Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Adicciones

Загружено:

fataldjАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Adicciones

Загружено:

fataldjАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

original

adicciones vol.27, issue1 2015

Smoking cessation after 12 months

with multi-component therapy

Abstinencia a los 12 meses de un programa

multicomponente para dejar de fumar

Antnia Raich*,**** ; Jose Maria Martnez-Snchez**,***; Emili Marquilles*; Ldia Rubio*;

Marcela Fu**; Esteve Fernndez**,****

*Unidad de Tabaquismo (Smoking Cessation Unit), Althaia Xarxa Assistencial Universitria de Manresa FP. **Unidad

de Control del Tabaquismo (Smoking Control Unit), Institut Catal dOncologia (Catalonian Institute of Cancer) (ICOIDIBELL). ***Unidad de Bioestadstica (Biostatistics Unit), Departamento de Ciencias Bsicas (Dept. of Basic Sciences),

Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Sant Cugat del Valls. ****Departamento de Ciencias Clnicas (Dept. of Clinical

Sciences), Campus de Bellvitge, Facultat de Medicina, Universitat de Barcelona.

Abstract

Resumen

Smoking is one of the most important causes of morbidity and

El tabaquismo es una de las causas de morbimortalidad ms

mortality in developed countries. One of the priorities of public health

importantes en los pases desarrollados. Uno de los objetivos

programmes is the reduction of its prevalence, which would involve

prioritarios de los programas de salud pblica es la disminucin de su

millions of people quitting smoking, but cessation programs often

prevalencia lo que implica que millones de personas dejen de fumar,

have modest results, especially within certain population groups. The

sin embargo los programas de cesacin a menudo tienen resultados

aim of this study was to analyze the variables determining the success

discretos, especialmente con algunos grupos de poblacin. El objetivo

of a multicomponent therapy programme for smoking cessation. We

de este estudio fue analizar la eficacia de un tratamiento de cesacin

conducted the study in the Smoking Addiction Unit at the Hospital

tabquica multicomponente realizado en una unidad de tabaquismo

of Manresa, with 314 patients (91.4% of whom had medium or

hospitalaria. Fue realizado en la Unidad de Tabaquismo del Hospital

high-level dependency). We observed that higher educational level,

de Manresa, e incluy 314 pacientes (91,4% presentaban un nivel de

not living with a smoker, following a multimodal programme for

dependencia medio o alto). Se observ que el nivel de estudios, no

smoking cessation with psychological therapy, and pharmacological

convivir con fumadores, seguir la terapia multicomponente y utilizar

treatment are relevant factors for quitting smoking. Abstinence

tratamiento farmacolgico son factores relevantes en el xito al dejar

rates are not associated with other factors, such as sex, age, smoking

de fumar. La tasa de abstinencia no se asocia con otras caractersticas

behaviour characteristics or psychiatric history. The combination of

como el sexo, la edad, las caractersticas del hbito tabquico o el

pharmacological and psychological treatment increased success rates

presentar antecedentes psiquitricos. La combinacin del tratamiento

in multicomponent therapy. Psychological therapy only also obtained

farmacolgico y psicolgico aument las tasas de xito en la terapia

positive results, though somewhat more modest.

multicomponente. La terapia psicolgica nica tambin obtuvo

Key words: multimodal treatment, smoking cessation, mental disorders,

resultados positivos aunque ms modestos.

heavy smokers.

Palabras clave: tratamiento multicomponente, deshabituacin tab

quica, trastornos mentales, pacientes con alta dependencia.

Received: June 2014; Accepted: October 2014

Address for correspondence:

Antnia Raich. Unidad de Tabaquismo. Althaia Xarxa Assistencial Universitria de Manresa FP. C/Dr. Llatjs, 6-8, edifici CSAM. 08243

Manresa. E-mail: araich@althaia.cat

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1 PAGES 37-46

37

Smoking cessation after 12 months with multi-component therapy

Method

mong the most challenging aspects involved in

interventions with smokers are the chronicity of

this addiction and the apparent limitations of

programmes designed to help people quit smoking. In order to design interventions with maximal levels of

efficiency, it is of the utmost importance to consider previous

studies that can contribute data for analyzing the conditions

and characteristics of efficacious treatments, the predictors

of good results, the characteristics of participants and their

success or failure in smoking cessation programmes.

There are a range of different types of smoking cessation

interventions: brief advice from a health professional (the

person is advised and encouraged to give up smoking), self-help

courses and materials, the prescription of pharmacological

treatments with or without follow-up, motivational

interventions, and multicomponent therapy (Hays, Ebbert, &

Sood 2009; Hays, Leischow, Lawrence, & Lee 2010; Stead &

Lancaster 2012). The last in this list may be the most intensive

of such interventions, since it combines psychological and

pharmacological interventions of proven efficacy. The results

of smoking cessation treatments currently available are modest:

the most efficacious have achieved no more than 30-40%

abstinence rates at the one-year follow-up (Ranney, Melvin,

Lux, McClain, & Lohr, 2006) in general population.

Pharmacological treatment and smoking cessation advice

have been widely analyzed in the scientific literature, and the

majority of studies concur that they increase the likelihood

of success in quitting smoking (PHS Guideline Update

Panel, Liaisons, and Staff, 2008; Silagy, Lancaster, Stead,

Mant, & Fowler, 2004; Wilkes, 2008). Various studies have

shown that sociodemographic variables (sex, educational

level, socioeconomic level) influence the results, as well

as the characteristics of the smoking addiction and the

persons health antecedents (Nerin, Novella, Beamonte,

Gargallo, Jimenez-Muro, & Marqueta, 2007; Ramon &

Bruguera, 2009). However, there is scarcely any research

analyzing these aspects in multicomponent therapy, whose

efficacy has indeed been studied, but not the influence on it

of these variables (Bauld, Bell, McCullough, Richardson, &

Greaves, 2010; Hays et al., 2009).

Addictive disorders are complex entities that affect

human behaviour with physiological, psychological and

sociological bases. The comprehensive approach involved

in multicomponent therapy is that which has yielded

the best outcomes in the medium and long term (PHS

Guideline Update Panel, 2008; Alonso-Perez, AlonsoCardeoso, Garcia-Gonzalez, Fraile-Cobos, Lobo-Llorente,

& Secades-Villa, 2013; Stead & Lancaster 2005). Thus, the

aim of the present study was to analyze the efficacy of a

multicomponent smoking cessation treatment carried out

in a hospital Smoking Addiction Unit and how its outcomes

were influenced by the characteristics of participants and

their addiction, social factors, different pharmacological

treatments, and psychological therapy.

