorical landscape of the glacier regions that enraptured him. In the Philosophy of Money, he conveyed the

intensity of this experience of nature as a symptom of modernism, as a specific

perceptual mode of the urbanite. As Simmel explained, the bond that country

dwellers have to nature was precisely what made it impossible for them to see a

landscape from purely aesthetic perspectives.36

The idyll in the Swiss alpine mountains began to cloud in the 1890s. New

streets and railroad connections brought more and more city dwellers into the

remote areas near Mrren and Adelboden. Simmel protested that alpine tourism became a wholesale opening up. Annoyed, he added,

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

112

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

The concentration and convergence of the massescolourful but therefore as a

whole colourlesssuggesting to us an average sensibility. Like all social averages this depresses those disposed to the higher and finer values without elevating those at the base to the same degree.37

The philosopher fled the city, but the city pursued him. The daredevil climbing

parties of the Alpine Club were a downright scandal to Simmel because the

risking of life as mere enjoyment is unethical.38 In the final analysis, the

addiction to pleasure seeking for which he had criticized the mindless consumer back home was the same malady for which he now rebuked the mountain climbers. With his words, those at the base (den niedrig Veranlagten),

he did not mean the workers, who around 1900 could not yet afford any alpine

trips, but rather the parvenus on vacation.

Simmels criticism of vacation culture suggests a family quarrel, for his

older brother Eugen had published a book titled Walks in the Alps, which

recounted the expeditions of Berlins Alpine Club as adventure stories.39 The

books final chapter contained photographs of the icy graves in which

the corpses of the excessively daring among these pioneers of todays

Erlebnisgesellschaft (society oriented toward the enrichment of personal

experience). In spite of, or rather precisely because of, such misfortunes,

Eugen Simmel tried to deny the appearance of the sensational and to present

mountain climbing as a unique educational experience. With Kants Critique

of Judgment in his backpack, Eugen climbed the Piz Bernina and held forth on

the fortitude of the fearless in the face of natural forces. This educational solicitude found no mercy from his brother. The family expert on Kant categorically stated that the experience of nature was far too brief to contribute to an

abiding enrichment of intellectual life. The uplift which a view of the high

Alps gives is followed very quickly by the return to the mood of the mundane.40 The superficiality of the alpine journeys would be immediately clear if

they were compared with a true educational experiencewith Italian journeys.41

In 1898, Georg Simmel visited Rome for the first time since his youth. The

themes that were to occupy him in his lecture titled The Metropolis and Mental Life five years later do not appear in his travel report. As emphasized by

the reports subtitle, Simmels observations were an aesthetic analysis, not a

sociological one. To Simmel, the aesthetics of the Italian capital consisted in

the way the disparate details of the urban structure fit together into a harmonic

whole. In a footnote, he stated that he owed this holistic impression to a carefully delimited scope: I may disregard the parts of Rome that are of unremitting modernity and equally unremitting atrociousness. Fortunately, they lie

where, with a bit of caution, they will be of relatively little concern to the

stranger.42 Rome was (and is?) the paragon of the ancient city, whereas Berlin

then (as now?) was perceived as a giant construction site.43 One of the most

influential depictions of Berlin as a test-tube city without tradition is found in

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

113

Julius Langbehns book Rembrandt als Erzieher (Rembrandt as an Educator).

Reviewing this bestseller in 1890, Simmel did remonstrate that its author

lacked a higher order perspective. As long as the eye is fixated on this or that

discrete phenomenon of modernism, one would like to think that telephones,

mountain railroads, factory smokestacks, and the citys endless monotonous

streets lined with houses are the most antipoetic things in the world.44 But

eight years later, he adopted Langbehns stance and was no longer able to see

telephones, factory smokestacks, or asphalt streets as manifestations of poetry

rooted in reality.

Simmels text on Rome deals with what he misses at home, what oppresses

him there.45 At the sight of the Roman ruins, the present merges with the past in

the eyes of their beholder from Berlin. The panorama of the eternal city evokes

in him a feeling similar to that brought on by the sight of the eternal ice: being

free from all here and now. But at the very moment Simmel declaresin

pathos typical of the periodhow overcome he is with emotion, his field of

vision is violated by that irksome element, a tourist. Although Simmel is a

tourist, too, he is not the typical pleasure traveler. Already feeling himself

unpleasantly affected elsewhere by human beings of this species, Simmel

finds them more stylistically incongruous and intolerable in Rome than otherwise.46 The typical thing about typical pleasure travelers is that they only

pay attention to individual sights: The subhuman and primitive human consciousness is stuck in the isolation of its notions; the sign of higher [human

consciousness] and the proof of its freedom and supremacy is that it draws

connections between the particulars.47

Nor was Simmel spared the irritation about primitive human consciousness while in Florence, where he often spent his semester breaks. From travel

guides in circulation around the turn of the century,48 one gathers that Michelangelos sculptures in the Medicis family tomb in Florence were among the

musts for the Tuscany faction of Germanys educated middle class. Simmel, an

admirer of Michelangelo, was therefore unable to devote himself to enjoying

art in peace there. In a diary entry after a social evening on October 3, 1903,

historian Kurt Breysig noted, Simmel complains about the public in the

museums; 7 minutes long in the Medici chapelmeaning: nonetheless have

a vague yearning for beauty.49 The most profound reason for the resentment

that Simmel the sociologist felt toward the German capital may be that regardless of where he fled, he always came across his unloved neighbors from

Berlin.

