Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Artikel 27

Загружено:

Ilham MustaqimАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Artikel 27

Загружено:

Ilham MustaqimАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Globalisation and urban transformations in the Asia-Pacific region: A review

Fu-chen Lo; Peter J Marcotullio

Urban Studies; Jan 2000; 37, 1; Academic Research Library

pg. 77

Urban Studies, Vol. 37, No. t, 77-111, 2000

Globalisation and Urban Transformations in the

Asia-Pacific Region: A Review

Fu-chen Lo and Peter J. Marcotullio

f Paper firs/ received. March 1998; in final form, J1111e 1999/

Summary.

In the Asia-Pacific context, over the past several decades, economic globalisation

permitted the deepening of intrafirm trade, foreign direct investment and the division of labour

between head offices and their subsidiaries abroad, thus effecting a greater interdependency

between the developed nations and developing nations in the region. The linkages of this

emerging transnational economy are embedded in the region's cities through the world city

formation process and have led to the development of a 'functional city system'. Urban functions,

within the system include, inter alia, production, finance, telecommunications, transportation,

direct investment and even amenity provision. The accumulation of different functions by a given

city provides for the foundation of its external linkage and economic growth and also underlies

transformations in its physical form. While all cities have a variety of functions and play many

roles within the regional economy, dominant characteristics found in cities allow for the

identification of different types including capital export cities, regional entrepots, industrial cities

and amenity cities.

Introduction

During the past few decades, the world economy has experienced structural adjustments

affecting production, resource utilisation and

wealth creation. Cross-border functional integration of economic activities and growing

interdependency among regional economic

blocs are part of a set of processes defined as

'globalisation'. Important elements in the

evolution of the global system are the expansion of trade, capital flows (particularly direct investments) and a wave of new

technologies.

The logic of economic globalisationdriven growth has privileged some regions

and cities over others. In general, the developed world and some developing and newly

industrialised economies (NIEs) have benefited, while many developing countries have

been marginalised. Within developed countries, the centres of finance and advanced

business services as well as high-tech industries have benefited, while cities dominated

by traditional blue-collar employment have

stagnated. Among developing states, the resulting sets of economic arrangements have

benefited Asia-Pacific countries in particular

(World Bank, 1993). (The Asia-Pacific region includes those nations bordering the

South China Sea and the Western Pacific

Ocean excluding Oceania.)

Cities have become nodes in the global

web of economic flows and linkages. Until

Fu-chen lo and Peter J. Marcotullio are i11 the United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies, 53-67 Jingumae S-cbome,

Shibuya-ku. Tokyo 150-8304, Japan. Fax: + 151-3-5467-2324.Email:lo@ias.unu.edu

and Pjmarcu@ias.unu.edu.

0042-0980 Print/ I 360-063X On-linc/00/0 I 0077-35 2000 The Editors of Urban Studies

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

78

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLIO

recently, globalisation has had a dramatic and

positive effect on cities in the Asia-Pacific

region, a result of the emergence of an industrial belt based on the location of manufacturing firms in the major metropolitan centres of

the Asian NIEs, ASEAN, China and Indochina. These cities are becoming the new

sites of global manufacturing production and

are increasingly playing a key role in economic transformations. Indeed, as the recent

financial crisis demonstrated, economic

growth and development among countries

throughout the region is highly dependent on

the international activities that take place

within its cities.

Economic growth, integration and the resultant interdependency has led to the emergence of a regional city system, called the

Asia-Pacific functional city system (Yeung

and Lo, 1996). A functional city system is

a network of cities that are linked, often in

a hierarchical manner based on a given

economic or socio-political function at the

global or regional level (Lo and Yueng,

l 996b, p. 2).

As cities articulate to this system, they undergo

a process of development commensurate with

their dominant economic roles within the set

of transnational flows. While local characteristics play an important part in mediating

globalisation processes, general patterns of

development can be discerned based upon the

intensity of the prevailing currents.

This review essay presents one understanding of urban and regional development in the

Asia-Pacific region through the lens of economic 'globalisation' and the development of

the functional city system. The first section

presents some of the elements of the globalisation process and how they have played out

within the Asia-Pacific region. The second

section describes the world city formation

process (Friedmann, 1986; Friedmann and

Wolff, 1982) as it has impacted cities in the

region. This part of the paper focuses on how

globalisation flows have influenced the

growth of major metropolitan centres in the

region. The third describes the emergence of

an Asia-Pacific urban corridor and the devel-

opment of a functional city system (Lo and

Yeung, 1996; Lo and Marcotullio, 1998). It

presents some patterns of urban development

within the city system. Lastly, the implications

of this mode of growth on the sustainability

of cities will be discussed.

Economic Globalisation

Pacific Region

and the Asia-

Globalisation "implies a degree of functional

integration between internationally dispersed

economic activities" (Dicken, 1992, p. 1 ).

Functional integration is progressing through

increased stretching (geographical widening)

and intensity (deepening) of international linkages. Evidence for the geographical scope of

the processes usually includes the locations of

nodes within the flows. The Asia-Pacific

region has its share of these points in the global

system in the form of urban centres. The

intensity of globalisation is generally given by

a number of trend indicators including trade

and financial flows, foreign direct investments

(FDI), communications (information flows)

and personal and business travel. In the AsiaPacific region, these trends have taken on a

particular character. In this section we describe

changes in the world and regional economy

through the presentation of indicators of

globalisation.

Trade and Financial Flows

World trade has been growing rapidly since

1950 (Table I). From that time to 1992, the

annual average growth rate topped 11.2 per

cent, bringing the net value of global export

trade from US$61 billion to over US$3.7

trillion (UNCT AD, 1994). However, this

growth rate is not only unprecedented, it is also

higher than that of global production. While

in 1950 merchandise exports were 7 .0 per cent

of world GDP, by 1992 global exports accounted for 13.5 per cent of total world output

(Maddison, 1995). A pre-1997 financial crisis

World Bank figure placed world merchandise

exports at 18 per cent of world GDP. No doubt,

the expansion of trade is a defining characteristic of the post-World War II global economy.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

79

GLOBALISATION AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION

Table 1. Regional annual average growth rates of trade (percentages)

Region

1950--60

World

6.5

9.2

20.3

6.1

Developed market economies

North America

EC

7.1

5.1

8.4

10.0

8.7

10.2

18.8

17.0

19.3

7.8

5.9

8.3

Developing countries

South America"

Sub-Saharan Africa

South and south-east Asia

3.1

2.3

4.8

0.2

7.2

5.1

7.8

6.7

25.9

20.6

20.0

25.8

2.2

2.3

-2.0

10.8

1960-70

1970-80

1980-90

"Includes Belgium-Luxembourg, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy,

Netherlands Portugal, Spain and UK.

"lncludes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Paraguay and Uruguay

Source: UNCTAD (1994, Tables l.5 and 1.6, pp. 16-25).

East and south-east

Asian economies

exemplify the world trend in trade (Table 2).

