Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Agri Sci - Ijasr - Assessment of Relation Between Physical - Kamalaja

Загружено:

TJPRC PublicationsОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Agri Sci - Ijasr - Assessment of Relation Between Physical - Kamalaja

Загружено:

TJPRC PublicationsАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

International Journal of Agricultural Science

and Research (IJASR)

ISSN(P): 2250-0057; ISSN(E): 2321-0087

Vol. 5, Issue 3, Jun 2015, 219-226

TJPRC Pvt. Ltd.

ASSESSMENT OF RELATION BETWEEN PHYSICAL STRESS AND

PHYSICALFITNESS USING TREADMILL IN FEMALE ADULTS

T. KAMALAJA1 & J. DEEPIKA2

1

Scientist, AICRP, Department of Foods and Nutrition, Faculty of Home Science, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

1,2

Professor, Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Andhra Pradesh, India

Research Scholar, Department of Resource Management and Consumer Sciences, College of Home Science,

Hyderabad, Telangana, India

ABSTRACT

Physical fitness is the potential capacity of an individual for making adequate functional adjustments to increase

metabolic demands. One obvious approach to evaluate physical fitness is the physical work capacity of an individual.

It can be influence by age, sex, body size etc. The study was carried out on 30 female college going postgraduate students.

Physical work capacity measured basing on activity time by using treadmill test. During treadmill test L5 and L6 load

exercises correlated to Hb level and activity time, total energy expenditure with activity time, negative correlation was

observed between heart rate recovery time and Lean Body Mass and no significance difference was observed in Pulse

Pressure.

KEYWORDS: Physical Fitness, Haemoglobin (Hb), Blood Pressure (B. P.), Lean Body Mass (LBM), Basal Metabolic

Rate (BMR), Body Mass Index (BMI), Total Energy Expenditure (TEE), Pulse Pressure, Activity Time (AT) Tread Mill

Test

INTRODUCTION

Physical fitness is a general state of health and well-being and, more specifically, the ability to perform aspects

of sports or occupations. Physical fitness is generally achieved through correct nutrition, (Tremblay, 2010) moderatevigorous physical activity, (De groot, 2010) exercise and rest, (Malina, 2010). It is a set of attributes or characteristics seen

in people and which relate to the ability to perform a given set of physical activities.

Physical stress and physical fitness has been called a global epidemic by the World Health Organization

(world health organization, 2000). The prevalence of physical stress and physical fitness is especially dramatic in

economically developed and developing countries (Wang and Lobstein, 2006) and not only in adults but also in children

and adolescents.

For instance, physical stress in adults and adolescents are more likely to suffer from cardiovascular, metabolic,

pulmonary, psychosocial disorders. Even if these conditions or disorders are not manifested during childhood, being

physical stress in adolescents increases the risk of illness in adulthood (Daniels, 2006). Hence, it is critical to identify risk

factors for physical stress and fitness in adults and adolescents.

The heritability of predisposition for a high body mass index (BMI) or body fat content is between 25 and

40% (Bouchard et al., 1997), which suggests that other factors such as environmental factors may also play a critical role.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

220

T. Kamalaja & J. Deepika

According to Bouchard et al., (1997) both the family environment and genetic predisposition influence the development of

body fat content and distribution. Other important factors include lifestyle factors such as physical activity (PA),

nonsmoking, high-quality diet, sedentary activities and normal weight (Pronk etal, 2004) Lifestyle factors are also

important in the description of the obesogenic environment that is based on the four pillars family, sport and leisure time,

eating behavior and social education (wabitsch, 2004).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship between physical stress and physical fitness in relation

to different parameters

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In the present study 30 female post graduate and PhD students were selected from Acharya N.G.Ranga

Agricultural University. And all the subjects were in the age group of 20 to 30 years. The data collected on Socio

Economic status of selected subjects was assessed through a structured schedule developed by Thimmayamma et al (1987).