SIMMELS STUDENT JULIUS BAB AND

THE GROSTADT-DOKUMENTE SERIES

After never rising above the rank of associate professor (extraordinarius) at

the Royal FriedrichWilhelm University in Berlin, Simmel accepted a chair at

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

114

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

the University of Strasbourg in April 1914. When the news of his imminent

departure became public, the journal Die Gegenwart printed an editorial,

Berlin without Simmel, lamenting that the city was losing one of its most

spirited forcesa truly extraordinary scholar whom an entire dozen of the full

professors do not make up for. Simmel and his family were highly gratified to

read this article, though it did strengthen the doubts about whether the decision

to leave Berlin for the provinces was the right one.50 The author of the article,

the thirty-four-year-old theater critic Julius Bab, had regularly attended Simmels

lectures as a student and had maintained amicable relations with his teacher in

the years thereafter.51

The publication that had made Bab known overnight was his 1904 portrait,

Berlin bohemia.52 Whereas a year earlier Simmels famous lecture had characterized cities as places in which the most tendentious peculiarities of selfaggrandizement thrived, Bab noted how far the cultivation of eccentric deportment had advanced in Germany. Bab was personal friends with probably the

most conspicuously shabby and unruly [looking]53 of all Berlin bohemians,

the anarchist Erich Mhsam. Bab asserted that the egocentrism of cultural

gypsies such as Mhsam acquires a new dimension in the city because the

loners there can join together as a community:

The bohemian is a child of the city, conceived and born of these centers of modern culture, which endeavor to gather all talents within them. . . . There have

always been individual bohemians, but a bohemia has existed only since the

advent of modern metropolises.54

Only in a city of millions does the number of dissidents reach the level needed

to establish their own meeting places, publications, group rituals, and clothing

styles.

This train of thought may be obvious today, but in the early twentieth

century, it was unusual and confusing. The prevailing image of the city in

Germany around 1900 was one of disorder. Invoking Tnnies, observers associated the process of urbanization primarily with the dissolution of traditional

communities. Simmel, too, posited a loss of community ties in the city but juxtaposed it with gains in individual freedom and came up with mixed results.

Bab, by contrast, associated individualism as a lifestyle with the emergence of

new, modern forms of group formation. His overall judgment of urban culture

was correspondingly positive, especially because he accorded the outsider

communities an important social function. He saw no cause for censure in their

attack on the societys habitual and convenient lies. To him, it was instead

creative destruction, an engine of modernization.

Julius Bab considered his chronicle of the Berlin bohemia only an initial

sketch, a preliminary study for a great, historically critical work55 in which

he also wanted to study criminal and professional communities to determine

what influence the city exerted on the search for identity among marginalized

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

115

groups. Bab thereby anticipated a principle that Claude S. Fischer elaborated

seventy years later in his subcultural theory of urbanism.56 Fischers central

thesis was that deviations from the norm in an agglomeration can reach a critical mass that lends the very quantity of rule violations a new quality, the

quality of an independent subculture. 57

Although Bab himself did not follow up on his research program, at least

parts of it were pursued later in the series in which he had published his book

on the Berlin bohemia. From 1904 through 1908, fifty-one monographs

appeared in this series, which carried the title Grostadt-Dokumente. Its editor, Hans Ostwald, chose the study on the bohemia as the second volume after

he himself had scouted the dark corners of Berlin in the first volume, albeit

without attempting to stake out a theoretical position.58 This decision is interpretable as an indication that Ostwald saw Babs ideas on the sociology of the

social outsider to be a systematic outline for the entire urban research project.

To be sure, the series went on to include studies not only on the subculture of

bohemians but also on gamblers, esoterics, pimps, athletes, professional criminals, anarchists, and homosexuals.59 Among the forty authors who worked on

the project, Ostwald was surrounded by a core group of scholars who had close

contact with each other through their mutual affiliation with artistic circles,

press editorial departments, and associations for social reform. It is this intellectual milieu of the Berlin bohemia that Julius Bab described so vividly,

which is why his contribution to the series can also be read as a self-portrait of

the authors community.