The regional pattern began with rapid increases in Japanese exports, was followed by

trade expansion among the Asian NIEs in the

1960s and has, up until recently, been succeeded by explosive growth rates of trade in

ASEAN countries. While it is true that the

1970s had brought growth in trade to most

countries around the world (average annual

world growth rate in trade was 20.3 per

cent), the Asian NIEs and the ASEAN countries experienced a particularly rapid expansion in their exports and imports (37.2 per

cent for Korea, 28.6 per cent for Taiwan and

28.3 per cent for ASEAN). In the 1980s,

Table 2. National annual average growth rates of trade (percentages)

Country

1950-60

1960-70

1970-80

1980-90

USA

UK

France

Germany

Australia

5.l

4.8

6.4

16.6

0.9

7.8

6.3

9.8

11.4

7.7

18.2

18.4

19.8

19.l

15.9

5.9

5.8

7.7

9.6

6.3

Japan

15.9

17.5

20.8

8.9

Korea

Hong Kong

Taiwan

Singapore

I.4

-0.4

6.5

-0.1

39.6

14.5

23.2

3.3

37.2

22.4

28.6

28.2

15.1

16.8

14.8

9.9

Malaysia

Indonesia

Thailand

Philippines

0.6

-l.l

l.5

4.5

4.3

1.7

5.9

7.5

24.2

35.9

24.7

17.5

8.6

- 1.3

14.0

3.8

19.1

1.3

20.0

12.7

-0.2

-2.0

3.4

4.8

7.2

6.0

18.0

21.7

25.7

2.1

5.1

2.4

China

Argentina

Brazil

Mexico

Source: UNCTAD (1994 Tables 1.5 and l.6, pp. 16-25).

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

80

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLIO

world trade slowed due to the fall in primary

commodity prices and a global recession in

the first part of the decade, among other

factors, but trade for countries in Asia continued to grow. The exceptions were Indonesia and the Philippines. Indonesian trade was

hard hit in the first half of the decade by the

fall in demand for its agricultural and fuel oil

products and political instability depressed

the Philippines' export trade during that period.

Japanese trade with the rest of the AsiaPacific region has been the key to both its

own success and the restructuring of many

neighbouring economies (Shinohara and Lo,

1989). Japanese exports have been increasingly directed to nations in the region. For

example, between 1975 and 1985, the value

of the Japanese products exported to Korea,

Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand increased

by 202 per cent, 226 per cent, 378 per cent,

and 121 per cent respectively (Akita et al.,

1997). By 1987, Japan's trade with the Asian

N!Es had increased so sharply that it was

roughly the same magnitude as its trade with

the 12 countries of the then European Community (Yeung and Lo, 1996). By 1996,

Japan's exports to the world amounted to

US$400.5 billion and over 45 per cent of that

went to Asia (JETRO, 1997).

Notwithstanding its magnitude and rapid

expansion, two important aspects of global

trade during the past few decades were the

growing importance of the service trade and

the growing complexity of international finance. The service sector has increasingly

become an important part of the global economy. It makes up the largest share of gross

domestic product of all but the lowestincome countries. It also accounts for an

increasing share of the gross domestic product of developed nations. By 1993, it accounted for over two-thirds of national

production in these nations (Table 3). The

national importance of the service sector is

also reflected in trade statistics. Beginning in

the 1970s, service trade internationalised and

by the 1980s service industries were growing

faster than any other sector of the world

economy. From 1986 to 1995, commercial

Table 3. Percentage share of service sector in GDP

of G7 countries, 1960-93

Country

USA

UK

France

Germany

Japan

Canada

Italy

1960

1993

58

53

75'

65

52

41

42

60

46

69

61

57

71

65

Percentage

change

1960-93

29.31

22_64

32.69

48.78

35.71

18.33

41.30

t991 figure, from Survey of Current Business,

1993Source: World Bank, World Development

Report (various years).

services trade grew at a rate of 12_5 per cent

per year, while merchandise trade grew

at a rate of 9.5 per cent per year. By 1996,

trade in commercial services was worth

US$ l .2 trillion representing 20 per cent of

total world trade (ADB, 1998). Interestingly,

in the Asia-Pacific region as a whole, the

development of manufacturing production

seems not to have been matched by a similar

level of service-sector development, possibly

because of the use of services from outside

the region

(Daniels,

1998).

However,

service-sector development in cities of the

region has had fundamental effects upon

metropolitan

structure and urban form

(Park and Nahm, 1998; Searle, 1998; Sirat,

1998)_

Another significant trade-related phenomenon has been the development of the global

finance system. While in the past, the world

finance system grew to keep the global trade

system working smoothly, the flows of global finance alone have subsequently taken on

unique importance. Peter Drucker ( 1986) has

suggested that this development represents a

separation of the 'real economy' of the production and trade of goods and services from

the 'symbol economy' of credit and financial

transactions. This separation is significant in

that each 'economy' now operates almost

independently.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

81

GLOBALISATION AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION

The importance of the international finance system can be seen in the absolute size

and increases in foreign currency trade. For

example, in the mid 1980s, foreign exchange

trade exceeded US$150 billion a day, which

annually amounted to 12 times the value of

world trade in goods and services. By the late

1980s, the total was up to US$600 billion a

day, no less than 32 times the volume of

international commercial transactions worldwide (Drucker, 1986; Strange, 1994). Annual

transactions in the Eurocurrency markets

have risen from US$3 billion in the 1960s to

US$75 billion in I 970 to US$ I trillion in

1984 (Strange, 1994). These transactions

have been encouraged by access to a 24-hour

global network of capital markets concentrated in cities such as New York, London

and Tokyo (Sassen, 199l ).

The institutional structure of the emerging

global financial system contributes to its importance. Since the global financial system is

a hybrid of states and markets, it is therefore

not solely within the command of governments. As the 'symbol' and 'real' economies

have separated, the influence of global markets for money has grown and the power of

governments to influence or control these

markets has diminished. The hard lesson of

the Asian crisis is that this part of the system

is vulnerable-the 'Achilles heel' of the

global economy (Strange, 1994). As has been

demonstrated, if confidence in the system

fails, decades of achievement can be wiped

out in a relatively short period of time. The

1980s debt crises pale in significance when

compared with current events in Asia. Further, since the financial system is embedded

in international transactions, 'shocks' in one

place are quickly felt in another. While the

Mexican financial crisis raised questions

for investors and policy-makers, it was the l

997 currency and capital market crises that

pro- vided undeniable evidence of the

intercon- nected nature of the global finance

system. Within a period of days, the stock

markets of Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Hong

Kong, New York, London, Tokyo, Frankfurt,

Paris, New Zealand, Brazil, Argentina and

Mexico re- acted to the ASEAN bursting

bubble. The

current climate within the global financial

system demonstrates that, given impetus, the

reaction on the part of investors to reduce

their exposure, even in well-managed economies, can be translated quickly around the

world. As a result, in 1997, private capital

flows to the emerging markets fell by onethird, with Indonesia, Korea and Malaysia

experiencing the largest declines (ADB,

1998).

Foreign

FD/)1

Direct

Investment

Trade linkages have been strengthened

through growing cross-country manufacturing production processes facilitating intrafirm trade throughout the world and the

region. In the 1980s, transnational corporations accounted for 70-80 per cent of world

trade outside the centrally planned socialist

countries (Feagin and Smith, 1987, p. 3).2

This relationship makes FDI one of the dominating forces of global integration. The

growth of FDl has been an integral part of

the general economic growth in the world

economy (UNCT AD, 1997).

The major channel of FDI is the transnational corporation (TNC). Global TNC activity was relatively unimportant until the

late 1950s. Much of these flows were NorthSouth and were heavily concentrated in resource-based

industries,

transport

and

utilities (Graham, 1995). The total accumulated stock of foreign direct investment rose

from US$14.3 billion in 1914 to US$26.4

billion in 1938 before soaring to reach

US$66 billion at the end of the 1950s (Dunning and Archer, 1987).

