Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Prevalensi

Загружено:

Maria AprilianaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Prevalensi

Загружено:

Maria AprilianaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:(2):142-146

A survey of dental and oral trauma in south-east

Queensland during 1998

EB Wood,* TJ Freer*

Abstract

Background: This project investigated the aetiology

of dental and oral trauma in a population in southeast Queensland. The literature shows there is a lack

of dental trauma studies which are representative of

the general Australian population.

Method: Twelve suburbs in the south-east district of

Queensland were randomly selected according to

population density in these suburbs for each 25th

percentile. All dental clinics in these suburbs were

eligible to participate. Patients presenting with

dental and oral trauma were eligible to participate.

Results: A total of 197 patients presented with

dental/oral trauma over a 12 month period. The age

of patients ranged from 1-64 years whilst the most

frequently presenting age group was 6-10 years. There

was a total of 363 injured teeth with an average of

1.8 injured teeth per patient. Males significantly

outnumbered females in the incidence of trauma.

Conclusions: The highest frequency of trauma

occurred in the 6-10 year age group. Most injuries in

this group occurred while playing or riding bicycles.

In the next most prevalent trauma group, 16-20 years,

trauma occurred as a result of fighting and playing

sport. Overall, males significantly outnumbered

females by approximately 1.8:1.0. The majority of

injuries in the deciduous dentition were to periodontal

tissues. In the secondary dentition most injuries were

to hard dental tissue and pulp.

Key words: Trauma, aetiology, epidemiology.

(Accepted for publication 18 January 2001.)

INTRODUCTION

The majority of dental trauma studies, particularly in

Australia, have specifically focused on patients

presenting to school dental services, casualty

departments of hospitals or after hour clinics.1-4 These

sub-populations represent a small portion of the

general Australian population. Davis and Knott5 in

1984 studied patients presenting with dental trauma to

members of the Australian Society of Endodontology,

Australia-wide. They found that the group most at risk

of dental trauma was the 6-12 year olds and this was in

agreement with other international studies.6,7

*School of Dentistry, The University of Queensland.

142

Stockwell established a rate of 1.7 per cent per

year in a population of 66 500 children aged 6-12 years

presenting to a school dental clinic with dental

trauma. However, only injuries to anterior permanent

teeth were recorded.1 Another Australian study by

Burton et al.2 found a prevalence rate of 6 per cent

of dental trauma in 12 287 secondary school students.

A contrasting study in England, by Hamilton8

established a 34 per cent prevalence rate of dental

trauma in 2022 secondary school students. This large

difference between the Australian and English studies

may be attributed, in part, to the different injuries and

teeth included in each study and the relatively low

response rate of 52 per cent in the Australian study.

The literature shows that there is a lack of dental

trauma studies which are representative of the general

Australian population. This survey studied the aetiology,

gender and age distribution of dental/oral trauma in a

diverse south-east Queensland population. Subjects

were recruited from inner city suburbs and rural areas

of south-east Queensland presenting to a sample of

public and private dental clinics.

M AT E R I A L S A N D M E T H O D S

Twelve suburbs in the south-east district of

Queensland were randomly selected according to

population density three suburbs from each 25th

percentile. All dental clinics listed in the Yellow Pages

in these suburbs were eligible to participate in the study.

Patients who presented with trauma to any dental or

supporting structure of the mouth were eligible to

participate. They were asked to complete one section of

a two part self-administered questionnaire which

elicited demographic information as well as information

about the nature of the accident or mishap which

caused the injury. The second section contained

questions about the nature and severity of the dental

and oral injuries and was completed by the treating

dentist or therapist.

Parents or guardians completed the questionnaire for

their children and this was noted on the consent form.

Information about pre-existing dental trauma as a

result of previous accidents was also collected in this

survey.

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:2.