Design and participants

Longitudinal study of 314 patients who attended the

Smoking Addiction Unit at the Hospital de Manresa

(Manresa, Spain) to try and quite smoking between January

2001 and December 2009. This unit takes in patients

referred from other departments in the same hospital

or from primary care services, where all have received

brief interventions for smoking cessation, and more than

65% have received specific interventions that have failed

(carried out by specialist nurses working in primary care,

cardiology units, pulmonary units, etc.). Included in the

study were all those patients treated in the unit that followed

multicomponent therapy; inclusion was in accordance

with order of registration on the waiting list, where they

remained for an average of nine months. Exclusion criteria

for the multicomponent treatment were: psychiatric illness

in an acute phase or a psychotic disorder, reading and/or

writing problems, and other disorders that would make it

difficult to follow the therapy. The majority of the patients

referred to this programme were from the central area of

Catalonia (Manresa and the surrounding area).

Procedure

A one-year follow-up was carried out, counting from the

point at which the patient gave up or should have given

up smoking, which for the patients meant a mean of 14

months of therapy. A total of 90% of the patients received

the multicomponent therapy in group format, while just

10% did so on an individual basis. The structure of the

therapy was the same for the group and individual formats.

In principle, all patients were assigned to the group mode,

the individual format being employed only in exceptional

cases (pregnant patients who could not wait for the start of

group programme, or people with difficulties for following

the group timetable). The therapy was implemented by the

same professionals (a psychologist and a lung specialist)

throughout the study. The multicomponent treatment

programme brings together all those strategies that have

shown themselves to be efficacious (Alonso-Perez et al.,

2014; Fiore, Jaen, Baker, Bailey, Benowitz, & Curri, 2009):

psychological treatments based on behavioural, cognitive,

motivational and relapse prevention techniques combined

with pharmacological treatment based on nicotine

replacement (Becoa & Mguez, 2008; Ranney et al.,

2006), bupropion and varenicline (Wu, Wilson, Dimoulas,

& Mills, 2006; Tinich & Sadler 2007; Cahill, Stevens, &

Lancaster 2014). Multicomponent therapy consists of three

phases: a) preparation, which involves psychoeducation

about addiction, motivation to quit, changing habits,

and monitoring of tobacco use with or without reduction

in six weekly 75-minte sessions; b) cessation, in which

pharmacological treatment is introduced where applicable

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1

38

Antnia Raich, Jose Maria Martnez-Snchez, Emili Marquilles, Ldia Rubio, Marcela Fu and Esteve Fernndez

in person at the hospital or by telephone for the follow-up

(months 1, 3, 6 and 12) and all the relevant information

recorded. All the patients who claimed to remain abstinent

were given an appointment to take a carbon monoxide test.

and the therapists work on coping with the day the patient

gives up (D-Day), withdrawal syndrome and craving,

in four two-weekly 60-minute sessions; and c) relapse

prevention, following the models of Marlatt, Curry and

Gordon (1988) and Baer and Marlatt (1991), in 10 monthly

60-minute sessions.

The therapy involved no direct financial cost for the

patients, except for the pharmacological treatment, for

which they had to pay. All the patients received the same

psychological therapy and assignment to one type of

pharmacological treatment or another was in line with

clinical criteria, taking into account at each moment the

treatment that could most benefit the patient in accordance

with availability, previous experience, personal health

antecedents and pharmacological interactions with other

treatments he or she might be undergoing at that time.

Some patients decided not to take up the treatment, and

this group also includes those who did not receive treatment

because they dropped out of the programme before

beginning it (n=69).

Those patients that did not take up the treatment for

whatever reason remained in the study, and were contacted

by telephone or personally for the purpose of obtaining the

necessary follow-up data. The distribution of the patients

across the different treatment modes and retention up to

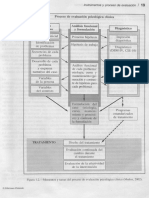

the 12-month follow-up are shown in detail in Figure 1.

Information on sociodemographic variables, heath

antecedents and smoking characteristics were obtained at

the first visit (which was always individual) based on the

patient interview and the data from the persons clinical

records. Information on how the patient was developing

and the drugs used was recorded in the first, third, sixth and

twelfth month after D-Day. All patients were contacted

Instruments

The objective measure of abstinence used was level of

carbon monoxide (CO) in expired air, or co-oximetry

(abstinent if CO6ppm) (Middleton & Morice, 2000). The

instrument employed for this purpose was a co-oximeter

(Bedfont Pico Smokerlyzer).

For the data analysis, the following variables were taken

into account: sex, age, educational level, living with other

smokers or not, occupation, number of cigarettes smoked

per day, years smoked, level of dependence according to

Fagerstrm Test (low dependence 4; medium=5; high 6),

psychiatric antecedents (yes/no), multicomponent therapy

(yes/no), pharmacological treatment (yes/no), and drug

used for smoking cessation.

Statistical analysis

The categorical variables are shown as absolute value

and relative frequency. The continuous variables are shown

with the mean and standard deviation. We calculated the

accumulated incidence of abstinence, both global and

according to multicomponent programme, at 1, 3, 6 and

12 months, together with its 95% confidence interval. The

variables associated with relapse at 12 months were examined

using bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models.

In the multivariate logistic regression model we introduced

the covariables found to be significant in the bivariate

analysis, or with evidence of their association. We used a

stepwise exclusion strategy controlled by the researcher. The

Baseline visit

N=314

Dropped out before starting programme

N=69

Multicomponent programme

N=245

Psychological treatment

N=81

Abstinent

N=1

Not abstinent

N=68

Abstinent

N=13

Not abstinent

N=68

Figure 1. Patient flow

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1

39

Psychological and pharmacological

treatment

N=164

Abstinent

N=61

Not abstinent

N=103

Smoking cessation after 12 months with multi-component therapy

received psychological therapy only, with a rate of 16%, and

those who received no type of treatment (1.4%) (Table 2).

