Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Abdominal Tenderness in Ascites Patients Indicates

Загружено:

donkeyendutАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Abdominal Tenderness in Ascites Patients Indicates

Загружено:

donkeyendutАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

European Journal of Internal Medicine 18 (2007) 44 47

www.elsevier.com/locate/ejim

Original article

Abdominal tenderness in ascites patients indicates

spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Sven Wallerstedt a,, Rolf Olsson b , Magnus Simrn b , Ulrika Broom c , Staffan Wahlin c ,

Lars Lf d , Rolf Hultcrantz e , Klas Sjberg f , Hanna Sandberg Gertzn g ,

Hanne Prytz h , Sven Almer i

a

Department of Medicine, Sahlgrenska University Hospital/stra, SE-416 85, Gteborg, Sweden

b

Department of Medicine, Sahlgrenska University Hospital/Sahlgrenska, Gteborg, Sweden

c

Department of Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital/Huddinge, Huddinge, Sweden

d

Department of Medicine, Akademiska University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden

e

Department of Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital/Solna, Solna, Sweden

f

Department of Medicine, University Hospital MAS, Malm, Sweden

g

Department of Medicine, University Hospital, rebro, Sweden

h

Department of Medicine, University Hospital, Lund, Sweden

i

Department of Medicine, University Hospital, Linkping, Sweden

Received 13 February 2006; received in revised form 1 June 2006; accepted 11 July 2006

Abstract

Background: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), which has been reported to be present in 1030% of patients with cirrhotic ascites, may

easily be overlooked. An important aim of our study was to determine whether there are any clinical signs which, in clinical practice, may

predict or exclude SBP.

Methods: We studied 133 patients with cirrhotic ascites from medical units at nine Swedish university hospitals where there had been at least

one diagnostic ascites tap with analysis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the ascites fluid. The patients had initially been questioned about

background factors and physically examined according to a standardized case record form. Samples of blood, urine, and ascites were then

drawn for analysis according to a structured schedule.

Results: SBP could be excluded in 80% of all the cases and was confirmed in 8% of the 133 patients in the final analysis. Abdominal pain

and abdominal tenderness were more common in patients with SBP (p b 0.01), but no other physical sign or laboratory test could separate

SBP cases from the others.

Conclusions: SBP was present in about one-tenth of the hospitalized patients with cirrhotic ascites in this cohort. Performing repeated physical

examinations and paying particular attention to abdominal tenderness may be the best way to become aware of the possible development of this

complication.

2006 European Federation of Internal Medicine. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Cirrhosis; Diagnosis; Signs; Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; Symptoms

1. Introduction

Although spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is an

important complication of cirrhotic ascites, having been

estimated to be present in 1030% of cases [1], its prevalence

Corresponding author. Tel.: +46 31 3434000; fax: +46 31 259254.

E-mail address: sven.wallerstedt@medic.gu.se (S. Wallerstedt).

and clinical picture are somewhat obscure. There are several

explanations for this, due to changes in the diagnostic criteria

that have been established for SBP in the years since this

clinical entity was first described in 1964 [2]. At that time,

cultures positive for ascites and blood were obligatory for the

diagnosis. Two decades later, Runyon and Hoefs described an

ascites culture-negative variant of SBP [3]. One reason for a

negative ascites culture could be the low bacterial content in

0953-6205/$ - see front matter 2006 European Federation of Internal Medicine. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2006.07.022

S. Wallerstedt et al. / European Journal of Internal Medicine 18 (2007) 4447

SBP ascites, i.e., one to two organisms per mL [4], which, to

some extent, can be overcome using a blood culture technique

[1]. Nowadays, a positive ascites culture is not mandatory for

the diagnosis of SBP, which is defined as neutrocytic ascites

with at least 0.250 109 polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN)

per liter in the absence of an abdominal infectious focus [1].

Thus, the diagnosis may be overlooked if abdominal paracentesis and analysis of ascites are not performed. In the past,

paracentesis was generally restricted to severely ill patients

because of an unfounded fear of complications [5]. In these

patients, the prevalence of SBP was thought to be high. The

modern practice of paracentesis, also in less diseased patients,

should result in a lower frequency of SBP. This idea is

supported by the finding of SBP in 3.5% of 427 asymptomatic

cases among 513 outpatients with cirrhotic ascites who underwent paracentesis [6].

