Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Introduction What Future For Industrial Relations

Загружено:

AdaLydiaRodriguezОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Introduction What Future For Industrial Relations

Загружено:

AdaLydiaRodriguezАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

International Labour Review, Vol. 154 (2015), No.

Introduction:

What future for industrial relations?

Susan HAYTER*

Abstract.In her introductory paper, the coordinator of this Special Issue puts

the selection of subsequent contributions into context. Traditional industrial relations institutions, born of labour laws premise of unbalanced power relations

between the worker and the employer, are being undermined by unprecedented

global changes in patterns of work and forms of employment. This trend, compounded by the emergence of alternative forms of worker representation, poses a

major challenge not only to conventional tradeunionism but also to policy and to

industrial relations scholarship. This Special Issue is intended as a contribution to

the ensuing, ongoing debate about the direction of future change.

ndustrial relations as a field of scholarship and policy is over a century old,

dating back to the classic study by Beatrice and Sydney Webb (1897) on

the regulation of employment in Britain and the writings of John R. Commons

(1905) on the causes of, and solutions to, the labor problem in the United

States. These early theories on trade unions provided valuable insights on the

device of the common rule. By bargaining collectively, trade unions could

balance the (otherwise unequal) bargaining power in employment relations

and negotiate standard wage rates and hours of work. This placed a floor under

wages and working conditions and protected workers from some of the adverse effects of competition. Industry-wide collective bargaining was seen as

accomplishing a progressive compromise with stabilizing effects for the industry concerned and for the economy (Kaufman, 2003).

Industrial relations developed into a broad field of study, encompassing work and employment relations and the actors and processes that govern

them. Particular attention has been given to those involving collective organization and action. Central themes in the industrial relations literature include

trade unions, employers organizations, collective bargaining, strikes, collective labour law and policy concertation leading to social pacts. Industrial relations research is also increasingly concerned with assessing the outcomes of

* ILO, email: hayter@ilo.org.

Responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles rests solely with their authors, and

publication does not constitute an endorsement by the ILO.

Copyright International Labour Organization 2015

Journal compilation International Labour Organization 2015

International Labour Review

processes on wages (and their distribution), working time arrangements, turnover and other labour outcomes, as well as on the performance of enterprises

and the economy.1 While at times criticized for its weak theoretical underpinnings (Kaufman, 2004), contemporary industrial relations scholarship continues to make theoretical contributions to this and related fields on new

social movements (Kelly, 1998), varieties of capitalism (Hall and Soskice, 2001)

and institutional change (Thelen, 2009).

Industrial relations is premised on the understanding that enterprises

and workers have different and even conflicting goals and interests. Labour

disputes, strikes, public protests and other forms of collective action are the

clearest manifestations of this conflict, but high labour turnover and absenteeism, low morale and general inefficiency can be symptomatic too. Industrial relations provides an analytical framework with which to make sense of

this domain of contestation. As a policy-oriented field of study it also engages

scholarship with debates in workplaces, in communities and at the policy

level on effective strategies for improving the conditions of working people.

Significant changes have occurred in the world of work, calling into question the effectiveness of the industrial relations toolkit of institutional fixes.

Inequality and insecurity are the most significant labour problems of our

era. According to the ILOs (2015) estimates, 201 million workers were unemployed in 2014. Rapid advances in technology have changed the way in

which work is organized. Working arrangements are more diverse than in the

past. Zero-hour contracts, one of the newer contractual forms in which the

employer decides at will on the number of hours to be worked, place workers

in positions of extreme insecurity with no minimum pay guarantees.2 Trade

unions a critical subject for industrial relations have seen their membership and influence wane in many parts of the world. Shifts towards shareholder- or market-oriented corporate governance and the emergence of global

production networks have further weakened the bargaining power of labour.

Meanwhile, in many developing countries, most work continues to be carried

out in the informal economy, outside of the purview of formal industrial relations institutions.

The challenge is to make sense of this changing landscape and what it

means for the actors and institutions aspiring to deliver decent wages and

working conditions. Firmly rooted in a tradition of critical social science and

with its rich multidisciplinary approach, industrial relations is at a distinct advantage when it comes to studying these changes and their implications for

actors, institutions and outcomes (Clarke et al., 2011). It is in this context that

we ask: What future for industrial relations? Are its institutions outmoded?