In the bivariate analysis, sex, age, years smoked,

dependence (score on Fagerstrm Test) and psychiatric

antecedents, did not appear as relapse risk factors. A trend

towards significance was observed, with higher relapse rate,

among younger patients (OR 0.98) and those who had

been smoking for 20 years or less (OR 1.96). Having at least

raw and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and the 95% confidence

intervals (CI 95%) were calculated. Statistical significance

level was bilateral 5% (p<0.05).

The programs used in the statistical analysis were IBM

SPSS Statistics for Windows v.22 (IBM Corporation,

Armonk, New York, USA) and Stata v.10 (StataCorp LP,

College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants (n=314)

Mean age of the patients was 48.5 years; 61.8% were men,

61.9% had only elementary education and 32.6% were skilled

workers or professionals. As regards smoking characteristics,

50.3% lived with other smokers, 34.4% had been smoking

for 35 years or more, 48.2% smoked 21 or more cigarettes

per day, and 68.8% had high nicotine dependence (score

6) according to the Fagerstrm Test. Furthermore, 57.1%

of the patients had made two or more previous attempts to

quit smoking, 85% had been referred to the programme

from other hospital departments where they were being

treated for illnesses associated with smoking, and 58% had

psychiatric antecedents (Table 1).

Of the total 314 patients, we included all those who during

the studied period put their names down on the waiting list

and came to the first appointment when called; of these, 69

dropped out of the programme before the first session of

multicomponent therapy and the remaining 245 began the

multicomponent therapy (Figure 1). Of these 245 patients,

81 did not receive the pharmacological treatment, on their

own or the doctors decision (n=29) or because they gave up

the therapy before completing the first phase (n=52).

Abstinence for the whole sample was 50.3% at the onemonth follow-up, 38.5% at three months, 29.0% at six

months and 23.9% at 12 months. Patients who received

psychological and pharmacological treatment obtained the

highest abstinence rates at all the follow-up points, showing an

abstinence rate at 12 months of 37.2%, followed by those who

n=(%)

Mean age [standard deviation]

48,5[12,1]

Sex

Man

Woman

194 (61,8)

120 (38,2)

Educational level

Primary

Secondary

University

192 (61,9)

63 (20,3)

55 (17,7)

Living with smokers

No

Yes

156 (49,7)

158 (50,3)

Years smoked

20

21-35

> 35

68 (21,7)

138 (43,9)

108 (34,4)

Fagerstrm Test

< 4 Low

4-5 Medium

6 High

27 (8,6)

71 (22,6)

216 (68,8)

Psychiatric antecedents

No

Yes

132 (42,0)

182 (58,0)

Multicomponent programme

Neither psychological nor pharmacological

treatment

Psychological treatment

Psychological and pharmacological treatment

69 (22,0)

81 (25,8)

164 (52,2)

Nicotine replacement therapy

Bupropion

Varenicline

84 (51,2)

30 (18,3)

50 (30,5)

Table 2.

Abstinence (global and according to multicomponent programme) at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months

n

1 montha

3 monthsa

6 monthsa

12 monthsa

314

50,3 (44,6-56,0)

38,5 (33,1-44,2)

29,0 (24,0-34,3)

23,9 (19,3-29,0)

Neither psychological nor pharmacological treatment

69

2,9 (0,4-10,1)

1,4 (0,04 -7,8)

1,4 (0,04 -7,8)

1,4 (0,04 -7,8)

Psychological treatment

81

27,2 (17,9-38,2)

23,5 (14,8-24,2)

16,0 (8,8-25,9)

16,0 (8,8-25,9)

Psychological and pharmacological treatment

164

81,7 (74,9-87,3)

61,6 (53,7-69,1)

47,0 (39,1-54,9)

37,2 (29,8-45,1)

Nicotine replacement therapy

84

83,3 (73,6-90,6)

61,9 (50,7-72,3)

50,0 (38,9-61,1)

44,0 (33,2-55,3)

Bupropion

30

83,3 (65,3-94,4)

70,0 (50,6-85,3)

50,0 (31,3-68,7)

36,7 (19,9-53,9)

Varenicline

50

78,0 (64,0-88,5)

56,0 (41,3-70,0)

40,0 (26,4-54,8)

26,0 (14,6-40,3)

Global

According to multicomponent programme

% (95% Confidence Interval)

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1

40

Antnia Raich, Jose Maria Martnez-Snchez, Emili Marquilles, Ldia Rubio, Marcela Fu and Esteve Fernndez

Table 3.

Risk factors for relapse at 12 months. Bivariate analysis.

Abstinencea

n=75

Relapsesa

n=239

Raw OR (95% CI)

p value

50,7[12,0]

47,8[12,0]

0,98 (0,96-1,00)

0,068

Sex

Man

Woman

51 (26,3)

24 (20,0)

143 (73,7)

96 (80,0)

1b

1,43 (0,82-2,47)

0,205

Educational level

Primary

Secondary

University

35 (18,2)

23 (36,5)

16 (29,1)

157 (81,8)

40 (63,5)

39 (70,9)

1b

0,39 (0,21-0,73)

0,54 (0,27-1,08)

0,003

0,082

Living with smokers

No

Yes

47 (30,1)

28 (17,7)

109 (69,9)

130 (82,3)

1b

2,00 (1,18-3,41)

0,011

Years smoked

> 35

21-35

<= 20

32 (29,6)

31 (22,5)

12 (17,6)

76 (70,4)

107 (77,5)

56 (82,4)

1b

1,45 (0,82-2,58)

1,96 (0,93-4,15)

0,202

0,077

Fagerstrm Test

<4 Low

4-5 Medium

<= 6 High

7 (25,9)

24 (33,8)

44 (20,4)

20 (74,1)

47 (66,2)

172 (79,6)

1b

0,68 (0,25-1,85)

1,37 (0,54-3,44)

0,455

0,505

Psychiatric antecedents

No

Yes

36 (27,3)

39 (21,4)

96 (72,7)

143 (78,6)

1b

1,38 (0,82-2,32)

0,231

1 (1,4)

13 (16,0)

61 (37,2)

68 (98,6)

68 (84,0)

103 (62,8)

1b

0,08 (0,01-0,60)

0,02 (0,003-0,18)

0,015

< 0,001

37 (44,0)

11 (36,7)

13 (26,0)

47 (56,0)

19 (63,3)

37 (74,0)

1b

1,36 (0,58-3,21)

2,24 (1,04-4,81)

0,483

0,039

Mean age [standard deviation]

Multicomponent programme

Neither psychological nor pharmacological

treatment

Psychological treatment

Psychological and pharmacological treatment

Nicotine replacement therapy

Bupropion

Varenicline

a

Number of individuals (% of row). b Reference category

OR: Odds Ratio; 95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval .