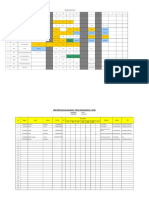

Table 1. Age distribution of dental injury patients

Age of patient (years)

Number of males (%)

1-5

6-10

11-15

16-20

21-25

26-30

31-35

36-40

41-45

46-50

51-55

56-60

61-65

Totals

22

33

24

30

7

4

1

2

1

1

Number of females (%)

(17.5)

(26.2)

(19)

(23.8)

(5.6)

(3.2)

(0.8)

(1.6)

(0.8)

(0.8)

18

22

11

9

3

1

3

1

71

1 (0.8)

126 (64)

The types of injuries were classified in accordance

with the three tier classification of Andreasen:9 (1)

injury to hard dental tissues and pulp; (2) injury to the

periodontal tissues; and (3) alveolar fractures. Injuries

in each of the three groups were further classified into

six categories. Group 1: (a) uncomplicated enamel

fracture; (b) uncomplicated enamel and dentine

fracture; (c) crown fracture (pulp exposed); (d) crown

and root fracture; (e) crown and root fracture (pulp

exposed); and (f) root fracture. Group 2: (a) concussion;

(b) subluxation (loosening but not displaced); (c)

extrusion; (d) lateral luxation; (e) intrusive luxation;

and (f) avulsion. Group 3: (a) comminution of the

alveolar socket; (b) fracture of the alveolar socket wall;

(c) fracture of the alveolar process with and; (d)

without involvement of the tooth socket; (e) fractures

of the mandible or maxilla with and; (f) without

involvement of the tooth socket. All 18 injury

classifications were also represented by a diagrammatic

illustration of the type of injury in the questionnaire to

avoid confusion. Injuries to the total dentition were

recorded including injuries to both primary and

permanent teeth.

Recruitment of patients was over a 12-month period.

A total of 197 patients from 49 clinics provided a

completed questionnaire and were included in the

analyses. One patient presented to the same dentist on

two separate occasions with dental injuries arising from

two independent accidents and was treated as two

cases. Whilst the dentist at the clinic was responsible

for recording all patients presenting with dental trauma

it was uncertain how accurately the data were recorded.

Total number (%)

(25.4)

(31).4

(15.5)

(12.7)

(4.2)

40

55

35

39

10

4

2

5

2

1

3

(1.4)

(4.2)

(1.4)

(4.2)

(20.3)

(27.9)

(17.8)

(19.8)

(5.1)1

(2)

(1)1.

(2.5)

(1)1.

(0.5)

(1.5)

1 (0.5)

197 (100)1.

(36)

Chi-square tests were used to determine if any

significant differences existed between the proportions

of patients in each variable category investigated.10

R E S U LT S

Data were collected for those patients who presented

with dental or oral trauma and whose ages ranged from

1-64 years. The most frequently presenting age group

was in the 6-10 year range for both males and females

(Table 1).

There was a total of 363 injured teeth, with an

average of 1.8 injured teeth per patient. Most patients

injured one or two teeth per accident 37.6 per cent

and 37.1 per cent respectively. Three or four teeth per

patient were injured in 7.1 per cent of accidents, while

five teeth per patient were injured in 2 per cent of

accidents. Six teeth per patient were injured in three

patients and only one patient injured seven teeth in an

accident (Table 2).

The most common activity at the time of the accident

for both males and females was playing, 23.8 per cent

and 21.1 per cent respectively. Males and females

generally differed in their activities at the time of the

dental injury. There were more injuries sustained

during walking and running activities for females,

compared with injuries sustained through playing

sports in males (Table 3).

Males significantly outnumbered females in incidence

of trauma by a factor of 1.8 (126 males, 71 females,

p<0.001). This trend was reflected in all types of

trauma, except for trauma as a result of a car collision,

swimming and drinking/eating. The proportions for

Table 2. Sex distribution of patients with dental injuries to the primary and secondary dentition

*Primary dentition

Number of teeth

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

11

13

1

4

Male

(%)

Female

(%)

(35.5)1

(41.94)

(3.2)1

(12.9)

7 (43.8)

9 (22)1.

