Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

7 Full

Загружено:

rifqi235Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

7 Full

Загружено:

rifqi235Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

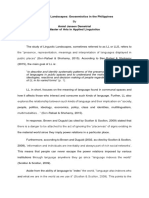

Sunday 1914, Open House at the residence of Professor Ignaz Jastrow,

24 Nussbaumallee, in Berlins West End. Courtesy of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander

(Vancouver, Canada). Jastrow is between Georg and Gertrud Simmel. On the back of the

photo, Mrs Oberlanders mother, Beate Hahn (nee Jastrow), remarks on the characteristic

gestures (typische Bewegungen) that Simmel made when speaking (see Note 1 of the

Introduction).

Article

Introduction: Georg

Simmels Sociological

Metaphysics: Money,

Sociality, and Precarious

Life

Theory, Culture & Society

29(7/8) 725

! The Author(s) 2012

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0263276412459087

tcs.sagepub.com

Austin Harrington

University of Leeds, UK

Thomas M. Kemple

University of British Columbia, Canada

Abstract

The articles brought together in this double-length section of the Annual Review of

Theory, Culture & Society focus on two intertwined strands of the thought of Georg

Simmel, both of them neglected until recent years. A first bears on what might be

called Simmels metaphysics of the social, or what he himself once called sociological

metaphysics. A second strand centres on the renewed contemporary relevance of

Simmels ideas about money economies and their relation to precarious individual

life-situations in an age of global economic turbulence. Current sensibilities in the

wake of global economic crisis and the demise of some of the more euphoric sociologies of globalization of the last two decades provide a timely setting for a reappraisal of Simmels thinking. With the completion in 2012 of the Suhrkamp edition of

Simmels collected works, Simmels themes need to be explored more deeply, including particularly his thinking about lived experience, transcendence, death, fragmentary worlds of value, and allegorical representation. This issue of the journal

showcases some of the latest scholarly work and foregrounds several pivotal primary

pieces unavailable in English until now.

Keywords

allegory, life, metaphysics, money, Simmel, sociality, vitalism

Corresponding author:

Austin Harrington, University of Leeds, Woodhouse Lane, Leeds LS29JT, UK

Email: a.harrington@leeds.ac.uk

http://www.sagepub.net/tcs/

Theory, Culture & Society 29(7/8)

Since the 1980s, attention has turned increasingly toward Georg

Simmels ideas about culture, aesthetics, urbanism and modernity, building on earlier engagements in the 1960s and 1970s with his theories of

sociation, interaction and individuation. Until recently, however,

Simmels extensive writings on more philosophical or trans-sociological

questions have tended to be left in the dark. At the forefront of these

hitherto neglected dimensions of Simmels corpus are questions about

Life and its meaning in relation to basic structures of existence, value

and death.

Current sensibilities in the wake of global economic crisis and the

demise of some of the more euphoric sociologies of globalization of

the last two decades provide a timely setting for a reappraisal of

Simmels important thinking about how money economies, with their

logics of ctionalization, virtualization, and aestheticization, become displaced from lived realities. Long before ideas of mobility, uidity, ows,

scapes, liquidity and space-time contraction became fashionable in the

1990s as descriptors of globalizing processes, Simmels multifaceted

thinking about exchange and reciprocity and forms of sociation had

already anticipated these themes. But in contrast to much contemporary

globalization commentary (at least until recently), Simmels ideas also

help us understand the signicance of the fragility and fallibility of global

systems for meaningful life-projects and stable gurations of action.

More than 90 years since his death, large chunks of Simmels work still

remain largely unexplored today, as a glance at the 24 volume

Gesamtausgabe quickly reveals (see Otthein Rammstedts overview of

the recently completed Collected Works in this issue). Signicantly,

this neglect includes those parts of Simmels corpus that reach beyond

sociological analysis in any conventional sense, but that can be understood to inform and underpin contemporary social theoretical and cultural inquiry. Especially overlooked have been Simmels wide-ranging

writings in general philosophical anthropology and philosophy of life

(Lebensphilosophie), bearing on themes of death, redemption and selfrealization, on spheres or worlds of value (such as art, religion, science),

on phenomena of totality and fragmentation, immanence and transcendence. No less so have been a great number of vital essayistic pieces that

demonstrate Simmels uniquely gurative, allegorical, and aphoristic

style of writing and thinking in which Simmel experiments with a variety

of literary genres which both comment on and perform social realities

that often seem to elude comprehension in more standard analytical

formats.

In this double issue of Theory, Culture & Society we give special attention to the rich body of philosophical and metaphysical themes that

inform Simmels last great publication, his recently translated

Lebensanschauung or View of Life, a work that stands as the authors

Harrington and Kemple

last philosophical reckoning with life in the face of his own looming

death in September 1918 and that until very recently has somehow managed to elude the serious scholarly engagement it deserves. At the same

time, we also emphasize the increasing relevance of Simmels two classic

works, his Philosophy of Money of 1900/1907 and Sociology of 1908 the

latter also recently translated in English in full for the rst time, more

than a century since its release, and despite periodic waves of partial

translations beginning in the late 19th century. The new translation of

Sociology brings home to English readers how many familiar pieces

appear here as distinct contributions to a larger thesis, or as excurses

marked o from the main text by subheadings and smaller print, and

makes more evident the volumes project of mapping an emerging new

eld of scientic investigation by focusing more on the forms and processes of social life than on its empirical contents or experiential substance (Sto). Together with The Philosophy of Money, the recent

availability of Simmels Sociology and View of Life in English now facilitates the task of thinking about how the dual sociological and philosophical polarities of Simmels work relate to one another across the

continuous trajectory of his intellectual biography. English-language

readers of Simmel can now see more clearly how urgent existential questions of life and death wait in the wings of Simmels earlier more scientic

and disciplinary concerns, and conversely how life ultimately emerges as

the thematic capstone of his enduring career as a sociologist.

In all of these respects, a special concern of this special section is to

pay tribute to the work of the late David Frisby (19442010), who did so

much to rescue Simmels work from the threat of oblivion and to protect

him from the risk of being remembered only as the most important and

interesting transitional gure in the history of philosophy, as Georg

Lukacs notoriously judged him (see Thomas Kemples introduction to

the special commemorative e-issue of David Frisbys writings for TCS

(Kemple, 2010) and Chronology of Simmels Writings in English in this

issue). Following in the footsteps of Frisbys work, the contributors to

this issue draw from a broad range of Simmels writings in philosophy,

social psychology, cultural geography, ethics, and modernist aesthetics.

