Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Lacan Goes Business Carl Cederström

Загружено:

maricela_clasesОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Lacan Goes Business Carl Cederström

Загружено:

maricela_clasesАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Cederstrm, C.

(2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

LACAN GOES BUSINESS

Carl Cederstrm

Introduction

Management studies and psychoanalysis seem to make an odd cocktail, not

because management lacks a pathological basis everyone knows that

management is pathological by nature, having as its elementary goal to

effectively subdue and refine human resources but because they stem

from radically different backgrounds, sharing no common language. If

psychoanalysis can be described as a practice and theory of the shadier

sides of the human subject (by which I mean all that stuff which is easy to

sense, yet difficult to admit, including unconscious desires, guilt, sexuality,

and death wishes), then management is a practice of suppression and

blissful denial. It is clear to anyone familiar with management literature that

words such as enjoyment, desire and even fantasy are passed over in

silence, replaced by a cheerful, inspiring and easy-going set of words (of

which motivation is probably the most popular). But this language barrier,

important as it might be, is not the most obvious problem. What makes

management theory so incompatible with psychoanalysis is related to a

more fundamental concern, that of the human subject. Whereas

psychoanalysis has brought the inexorable inconsistencies of the self to the

surface, convincingly revealing that the ego is not master in its own house,

management studies continue to assume the existence of a rational, asexual

and sensible self, miraculously acting in accordance with its own,

individual, intentions.

It might thus seem strange that management has recently turned to

psychoanalysis, more precisely Lacanian psychoanalysis, to further explore

the world of organizations and the art of management. My ambition with

this paper is to show that this turn is not as surprising as it might first

appear. In order to make this point I will begin, in the first section, by

sketching a hasty and rather crude picture of the academic landscape in

which management is couched. The purpose is by no means to make a fair

and thorough characterization, but, as with all hasty sketches, to exaggerate

some features, shamelessly omitting others, with the hope of capturing

something of the heart, or spirit, of my subject.

Albeit brief and superficial, the sketch reveals that the growing

interest in Lacan stems from a stream called Critical Management Studies

and their recent interest in the work of Foucault. Following from this is a

16

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

critical reading of five texts all of which try to show the relevance of

Lacans work for studying organizations. In the final section I will dwell on

some of the most obvious and perennial problems that follow from

transferring a set of ideas from one (in this case very particular) setting to

another: the risk of misrepresentation and oversimplification, as well as not

being sensitive to the origin and specificities of the ideas.

17

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

I

Let me begin by making a rather crude division of management studies,

dividing the field into two extremes1. On the one extreme we find the (diehard) conservatives. These men (most of them are men) are recognized by

their cautious countenances and unshakable fidelity to economic theory.

They love to speak about new innovative start-ups and rapidly growing

markets in Asia. In fact they are, with very few exceptions, Asiaphiles:

frequently travelling to China and India, politically engaging themselves in

questions concerning emerging markets and free trade. As a rule, they are

well-versed in economic theory (knowing their Taylor, Simon and Williamson

by heart) and diligently following the recent trends in the economic

landscape, keeping themselves up-to-date by subscriptions to The Wall

Street Journal, Financial Times, The Economist, Fortune etc.

What is most amusing with these conservatives is that they, when

feeling youthful and self-confident, emboldened by a somewhat strange

conviction of being anti-conservative, even hip, suddenly begin to call

themselves gurus. (Or better, they have someone else call them gurus and,

in an air of false-modesty, refrain from protesting).

Under the influence of this conviction a number of books have been

authored, some of which carry more subtle titles than others. Among the

most famous (but not most subtle) we find The New Age of Innovation,

Leading the Revolution and Good to Great. Based on elementary insights

of business strategy, written in a straightforward and stylish way, and

delivered with the fervour of a preacher, these business gurus have

composed a recipe so commercially successful that no business-class

commuter with self-respect could avoid buying (into) these books.

The backdrop against which these books make their groundbreaking

points, often conveniently summed up in five or ten lessons (or even

commandments, which even further underscores the proximity between

business jargon and sermons), are case studies of miraculous dimensions.

As a rule these stories follow a few passionate youngsters from a provincial

town who, bored and/or socially excluded, decide to invent something in

someones garage. It becomes a success and gradually, or rather explosively,

these boys or girls become CEOs of multinational corporations worth

billions of dollars. Even if the subject of these books is the art of business

Since I am addressing an audience that has probably (and in that case luckily) been

spared from most academic babble on management, at the very least not having endured

sleepless nights trying to work out the difference between resources and competences, I

shall take this opportunity to be rather unfair. This does not mean that the characterization

will be any less accurate, only that some would have wished for a more nuanced, intricate

and sophisticated picture, than the one I will now offer.

1

18

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

strategy, and why some corporations end up being more successful than

others, it is hard to believe that these books would have gained even near as

much attention were it not for its appeal to an imaginary register. It is quite

clear I would say that the undercurrent of these stories, and what makes

them captivating, is well-known fantasmatic archetypes of the weak and the

strong, David and Goliath, or why not the modern American version, the

revenge of the nerds. To be sure, drawing on these popular fantasies seem

to work just as fine for business as for any other context, surely evoking a

flood of sentimentality, filling all eager beavers with syrup feelings of

excitations.

Even though there is a good deal of radical posturing at work in these

business books, it is nevertheless the case that the conservatives, just as

the name implies, defends a number of conservative standpoints. They

always tend to side with the market, remaining conspicuously uncritical

towards central political issues (such as domination, exploitation,

globalization and owner patterns, etc.) and abundantly critical towards

social and political theory, particularly so-called postmodern theory. Thus,

in their effort to preserve a theory of management, shielded from fads and

unnecessary posturing, this circle of scholars have tended to scorn

speculative and excessive methods while hailing the art of crafting strict

and rigid analyses. There are of course exceptions to this rule. Some

conservatives have momentarily left the bounds of their own field, searching

for inspiration and new ideas in unknown territories. But these adventures

have, as a rule, remained unadventurous, not going much further than

declaring that there might be something valuable to learn, on a

metaphorical level. The academic field of choice is also quite predictable,

most commonly being (cognitive and social) psychology and natural science,

fields with which conservative management scholars seem to feel an

elementary form of kinship, that is, a shared admiration for positivism and

quantitative methods.