Table 4.

Risk factors for relapse at 12 months.

Multivariate analysis.

secondary education, not living with smokers, and receiving

multicomponent therapy with psychological treatment

alone or in conjunction with pharmacological treatment

emerged as predictors of success (p<0.05). As regards

pharmacological treatments, nicotine replacement therapy

is found to be the best predictor of success, with significant

differences compared to varenicline, though not compared

to bupropion (Table 3).

In the multivariate analysis, the factors found to protect

against relapse were having a secondary or university

education, not living with smokers, and receiving some type

of smoking cessation treatment, be it psychological only or

psychological plus pharmacological (Table 4).

Adjusted OR (95% CI)

p value

Age

0,98 (0,96-1,01)

0,169

Sex

Man

Woman

1a

1,36 (0,69-2,66)

0,371

Educational level

Primary

Secondary

University

1a

0,36 (0,18-0,73)

0,41 (0,19-0,89)

0,005

0,024

Living with smokers

No

Yes

1a

2,03 (1,12-3,68)

0,020

1a

0,06 (0,01-0,51)

0,010

0,02 (0,003-0,17)

<0,001

Multicomponent programme

Neither psychological nor

pharmacological treatment

Psychological treatment

Psychological and

pharmacological treatment

a

OR: Odds Ratio; 95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval.

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1

41

Smoking cessation after 12 months with multi-component therapy

Discussion

does not reduce the weight of this variable. In the univariate

analysis we observed that it is only significant to have

secondary education, and that having a university education

does not attain statistical significance, even though this aspect

does emerge as significant in the multivariate analysis. This is

probably due to the fact that in the subgroup with university

education there is a higher proportion of young people, in

whom we already saw a greater tendency for relapse; therefore,

when we adjust for age, having a university education also

shows up as significant. Thus, educational level is significant

as a predictor of success in multicomponent therapy. Bearing

in mind that various studies have shown how people with

higher levels of education respond better to psychological

therapy of whatever kind (Haustein, 2004; Piper et al., 2010;

Siahpush, McNeill, Borland, & Fong, 2006), all of this would

be in support of the hypothesis that psychological aspects play

a relevant role in attempts to quit smoking (Likura, 2010).

Occupational or professional level was also analyzed,

though it only yielded significant differences in the first

and sixth months, and not at the 12-month follow-up.

Educational level is stable in adults, while the occupation

variable can show considerable instability over the course

of life (Belleudi et al., 2006), which would explain why the

former yields greater significance and more robust results

than the latter, as the previously-cited studies have also

shown (Fernndez et al., 2006; Yanez, Leiva, Gorreto, Estela,

Tejera, & Torrent, 2013).

Level of dependence presented differences in the results,

as observed in previous studies (Baer & Marlatt, 1991;

Fernndez et al., 1998), though these differences were only

significant at the one-month and three-month follow-ups.

This is probably due to the effect of the pharmacological

treatment. The Fagerstrm Test is a good indicator of the

smokers level of physical dependence, but it is not reliable

for measuring psychological dependence (Nern et al.,

2007). People with high levels of physical dependence are

those that most benefit from pharmacological treatment

(De Leon, Diaz, Bevona, Gurpegui, Jurado, GonzalezPinto, 2003). However, in the medium and long term after

the pharmacological treatment is finished, what could be

determining relapse is not so much the physical dependence

level as the degree of psychological dependence and

the capacity for developing relapse prevention strategies

(Hajek, Stead, West, Jarvis, Hartmann-Boyce, & Lancaster,

2013; Siahpush et al., 2006).

The majority of studies to date with psychiatric patients

(Killen et al., 2008) have found them to have more difficulty

giving up smoking and to present higher relapse rates. In

our study, however, no such differences were appreciated.

Various factors could explain this: first of all, the broad

concept of psychiatric antecedents we employed, considering

a patient to fall into this category if they had at any time in

their life received a psychiatric diagnosis and been treated,

and this covers a wide range of levels of severity. Secondly,

As a result of a multicomponent smoking cessation

programme, 1 in 4 smokers with high levels of dependence

remained abstinent at the 12-month follow-up. These results

are independent of sex, age, psychiatric antecedents or

smoker characteristics. On the other hand, social factors

such as educational level or living/not living with other

smokers did indeed influence the results of this type of

therapy. Furthermore, receiving multicomponent therapy

with or without pharmacological treatment clearly increases

the likelihood of success, though patients who also receive

pharmacological treatment achieve better abstinence rates.

The results obtained in this study raise a number of points

for discussion. Some of the findings are at odds with those of

previous research. Thus, for example, the abstinence rates

are somewhat lower than might be expected for a highintensity therapy, while aspects such as participants sex or

psychiatric antecedents, which in the majority of studies

affect the success of the treatment (Fernndez, Garca,

Schiaffino, Borrs, Nebot, & Segura, 2001; Nern et al.,

2007; Perkins & Scott, 2008; Piper et al., 2010) do not yield

differences in this respect in our study.

These low abstinence rates compared to those of other

studies (Becoa & Vazquez, 1998; Nern et al., 2007) may

be due to the fact that the sample is not from the general

population; indeed, it is highly selective: the study took place

in a hospital smoking cessation unit, with participants who

had failed in previous attempts to quit smoking, with high

levels of nicotine dependence and who had been referred

from other hospital departments because they presented

smoking addiction-related pathologies. Some authors refer

to such people as recalcitrant smokers (Wilson, Wakefield,

Owen, & Roberts, 1992). Moreover, the results were analyzed

on an intent-to-treat basis, which makes it difficult to

compare this study with previous ones that exclude those

patients who gave up after the first visit. We found no

differences between men and women at any of the followups or at the end of the treatment. Although some previous

studies refer to sex differences (Bjornson et al., 1995) in

success rates for smoking cessation, more recent studies

with populations in phase IV of smoking dependence report

no such differences (Villalb, Rodriguez-Sanz, Villegas,

Borrell, 2009; Wilson et al., 1992). The absence of sex

differences in our study may be attributable to this, or to the

intensive intervention involved in multicomponent therapy.