Notwithstanding fluctuations, beginning in

the 1960s, FDI flows began to grow at twice

the rate of growth of world gross national

product and 40 per cent faster than world

exports. During the 1970s, total flows of FDI

on an outward basis were less than US$ l 3

billion (Graham, 1995). Then, after 1985,

world FDI flows skyrocketed. In the late

1980s, FDI inflows to countries around the

world grew at the rapid annual average

growth rate of over 24 per cent (Table 4). Jn

subsequent years, the rate of growth of FDI

more than doubled that for world trade. By

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

82

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLJO

"''

,...._

(!)

'

00

c"'

<"l00\0-r--

c--1 vi oci

'

00

c--i oci

.;

"' r-

V)

r -:

u

(!)

8u

'

..c

0....

00

c;

'

'

c :

.9

:::l

-0

c;....0.

c:

.9

o;

c...:.

sc:

'

,J

-c

00

oci

f'l'1-N--

"i -r---ON " "

'' r-: . . .: r-: ..; . . .:

--N

O..i.l.

-o

'

'<!;

r-

<")

'<:tt--O<"lO\

,...._

v;

Cl)

::::>

..... 0

"c':

.9

-o

'

-e

JO

-e

" <" ) ) " ' - """

0\ <"> <"> N <">

< "lN - "' < "l

\000

"'

"o '

;:: u

a c

Ci

u ,

-0

Ve-) i

c-1

(!)

u....

V)

0.

(!)

. ...0.

"'

....

0

:i:i

o

:ac:

t:

.u...

"'

>

00

..,,.

' -\Cl"'"<")'

r'

V)

u:::l

c;

:::l

r"'--\0-('I")

<"l00-0\0

N

00

V)

V)

u

u

0Cl)

(!)

"o '

~

"c':

..;

~

.E

.g

:c

(!)

"...'.

;:;;

ell

E--<

" ' tll

c:

".~'...-~,_ c:

" 'O

(!)

Q.)

~.u...

"'

00

Ir-"-

eoC

~

" '0

0

"'O 0"""

.. ..:c

o :

-0c:

c:

"u'

"'

-0"'

0

0

.....0z_g

o~::~:~'2c:c:.o"'

_g.2.~.... .,, "'

t

..

--

""""" .......

tll

>.

r - "'

C:

c : '3 E oo'- tll

Cl)"""~

--:

0

"'u u

::c"'0 I::

."@ ..;::

O'

ci.

tll-

;g

0

0.

'

::::

'-'

Q >

<.::

r- -0

u00

...., >.o

::':":' I' ..;I'

::i

<..l

Ot--<"l'<:t-

~ ~oo

' '

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

c;o

s-, Cl) r- ~

u.. u.. u

::::

><

tr.J

cs ::E:::::::: ::::

i:"J

"O

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

GLOBALISATION

83

A considerable number of TNCs from a

small number of developing countries, most

obviously some of the Asian NIEs, have

emerged. Among a list of the 1995 top 50

TNCs based in developing economies, 34 arc

home institutions of the 4 Asian NIEs and

China. These 50 firms have total assets ranging from US$1.3-40 million, total sales

ranging from US$366 000 to 36 million and

total number of employees ranging from

7434 to 200 000. Two of them are included

in the 1996 list of Top 100 global TNCs

(UNCT AD, I 997).

Jn the Asia-Pacific region, Japanese

trade grew with the importance of intrafirm

trade among Japanese companies. Many

Japanese TNCs have subsidiaries located in

the region with which they trade parts and

services. In this way, Japanese trade has

strengthened its economic linkages to developing countries in the region. Therefore

the basis for increased Japanese trade with

the Asian NIEs and ASEAN originated and

developed with Japanese FDI. In 1988, the

region's catch of Japanese FDI was 11.7

per cent in I 988 at US$5.2 billion (Yeung

and Lo, 1996).' It is the accumulation of

Japanese FDI and the transfer of knowledgebased intangible assets (for example, production technology, marketing networks,

management systems), which accompanied

these investments that have provided the

impulse for the region's growth (Hatch

and Yamamura, I 996; Lo, 1994). Two

important aspects of Asia-Pacific FDI arc

that it is largely regionally based and that the

manufacturing share dominates total FDI

flows.

The flow of intra-Asia FDI began with

Japanese industrial expansion in the 1960s.

For example, with early liberalisation of

investment regulations in Indonesia, Japan

began investing in the country. The number

of firms increased from 22 in 1967 to 48

in I 970 to 123 in 1975 (Syamwil, 1998,

Table 4). Most recently, with increased

liberalisation in China, Japanese FDI has

flooded that country. In 1994, for example,

there were 636 cases of FDI from

AND TllE ASIA-PACIHC

1996, FDI inflows had reached US$349 billion and FDI stocks reached approximately

US$3.2 trillion, rising from US$ I trillion in

1987, and the sales of TNC foreign affiliates

(US$6.4 trillion) were higher than total

world trade of goods and services (US$6. I

trillion). Cross-border production processes

reflect changes in corporate structures that

arc being pursued t.irough foreign investment

channels.

FDI has been overwhelmingly dominated

by TNCs from developed countries. The resultant investment transactions have been described as mainly limited to a 'triad'

including the EU, North America and cast

and south-cast Asia (focused on Japan) as the

dominant regional blocs (Ohmae, 1985;

UNCTAD, 1997). In I 996, 59.6 per cent of

world FDI flows were among OECD nations.

However, while transnational investment

is primarily concentrated in the developed

market economies, developing countries arc

increasingly playing an important role (Table

5). Cross-investment between the major developed market economics and developing

economics had increased substantially. The

percentage of total global FDI captured by

developing countries had increased from 18

per cent in the mid to late I 980s to over 36

per cent in I 996. Asia has received more

than 60 per cent of FDI flows to the developing world. Recently, China has captured the

role of largest recipient, accounting for a

third of all FDI flows to developing economies (ABO, 1998).

The most discernible impact of the current

financial crisis has been a sharp decline in

private capital inflows to the five affected

countries (Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia,

Korea and the Philippines). Together, they

suffered net private capital outflows of

US$12 billion in 1997, compared to net inflows of US$93 billion in 1996. However,

despite the movement of equity capital out of

the region, in 1997, FDI inflows into these

economies remained at about US$7 billion,

approximately the same as in 1996 (ABO,

1998). This may indicate that the regional

manufacturing production system has not

collapsed.

REGION

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

84

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLIO

\000000

MNOOOO

NNM-

i-.: C'i<io\ci

V)

N-

v)cici....:

Ot--0'\M

C'i

.nr.:<"i<i

"<:I" V)OOV)N

("")

t--C"l\000

O'\\OMO

V)

NN-00

V) C"l

t--"<:l"O'\"<:I"

"<:t"-N

v) o\\Cir.:iri

""'" '

\0

I

V)

o\ ci oO _;

00

'

-:

E0

c:

0

u

u

' "'_:i-.:

\0

'

""'" 00'\0'\C"l N

'

oO

"

Vl

N "<:I" C"l V)

0000V)V)

<i oO v) ci

-r--N-

Oil

c:

c

"@i

:::!:

r- r--

' N

\_C.,..i.<,.."_i<"ici

O i

o l ;;

-<

e-,

E0

c:

~

t:0

"Oi)

GLOBALISATION AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION

Japan alone, slated for the Chinese mainland

(Hatch and Yamamura, 1996).

Japan has maintained a considerable investment position in the region despite its

sagging post-bubble economy. In the early

1990s, Japanese manufacturers, particularly

machine-makers, continued to invest heavily

in the Asia-Pacific. The share of Japanese

manufacturing FDI in Asia has grown from

19.8 per cent in 1990 to 32.9 per cent in 1993

while falling from 43.9 per cent to 37.2 per

cent in North America and from 29.7 per

cent to 18.3 per cent in Europe during the

same period (Fukushima and Kwan, 1995).