We highlight two key emerging strands from the spread of the latest

scholarly engagement with Simmels work. A rst bears on what might

be called Simmels metaphysics of the social, or what he himself once

called sociological metaphysics. This revolves around such diverse

motifs of his thinking as lived experience, transcendence, fragmentary

worlds of value, and allegorical representation. A second strand centres

on the rich and renewed contemporary relevance of Simmels ideas about

money economies and their relation to precarious individual life-situations in an age of global economic turbulence.

10

Theory, Culture & Society 29(7/8)

Sociological Metaphysics

In a prominent passage from the closing pages of Sociology, Simmel

deploys the phrase sociological metaphysics to describe what we take

to be a mode or style of reection on trans- or meta-sociological phenomena. In the course of discussing the consequences of philosophical

speculation about the unity of society as a totality of the unique qualities

of each and every individual, and after commenting sociologically on the

intensication of individuality with the extension of social groups, he

ventures a speculative statement which he acknowledges is hard to demonstrate scientically, but which is nevertheless a legitimate and valid

problem of sociological metaphysics:

The more incomparable an individual is, that is, the more someone

stands in the order of the whole in a position reserved for that

person alone, llable only by that persons being, action, and fate,

the more is the whole to be comprehended as a unity, as a metaphysical organism, in which every soul is a member that can be

exchanged for no other but that nonetheless takes all other souls

and their interaction with one another as a presupposition of that

individuals own life. (Simmel, 2009 [1908]: 660; 1992 [1908]: 8423;

translation modied)

The idea of the equality of all as a unity of the greatest possible uniqueness of individuals has its roots, he goes on to say, in the Christian

doctrine of the immortal and innitely valuable soul.

Although sociological metaphysics is not a phrase Simmel deploys

frequently or with any specic technical intention, we use it here to

denote the striking organizing conuence in his work of sociological

investigation and philosophical reection on ultimate questions of existence. The conjunction of sociology and metaphysics entails both a disciplinary duality of empirical social science and speculative philosophy in

Simmels work, as well as a corresponding duality of social structure and

interaction on the one hand and human and non-human existence on the

other. It is this duality that explains how, while Simmels late work may

appear to leave sociology behind in order to retreat into purely philosophical, metaphysical, and aesthetic matters of contemplation of higher

spiritual values, his reections continue to turn around the themes of

social exchange which had been stressed in his early great sociological

works on money, social relations, interaction, and dierentiation.

In this sense of the intersection of two broadly polar dimensions of

inquiry, we understand sociological metaphysics as an idiom of thinking

in Simmels work encompassing core ideas and basic problems central to

the modernist project of critical reexive knowledge about the social

conditions of human existence. It names rst of all an insistence that

Harrington and Kemple

11

the traditional philosophical eld of metaphysics has a sociology, that is,

a relative and conditional position within denite historical contexts of

social relations and institutions. But second, it also denotes the idea that

compelling grounds exist for probing the liminal area at the intersection

of experiences that are open to denite empirical scientic observation

and to other dimensions of reality that can only be disclosed by other

means (see Kemple, 2007). Such a view rejects the positivist precept that

rational discourse cannot meaningfully and coherently transgress the

limits and boundaries of observable experience, and that talk of such

abstract ideas as beauty, freedom, salvation, or God must therefore be

removed from the competences of scientic writing and thinking and

surrendered to the purview of artists, poets and religious visionaries.

Sociological metaphysics in this sense remains continuous with the various uses that have been made of the terms philosophical anthropology

and philosophy of culture in German thought of the last eight or nine

decades, many of them substantially indebted to Simmels legacy

(Fischer, 2008).

To be sure, the specic language of philosophy that drives Simmels

writings from the rst two decades of the last century is no longer one we

can take for granted today in an age shaped by the linguistic turn and

by broadly postmodern approaches to cultural inquiry and by the rise

of the new cognitive and behavioural sciences of the last 40 years or so

(cf. Habermas, 1994). Undoubtedly, some work of conceptual translation

and reconstruction is required today a near-century after Simmels death.

But to think of metaphysics as simply an obsolescent paradigm of

thought today would be an unnecessary conclusion. Simmels and

other early 20th-century European thinkers existential questions

remain impossible to ignore today, even if the tropes mobilized to resolve

them in their time can on occasion seem perplexing or alien to us.

A number of texts in this issue of Theory, Culture & Society address

this thematic in Simmels work. We begin with some comments on a

series of essays by Simmel himself that have been translated into

English here for the rst time. A rst set of writings comprises the gurative, allegorical, and aphoristic pieces he contributed to the avantgarde journal Jugend from 1897 to 1907 (see the selections translated in

this special section), which also happens to be the decade when he was

writing and revising his monumental Philosophy of Money and assembling the components of Sociology. In contrast to his well-crafted books,

systematic treatises, and scholarly essays which advance key theoretical

arguments while portraying a repertoire of standard social types the

stranger, the city-dweller, the prostitute, the pauper, the miser, and so on

these pieces try out dierent, often ironic registers of voice. In the brief

epigrammatic sketches he published in the journal under the title

Momentbilder sub specie aeternitatis (literally, Snapshots under the

aspect of eternity), for instance, issues examined in the longer more

12

Theory, Culture & Society 29(7/8)

serious and systematic works are dealt with more playfully and even

comically. Judging from the title he gave to his series, Simmel is oering

a satirical spin on Spinozas wish to view things purely according to their

inner necessity and signicance, released from the contingency of the

here and now and dissolved from the relationship between before and

after, as if to provide positive content to the conception of absolute,

unied being where Spinoza could not, as Simmel suggests elsewhere

(Simmel, 1992 [1895]: 967; 2010: 11).

Although these literary stills of everyday scenes and ordinary encounters were produced in the early days of popular photography, they were

not accompanied by any actual snapshots, but rather by stylized designs

and graphic drawings characteristic of the Jugendstil movement which

celebrated individual creativity against the technological reproducibility

of art forms (Frisby, 1981: 101; Rammstedt, 1991; see the examples

reproduced in this issue and in TCS 8(3) 1991). Nevertheless, we might

consider for a moment the photographic snapshot (Momentbild) reproduced here of Simmel with his wife and friends at a Sunday garden party

in Berlins Westend in the summer of 1914, presumably taken just before

the outbreak of the rst World War and around the time Simmel was

Figure 1. Simmel, 1914, Open House in the garden of Professor Ignaz Jastrow,

24 Nussbaumallee, in Berlins West End. Courtesy of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander

(Vancouver, Canada).1

Harrington and Kemple

13

making the transition to his rst permanent position at the University of

Strasbourg.