(6.5)

Secondary dentition

Male

(%)

38

30

8

6

3

(44.2)

(34.9)

(9.3)

(7)1.

(3.5)

1 (1.2)

Female

(%)

Male total

(%)

18 (36)

21 (42)

5 (10)

4 (8)

1 (2)

1 (2)

49

43

9

10

3

2

1

(38.9)

(34.1)

(7.1)

(7.9)1

(2.4)1

(1.6)1

(0.8)1

Female total

(%)

25

30

5

4

1

1

(35.2)

(42.3)

(7)1.

(5.6)

(1.4)

(1.4)

Total

(%)

74 (37.6)

73 (37.1)

14 (7.1)1

14 (7.1)1

4 (2)1.

3 (1.5)1.

1 (0.5)1.

*Primary dentition includes patients injuring only primary dentition and patients injuring both primary and secondary dentitions in one accident.

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:2.

143

Table 3. What patients were doing at the time of the injuries

Activity

Playing

Bicycle/skateboard/rollerblading

Sport

Walking/running

Fighting

Up/down stairs

Driving/passenger

Working

Water activities

Drinking/eating

Other

Totals

Males (%)

30

20

24

17

9

(23.8)

(15.9)

(19)1.

(13.5)

(7.1)1.

5 (4)1.

7 (5.6)

4 (3.2)

10 (7.9)1

126

these latter activities were more equally divided

between the sexes or were too small to analyse.

No significant difference in frequency of trauma was

observed for different days of the week. However, there

were significantly more dental trauma incidents

reported in the months July through October compared

with the rest of the year (P<0.001). The largest number

of accidents (34.5 per cent) occurred between noon and

4pm (p<0.001). Most accidents occurred outdoors,

(65.5 per cent), (p<0.001), reflecting the patients

activities at the time of the accident. The time of the

injury tended to reflect the nature of the accident. For

example, 60 per cent of the accidents that resulted from

fights occurred in the hours between midnight and 4am

whilst 50 per cent of the bicycle accidents occurred in

the hours between 4pm and 8pm (after school hours).

Most accidents occurred at home (28.4 per cent) or on

the road/footpath or in the pool or at the beach (14.2

per cent each). Sportsgrounds were also a very common

location for injury amongst the male population (16.7

per cent) (Table 4).

Five of the seven patients who were either driving or

passengers in cars were wearing seatbelts at the time of

the accident. Only 53.6 per cent of the dental trauma

patients who were either riding a bike, skateboard or

rollerblades at the time of the accident were

wearing helmets and only 6 per cent of patients who

were injured whilst playing sport were wearing a

protective mouthguard. The types of sports involved in

these dental injuries included tennis, cricket, rugby

league and rugby union, AFL football, soccer and

basketball.

Females (%)

15

8

9

12

1

3

2

3

4

14

71

(21.1)

(11.3)

(12.7)

(16.9)

(1.4)

(4.2)

(2.8)

(4.2)

(5.6)

(19.7)

Total (%)

45

28

33

29

10

3

7

7

7

4

24

197

(22.8)

(14.2)

(16.8)

(14.7)

(5.1)1

(1.5)1

(3.6)1

(3.6)1

(3.6)1

(2)1

(12.2)

Of the 32 patients who were classified as working,

17 required time off work due to their injuries, while 45

of the 116 patients who were students required time off

school for their injuries. A further 13 per cent of injured

children required a family member to take time off

work to care for them. However, it was difficult to

establish whether the lost time from work and school

was a direct reflection of the dental and facial injuries

only, or whether it was due to other bodily injuries

sustained in the same incident.

Trauma patients most frequently injured their

maxillary central incisors in both primary and

secondary dentitions (72 per cent and 63.7 per cent

respectively), while maxillary lateral incisors were

affected in 16 per cent of patients (9.8 per cent in the

primary dentition and 17.8 per cent in the secondary

dentition) (Table 5).