Japanese FDI increased sharply in Thailand

during 1993 and 1994 as Casio, Sony, Toyota and Honda expanded their production

capacities. Japanese firms also have recently

increased investments in the Philippines,

Indonesia, Malaysia and China (Hatch and

Yarnamura, 1996).

Recently intraregional non-Japanese FDI

has increased significantly. By the early

1990s, the region experienced increased investments from the Asian NIEs and ASEAN

countries. By 1994, FDI from the individual

Asian NIEs into the region was approaching

the levels of flow from Japan and in the case

of Hong Kong tripled Japanese investments.

During that year, the investments from these

countries were primarily directed at ASEAN

and China (Table 6).

The growth of manufacturing FDI was

related to changes of economic structure

within developing economies in the region.

These shifts were recorded in their export

compositions. During the period 1980-90,

manufacturers' share of exports almost

tripled from 21.8 per cent to 59.8 per cent for

all ASEAN countries. Indonesia's percentage

increase was 15.6 times, while Singapore and

Thailand also made impressive gains (Yeung

and Lo, 1996). In general, the exports from

the Asia-Pacific region increased dramatically after 1985. The four Asian NIEs and

the ASEAN countries accounted for only 9

per cent of world exports in that year, but by

1997 their share had climbed to 14 per cent.

This demonstrates the intimate relationship

between FDI and trade and the importance

85

of capital-exporting countries, like Japan,

Korea and Taiwan to the region's economic

growth.

Communication Networks

The world is in the midst of a 'revolution'

led by advanced digital technologies. Communication networks and interactive multimedia applications are providing the

foundation for the transformation of existing

social and economic relationships into an

'Information Society'. The growth of the

telecommunications industry has been dramatic. In l 994, worldwide, there were more

than 500 million connections to telephone

main lines leaving the 25 leading telecommunications companies with revenues of

US$400 billion and 38 million new subscribers. In that same year, the I 0 largest of

these companies made bigger profits than the

25 largest commercial banks (OECD, 1997).

These telecommunication

technologies

have made markets more transparent and

they continue to steer globalisation processes

as they push down prices for long-distance

transactions. A 3-minute telephone call between New York and London has fallen from

US$300 (in 1996 dollars) in 1930 to USS I in

1997 (The Economist, 1997).

The main drivers for the communications

explosion are infrastructure and new service

development. Most of this development has

been in industrialised nations. The OECD

nations retain 67 per cent of the world's

telecommunication main lines. From 1990 to

1995, OECD nations' telephone main line

provision grew at an annual rate of 3.9 per

cent. By 1995, there was an average of

47 main lines per I 00 inhabitants in these

countries. OECD cellular mobile subscribers

have increased at a compound rate of 45 per

cent per year over the same period and

now reach 71 million users. Similarly, their

numbers of Internet hosts has increased

from 0.6 million in 1991 to 12.4 million in

1996. The current diffusion rate is 12

Internet hosts per I 000 population. TV penetration per household in OECD countries is

90 per cent. In terms of installed PC base, the

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

86

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER J_ MARCOTULUO

.,..,

I'

0

N

'

<') 00 <')

'<t 0 00 <') I'

000000-ID

N I' ID '<t ,

N

'<t

<'>-ll")OO"\

NO\\OOOV")

I' <')

<')

.... .

C')

' '- -'

'N<t

'

00

O\ 00 N '<t <'>

'<t co '<t \0 '<t

OO'<t0\00

-N\0-N

"0 '

t:

a.

\00

.,.., \0

<')

OID

N

\0

.,..,

'

00 ID 0

'<t

I'

'

00

I'

\0

ID

a.

0t"<0l

t:

'

00

.,..,

(;)

< < 10

z z

00

(/)

t.Ll

t:

~

00

t:

0

::i:

z<

00

N

'<t

ll")<'"l000

\O'<tNN

0.

0

( 3

~0

oo-o-

t:

t"<l

Cl

a.

..t.".

<.,l

t:

t"<l

0.

t"<l

.. . . . .

t"<l

t:

:.au

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

GLOBALISATION

AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC

87

REGION

Table 7. Changesin telephone servicesin Asia and

selectedLatinAmericanNIEs

(main lines per 100 inhabitants)

Country

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

Japan

44.1

45.4

46.4

47.1

48.0

Singapore

Hong Kong

Korea

39.0

43.2

31.0

2.4

0.6

8.9

1.0

39.9

45.9

33.7

41.5

48.5

35.7

43.5

51.0

37.9

47.3

54.0

39.7

2.7

0.7

10.0

1.0

0.7

0.2

3.1

0.9

11.2

1.0

1.0

0.2

3.8

1.0

12.6

4.7

9.8

6.7

7.2

11.l

6.9

8.0

Thailand

Indonesia

Malaysia

Philippines

China

Vietnam

0.6

0.2

Argentina

Brazil

Mexico

9.6

6.3

6.6

Percentage

change

1990-94

1.5

0.4

14.7

1.7

2.3

0.6

8.8

21.3

25.0

28.1

95.8

116.7

65.2

70.0

283.3

200.0

12.2

7.4

8.8

14.1

8.1

9.3

46.9

28.6

40.9

1.3

1.3

Source: United Nations (1996, Table 19, pp. 135-144).

US averaged 30 PCs per 100 inhabitants in

1994. Europe's and Japan's penetration rates

are closer to 10 PCs per 100 inhabitants

(OECD, 1997).

In general, developing countries have

lower levels of telecommunications infrastructure development. Low-income economies in the world have an average of 1.97 main

lines per 100 inhabitants. The lower middleincome economies have 9.17 main lines per

100 inhabitants (OECD, 1997). In parts of

developing Asia, however, telecommunications advances are progressing at increasingly advanced rates. In terms of telephone

hook-ups, developing nations in Pacific Asia

have increased their connectivity at a faster

rate than either Japan or Latin American

NIEs (Table 7). Between 1990 and 1994, the

number of main lines per 100 inhabitants

quadrupled in China, tripled in Vietnam and

doubled in Thailand and Indonesia. The percentage ownership of TVs and radios is increasing much faster in these developing

countries than in other developing nations

(Table 8). Further, liberalised markets in

Hong Kong, China, Singapore, Japan,

Malaysia and Indonesia for telecommunications firms are having dramatic impacts on

not only hook-ups, but cellular phone and

Internet services (FEER, 1998).

Transport Linkages

While the major breakthroughs in the transport of goods and services occurred in the

19th and early 20th centuries, modern enhancements-such as large cargo freighters

and jumbo jets-have continued to improve

the movement of people, goods and services.

Since 1980, the number of scheduled international passengers globally has doubled

(Table 9).