As many of his students and acquaintances remember, Simmel had a

characteristic way of moving his hands and twisting his body as he spoke,

as if gesturing to grasp a moment of creative thought in the course of

expressing his own turn toward an idea (die Wendung zur Idee), as he

would later title a chapter from The View of Life (see also Stewart, 1999).

Viewed sub specie aeternitatis, or at least from the vantage point of the

personal fates, historical transformations, and political upheavals in the

lives of the people depicted here in the years that would immediately

follow, this image might suggest to us that not only on the lecture

podium or in the published work but also in private, improvised

moments of sociable conversation Simmel was grappling with those

metaphysical and sociological problems which can rst be glimpsed in

an instant and in statu nascendi. One could imagine the conversations

that Simmel reports overhearing in the comical Snapshots called

Money Alone Doesnt Bring Happiness, Relativity and La Duse,

or even the internal dialogue which frames the ironical Beyond

Beauty (all published in Jugend), to have emerged from just such intimate scenes of friendship and sociability.

Judging from his private correspondence and his writings in Jugend, by

the early years of the new century Simmel appears to have been ready to

withdraw from sociology altogether. As recent commentators have noted

(Tyrell, 2007; Tyrell et al., 2011), one motivation for Simmel in completing the Sociology volume may have been to settle accounts with one

aspect of his interests and professional ambitions in order to turn unencumbered to another to the trans-social validity-claims of art, philosophy and religious thought. It is notable in this regard that neither art

nor religion occupy any thematically central position in Sociology,

and it may be that around 1905 Simmel began to view art and religion

not only as social forms of relationship and interaction as

Vergesellschaftungsformen or soziale Beziehungsformen but also as

forms of consciousness sui generis, as quasi-apriori dimensions of

mental life tout court. Life, consciousness and mind in this sense

seem to be beckoning in Simmels thinking from this point onward as

higher limit-situations for which social science can provide only partial

illumination (Harrington, 2011; Krech, 1998).

This train of thought can be seen in a late essay of Simmels from 1916

on the theme of The Fragmentary Character of Life (translated in this

issue), a preliminary study for what would later become the second chapter of The View of Life. Here Simmel conveys a vision of conict between

multiple worlds of value and meaning such as art, religion, and science,

including implicitly social science. Life, Simmel arms, is embroiled

not only in the world but also in dierent perspectival worlds, each

with dierent ultimate claims to authority but whose conictual relations

14

Theory, Culture & Society 29(7/8)

to one another create eects of fragmentation for life. Yet life, Simmel

also says, evinces a practical capacity for mediation between fragmented

worlds, for insofar as these worlds cannot themselves exist other than as

objectivations of the ow of lifes creative energies, they presuppose that

life has a wholeness of which they are but parts. Life is thus at one and

the same time something fragmentary and whole, both articulated into

multiple discrete frames of ultimate relevance and nevertheless seamlessly

owing forward in a process of creative self-reconstitution (Harrington,

2012).

It is this conception of simultaneous fragmentation and ongoing reelaboration of life that Simmel explicates more fully in The View of Life

of 1918, available now in full in English with an appendix of aphorisms

and brilliant fragmentary sketches of thoughts from Simmels diaries

(Simmel, 2010 [1918]). Concluding with two engrossing chapters on

death and its meaning for individual life and individual ethical styles of

life (to which we turn shortly), Simmel begins here with a meditation on

life as a work of intellectual and emotional self-overcoming or transcendence of limits. Echoing Nietzschean musings about virtues of personal philosophical asceticism, he writes of life nding more-life only

through more-than-life, through limits to itself, through form and

objectivity as challenges to subjective will (Simmel, 2010 [1918]: 13).

Transcendence in this sense describes a way in which any Beyond or

transcendent condition, such as the religious or aesthetic, is not a place or

space or meta-physical domain of some kind but always only an inection of lifes immanent ow and diversity through time, space, and history, and across natures, cultures, and their associations (see

Kantorowicz, 1959 [1923]). Absolute ideas or limit-experiences on this

understanding have potentially coherent and important meanings for life

but only from a starting-point of this-worldly relativity. Absolutes absolve or break o from life and constitute their own independent fragmented worlds; but they also continuously dis-solve back again into

lifes ongoing ux and variety of cultural and historical forms.

As with his essay on The Fragmentary Character of Life, Simmels

View of Life resonates in numerous ways with some central concerns of

20th-century thinking about epistemological and axiological pluralism

and perspectivism from, say, William Jamess pluriverse or Alfred

Schutzs multiple realities (Schutz, 1966) to books such as Cornelius

Castoriadiss modernist World in Fragments (1997) or Zygmunt

Baumans postmodern Life in Fragments (Bauman, 1993) and the last

published work of Gilles Deleuze (1997, 2001). His arguments anticipate

more recent attempts to revive metaphysics in philosophy and sociology,

not all of which acknowledge Simmel as a precursor (Latour, 2005;

Harman, 2005; an exception is Lash, 2010: 313). As for Deleuze,

rather than posit some ancient scholarly doctrine about what exists

beyond the plane of the physical world, or promote popular ideas

Harrington and Kemple

15

about the mystical basis of reality, metaphysics for Simmel refers to

how life unfolds, intensies, and eervesces into more life, ultimately

augmenting, overcoming, and transcending itself into more-than-life.

As all of his major philosophical and exegetical writings indicate,

Simmel came to sociology only via an all-encompassing engagement

with the German classical humanistic tradition and the legacy of the

visions of social and self-formation, or Bildung, from Herder and

Goethe to Wilhelm von Humboldt. Robert Buttons essay in this issue

shows how the contemporary tragedy of culture for Simmel re-performs

and transforms ancient Greek motifs of resignation in the face of an

immutable destiny (moira) through modern meaning-making practices

which strive to make sense of accident, arbitrariness, danger, and

chance. In similar connections, Efraim Podoksiks contribution highlights how Simmels famous lecture on the modern metropolis and

mental life needs to be set against the background of a classical humanistic interest in the legacies of Roman antiquity, as illustrated by

Simmels three less well appreciated essays on the Italian cities of

Rome, Florence, and Venice. The three cities for Simmel suggest diering

images of unity and integration of the human collective creative mind in

its urban setting that become obscured or thrown into question under

conditions of modern industrialization with its dynamism of ruin and

renewal, even as they retain a symbolic validity as trans-historical reference-points for individual self-formation. Analogously, Donald N.