The most common type of injury in both the primary

and secondary dentitions was uncomplicated enamel

and dentine fracture. Concussion and subluxation were

equally the second most common dental injuries in the

secondary dentition whilst subluxation was the next

most common injury in the primary dentition. There

were proportionally more injuries to the hard dental

tissue and pulp in the secondary dentition compared

with the primary dentition (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

This study provides an overview of the aetiology of

dental/oral trauma in a diverse south-east Queensland

population. Prospective studies are more advantageous

than their retrospective counterpart studies as they

Table 4. Location of accident causing injuries

Location of accident

Males (%)

Home

Road/footpath

Pool/surf

Sportsground

Other private home

School

Workplace

Public bar/nightclub

Shopping centre

Funpark/park

Other

Totals

30

17

16

21

13

8

7

4

2

2

5

125

144

(23.8)

(13.5)

(12.7)

(16.7)

(10.3)

(6.3)

(5.6)

(3.2)

(1.6)

(1.6)

(4)1.

Females (%)

26

11

12

4

3

5

1

2

4

1

69

(36.6)

(15.5)

(16.9)

(5.6)

(4.2)

(7)1.

(1.4)

(2.8)

(5.6)

(1.4)

Total (%)

56

28

28

25

16

13

8

6

6

2

7

195

(28.4)

(14.2)

(14.2)

(12.7)

(8.1)1

(6.6)1

(4.1)1

(3)1

(3)1

(1)1

(3.6)

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:2.

Table 5. Frequency of tooth specific injuries in primary and secondary dentitions

Injured tooth

Primary dentition

Secondary dentition

Total

59

8

7

7

1

82

179

50

23

16

6

4

2

1

281

238

58

30

23

7

4

2

1

363

Maxillary central incisors

Maxillary lateral incisors

Mandibular central incisors

Mandibular lateral incisors

Maxillary canines

Mandibular canines

Maxillary premolars

Mandibular premolars

Total

allow more accurate information to be gathered at the

time (or close to the time) of the accident occurring.

Retrospective (prevalence) studies will miss those cases

whose signs and/or symptoms have disappeared at the

time of the examination (months or possibly years after

the trauma occurred). However, it must be kept in

mind, that prospective studies may also miss some cases

if patients do not seek treatment for their injuries. Thus

the figures presented in either type of study could be

expected to be lower than the actual rates in the

community.

Given the age range of the patients studied, the

results provide one estimate of expected rates of dental

and oral trauma in the general population. The highest

frequency of trauma occurred in the 6-10 year old age

group and was in agreement with other studies.3,5,6,11

Playing and riding bicycles were the most frequently

associated activities, while in the 16-20 year old group

fighting and sport were the predominant activities.

Assaults or fights were also the second and third most

common cause of dental injury in studies by Davis and

Knott5 and Perez et al.12 respectively.

The predominance of injuries in males (1.8:1.0) was

similar to other Australian and overseas studies which

reported sex ratios between 1.4-2.2:1.0.1,2,5-8,13-16 Two

Australian studies by Martin et al.,3 and Liew and Daly4

established a higher male:female ratio of 2.6:1.0. These

studies examined patients attending after hours clinics

which resulted in a higher incidence for 18-23 year

olds. This age group may also reflect a greater number

of males participating in sports and fights in the

evenings and on weekends compared with females.

The majority of the injuries noted in our study

involved the maxillary central incisors for both the

primary and secondary dentitions, a finding consistent

with the literature on dental trauma. Compared with

other cross-sectional studies in which trauma has been

reported to affect a single tooth in the one individual,

this study found that there were approximately 2.4

injuries per patient. This may be due to the differences

in data collection among different studies. Injuries to all

teeth were recorded in this study compared with other

studies where only injuries to either anterior teeth, or

specifically, injuries to primary or permanent teeth were

recorded. This high number of injuries per patient has

also been reported by Martin et al.3 and Galea13 where

data were collected from casualty and emergency

departments at hospitals. This may once again suggest

that patients experiencing more severe injuries, or

injuries occurring after hours, attend hospitals rather

than public or private dental clinics.