Their Victorianism is not limited to their work, but comes back in their

appearance. Armies of cloned conservatives march around American

management conferences like phantoms. They all look the same. With their

solemn faces and grey moustaches they are indistinguishable. Their suits

are dark and rather expensive, but not tailor-made. Instead they belong to

the category of suits which aim to express nothing but austere nothingness,

that is: rather baggy, with colourless colours and shapeless shapes.

So what about the typical critical management scholar? Let me just

say that even though they might share the same common rooms with the

conservatives, maybe even the same coffee-machine, they certainly dont

share their ideals at least not openly. Their clothes are also quite different.

Suits are taboo. And so are moustaches. A more appropriate outfit would

19

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

consist of a flowery but not too flowery shirt something like a Hawaii-shirt

with quiet colours a pair of faintly flared jeans and semi-arty glasses. Most

importantly, however, is that all clothes have to be worn nonchalantly, as if

representing a necessary evil, a social convention to which even these

critical souls have to adhere. All in all, the clothes should be selected and

worn in such a way that no one would fail to recognize that to them, clothes

are essentially part of a shit consumerist ideology.

Rather than gated communities in the US, these scholars live in the

UK, preferably in East London. They dont own cars. Instead they travel by

train or bike. They are often mixed up with some kind of social movement, at

times coming along to demonstrations, but generally remaining distant from

the cross-fire2. Most characteristic, however, is the kind of guilt complex

which seems to be a vital aspect of their revolutionary zeal. In fact, they tend

to have as strong a desire to speak of their intellectual and political

involvements as to conceal their intellectual and political background (it is

rare that a critical scholar has a flattering history: most of them began their

academic studies with the shameful fantasy of becoming successful

consultants, something of which they now try to pass over in silence).

At any rate, this band of lively and daring scholars has had

considerable impact on the field, causing quite a lot of trouble. They have

arrogantly rebelled against their conservative siblings. And they have been

quite successful. Promiscuously turning to disciplines other than its own,

and feverishly embracing a number of social and political theorists, they

have even managed to redefine management studies, broadening the horizon

such that it has now becomes a sort of melting point, where a strange

variety of traditions coalesce.

A common feature, which has run as a leitmotif through the relatively

recent history of critical management studies, is the ambition to unearth

dominant and suppressive power relations. Whether the focus lies on the

exploitation of blue-collar workers, the surveillance of call-centre agents, or

the ideological control over consultants, the aim has remained staunch: to

show how the work organization engenders and re-produces repressive, at

times even pernicious, conditions.

The historical side of CMS is a funny, perhaps ironic, affair. When

Margaret Thatcher took arms against the sociology departments in the

1980s, aiming to get rid of all muzzy Marxists, she made something of a

mistake. Even though she splendidly accomplished to kick all sociologists

out on the street, she failed to keep them there. Not before long business

schools and management departments began to be filled with sociologists.

The close relation between CMS and anti-globalization social movements is obvious from

the journal Ephemera. See particularly the special issue on The Organisation and Politics of

Social Forums, volume 5, number 2 (may 2005),

http://www.ephemeraweb.org/journal/52/5-2index.htm

20

2

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

So the great diaspora from the sociology departments took an unanticipated

turn and ended in a new Marxist establishment, with the business school as

the new headquarter:

Thatchers class offensive had the humorous and unintentional

consequence of putting Karl Marx on the business education

curriculum, usually under the innocuous guise of Organization

Behaviour. (Fleming, 2009)

However, critical analyses of management go back a long time long before

Thatcher was born at least as far as 1776 when Adam Smiths The wealth

of nations was published (see Fournier and Grey, 2000: 9). But critical

management studies as a joint project is a fairly new invention. It is not until

the 1990s, particularly with the publication of Critical Management Studies,

edited by Alvesson and Willmott, in 1992, that it is even possible to speak of

a unified group, assembled under one name.

Though sharing the same name, this group is heterogeneous in

nature: consisting of many strands, influences and trajectories some of

which might be mutually exclusive with regard to particular theoretical

areas. However, three big names obsessively return whenever CMS is

mentioned, namely Marx, Weber and Foucault (see Fleming, 2009). They

represent the history of CMS, in chronological order. Marx appeared in the

1970s, via labour process theory, and became an important figure

throughout the 80s and 90s. These texts produced a number of critical

reflections on the organization, foregrounding sensitive issues of deskilling

and mechanization. The work of Weber has also been widely used in critical

management accounts, particularly in relation to Marxian themes such as

control, ideology, and exploitation. The third figure, Foucault, is particularly

interesting for our purpose. To begin with, it has been argued that it is only

with the entrance, and subsequent diffusion, of Foucauldian themes that

CMS has gained a recognizable and influential voice (Fleming, 2009).

Equipped with a novel and in many ways original theoretical battery a surge

of critical management scholars began, in the beginning/mid 90s, to level a

profound critique not only against oppressive management techniques but

also against those basic presuppositions which, up until that point, had

been unquestioned. In a seminal paper from 1992, Alvesson and Willmott

presented a critical diagnosis, suggesting that CMS was gradually moving

down an unholy road, marked by essentialism, intellectualism and

negativism. To counter these tendencies, and to open up novel avenues, they

suggested that critical theory had to open itself up to a number of influences

in order to reinvigorate the original objectives of emancipation and equality.

They urgently called for a novel and open dialogue, between Critical

21

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

Theorists' commitment to critical reason and radical change, the skepticism

of poststructuralists about metanarratives and efforts to separate power and

knowledge, and humanistic ideas for reducing the gap between human

needs and corporate objectives (Alvesson and Willmott, 1992b, p.461).

In spite of his popularity, Foucault has become something of a

scapegoat. Even though he never advocated pure relativism, linguistic

determinism or idealism, his name has nevertheless become intimately

bound up with these ideas. Whether these accusations should be seen in

the light of a somewhat problematic interpretation of Foucaults work (where

his work at times becomes so ill-interpreted that it would seem to be nothing

but postmodern relativism) or in relation to the conservative nature of the

field (where gatekeepers push aside and scorn all unconventional theories) is

by no means clear. Either way, some critics have it that the poststructuralist

invasion has aestheticized criticism, that is, made it toothless and purely

stylish.

It should come as no surprise that the recent interest in Lacan comes

particularly from these scholars, interested not only in CMS but also

poststructuralism. Lacan can thus be seen as yet another exotic figure,

alongside Foucault. In the following section I shall describe, in some detail,

the ways in which Lacan has been integrated into critical analyses of

management.