Levine pinpoints the continuous presence of Simmels engagement with

the writings of Kant and Goethe at all stages of his mature intellectual

development from the 1890s to his death in 1918. As Levine indicates, on

each occasion the great authors stand for Simmel as contrasting yet

ultimately complementary progenitors of two rival visions of unity and

division in the cosmos and society. Levines insight is crucial in showing

us how the social sciences and humanities are productively blended in

Simmels work to articulate the compelling norms of individual personhood that take shape out of lifes energies and emergent forms (see

also Levine, 1985; and Levines introduction with Daniel Silver to

Simmel, 2010).

Shortly after Simmels death, in Germany under the Weimar Republic

the question of the precise integration of humanistic education and social

science took on a heightened and more politicized signicance as the

governing coalition parties headed by the Social Democrats found themselves confronted with reactionary elements in the German professoriate

vehemently opposed to the demystication of long-dominant elite canons

of culture. This question would become an especially decisive preoccupation for the young Karl Mannheim, who, in Budapest in the spring of

1918, gave a lecture on Simmels thought entitled Soul and Culture

(translated from the Hungarian in this issue). As David Kettler points

out in his commentary on this address, Mannheim here takes up

16

Theory, Culture & Society 29(7/8)

Simmels theme of the crisis or tragedy of culture (Simmel, 1997

[1911]) in a novel way. In Mannheims subtly dialectical reading, soul

is, on the one hand, only a discourse of the age that reects a romantic

yearning for escape into putatively transcendent but essentially illusory

orders of being. But soul is also, on the other hand, an authentic expression of protest against rationalistic structures of social organization and

against reifying categories of perception that close down lifes potential

richness of sensuous understanding. As Kettler shows, the Simmelian

polarities of idealism and realism here become intertwined referencepoints for Mannheims diagnosis of the contradictions of European

societies over the course of the 1920s (see also Kettler, 1995; Loader

and Kettler, 2002).

Money, Sociality, and Precarious Life

In light of the return today of many of the features of degraded social

security and democratic breakdown that dominated European history in

the inter-war period, Simmels work speaks on many levels to the problem of a search for last fundaments of value for human social life and to

the impossibility of xing these fundaments in any determinate way. In

the face of capitalisms ever accelerating winds of creative destruction,

Simmels sense of the need and elusiveness of some denite anchoring

criterion of collective value in social life becomes more and more urgent.

In Simmels terms, which resonate with those used today, life consists in

self-evidently important qualities and experiences that need to be protected; yet life also turns out to be perpetually under construction, a

precarious product of always shifting and often conicting frames of

social transaction (cf. Butler, 2010). The resonant core of this problem,

which chimes with Simmels reections in The Philosophy of Money on

money-mediated processes of sociation and circulation, is that disputes

over value can never be expunged from public discussion about collective

ends. Several articles in this issue of Theory, Culture & Society respond to

this constellation of issues.

The relevance of this striking commutability in Simmels thinking

between the ow of life on the one hand and the ux of monetary transactions on the other stands at the forefront of Hans Blumenbergs brilliant essay on Simmel of 1976, translated into English here for the rst

time. Best known for a series of dense philosophical monographs on the

theory of myth and metaphor and on the concept of the legitimacy of

modernity in relation to antiquity and religious cognitive tradition,

Blumenberg (1985, 1988, 2010) was a close reader of Simmels works

until his death in 1996. For Blumenberg, the paradox at the heart of

Simmels corpus consists in arriving at a thematic of Life only via the

concept of money. In Blumenbergs suggestive formulation, money is

Simmels proto-metaphor for Life. The very phenomenon that might

Harrington and Kemple

17

seem most opposed to Life and to higher spiritual values is also the

phenomenon that most dynamically unlocks lifes plenitude of creative

forms even as it threatens constantly to destroy this plenitude through

eects of reication and objectication. As Blumenberg reads Simmel,

Life itself turns out to be pure circulation, sociation, and interactivity, an

endless cycle of extensions and intensications of value emerging through

processes of social exchange.

To be sure, any discussion of uctuation and uidity as features of

contemporary modernity runs a risk of false naturalization. It is important that any age of so-called liquid modernity, in Zygmunt Baumans

(2000) phrase, be seen in terms of a contingent product of complex yet

highly deliberate decision-making processes conducted at elite levels since

the 1970s, with the turn toward neoliberal global economic governance

policies. What often appears uid in this perspective is in many ways the

symptom of something that is the reverse of uid, namely rigid, doctrinaire and dictatorial. David Graebers recent account (2011) reminds us

that money is that invention of human civilization that attens out customary ties of economic reciprocity into rigid monetized debt relations

and takes on the veneer of a spurious moral authority in an age of global

nance capitalism and IMF-led structural adjustment programmes.

One of the many ironies of the global nancial crisis of 2008 in this

respect is that the banks and other nancial institutions at its centre

suddenly found themselves confronted not with too much but with too

little liquidity. The dynamic of liquefaction propelling the banks hegemonic nancialization of neoliberal economies the melting of all that is

solid into air now found itself faced with blockage and petrication.

The result has been that liquid modernity has come to look more and

more like an automobile running out of gas and spluttering to a halt. In

this regard, Simmels motifs of the ow and elan of modern life need to

be cross-checked with themes from Marx and Weber concerning political

economy and state power. Where for Simmel, and for the multifaceted

artistic and literary avant-garde movements of his day, vitalistic philosophical vocabularies once stood as forces of expressive protest against

the deadening hand of the capitalist market and techno-industrial civilization, today these same vocabularies are deployed to reinvigorate the

creative capitalist economy. Lebensphilosophie, having once been an

intellectual sub-culture of outsiders and romantic anti-capitalists,

becomes entrenched at the frontier of the contemporary entrepreneurial

culture (Boltanski and Chiapello, 2005; Lash, 2010).

It is partly this situation that Isabelle Darmon and Carlos Frade

address in their account of the scope of Simmels vision of reective

subjectivity for purposes of anti-capitalist critique today. On one level,

it is clear that the premium Simmel places on self-distance in multiple

arenas of social form renders problematic any simple appeal to a truer

self that needs to be liberated from inauthentic states of being under

18

Theory, Culture & Society 29(7/8)

capitalism. But as Darmon and Frade emphasize, Simmels project

cannot ultimately rest content with an ethos of lives led in diuse fragments and masks. Driving Simmels interest in mystic and religious

thought is a passionate search for the prospect of ontological unity

across multiplicity, where diverse lived experiences can be expressed

through shared commitments to life-enhancing social transformation,

including emancipatory political struggle. Nigel Dodds essay takes up

some of these questions by examining Simmels insight into the absence

of conceptually correct money in capitalist economies, that is, the lack

of a stable, neutral, and balanced standard of value. The inevitable disproportion between value and reality can also serve as a critical ideal for

assessing the shortcomings of liberal and socialist schemes of labour

money and just pricing, as Simmel does in The Philosophy of Money,

along with countless projects devised since then for micro-nancing, local

currencies, time-dollars, time-to-time credit, mutual nancing, and so on.