Although some studies have found a higher incidence

of relapse in women (Heatherton, Kozlowsky, Frecker, &

Fagerstrm, 1991), others report a substantial improvement

in womens results when psychological therapy is added to

pharmacological treatment (Nern & Jan, 2007) but this

is an aspect requiring further research.

Educational level is associated with success of the therapy,

as various studies have shown (Fernndez et al., 2001; Piper et

al., 2010), and the fact of receiving multicomponent therapy

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1

42

Antnia Raich, Jose Maria Martnez-Snchez, Emili Marquilles, Ldia Rubio, Marcela Fu and Esteve Fernndez

following psychological therapy after the third smokingfree month is effective for the maintenance of abstinence

(Hajek et al., 2013). Likewise, various reviews have shown

how group therapy, cognitive-behavioural therapy and

interventions with intensive follow-up are more efficacious

in the long term (Bauld et al., 2010; Hall, Humfleet, Muoz,

Reus, Robbins, Prochaska, 2009).

We observed a clear advantage of nicotine replacement

therapy compared to varenicline. Given that this was a

descriptive study, it should be borne in mind that there

may be bias in relation to the selection of pharmacological

options, since they were not assigned randomly; hence,

we cannot draw the kinds of causal conclusions that could

be drawn from a study with experimental design. These

differences may be due to the fact that greater efficacy of

varenicline for reducing symptoms of craving (Stapleton

et al., 2008) would hinder the learning of coping strategies

for craving on the part of these patients. This is why after

the end of the pharmacological treatment we see a higher

relapse rate. Since we are talking about patients with serious

difficulties for quitting smoking, there may be an influence

of poor ability to apply relapse-prevention strategies. If this

were indeed the case, nicotine replacement therapy would

emerge as the most appropriate pharmacological treatment

for multicomponent therapy interventions with these types

of patients, while varenicline would be more suitable for

patients who had not previously tried and failed to quit,

who would not be followed-up after the pharmacological

treatment, or who did not receive psychological treatment,

though this hypothesis would need to be tested with specially

designed studies.

It would be useful to analyze therapy adherence according

to the characteristics of participants who completed

the treatment, since this would provide information on

predictors of adherence to multicomponent therapy and

would help in the consideration of possible aspects to

improve with a view to increasing it.

The main limitation of the present study concerns the

time dimension. The fact of the sample being recruited over

a long period (9 years) means that socio-cultural variables

(e.g., legislative changes with regard to the prohibition of

smoking in public spaces, changes in societys perception of

the risks involved in smoking) could be having an effect that

we have not controlled for. Thus, it may be that the 2005

legislation restricting smoking in public had some influence

on peoples motivation to give up smoking. On the other

hand, though, the fact that the smokers in our sample had

homogeneous characteristics (high level of dependence,

many with previous pathologies, several attempts to quit)

brings some correctional elements, so that this aspect does

not influence the results as much as it would in a study with

the general population. Another limitation is not having

a record of the exact date of relapse, as this prevents us

from knowing whether a patient starts smoking again and

the fact that patients with schizophrenia or severe psychotic

disorders were directly excluded. Though perhaps the most

relevant factor is the environment in which the treatment

programme took place, since the smoking cessation unit is

part of the hospitals mental health department in which

patients receive psychiatric follow-up. We believe that this

may have led to greater adherence to the treatment and

the sessions, as well as better monitoring and adjustment

of the psychiatric treatment according to patients progress

towards giving up the habit, facilitated by the coordination

between the professionals at the smoking cessation unit

and the mental health department. Previous studies in

similar environments, indeed, have found higher rates

of smoking cessation in these types of patient (CepedaBenito et al., 2004; Fagerstrm & Aubin, 2009). Finally, it

is reasonable to think that the intensive treatment involved

in multicomponent therapy improves the results of these

patients, as some authors have already suggested (Brown et

al., 2001; Himelhoch & Daumit, 2003).

In the present study, multicomponent therapy with or

without pharmacological treatment improves abstinence

rates at the 12-month follow-up. If we focus on the 81 patients

that opted for psychological treatment only, we can observe

a substantial smoking cessation rate that reveals the effect of

psychological therapy even without its reinforcement with

pharmacological treatment, as also shown in several previous

studies (Killen et al., 2008). Given that the data were analyzed

on an intent-to-treat basis, the group of 81 participants that

received the therapy without pharmacological treatment

incudes patients who dropped out during the first phase of

the treatment, so that we may actually be underestimating

the results yielded by psychological therapy without

pharmacological treatment. Focusing on the differences

between abstinence at one month and at twelve months, it

can be seen that the psychological treatment only group

lost 11% of patients to relapse, while the psychological plus

pharmacological treatment group lost 44%. This leads us to

think that those who achieve abstinence in the first month

without pharmacological treatment are keener to maintain

their abstinence than those who achieve it with the help of

pharmacological treatment, though it would be necessary to

carry out more studies with experimental design to be able

to confirm this hypothesis.

As regards pharmacological treatments, it was found

that all of the play an important role in all phases of the

process (Hajek, Stead, West, Jarvis, Hartmann-Boyce, &

Lancaster, 2013; Tinich & Sadler, 2007). The results suggest

that pharmacological treatment increases the likelihood of

success in quitting smoking in the first three months, and

that once a period of abstinence has been attained, the

probability of maintaining abstinence in the medium and

long term increases substantially (PHS Guideline Update

Panel 2008). A study with experimental design in patients

with characteristics similar to those in our study showed that

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1

43

Smoking cessation after 12 months with multi-component therapy

Antnia Raich, Jose M. Martnez-Sanchez and Esteve

Fernndez received funding from the Instituto de Salud

Carlos III (RETICC, beca RD12/0036/0053) and the

Departament dEconomia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de

Catalunya (2009 SGR 192).

This work received the XVI Premi del Bages de Cincies

Mdiques (XVI Bages Prize for Medical Science), awarded by

the Acadmia de Ciencies Mdiques de Catalunya filial del Bages

and the Collegi Oficial de Metges de Barcelona.

therefore drops out of the programme, or first drops out

of the programme which in turn leads to smoking relapse.