II

Like all rapidly growing movements, the management Lacanians have

developed in various directions. Some have exclusively focused on a single

Lacanian concept; others have focused on particular periods or particular

key texts; others still have tried, more broadly and perhaps more

ambitiously, to draw on the whole Lacanian oeuvre, claiming that the legacy

of Lacanian psychoanalysis should be conceived as a whole, and that, as a

consequence, his early work must be seen in the light of his later

developments, and vice versa.

Even though this growing strand lacks a quilting point, it would be

somewhat unfair to say that the marriage between Lacan and management

has culminated in an unhealthy relation of delusional psychosis. In this

section it is my aim to show that there are, in spite of all the differences, a

number of traits that hold this novel collection of texts together. Surely I

would not argue that they constitute a stable and discrete category, with

well-articulated premises, but only that they share a number of objectives,

in that they all seek to extend the critical inquiries of organizations, taking

the important lessons from Marxism and poststructuralism one step further.

Of course this is a difficult thing to do. Not only is there a risk of

22

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

appropriation, by which the work of Lacan would too liberally be adapted to

various purposes, but also of misrepresentation and hasty projections.

To provide a provisional idea of how Lacan has entered into

management studies I will present five texts which, in recent times, have

appeared in major management and/or organization journals. While each of

these texts presents distinct approaches to Lacan, they come together in a

number of ways. First they take on a critical standpoint, trying to illuminate

certain political and ideological aspects of organizational life, particularly the

notions of social control and disciplinary processes. Second, they depart

from a poststructuralist position, claiming that Lacan can take us even

further. Third they focus on the question of identity and how the modern

work-place is in a continual process of crafting new and alluring identities,

by which employees behaviour may be regulated.

In his article, The Power of the Imaginary, John Roberts takes up the

issue of social control and the role that images and processes of

identification play in effecting such control (2005: 619). In many ways a

typical article written in the CMS tradition, beginning with a reading of a

number of influential texts in the CMS literature, Roberts register the almost

infinite ways in which control is exercised: as self-discipline, as

internalization, as identification with a normative ideal or ethic, as an effect

of discourse, or as an existential need for the closure of identity. Roberts

then moves on to claim that Foucault, through his work on visibility, allows

for a somewhat alternative interpretation of control. He claims that the

process through which a person becomes seen, subjected to a gaze, is quite

sensitive in that it throws the subject into a vulnerable sphere, into a field

of visibility. Subjection to the gaze is thus, according to Roberts, subjection

to power insofar as being seen, or recognized, produces a narcissistic

sensation on part of the recognized, which, by extension, makes him or her

susceptible to control.

As with all identifications the different images of control each offers us

an alluring moment of recognition that is offered and perhaps grasped

as the truth of the self but then collapses into its opposite. (2005, p.

627)

It is at this stage that Roberts wishes to introduce Lacan (more precisely

Lacans early text The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function) claiming

that the force of Lacans analysis is to point to the power of the image as a

lure or trap (2005, p. 636). The set up is thus clear: control is a widely

researched topic within (critical) management, and Lacans idea of the mirror

stage can bring us a better understanding of why we become ensnared in the

mesh of organizational norms and values. If the set up is abundantly clear,

23

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

providing new insights into how control may be exercised or produced, then

the reading of Lacan is less so. In his description of the Lacanian subject

Roberts says:

On the one hand, it is an account of the foundation of a humanist,

interiorized self; of a sense of self as a discrete, autonomous,

independent entity. On the other hand, it is an account of the illusions

or misunderstandings of the humanist conception of the self (2005,

p.627)

It is not that this portrayal is all wrong, but rather that it might produce the

deceptive idea that Lacan was even slightly sympathetic towards the notion

of a humanist, interiorized self. It is clear, however, that Lacan fervently

turned against any such notion. To him the ego emanates fromthe

subjects impotence (Lacan, 1991, p.50) and not by any means from a

discrete, autonomous, independent entity. Roberts gives no account of how

to separate the ego from the subject, nor does he show how the Other (as

correlate to the subject) is something quite different from the other (as

correlate to the ego). Important or not for Roberts purpose, these aspects

are crucial according to many Lacanians which begs the question of

interpretation and the nature of representation. Is it necessary to include a

rich set of details in order to make a fair and ample representation of a

theory? Or is it merely enough to include what serves an overarching

purpose? Further: are these details pertinent to this particular setting, or

should they rather be seen as obsessive and futile hair-splitting on part of

constrained dogmatists? In this case, Roberts makes clear that, to him, this

dual understanding of the ego as both the affirmation and the critique of a

humanist conception of the self allows us to understand the social

character of control, even whilst this is denied by the ego. Further, he

claims that:

the success of these new individualizing practices of management

control lies precisely in the power of recognition as a lure or trap in

which employees seek and seem to find the self, but it also requires a

new site into which all that is inadequate can be placed (2005. p.635).

Thus: we are vulnerable to processes of subjection because they offer

confirmation of our existence (2005, p.636). This argument is certainly

pertinent to the way in which control plays itself out, and in this sense also

a valuable contribution to the on-going debate of how modern corporations

present ever new techniques for subordinating employees. But would it be

necessary to turn to Lacan in order to make this argument? The fact that

24

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

recognition is somewhat fraudulent is just that, a fact. There is more than

one philosopher who has made this point. Hegels slave-master dialectic, for

example, clearly reveals the inexorable complexity of recognition 3. We might

also add that there is hardly any love novel (the most sleazy and simpleminded love novels excluded) that does not make an obligatory reference to

the narcissistic overtones of love, where the lover suddenly realizes, to his

great despair, that what he really loved was not his love object but the

reflection of himself in that very love object4.

However, Roberts is not simply content with pointing out that

recognition might be a dangerous thing, but goes on to say that any

recognition will always turn out to be misrecognition, adding that we look

for recognition not just as confirmation of our existence but also as evidence

of the worthiness of our existence (2005, p. 636). Situating the function of

misrecognition in the context of the work-place, Roberts makes an

interesting and valuable point: namely how employees, by identifying

themselves with an image of unity, become more vulnerable to managerial

control.