When writing about the city, Simmel confined himself to the segment of

reality he knew from his own everyday world. Ostwald and his coauthors,

however, predicated their work on the systematic inquiry into unfamiliar areas

of the city, using various observational and descriptive methods ranging from

walking tours to biographical interviews and the printing of personal documents.60 Most of the procedures would be classified today as qualitative social

research, but sociological naturalism seems a more appropriate term for communicating both the pathos of authenticity and the predilection for marginal

existence that were reflected in the Grostadt-Dokumente series. Indeed,

Emile Zola and the German naturalists exerted great influence on the Berlin

community of authors.

Given the projects vast range of methods and spectrum of topics, it is

exceedingly difficult to find a similarly encompassing early-twentieth-century

undertaking classifiable as urban researchin the broadest sense. The closest

contending body of work is that of the Chicago school of urban sociology,

which was started approximately a decade later under the direction of Robert

E. Park, though the methodology involved was far more refined and the theories more sophisticated. There were in fact many indications that the Ostwald

series was closely studied by the founding generation of the Chicago school.61

In Louis Wirths famous 1925 bibliography of scientific literature on urban

sociology, for example, Babs article was praised as a unique contribution to

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

116

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

the mentality of city life.62 Beyond this tribute, almost all other individual volumes of the Grostadt-Dokumente series were listed and commentated, with

Wirth expounding on some of their leitmotifs and translating them into the terminology of Chicago urban sociology. In so doing, Wirth tackled a task that

had been neglected by the Berlin authors: the analytical penetration of the

factual material that was spread over more than five thousand pages of text in

Grostadt-Dokumente. What Park had done in Chicago with the prefaces for

the classical studies of his doctoral students was far beyond what had been

manageable in Berlin by Ostwald, who was a goldsmith by trade and a selftaught journalist. Ostwald had instead trusted that his readers would relieve

him of the work of analyzing and synthesizing. A characteristic passage

expressing this approach is Ostwalds introduction to volume 33, in which the

diary of a convict is printed: I deliberately refrain from further commentbut

expect that psychologists, criminologists, sociologists, politicians, philanthropists, and misanthropes will appreciate the value of this document and

extract the pulp from the rind.63

In purely theoretical terms, Georg Simmel could have been the sociologist

for that job, particularly because personal contact to the Berlin community of

authors existed through Julius Bab.64 Realistically speaking, however, the

Ostwald project came at least ten years too late for Simmel. By the time his students bohemia essay appeared, Simmel had long since made the switch from

social involvement to formal sociological analysis, from naturalism and

social democracy to aestheticism and the circle surrounding George, from

sociology to metaphysics.65 There is hardly a greater contrast than that

between Ostwalds fascination with the diversity of city life66 and Simmels

distaste for Berlins titillation of the senses and intoxication of the nerves.

This difference is apparent, among other things, from the style of the social

gatherings that Simmel cultivated with his friends and acquaintances in

Berlins Westend. Part of the genteel etiquette in Simmels salon meant ensuring that conversation avoided mention of the surrounding city. As reported by

Elly Heuss-Knapp, a firsthand witness of the jours in Simmels private apartment in 1906: There is never talk of what is currently occupying Berlin, but

rather of the special rhetoric used by the French in the Dauphin against the

northern French or of other things no one else knows about. I like listening.67

Such words express once again the notion that what is near is far, and what is

far is near. There were other exclusive salons in Berlin that existed at the turn of

the twentieth century, but Simmel considered them more trivial forms of fellowship, as he stressed in an invitation to Stefan George, his most prominent

guest: The Berlin world reposes in dinner parties, social gatherings, and other

things one can buy, and that makes a good periphery for our ever quieter and

more concentrated life.68 To the rest of the world, the big city became nothing

more than a distant background noise helping the intellectual elite to achieve

an even more intense feeling of turning away from the world. It may be the

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

117

appropriate setting for a poet of the transcendental, but is it for an observer of

modern times?

BABYLON BERLIN IN THE GREAT WAR

1 August, war! The greatest shock of my life. . . . The furor teutonicus is

unleashed and rages in me as well.69 This entry in the memoirs that Hans

Simmel wrote in American exile during World War II describes his fathers

reaction to the outbreak of World War I. As long as Georg Simmels strength

permitted, that is, until he fell ill with cancer at the turn of 1917 and 1918, he

tried to contribute nonmaterially to the self-assertion of the German Empire in

a world of enemies. He worked late in the evenings at the censors bureau of the

Strasbourg telegraph office, took a hand in foreign propaganda, and agitated

against the French policy of retaliation and revenge and against Englands

hunger for gold. On speaking tours within Germany, he made a point of

declaring his love for the fatherland, and he gave university lectures at the

western front.