An advantageous aspect of the study is the fact of its

using co-oximetry to confirm abstinence, as it gives much

greater validity to the results than if we had only the patientreported information.

The restricted geographical context of the study may seem

like a limitation, given that the whole sample is concentrated

in the same smoking cessation unit, which attends to a

population with particular socio-cultural characteristics and

served by a specific health-service structure, and this could

limit the generalization potential of the results. Nevertheless,

the population is a heterogeneous one in terms of sociocultural characteristics, since both rural and urban regions

are represented: Manresa is a city of over 70,000 inhabitants,

situated within the third ring of the Barcelona metropolitan

area and with an urban culture, while other parts of the

sample are drawn from regions of central Catalonia with

primarily rural socio-economic environments.

The fact of being a clinical study carried out in a real

and natural context, that it seeks the most appropriate

treatment according to the patients characteristics and

that the data analysis is carried out on an intent-to-treat

basis are relevant aspects of the present study, enabling

it to provide information that complements the results

obtained in clinical trials conducted in ideal conditions

(Brown et al., 2001; Garrison & Dugan, 2009; Tinich et

al., 2007). In sum, we believe that this study permits as to

contribute data on the effectiveness of multicomponent

therapy in the clinical context, with heavy smokers and in

a real environment.

The results obtained in the present study show how

multicomponent therapy facilitates smoking cessation at

one, three, six and twelve months. Socio-environmental

characteristics such as higher educational level and not

living with smokers predicted success in quitting smoking

through multicomponent therapy, but this was not the

case for other variables, such as sex, smoker characteristics

and personal psychiatric antecedents. The combination of

pharmacological and psychological treatment increased

success rates in the multicomponent therapy, and

psychological therapy alone also yielded positive results,

though they were more limited in this case. In the light

of these results, which require confirmation through

experimental studies with better control of other possible

determinants of dropout and success, we might consider

a more generalized application of this type of therapy,

especially with heavy or recalcitrant smokers.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

References

Alonso-Prez, F., Alonso-Cardeoso, C., Garca-Gonzlez, J.

V., Fraile-Cobos, J. M., Lobo-Llorente, N., & Secades-Villa,

R. (2014). Effectiveness of a multicomponent smoking

cessation intervention in primary care. Gaceta Sanitaria,

28, 222-224.

Baer J. S., & Marlatt G. A. (1991). Maintenance of smoking

cessation. Clinics in Chest Medicine, 12, 793-800.

Bauld, L., Bell, K., McCullough, L., Richardson, L., &

Greaves, L. (2010). The effectiveness of NHS smoking

cessation services: a systematic review. Journal of Public

Health, 32, 71-82.

Becoa E., & Vazquez F. L. (1998).The course of relapse

across 36 months for smokers from a smoking-cessation

program. Psychological Reports; 82:143-146.

Becoa, E., & Mguez, M. C. (2008). Group behavior therapy

for smoking cessation. Journal of Groups in Addiction &

Recovery, 3, 63-78.

Belleudi, V., Bargagli, A. M., Davoli, M., Di Pucchio, A., Pacifici,

R., Pizzi, E., ... Perucci, C. A. (2006). Characteristics and

effectiveness of smoking cessation programs in Italy.

Results of a multicentric longitudinal study. Epidemiologia

e Prevenzione, 31, 148-157.

Bjornson, W., Rand, C., Connett, J. E., Lindgren, P., Nides,

M., Pope, F., ... OHara, P. (1995). Gender differences in

smoking cessation after 3 years in the Lung Health Study.

American Journal of Public Health, 85, 223-230.

Brown, R. A., Kahler, C. W., Niaura, R., Abrams, D. B., Sales,

S. D., Ramsey, S. E., ... Miller, I. W. (2001). Cognitive

behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 471-480.

Cahill, K., Stevens, S., & Lancaster, T. (2014). Pharmacological

treatments for smoking cessation. JAMA, 311, 193-194.

Cepeda-Benito, A., Reynoso, J. T., & Erath, S. (2004). Metaanalysis of the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy for

smoking cessation: differences between men and women.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 712-722.

de Leon, J., Diaz, F. J., Becoa, E., Gurpegui, M., Jurado, D.,

& Gonzalez-Pinto, A. (2003). Exploring brief measures

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Anna Arnau, Rosa Cobacho, Joan Taberner

and Alejandro Gella for their help at different stages of the

study.

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1

44

Antnia Raich, Jose Maria Martnez-Snchez, Emili Marquilles, Ldia Rubio, Marcela Fu and Esteve Fernndez

Likura, Y. (2010). Classification of OCD in terms of response

to behavior therapy, manner of onset, and course of

symptoms. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi= Psychiatria et

Neurologia Japonica, 113, 28-35.

Marlatt, G. A., Curry, S., & Gordon, J. R. (1988). A longitudinal

analysis of unaided smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 56, 715-720.

Middleton, E. T., & Morice, A. H. (2000). Breath carbon

monoxide as an indication of smoking habit. CHEST

Journal, 117, 758-763.

Nern I., & Jan M. (2007). Libro blanco sobre mujeres

y tabaco. Comite Nacional para la prevencin del

Tabaquismo. Zaragoza: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo.

Nern I., Novella P., Beamonte A., Gargallo P., Jimenez-Muro

A., & Marqueta A.(2007) Results of smoking cessation

therapy in a specialist unit. Archives of Bronconeumology,

43, 669-673.

Perkins, K. A., & Scott, J. (2008). Sex differences in longterm smoking cessation rates due to nicotine patch.

Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10, 1245-1251.

PHS Guideline Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. Treating

tobacco use and dependence: (2008) update U.S. public

health service clinical practice guideline executive

summary. Respiratory Care, 53, 1217-1222.

Piper, M. E., Cook, J. W., Schlam, T. R., Jorenby, D. E., Smith,

S. S., Bolt, D. M., & Loh, W. Y. (2010). Gender, race,

and education differences in abstinence rates among

participants in two randomized smoking cessation trials.

Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12, 647-657.

Ramon, J. M., & Bruguera, E. (2009). Real world study to

evaluate the effectiveness of varenicline and cognitivebehavioural interventions for smoking cessation.

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public

Health, 6, 1530-1538.

Ranney, L., Melvin, C., Lux, L., McClain, E., & Lohr, K. N.