Like Roberts, Harding (2007) concentrates on Lacans early (and very

short) text on the mirror stage. In her essay, published in the journal

Organization Studies, she gives a detailed account of an interview, conducted

with a busy career woman, working for the National Health Service. The

central theoretical concept, from which the paper takes its cue, and which

she attempts to develop, is that of becoming-ness. Following one of the most

established arguments within postmodern theory, Harding suggests that

the organization, rather than being conceived as a noun, should be

appreciated as a verb, constantly renewing itself. Along the same lines she

goes on to argue that the organizational members are part of the

organization as much as the organization is part of its members:

there is no distinction between organizational members and

organizations: organizations and individuals are unstable effects that

are each enfolded into the other.(2007: 1761)

In Alexandre Kojves reading of Hegel, recognition is the basis for the dialectic between

the master and the slave. Kojeve writes He must give up his desire and satisfy the desire of

the other: he must recognize the other without being recognized by him. Now, to

recognize him thus is to recognize him as his Master and to recognize himself and to be

recognized as the Masters Slave (Kojve, 1980, p.8)

4

This is particularly obvious in Prousts masterpiece In Search of Lost Time, where he

writes: When we are in love, our love is too big a thing for us to be able altogether to

contain it within us. It radiates towards the beloved object, finds in her a surface which

arrests it, forcing it to return to its starting-point, and it is this shock of the repercussion of

our own affection which we call the others regard for ourselves, and which pleases us more

then than on its outward journey because we do not recognise it as having originated in

ourselves.

25

3

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

It is this mutual imbrication, where [o]rganization and members are

mutually constitutive, she attempts to illustrate. Empirically, she tries to

illustrate this through a self-confessional, and somewhat detailed account,

of how an interview might unfold. Theoretically, she turns to Lacans

Freudian/Hegelian meditations on the mirror stage, on Nachtrglichkeit (or

deferred action) and on identification (2007, p.1765).

Combining these (randomly?) selected theoretical notions from Lacan with

empirical observations from the interview, Harding makes the following

statement:

What a Lacanian approach suggests is something different: what we

were talking about [in the interview] was organizations which were in

us at the same time as we were in them (2007, p.1770).

There is no doubt that Lacans conception of the subject is decentred if

that is what is implied in the quote above. A number of Lacans famous

sayings testify to this: from Mans desire is the desire of the Other to I am

thinking where I am not, therefore I am where I am not thinking. More than

once, Lacan says that man is nothing but a signifier (1998, p.33), meaning

that the signifiers displacement determines subjects acts, destiny, refusals,

blindness, success, and fate, regardless of their innate gifts and instruction

(Lacan, 2006, p.21). In Hardings description, however, it is not quite clear

what the subject means. Nor is it clear at least not to my unimaginative

mind what it means to have an organization in us. In fact it leaves me

quite baffled, inescapably raising the image of a poor man who has eaten an

oversized angular object, like one of those snakes who in a fit of Napoleonic

hubris has swallowed a whole freaking hippo.

What I think Harding tries to explain, however, is that there is no such

thing as a predetermined, unambiguous, well-delineated, extra-discursive

self that is to say, a subject independently existing of any discursive

conditioning. And to this rather elementary argument that Lacan was

neither the first nor the last to make she adds that the subject assumes

different identities in different situations each of which comes with a set of

attributes. This, again, is not a very Lacanian argument. Still, in her attempt

to explain this flux of becoming-ness, Harding strenuously insists that

Lacan is of particular relevance. She says:

The influence of Hegels masterslave dialectic in Lacans work

facilitates exploration of the falling into each other of subject and

object, here the falling into each other of each other, and also of

organization and self, and of organization/self and organization/self.

26

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

Lacan, I will suggest, helps us understand something of the micromoments of organization/self making (2007, p.1764)

This might be linked to transference and counter-transference, or the

indistinguishable relation between the subject and the Other, where the

former is caught in the rails of metonymy (Lacan, 2006, p.431). However,

this would be too generous. Hardings words and ideas are marked by a

theoretical superficiality that is closer to Deepak Chopra than Lacan.

Another trait of Hardings writing, which clearly sets her apart from Lacan

and his discourse, is that she appeals to rather concrete or discrete

categories whenever speaking about the self or the subject. This becomes

painfully obvious as she describes the crowded room in which the

interview takes place:

There are thus at least seven parties in the interview the academic

self I myself generate, the academic me generated by the interviewee,

the managerial self generated by the interviewee, the interviewee

generated by the academic, the interviewee self generated by the

interviewee, and the two organizations, university and NHS Trust,

invoked as we offer questions and answers. Each brings with them

discourses of their professional selves generated or spoken through

numerous others all of whom will be invoking their organization as

they interact. The interview situation is thus a very crowded room.

(2007, p.1766)

Explaining the Lacanian subject as a set of discrete subjects (as seven

parties) invites confusion. The Lacanian subject is split true but it is not

split between a number of different selves (as the quote above would imply)

but internally split, crossed-out, constituted by an irreducible lack that

separates the subject not just from the object, but from itself.

In her experimentations with Lacan5 Harding falls short. While her

intention is undeniably good, she nonetheless ends up presenting an

obscured account of Lacan, reducing him to yet another postmodernist, or

theorist of becoming-ness.

Both Roberts and Harding draw directly on Lacan, with no

intermediary. This, however, is more an exception than a rule. It has become

extremely common, particularly in the field of management, to read Lacan

through Slavoj iek. This Slovene philosopher, also known as the giant

from Ljubljana, has successfully turned Lacan into a popular theorist. In

this regard, iek has made a tremendous achievement. But the new, lively

and refreshing Lacan ieks Lacan (painted in Hegelian colours) brings

5

The header of one of her sections is Experimenting with Lacan

27

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

some serious problems. If Lacan, in his own right, is susceptible to dubious

interpretations, then we can only begin to imagine the extent to which

ieks Lacan (no matter how lucid and ingenious it might be) is susceptible

to hasty, superficial, weird, and messed-up readings.

I wish it would have been more difficult to illustrate this intellectual

calamity but, unfortunately, a horrendous piece of work, from 2006, and

published in Human Relations, makes this illustration too simple. The

authors Katarzyna Kosmala and Olivier Herrbach manage to present an

account on jouissance so exceptionally poor that they dont even attribute

the concept to its proper inventor, Lacan, but instead to iek: Zizeks

notion of jouissance (2006, p.1399). Just for the record let us be clear that

iek does not in any way suggest that jouissance would be a concept of his

own invention, which a cursory glance at the index of The Sublime Object of

Ideology, (which Kosmala and Herrbach refer to 19 times) would quickly

reveal. It reads: jouissance, Lacanian concept of (1989, p.237).