Body composition such as total body fat (BF), lean body mass (LBM) and total body water (BW). BMI and Basal

metabolic rate (BMR) were measured using body composition measuring equipment Bioelectrical Impedance named as

Body stat. The heart rates were monitored on a online polar heart monitor throughout the exercise period and recovery

time. Physical fitness was tested in lab conditions with the help of Graded maximal exercise test (GXT) under laboratory

conditions using the standard Bruce protocol on the treadmill to identify maximal performance of an individual

The parameters studied are Heart Rate, B.P., Pulse, Energy Expenditure and Body composition such as total body fat (BF),

lean body mass (LBM) and total body water (BW) Body Mass Index and Basal Metabolic Rate based on activity time.

All the data was expressed through mean and standard deviation. Significance changes in each parameter during treadmill

test was assessed through F-test, multiple correlations and multiple regressions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Family Particulars of Subjects

Information pertaining to family background of selected subjects was analyzed and presented in table 1

Table 1: Family Particulars of Selected Subjects

Family Particulars

No

Per cent

Type of Family :

30

100

Nuclear

0

Joint

Size of the Family

4

13

Below 3

19

63

4-5

7

24

Above 6

No. of Male Members in a Family

Below 2

20

67

3-4

9

30

Above 5

1

3

No. of Female Members in a Family

1

6

20

2

11

37

3

8

27

4

4

13

5

1

3

Marital Status of Subjects

Impact Factor (JCC): 4.7987

NAAS Rating: 3.53

221

Assessment of Relation between Physical Stress and

Physicalfitness Using Treadmill in Female Adults

Table 1: Contd.,

Married

4

13

Unmarried

26

87

Educational Status

P.G

26

87

PhD

4

13

Family Income Per Annum (Rs)

75,000-1,00,000

5

17

1.00,000-1,50,000

6

20

1,50,000-2,00,000

9

30

2,00,000-2,50,000

5

17

2,50,000-3,00,000

5

16

All the subjects were from nuclear family (100 per cent) and majority had four (33 per cent) or five (30 per cent)

members in family with maximum two male (40 per cent) and two female (37 per cent) members. Most of the subjects

were unmarried (87 per cent) and doing post graduation (87 per cent). Family income of subjects ranged mostly (30 per

cent) between one and half to two lakhs. This was followed by one to one and half lakh (20 per cent). The major reasons

could be due to regular, private or government jobs of earning members in the respondent families.

Grouping of Subjects as per Activity Time in Treadmill Test

Table 2: Grouping of Subjects as Per Activity Time in Treadmill Test

Time Ranges (Mt)

Treadmill Ranges:

10 -12

>12 - 14

>14 - 16

>16 - 18

No

16

7

5

2

Subjects

Per Cent

Mean Sd

53

11.3 0.78

23

13.1 0.27

17

14.9 0.20

7

16.5 0.50

The subjects were grouped as per activity time of treadmill test.

The AT for majority (53 per cent) was 10 to 12 mt followed by >12 to 14 mt (23 per cent), >14 to 16 mt (17 per

cent) and least (7 per cent) had > 16 to 18 mt, during treadmill test (Table 2).

Changes in Parameters during Treadmill Test

The activity time is grouped into 4 periods that is 10 to 12 mt, >12 to 14 mt, >14to 16mt and >16 to 18. (Table 3).

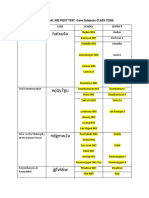

Table 3: Changes in Parameters of Subjects during Treadmill Test, Basing on Activity Time

Parameters

Rest

L1

L2

L3

L4

L5

L6

AT

TEE

15

www.tjprc.org

Activity Time Ranges (mt)

>14 16

10 12 (16)

>12 14 (7)

>16 18 (2)

(5)

Heart rates during Workloads (bpm)

82 7.65

77 3.14

76 8.16

81

127 17.18

117 6.43

124 8.03

113

134 11.81

124 9.34

139 6.85

123 8.00

153 12.4

144 6.54

153 8.52

142 10.5

178 7.26

170 8.85

178 7.73

164 8.50

183 8.27

193 6.49

187 0.50

196 0.00

197 0.50

11 0.78

13 0.27

15 0.20

17 0.50

60 6.15

77 3.46

97 4.24

112 3.00

Heart Rate (bpm) Recovery Time (mt)