Various predisposing factors, clinical signs, and prognostic

markers for SBP development have been studied. Analyses of

factors that are associated with SBP have generally shown that

the parameters included in the ChildPugh classification [7],

albumin, coagulation factors (prothrombin complex), bilirubin,

and encephalopathy are the most important. In 1986, Runyon

concluded that there was an inverse relation between the

protein content in ascites and susceptibility to infections [8].

This is supported, for example, by the finding that a protein

concentration in ascites of less than 10 g/L is common in SBP,

whereas carcinomatosis-related ascites with a high protein

content very seldom becomes infected.

One aim of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence

of SBP in Swedish hospitalized patients with cirrhotic ascites.

Based on our clinical experience, we hypothesized that SBP in

modern clinical practice should be infrequent. Another aim

was to study to what extent clinical and laboratory data could,

in clinical practice, predict or exclude the presence of SBP in

these patients.

2. Materials and methods

Patients with a diagnosis of cirrhotic ascites and with an

analysis of ascites leukocyte count, but without secondary

peritonitis, were prospectively included in the study. Most of

these patients had been hospitalized because of ascites. Only

the first ascites episode during the study period was registered.

Initially, 156 patients were included in the study, but two

patients were later excluded since the ascites was bloody and

no correction [9] had been performed to compensate for added

blood leukocytes. Another 21 cases had to be excluded because no differential leukocyte count had been performed,

although the ascites leukocyte count was at least 0.250 109/L.

For the final analysis, 133 patients were available, and they

were divided into two groups. The first (non-SBP) group

consisted of patients with a leukocyte or PMN count in ascites

below 0.250 109/L. The second (SBP) group consisted of

patients with an ascites PMN count of at least 0.250 109/L.

All patients were questioned about background factors

and physically examined according to a standardized form

45

(Table 1) before the ascites tap. The ascites volume was

determined as the fluid volume received by total paracentesis

with complete ascites mobilization as the goal (maximum 21 L

in a non-SBP patient). The results of routine analyses of blood,

serum, ascites, and urine were also recorded in accordance

with a structured schedule (Table 2), and the patients were then

classified according to their ChildPugh classification [7].

Body mass index (BMI), calculated after ascites mobilization,

was used to reflect malnutrition. The local ethics committees

approved the study.

For the statistical analysis of possible differences between

SBP and non-SBP cases with regard to background factors,

symptoms, physical findings, and laboratory results, we used

Fisher's non-parametric permutation test [10]. A p-value

below 0.05 was regarded as significant.

3. Results

SBP could be excluded in 123 of the original cohort of 154

patients (80%). A positive SBP diagnosis was established in

10 of the 133 patients included in the final analysis (7.5%). A

positive bacterial ascites culture was found in two of these ten

patients (Escherichia coli and alpha streptococci, respectively). In two of the eight culture-negative cases, antibiotics had

been given before the paracentesis.

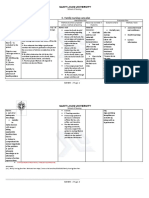

Table 1

Clinical data on 133 patients with and without SBP

Age (years)

Sex [male:female] (n)

SBP

(n = 10)

non-SBP

(n = 123)

61

8:2

58

86:37

Background history

SBP, earlier (n)

Alcohol etiology (n)

Hepatitis C antibodies (n)

Antibiotics due to any infection in

last 6 months (n)

Cortisone treatment (n)

Immunosuppressive treatment (n)

Portosystemic encephalopathy, earlier (n)

Variceal bleeding (n)

Variceal sclerotherapy (n)

0

6

4 (9)

3

9 (119)

84

25 (114)

40 (121)

1

0

2

3

2

7

4 (122)

26

30 (117)

28 (115)

Present case history

Alcohol intake last week (n)

Respiratory infection (n)

Abdominal pain (n)

Intravenous therapy (n)

Days at hospital before puncture (median, n)

2

1

8

6

2.0 (8)

37

7

36 (121)

61 (121)

4.0 (50)

Physical findings

Body mass index [(weight in kg)/(length in m)2]

ChildPugh-class [A:B:C] (n)

Spiders 3 (n)

Fever (n)

38.0 C (n)

Abdominal tenderness (n)

Portosystemic encephalopathy (n)

25.4 (8)

0:3:7

6

4

1

7

2

23.5 (85)

0:25:98

59 (115)

29 (119)

7

28 (120)

22 (119)

In cases of missing data, the number of patients is given within parentheses.