However, the problems do not end here, but go on and on in a

stupendous fashion, until they reach farcical heights. When they begin by

defining jouissance as the paradoxical enjoyment that is characteristic of

the post-modern condition (2006, p.1394) there is still some hope after

all, jouissance is paradoxical. But instead of actually teasing out these

paradoxes, revealing for example how jouissance is a rather violent and

impossible category, assuming a number of different shapes, from its phallic

to feminine aspect and so on instead of saying anything about these

elementary aspects of jouissance they begin to speak of a mode of

jouissance, which they define as a playful mode that mediates boundaries

between social (here professional) and personal experience (2006, p.1423);

and this mode of jouissance, somehow, enables auditors to handle

organizational cynicism in the wider context of commercialization and the

post-modern condition, while at the same time articulating professional

ideology and displaying overall conformity to best practice (2006, p.1422).

Even though jouissance is one of these slippery concepts that have taken on

a number of different meanings over the years, it has never been conceived

of as a playful mode, let alone characteristic of the postmodern condition.

And the post-modern condition to which Kosmala and Herrbach

obsessively return comes with a weird description: they refer to it drawing

on iek?! as one in which reality becomes ideological (2006, p. 1394).

Anyone familiar with ieks works knows that these are not his words. The

outrageous quality of this article leaves me with only one question: is it a

fake a so-called Sokal hoax?

Fortunately the work of Kosmala and Herrbach is an exception.

Indeed, a number of ingenious and provocative accounts have been

produced over the last years. These works not only draw on Lacan and/or

28

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

iek in a solid and clever manner, but they also add new dimensions to

critical thinking about management. Though there are a number of works to

mention in this regard, I shall only describe two.

In their re-reading of Julian Orrs Talking About Machines, Alessia

Contu and Hugh Willmott show how work-identities are always susceptible

to control. To this end they turn, not immediately to Lacan, but to a number

of Lacanian themes via the social theory of hegemony.

The plot of Orrs book, to make a very short summary, is how a

number of engineers articulate and assume a professional identity (as

heroes) which retains a distinct distance from management. This identity

seems to pose a threat to management in that it, at least not openly,

complys with the normative sets of rules. On the other hand, this distance

from management makes the engineers even more committed, even more

engaged in their work.

If the work of Harding, as well as Kosmala and Herrbach, remained at

a level of identification, stating the rather obvious fact that identities are

fluid, ambiguous, contingent, and all the rest, then Contu and Willmott go

one step further:

By addressing processes of identification at work as illustrated by

the technicians fantasies of heroism, and as discussed by deploying

categories of the social theory of hegemony we have sought to move

beyond an understanding of their practice as a play of identities and

multiple discursive constructions. (2006, p.1779)

Connecting identification not only with meaning, but also enjoyment, Contu

and Willmott point to some of the important insights that the crossfertilization of Lacan and social theory have generated (see particularly

iek, 1989; Stavrakakis, 2007). It shows how fantasy renders identities

more captivating and beautiful but also maintains a status quo, an

experience of stability and sustainability.

There is another psychoanalytic theme that comes to the surface in

Contu and Willmotts reading, and this theme is even more pertinent to the

study of control and ideology. Beginning with the paradoxical situation

where those that most vehemently resist management, also are those that

best comply with the overall organizational goal, they reveal how

transgression is fraudulent. This goes back to the dual command of the

superego: the subject is not just compelled to follow the Law, but also to

transgress it in the right way. This means that periodic transgressions

might be inherent to social orders and normative ideals.

The last work in the series of the new management Lacanians I shall

comment on is Campbell Jones and Andr Spicers The Sublime Object of

29

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

Entrepreneurship, which seriously calls into question the commonly held

belief that behind the screen of the entrepreneur lurks a real, consistent,

entrepreneur:

Enlisting the work of Jacques Lacan and Slavoj iek, we attempt to

explain the continuing failure of entrepreneurship discourse to assign

the character of the entrepreneur a positive identity (2005, p.223)

Departing from their detailed, ambitious and well-researched literature

review they go on to argue that even though critical accounts have been

around for some time and even though psychoanalytic studies have

occasionally seeped into management journals they remain largely

disconnected. Lacan, they argue, has been almost totally sidestepped in

debates over postmodernism and organization (2005, p.228).

Turning particularly to Lacans notion of the real, Jones and Spicer

focus their attention not just on how the subject but the symbolic order as

such is plagued by a lack. This argument is central to ieks early work. In

a heavily cited passage, which also Jones and Spicer include in their work,

iek writes:

Today, it is a commonplace that the Lacanian subject is divided,

crossed-out, identical to a lack in the signifying chain. However, the

most radical dimension of Lacanian theory lies not in recognizing this

fact but in realizing that the big Other, the symbolic order itself, is

also barr, crossed-out, by a fundamental impossibility, structured

around an impossible/traumatic kernel, around a central lack. (iek,

1989, p.122, as cited in Jones and Spicer, 2005, p.233)

The fact that the big Other is structured around an impossible kernel forms

the basis for Jones and Spicer argument that the entrepreneur is ultimately

impossible. This does not mean that there would be no entrepreneurs, but

rather that there are no essences to which all variations of the signifier

entrepreneur would correspond. Even if this lies close to the postmodern/post-structural argument according to which all identities are

caught in a play of signifiers, it differs insofar as the impossibility does not

simply designate that the search is in vain, but rather that the impossibility

is precisely that element which holds an identity together.

III

This paper has described the recent trend of combining management studies

with the work of Lacan. While some of these works are rather poor, both in

30

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

their understanding of Lacan and their critique of management practices,

there are indeed a number of impressive studies clearly exhibiting the

relevance of Lacan to management studies.

The fact that Lacan can add something to the critique of management,

however, does not necessarily mean that Lacan or Lacanian studies has

gained anything from having been employed by management scholars. One

could even claim that the way in which Lacan has been conceived in

management studies (that is, in oversimplified thumbnail summaries), has

entailed a number of false images of Lacan, which is destined to be

reproduced in other contexts. In this regard management studies have made

a disservice to Lacanian studies, reducing them to yet another variation of

postmodern theory, where the plurality of discourses and endless play with

signifiers reign. I would argue, however, that this is only half the story.

Management as a practice is vital not only to organizational life but, more

generally, of an all-encompassing ideology following from capitalist work

relations. To be sure, the latest innovation of corporate cultures reveals that

work relations are not reducible to overt and bureaucratic forms of control

(such as surveillance) but are much more profound and insidious, targeting

employees in a number of ways.