108 6.52

108 7.90

-

Correlation

Regression

-0.1797

-0.1345

-0.0754

-0.1803

-0.2705

0.8244**

0.6510**

0.9800**

0.491

0.693

-0.598

-0.678

0.64

1.344

-1.277

9.149**

-0.6575**

0.83

editor@tjprc.org

222

T. Kamalaja & J. Deepika

Table 3: Contd.,

111 9.11

111 1.00

0.5447**

107 1.90

0.289

B.P Systolic (mm Hg)

Table 3: Contd.,

Before

106 6.88

107 6.77

108 7.17

114 1.5

0.1644

After

126 11.3

127 71.4

133 3.40

129 5.50

0.2364

B.P Diastolic (mm Hg)

Before

70 4.38

72 4.94

74 9.76

70 0.50

0.93

After

73 7.67

72 8.33

80 8.11

74 2.00

0.2293

Pulse Rate (bpm)

Before

78 19.67

85 11.3

81 5.27

74 2.00

0.1666

After

118 9.13

126 13.4

143 3.07

134 13.5

0.6126**

1356

BMR (K.cal /

1272 110

1295 62.5

1472 93.3

0.3852*

113.6

24Hr)

21 3.69

21 2.98

21 1.42

23 0.35

-0.0246

BMI

Bodycomposition (Per Cent)

LBM

70 4.25

72 4.5

74 3.6

74 2.4

-0.3747*

Fat

30 4.95

28 4.4

26 2.5

26 2.4

0.4614*

Body water

52 4.2

53 3.37

53 3.2

52.8 0.7

0.1667

Hb (g/dl)

10 1.6

12 1.45

13 1.08

14 0.00

0.6825**

F =37.54552**

* Significance at 5%,

** Significance at 1%

L1 to L6 are workloads with 3 mt increase

20

25

110

-

95 0.30

105 0.00

0.759

0.491

-0.964

-0.438

-0.362

-0.078

-0.099

0.905

-

During rest period, the heart rates ranged between 76 bpm (> 14 16 mt group) and 82 bpm (10 -12 mt group).

During load exercises, a trend was observed with decreasing AT (>16 18 to 10 -12 mt), an increase in heart rate (164 to

178 bpm) was observed. Negative insignificant correlation was observed up to L4 work load test and after that positive

significant (5%) correlation was observed between heart rate and AT.

When AT was between >14 16 mt, great variation was observed in heart rates during different work loads.

Maximum number (16) of subjects fell into 10 12 mt group followed by >12 to14 mt (7), >14 16 mt (5) and least (2) in

higher AT group i.e. >16 to 18 The group who could perform activity for to 10 12 mt, discontinued exercise after L4

level. While > 14 -16 and >16 to 18 mt at L6 level. The mean AT ranged from 11 mt to (10 to12 mt AT group) to 17 mt.

The total energy expenditure showed a perfect positive trend with AT it has increased from 60 K.Cal (10 -12 mt

AT) to 112 K.Cal (16 to 18 mt AT). Highly significant (1 per cent) positive correlation and regression was observed

between total energy expenditure and AT.

Heart rate recovery was also assessed and found that the recovery period ranged between 15 to 25 mt. The lowest

and highest AT group recovered in 20 mt while the rest two groups in 25 mt. Correlation was observed between 15 mt

recovery time as well as 20 mt recovery times and AT.

The initial systolic B. P was similar among all the groups except in > 16 to 18 group following load test the group

falling into > 14 -16 mt group had highest (133 mm Hg) systolic and diastolic (80 mm Hg) B. P. While diastolic B. P

showed fluctuations with increased AT. The diastolic B. P increased slightly in all the groups and increase was highest in

>14 to 16 mt (80 mm Hg) AT group. The pulse rate initially ranged between 74 bpm (>16 -18 mt AT group) to 85 bpm

(>12 14 mt AT group). This has increased following load exercise and the increase was highest (143 bpm) in 14 -16 mt

AT group. The pulse rate before exercise showed no significance but after exercise highly significant (1 per cent)

correlation was observed between pulse rates and AT.

Impact Factor (JCC): 4.7987

NAAS Rating: 3.53

223

Assessment of Relation between Physical Stress and

Physicalfitness Using Treadmill in Female Adults

The BMR which was recorded initially, increased with increase in AT. For lower AT group (10 12 mt) lower

BMR (1272 K.Cal / 24 Hr) and high AT (>16 18) group had high BMR (1472 K. Cal / 24 Hr). Significant (5 per cent)

positive correlation was observed between AT and BMR.