More importantly, the expansion and development of commercial high-speed passenger transport have allowed for a rise of

annual distance travelled with personal income. That is, while people from different

classes and societies are spending the same

average amount of time travelling per day,

those with higher incomes are travelling farther." Thus, as world GDP per person has

increased, so has total person kilometre miles

(PKM). For example, total PKM travelled

has increased more than fourfold from 5.5

trillion PKM in 1960 to 23.4 trillion PKM in

1990 and is expected to more than double by

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

88

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER 1. MARCOTULLIO

Table 8. Television and radio receivers (per 1000

persons)

Percentage change

1980-93

Country

1980

1985

1990

1993

Radio

34.4

Japan

TV

Radio

539

678

579

786

611

899

618

911

Singapore

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

311

373

221

506

165

525

21

140

20

99

87

411

22

43

4

55

332

606

234

596

189

946

81

156

38

128

115

421

27

91

9

112

33

100

214

594

185

363

113

199

377

636

272

666

210

1011

106

185

57

145

148

429

381

644

286

671

215

1013

113

189

62

148

151

430

47

143

38

184

42

104

220

672

209

390

150

255

Hong Kong

Korea

Thailand

Indonesia

Malaysia

Philippines

China

Vietnam

Argentina

Brazil

Mexico

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

TV

Radio

93

183

427

124

313

57

134

44

141

30

181

39

103

218

670

207

384

146

254

72.7

32.6

93.0

35.0

49.5

4.6

232.6

234.5

TV

14.7

22.5

29.4

30.3

438.I

210.0

73.6

113.6

850.0

11.8

57.4

24.6

90.3

20.2

68.5

163.2

Source: United Nations (1996, Table 16, pp. 116-123).

2020 to 53 trillion PKM (Schafer and Victor,

1997). This has helped to create a community of global travellers with increasingly

significant social consequences.

The trend in international travel for Asian

passengers reflects these advances. As Table

9 demonstrates, from 1980 to 1994, the number of passengers scheduled for international

services increased, in most cases by twice the

world average rate and faster than the rates

of increase in comparable NIEs in Latin

America.

In general, the increased widening and

intensity of globalisation processes have

been uneven around the world but, until

recently, have affected the Asia-Pacific

region in positive ways. The intensity and

diversification

of international connectivity

among nations within the region and between

those of the Asia-Pacific

region and the

world have created regional interdependency.

Notwithstanding the comments of those that

are less impressed by these trends (for one of

many sceptical views of globalisation,

see

Harris, 1998), the importance of economic

globalisation processes is predicted to increase in the medium to long term (Lo,

1994). The stability of FOi inflows into the

highly affected economies during the 1997

financial crisis is a good sign that the economic base of the region is still on a sound

footing.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

GLOBALISATION AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC

89

REGION

Table 9. Civil aviation trends (scheduled international service passengers, in

thousands)

Percentage

change

Country

1980

1992

1993

1994

1980-94

Singapore

World

163 222

299 612

318424

343 712

110.6

Japan

4499

II 589

11 260

12 700

182.3

9 271

9 929

159.4

2 105

5 633

6 372

7 368

250.0

I 924

922

I 822

997

5 343

2 773

5 081

2 113

6 203

2 932

5 597

2 229

6 775

3 285

6402

2 356

252.1

256.3

251.4

136.3

360

6

4 500

130

4 667

137

4909

137

l 263.6

2 183.3

1300

I 330

2 777

I 787

2 707

3 976

I 661

3 062

3 703

I 999

3 372

3 540

53.8

153.5

27.5

3 827

Korea

8477

Thailand

Indonesia

Malaysia

Philippines

China

Vietnam

Argentina

Brazil

Mexico

Source: United Nations ( 1996, Table 65, pp. 575-589).

World City Formation

The emergence of the functional city system

is defining roles for cities. The factors

that help to explain the emergence and

maintenance of the system encompass the

economic flows among cities integrated into

the system. These include the decisions

made by TNCs to locate their activities

within urban borders and the ways in which

governments promote development. Much

of the economic activity associated with

growth and investment has occurred in the

major metropolitan centres in the region

(Table 10).

Given the type of development in the

Asia-Pacific region (i.e. export-orientation,

manufacturing production with accompanying information and technology-intensive

service development), cities are the spaces of

the most intensive change (Yeung, 1993).

However, other cities within the Pacific

Rim are increasingly being included within

the regional city system (for example, Sydney, Vancouver and Los Angeles). 'World

city formation' is the process by which

the global economy impinges upon cities

and transforms their social, economic and

physical dimensions. At one level, cities

within the region and within the functional

city system are growing more alike. They are

converging (see also Armstrong and McGee,

1985). In this section, we discuss the impacts

of the flows of FDI, trade, information and

people on cities in the Asia-Pacific to demonstrate ways in which they have become

similar.

World City Formation Asia-Pacific

Style

In general, world city formation can be

thought of as the process in which the

world's active capital becomes concentrated

in cities (Friedmann and Wolff, 1982). In

exploring the world city formation process,

many scholars have focused on the role of

command-and-control activities in large urban agglomerations (see, for example,

Sassen, 1991, 1994 ). These authors concentrate on the location of headquarters for

transnational corporations, international institutions, business-services, transport access,

90

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLIO

ll"lOO-t"-\0

o>D>Dirio

N<tll"l<tN

ON\ONt"-'<t'Oll"l\O'<t'

.....

u

o....:C"iC'iC"i..foc-i..fC"i

-0

O -<t<"l-

:::l

O-N-

.~<;;

C1)

-0

"e'

--.-V)-N'tj-1.f)O\'-.:::f'"

ll"ll"-<"lt"-0\0\00-V)

V)

ll"l-NN-<"IOON

-

CJ

V)

c:

.~

~

:;

0..

0..

' '

<')

V) V) <')

<')

O\-ll"lO\Nll"lO\O\ON-ll"lt"-000\\0NOOO

V)

'

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

GLOBALISATION

91

firms. Telecommunications and transport infrastructure were among the top seven determinants of investment location decisions

(FEER, 1997).

Central governments have been important

to the development of urban infrastructure.

Asia-Pacific governments have taken note of

the World Bank's (1994) conclusions that

infrastructure investment was positively correlated with economic growth and have acted

accordingly.5 Table 1 I demonstrates investments in infrastructure among economies in

the region compared to other fast-growing

economies in South America. While there

has been progress, infrastructure gaps have

been one of Asia's bottlenecks. Because of

rapid growth, Asia-Pacific nations have had

a shortfall in infrastructure investment. Most

countries in the region have grown by between 7 and 8 per cent since the 1980s, but

they have only invested about 4 per cent of

their GDP in infrastructure resulting in a 2-3

per cent investment gap (Thornton, 1995).

Although, on the whole, national infrastructure investment has not been sufficient to

keep up with demands country-wide, much

of the infrastructure investment has been

concentrated in major metropolitan centres,

which has intensified the effects of globalisation processes in those spaces. Further, there

has also been a specific and similar set of

urban infrastructure developments across

Asia-Pacific cities.

Whereas the emphasis in Latin America

and in Eastern Europe has been on the privatisation of existing infrastructure facilities,

Asia has been investing heavily in, inter alia,

new transport

and telecommunications

projects (OXAN, 1998). These investments

were made to cope with rapidly growing

global traffic. One popular project has been

the large futuristic airport, such as the recently opened Chek Lap Kok airport in Hong

Kong, Kansai airport in Osaka, the Seoul

Metropolitan Airport and Nong Ngu Hao in

Bangkok. Indeed, the concept of the 'Pearl

River delta' could be marketed only because

of the plethora of new airport openings in the

region. Locations include Hong Kong, an

AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC

population size, research and education facilities, and convention and exhibition functions (Friedmann, l 986; Rimmer, 1996).

This focus, however, limits the numbers and

types of cities included as 'world' or 'global'. On the other hand, a number of scholars

have also included the role of industrial production activities and trade (Feagin and

Smith, 1987; Lo and Yeung, 1996a). Regional and world cities include those that

have become major centres of manufacturing

and service-related activities.

The world city formation process implies

that, in order to be effective in global and

regional economies, cities have undergone

physical

restructuring.