Simmels activism did not differ markedly from that of the other German

sociologists, who did not hesitate long to volunteer for the combat patrols of

ideological warfare.70 But coming from an author with a fondness for such

niceties as coquetry and sake bowls, the crudeness of the belligerent is more

surprising with Simmel than with the other representatives of the field. It is

even more startling than with Sombart, Tnnies, and Weber, who, for all

their proclamations about freedom from value judgment, seldom shunned

the opportunity to interfere in daily politics. With Simmel, the shift from

theorizing about individualism to rooting for the nation comes across as a

radical break with his own past. The patriotic tones in his writing during

the war are new when compared with the tenor of his earlier texts. He never

used to think about what sets Teutonism apart from the Romanesque and

had never before tried to distinguish between genuine German cosmopolitanism and the globetrotters diffuse gushing about foreignness (verblasene

Auslnderei).71 Such phrases suggest that Simmels enthusiasm for the war be

equated with a temporally localizable sacrificium intellectus and that his work

be regarded as essentially unscathed by the causes and consequences of German militarism.

This conclusion amounts to a serious misinterpretation, as demonstrated by

Simmels first wartime speech, which he gave on November 7, 1914, in

Aubette Hall in Strasbourg. Simmel expressed his deep relief that the epoch

since 1870, the era of Berlin modernism, had irrevocably come to an end,

linking the hope for a renaissance of the German people and culture in the form

of a new man. Just as the war of 1870-1871 helped the German nation

achieve its economic potential, the new Great War couldso he asserted

lead to the mobilization of their spiritual reserves by eliminating one of the

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

118

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

root evils of Wilhelmine society, mammonism, which he defined as the

worship of money and of the monetary value of things.72 Mammonism was

thus nothing other than a new, more concise formulation of Simmels old conviction that money had ceased being a mere means of payment and had made

itself the ultimate purpose of human existence. Furthermore, the statement

that this development of the golden calf into something transcendent . . .

became endemic in our major cities ought to sound familiar to the readers of

Simmels 1903 essay on the city. In the lecture The Crisis of Culture, which

was delivered in January 1916, Simmel reiterated the same basic idea more

systematically and more abstractly: lifethe protagonist in Simmels metaphysicsfinally defends itself against its rape by the mechanics of modernism. He stated with unmistakable clarity in the endnote to the printed version

of the lecture that the foundations of the historiocultural and historiophilosophical bases of these considerations are thoroughly described in my

book The Philosophy of Money.73

How far the equating of war and catharsis removed Simmel from the conceptual world of his countrymen is shown by the fact that he based his hopes

not on possible victory but rather on the probability that Germany would be

impoverished. Remarkably, Simmel was persuaded of the latter scenario

within just four months after the war broke out. Germany will be a poor laggard by comparison.74 He deleted an additional clauseeven if a happy end

to the war restores billions to herfrom the 1917 reissue of his first wartime

text, for by then a happy outcome was no longer likely. From the outset, making a virtue out of necessity had been more important to Simmel than victory

or defeat. The privations of the war economy were to teach Germany a more

sensitive, less blasI would even go so far as to say a more reverentrelationship to the commodities which we consume daily.75 The state indicates

that Simmels antipathy, as in his prewar texts, once again railed primarily

against the craving for pleasure of people with a blas attitude. People who

could barely afford the simplest articles of daily consumption already existed

in Germany during peacetime, but now those who used to be guilty of mammonism were expected to sacrifice what they cherished mosttheir money.

In February 1915, Simmel called for this sacrifice by launching a headstrong food campaign that was to occupy him for more than two years. His

Lenten sermon to the wealthy, which was circulated in newspapers and journals, laid down the law on the heresy that misconceived thrift constituted:

Today, the catchword savings is leading former consumers of sole, artichokes, and beef filet to eat haddock, white cabbage, and roast knuckles

instead.76 The examples varied: People who had been used to lobster salad,

young carrots, and partridge were suddenly eating green herring, old carrots,

and hash made of calfs lung.77 The message was the same, however: whoever

could afford the most expensive food should continue eating it during the war

as well so that the inexpensive foods remained available for the other groups in

the population.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

119

Simmel thereby addressed the chief problems of Germanys war economy,

the bottlenecks in the supply of food to the population, especially in the big cities and above all in Berlin. He greatly welcomed the decision to ration staple

food, a measure born of necessity. Beginning on February 22, 1915, flour and

grain in Berlin were allocated by means of bread ration-cards. This distribution system was typical of so-called wartime socialism and was soon expected

to extend to other everyday goods and other regions of the German Empire.

Simmel rejoiced,

The bread ration-card symbolizes the uselessness of even the greatest wealth. . . .