In relation to these forms of control, where organizational narratives

target employees on a fantasmatic level, Lacanian studies have much to

offer. The question that arises in this context is whether it is appropriate to

concentrate on only one aspect of Lacans work, say jouissance, and remove

that from its original context. Indeed, this is a contested issue. While some

might feel ill at ease with the uncontrollable diffusion of Lacanian

psychoanalysis, arguing that Lacan should remain within the confines of the

psychoanalytic practice, others argue that Lacans theories can easily travel

between boundaries.

These issues will probably appear in the context of management

studies rather soon. Many would claim that Lacan is important and useful

insofar as he might advance already existing studies in the field. Indeed, this

is a valid point. If the purpose is but making a relevant argument

concerning, say, social control at the work-place, then we might conclude

that a detailed account on Lacan is somewhat overambitious, if not

downright pointless. But accepting all theoretical interpretations, however

brief and superficial they might be, on the basis of serving a higher purpose,

is problematic to say the least. This is particularly problematic with novel

theoretical developments in that these works tend to become representative,

as portraying the true Lacan.

However, anyone with even the slightest familiarity with Lacan knows

that theres not one way to read Lacan. He went through more than one

phase, making sharp u-turns every now and then, even deliberately

31

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

claiming that his teaching must not be too easily understood. Famously, he

stated you are not obliged to understand my writings. If you dont

understand them, so much the better that will give you the opportunity to

explain them (Lacan, 1998, p.34). Moreover, it is not much of a secret that

Lacan, whenever he subjected a text to critical interpretation, went quite far,

stretching the limits of the text to such an extent that it would take on an

entirely new meaning. It is also reported, by his biographer Elisabeth

Roudinesco, that Lacan subscribed to Kojves approach to philosophy

according to which a text is only the history of its interpretation. Needless

to say, this does not mean that any interpretation will do, but rather that

each interpretation, particularly when it comes to Lacan, has to be as wellresearched and supported as individual and innovative.

There is a last concern I wish to raise. This concern emanates from

how Lacan may be picked up by the conservatives, that is, by communities

occupied with questions of motivation. These scholars hunt high and low for

theories that could better assist them in their struggle to find even more

insidious and effective forms of control. In fact, Lacanian insights might be

used as a clear and solid template for crafting out alluring ideologies at the

work-place. I may exaggerate a little, but I shall not be too surprised if the

Lacanian invasion of management theory will result in the best-seller: Know

Your Employees Perversities: New Recipes for Effective Human Resource

Management.

32

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

References

Alvesson, M. and Willmott, H. (1992). On the Idea of Emancipation in

Management and Organization Studies. Academy of Management Review,

17, 3: 432-465.

Jones, C. and Spicer, A. (2005) The Sublime Object of Entrepreneurship,

Organization, 12(2), pp. 223-246.

Contu, A. and Willmott, H. (2006) Studying Practice: Situating Talking

About Machines, Organization Studies, 27(12), pp. 1769-1782.

Fleming, P. (2009) Authenticity and the Cultural Politics of Work, Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Fournier, V. and Grey. C. (2000). At the Critical Moment: Conditions and

Prospects for Critical Management Studies. Human Relations, Vol. 53, No. 1,

7-32.

Harding, N (2007) Essai: On Lacan and the Becoming-ness

Organization/Selves. Organization Studies, Vol. 28, No. 11, 1761-1773

of

Kojeve, A. (1980) Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the

Phenomenology of Spirit: Cornell University Press

Kosmala, K. and Herrbach, O. (2006). The ambivalence of professional

identity: On cynicism and jouissance in audit firms, Human Relations, 59,

10, 1393-1428.

Lacan, J. (1991) The Seminar, Book I: Freuds Papers on Technique, 19531954, New York: W. W. Norton.

Lacan, J. (1998) The Seminar, Book XX: On Feminine Sexuality, The Limits of

Love and Knowledge. Encore, 1972-3, New York: W. W. Norton.

Lacan, J. (2006) crits, New York: W. W. Norton.

Proust, M. (2003) Within a Budding Grove, Chapter 1, Rendered into HTML

by Steve Thomas for The University of Adelaide Library Electronic Texts

Collection.

http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/p/proust/marcel/p96w/chapter1.html

Stavrakakis y. (2007) The Lacanian Left: Psychoanalysis, Theory, Politics.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

iek, S. (1989). Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso.

33

Cederstrm, C. (2009) Lacan Goes Business, Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 7,

pp. 16-32 http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp/7.htm

Biographic details:

Carl is a PhD student at the Institute of Economic Research, Lund

University. His research is focused on psychoanalysis, technology and

management.

Address for Correspondence:

Institute of Economic Research, Lund University, Box 7080, SE-220 07 Lund

34

Вам также может понравиться

- Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic PerspectiveОт EverandInvitation to Sociology: A Humanistic PerspectiveРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (50)

- (Richard L. Kirkham) Theories of Truth A CriticalДокумент408 страниц(Richard L. Kirkham) Theories of Truth A Criticaljaimegv1234100% (4)

- Bad Leadership and Walmart PDFДокумент18 страницBad Leadership and Walmart PDFPedro NunesОценок пока нет

- 1998 - Rom Harré The Singular Self An Introduction To The Psychology of PersonhoodДокумент195 страниц1998 - Rom Harré The Singular Self An Introduction To The Psychology of PersonhoodLavinia ElenaОценок пока нет

- Catherine WilsonДокумент16 страницCatherine WilsonKyle ScottОценок пока нет

- Controlling the Conductor: Power Dynamics and Theories for Arts LeadersОт EverandControlling the Conductor: Power Dynamics and Theories for Arts LeadersОценок пока нет

- Ruddick When NothingДокумент14 страницRuddick When NothingKayla MarshallОценок пока нет

- Honor 2102 FinalpaperДокумент9 страницHonor 2102 Finalpaperapi-251850506Оценок пока нет

- Patterns of DevelopmentДокумент8 страницPatterns of Developmentapi-349927558Оценок пока нет

- Norberg, 2005 Wolf, 2005: ReferencesДокумент3 страницыNorberg, 2005 Wolf, 2005: ReferencesOana RaduОценок пока нет

- Paul A. Baran - The Commitment of The IntellectualДокумент6 страницPaul A. Baran - The Commitment of The IntellectualAhmed RizkОценок пока нет

- Sage Publications, Inc. American Sociological AssociationДокумент3 страницыSage Publications, Inc. American Sociological AssociationUjang RuhiyatОценок пока нет