As Dodd argues, rather than presenting alternatives to the capitalist

money economy, these utopian schemes are just as likely to expose and

entrench its fundamental logic.

Further aspects of debates about globalization over the past 20 years

have revolved around the resurgence of regional, ethnic, and religious

identity politics and movements that react, sometimes violently, to

experiences of eroded social solidarity and security. It is useful here to

recall Simmels three famous sociological aprioris, from the canonical

Excursus on the Problem: How is Society Possible? inserted into the

opening chapter of Sociology, which examine the ontological unity of

social life despite the drift toward fragmentation (Simmel, 2009 [1908]:

4052; see Kemple, 2007). Simmels rst apriori, on the dynamics of

typication versus singularization, informs Gregor Fitzis contribution

to this issue, which proposes a novel way of thinking about the politics of

social solidarity in an age of ows of capital and people over national

boundaries. As Fitzi suggests, for all the talk today of the crisis of multiculturalism in mainstream political discourse, structures and practices of

social integration in complex interdependent global societies have in

many ways ceased to presuppose denite substantive values or norms

as preconditions for consensus building. In this sense they have

become, in Fitzis phrase, post-normative or trans-normative.

In a similar way, Simmels second apriori on the extremes of inclusion

and exclusion oers a perspective on the contradiction within the neoliberal project of capital accumulation and mobility: between the call for

open, transparent, corruption-free communication, on the one hand, and

the apparatuses of surveillance, security, and secrecy, on the other.

Charles Barbours contribution to this issue examines how Simmel

addresses these aporias of secrecy and mendacity in both collective and

personal terms, in a way that implies that the impossibility of society may

be ultimately constitutive of its possibility. Like Simmels curious poem

Harrington and Kemple

19

Only a Bridge and the piece, conceived as narrative fable, titled The

Maker of Lies (which Barbour discusses in some detail), the social relation and its pitfalls must be believed in and enacted rather than simply

declared or imagined. Both Barbours and Fitzis essays also suggest the

relevance of Simmels third apriori, on the tension between the force of

external necessity and the freedom of inner purpose, to contemporary

conditions. Following Simmel, they draw our attention to the reexive

process by which social relations are made possible as participants in a

collective become conscious of and actively synthesize a social unity

which does not wait for the sociologist and needs no spectator

(Simmel, 2009 [1908]: 41). Simmel assumes the dual experiential standpoint of the engaged observer and objective participant (or stranger)

who is marked o simultaneously as a part of and apart from intersecting

social circles, both inside the social whole as a subject of rights and

outside as an object of obligatory concern.

In all these connections, Simmels focus on individuality and individualization is relevant to current thinking about networked sociality and

the decline of conventional concepts of the social group predominant in

early post-war sociology. As Olli Pyythinen explores in this issue, in the

third chapter of The View of Life Simmel unfolds a vision of individual

self-identities that evolve through narrative relations to death a vision

strikingly redolent of Martin Heideggers famous conception of beingtoward-death in Being and Time, and indeed an explicit source of inspiration for the Black Forest philosopher in his early career, as rst documented by Michael Theunissen (1991). Pyyhtinen considers this vision of

individual selfhood from a sociological point of view as it emerges in

Simmels later life-philosophical writings, overlaying the rich spectrum of

contrasts he draws in his earlier works between the quantitative expansion of individuality on the one hand and its qualitative intensication

on the other, or between 18th-century egalitarian-mechanistic views on

the one side and 19th-century expressive-organic outlooks on the other

(Simmel, 1950 [1917]). Simmels preoccupation in his last years with a

third proto-existentialist conception of selfhood acutely raises the question of how an individual is to nd a sense of inner autotelic self-realization, even and especially in a lifeworld seemingly marked by thickening

webs of relations to the fragments, faces, or functions of other persons.

Neither a retreat back into 19th-century organic romantic outlooks on

the one hand, nor an appeal to Heideggers appeal to authentic Dasein

over against an anonymous mass of the They (das Man) on the other

hand, seem defensible options in this perspective.

In the last chapter of The View of Life Simmel formulates his concept

of the individual law (das individuelle Gesetz), understood as a search

for personal ethical self-justication without recourse to ready-made general moral precepts. Here we nd a broadly Nietzschean conception of

the importance of generalizable moral norms in modern times that

20

Theory, Culture & Society 29(7/8)

individuals can arm for themselves as sovereign personalities. In this

picture, Kants categorical imperative and by extension all conventional Judaeo-Christian moral doctrines fail to enable this quest for

personal ethical self-expression. As Daniel Silver and Monica Lee consider in their contribution to this issue, Simmels chapter on individual

law leaves readers asking themselves how these thoughts relate to

Simmels work from ten years previously on social structures and

forms of sociation. Silver and Lee attempt a response by showing how

The View of Life marks the nal stage in Simmels shift away from the

conventional Kantian sociology of morality that underlies his early writings from the 1890s, and that in large part continues in the work of

Durkheim. Both The View of Life and Sociology show Simmel in the

process of thinking through how the ethically mandated conduct of the

individual need not concur or coincide with the generalizable morality of

the collective of society, understood in Durkheims strong Kantian

sense. Simmels work in this regard shines light on recent debates in

philosophy over contextualist ethical worldviews (see, for example,

Williams, 1985), and in sociology over the problem of legislative moral

codes or frameworks (see, for example, Bauman, 1992). It also provides a

source for network analyses of the complex shifting character of dyadic

and triadic relations, and more generally of the quantitative conditioning

and objective conditions of modern social life. Like the naturalistic performances of La Duse, the famous Italian actress celebrated in one of

Simmels Snapshots (translated here), the ethical principle of action for

the modern individual can be expressed as a kind of stage direction or

inner imperative, namely, that the essence of the soul is movement.

***

Simmel was fortunately mistaken in believing that he would leave no

appreciable intellectual legacy, or that his ideas would not end up

being acknowledged as a signicant source for later thinkers. I know,

he wrote, in an oft-cited journal entry, that I shall die without spiritual

heirs (and this is good). The estate I leave is like cash distributed among

many heirs, each of whom puts his share to use in some trade that is

compatible with his nature but which can no longer be recognized as

coming from that estate (Simmel, 2010: 160; translation modied).

Simmels path-breaking diagnoses of the crises of European civilization at the beginning of the last century oer bridges and doors to an

understanding of the conditions of ux, contingency, and precariousness

that mark the fragmentary character of life in the early 21st century.