At last people are again being asked to economize with meat and butter, bread

and wool, for the sake of these commodities themselves. This change may sound

simple, but it totally reverses a sense of economic value which has been nurtured

for centuries in the civilized world.78

The sense of economic values characteristic of the barter economy is what was

finally supposed to reassert itself. What Simmel the Lenten preacher had in

mind is tantamount to a revival of the traditional way of life79 on an urban scale

and at a national level.

Simmels vision took no account of the everyday world in the regions

behind the war of position. Each person with a bread ration-card was to receive

about eight ounces of flour a day, which, if stretched with a potato additive,

corresponded to a little more than four pounds of bread.80 Approximately

800,000 people, most of them in the capital, are estimated to have starved to

death in Germany during the years of the Allied economic blockade of the

country. In the midst of the war, Berlins topography began to deurbanize, with

a bizarre form of the barter economy eventually taking over within the city.

Potatoes were cultivated in parks and open areas, balconies were used for

growing tomatoes, and chickens and rabbits were raised in back courtyards.

The universities feverishly conducted experiments with new, synthetic foods,

such as flour made from finely ground tree bark, pudding powder made from

gluten, and pepper made from ash. Supply gaps opened the way for the black

market and the underground economy. Only solvent customers could pay the

exorbitant prices for illegally procured goods. A wartime version of the parvenu arose with the profiteer of black marketeering and the chain trade. Corruption existed everywhere, but only in Berlin did it emerge into a way of life,

highlighting the extreme inequality of access to food in the German capital.81

In far-off Strasbourg, Georg Simmel eventually also began to note the catastrophic conditions in his hometown. A footnote to a collection of articles published in the book titled Der Krieg und die geistigen Entscheidungen (The War

and the Decisions of the Mind), which appeared in mid-1917, he conceded,

The war years that have meanwhile elapsed, with profiteering and overcharging, hoarding, and methods of war-tax evasion, have shown that there can be

no talk of a general endeavor to overcome mammonism.82 But even then he

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

120

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

could not yet bring himself to give up the idea that the war was accomplishing a

metaphysical feat: The war has brought life a tremendous increase of

intensity that which the wonderful people have become even more wonderful and the knaves even more knavish. At the same time, the revision of his

original expectations was associated with their radicalization into a fantasy

of annihilation: The cozy tranquility of peace can perhaps afford to carry

along what is superfluous, what is innerly dead[.] . . . This is no longer compatible with the toughness and decisiveness to which the war has hammered out

our existence.83 And uppermost on Simmels list of what is innerly dead

superfluous people. It is that which is without right to the future: People and

institutions, world views, and concepts of morality.

He thus seemed to have sensed that the war would not meet his desire for

annihilation. When he works himself up over the old mammonistic Adam, it

sounds more like a curse than like philosophy. His Old Testament wrath is not

directed solely at the materialism of the monied classes but also at the big

city, at Berlin, where culture suffered the fate of the Tower of Babel84 and

where the golden calf became transcendent. In Simmels religion of education, modern Berlin is what ancient Rome was according to Augustinian

allegory85the hotbed of vice, the city of vulgarity and idolization of money

with modern Rome taking the place of biblical Jerusalem.

BERLIN, SIMMELSTRASSE, MARCH 2001

In late 1914, Simmel had been able to extemporize, as it were, a meaning

for the war because he had spent years in mental mobilization. It would be

an injustice to him to regard his radicalization of The Philosophy of Money

into a uniquely Simmelian variant of the German steel-bath philosophies

(stahlbadphilosophien) as a misinterpretation of his own work, as a retrospective prophecy belatedly claiming to have seen from the outset how things

would turn out. Simmel had actually foretold much earlier that the pathology

of culture would inexorably lead to the outbreak of the crisis.86

On the walls of the Berlin entertainment establishments there stands the mene

mene tekel; the marble and the paintings, the gold and the satin that cover them

seek in vain to cover the writing, it penetrates through the present, and todays

seers know how to interpret it.

Two decades before Verdun, these words marked the start of Infelices possidentes. A few lines later, Simmel added an oracle: A terrible seriousness will

not only replace this gleaming intoxication.87 The seer from Friedrichstrasse

did not merely divine the terrible seriousness; he longed for it: Give us, o

onrushing times, give to us reverence again. In 1900, he wrote a poem

inspired by the turn of the century, concluding it with this prayer formula to

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

121

express a feeling unmistakably stressed from the very title through to the punctuation: A yearning.88 That same year, Simmel made a statement in The Philosophy of Money that has puzzled many a scholar studying his works: Modern times, particularly the most recent, are permeated by a feeling of tension,

expectation, and unreleased intense desiresas if in anticipation of what is

essential, of the definitive[,] of the specific meaning and central point of life

and things.89 The passage sounds less puzzling if one reads one sentence further, for Simmel mentions there the most striking example, aside from

money, of mere preparation, a latent energy, a contingency. He meant the

regular army and the negation of its end: to wage war.