BMI of all the groups was similar (21) except for high AT (>16 18 mt) group (23).

The LBM showed a proportional relationship with AT. The LBM increased from 67 per cent (10 12 mt group)

to 74 per cent (>16 18 mt group). Significant (5 per cent) correlation was observed between LBM and AT. The body fat

content decreased with increase in AT except for high (>16 18 mt group) AT group. The fat per cent ranged between 23

(>14 16 mt group) and 30 (10-12 mt group) and significant positive correlation (5 per cent) was observed betweens AT

and fat content. Body water remained same in all groups when classified basing on AT.

The lowest group had 10 g/dl while > 16 to 18 mt group had highest Hb level (14 g/dl). High positive significance

(1 per cent) was observed between Hb levels and AT.

The F value showed high significance (1 per cent) for AT.

Total Energy Expenditure

The energy expenditure during different work loads (Table 4) increased from initial 7 to 9 calories (100 per cent)

to 60 to 70 calories (83 per cent). Majority of subjects (83 per cent) could stand for a speed of 6.4 kmph and negligible (13

per cent) could continue up to 8.9 kmph with energy expenditure of 100-110 K.Cal and 120 to 130 K.Cal for the activity.

Most (83 per cent) of the subjects discontinued activity after L4 in 51 to 70 range followed by L5 load with 75 to 85 energy

expenditure and few (7 per cent) were terminated at L4 level with energy expenditure of 51 to 60. All the rest of subjects

discontinued at L5 with energy range of 86 to 95 (20 per cent) or L6 with 100-110 range (10 per cent) or 121-130 range (3

per cent) energy spent.

Table 4: Energy Expenditure of Subjects, During Different Workloads, in Treadmill Test

Work Loads

L1

L2

L3

L4

L5

L6

Energy Expenditure

(K. Cal)

7-9

20-21

21 -22

30-40

40-50

40-50

50-60

60-70

75-85

85-95

100-110

110-120

120-130

No

Per cent

Mean SD

30

4

26

7

23

3

2

25

7

6

3

0

1

100

13

87

23

77

10

7

83

23

20

10

0

3

8 0.18

21

22

39 3.36

41 0.21

50 0.58

55 3.54

64 1.17

78 4

93 1.38

102 2.08

126 0.00

Changes in parameters during treadmill test basing on total energy expenditure was assessed and tabulated in

Table 4.

Basing on load of the exercise, body size, training of participant etc influence energy expenditure. Subjects were

given a package consisting of six load exercises and each load exercise was for a fixed period of 3 minutes.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

224

T. Kamalaja & J. Deepika

Energy expenditure increased with increase in activity except in the case of L4 load exercise. Under each load, the subjects

were further grouped basing on energy expenditure of When subjects were exposed to L1 load test a mean energy

expenditure 8 K Cal was observed. On continuing L2 load exercise, majority (87 per cent) of subjects TEE was 22 K.cal

and few (13 per cent) spent 21 K.cal. On subjecting to L3 load, majority (77 per cent) of subjects fell into higher (41 K.cal)

energy expenditure group. When subjects further continued load i.e.; at L4 (83 per cent) a mean energy expenditure of 64

K.cal was observed which higher range at that particular load is. Equal number of subjects, at L5 load had TEE of 78 K.cal

(23 per cent) and 93 K.cal (20 per cent). Very few (13 per cent) subjects remained up to L6 load and majority of them had

TEE of 102 K.cal (10 per cent).

From the above Table 4 it is clear that the subjects spent varying for same load test energy load but majority of the

subjects fell into the higher range energy expenditure. Under each load test, few subjects energy expenditure was on the

lower side for the same activity. The variation in energy expenditure could be considered due to differences in body size,

age, hereditary differences etc.

CONCLUSIONS

The physical performance was analyzed through treadmill test. Among all the exercises during treadmill test L5,

L6 load exercises correlated to Hb and AT indicating relationship between the parameters. No correlation was observed

between parameters followed by resting 15 to 20 mt. Recovery time correlated to BMI (1 per cent), Hb (1 per cent),.