Some important

physical characteristics

that are part of

the world city formation process include

the development

of transport facilities

and communication infrastructure (including

teleports). Many times these are incorporated

into public projects financed by governments. At the same time, the private sector

is also heavily involved in the production

of urban mega-projects and 'prestige buildings', usually as part of inner-city development (Olds, 1995). These developments

often include land reclamation.

Further,

urban transformations include the development of R&D complexes just outside the

city's boundary.

The term 'infrastructure' includes a variety

of public structures such as utilities (power,

telecommunications,

piped water supply,

sanitation and sewerage, solid waste collection and disposal), works (roads and major

dams and canal works for irrigation and

drainage) and transport edifices (urban and

interurban railways, urban transport, port and

waterways and airports) (World Bank, 1994).

In developing countries, these investments

account for up to 20 per cent of total investment and 4 per cent of their GDP (World

Bank, 1994). Good quality infrastructure is

not only conducive to economic production,

but is also important in attracting investment

(Peck, 1996). In a survey by the Far Eastern

Economic Review, infrastructure issues were

considered crucial to investment decisions by

REGION

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

92

FU-CHEN

LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLIO

.,., r-

'

0N0 "..'.-;

0\

"'

"<!" 00

<'"> !")

N

!")

o.,O

C--'<tr--N

eo

..,

c :

Vj

~. 9~

<.)

'1" 00

' c

o

u

<.) .....

ci

ci

~

0 00

-

NO

N-

00 "

.....

'1"

00

"0"'e"-'"'.",..""''",

0g00gg

.,..,

'

"0' "N'

\

00

N

-o

N

..f

....

"

!")"'

ci

..f

V"lt"\0 N

\0 N

'

u ..c:0:I

-o ""'"

00

'<t 00 ..f~..f_;

.....

"'

"<!" 0\

0

N

00

!Ci ei ~~

N

N

'

o .

-

'

" ;!:"'

.c..... '-

CO N

_q ~

~ s

.M~

'

UJ 5

"<!"

V'l

-Ne-N -o

'""'"

.,.., .,., -.

"r '0

<'"l N

f'i

<.)

., c"'

'

., .,

r - .

'<t

'<t

V"lNN

N -

'

..;-

8.,. 0"' V1N

"' ""'" 00 00

.,

.,.0.

,

ONO

-N-

V)

"' ""'" ' "'

' ~ '_ ;

M.,..,

'.,6..,

u

ONN

"'

v~-o

o.

8

N

"<! "

cE

V1

0\

-1""'--Mt"-I

3~

0., .,

00

r-, r.,.., !")

.,..,

"' -N-

(")

0V"l

"' !")

~-N

..c:

....

c..

<.)

CJ ..0

:::>

-0

0

'

..f

00 r<i

00 00

''

-<.) E:::>

f-

000

00

' . . .

; .: : u

c

r-:

"'2" I:"

<'"> -

.....

)0

0""

2'" \

0\

0 MN

000

N

N V10

r>

-N

., . , ' 00

0 0 00 0

-!"'l("'i\O

O\t"-N"<t

C\r"'N\O

<'"l N N

N

00

r-

.,..,

00

r-

.....

0\0-0<'"l

""'"v

r-. \0 V)

f'i

N0\\00

"'

cc:I

0

'

r-a-.

"c

u

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

GLOBALISATION

AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC

airport capable of receiving large aircraft in

Shenzhen, a modern new air facility in

Macau, another in Zhuhai (city adjoining

Macau) and approval from Beijing for one in

Guangzhou

(Vittachi,

1995).

Before the

Asian financial

crisis of 1997, 11 new airports were planned for opening within the

next l 0 years in different cities throughout

this area (Yeung,

1996). Those cities that

already have large airport terminals are in the

process of upgrading them. Cities such as

Taipei and Singapore already have modern

facilities, but are planning for future expansions (Japan Development Bank, 1996). Singapore, for example, plans to enlarge Changi

airport, so that it can handle over two and a

half times more airplane take-offs (360 000)

a year.

Asian

countries have made significant

strides in providing road and rail transport

access to large cities. During the

period

1965- 75 annual highway usage increased at

the rate of l 0. 7 per cent and annual truck

tonnage increased by 7 .19 per cent, while the

growth rate of the region was only 4.7 per

cent (Yeung,

l 998). In road and rail transport, Hong Kong and Japan have been high

infrastructure investors. During the post-war

years Japan successfully

pioneered highspeed trains (Shinkanseni that revolutionised

short-distance

travel in the country. Between

l 990 and 1993, Hong Kong truck tonnage

grew at 15.3 per cent annually and passenger

growth grew by 8.9 per cent (Yeung. 1996).

This represents the results of heavy investment in roads. Both Tokyo and Hong Kong

have also invested heavily in bridges. In

l 994 alone, Hong Kong awarded six 'considerably sized' bridge contracts to international

construction

conglomerates

(compared with

one awarded during that year in all of

France) (Thornton,

1995), including the Tsing Ma Bridge-the

biggest railway suspension bridge in the world. Hong Kong recently

finished a US$20 billion transport project

and is committed to spending another US$30

billion on future transport infrastructure over

the next 5 years (Leung, I 998).

Other nations in the region have also invested in road and rail transport infrastruc-

REGION

93

ture to connect their cities. South Korea

started its transport investment

with the

Seoul-Pusan,

Seoul-Incheon

and DaejonJeonju express highways in the late 1960s

and by 1990 had completed over 1551 km of

expressways (Hong, 1997). South Korea has

also been working on a high-speed railway

system (Thornton, 1995). Kuala Lumpur in

Malaysia recently finished the first line of an

urban light rail system and their Renong

group completed

an 800-km North-South

Highway for US$2.3 billion in 1994. Renong

may also build a US$725 million high-speed

'tilting-train' that would significantly reduce

travelling

times

between

Rawang, Kuala

Lumpur and Ipoh, 174 km to the north

(Jayasankaran,

1997).

The volume of trade generated by the region has facilitated the development of the

world's largest cargo pons. Most of the import and export traffic flows through selected

cities. Of the world's 'top 25' container pons

in 1992, 12 are located in the region; these

include (in rank order) Hong Kong(!),

Singapore (2), Kaohsing (4), Pusan (5), Kobe

(6), Keelung (10), Yokohama (I I), Tokyo

(14), Bangkok (19), Manila (21), Nagoya

(24) and Tanjung Priok (25) (Rimmer, 1996).

In I 984, the league of largest pons was

headed by Rotterdam and bi-state New York/

New Jersey pons, but by 1992 Hong Kong

and Singapore

had moved up to first and

second

posrtions respectively

(Rimmer,

1996). As entrepots,

both Singapore and

Hong Kong represent extreme cases of tradecity nexus. Singapore's exports of goods and

non-factor services were I 90 per cent of its

GDP in 1990 and, during the same year,

Hong Kong's exports were 137 per cent of

its GDP (World Bank, 1992). Eighty per cent

of Korea's imports and exports go through

Pusan (Thornton, 1995). In Jakarta, Indonesia, the 1989 value of the city's exports

accounted for one-third of all Indonesia's

exports (excluding oil and gas) and the city's

share of trade has been increasing since

1986. During 1989, 50 per cent of all imports

to the country moved through

the city

(Soegijoko, J 996).