The main difference between the primary and second

dentition observed in this study was the types of

injuries sustained. The majority of injuries to the

primary dentition were injuries to the periodontal

tissue, whilst for the secondary dentition, the majority

of injuries were to the hard dental tissue and pulp.

There were also proportionately more alveolar

Table 6. Types of dental injuries occurring in the primary and secondary dentitions

Primary dentition

Type of injury

Uncomplicated enamel fracture

Uncomplicated enamel and dentine fracture

Complicated crown fracture (pulp exposed)

Uncomplicated crown and root fracture

Complicated crown/root fracture (pulp exposed)

Root fracture

Concussion

Subluxation loosening not displaced

Extrusion

Lateral luxation

Intrusive luxation

Avulsion

Comminution alveolar socket

Fracture alveolar socket wall

Fracture alveolar process, socket involvement

Fracture alveolar process, no socket involvement

Mandible/maxilla fracture, socket involvement

Mandible/maxilla fracture, no socket involvement

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:2.

Secondary dentition

Male

Female

Male

Female

4

12

6

2

2

9

11

9

10

3

5

3

5

7

4

3

4

4

2

15

51

15

6

6

10

28

29

9

14

8

15

2

4

5

8

2

19

37

13

1

1

16

9

4

6

5

10

11

Total

41

105

41

7

8

13

57

52

26

30

20

32

2

11

5

19

3

145

fractures in the primary dentition compared with the

secondary dentition. It was also interesting to note that

all alveolar fractures occurred only in males for both

the primary and secondary dentitions. Some investigators

have indicated that the supporting structures in the

primary dentition are more resilient than those in the

secondary dentition, thereby favouring dislocations

rather than fractures of the hard dental tissue.17,18

Significantly more accidents occurred in and around

the home and on the road or footpath compared with

other locations. This was also the case in two separate

Australian studies by Stockwell1 and Davis and Knott.5

Galea13 and Onetto14 also found that most injuries

occurred around the home or school and on the street.

It was disturbing to find that only a minority of

patients who were injured whilst playing sport were

wearing a mouthguard and only half of those injured

whilst riding a bicycle, skateboard, or rollerblades were

wearing any protective head or mouth gear.

Mouthguards, particularly custom made mouthguards,

offer significant protection to the teeth and oral

structures and their use should be encouraged to

prevent injuries during sport.19

Time lost from work or school due to dental and oral

injuries is significant. Both groups were unable to carry

on with their normal day-to-day activities for an

average of approximately five days. It should be noted

that this figure may be an underestimate of time lost

since school and public holidays were not included in

time lost from work and school.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the present study provide an estimate

of the expected rates of dental and oral tissue injuries in

the general population in Queensland although it must

be accepted that the survey outcomes were affected by

the non-participation of some potential respondents

and by the need of some patients to seek out-of-hours

emergency treatment at hospitals and therefore remain

outside the scope of our sampling methodology. This

may indicate that the actual population rates are higher

than reflected by this study.

Some of the most significant causes of injury revealed

by the present study are due to incidents while playing

sport or riding bicycles, skateboards and rollerblades.

Only a small percentage of those injured in these

activities were wearing protection. All of these activities

are susceptible to preventive measures and given the

amount of time lost due to associated injuries, it seems

reasonable to suggest that there is still considerable

scope for the profession to educate the public more

widely of the potential dangers and complications of

dental and oral injuries.

AC K N OW L E D G M E N T S

This study was supported by the Motor Accident

Insurance Commission/Centre of National Research on

146

Disability and Rehabilitation Medicine and the

Australian Research Council.

REFERENCES

1. Stockwell AJ. Incidence of dental trauma in the Western

Australian School Dental Service. Community Dent Oral

Epidemiol 1988;16:294-298.

2. Burton J, Pryke L, Rob M, Lawson JS. Traumatized anterior

teeth amongst high school students in northern Sydney. Aust

Dent J 1985;30:346-348.