His manifold analyses of forms of sociation and individualization oer

rich resources for understanding cultures of individuality and their relation to systemic social logics today. The multi-disciplinary focus of the

Harrington and Kemple

21

articles brought together here highlights Simmels distinctive understanding of modernity not just in terms of a new aesthetic style or popular

fashion, but also as a mode of inner experience, sense perception, and

knowledge. What emerges is a challenging image of modernity dened by

the precarious, painful and perplexing aspects of contemporary existence.

Not only city streets, fashions, mealtimes, jewellery and seances but also

wars, revolutions and stock market crashes all these things confront us

with tasks of nding in each of lifes details the totality of its meaning,

as Simmel says in his Preface to The Philosophy of Money (1978 [1900/

1907]: 55). At issue are exemplary instances of modernity (Frisby,

1985b) that suggest synecdochal glimpses of the whole through its parts.

Thanks now to the publication of complete English translations of

Simmels three masterworks The Philosophy of Money of 1900/1907,

Sociology of 1908, and The View of Life of 1918 not to mention the

many shorter pieces which present us with new surprises, we can now

revise and rene our understanding of Simmel as a philosophical relativist or a post-modernist. As the contributions to this collection suggest, it

is impossible to settle on a portrait of Simmel as a philosophical aneur

leisurely strolling through the ruins of the modern metropolis, or of a

sociological bricoleur tinkering with the debris of the money economy to

project merely a miscellaneous collection of postmodern perspectives. It

would be misleading to conclude that Simmels eeting snapshots of

ordinary experience are not organized in a methodical way, or that

such fragmentary impressions of modern life never add up to a coherent

theoretical argument. Despite the impressionistic presentation of the

eclectic topics which make up the ten chapters of Sociology, for instance,

and the bewildering array of issues noted by Simmel in his index (which is

unfortunately omitted from the English translation; see Simmel, 1992

[1908]: 86575; Tyrell et al., 2011: 395406), Simmels stated objective

is to establish sociologys position in the system of the sciences and the

legitimacy of its cognitive purposes and methods, as he notes in his

Foreword (Simmel, 2009 [1908]: ix). Beneath its scintillating surface,

Simmels systematic corpus of works provides us with a sustained insight

into the preconditions for a fundamental interrogation of the bases of

value and meaning in contemporary capitalist societies. It is these systematic as well as essayistic, allegorical and aesthetic contours of

Simmels style of writing and thinking that this special section seeks to

illuminate.

Note

1. Mrs Oberlanders mother, Beate Jastrow, is on the far left behind the pear

tree; her aunt Ebith (Elisabeth) is hiding behind their mother, Anna Jastrow

(nee Seligman); her grandfather, Ignaz Jastrow, stands between Georg and

22

Theory, Culture & Society 29(7/8)

Gertrud Simmel (who wrote books under the name Maria Louise

Enkendorff). As fate would have it, this photograph was brought to

Thomas Kemples attention by a student in one of his undergraduate classes,

Rayka Kumru, who befriended Mrs Oberlander by chance on the ski slopes

of British Columbia.

Professor Ignaz Jastrow (18561937), a noted economist and historian at

the University of Berlin who published countless books and articles, and one

of the original members of the German Sociological Association along with

Simmel and Max Weber, was one of Simmels closest friends. Simmel reportedly called Jastrow the smartest man he ever met in his life, and the two were

said to engage in such long and intense conversations that the one could

hardly hear what the other one was saying (see the reminiscences of

Michael Landmann, Rudolf Pannwitz, and Fritz Jacobs, in Gassen and

Landmann, 1958: 13, 35, 170). Not long before this photograph was taken,

Simmel wrote an editorial, later printed in the October edition of the

Akademische Rundschau, protesting the firing of his friend from the staff of

the Berlin Handelshochschule which Jastrow helped to found. Jastrows dismissal was ostensibly on financial grounds, but in Simmels view it was

carried out in a way which threatened the academic freedom of university

lecturers and could lead to the commodification of higher learning (Simmel,

2005 [1914]); see the editors remarks on pp. 4635).

In a note on the back of the snapshot reproduced on the cover, Beate

Jastow recalls the characteristic movements Simmel typically made when

speaking, a peculiarity many of his students remarked on as well: His

voice, apparently slightly laborious, his language and art of speaking, were

incomparable, completely original. His voice circled around the object so to

speak, encircling it, holding, vibrating and then raising a little, intoning

strangely and finally wrapping itself in the object, boring into it; it matched

his form of thought exactly, this process of winding, slowly unwinding, everything he concerned himself with. He shaped things so that they assumed and

expressed his incomparable spirit, but at the same time reflected their own

essence and truth (Richard Kroner in Gassen and Landmann, 1958: 228;

translated in Stewart, 1999: 7; see also Fechter in Gassen and Landmann,

1958: 160; and Salz, 1959: 235).

In his unpublished Autobiographical Sketch of 1920, Jastrow comments

that even as Simmels influence and reputation began to grow after his death,

the most deeply and uniquely influenced by him were those who knew him

personally. With the most composed of gazes he would find a concept and a

context for every object he beheld or contemplated, taking his audience with

him into philosophical heights and depths, and all the while ready to offer his

brilliant mental counsel to others without any desire to show off or impress

(quoted by Otthein Rammstedt in note 3 of his essay in this issue). Although

Simmel had little to say about the musical arts, he seems to have embodied

their rhythms and movements in the way that he orchestrated words, ideas,

and gestures in the lecture hall; conducted them in everyday conversation; or

composed them on the written page (see Simmel, 2010 [1918]: 47; Kemple,

2009: 1958).

Harrington and Kemple

23

References

Bauman, Zygmunt (1992) Postmodern Ethics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bauman, Zygmunt (1993) Life in Fragments: Essays in Postmodern Morality.

Oxford: Blackwell.

Bauman, Zygmunt (2000) Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Blumenberg, Hans (2010 [1960]) Paradigm for a Metaphorology, trans. and intro.

Robert Savage. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Blumenberg, Hans (1985 [1966]) The Legitimacy of the Modern Age, trans. and

intro. Robert Wallace. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Blumenberg, Hans (1988 [1978]) Work on Myth, trans. and intro.

Robert Wallace. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Boltanski, Luc and E`ve Chiapello (2005) The New Spirit of Capitalism, trans.

Gregory Elliott. London: Verso.

Butler, Judith (2010) Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? London and New

York: Verso.

Castoriadis, Cornelius (1997) World in Fragments: Writings on Politics, Society,

Psychoanalysis, and the Imagination, trans. and ed. David Ames Curtis.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Deleuze, Gilles (1997) Immanence: A Life (trans. Nick Millet), Theory, Culture

& Society 14(23): 37.