The fact that Simmel secretly understood himself as a prophet of impending

doom already in peacetime was not lost on his contemporaries. His student

Theodor Lessing, for example, intended this very message when he had little

Georg grow up amid a hallucinated filthy world of metropolitan sex orgies

and stylized him into a new messiah called to take a whip and drive the money

changers from the Holy Temple.90 To Simmel, this moment of reckoning

seemed to have come with the outbreak of the Great War, the dawn of the

great era. What used to displease him about urban culture he now interpreted as degeneration resulting from the culture of peace.91 And quiet aversions then became vociferous aggressions.

Why has the link between Simmels wartime texts and urban texts been so

rarely discerned since that time? Why have so few observers seen the perfumed Nietzscheanism of a man who combined the refinement of his own,

higher mental life with the contempt of all people he classified as lower

human beingsa man who is considered an urbanist (and a modernist) par

excellence, although he bequeathed a work clearly laced with antiurbanist

(and antimodernist) affects? There are a kind explanation and an unkind explanation of the usual interpretation of Simmels urban sociology, in which his

pitch-black cultural pessimism is perceived at best as a gray veil. According to

the unkind version, what Simmel wrote of Julius Langbehns success applies

to his own:

I mean the success achieved everywhere by pure brilliance as such. That the

people to whom we owe what is true and deep in content were often also capable

of brilliant form, astonishing analogies, the ability to capture colorful appearances in a fitting wordthat has generated the utterly wrong opinion that these

formal characteristics already have the value of truth and depth. What contributes to this is the vast number of literary productions and the cursoriness of the

reading caused thereby.92

The kind explanation for the one-sided reception of Simmels work amounts to

saying that his texts have been read as he wished his readers to read them: One

should gratefully absorb from a book what is edifying and simply pass over the

other.93 Should one? Can one not be grateful for everything there is yet to learn

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

122

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

from Simmels books and nevertheless refuse simply to pass over the other,

sociologically dubious aspects in his work?

Along with several works that were brilliant only in form, Simmel the

man left a great deal that was true and deep, and the city of Berlin showed its

thanks by naming a street after him.94 Of course, traffic arteries such as

Friedrichstrasse and Leipzigerstrasse were out of the question for this purpose.

But streets with less tradition, such as Nussbaumallee and Lindenallee in the

noble Westend quarter, were not considered, either, although they would have

been fitting for Simmel because he had felt the area to be his home for a while.

The street that was ultimately chosen lies in the far north of the city, in what

used to be a proletarian residential part of Reinickendorf, a vicinity that

Simmel probably never would have voluntarily set foot in. When I asked a resident of Simmelstrasse about the person after whom the road was named, she

shook her shoulders in perplexity. The only metropolitan sound drowning out

the birds chirping in the trees lining the street is the noise of the passenger airlines taking off and landing at nearby Tegel airport at regular intervals. Naming this urban village street after the world-famous professor may still have

been a way of showing deference, but it is also a kind of vengeance for the considerable antipathy lining Simmels ambivalence toward his hometown. It

would be unusual if the authors extensive work were to contain no quotation

in keeping with this sublime form of revenge: It is the subtlest and often most

ineluctable revenge exacted by powers of fate that they grant us the substance

of our desires and completely reverse it into its caricature merely by granting

more of it or less.95

1. Dies ist der Ort, wo es stinkt und man nicht liebt, Theodor Lessing, Philosphie als Tat, Erster Teil

(Gttingen, 1914), 303.

2. The biggest attraction of this Imperial Gallery became the wax museum by the brothers Louis and

Gustav Castan, whose exhibits included not only famous figures such as Napoleon Bonaparte but infamous

ones such as Jack the Ripper (much to Simmels consternation, as shown later in this article).

3. Ralph Hoppe, Die Friedrichstrae: Pflaster der Extreme (Berlin, 1999).

4. Georg Simmel, The Philosophy of Money (1900), translated by Tom Bottomore and David Frisby

(London, 1990), 484.

5. Hans Simmel, Auszge aus den Lebenserinnerungen, in Hannes Bhringer and Karlfried Grnder,

eds., sthetik und Soziologie um die Jahrhundertwende: Georg Simmel (Frankfurt am Main, 1976), 265.

What is true of Simmel is, of course, also true of the other classical thinkers of early German sociology who

tackled the topic of urbanization. Weber (born in 1864), Sombart (born in 1863), and Ferdinand Tnnies

(born in 1855) all belonged to this generation of sociologists, for whom Berlin modernism became a key

experience, though some of them discussed it only from afar. I am unable to judge whether this relationship

to the urban environment justifies the conclusion that the idea of the modern city is an invention typiquement

allemande. See Stphane Jonas, La mtropolisation de la socit dans loeuvre de Georg Simmel, in Jean

Rmy, ed., Georg Simmel: Ville et modernit (Paris, 1995), 53.

