Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Early Development Rottan Seat

Загружено:

Adi WardhanaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Early Development Rottan Seat

Загружено:

Adi WardhanaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

17

17

17

Key Word: Rattan, Chair Seat, Ming Dynasty

1. Background

From the mid-1660s, London saw the beginnings of

what was to be a boom in construction and trade of beech and

walnut chairs and armchairs made with weaved rattan seats and

back sections. Rattan is a family of vine-like plants, categorised

as species of palm, and harvested from tropical forests in East

and South-East Asia [1]. This natural product was imported from

these areas in increasing quantities from the mid-17th Century

onwards by the English East India Company. The fashion for

wooden chairs with weaved rattan seats and back sections

continued into the 18th Century, and drifted out of fashion as

chair manufacturers developed and embraced new designs and

forms. Today, many remaining examples of English 17th Century

rattan seated chairs survive in museums and private collections

throughout the UK.

2. Research Objectives

This study will address the initial introduction of rattan

in English chair construction. Previous scholarship has

predominantly studied the links between trading posts in India

and their influence on the stylistic design of early English rattan

chairs; particularly in relation to ethnic motifs represented on

chair back panels and front stretchers. However, while passing

reference has been made to possible structural links with chairs

of, or in the style of, Ming Dynasty China (such as the curved

splat for instance) little systematic research has been made in this

area. This article sets out to elucidate any links between Ming

Dynasty Chinese furniture and the rattan seats of early English

chairs, in respect of their design and structure.

3. Research Methods

For the analysis of the structural development of

early English rattan chair seats, a general field survey of 17th

Century English rattan chairs and armchairs was made from four

collections in the UK: The Victoria and Albert Museum, The

Lady Lever Gallery, The Geffrye Museum and Temple Newsam

House. In order to provide data for comparison, a control survey

of non-rattan seated chairs was also conducted. This included

chairs of probable English origin constructed during the same

period, 1650-1700.

4. Discussion and Analysis

4.1 Chinese Ming Dynasty Rattan Seating

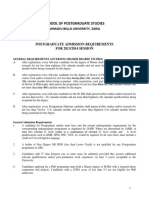

Two predominant weaving styles that were in evidence

during the Ming Dynasty, and are still employed today, were

examined [2]. The most common type of rattan weaving, often

seen on Ming and early Qing Dynasty armchairs and stools, was

of closely woven cane or bamboo. The alternative weaving style

that is often seen on larger pieces of furniture, and thus spread

over larger areas such as Chinese couches, was the sole type

integrated into the European chairs during the 17th Century. This

style, called hujiaoyan (), incorporates widely-spaced,

clearly defined octagonal apertures, a technique apparently

derived from bamboo weaving of a much earlier date [3], shown

in figure 1.

Fig. 1 Ming Dynasty couch with hujiaoyan weaving

4.2

Seat Height

For the analysis of seat height development, a survey of

Chinese armchairs constructed during the Ming Dynasty was

made from collections in the Victoria and Albert Museum and

the Shanghai Museum. In terms of seat height, the mean average

of both round and square back armchairs came to around 51.3cm.

The standard deviation (SD) of the seat heights was calculated at

1.31cm. Given the conservative, refined nature of these types of

chairs, with strict guidelines that governed the dimensions of

their construction, it can be said with some degree of confidence

that a stylistic conformity ranging slightly above 50cm was in

place for Ming Dynasty non-folding armchairs of these types

(central curved splat and fixed square seat with arm rails) [4].

Fig. 2 Examples of chair types, 2-4

In regards to rattan seated chairs, type 2 armless chairs had

an average 45.8cm seat height, dropping to 40.64cm for the

armchair version. Type 3 early tall back chairs had an average

46.4cm height and later tall back chairs and armchairs averaged

at 46.2cm and 40.3cm respectively. The height of the armless

chairs over all types remained steady, with barely a centimetre

differential between the mean averages for all three armless types.

The same was true for both armchair types, with both averaging

around 40cm. It is here proposed that this higher-than-average

seat height of armless rattan chairs (averaging around 46cm)

might be attributed to the influence of Ming Dynasty style

Chinese chair seats, and their respective higher height of nearer

50cm.

4.3 Seat Construction

Fig. 3 (Left) Type 2 armless chair, 1670-90

(Right) Type 4 armless tall back chair, 1690-1710

According to the survey results, within individual chair

groups, seats seem to have been dealt with fairly uniformly.