Merely a relic of a golden age to be written up in a history project? Have new

1

For an example of the richness and broad reach of current industrial relations scholarship,

see Blyton et al. (2008).

2

For examples, see http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/dec/04/zero-hourscontracts-teaching-job-insecurity [accessed 19 February 2015].

What future for industrial relations?

modes of communication, organization and mobilization eclipsed traditional

membership-based organizations? Is there a fundamental mismatch between

industrial relations institutions and our current labour problems? Have work

and labour changed to such a degree that the institutions created to give workers a voice and representation are now obsolete?

The papers in this Special Issue emerged from a plenary debate that took

place during the ILOs Regulating for Decent Work Conference in 2013. The

contributing scholars have decades of cumulative wisdom among them and

come from different parts of the world. They share a common endeavour: the

study of work, employment relations, and the organizations and processes that

deliver labour protection and elicit the participation of workers in determining the quality of their working lives. They provide a jarring account of the

present and a considered reflection on the future of work and possibilities for

institutional renewal.

Richard Hyman makes the opening statement by setting out three alternative futures: from bad to worse, envisaging the continuing erosion of national industrial relations systems; elite reform, envisaging a shift in public

policy; and a new counter-movement, in which new solidarities between collective actors rebalance the economy and the status of work within it. Janice

Fine then provides a ray of hope, illuminating Hymans latter scenario with her

description of emerging micro-industrial relations regimes involving new solidarities between trade unions and worker centres. Eddie Webster, as well as

Ratna Sen and Chang-Hee Lee, shed additional light on this possible future.

Webster argues that the new initiatives, organizational forms and sources of

power at the periphery of traditional labour markets have planted the seeds

for the flowering of a new global labour studies. Reflecting on the development of industrial relations in South Africa, he questions the possibility of

institutionalized industrial relations in a world with such high unemployment

and wide inequality. Ratna Sen and Chang-Hee Lee also reflect upon the institutionalization of industrial relations and the emergence of alternative countermovements in large emerging economies, such as India and China.

Maarten Keune examines the battle of ideas and the paradoxes that

have driven the overall trajectory of industrial relations in Europe from bad

to worse. He does not see this as an irreversible trajectory and identifies

signs of a new counter-movement. In his concluding contribution, Gerhard

Bosch envisages a future that lies somewhere between elite reform and a

new counter-movement, driven by institutional renewal and innovation. In his

view, efforts to combat inequality will require a strengthening of protective and

participatory standards: state intervention in wage determination (i.e. a statutory minimum wage) and collective bargaining taking place in the shadow of

the law. He offers a real-life example of this transition from autonomous to

hybrid in Germanys collective bargaining system where the policy intention

is to use the minimum wage as a platform for strengthening collective bargaining. It is the combination of protective and participative rights that appears to

lead to better outcomes.

International Labour Review

Together, these papers are intended to serve as a reflection of developments in work and employment relations, providing insights that are at times

uncomfortable but nevertheless illuminate some of the possibilities for institutional renewal.

References

Blyton, Paul; Bacon, Nicolas; Fiorito, Jack; Heery, Edmund (eds). 2008. The SAGE

Handbook of Industrial Relations. London, Sage.

Clarke, Linda; Donnelly, Eddy; Hyman, Richard; Kelly, John; McKay, Sonia; Moore, Sian.

2011. Whats the point of industrial relations?, in The International Journal of

Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 239253.

Commons, John R. (ed.). 1905. Trade unionism and labor problems. Boston, MA, Ginn

and Company.

Hall, Peter A.; Soskice, David (eds). 2001. Varieties of capitalism: The institutional

foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

ILO. 2015. World Employment and Social Outlook Trends 2015. Geneva.

Kaufman, Bruce E. 2004. The global evolution of industrial relations: Events, ideas and the

IIRA. Geneva, ILO.

. 2003. John R. Commons and the Wisconsin School on industrial relations strategy

and policy, in Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 57, No. 1 (Oct.), pp. 330.

Kelly, John. 1998. Rethinking industrial relations: Mobilization, collectivism and long waves.

London, Routledge.

Thelen, Kathleen. 2009. Institutional change in advanced political economies, in British

Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 471498.

Webb, Sydney; Webb, Beatrice. 1897. Industrial democracy. London, Longmans, Green and

Co.