- Lacan On The Discourse of Capitalism Critical Prospects: Philosophy, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan UniversityДокумент18 страницLacan On The Discourse of Capitalism Critical Prospects: Philosophy, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan UniversityLuiz Felipe MonteiroОценок пока нет

- Developing Decision-Making Skills For BusinessДокумент244 страницыDeveloping Decision-Making Skills For Businesshutsup100% (1)

- The Evil Princes of Martin Place Review - Steve KatesДокумент3 страницыThe Evil Princes of Martin Place Review - Steve KatesLiberty AustraliaОценок пока нет

- Cultural Competence: A Guide to Organizational Culture for Leaders in the ArtsОт EverandCultural Competence: A Guide to Organizational Culture for Leaders in the ArtsОценок пока нет

- Deleuzian Politics A Roundtable DiscussionДокумент46 страницDeleuzian Politics A Roundtable DiscussionLuis SalasОценок пока нет

- Journal of Public and Nonprofit AffairsДокумент57 страницJournal of Public and Nonprofit AffairsmahadiОценок пока нет

- Beyond Positivism, Behaviorism, and Neoinstitutionalism in EconomicsОт EverandBeyond Positivism, Behaviorism, and Neoinstitutionalism in EconomicsОценок пока нет

- Capitalism in Crisis (Volume 1): What's gone wrong and how can we fix it?От EverandCapitalism in Crisis (Volume 1): What's gone wrong and how can we fix it?Оценок пока нет

- The Two Sociologies and the Distinction Between Description and TheoryДокумент20 страницThe Two Sociologies and the Distinction Between Description and TheoryPedro Cárcamo PetridisОценок пока нет

- Adam Smith and Modern SociologyДокумент107 страницAdam Smith and Modern Sociologymacariof1904Оценок пока нет

- The Research ProposalДокумент16 страницThe Research ProposalMitzi McFarlandОценок пока нет

- Editorial Introduction: Robin MackayДокумент8 страницEditorial Introduction: Robin MackayMike VittnerОценок пока нет

- Conflicting Perspective ThesisДокумент7 страницConflicting Perspective ThesisProfessionalPaperWritingServiceCanada100% (3)

- The Entrepreneurial PersonalityДокумент24 страницыThe Entrepreneurial PersonalitystalynceliОценок пока нет

- Yes, We Have Noticed The Skulls - Slate Star CodexДокумент199 страницYes, We Have Noticed The Skulls - Slate Star CodexSunshine FrankensteinОценок пока нет

- Role of Elites in Economic DevelopmentДокумент3 страницыRole of Elites in Economic DevelopmentShay WaxenОценок пока нет

- From Marx To Emotions ElsterДокумент13 страницFrom Marx To Emotions ElstercrisloseОценок пока нет

- Ethics beyond moral theoryДокумент29 страницEthics beyond moral theoryValerie SolanasОценок пока нет

- Zombie Marx and Modern EconomicsДокумент9 страницZombie Marx and Modern EconomicsLebiadkin KapОценок пока нет

- Character Sketch EssayДокумент4 страницыCharacter Sketch Essaymywofod1nud2100% (2)

- To Thine Own Self Be True: The Role of Authenticity and the Self in Arts LeadershipОт EverandTo Thine Own Self Be True: The Role of Authenticity and the Self in Arts LeadershipОценок пока нет

- Memetics ThesisДокумент6 страницMemetics ThesisHelpWithWritingAPaperSiouxFalls100% (2)

- The Economic Imperative: Leisure and Imagination in the 21st CenturyОт EverandThe Economic Imperative: Leisure and Imagination in the 21st CenturyОценок пока нет

- Opacity: What We Do Not SeeДокумент115 страницOpacity: What We Do Not SeeraymondnomyarОценок пока нет

- End of Capitalism As We Knew ItДокумент12 страницEnd of Capitalism As We Knew Itسارة حواسОценок пока нет

- The Role of Theory in IRДокумент13 страницThe Role of Theory in IRPratyush GuptaОценок пока нет

- Women and Status in PhilosophyДокумент3 страницыWomen and Status in PhilosophyBabette BabichОценок пока нет

- Rationality and its cultural influencesДокумент34 страницыRationality and its cultural influencesMaria Jose FigueroaОценок пока нет

- Book Review - The Organization ManДокумент11 страницBook Review - The Organization Manag rОценок пока нет

- BOOK REVIEWS CRITICAL SUMMARY OF PLANNED CHANGE TECHNOLOGIESДокумент2 страницыBOOK REVIEWS CRITICAL SUMMARY OF PLANNED CHANGE TECHNOLOGIESJosé DurandОценок пока нет

- Carlos Aureus Critical Theory As It IsДокумент209 страницCarlos Aureus Critical Theory As It IsZenilda CruzОценок пока нет

- Navigating The Philosophical Landscape Insights From Atlas Shrugged and Atomic Habits by Israel Y.K LubogoДокумент9 страницNavigating The Philosophical Landscape Insights From Atlas Shrugged and Atomic Habits by Israel Y.K LubogolubogoОценок пока нет

- Paul Sweezy, 1958. Power Elite or Ruling ClassДокумент13 страницPaul Sweezy, 1958. Power Elite or Ruling ClassRobins TorsalОценок пока нет

- Essay of ShakespeareДокумент8 страницEssay of Shakespeareezhj1fd2100% (1)

- Good Lead Ins For A Research PaperДокумент8 страницGood Lead Ins For A Research Papermqolulbkf100% (1)

- Download Economic Philosophies Liberalism Nationalism Socialism Do They Still Matter Alessandro Roselli full chapterДокумент67 страницDownload Economic Philosophies Liberalism Nationalism Socialism Do They Still Matter Alessandro Roselli full chapterjames.farnham174100% (2)

- Critical Theory BookДокумент210 страницCritical Theory BookJohn Toledo100% (2)

- Leadership Unhinged: Essays on the Ugly, the Bad, and the WeirdОт EverandLeadership Unhinged: Essays on the Ugly, the Bad, and the WeirdОценок пока нет

- (19392419 - Historical Reflections - Réflexions Historiques) Elites and Their RepresentationДокумент6 страниц(19392419 - Historical Reflections - Réflexions Historiques) Elites and Their RepresentationArchisha DainwalОценок пока нет

- Bettering Humanomics: A New, and Old, Approach to Economic ScienceОт EverandBettering Humanomics: A New, and Old, Approach to Economic ScienceОценок пока нет