46

S. Wallerstedt et al. / European Journal of Internal Medicine 18 (2007) 4447

Table 2

Laboratory tests (mean values with confidence intervals within parentheses)

in 133 patients with and without SBP

B-hemoglobin (g/L)

B-leukocyte count (109/L)

B-platelet count (109/L)

S-AST (kat/L)

S-ALT (kat/L)

S-alkaline phosphatases (kat/L)

S-bilirubin (mol/L)

Prothrombin complex (INR)

S-sodium (mmol/L)

S-potassium (mmol/L)

S-creatinine (mol/L)

S-albumin (g/L)

S-immunoglobulin G (g/L)

Ascites-volume (L)

Ascites-protein (g/L)

Ascites-albumin (g/L)

Ascites-amylase (kat/L)

U-sodium (mmol/L)

U-potassium (mmol/L)

1

SBP

(n = 10)

non SBP

(n = 123)

116 (102131)

11.5 (5.817.2)

164 (98230)

4.61 (011.06)

1.92 (03.95)

13.3 (3.323.3)

140 (68212)

1.4 (1.191.70)4

132 (128136)

4.2 (3.64.8)

157 (92222)

26 (2231)4

16 (1221)2

5.5 (2.28.9)1

17 (726)2

10 (416)3

0.6 (01.3)1

31 (657)1

37 (1361)1

114 (110117)

10.5 (9.411.7)12

183 (164202)

1.92 (1.562.28)12

1.24 (0.432.04)12

8.8 (7.89.8)12

112 (88136)12

1.5 (1.461.59)12

133 (132134)

4.0 (3.84.1)

124 (106142)12

24 (2325)11

17 (1518)10

6.7 (5.57.9)5

13 (1115)8

8 (510)9

0.6 (0.40.7)6

65 (5476)7

33 (2938)7

n = 5, 2n = 6, 3n = 8, 4n = 9, 5n = 59, 6n = 65, 7n = 71, 8n = 72, 9n = 90, 10n = 96,

n = 115, 12n = 122. B, blood; S, serum; U, urine.

11

There were few clinical differences between the two groups

(Table 1). Complaints of abdominal pain, as well as the presence of abdominal tenderness, were, however, more common

in SBP than in non-SBP patients (80% vs. 30%, p = 0.0050,

and 70% vs. 23%, p = 0.0079, respectively). With regard to

abdominal tenderness as a possible sign of SBP, the positive

predictive value was 20% (7/35) and the negative predictive

value 97% (92/95).

None of the SBP patients had had an earlier SBP episode,

whereas this was reported in the files of 9 of the 119 non-SBP

cases. The time period between admission and paracentesis

was similar in the two groups. Signs of liver dysfunction,

malnutrition, the presence of an alcohol or hepatitis C viral

etiology, immune-modulating therapy, suspicion of a susceptibility to infections, esophageal varices, and intravenous

catheterization were not more common in the SBP group. The

results from laboratory tests did not differ between the two

groups (Table 2).

4. Discussion

We found that SBP, as a complication of cirrhotic ascites,

was less frequent than what has generally been published to

date [1]. Although some of the local laboratories did not

perform a PMN count in cases with an ascites leukocyte

count below 0.500 109/L, SBP could be excluded in more

than 80% of the cases since at least the total leukocyte count

was below 0.250 109/L. Thus, the occurrence of SBP in

7.5% of our cases might have been higher if this complication had been present in some of the excluded cases. On

the other hand, our figure may be too high since the high

prevalence of abdominal tenderness in our cohort, 27%, could

reflect readiness for paracentesis, especially in such cases

where SBP is common. Furthermore, our clinical impression

is that there is a substantial number of patients with cirrhotic

ascites who do not undergo a diagnostic paracentesis.

A problem when comparing various prevalence studies is

the use of different diagnostic criteria. For example, in a

well-performed Danish study from 1987 [11], 4 out of 13

patients with SBP would nowadays have been classified as

having bacterial ascites [1,4] rather than SBP, reducing the

reported SBP prevalence from 19% to 13%. Other factors,

such as geographical differences, may explain the rather high

SBP prevalence of 23.7% in a recent Slovakian study, although an old disease definition, i.e., a PMN count of at least

0.500 109/L, was used in that study [12]. This reported prevalence figure would have been even higher if the modern

definition had been used.