AT (1 per cent), BMR (5 per cent) and LBM (5 per cent).

PFI analysis revealed poor performance by all the subjects. This can be evinced poor food and nutrient intake.

REFERENCES

1.

Bouchard, C., Malina, R. M and Perusse,L. 1997. Genetics of fitness and physical performance. Human kinetics.

2.

Daniels, S. R. 2006. The consequences of childhood overweight and obesity. Future Child. 16(1):47-67.

3.

de Groot, Lindgren, G. C and Fagerstrm, L. 2010. "Older adults' motivating factors and barriers to exercise to

prevent

falls". Scandinavian

Journal

of

Occupational

Therapy 18(2):

153160. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2010.487113.PMID 20545467.

4.

Malina, R. 2010. Physical activity and health of youth. Constanta: Ovidius University Annals, Series Physical

Education and Sport/Science, Movement and Health.

5.

Pronk, N. P., Anderson, L. H., Crain, A. L., Martinson, B. C., OConnor, P. J., Sherwood, N. E and Whitebird, R.

R. 2004. Meeting recommendations for multiple healthy lifestyle factors. Prevalence, clustering, and predictors

among adolescent, adult, and senior health plan members. Am J Prev Med, 27(2):25-33.

6.

Thimmmayamma B. V. S., 1987, A hand book of schedules and guidelines in socioeconomic and diet surveys,

National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, 1-67.

7.

Tremblay, Mark Stephen., Colley, Rachel Christine., Saunders, Travis John., Healy, Genevieve Nissa and Owen,

Neville. 2010. "Physiological and health implications of a sedentary lifestyle". Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and

Metabolism 35 (6): 725740.doi:10.1139/H10-079.

8.

Wabitsch, M. 2004. Children and adolescents with obesity in Germany. Call for action. Bundesgesundhbl -

Impact Factor (JCC): 4.7987

NAAS Rating: 3.53

Assessment of Relation between Physical Stress and

Physicalfitness Using Treadmill in Female Adults

225

Gesundheitsforsch - Gesundheitsschutz, 47(3):251-255.

9.

Wang, Y and Lobstein, T. 2006. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. IJPO. 1(1):11-25.

10. World Health Organisation. 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO

consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 894:1-253.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

