Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Lived Experience of Mothers of Children With Chronic Feeding and

Загружено:

AlgutcaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Lived Experience of Mothers of Children With Chronic Feeding and

Загружено:

AlgutcaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Dysphagia (2009) 24:322-332

DOI 100.1007/s00455-009-9210-7

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The Lived Experience of Mothers of Children with Chronic Feeding and/or

Swallowing Difficulties

Ronelle Hewetson - Shajila Singh

Published online: 4 March 2009

Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009

Abstract

The purpose of this phenomenologic

study was to describe the lived experiences of seven

mothers who were providing home-based care for their

children with feeding and/or swallowing difficulties. Data

were collected using semistructured interviews and were

analyzed as per Colaizzis method of inductive reduction.

Results suggest that the mothers experiences can be

understood as two continuing journeys that were not

mutually exclusive. The first, Deconstruction: A journey of

loss and disempowerment, comprised three essences: (1)

losing the mother dream, (2) everything changes: living life

on the margins, and (3) disempowered: from mother to

onlooker. The second journey was Reconstruction: Getting

through the brokenness with the essences of (4) letting go

of the dream and valuing the real, (5) self-empowered:

becoming the enabler, (6) facilitating the journey, and (7)

the continuing journey: negotiating balance.

Keywords Caregiver experiences Feeding and/or

swallowing difficulties Post-traumatic growth

Deglutition disorders

R. Hewetson - S. Singh

Division of Communication Sciences. University of Cape Town,

Observatory, Cape Town 7925, South Africa

Email: ronelle.hewetson@uct.ac.za; rhewetson@gmail.com

A pediatric feeding and/or swallowing difficulty is serious

and potentially fatal as it can lead to the development of

complications such as growth failure and chronic lung

disease [1]. Many of these difficulties may be resolved with

medical treatment, except in about 3% of cases which will

be chronic in nature and require intensive intervention and

hospitalization [2]. Chronic feeding and/or swallowing

difficulties make it a challenge or impossible for children to

obtain adequate nutrition through oral intake alone

necessitating enteral feeding [3]. The use of enteral feeding

to manage short-term and chronic feeding difficulties is

increasingly recommended, which means that more mothers

are expected to manage this technology at home [3].

Most of the available literature on chronic feeding

and/or swallowing difficulties, according to Craig et al. [4],

adopts a biomedical emphasis on factors such as weight

gain and reduction in the incidence of feeding-related

medical complications. Relatively few international studies

[4-7] and one in South Africa [8] have examined the

everyday experiences of caring for a child with chronic

feeding difficulties, and little information is available on

factors that enable or hinder a mothers capacity to provide

such care. Mothers and other caregivers may feel

unprepared for the demands of caring for a child who

requires adapted feeding strategies [5, 9, 10]. Mealtimes are

described as difficult. Parents describe ambivalent feelings

about oral as opposed to enteral feeding [9]. Inconsistent

advice and techniques taught by professionals, together

with the manner in which information is provided, were

identified as sources of stress [7, 11]. Women often frame

their difficulty in performing feeding tasks as personal

inadequacies based on cultural and moral constructs about

motherhood, which is closely linked to the concept of the

ideal or good mother, defined by Woodward [12], as

the supposed transformation of women into the ideal

mother as a natural consequence of pregnancy. When the

ideal of meeting a childs feeding needs with ease is

unattainable, a perception of inadequacy may arise [13].

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

Though only a small number of studies have evaluated

parental experiences of managing enteral feeding at home,

what emerged was that it was often associated with

caregiver burden, perceptions of loss, and a greater degree

of stress was experienced relative to that of mothers with

children who had disabilities but who could still be fed

orally [3, 5, 14]. The initial decision to have a gastrostomy

tube inserted was found to be difficult for mothers to make,

which was not necessarily made easier where oral feeding

was challenging [4]. A link between a mothers perception

that she failed in her ability to feed her child orally and the

struggle to agree to have a gastrostomy tube insertion has

been identified [14]. The extent to which a chronic feeding

difficulty can impact on the primary feeders life was

explored by Franklin and Rodger [6] who reported that the

resultant changes to daily routines presented potential

physical and emotional consequences for the whole family

[6]. However, the benefits of providing home-based care

[15-17] to a family member who requires assistance with

daily needs has also been found to have the potential to

enrich and enhance the quality of life of those who provide

such care.