94

FU-CHEN

LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLIO

Another type of urban development

project encouraged by the world economy

is the construction of high-speed information

transmission infrastructure. This is particularly important for service-sector growth

and maintenance. As mentioned previously,

although the region is lagging behind the rest

of the world, business services are of growing importance in selected cities (Edgington

and Haga, 1998). In general, large cities

in the region are the best providers of

telecommunication

services among the

nations of east and south-east Asia. Two to

three times the percentage of urbanites enjoy

telecommunications links in the cities of

Bangkok,

Manila, Jakarta and Shanghai,

compared with the inhabitants of the smaller

cities and the rural areas in their respective countries (Japan Development Bank,

1996).

In some Asian cities, information technologies have taken on special importance.

Singapore has attempted to restructure its

economy towards the creation of an information city." A 1991 government publication

set out the key role of the information economy in meeting the city-state's needs. The

city-state is aiming to make itself a hub of

communications, finance and travel. Information technology is at the core of plans for

the city's future (Perry et al., 1997). The

Teleport project in Tokyo, less than 6 km

from downtown, was planned as an information and futuristic city. The estimated construction cost of the area's infrastructure

alone is approximately US$20 billion (TMG,

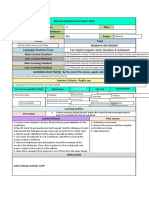

1996). Malaysia is holding to its promise to

develop a 'Multimedia Super Corridor', Cyber Jaya, that will stretch from Kuala

Lumpur 50 km to the south, ending at a new

international airport. It will be connected to

both the airport and the capital via several

forms of transport (see Figure 1 ). Despite the

nation's current fiscal situation, the project is

still moving ahead (Hiebert et al., 1997).

This project is envisaged as a setting for

multimedia

and information-technology

companies and is being promoted through

government incentives.

An additional information-related type of

development that is changing the urban region's landscape in the Asia-Pacific region is

the construction

of large R&D facilities.

Asian cities have invested in R&D complexes that are typically located outside the

city core. In Japan, the government has encouraged the construction of entire technoIogicall y advanced cities or 'technopolises'

such as Tsukuba Science City located northeast of Tokyo (see below). Taiwan used this

model to create Science Park, a new R&D

and high-technology

manufacturing

centre

located in Hsinchu outside Taipei.

Location decisions for TNCs not only include consideration

of the amount of infrastructure, but also of its type and quality as

particular industries have specific requirements (Peck,

1996). Asia-Pacific

governments, in efforts to provide incentives to

firms, have developed

'industrial parks' at

the outskirts of their cities. Much of this

development has been concentrated in and

around major metropolitan cities in the region (Table 12). In Singapore, Taipei and

Seoul, industrial parks have operated with

success, prompted and supported by government and private investments.

One important and controversial device to

stimulate exports and foreign investment has

been the development

of export-processing

zones (EPZs). An EPZ is a relatively small,

separated area that is designated as a zone for

favourable investment

and trade conditions

(compared with the host country). In effect,

they are export enclaves within which special

concessions

apply-including

extensive incentives and often exemptions from certain

kinds of limiting legislation.

The government

provides the physical infrastructure necessary

for industries. EPZs are set up for manufacturing. While some EPZs have been incorporated into airports, seaports or commercial

free zones located next to large cities, others

have been set up in relatively undeveloped

areas as part of a regional development strategy. Asia contains 60 per cent of all EPZ

employment in developing countries. Hong

Kong and Singapore are zones of intensive

export-processing activities concentrated in a

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

GLOBALISATION

95

AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION

/\

'<, _ _.....-,

.I

MALAYSIA

.\

c:

Kuala

Lumpur

''\.

'

\'

;

"-- 1.'1:

'

1:

1:

1:

<

,

-_/-;'fr ..r'l,-"!

Cyber

Jaya

pI"1: { Putrajaya j ,

;;1:,

r:

~')

'

-,

'---- _,.._I-~":..:-~

'

t: )

......

1\~

1\~

\ \'

1:

/

/.

ERL

KUA

Express Rail Link

Kuala Lumpur International

Airport Expressway

NS

North-South Expressway

"-

Kuala Lumpur'')

International /

Airport

,

" '".j

I

,./

number of industrial estates. In 1986, total where with the exceptions of Mexico and

employment in such zones was 89 000 and Columbia, EPZs have not played a prominent

217 000 persons respectively. The other ma- role in the industrialisation process.

jor concentrations are in Taiwan (80 469 emApart from infrastructure, the public and

ployed in 4 EPZs), Malaysia (81 688 private sectors in Asia-Pacific cities have

employed in 11 EPZs), South Korea been involved in redevelopment efforts.

(140 000 employed in 3 EPZs) and the Changes in the global economy are inducing

Philippines (39 000 employed in 3 EPZs) cities throughout the world to look at large(Dicken, 1992). This type of development is scale development projects as a way to rein stark contrast to that of South America structure land uses and stimulate the local

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

96

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLIO

Table 12. The location share of industrial parks

around selected Asian cities, 1993

Percentage share of

total industrial parks

up quickly"," According to the Tall Building

Council, in 1986, the 10 tallest buildings

were all in the US. In 1996, 4 of the top IO

were in Asia (Petronas Towers, Malaysia;

Central Plaza, Hong Kong; Bank of China

Extended

Tower, Hong Kong; Shun Hing Square;

City

Inner city metropolitan area

Shenzen) (Gebhart, 1997). Typically these

projects are usually conceived of as landKuala Lumpur

0.5

8.1

marks to "symbolise the prosperity of the

Bangkok

23.6

Manila

1.9

70.2

city ... and embody the hopes and lofty ideBuilding

Tokyo,

completed

in 1985,

Jakarta

9.7

66.9

als

of the inpeople".

8 The

Mitsui New

No. 2is

Source: Japan Development Bank (1996).

regarded as the first built in Asia. Since then

Manila has completed a 32-storey Stock Exchange Centre in 1992, which is run by an

economy (Amborski and Keare, 1998). electronic nerve centre able to monitor the

For example, in many cities in developed and internal conditions of the building by regulatsome developing countries, large, well- ing air conditioning and lighting. Seoul's

located areas previously occupied by railroad Sixty-four Building is also one of similar

facilities, related transport and industrial uses design and significance.

have been left abandoned as more goods are

An aspect of many Asian projects is that

now shipped in containers from a smaller they are on 'reclaimed' land. For example,

number of ports and terminals. These much of the central-city area of Singapore

deserted areas represent opportunities for resince 1960s has been reclaimed, including

development and have helped to advance the East Coast area, which over the past two

megaprojects, which have come into vogue decades has seen the arrival of new commerat the end of the 20th century. Over three cial and business centres such as Marine

dozen such projects have been identified Parade. The Kansai, Chek Lap Kok and

around the world (Olds, 1995). In Tokyo, for Seoul airports are all built on reclaimed land.

example, over the last decades the four Tokyo has been expanding through landfills

largest redevelopment

projects were the along the Tokyo Bay since the 1960s to

Tokyo Metropolitan government office provide sites for its booming industries and a

building in Shinjuku, the Ebisu Garden new airport. The Haneda airport, only 15 km

Plaza, the Tokyo International Forum and the from the city centre, was originally built as

Tokyo Teleport. These projects represent a an international facility, but has only supredevelopment effort that has been compared ported a domestic role after the opening of

to the rebuilding undertaken after the great Narita. The demand for space in Hong Kong

Kanto earthquake in 1923 and reconstruction

since the mid 19th century has necessitated

after the 1945 World War II bombings. The

land reclamation from its deep-water harcity has been expanding (more quickly dur- bour.

ing the 1980s) in all directions possible: up

World city formation is a continuing and

to new heights, out to the edges of the Kanto

varied process. The few examples of related

plain; off into Tokyo Bay and down below

urban physical transformations in the Asiathe ground (Cybriwsky, n.cl.).