- Review Essay: Working With CynicismДокумент5 страницReview Essay: Working With CynicismCarlos MonakosОценок пока нет

- Thesis Statement For SpartacusДокумент6 страницThesis Statement For Spartacuskvpyqegld100% (2)

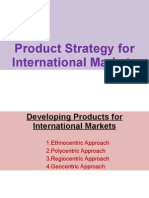

- Product Strategy For Interntional Markets-01.02Документ49 страницProduct Strategy For Interntional Markets-01.02anmol100% (4)

- MktintlДокумент1 страницаMktintlmaricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- Ull Text 01Документ220 страницUll Text 01maricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- Recovered File 1Документ8 страницRecovered File 1maricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- The KidДокумент1 страницаThe Kidmaricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- Shepard LostДокумент1 страницаShepard Lostmaricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- Asdfxz XCV 456 FDG Iyu J 2 5 FGДокумент1 страницаAsdfxz XCV 456 FDG Iyu J 2 5 FGmaricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- Sdflhads Asdf 435 FG 4432 Dog 4 e FG FGF FGGGG XVV 3t2345 FDSGFDG sdfbsfdg243Документ1 страницаSdflhads Asdf 435 FG 4432 Dog 4 e FG FGF FGGGG XVV 3t2345 FDSGFDG sdfbsfdg243maricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- MktintlДокумент1 страницаMktintlmaricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- ByДокумент18 страницBymaricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- Manual Profesional PlantillaДокумент10 страницManual Profesional Plantillamaricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- ExamacroДокумент10 страницExamacromaricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- Sample APA-Style PaperДокумент10 страницSample APA-Style PaperJeff Pratt100% (14)

- Food Packaging: © Food - A Fact of Life 2012Документ21 страницаFood Packaging: © Food - A Fact of Life 2012maricela_clasesОценок пока нет

- Mini Ice Plant Design GuideДокумент4 страницыMini Ice Plant Design GuideDidy RobotIncorporatedОценок пока нет

- Logistic Regression to Predict Airline Customer Satisfaction (LRCSДокумент20 страницLogistic Regression to Predict Airline Customer Satisfaction (LRCSJenishОценок пока нет

- Erp and Mis Project - Thanks To PsoДокумент31 страницаErp and Mis Project - Thanks To PsoAkbar Syed100% (1)

- EFM2e, CH 03, SlidesДокумент36 страницEFM2e, CH 03, SlidesEricLiangtoОценок пока нет

- Craft's Folder StructureДокумент2 страницыCraft's Folder StructureWowОценок пока нет

- Discretionary Lending Power Updated Sep 2012Документ28 страницDiscretionary Lending Power Updated Sep 2012akranjan888Оценок пока нет

- "60 Tips On Object Oriented Programming" BrochureДокумент1 страница"60 Tips On Object Oriented Programming" BrochuresgganeshОценок пока нет

- Death Without A SuccessorДокумент2 страницыDeath Without A Successorilmanman16Оценок пока нет

- KSRTC BokingДокумент2 страницыKSRTC BokingyogeshОценок пока нет

- Improvements To Increase The Efficiency of The Alphazero Algorithm: A Case Study in The Game 'Connect 4'Документ9 страницImprovements To Increase The Efficiency of The Alphazero Algorithm: A Case Study in The Game 'Connect 4'Lam Mai NgocОценок пока нет

- SAP ORC Opportunities PDFДокумент1 страницаSAP ORC Opportunities PDFdevil_3565Оценок пока нет

- Gary Mole and Glacial Energy FraudДокумент18 страницGary Mole and Glacial Energy Fraudskyy22990% (1)

- Chapter 3: Elements of Demand and SupplyДокумент19 страницChapter 3: Elements of Demand and SupplySerrano EUОценок пока нет

- Yi-Lai Berhad - COMPANY PROFILE - ProjectДокумент4 страницыYi-Lai Berhad - COMPANY PROFILE - ProjectTerry ChongОценок пока нет

- CFEExam Prep CourseДокумент28 страницCFEExam Prep CourseM50% (4)

- Q&A Session on Obligations and ContractsДокумент15 страницQ&A Session on Obligations and ContractsAnselmo Rodiel IVОценок пока нет

- Piping ForemanДокумент3 страницыPiping ForemanManoj MissileОценок пока нет

- Entrepreneurship Style - MakerДокумент1 страницаEntrepreneurship Style - Makerhemanthreddy33% (3)

- Impact of Coronavirus On Livelihoods of RMG Workers in Urban DhakaДокумент11 страницImpact of Coronavirus On Livelihoods of RMG Workers in Urban Dhakaanon_4822610110% (1)

- Part E EvaluationДокумент9 страницPart E EvaluationManny VasquezОценок пока нет

- Gattu Madhuri's Resume for ECE GraduateДокумент4 страницыGattu Madhuri's Resume for ECE Graduatedeepakk_alpineОценок пока нет

- Fundamental of Investment Unit 5Документ8 страницFundamental of Investment Unit 5commers bengali ajОценок пока нет

- Internship Report Recruitment & Performance Appraisal of Rancon Motorbikes LTD, Suzuki Bangladesh BUS 400Документ59 страницInternship Report Recruitment & Performance Appraisal of Rancon Motorbikes LTD, Suzuki Bangladesh BUS 400Mohammad Shafaet JamilОценок пока нет

- ADSLADSLADSLДокумент83 страницыADSLADSLADSLKrishnan Unni GОценок пока нет

- MCDO of Diesel Shed, AndalДокумент12 страницMCDO of Diesel Shed, AndalUpendra ChoudharyОценок пока нет

- Fujitsu Spoljni Multi Inverter Aoyg45lbt8 Za 8 Unutrasnjih Jedinica KatalogДокумент4 страницыFujitsu Spoljni Multi Inverter Aoyg45lbt8 Za 8 Unutrasnjih Jedinica KatalogSasa021gОценок пока нет

- Question Paper Code: 31364Документ3 страницыQuestion Paper Code: 31364vinovictory8571Оценок пока нет

- Jurisdiction On Criminal Cases and PrinciplesДокумент6 страницJurisdiction On Criminal Cases and PrinciplesJeffrey Garcia IlaganОценок пока нет

- ITSCM Mindmap v4Документ1 страницаITSCM Mindmap v4Paul James BirchallОценок пока нет

- 01 Automatic English To Braille TranslatorДокумент8 страниц01 Automatic English To Braille TranslatorShreejith NairОценок пока нет