While type 2 armless chairs have, predominantly, an even and

equal number of holes at the front and back (reflecting the square

nature of their seats), type 2 armchairs and type 3 early tall back

chairs show inconsistency in the ratio of front and rear holes.

Later tall back chairs display more conformity, with a reduction

of 2 holes at the back in all cases where a difference between

front and rear occurs. This is particularly the case with chairs

whose front legs do not protrude above the top of the seat frame,

but stand flush with the bottom of the frame.

Type 2 armless chairs had a mean average of 23 holes per

frame, against an average 50.5cm seat width (2.19cm/hole). Type

2 armchairs saw an average of 30.8 holes across a wider frame of

59.74cm (1.94cm/hole). A fairly steady increase in the ratio of

holes per frame is apparent towards to the end of the 17th century,

with type 3 tall back chairs showing a ratio of 1.78 holes/cm and

type 4 later tall back chairs and armchairs showing 1.28cm/hole

and 1.24cm/hole respectively. Gradually therefore, rattan seats

grew more angular over the course of the surveyed period,

moving away from the more square-like structure that resembled

Ming Dynasty armchairs (figure 3).

4.4 Seat Depth

In slight contrast to the width of surveyed chair seats, the

depth of seat (particularly in respect to the earliest types)

remained surprisingly uniform within its respective chair type.

Within the surveyed type 2 armless chairs, depths ranged from

38.9cm-41.5cm, from shallowest to deepest. Type 2 armchairs

have an average (mean) depth of 43 cm, and an even smaller SD

of 0.57cm. Early tall back models show the greatest uniformity

however, with an average depth of 37.1cm and a deviation of

0.28cm. Later tall back chairs and armchairs had an SD of

1.45cm and 3.01cm respectively. The SD across the entire

collection of 17th rattan remains small; but for one extraordinary

example in the form of an unusual type 4 armless chair, it would

be calculated at 2.42cm.

5. Conclusions

(1) The structural survey demonstrated that whilst hujiaoyan

weaving was a technique imported in its entirety from China, this

technique of rattan weaving was integrated and developed into

English cane chairs at a relatively quick pace. This is

demonstrated by the steady increase in frame holes over the

entire 40 year period given.

(2) The level of variation that corresponds to the average seat

height for armless rattan seated English chairs is small enough to

argue that these chairs were regularly conformed higher than the

average level (around 43cm) of English non-rattan armless seats

of the same period. It is proposed that this is a probable influence

of Chinese Ming Dynasty-style chairs.

(3) In regard to the development of early English rattan seats,

there is more standardisation than previously assumed when

looking at individual categories of chairs. Given that the

surveyed chairs were constructed in different workshops over

different periods, the small variance in terms of seat height and,

in particular, seat depth (an overall average standard deviation of

1.27cm) should be considered significant.

Notes and References

1) Dransfield J. and Manokaran N (Eds.). Plant Resources of

South-East Asia, No.6 Rattans. Pudoc Scientific Publishers:

Wageningen, 1993.

2) Wang, Z. Authentication of Ming and Qing Furniture.

Shanghai shu dian chu ban she, 2007; 131, 137.

3) Wang. S. Connoisseurship of Chinese Furniture, Ming and

Early Qing Dynasties [Vol.1]. Art Media Resources: Hong

Kong, 1990; 146

4) Ishimura, S. A Research on the Relation between Living

Culture and Chairs in the Chinese Countryside. Housing

Research Foundation Annual Report 2000; 27:88

Вам также может понравиться

- Gending Wanasaba AsriДокумент2 страницыGending Wanasaba AsriAdi WardhanaОценок пока нет

- Gendhing Pahargyan Manten2Документ16 страницGendhing Pahargyan Manten2Adi WardhanaОценок пока нет

- Gambir SawitДокумент3 страницыGambir SawitAdi WardhanaОценок пока нет

- Gendhing Pahargyan MantenДокумент6 страницGendhing Pahargyan MantenAdi WardhanaОценок пока нет

- Eling-Eling SuralayaДокумент1 страницаEling-Eling SuralayaAdi WardhanaОценок пока нет

- Clunthang-Pelog BRДокумент2 страницыClunthang-Pelog BRAdi WardhanaОценок пока нет