Research on experience of feeding has been

conducted primarily in Australia , North America, and

United Kingdom [4-7,9].South Africa potentially provides

a very different developing nation context in which

mothers are accessing healthcare services and providing

home-based care for children with chronic feeding

difficulties, thus highlighting the need for a study to be

conducted in Cape Town. The findings will have

implications for speech language pathologist, who are

uniquely concerned whit the management of feeding

disorders [18] . The aim of this study was therefore to add

to the understanding of the factors that enhance or hinder a

mothers ability to provide home-based care for her child

with chronic feeding difficulties, thus guiding healthcare

professionals in supporting families and promoting optimal

child outcomes.

Research Design and Method

The study aimed to broaden understanding of a group of

mothers experiences in the context of caring for a child

with chronic feeding and/or swallowing difficulties at

home and in accessing public healthcare services for what

child in Cape Town, South Africa. In order to describe the

essence of being such a mother, a phenomenologic

approach was chosen as the most appropriate design.

Phenomenology is a qualitative research that provides an

in-depth description of how people experience a give

phenomenon and ascribe meaning to their experiences

[19]. The field of speech-language pathology is guided by

evidence-based practice to demonstrate efficacy of

management. The importance of contextual considerations

cannot be ignored. Evidence is incomplete unless

information about complex phenomena such as human

behavior is reported. Evidence can be gained by

considering the lived experiences of participants [20]. As

such, a qualitative study has the potential to make

contributions to evidence-based practice [21].

Aims

The aims of this study were to describe a group of mothers

experiences in addressing the feeding needs of their

children; explore how these feeding mothers defined their

role and identity as a mother; and report barriers to and

enablers of capacity to provide home-based care and to

access health care services.

Participants

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Cape

Towns faculty of Health Science Research Ethics

Committee. Purposeful sampling was used to select seven

women considered to be information-rich or who met the

inclusion criteria of providing home-based care for their

children with chronic feeding and/or swallowing

difficulties. The sample size in this study was based on the

minimum sampling strategy recommended by Patton [22]

in which the sample size is typically small as the aim is to

obtain richness and depth of information.

The participants all resided in and accessed public

healthcare services in Cape Town, South Africa. They were

diverse in their ages (between 22 and 45 years of age),

employment status, and marital status. At the time of the

study one mother had recently returned to full-time

employment, three were in part-time positions, and three

were unemployed. Five of the mothers were married (four

lived with their spouse) and were single. Their children

ranged in age from 3 to 13 years, with a mean age of 6

years 8 months. There was also variability with regard to

the onset (birth, infancy, and late childhood) and the nature

of the childrens feeding difficulties, as well as the type of

adapted feeding strategies used (children received

exclusive oral feeding, four exclusive enteral feeding).

Though the participants were not homogeneous, they were

all mothers who provided home-based care for their

children with chronic feeding difficulties.

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

Data Collection Procedures

Each of the mothers in this study participated in an indepth semistructured

interview [23].the general

interview guide approach [22] was used, which allowed

flexible exploration of issues raised by the mothers during

the interviews. This approach provided them with the

space to tell their stories without the influence of the

researchers personal assumptions. Suspension or

bracketing of the researchers assumptions, as required in

phenomenologic research, was implemented to reduce

interviewer bias and to enable a fuller understating of the

participants subjective experiences of the phenomenon

[24]. In an attempt to generate thick descriptions of the

phenomenon, detail and depth were gained through the

use of a main question and probe or follow-up questions

[23]. Each interview was initiated by asking the main

question: Please tell me as fully as you can about your

experiences of being the mother of a child with chronic

feeding difficulties. In answering this question think

about the things that have played a part in how you

experience your role as the mother. A preliminary

analysis of each interview enabled the researchers to

identify themes that in turn influenced questioning in

subsequent interviews. This flexibility reflected an

iterative process in line with the emergent design adopted

by this study. The audio-recorded interviews were

transcribed and a summary of emerging themes was then

returned to the participants to allow them to verify and

expand on their stories.