3. Martin IG, Daly CG, Liew VP. After-hours treatment of anterior

dental trauma in Newcastle and western Sydney: a four-year

study. Aust Dent J 1990;35:27-31.

4. Liew VP, Daly CG. Anterior dental trauma treated after-hours in

Newcastle, Australia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1986;

14:362-366.

5. Davis GT, Knott SC. Dental trauma in Australia. Aust Dent J

1984;29:217-221.

6. Oulis CJ, Berdouses ED. Dental injuries of permanent teeth

treated in private practice in Athens. Endod Dent Traumatol

1996;12:60-65.

7. Caliskan MK, Turkun M. Clinical investigation of traumatic

injuries of permanent incisors in Izmir, Turkey. Endod Dent

Traumatol 1995;11:210-213.

8. Hamilton FA, Hill FJ, Holloway PJ. An investigation of dentoalveolar trauma and its treatment in an adolescent population.

Part 1: The prevalence and incidence of injuries and the extent

and adequacy of treatment received. Br Dent J 1997;182:91-95.

9. Andreasen JO. Traumatic injuries of the teeth. 2nd edn.

Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1981.

10. Dawson-Saunders B, Trapp RG. Basic and clinical biostatistics.

2nd edn. Connecticut: Appleton and Lange, 1994.

11. Zerman N, Cavalleri G. Traumatic injuries to permanent

incisors. Endod Dent Traumatol 1993;9:61-64.

12. Perez R, Berkowitz R, McIlveen L, Forrester D. Dental trauma in

children: a survey. Endod Dent Traumatol 1991;7:212-213.

13. Galea H. An investigation of dental injuries treated in an acute

care general hospital. J Am Dent Assoc 1984;109:434-438.

14. Onetto JE, Flores MT, Garbarino ML. Dental trauma in children

and adolescents in Valparaiso, Chile. Endod Dent Traumatol

1994;10:223-227.

15. Kaba AD, Marechaux SC. A fourteen-year follow-up study of

traumatic injuries to the permanent dentition. ASDC J Dent

Child 1989;56:417-425.

16. Forsberg CM, Tedestam G. Traumatic injuries to teeth in Swedish

children living in an urban area. Swed Dent J 1990;14:115-122.

17. Andreasen JO. Etiology and pathogenesis of traumatic dental

injuries: A clinical study of 1,298 cases. Scand J Dent Res

1970;78:329-342.

18. Ravn JJ. Dental injuries in Copenhagen schoolchildren, school

years 1967-1972. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1974;2:231245.

19. Welbury RR, Murray JJ. Prevention of trauma to teeth. Dent

Update 1990;3:117-121.

Address for correspondence/reprints:

Professor Terry Freer

School of Dentistry

The University of Queensland

200 Turbot Street

Brisbane, Queensland 4000

Email: t.freer@mailbox.uq.edu.au

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:2.

Вам также может понравиться

- Kriteria Skoring (1-5) : Prevalence Seriousness Manageability Community ConcernДокумент1 страницаKriteria Skoring (1-5) : Prevalence Seriousness Manageability Community ConcernMaria AprilianaОценок пока нет

- Jadwal IndivioduДокумент14 страницJadwal IndivioduMaria AprilianaОценок пока нет

- Jadwal IndivioduДокумент14 страницJadwal IndivioduMaria AprilianaОценок пока нет

- Chek List Pokja KlinisДокумент72 страницыChek List Pokja KlinisbuntarОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- 1219201571137027Документ5 страниц1219201571137027Nishant SinghОценок пока нет

- Jao Vs Court of Appeals G.R. No. 128314 May 29, 2002Документ3 страницыJao Vs Court of Appeals G.R. No. 128314 May 29, 2002Ma Gabriellen Quijada-TabuñagОценок пока нет

- Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche - Meditation On EmptinessДокумент206 страницKhenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche - Meditation On Emptinessdorje@blueyonder.co.uk100% (1)