Deleuze, Gilles (2001) Pure Immanence: Essays on a Life, trans. Anne Boyman.

New York: Zone.

Fischer, Joachim (2008) Philosophische Anthropologie: Eine Denkrichtung des 20.

Jahrhunderts. Freiburg: Alber.

Frisby, David (1981) Snapshots sub specie aeternitatis?, pp. 103131 in

Sociological Impressionism. London: Heinemann.

Frisby, David (1985a) Georg Simmel: First Sociologist of Modernity, Theory,

Culture & Society 2(3): 4967.

Frisby, David (1985b) Fragments of Modernity: Theories of Modernity in the

Work of Simmel, Kracauer, and Benjamin. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Frisby, David (1992) Simmel and Since. New York: Routledge.

Gassen, K. and M. Landmann (eds) (1958) Buch des Dankes an Georg Simmel.

Berlin: Kunker und Humblot.

Graeber, David (2011) Debt: The First Five Thousand Years. New York: Melville

House.

Habermas, Jurgen (1994 [1988]) Postmetaphysical Thinking, trans. W.M.

Hohengarten. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Harman, Graham (2005) Guerrilla Metaphysics: Phenomenology and the

Carpentry of Things. Chicago and Lasalle, IL: Open Court.

Harrington, Austin (2011) Simmel und die Religionssoziologie, in Otthein

Rammstedt, Ingo Meyer and Hartmann Tyrell (eds) Georg Simmels groe

Soziologie: Eine kritische Sichtung nach hundert Jahren. Bielefeld:

Transkript Verlag.

Harrington, Austin (2012) Von der intellektuellen Rechtschaffenheit zur

taghellen Mystik: Aspekte und Differenzen einer Glaubenskonzeption bei

Max Weber, Georg Simmel und Robert Musil, in Gerald Hartung und

24

Theory, Culture & Society 29(7/8)

Magnus Schlette (eds) Religiositat und Intellektuelle Redlichkeit. Tubingen:

Mohr-Siebeck.

Kantorowitz, Gertrud (1959) Preface to Georg Simmels Fragments,

Posthumous Essays, and Publications of his Last Years, pp. 99123 in

Georg Simmel, 18581919, trans. and ed. Kurt H. Wolff. Columbus, OH:

Ohio State University Press.

Kemple, Thomas M. (2007) Allosociality: Bridges and Doors to Simmels Social

Theory of the Limit, Theory, Culture & Society 24(78): 119.

Kemple, Thomas M. (2009) Weber/Simmel/Du Bois: Musical Thirds of

Classical Sociology, Journal of Classical Sociology 9(14): 183203.

Kemple, Thomas M. (2010) Introduction to David Frisbys TCS Articles,

Theory, Culture & Society special commemorative e-issue on the work of

David Frisby. Available at: http://theoryculturesociety.blogspot.com/2010/

12/photo-david-frisby-in-commemoration-of.html.

Kettler, David (1995) Karl Mannheim and the Crisis of Liberalism: The Secret of

These New Times. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Krech, Volkhard (1998) Georg Simmels Religionstheorie. Tubingen: Mohr

Siebeck.

Lash, Scott (2005) Lebenssoziologie: Georg Simmel in the Information Age,

Theory, Culture & Society 22(3): 124.

Lash, Scott (2010) Intensive Culture: Social Theory, Religion and Contemporary

Capitalism. London: SAGE.

Latour, Bruno (2005) Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network

Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Levine, Donald N. (1985) Flight from Ambiguity: Essays in Social and Cultural

Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Loader, Colin and David Kettler (2002) Karl Mannheims Sociology as Political

Education. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Lukacs, Georg (2010 [1911]) Soul and Form, trans. Anna Bostock, eds. John T.

Sanders, and Katie Terezakis, intro. Judith Butler. New York: Columbia

University Press.

Mannheim, Karl (1936) Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of

Knowledge, trans. Louis Wirth and Edward Shils. New York: Harcourt,

Brace & World.

Rammstedt, Otthein (1991) On Simmels Aesthetics: Argumentation in the

Journal Jugend, 18971906, Theory, Culture & Society 8: 125144.

Salz, Arthur (1959) A Note from a Student of Simmels, in Georg Simmel,

19581918, ed. and trans. Kurt H. Wolff. Columbus: Ohio State University

Press.

Schutz, Alfred (1966) On Multiple Realities, Collected Papers, vol. 2. The

Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Simmel, Georg (1950 [1917]) Basic Problems in Sociology (Individual and

Society), in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. and trans. Kurt H. Wolff.

New York: The Free Press.

Simmel, Georg (1990 [1900/1907]) The Philosophy of Money, trans. Tom

Bottomore and David Frisby. London: Routledge.

Simmel, Georg (1992 [1895]) Bocklins Landschaften, pp. 96104 in Georg

Simmel Gesamtausgabe, vol. 5, eds. Hans-Jurgen Dahme and David P.

Frisby. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Harrington and Kemple

25

Simmel, Georg (1997 [1911]) The Concept and the Tragedy of Culture, in

Simmel on Culture, trans. Mark Ritter and David Frisby, eds. David Frisby

and Mike Featherstone. London: SAGE.

Simmel, Georg (2005 [1914]) Der Fall Jastrow, pp. 115118 in Klaus Christian

Kohnke with Cornelia Jaenichen and Erwin Schullerus (eds) Georg Simmel

Gesamtausgabe, vol. 17. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Simmel, Georg (2009 [1908]) Sociology: Inquiries into the Construction of Social

Forms (2 vols), ed. and trans. Anthony J. Blasi, Anton K. Jacobs and

Matthew Kanjiranthinkal; intro. Horst J. Helle. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Simmel, Georg (2010 [1918]) The View of Life: Four Metaphysical Essays with

Journal Aphorisms, trans. Donald N. Levine and John A.Y. Andrews; intro.

Donald N. Levine and Daniel Silver. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stewart, Janet (1999) Georg Simmel at the Lectern: The Lecture as

Embodiment of Text, Body & Society 5(4): 116.

Theunissen, Michael (1991) Negative Theologie der Zeit. Frankfurt am Main:

Suhrkamp.

Tyrell, Hartmann (2007) Georg Simmels groe Soziologie (1908): Einige

Uberlegungen anlalich des bevorstehenden 100. Geburtstags, Simmel

Studies 17: 540.