6. Louis Wirth, A Bibliography of the Urban Community, in R. E. Park, E. W. Burgess, and R. D.

McKenzie, eds., The City (Chicago, 1925), 219.

7. Heinrich Rickert, Die Philosophie des Lebens (Tbingen, 1920), 26.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

Jazbinsek / GEORG SIMMEL

123

8. The latter aspect, the appreciation of the value attached to privacy in the city, is one of the few basic

thoughts on urbanism in The Philosophy of Money that Simmel did not mention in his Dresden lecture (see

Ibid., 469). Apart from that difference, The Metropolis and Mental Life can be read as a summary of the

second, synthetic part of his magnum opus. See Otthein Rammstedt, Simmels Philosophie des Geldes,

in Jeff Kintzel and Peter Schneider, eds., Georg Simmels Philosophie des Geldes (Frankfurt am Main,

1995), 34.

9. Georg Simmel, The Metropolis and Mental Life (1903, trans. by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills),

in Kurt H. Wolff, The Sociology of Georg Simmel (New York, 1964), 424.

10. Albert Sdekum, Grostdtisches Wohnungselend, Grostadt-Dokumente, vol. 45 (Berlin, 1908),

34.

11. Ibid., 46.

12. Simmel, Metropolis and Mental Life, 422.

13. Sdekum, Grostdtisches Wohnungselend, 7.

14. Ibid., 6.

15. In subject matter and sometimes in tone, Sdekums ridicule of the lovers of pressed raspberry lemonade evokes Tom Wolfes coverage of the radical chic of New York high society in the late 1960s. See Tom

Wolfe, Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers (New York, 1970).

16. Klaus Christian Khnke, Der junge Simmel in Theoriebeziehungen und sozialen Bewegungen

(Frankfurt am Main, 1996), 23-24.

17. Georg Simmel, Sociology of the Senses (1907, trans. by Mark Ritter and David Frisby), in David

Frisby and Mike Featherstone, eds., Simmel on Culture (London, 1997), 118.

18. Ibid. See also Georg Simmel, Soziologische sthetik (1896), in Georg Simmel, Gesamtausgabe

(GSG) (Frankfurt am Main, 1992), vol. 5, 205.

19. Georges Devereux, From Anxiety to Method in the Behavioral Sciences (Paris, 1967).

20. Georg Simmel, Sociology of the Senses, 117-19.

21. Georg Simmel, Gerhart Hauptmanns Weber (1892), in Werner Jung, ed., Georg Simmel: Vom

Wesen der Moderne (Hamburg, 1990), 166.

22. Ralf Stremmel, Modell und Moloch. Berlin in der Wahrnehmung deutscher Politiker vom Ende des

19. Jahrhunderts bis zum Zweiten Weltkrieg (Bonn, 1992), 100-104.

23. Georg Simmel, Infelices possidentes! (1893, trans. by Mark Ritter and David Frisby), in David

Frisby and Mike Featherstone, eds., Simmel on Culture, 261.

24. Paul Thiel, Berlin prsentiert sich der Welt. Die Treptower Gewerbeausstellung 1896, in Jochen

Boberg, Tilman Fichter, and Eckhart Gillen, eds., Die Metropole. Industriekultur in Berlin im 20. Jahrhundert

(Munich, 1986), 16-27.

25. Georg Simmel, The Berlin Trade Exhibition (1896, trans. by Sam Whimster), Theory, Culture, &

Society 8 (1991): 121.

26. Ibid., 119-20.

27. Ibid., 122.

28. Simmel, Philosophy of Money, 483.

29. Walther Rathenau, Die schnste Stadt der Welt, in Jrgen Schutte and Peter Sprengel, eds., Die

Berliner Moderne 1885-1914 (Stuttgart, 1987), 100.

30. Simmel, Philosophy of Money, 257.

31. The blas people whom Simmel identified as a type thus have nothing to do with colloquial expressions might be associated with this label, say, an arrogant snot, or someone fixated on being cool.

32. Edmund Edel, Neu-Berlin, Grostadt-Dokumente (Berlin, 1908), vol. 50.

33. Simmel, Infelices possidentes! 259.

34. Ibid., 260.

35. Georg Simmel, Die Alpen (1918), in GSG, vol. 14 (1996), 296-97.

36. Simmel, Philosophy of Money, 478.

37. Georg Simmel, The Alpine Journey (1895, trans. by Sam Whimster), Theory, Culture, & Society 8

(1991): 95.