Several studies have been performed to reveal factors predisposing to SBP. Andreu et al. [13] found that a prothrombin

complex greater than 1.2 (INR), a serum albumin below 27 g/L,

and a serum bilirubin above 42.7 mol/L had prognostic significance. The two last parameters could be used in a formula to

calculate the relative risk of a first SBP. The three parameters

mentioned are also components of the formula used for the

modified ChildPugh classification [7]. Thus, it is not surprising that ChildPugh class C has been reported to be a risk

factor for SBP [5]. As is apparent from our study, there is a great

overlap in these factors between cases with and without SBP.

This is also apparent with other reported risk factors, such as

protein content in ascites below 10 g/L, a history of variceal

bleeding, or an earlier SBP episode [5].

Although SBP may be asymptomatic, this complication

must be considered if a patient with cirrhotic ascites develops

symptoms or signs of local and/or systemic infection or an

unexplained clinical deterioration. Many clinical signs have

been studied, but in our study abdominal tenderness, present

in 70%, was the only one that was strongly related to SBP.

This is consistent with what has been reported by Runyon,

who claimed that 3944% of patients with a diagnosis of

SBP showed this physical sign [14]. Abdominal tenderness

was, along with jaundice, the most prominent physical sign,

54.5%, in a recent study of symptomatic SBP cases [15].

Also, other symptoms and signs, such as abdominal pain,

clinically relevant alterations of gastrointestinal motility,

fever, mental deterioration, and renal impairment, may reflect the development of SBP [1].

Irrespective of the reported SBP risk factors, paracentesis

should be performed in every hospitalized patient with cirrhotic

ascites. This is also true for patients admitted for reasons other

than ascites. It is important to get a PMN count in order to initiate

antibiotic treatment and to use an adequate culture technique [1].

According to our results, repeated paracentesis must be considered for patients developing abdominal pain and/or abdominal tenderness, even though a minority of these patients have

SBP. On the other hand, the absence of abdominal tenderness

very strongly contradicts the presence of this complication, not

only in outpatients [6] but also in hospitalized patients.

S. Wallerstedt et al. / European Journal of Internal Medicine 18 (2007) 4447

In conclusion, our study indicates that performing repeated

clinical examinations of patients with cirrhotic ascites, paying

particular attention to abdominal tenderness, is essential in

deciding whether diagnostic paracentesis should be carried out

to reveal possible SBP.

5. Learning points

Although infrequent, SBP should be considered in cirrhotic

patients with ascites and abdominal tenderness.

The absence of abdominal tenderness, on the other hand,

strongly contradicts SBP.

Acknowledgements

The study was initiated by SILK, the Swedish Internal

Medicine Liver Club, which is supported by Meda. We also

thank Anders Odn, PhD, for the statistical analyses.

References

[1] Rimola A, Garcia-Tsao G, Navasa M, Piddock LJV, Planas R, Bernard

B, et al, and the International Ascites Club. Diagnosis, treatment and

prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. J Hepatol 2000;32:14253.

[2] Conn HO. Spontaneous peritonitis and bacteremia in Laennec's

cirrhosis caused by enteric organisms. A relatively common but rarely

recognized syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1964;60:56880.

47

[3] Runyon BA, Hoefs JC. Culture-negative neutrocytic ascites: a variant

of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology 1984;4:120911.

[4] Bhuva M, Ganger D, Jensen D. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: an update

on evaluation, management, and prevention. Am J Med 1994;97:16975.

[5] Such J, Runyon BA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Infect Dis

1998;27:66976.

[6] Evans LT, Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Kamath PS. Spontaneous bacterial

peritonitis in asymptomatic outpatients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology 2003;37:897901.

[7] Albers I, Hartmann H, Bircher J, Creutzfeldt W. Superiority of the Child

Pugh classification to quantitative liver function tests for assessing

prognosis of liver cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol 1989;24:26976.

[8] Runyon BA. Low-protein-concentration ascitic fluid is predisposed to

spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1986;91:13436.

[9] Hoefs JC. Increase in ascites white blood cell and protein concentrations during diuresis in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology

1981;1:24954.

[10] Good P. Permutation tests. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000.