Вам также может понравиться

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Kasapian NG Malayang Manggagawa Sa Coca-Cola vs. CA, 487 SCRA 487Документ10 страницKasapian NG Malayang Manggagawa Sa Coca-Cola vs. CA, 487 SCRA 487JoeyBoyCruzОценок пока нет

- Mabeza v. NLRC, April 18, 1997Документ12 страницMabeza v. NLRC, April 18, 1997BREL GOSIMATОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Leadership Skills: BY Imitini, Elo Merit (Project Engineer)Документ16 страницLeadership Skills: BY Imitini, Elo Merit (Project Engineer)Merit EloОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

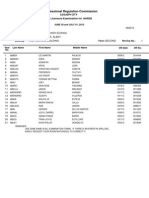

- June - July 2012 Nurse Licensure Examination Room Assignment (Legazpi City) CompleteДокумент112 страницJune - July 2012 Nurse Licensure Examination Room Assignment (Legazpi City) CompletejamieboyRNОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- AIS Romney 2006 Slides 13 The HR CycleДокумент87 страницAIS Romney 2006 Slides 13 The HR Cyclesharingnotes123Оценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Case Study (Airsoft Company)Документ3 страницыA Case Study (Airsoft Company)diana jane torcuatoОценок пока нет

- Interviewing WP DdiДокумент11 страницInterviewing WP DdiRamona GogoasaОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Aided Schools of PunjabДокумент4 страницыAided Schools of PunjabSandy DograОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- (Promotion Policy of APDCL) by Debasish Choudhury: RecommendationДокумент1 страница(Promotion Policy of APDCL) by Debasish Choudhury: RecommendationDebasish ChoudhuryОценок пока нет

- Human Resource Management - Theory and Practice 5th Edition PDFДокумент673 страницыHuman Resource Management - Theory and Practice 5th Edition PDFZee Zioa83% (18)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- Unemployment Insurance Application: Filing InstructionsДокумент12 страницUnemployment Insurance Application: Filing InstructionsSylvester sampsonОценок пока нет

- Long Quiz 3Документ12 страницLong Quiz 3mary annОценок пока нет

- Information Release Form / Consent FormДокумент1 страницаInformation Release Form / Consent FormandrechuaОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Human dignity and workДокумент2 страницыHuman dignity and workKê MilanОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- RA CHEMENG CEBU May2019 PDFДокумент8 страницRA CHEMENG CEBU May2019 PDFPhilBoardResultsОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Melissa Siemers ResumeДокумент2 страницыMelissa Siemers Resumeapi-354609638Оценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Summer Internship Report On "Trade Unions A Study of SelecteДокумент38 страницSummer Internship Report On "Trade Unions A Study of Selecteavantikarana864Оценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- 13 Salary 1Документ1 страница13 Salary 1Benj Jamieson Jocson DuagОценок пока нет

- Civility in NursingДокумент7 страницCivility in Nursingshawnee11Оценок пока нет

- Chapter Two ThreeДокумент30 страницChapter Two ThreeSandra NwabuokuОценок пока нет

- PRODUCT DESCRIPTIONS - Systech PayrollДокумент6 страницPRODUCT DESCRIPTIONS - Systech PayrollMahamudul HasanОценок пока нет

- Sample Catherine Confectionary Write UpДокумент11 страницSample Catherine Confectionary Write UpCourtney Tucker100% (1)

- CTC Break-Up PDFДокумент5 страницCTC Break-Up PDFJatinder SadhanaОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- A Method For Ergonomics Analysis: EAWSДокумент24 страницыA Method For Ergonomics Analysis: EAWSpkj009Оценок пока нет

- Salary Sep 2019 PDFДокумент1 страницаSalary Sep 2019 PDFAnonymous eHnCyk7DYОценок пока нет

- Cover Letter For Plant NurseryДокумент5 страницCover Letter For Plant Nurserygt690fw6100% (1)

- Entrepreneurship Guide for SHS StudentsДокумент49 страницEntrepreneurship Guide for SHS StudentsNicolePasilan100% (1)

- Simply Management - The Book - 02-29-12 PDFДокумент207 страницSimply Management - The Book - 02-29-12 PDFCaio GiarettaОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- EltpcaДокумент12 страницEltpcaSubhojit MandalОценок пока нет

- OSHA Safety ManualДокумент265 страницOSHA Safety Manualkanji63Оценок пока нет