(2006). Systematic review: smoking cessation intervention

strategies for adults and adults in special populations.

Annals of Internal Medicine, 145, 845-856.

Siahpush, M., McNeill, A., Borland, R., & Fong, G. T. (2006).

Socioeconomic variations in nicotine dependence, selfefficacy, and intention to quit across four countries:

findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC)

Four Country Survey. Tobacco Control, 15(suppl 3), iii71iii75.

Silagy, C., Lancaster, T., Stead, L., Mant, D., & Fowler, G.

(2004). Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking

cessation. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 3,

CD000146.

Stead, L. F., & Lancaster, T. (2005). Group behaviour therapy

programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database

Systematic Review, 2, CD001292.

Stead, L. F., & Lancaster, T. (2012). Behavioural interventions

as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation.

Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 12, CD009670.

of nicotine dependence for epidemiological surveys.

Addictive Behaviors, 28, 1481-1486.

Fagerstrm, K., & Aubin, H. J. (2009). Management of

smoking cessation in patients with psychiatric disorders.

Current Medical Research and Opinion, 25, 511-518.

Fernndez, E., Carn, J., Schiaffino, A., Borrs, J., Salt,

E., Tresserras, R., ... Segura, A. (1998). Determinants of

quitting smoking in Catalonia, Spain. Gaceta Sanitaria, 13,

353-360.

Fernandez, E., Garcia, M., Schiaffino, A., Borras, J. M.,

Nebot, M., & Segura, A. (2001). Smoking initiation and

cessation by gender and educational level in Catalonia,

Spain. Preventive Medicine, 32, 218-223.

Fernndez, E., Schiaffino, A., Borrell, C., Benach, J., Ariza,

C., Ramon, J. M., ... Kunst, A. (2006). Social class,

education, and smoking cessation: long-term follow-up

of patients treated at a smoking cessation unit. Nicotine &

Tobacco Research, 8, 29-36.

Fiore, M. C., Jan, C. R., Baker, T. B., Bailey, W. C., Benowitz,

N. L., & Curry, S. J. (2009). Treating Tobacco Use and

Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: US Department

of Health and Human Services; May 2008.

Garrison, G. D., & Dugan, S. E. (2009). Varenicline: a firstline treatment option for smoking cessation. Clinical

Therapeutics, 31, 463-491.

Hajek, P., Stead, L. F., West, R., Jarvis, M., Hartmann-Boyce, J.,

& Lancaster, T. (2013). Relapse prevention interventions

for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 8.

Hall, S. M., Humfleet, G. L., Muoz, R. F., Reus, V. I., Robbins,

J. A., & Prochaska, J. J. (2009). Extended treatment of

older cigarette smokers. Addiction, 104, 1043-1052.

Haustein, K. O. (2004). Smoking and low socio-economic

status. Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverband der Arzte des

Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Germany)), 67, 630-637.

Hays, J. T., Ebbert, J. O., & Sood, A. (2009). Treating tobacco

dependence in light of the 2008 US Department of

Health and Human Services clinical practice guideline.

In Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 84, 730-736.

Hays, J. T., Leischow, S. J., Lawrence, D., & Lee, T. C. (2010).

Adherence to treatment for tobacco dependence:

Association with smoking abstinence and predictors of

adherence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12, 574-581.

Heatherton, T. F., Kozlowski, L. T., Frecker, R. C., &

Fagerstrm, K. O. (1991). The Fagerstrm test for

nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrm

Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86,

1119-1127.

Himelhoch, S., & Daumit, G. (2003). To whom do psychiatrists

offer smoking-cessation counseling?. American Journal of

Psychiatry, 160, 2228-2230.

Killen, J. D., Fortmann, S. P., Schatzberg, A. F., Arredondo,

C., Murphy, G., Hayward, C., ... Pandurangi, M. (2008).

Extended cognitive behavior therapy for cigarette

smoking cessation. Addiction, 103, 1381-1390.

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1

45

Smoking cessation after 12 months with multi-component therapy

Stapleton, J. A., Watson, L., Spirling, L. I., Smith, R., Milbrandt,

A., Ratcliffe, M., & Sutherland, G. (2008). Varenicline in

the routine treatment of tobacco dependence: a prepost

comparison with nicotine replacement therapy and an

evaluation in those with mental illness. Addiction, 103,

146-154.

Tinich, C., & Sadler, C. (2007). What strategies have you

found to be effective in helping patients to stop smoking?.

ONS Connect, 22, 14.

Villalb, J. R., Rodriguez-Sanz, M., Villegas, R., & Borrell,

C. (2009). Changes in the population smoking patterns:

Barcelona, 1983-2006. Medicina Clinica, 132, 414-419.

Wilkes, S. (2008). The use of bupropion SR in cigarette

smoking cessation. International Journal of Chronic

Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 3, 45-53.

Wilson, D., Wakefield, M., Owen, N., & Roberts, L. (1992).

Characteristics of heavy smokers. Preventive Medicine, 21,

311-319.

Wu, P., Wilson, K., Dimoulas, P., & Mills, E. J. (2006).

Effectiveness of smoking cessation therapies: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 6, 300.

Yez, A., Leiva, A., Gorreto, L., Estela, A., Tejera, E., &

Torrent, M. (2013). El instituto, la familia y el tabaquismo

en adolescentes. Adicciones, 25, 253-259.

ADICCIONES, 2015 VOL. 27 ISSUE 1

46

Вам также может понравиться

- Psicología Del Trabajo, 2012Документ375 страницPsicología Del Trabajo, 2012fataldjОценок пока нет

- Test PersonalidadДокумент8 страницTest PersonalidadLizanka Salazar50% (2)

- Presentación Cuestionario Big Five (BFQ)Документ18 страницPresentación Cuestionario Big Five (BFQ)fataldj100% (2)

- Fasciola HepaticaДокумент12 страницFasciola HepaticaTriana Mondragon50% (2)

- Respeta MedicaДокумент1 страницаRespeta MedicaAngel TrinidadОценок пока нет

- 1º Entrevista Semiestructurada (Muñoz, 2001)Документ3 страницы1º Entrevista Semiestructurada (Muñoz, 2001)fataldj100% (2)

- CasoДокумент76 страницCasoKathy Morocho GrandaОценок пока нет

- Piaget Jean - Psicologia Y EpistemologiaДокумент67 страницPiaget Jean - Psicologia Y EpistemologiamarzarmarОценок пока нет