Tyrell, Hartmann, Otthein Rammstedt and Ingo Meyer (eds) (2011) Georg

Simmels groe Soziologie: Eine kritische Sichtung nach hundert Jahren,

Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Williams, Bernard (1985) Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Austin Harrington is Reader in Sociology at the University of Leeds. For

seven years he taught in Germany at the University of Erfurt and the

European University in Frankfurt an der Oder. His publications include

Art and Social Theory (Polity Press, 2004) and Modern Social Theory: An

Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2005, editor). He is completing a

monograph on Weimar and European thought, to be titled, provisionally, Social Theory in Western Civilization: The German Liberal Voice in

European Ideas, 1914 to the Present.

Thomas M. Kemple teaches social and cultural theory at the University of

British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. His recent work on the intersections of classical and contemporary theory has appeared in Theory,

Culture & Society (including the special section on Simmels aesthetics,

ethics, and metaphysics in 2007), Journal of Classical Sociology,

Sociologie et societes, and Max Weber Studies.

Вам также может понравиться

- Theory Culture Society 2005 Lash 1 23Документ23 страницыTheory Culture Society 2005 Lash 1 23rifqi235Оценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Social Compass 1999 NIELSENДокумент15 страницSocial Compass 1999 NIELSENrifqi235Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Theory Culture Society 2007 Bleicher 139 58Документ20 страницTheory Culture Society 2007 Bleicher 139 58rifqi235Оценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- European Journal of Social TheoryДокумент10 страницEuropean Journal of Social Theoryrifqi235Оценок пока нет

- Flow The Psychology of Optimal ExperienceДокумент9 страницFlow The Psychology of Optimal Experiencerifqi235100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Heidegger Authenticity and The Self Themes From Division Two of Being and Time PDFДокумент5 страницHeidegger Authenticity and The Self Themes From Division Two of Being and Time PDFrifqi235Оценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- An Introduction To Hermeneutic PhenomenologyДокумент9 страницAn Introduction To Hermeneutic Phenomenologyrifqi235100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The ThinkingДокумент22 страницыThe Thinkingrifqi235Оценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Heidegger and AuthenticДокумент4 страницыHeidegger and Authenticrifqi235Оценок пока нет

- Intersubjectivity, Subjectivism, Social Sciences, and The Austrian School of EconomicsДокумент27 страницIntersubjectivity, Subjectivism, Social Sciences, and The Austrian School of Economicsrifqi235Оценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Phenomenology Wiki PDFДокумент159 страницPhenomenology Wiki PDFrifqi235Оценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Chalice of Eternity - An Orthodox Theology of Time - Gallaher BrandonДокумент9 страницChalice of Eternity - An Orthodox Theology of Time - Gallaher BrandonVasile AlupeiОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Riles Annelise Network Inside Out COMPLETOДокумент133 страницыRiles Annelise Network Inside Out COMPLETOIana Lopes AlvarezОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Art and Myth of The Ancient Maya PDFДокумент303 страницыArt and Myth of The Ancient Maya PDFjanicemartins100% (6)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Communication of WhistlingДокумент10 страницThe Communication of WhistlingjennifermgОценок пока нет

- Reader's Guide: The Mind of The South - W. J.Документ40 страницReader's Guide: The Mind of The South - W. J.CocceiusОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- 1Документ472 страницы1Febri Tie Yan100% (1)

- Guha 1998Документ20 страницGuha 1998sodolakpoupanmeiОценок пока нет

- BOHANNAN, Paul. Introduction. In. Beyond The Frontier - Social Process and Cultural Change.Документ7 страницBOHANNAN, Paul. Introduction. In. Beyond The Frontier - Social Process and Cultural Change.WemersonFerreiraОценок пока нет

- Moffitt - Inspiration Bacchus and The Cultural History of A Creation MythДокумент426 страницMoffitt - Inspiration Bacchus and The Cultural History of A Creation MythChiara l'HibouОценок пока нет

- 5 StagesДокумент1 страница5 StagesDaniel Garzia AizragОценок пока нет

- Chapter 4 Final DefenseДокумент41 страницаChapter 4 Final Defenseshienna baccay100% (1)

- Complete The Sentences With The Correct PrepositionДокумент2 страницыComplete The Sentences With The Correct PrepositionOlivera MajstorovicОценок пока нет

- Islamic PsychologyДокумент12 страницIslamic PsychologyMissDurani100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Linguistic Landscapes in The PhilippinesДокумент6 страницLinguistic Landscapes in The PhilippinesAmiel DemetrialОценок пока нет

- Orlove 1980 PDFДокумент40 страницOrlove 1980 PDFAndrezza PereiraОценок пока нет

- Central Concepts of LinguisticsДокумент5 страницCentral Concepts of LinguisticsAsma NisaОценок пока нет

- Sociological Perspective of SexualityДокумент44 страницыSociological Perspective of SexualityMatin Ahmad KhanОценок пока нет

- Edinburgh University PressДокумент34 страницыEdinburgh University PressAlin HențОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Nelson 2014 El Camino Desde La Primera Infancia A La Comunidad de Mentes CompartidasДокумент14 страницNelson 2014 El Camino Desde La Primera Infancia A La Comunidad de Mentes CompartidasSebastián Fonseca OyarzúnОценок пока нет

- The Ethnopharmacology of AyahuascaДокумент94 страницыThe Ethnopharmacology of AyahuascaÓskar Viðarsson100% (1)

- Teaching Sociolinguistic Competence in The ESL ClassroomДокумент69 страницTeaching Sociolinguistic Competence in The ESL Classroomlmcrg1971100% (1)

- Phenomenology, Psychotherapy, Psychosis and Normality: The Work of Eva SyristovaДокумент8 страницPhenomenology, Psychotherapy, Psychosis and Normality: The Work of Eva SyristovaEdwardGardner100% (1)

- Week 1 DissДокумент26 страницWeek 1 DissJhoe SamОценок пока нет

- Arizona's GoblinsДокумент1 страницаArizona's GoblinsJoe DurwinОценок пока нет

- Mead and Bali DanceДокумент27 страницMead and Bali Dancedario lemoliОценок пока нет

- Joseph Campbell: Myths Missing The MarkДокумент11 страницJoseph Campbell: Myths Missing The MarkRussell York100% (1)

- Death Without WeepingДокумент5 страницDeath Without WeepingLeonardo Gonzalez HerreraОценок пока нет

- Broadbent Function and Symbolism in ArchДокумент23 страницыBroadbent Function and Symbolism in ArchMohammed Gism AllahОценок пока нет

- The Case of The Missing AncestorДокумент8 страницThe Case of The Missing AncestorCésar GarcíaОценок пока нет

- Decentering The RenaissanceДокумент400 страницDecentering The RenaissanceTemirbek BolotОценок пока нет