38. Ibid., 97.

39. Eugen Simmel, Spaziergnge in den Alpen (Leipzig, 1880).

40. Georg Simmel, Alpine Journey, 96.

41. This is an allusion to Goethes Italian Journey (published 1816-1817).

42. Georg Simmel, Rom. Eine sthetische Analyse (1898), in GSG, vol. 5 (1992), 303.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at University of Sydney on March 22, 2015

124

JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY / November 2003

43. Ralf Thies and Dietmar Jazbinsek, Berlin-das europische Chicago. ber ein Leitmotiv der

Amerikanisierungsdebatte zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts, in Clemens Zimmermann and Jrgen Reulecke,

eds., Die Stadt als Moloch? Das Land als Kraftquell? (Berlin, 1999), 53-94.

44. Georg Simmel, Rembrandt als Erzieher (1890), in GSG, vol. 1 (1999), 237.

45. Simmel, Rom, 308.

46. Ibid., 306.

47. Ibid., 309.

48. See, for example, the various editions of Griebens Ober-Italien (northern Italy).

49. Typescript Kurt Breysig, in Staatsbibliothek Berlin, NL 125 (Michael Landmann), box 1.

50. Hans Simmel, Auszge aus den Lebenserinnerungen, 226.

51. See, for instance, Simmels letter of recommendation for Bab, July 9, 1910, in Kurt Gassen and

Michael Landmann, eds., Buch des Dankes an Georg Simmel (Berlin, 1958), 107.

52. Julius Bab, Die Berliner Bohme, Grostadt-Dokumente (Berlin, 1904), vol. 2.

53. Ibid., 79.

54. Ibid., 40.

55. Ibid., 3.

56. Bab went uncited, however. See Claude S. Fischer, Toward a Subcultural Theory of Urbanism,

American Journal of Sociology 80 (May 1975): 1319-41.

57. Even if no statistically significant differences between the rural and urban population are discernible

in terms of sex and crime, a change in the form of sexuality and criminality is likely in the city. I presume it

was this change that elicited the rampant fear of sex and crime that Berlin triggered by virtue of its new existence as a major urban center.

58. Hans Ostwald, Dunkle Winkel in Berlin, Grostadt-Dokumente (Berlin, 1904), vol. 1.

59. The greatest sensation was stirred at that time by the report titled Berlins Third Sex (Berlins

Drittes Geschlecht), in which the sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld toured the homosexual scene of the imperial capital, and a volume containing the case histories by a gynecologist writing about female homosexuality. The latter book was banned by the Berlin county court and subsequently confiscated.

60. An instructive example of this early form of urban ethnography is Albert Sdekums study on the living conditions in the tenements (see the third section of this article), which appeared as volume 45 of

Grostadt-Dokumente.

61. Dietmar Jazbinsek, Berward Joerges, and Ralf Thies, The Berlin Grostadt-Dokumente: A Forgotten Precursor of the Chicago School of Sociology, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin fr Sozialforschung,

Discussion Paper FS II 01-502 (Berlin, 2001).

62. Wirth, Bibliography of the Urban Community, 188.

63. In the Working Group on Metropolitan Studies at the Social Science Research Center Berlin

(Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin fr Sozialforschung), my colleagues and I are endeavoring to continue where

Louis Wirth stopped seventy-five years agowith the search for the leitmotifs in Ostwalds project of urban

research. Although a few of the volumes are still frequently cited, especially Berlins Drittes Geschlecht by

Magnus Hirschfeld, the series as a whole was forgotten after World War I.

64. A letter written by Simmel in 1913 and preserved in the Julius Bab Collection of the Leo Baeck Institute in New York indicates that Bab kept Simmel informed of his publications.

65. Khnke, Der junge Simmel, 144. Stefan George (1866-1933), one of the most influential and eccentric lyricists of Wilhelminian society, is meant.

66. Ostwald, Dunkle Winkel in Berlin, 3.

67. Typescript Elly Heuss-Knapp, Staatsbibliothek Berlin, NL 125 (Michael Landmann), box 1.

Another ground rule of this ludic form of sociation was that no one was allowed to bring his idiosyncrasies, problems, and needs along (Margarete Susman, in Gassen and Landmann, Buch des Dankes, 281).

68. Georg Simmel to Stefan George, letter of February 9, 1899. Stefan George archive,

Wrrtembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart.

69. Hans Simmel, Auszge aus den Lebenserinnerungen, 266.

70. Hans Joas, Die Klassiker der Soziologie und der Erste Weltkrieg, in Hans Joas and Helmut Steiner,

eds., Machtpolitischer Realismus und pazifistische Utopie: Krieg und Frieden in der Geschichte der

Sozialwissenschaften (Frankfurt am Main, 1989), 179-210. Sven Papcke, Dienst am Sieg: Die

Sozialwissenschaften im Ersten Weltkrieg, in Sven Papcke, ed., Vernunft und Chaos. Essays zur sozialen