Pacific are presented as common features. A

These publicly and privately financed

description of this process, however, neither

megaprojects often include high-profile provides a prediction as to whether a particu'prestige' buildings to portray their status. As lar city will continue to participate in globalone architect suggested, "many Asian coun- isation-driven growth in the future, nor does

tries see the tall building as a device to move it make possible the determination of a dethem quickly into the 21st century, to catch fined development path for all cities. The

GLOBALISATION

97

works within the Asia-Pacific region, the

emergence of a large urban corridor stretching between Tokyo and north-east China, via

the two Koreas, to Malaysia, Indonesia and

the Philippines, makes up the east Asian

regional system. The large urban corridor

consists of a set of smaller-scale urban corridors including the Pan-Japan Sea Zone, the

Pan-Bohai Zone and the South China Zone,

among others (Figure 2). Choe ( 1996) provides an illustration of a mature transnational

sub-regional urban corridor, in which an inverted S-shaped 1500-km urban belt from

Beijing to Tokyo via Pyongyang and Seoul

connects 112 cities with over 200 000 inhabitants each into an urban conglomeration of

over 98 million people (Figure 3).

Cities networked into the functional city

system in the Asia-Pacific region have not

developed uniformly. The demands of the

emerging city system in the region have been

different for each city depending on a variety

of factors, but predominantly upon the economic functions performed. Those cities that

are on the top of the urban hierarchy include

the major capital exporters. Within these cities, business firms play important commandand-control roles within the world and the

region (for example, Tokyo, Japan, and to a

lesser extent Seoul, Korea, and Taipei, Taiwan). These cities are developing differently

from the major industrial FDI recipients (for

example, Jakarta,

Indonesia,

Shanghai,

China, and Bangkok, Thailand). Further, two

entrepots (Hong Kong and Singapore) have

demonstrated a level of cross-border development not experienced as intensely as other

metropolitan centres. Lastly, some cities in

the system have been developing as 'amenity' cities. These, urban centres are taking

steps to enhance their ecological environments in such a way as to attract investment

and economic activity.

AND THE ASIA-PACIFJC

next section presents generalised patterns of

differentiated development among sets of cities in the region. The categorisation is not

meant to be exhaustive, but rather demonstrates the ways that international functional

networks have impacted city growth and development differently.

The Regional Functional City System

Although globalisation connotes an increasingly homogenised world, and has led to the

use of such labels as 'global village', 'global

market-place' or 'global factory', claims of

movements towards seamless urban space

are oversimplifications. The 'global city'

concept connotes a uniform development that

obscures the multifaceted dynamics of

growth for cities in the world city system.

Thus, rather than focus on the singular form

of 'global cities', we present world city formation as a multifaceted process. Economic

interdependency and government interventions have also allowed for divergence in

urban growth and development patterns

among cities in the region. As cities outside

the Asia-Pacific region, as defined in the

beginning of this paper, incorporate into the

regional city system, they too take on unique

and important functional characteristics. As

the functions of cities within the regional

system vary, so do their development patterns.

Although directed in many ways, the

government-backed

pursuit of growth

through the free market has privileged the

process of capital accumulation. Many city

public officials have formed coalition with

either land-based entrepreneurs or business

conglomerates. The weak tradition of local

autonomy and lack of decentralisation among

nations in the region have inhibited the formation of intermediate institutions and organisations for tighter regulation. Hence,

growth has followed the broad outlines delimited by the particular unique functional

role of the city in the regional and global

economy (Kim, 1997; Lo, 1994; Lo and Marcotullio, 1998; Yeung and Lo, 1998).

Among a variety of developing urban net-

REGION

Capital Exporters (Post-industrial Cities)

The post-industrial city is dominated by the

processing of information and knowledge

(Savitch, 1988). Tokyo, Seoul and to a lesser

98

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLIO

Population (million)

20

. 15

.. 10

..

.6

.. 3

1

CHINA

Xi'an.

Chengdu.

Chongqing.

'

->:

PACIFIC OCEAN

''

'Myanmar

..

-, ...... ..'-. -----

@ Urban corridor

CS) GrO'Nth triangle

. -,_-' LAO~:

I

",:,-~_,

Q Natural economic region

PHILIPPINES~

.. '.,:",

11,

:

:

THAILAND

Manila

\_,

j>

'

. ~cf~\0

fto%'

INDONESIA

s-:

OCl~C::::;;:=::J"~

C::)

500

' I '

I

Turmen River Delta Growth Triangle

II

The East Sea Rim (Sea of Japan} Economic

Regton

Ill

BESETO Urban Corridor

IV

Bohai Rim Economic Region

V

Yenow Sea Economic Region

VI

Yangzi River Urban Corridor

VII

Southern China

Growth

Triangle

VIII Taiwan-Fujian Growth Triangle

IX

Pearl River Oeha Growth Triangle

X

Baht Economic Region

XI

Northern Malaysian Growth Triangle

XII SUORI GrowthTriangle

XIII JABOTABEK Urban Corridor

XIV Oavao-Manado-Sabah Natural Economic R ion

1000 km

I

Figure 2. Urban corridors in east Asia. Source: Choe (1998, Figure 7.3).

extent Taipei exemplify the Asia-Pacific

style of post-industrial development. Sassen

( 1991) has identified the economic and social

order of 'global cities', of which New York,

London and Tokyo are examples. By now,

the argument is familiar to the reader. These

cities are the sites of concentrations of TNC

headquarters, multinational

banks and producer and business services. In Tokyo, employment in manufacturing is decreasing and

employment in the service sector is increasing (Honjo, 1998). It houses a high concentration of central management

functions

(CMFs), research and development firms and

government agencies within Japan. At the

same time, the city is expanding, leaving

inner-city workers with longer commutes

as many of the jobs remain in the innercity area.

Like Tokyo, Seoul has a disproportionate

GLOBALISATION AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION

99

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

100

FU-CHEN LO AND PETER J. MARCOTULLIO

share of the national population (23 per cent

in 1995). Service and high-tech activities are

also highly concentrated within the Seoul

metropolitan area. In 1992, 57 per cent of the

total industrial establishments and 51 per

cent of their workers were located in the

Seoul Metropolitan Area (Hong, 1997). All

of Korea's TNCs are based in the capital city

and enjoy close contact with the central

government, a necessary condition for Korean business deals. While new 'downtowns', across the Han River have been

created by moving the various back offices

into locations close to the new towns of

Pyongchon,

Sanbon and Bundang, Seoul

City retains the most important control-andmanagement functions (Kwon, 1996, 1998).

Also, like Tokyo, the amount of inbound FOi

is small compared to that of outbound flows.

In the single year of 1996, outbound flows of

FOi from Seoul reached US$4.2 billion.

Compare this with US$6.25 billion, the total

accumulated stock of inbound FOi in the city

as of 1996.

These relations take on specific forms in

the urban landscape. Both cities have con-

centrations of large megaprojects, particularly those with large high-rent residential

and commercial spaces, R&D centres, and

recreational/entertainment facilities for the

upper-income

service-sector

employees.

Teleports for the smooth transmission of information and gleaming 'intelligent' buildings housing banks and other important

financial institutions are developed in central

business districts. Nodal clusters of spatially

differentiated economic activities have appeared. This multicentric structure is seen in

Tokyo (Figure 4) where areas such as

Shibuya, Ikebukuro, Ueno and Shinjuku each