- Fundamentos de Neurolinguística. A. R. LuriaДокумент335 страницFundamentos de Neurolinguística. A. R. LuriaLu Ordóñez94% (31)

- Informe Médico Legal Padre - Karen PardoДокумент3 страницыInforme Médico Legal Padre - Karen PardoKaren Gianina Pardo FloresОценок пока нет

- Dientes Retenidos PDFДокумент10 страницDientes Retenidos PDFAnonymous 7XPRJCaKLОценок пока нет

- La Entrevista de DesarrolloДокумент9 страницLa Entrevista de DesarrollofataldjОценок пока нет

- Evaluación Contextos 1, ClínicosДокумент17 страницEvaluación Contextos 1, ClínicosfataldjОценок пока нет

- Ficha Tecnica Partner TepeeДокумент9 страницFicha Tecnica Partner TepeefataldjОценок пока нет

- Capítulo 2 OCR y Cuadro Muñoz 2002Документ64 страницыCapítulo 2 OCR y Cuadro Muñoz 2002fataldjОценок пока нет

- Actividades Orientacion LaboralДокумент1 страницаActividades Orientacion LaboralfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент17 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент7 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Adaptacion Proyecto Convalidaciones Estudios GradoДокумент1 страницаAdaptacion Proyecto Convalidaciones Estudios GradofataldjОценок пока нет

- Intervencion Neuropsicológica y FarmacológicaДокумент4 страницыIntervencion Neuropsicológica y FarmacológicafataldjОценок пока нет

- Capítulo 1 e Índice - OCRДокумент42 страницыCapítulo 1 e Índice - OCRfataldj100% (2)

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент12 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент63 страницыTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент7 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент7 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент9 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент12 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент14 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, Practicasfataldj100% (1)

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент12 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, Practicasfataldj100% (1)

- Operativización de Conductas ObsersablesДокумент1 страницаOperativización de Conductas ObsersablesfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент10 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Tecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasДокумент8 страницTecnicas de Modificacion de Conducta, PracticasfataldjОценок пока нет

- Neuropsicología de Las Funciones Ejecutivas y La Corteza P.F.Документ252 страницыNeuropsicología de Las Funciones Ejecutivas y La Corteza P.F.fataldj0% (2)

- Neuropsicología de Las Funciones Ejecutivas y La Corteza P.F.Документ252 страницыNeuropsicología de Las Funciones Ejecutivas y La Corteza P.F.fataldj100% (7)

- Ejercicios de RelajacionДокумент1 страницаEjercicios de RelajacionfataldjОценок пока нет

- Trabajo Practico N1 Tecnica de Lavado de ManosДокумент3 страницыTrabajo Practico N1 Tecnica de Lavado de ManosKaterin UlloaОценок пока нет

- Embarazo EctopicoДокумент9 страницEmbarazo EctopicoCielo Valentina Garcia LopezОценок пока нет

- Diseños AnaliticosДокумент7 страницDiseños AnaliticosGuillermo Daniel BritoОценок пока нет

- EdemaДокумент3 страницыEdemaalba jimenezОценок пока нет

- OxigenoterapiaДокумент20 страницOxigenoterapiaClaudia AndreaОценок пока нет

- Infecciones Asociadas A La Atención de La Salud (IAAS)Документ23 страницыInfecciones Asociadas A La Atención de La Salud (IAAS)Irving Arellano RivasОценок пока нет

- Modulo 1 Perito JudicialДокумент36 страницModulo 1 Perito JudicialcastimaxОценок пока нет

- Fractura de Cadera-1 2OKIДокумент14 страницFractura de Cadera-1 2OKIbellОценок пока нет

- Clamidiosis AviarДокумент23 страницыClamidiosis AviarPilar Popa100% (1)

- 0000000774cnt 2015 04 Lineamientos VaricelaДокумент45 страниц0000000774cnt 2015 04 Lineamientos VaricelaBrunel Arturo LGОценок пока нет

- Higiene y Aseo de Pacientes. Poster 05 PDFДокумент1 страницаHigiene y Aseo de Pacientes. Poster 05 PDFLalo Lobato0% (1)

- Proyecto Agosto2023Документ66 страницProyecto Agosto2023MariselaTudaresОценок пока нет

- Lactancia Materna OKДокумент13 страницLactancia Materna OKKimberlyChoqueGallegosОценок пока нет

- Caso Clínico RAMДокумент6 страницCaso Clínico RAMRafael CenОценок пока нет

- Historia de La Medicina FinalДокумент15 страницHistoria de La Medicina FinalBrayan Abel Estela CotrinaОценок пока нет

- Calidad Del Cuidado Enfermero en Un Centro Quirúrgico: Experiencia en Un Hospital de Ibarra, EcuadorДокумент5 страницCalidad Del Cuidado Enfermero en Un Centro Quirúrgico: Experiencia en Un Hospital de Ibarra, EcuadorDiana VargasОценок пока нет

- Cotología MétodosДокумент43 страницыCotología MétodosJorge LucasОценок пока нет

- Manual Medico 2020 V 2.0Документ32 страницыManual Medico 2020 V 2.0Jessica Galvez HormazabalОценок пока нет

- Pañales Nueva Eps Gloria OlayaДокумент3 страницыPañales Nueva Eps Gloria OlayaJhulliana Guerra SernaОценок пока нет

- Alteraciones Del Crecimiento FetalДокумент13 страницAlteraciones Del Crecimiento FetalJair Cruz Isopo100% (2)

- ArbovirusДокумент3 страницыArbovirusLara Cristina Pérez MolinaОценок пока нет

- Enfermeria Ulceras PresionДокумент25 страницEnfermeria Ulceras PresionDaniel BlanquetОценок пока нет

- Protocolo Individual 3Документ2 страницыProtocolo Individual 3Diego Alejandro Caraballo SánchezОценок пока нет

- Cuadro Comparativo Actividad 6 ENFERMEDADES Ok.Документ8 страницCuadro Comparativo Actividad 6 ENFERMEDADES Ok.maritzaОценок пока нет

- Itu en Embarazada Proceso de EnfermeríaДокумент21 страницаItu en Embarazada Proceso de EnfermeríaMARYVON50% (2)