- Eling-Eling KasmaranДокумент1 страницаEling-Eling KasmaranAdi WardhanaОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Rizal's Ancestors Have Been Famous Since The Beginning of His Life. It Is Very Common For Them To AttendДокумент4 страницыRizal's Ancestors Have Been Famous Since The Beginning of His Life. It Is Very Common For Them To Attendfarhanah ImamОценок пока нет

- Repair FutsalДокумент4 страницыRepair FutsalAhmad Mustanir HadadakОценок пока нет

- مذكرة لغة انجليزية أولى ابتدائى ترم أول 2022 معدلةДокумент102 страницыمذكرة لغة انجليزية أولى ابتدائى ترم أول 2022 معدلةMohamed RaafatОценок пока нет

- Drum, Dance, Chant and SongДокумент12 страницDrum, Dance, Chant and Songrazvan123456Оценок пока нет

- The Best Man: Martin ShawДокумент3 страницыThe Best Man: Martin ShawRodrigo Garcia SanchezОценок пока нет

- Internship Report: Architecturalprofessional PracticeДокумент11 страницInternship Report: Architecturalprofessional PracticeShreesh Jagtap0% (1)

- Wood Design & BuildingДокумент48 страницWood Design & BuildingFernando Mondragon100% (1)

- Perfect Color Palettes For YouДокумент1 страницаPerfect Color Palettes For YouamandaОценок пока нет

- Lembar Jawaban UAS B.InggrisДокумент4 страницыLembar Jawaban UAS B.InggrisArya GiawaОценок пока нет

- From The Joe Madisia Biography Series IIДокумент16 страницFrom The Joe Madisia Biography Series IIVDОценок пока нет

- En Erco Architecture LightДокумент21 страницаEn Erco Architecture LightDjurdjica TerzićОценок пока нет

- Dholakiya Schools STD 10: SS Unit Test: Chapters: 1,2 Date: 27/11/21 Total Marks: 40 Time: 1:30Документ5 страницDholakiya Schools STD 10: SS Unit Test: Chapters: 1,2 Date: 27/11/21 Total Marks: 40 Time: 1:30Mihir JОценок пока нет

- Mbs99 AДокумент121 страницаMbs99 AMylène RacineОценок пока нет

- Jazz Piano Rep List 2016Документ36 страницJazz Piano Rep List 2016Emma0% (1)

- Godisnjak 48-7Документ295 страницGodisnjak 48-7varia5Оценок пока нет

- Green GNXДокумент2 страницыGreen GNXHai NguyenОценок пока нет

- Unit 3-Romantic PaintingДокумент48 страницUnit 3-Romantic PaintingGinaОценок пока нет

- So 2ND Ed Uin Read Extra U10 PDFДокумент2 страницыSo 2ND Ed Uin Read Extra U10 PDFDavid Roy JagroskiОценок пока нет

- Schubert Franz Peter Serenade Le Chant Du Cygne IV 27054Документ4 страницыSchubert Franz Peter Serenade Le Chant Du Cygne IV 27054WILAME ACОценок пока нет

- Bach Magnificat in DДокумент3 страницыBach Magnificat in DYingbo Shi100% (1)

- Carmen Suite - G. Bizet - For String Quartet-Violín 1Документ3 страницыCarmen Suite - G. Bizet - For String Quartet-Violín 1Juan sebastian CantorОценок пока нет

- Gullickson's Glen by Daniel SeurerДокумент15 страницGullickson's Glen by Daniel SeurerasdaccОценок пока нет

- Remi Butler - 2020 - 1Документ2 страницыRemi Butler - 2020 - 1Remi ButlerОценок пока нет

- Ahmadu Bello University Postgraduate Admission RequirementsДокумент36 страницAhmadu Bello University Postgraduate Admission Requirementsbashir isahОценок пока нет

- Polish Folk Art Cutouts: DesignДокумент3 страницыPolish Folk Art Cutouts: DesignCorcaci April-DianaОценок пока нет

- Deus Ex Machina A Choreo-Cinematographic PDFДокумент10 страницDeus Ex Machina A Choreo-Cinematographic PDFMine DemiralОценок пока нет

- Early MusicДокумент10 страницEarly MusicEsteban RajmilchukОценок пока нет

- Titanic ShipДокумент35 страницTitanic ShipМаксим ШульгаОценок пока нет

- William Carlos Williams' Modernist PoetryДокумент2 страницыWilliam Carlos Williams' Modernist PoetryPaula 23Оценок пока нет

- Fairbairn Defendu PDFДокумент2 страницыFairbairn Defendu PDFMacario0% (6)