Data Analysis Procedures

The data analysis process was an adaptation of Colaizzis

[25] seven steps to analyzing data influenced by Giorgi

[26}, who emphasizes reduction of data in order to search

for essences common to all participants experiences. The

data analysis was inductive [27] as it occurred

concurrently with data collection and involved multiple

readings themselves in the data to facilitate intimate

familiarity with the content of each interview [28}.

Significant statements or units of information that were

directly related to the research question were selected and

arranged into themes. Clusters of themes emerged and

were directly and were grouped in seven essences.

Trustworthiness was addressed by describing the

phenomenon in a manner that captured the essence [26].

This study was designed and conducted to allow for an

audit trail [28] through which the dependability of the

findings could be evaluated. Credibility was enhanced

through the use of triangulation, member checking, and a

multiple-coding analysis strategy in which ten

independent coders interpreted segments of data.

Result

In describing the experiences of being the mother of a

child with chronic feeding and/or swallowing difficulties,

there emerged a need to present the data in two separate

categories representing two separate journeys. The two

categories stand apart as there is not a linear relationship

in terms of moving away from the experiences outlined in

"Deconstruction: A journey of loss and disempowerment"

toward those discussed in "Reconstruction: Getting

through the brokenness." Seven essences central to the

mothers experience emerged. A summary of the essences

within the two categories, together with the subthemes

that make up each essence, is provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Discussion

Verbatim quotes are used to delineate the mothers

experiences from the researchers discussion and the

academic literature. In order to preserve the essence of

their experiences, the discussion. By reviewing the

mothers words together with the associated meanings,

the reader is able to evaluate the trustworthiness of the

study.

Deconstruction: A Journey of Loss and Disempowerment

For the women who participated in this study, being the

mother of a child with chronic feeding and/or swallowing

difficulties meant starting a journey filled with emotional

and practical challenges. The term "deconstruction" was

chosen as a loss of role clarity, perceptions of competence

as mothers and social participation emerged.

Deconstruction was a universal process, characteristic of

the phenomenon that brought together experiences of loss

and disempowerment.

Losing the Mother Dream

One part of being the mother of a child with chronic

feeding difficulties meant that the mothers had to make

sense of societal, professional, and personally held

perceptions and beliefs about the link between the

mothering role and the ability to feed a child. The

incongruence between expectation and reality was most

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

strikingly experienced in the inability to feed but also in

having to perform uncomfortable or painful tasks on their

children, transforming their role from that of mother to

nurse. "... I can see that it is sore and uncomfortable for

him when I am doing it (reinserting the gastrostomy

tube), but I make myself hard because I know it has to be

done." The mothers' perception of their inability to

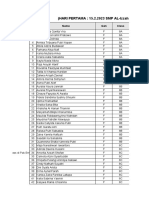

Table 1 Deconstruction: a journey of loss and disempowerment

Essence I

Losing the mother

dream

Essences 2

Everything

changes: living life

on the margins

Essence 3

Disempowered:

from mother to

onlooker

Subthemes

Significant statements (quotations from interviews)

Motherhood ideal and conflicting reality

A mother should naturally be able to feed her child, thats what mothers do

Bonding versus task

I tried to make the ask of putting milk through a tube as personal as what I

could, so I held him and talked to him

Questioning competence

For me the breastfeeding thing was I should at least be able to do it

Not letting go of the dream

Initially I was resistant to the idea [to enteral feeding] because it sort of felt like

that was the end you know

Changes to family interactions

I will sit on one side and feed her while the others are sitting eating somewhere

else having their Sunday lunch

Changes to lifestyle

If my husband says lets go to the beach I will say fine, but will go in my own

car so that I can come home to feed her

Changes in employment status and o

future plans

We havent been away since she was born. Our concern is for the future

Expected versus enable to cope

You are expected to do a lot things that I think most people would not be able to

cope with. Everybody expects that you must be able to do it because you are the

mother

I think the Physio sensed hope in me and thought: I'll sort out this hope. Every

day she would say: Do you realize how seriously disabled Rose (not actual

name) is? I'd get in the car and just cry

You just go for a check-up and that's it, you get no support from the hospital.