[11] Almdal TP, Skinhoej P. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis.

Scand J Gastroenterol 1987;22:295300.

[12] Jarcuska P, Veseliny E, Orolin M, Takacova V, Hancova M.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in the patients with liver cirrhosis.

Klin Mikrobiol Infekc Lek 2004;10:26570.

[13] Andreu M, Sola R, Sitges-Serra A, Alia C, Gallen M, Vila MC, et al.

Risk factors for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients

with ascites. Gastroenterology 1993;104:11338.

[14] Runyon BA. Ascites. In: Schiff L, Schiff ER, editors. Diseases of the Liver.

7th edition. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company; 1993. p. 9901015.

[15] Filik L, Unal S. Clinical and laboratory features of spontaneous

bacterial peritonitis. East Afr Med J 2004;81:4749.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Sparks and Taylor's Nursing Diagnosis Pocket GuideДокумент514 страницSparks and Taylor's Nursing Diagnosis Pocket GuideShawnPoirier100% (13)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- OSCE Checklist: Thyroid Status ExaminationДокумент2 страницыOSCE Checklist: Thyroid Status ExaminationNur Farhana Athirah Azhari100% (2)

- Test BДокумент11 страницTest BMaria HillОценок пока нет

- 123456789-Lectures On Homoeopathic Philosophy by JT Kent-123456789Документ181 страница123456789-Lectures On Homoeopathic Philosophy by JT Kent-123456789fapatel95Оценок пока нет

- Nursing Health HistoryДокумент11 страницNursing Health Historyrubycorazon_edizaОценок пока нет

- Edison College Nursing Program Infection Risk PlanДокумент3 страницыEdison College Nursing Program Infection Risk PlanBrian Bracher93% (43)

- C. Family Nursing Care Plan: Saint Louis UniversityДокумент2 страницыC. Family Nursing Care Plan: Saint Louis UniversityLEONELLGABRIEL RAGUINDIN0% (1)

- OSCE ManualДокумент40 страницOSCE Manualdkasis100% (1)

- Nursing Care Plan for Respiratory IssuesДокумент10 страницNursing Care Plan for Respiratory IssuesMykel Jake VasquezОценок пока нет

- Wrist Sizing HamiltonДокумент3 страницыWrist Sizing HamiltondonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Wrist Sizing Hamilton PDFДокумент3 страницыWrist Sizing Hamilton PDFdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Ap 1 PDFДокумент7 страницAp 1 PDFdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Analisa Dan Penanganan Hepatitis Kemenkes RIДокумент8 страницAnalisa Dan Penanganan Hepatitis Kemenkes RIIzzi FekratОценок пока нет

- Dep 1 PDFДокумент11 страницDep 1 PDFdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Standardized Mini-Mental State Exam GuideДокумент2 страницыStandardized Mini-Mental State Exam GuideSummer WrightОценок пока нет

- Mekanisme Aksi DopaminДокумент14 страницMekanisme Aksi DopamindonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Dopamin 2 PDFДокумент8 страницDopamin 2 PDFdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Gold WR 06Документ100 страницGold WR 06Melissa VidalesОценок пока нет

- Fatique and Artritis Psoriatic PDFДокумент72 страницыFatique and Artritis Psoriatic PDFdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Depression Theory PDFДокумент2 страницыDepression Theory PDFdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Looking Beyond The Monoamine Hypothesis: Johan A Den BoerДокумент9 страницLooking Beyond The Monoamine Hypothesis: Johan A Den BoerdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- HHLДокумент7 страницHHLdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Geriatri Editorial - Dementia.npsДокумент5 страницJurnal Geriatri Editorial - Dementia.npsdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- How To Measure Cd14Документ38 страницHow To Measure Cd14donkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Summary Sepsis ManagementДокумент60 страницSummary Sepsis ManagementdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Tabel Dan Grafik Psiko ACPM 2014Документ1 страницаTabel Dan Grafik Psiko ACPM 2014donkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Turgor KulitДокумент21 страницаTurgor KulitChairunisa AnggrainiОценок пока нет