- 11 PJBUMI Digital Data Specialist DR NOOR AZLIZAДокумент7 страниц11 PJBUMI Digital Data Specialist DR NOOR AZLIZAApexs GroupОценок пока нет

- Nota 4to Parcial AДокумент8 страницNota 4to Parcial AJenni Andrino VeОценок пока нет

- Sokkia GRX3Документ4 страницыSokkia GRX3Muhammad Afran TitoОценок пока нет

- Persian NamesДокумент27 страницPersian NamescekrikОценок пока нет

- UNIT VI. Gunpowder and ExplosivesДокумент6 страницUNIT VI. Gunpowder and ExplosivesMariz Althea Jem BrionesОценок пока нет

- Crochet World October 2011Документ68 страницCrochet World October 2011Lydia Lakatos100% (15)

- Multiple ChoiceДокумент3 страницыMultiple ChoiceEfrelyn CasumpangОценок пока нет

- Agreement of PurchaseДокумент8 страницAgreement of PurchaseAdv. Govind S. TehareОценок пока нет

- Nielsen Esports Playbook For Brands 2019Документ28 страницNielsen Esports Playbook For Brands 2019Jean-Louis ManzonОценок пока нет

- ISO 9001 QuizДокумент4 страницыISO 9001 QuizGVS Rao0% (1)

- Grill Restaurant Business Plan TemplateДокумент11 страницGrill Restaurant Business Plan TemplateSemira SimonОценок пока нет

- 5 L&D Challenges in 2024Документ7 страниц5 L&D Challenges in 2024vishuОценок пока нет

- Proyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusДокумент18 страницProyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusAllen Marcelo Ballesteros LópezОценок пока нет

- 008 Supply and Delivery of Grocery ItemsДокумент6 страниц008 Supply and Delivery of Grocery Itemsaldrin pabilonaОценок пока нет

- The Confederation or Fraternity of Initiates (1941)Документ82 страницыThe Confederation or Fraternity of Initiates (1941)Clymer777100% (1)

- Profix SS: Product InformationДокумент4 страницыProfix SS: Product InformationRiyanОценок пока нет

- 2.1BSA-CY2 - REVERAL, ANGELA R. - EXERCISE#1 - Management ScienceДокумент3 страницы2.1BSA-CY2 - REVERAL, ANGELA R. - EXERCISE#1 - Management ScienceAngela Ricaplaza ReveralОценок пока нет

- Unit 4: Alternatives To ImprisonmentДокумент8 страницUnit 4: Alternatives To ImprisonmentSAI DEEP GADAОценок пока нет

- Sociology of Arts & HumanitiesДокумент3 страницыSociology of Arts & Humanitiesgayle gallazaОценок пока нет

- Cyber Ethics IssuesДокумент8 страницCyber Ethics IssuesThanmiso LongzaОценок пока нет

- Faculty of Computer Science and Information TechnologyДокумент4 страницыFaculty of Computer Science and Information TechnologyNurafiqah Sherly Binti ZainiОценок пока нет

- PH Scale: Rules of PH ValueДокумент6 страницPH Scale: Rules of PH Valuemadhurirathi111Оценок пока нет

- High-Performance Cutting and Grinding Technology For CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic)Документ7 страницHigh-Performance Cutting and Grinding Technology For CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic)Dongxi LvОценок пока нет

- Ingrid Gross ResumeДокумент3 страницыIngrid Gross Resumeapi-438486704Оценок пока нет

- SyerynДокумент2 страницыSyerynHzlannОценок пока нет

- How To Format Your Business ProposalДокумент2 страницыHow To Format Your Business Proposalwilly sergeОценок пока нет

- Exeter: Durance-Class Tramp Freighter Medium Transport Average, Turn 2 Signal Basic Pulse BlueДокумент3 страницыExeter: Durance-Class Tramp Freighter Medium Transport Average, Turn 2 Signal Basic Pulse BlueMike MitchellОценок пока нет