Your questions are never answered

Disempowering

interactions

professional

Disempowering public health system

Unanswered questions and unmet needs

identify with the construct of an ideal mother because a

good mother is a mother who is able tomake sure that

her children get enough food was closely related to a

theme of Maternal Failure identified by Thorne et al.

[3]. The participants in their study identified feeding as a

quintessential mothering act, symbolizing the loving role

associated with being a mother. In addition, a universal,

strong feeling of loss of their ideals of motherhood, which

extended further to the loss of the opportunity to bond with

their children, was present. For most of the mothers,

feeding became a tiring emotional capacity to accept the

loss of what they had expected to be bonding opportunity.

The loss of oral feeding and the need for adapted feeding

strategies resulted in them questioning their competence as

mothers. The experience of loss of an ideal about what

motherhood should be like was experienced by the mothers

in this study irrespective of the time of onset of feeding

difficulties.

The current study found a trend in an ongoing experience

of losing the mother dream, as the mothers recalled and

experience repeated and persistent grief and loss. A

persistent feeling of loss, described as chronic sorrow by

Olshansky [29], was not resolvable as the mothers in this

study could not let go of the dream and experienced

periodic resurgence of intense grief at times when they saw

other women performing mothering tasks relating feeding,

when their child was unable to participate in pleasurable

activities and social engagements involving eating (e.g.,

birthday parties, picnics, religious holidays), and when

expected developmental feeding milestones could not be

met: The presence of a persistent sorrow has also been

documented in parents of children with intellectual

impairment [30], Down syndrome [33], chronic mental

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

illness [34], and chronic medical conditions [35, 36] and

should be viewed as a natural rather than pathologic

reaction to ongoing experiences of loss in the presence of

chronic illness or disability [37]. Moreover, these parents

Essence 4

Letting go of the

dream

and

valuing the real

Essences 5

Self-empowered

becoming

the

enabler

Essence 6

Facilitating

journey

the

Subthemes

Significant statements

Redefining mother

You stop being a mother and you stop mothering in the traditional sense,

you become a caregiver

Celebrating the positives

When I say it so well done that she coughs so nicely, people look at me

and ask: She coughs well? But for me its such a big thing

Finding

support

information

Acquiring skills

The kind of information you need has to come from people, people who

have worked with these type of kid. You have to ask and people have to

tell you

I mean, there are a lot of things that I learnt. What nurses do, I can do

Empowering others

ft has also been wonderful to be able to give other mothers support

Challenging and advocating

I told the doctors if you tried something and it didnt help then Ill accept

it, but dont tell me before the time what you wont do. He is not walking

or talking so let him go. They mustnt have that attitude, they must fight

for him and whatever handicapped child till the end

Facilitating

caregiving

and

home-based

Facilitating ability to cope

within the public health care

sector

The importance of being heard

and offered hope

Essence 7

The continuing

journey:

negotiating

balance

A philosophical, emotional

and spiritual journey

If had been with her all day, in that sorrow, I dont think that I would have

been able toit has been easier for me to grow the hope because we are

walking this thing together, that is enormously comforting

I was very fortunate that my doctor spent a lot of time explaining things to

me

I go and talk to them, thats the way I feel better

Ive also got a challenge in outlook, at how I look where materialism

becomes so apparent

face an ambiguous (unclear and indefinite) loss as their

feelings of loss may not receive public recognition nor be

ritualized as would occur following the death of a child

[38]

Everything changes: Living Life on the Margins

Everything changes: living life on the margins captured

the essence of how the mothers experienced feelings of

isolation. Being the mother of a child with a chronic

feeding difficulty resulted in changes within a broad range

of contexts and had implications for social participation,

employment status, and future plans for these mothers.