Вам также может понравиться

- 2 33 1641272961 1ijsmmrdjun20221Документ16 страниц2 33 1641272961 1ijsmmrdjun20221TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Flame Retardant Textiles For Electric Arc Flash Hazards: A ReviewДокумент18 страницFlame Retardant Textiles For Electric Arc Flash Hazards: A ReviewTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 29 1645708157 2ijtftjun20222Документ8 страниц2 29 1645708157 2ijtftjun20222TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Baluchari As The Cultural Icon of West Bengal: Reminding The Glorious Heritage of IndiaДокумент14 страницBaluchari As The Cultural Icon of West Bengal: Reminding The Glorious Heritage of IndiaTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Development and Assessment of Appropriate Safety Playground Apparel For School Age Children in Rivers StateДокумент10 страницDevelopment and Assessment of Appropriate Safety Playground Apparel For School Age Children in Rivers StateTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Comparative Study of Original Paithani & Duplicate Paithani: Shubha MahajanДокумент8 страницComparative Study of Original Paithani & Duplicate Paithani: Shubha MahajanTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Using Nanoclay To Manufacture Engineered Wood Products-A ReviewДокумент14 страницUsing Nanoclay To Manufacture Engineered Wood Products-A ReviewTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 52 1649841354 2ijpslirjun20222Документ12 страниц2 52 1649841354 2ijpslirjun20222TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 4 1644229496 Ijrrdjun20221Документ10 страниц2 4 1644229496 Ijrrdjun20221TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 31 1648794068 1ijpptjun20221Документ8 страниц2 31 1648794068 1ijpptjun20221TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 52 1642055366 1ijpslirjun20221Документ4 страницы2 52 1642055366 1ijpslirjun20221TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Bolted-Flange Joint Using Finite Element MethodДокумент12 страницAnalysis of Bolted-Flange Joint Using Finite Element MethodTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- The Conundrum of India-China Relationship During Modi - Xi Jinping EraДокумент8 страницThe Conundrum of India-China Relationship During Modi - Xi Jinping EraTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 44 1653632649 1ijprjun20221Документ20 страниц2 44 1653632649 1ijprjun20221TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Effectiveness of Reflexology On Post-Operative Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic ReviewДокумент14 страницEffectiveness of Reflexology On Post-Operative Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic ReviewTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 51 1651909513 9ijmpsjun202209Документ8 страниц2 51 1651909513 9ijmpsjun202209TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 51 1656420123 1ijmpsdec20221Документ4 страницы2 51 1656420123 1ijmpsdec20221TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 51 1647598330 5ijmpsjun202205Документ10 страниц2 51 1647598330 5ijmpsjun202205TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- An Observational Study On-Management of Anemia in CKD Using Erythropoietin AlphaДокумент10 страницAn Observational Study On-Management of Anemia in CKD Using Erythropoietin AlphaTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Dr. Gollavilli Sirisha, Dr. M. Rajani Cartor & Dr. V. Venkata RamaiahДокумент12 страницDr. Gollavilli Sirisha, Dr. M. Rajani Cartor & Dr. V. Venkata RamaiahTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- A Review of "Swarna Tantram"-A Textbook On Alchemy (Lohavedha)Документ8 страницA Review of "Swarna Tantram"-A Textbook On Alchemy (Lohavedha)TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Vitamin D & Osteocalcin Levels in Children With Type 1 DM in Thi - Qar Province South of Iraq 2019Документ16 страницVitamin D & Osteocalcin Levels in Children With Type 1 DM in Thi - Qar Province South of Iraq 2019TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Effect of Degassing Pressure Casting On Hardness, Density and Tear Strength of Silicone Rubber RTV 497 and RTV 00A With 30% Talc ReinforcementДокумент8 страницEffect of Degassing Pressure Casting On Hardness, Density and Tear Strength of Silicone Rubber RTV 497 and RTV 00A With 30% Talc ReinforcementTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Covid-19: The Indian Healthcare Perspective: Meghna Mishra, Dr. Mamta Bansal & Mandeep NarangДокумент8 страницCovid-19: The Indian Healthcare Perspective: Meghna Mishra, Dr. Mamta Bansal & Mandeep NarangTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Self-Medication Prevalence and Related Factors Among Baccalaureate Nursing StudentsДокумент8 страницSelf-Medication Prevalence and Related Factors Among Baccalaureate Nursing StudentsTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 67 1648211383 1ijmperdapr202201Документ8 страниц2 67 1648211383 1ijmperdapr202201TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 67 1653022679 1ijmperdjun202201Документ12 страниц2 67 1653022679 1ijmperdjun202201TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Numerical Analysis of Intricate Aluminium Tube Al6061T4 Thickness Variation at Different Friction Coefficient and Internal Pressures During BendingДокумент18 страницNumerical Analysis of Intricate Aluminium Tube Al6061T4 Thickness Variation at Different Friction Coefficient and Internal Pressures During BendingTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 67 1645871199 9ijmperdfeb202209Документ8 страниц2 67 1645871199 9ijmperdfeb202209TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- 2 67 1645017386 8ijmperdfeb202208Документ6 страниц2 67 1645017386 8ijmperdfeb202208TJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- 2019 Brigada-Eskwela-Action-PlanДокумент7 страниц2019 Brigada-Eskwela-Action-PlanMercedita Balgos67% (3)

- New Batch Intake Application Form UCJДокумент4 страницыNew Batch Intake Application Form UCJsajeevclubОценок пока нет

- Research PaperДокумент40 страницResearch PaperBENEDICT FRANZ ALMERIAОценок пока нет

- Assessment of The Knowledge Attitude and PracticeДокумент7 страницAssessment of The Knowledge Attitude and PracticeAamirОценок пока нет

- The Praise of Twenty-One Taras PDFДокумент23 страницыThe Praise of Twenty-One Taras PDFlc099Оценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan in English 5Документ4 страницыLesson Plan in English 5Ivan MeguisoОценок пока нет