- Tesis Lampiran 9Документ5 страницTesis Lampiran 9donkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Geriatri Eur Geriatr Med 2015Документ6 страницJurnal Geriatri Eur Geriatr Med 2015donkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Geriatri Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014Документ9 страницJurnal Geriatri Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014donkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Jurnal 1 Impaired Tcell in HIVДокумент9 страницJurnal 1 Impaired Tcell in HIVdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Occupational Asthma Occupational Asthma: Sri Handayani LubisДокумент19 страницOccupational Asthma Occupational Asthma: Sri Handayani LubisdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Tesis Lampiran Tabel Induk RevisiДокумент1 страницаTesis Lampiran Tabel Induk RevisidonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Jurnal 11 CD Manual Anthrax May2012Документ4 страницыJurnal 11 CD Manual Anthrax May2012donkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Dr. Hendra Ajbr0001-0175Документ15 страницDr. Hendra Ajbr0001-0175donkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Baru Anthrax - Protocol PDFДокумент13 страницBaru Anthrax - Protocol PDFdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Nakamura 2008 Critical CareДокумент2 страницыNakamura 2008 Critical CaredonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Infliximab (Remicade) in The Treatment of Psoriatic ArthritisДокумент12 страницInfliximab (Remicade) in The Treatment of Psoriatic ArthritisdonkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Ap 1Документ7 страницAp 1donkeyendutОценок пока нет

- Wound Essentials 5 Investigating Wound InfectionДокумент5 страницWound Essentials 5 Investigating Wound Infectionyash agarwalОценок пока нет

- Peads Teacher MannualДокумент108 страницPeads Teacher MannualMobin Ur Rehman KhanОценок пока нет

- Pre-Op Deep BreathingДокумент8 страницPre-Op Deep BreathingEmmanuel BeresoОценок пока нет

- Nursing Care Plan for Post-Surgical ClientДокумент5 страницNursing Care Plan for Post-Surgical ClientQueen Shine0% (1)

- Format of Case Study-121Документ4 страницыFormat of Case Study-121Shaina OturdoОценок пока нет

- Heyer Vizor Cs - Manual 1.0 enДокумент68 страницHeyer Vizor Cs - Manual 1.0 enkalandorka92Оценок пока нет

- Neonatal Pneumonia in Rural Bangladesh: Prevalence, Clinical Features and OutcomesДокумент5 страницNeonatal Pneumonia in Rural Bangladesh: Prevalence, Clinical Features and Outcomesmirashabrina12Оценок пока нет

- Patient Care Conference: Small Group Teaching MethodДокумент3 страницыPatient Care Conference: Small Group Teaching MethodValarmathiОценок пока нет

- Pneumosinus Dilatans Frontalis: A Case ReportДокумент5 страницPneumosinus Dilatans Frontalis: A Case ReportInternational Medical PublisherОценок пока нет

- NCPДокумент17 страницNCPShayne Jessemae AlmarioОценок пока нет

- Case Study CholelithiasisДокумент2 страницыCase Study CholelithiasisJes SarylОценок пока нет

- 664717ku PDFДокумент19 страниц664717ku PDFShankar Sex boyОценок пока нет

- Clinical Evidence for Diagnosing Chronic Heart FailureДокумент209 страницClinical Evidence for Diagnosing Chronic Heart Failurerahma watiОценок пока нет

- Performance of Clinical Signs in Diagnosing DehydrationДокумент13 страницPerformance of Clinical Signs in Diagnosing DehydrationAncuk RaimuОценок пока нет

- Signs and Symptoms of Pancreatic Cancer Fact Sheet Dec 2014Документ6 страницSigns and Symptoms of Pancreatic Cancer Fact Sheet Dec 2014Nus EuОценок пока нет

- Nursing Case StudyДокумент10 страницNursing Case StudyAriel Vincent G. YeeОценок пока нет

- Nutrition Intervention Case StudiesДокумент8 страницNutrition Intervention Case StudiesSammy OhОценок пока нет

- Compiled DocumentДокумент261 страницаCompiled DocumentAbhigyan Kishor100% (1)

- Casumpang V CortejoДокумент12 страницCasumpang V CortejoMariel CabubunganОценок пока нет

- Solving Safety Implications in A Case Based Decision-Support System in MedicineДокумент81 страницаSolving Safety Implications in A Case Based Decision-Support System in MedicineClo SerОценок пока нет

- Reflective Writing #1 First Week in Clinical PlacementДокумент1 страницаReflective Writing #1 First Week in Clinical PlacementShrests SinhaОценок пока нет