- 4024 Mathematics (Syllabus D) : MARK SCHEME For The May/June 2011 Question Paper For The Guidance of TeachersДокумент4 страницы4024 Mathematics (Syllabus D) : MARK SCHEME For The May/June 2011 Question Paper For The Guidance of TeachersAyra MujibОценок пока нет

- Miguel L. Rojas-Sotelo, PHD Cultural Maps, Networks and Flows: The History and Impact of The Havana Biennale 1984 To The PresentДокумент562 страницыMiguel L. Rojas-Sotelo, PHD Cultural Maps, Networks and Flows: The History and Impact of The Havana Biennale 1984 To The PresentIsobel Whitelegg100% (1)

- A Guide To The Linguistic and Stylistic Analysis of A Passage From ChaucerДокумент3 страницыA Guide To The Linguistic and Stylistic Analysis of A Passage From ChaucerNasrullah AliОценок пока нет

- Lawrence Nyakurimwa Induction Module 47227 (R2305D16579999)Документ5 страницLawrence Nyakurimwa Induction Module 47227 (R2305D16579999)Lawrence NyakurimwaОценок пока нет

- Kyle Dunford: Highlights of QualificationsДокумент1 страницаKyle Dunford: Highlights of Qualificationsapi-272662230Оценок пока нет

- Bài tập Vocabulary 13-14Документ4 страницыBài tập Vocabulary 13-14Vy Tran Thi TuongОценок пока нет

- CowellДокумент13 страницCowellapi-349364249Оценок пока нет

- Yoga The Iyengar WayДокумент194 страницыYoga The Iyengar WayAnastasia Pérez100% (9)

- Broadcasting WorkshopДокумент9 страницBroadcasting WorkshopRyan De la TorreОценок пока нет

- Case of BundocДокумент5 страницCase of Bundocjunar dacallosОценок пока нет

- Barringer-Chapter11 - Unique Marketing IssuesДокумент34 страницыBarringer-Chapter11 - Unique Marketing IssuesWazeeer AhmadОценок пока нет

- Individual Differences, 48, 926-934.: Piers - Steel@haskayne - UcalgaryДокумент44 страницыIndividual Differences, 48, 926-934.: Piers - Steel@haskayne - UcalgaryArden AriandaОценок пока нет

- Position Paper About James Soriano's ArticleДокумент2 страницыPosition Paper About James Soriano's ArticleAnah May100% (3)

- SHS CORE DIAL ME POST TEST CLASS CODEДокумент2 страницыSHS CORE DIAL ME POST TEST CLASS CODEEmmanuel Paul JimeneaОценок пока нет

- Government of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentДокумент2 страницыGovernment of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentzulnorainaliОценок пока нет

- EEE610 Presentation Chapter 4Документ31 страницаEEE610 Presentation Chapter 4FIK ZXSОценок пока нет

- Reaction Paper On Rewards and RecognitionДокумент8 страницReaction Paper On Rewards and RecognitionMashie Ricafranca100% (2)

- Dự Án Đề Thi Thử Tốt Nghiệp Thpt Qg 2021 - phân Loại Theo Dạng Bài - thầy Lương (Dr Salary)Документ68 страницDự Án Đề Thi Thử Tốt Nghiệp Thpt Qg 2021 - phân Loại Theo Dạng Bài - thầy Lương (Dr Salary)Thư MinhОценок пока нет

- Earth Science Syllabus PDFДокумент4 страницыEarth Science Syllabus PDFthanksforshopinОценок пока нет

- Initiative in Promoting World Heritage PreservationДокумент8 страницInitiative in Promoting World Heritage PreservationESPORTS HanaОценок пока нет

- Evidence-Based Treatment of Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder in A Preschool-Age Child: A Case StudyДокумент10 страницEvidence-Based Treatment of Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder in A Preschool-Age Child: A Case StudyCristinaОценок пока нет

- Why We Need Christopher Dawson PDFДокумент30 страницWhy We Need Christopher Dawson PDFCastanTNОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan 4 RC 18.7.2019Документ2 страницыLesson Plan 4 RC 18.7.2019AQILAH NASUHA BINTI ABDULLAH SANI MoeОценок пока нет

- CCS 301 Spring 2014 SyllabusДокумент8 страницCCS 301 Spring 2014 SyllabusSimone WrightОценок пока нет