Table 2 Reconstruction: getting through the brokenness

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

Activities engage in with ease prior to the diagnosis of a

chronic feeding difficulty became difficult due to the timeconsuming nature of caregiving tasks. The demands of

feeding-related tasks and the need to plan their lives

around mealtimes required the greatest change to the

mothers lives, more so than addressing the physical

difficulties with which their children presented.

The stories show a loss of ability to participate in family

gatherings, social interactions, and full-time employment:

I am just at home, I cant go anywhere, there is nobody

who can give his feeding, it is the feeding that keeps you

away from many things. Relationships with spouses,

extended family members, and friends were altered and

took on new meanings. Marital relationship were either

strengthened or negatively impacted, which appeared to be

related to the degree of paternal participation in caregiving

task as well as the extent to which the mothers

responsibilities as caregiver were acknowledged and

appreciated by the spouse. Restrictions in participation

occurred because of the demanding nature of the childs

caregiving needs; a lack of support in providing the care:

for two years it was just me doing everything his

father cant watch when the PEG has to come out; and a

lack of understanding on the part of friends and family

about the implications of integrating the roles of mother

with caregiver. The experience of loss that was so strongly

felt in relation to their ideals of motherhood extended

further to a loss of social participation and to employment

options.

Disempowered: From Mother to Onlooker

Two broad contexts emerged within which the mothers felt

disempowered, namely, in skill acquisition for adapted

feeding strategies and in emotional capacity to meet the

demands of providing home-based care. The mothers faced

the reality of being expected to cope versus being enabled

to do so. They experienced pressure from family members

and healthcare professionals to cope with the practical and

emotional implications of a chronic feeding difficulty.

When children failed to thrive, regardless of the mode of

nutrition, the mothers reported feeling distressed as they

perceived family members and healthcare professionals to

be judging their feeding practices: when Kevin (not

actual name) was losing so much weight, people will look

at me, or family will look at me and say what is going on,

are you wanting your child to die Maternal feelings of

feeding skills being judged by others was also reported by

Spalding and McKeever [14] and by Thorne et al. [3].

Capacity to cope and role confidence were further

deconstructed when accessing public healthcare services.

The mother experiences a sense of disempowerment in the

healthcare system in which they became passive observers

in the care of their respective children. Their initial

struggle to develop confidence in performing feedingrelated tasks was attributed to the limited time afforded to

them by healthcare professionals during demonstration of

these skills: They expect us to do things for which we are

not trained We have to learn how to do it in a split

second and try to remember it. The manner in which such

skills were demonstrated was characterized as brusque and

rushed thereby discouraging the mothers from raising

questions or discussing their emotional reactions to the

new skills to be performed. Other aspects of professional

interactions that reduced the mothers capacity to cope

included professionals insensitivity to the manner and

place in which information was shared (The doctor told

me to let nature take its course in the ward, in front of

everybody [translated from Afrikaans]); when no hope of

improvement was provided (So while you are sitting there

and hoping for a recovery for your child, they tell you

something and they want you just to give up); when

inaccurate assumptions about the mothers needs were

made (She [the doctor] told me why dont you put him

in a home She said it will be better for me so I said

why must I do it, I can look after him); when they failed

to demonstrate a true interest in the child or the mother;

and excluded mothers from discussion, decision making

and discharge planning ( and they [doctors] dont make

mothers part of discussions, they just say because they are

the doctors).

Mothers in the current study reported that their

information needs were often not met by healthcare

professionals: What would they have told me had I not

asked, and why must I ask, you are the doctor, you are the

therapist. It was difficult for them to make sense of the

diagnosis of dysphagia because they reported a lack of

understanding of the swallowing mechanism, of their

childrens swallowing difficulty, of the measures used to

evaluate swallowing, and especially the rationale for

adapted feeding. Even when a gastrostomy tube was

placed, some mothers lacked the information to understand

the rationale for enteral feeding or the mechanics of

gastrostomy tubes: What is the reason for the PEG? They

have not explained it to me yet. They only told me that a

PEG was going to be inserted. The mothers also

acknowledged that by not making their needs known, by

presenting a faade of being in control both during a

childs hospitalization and in interactions with friends and

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

family members they played a part in limiting their access

to information and of obtaining support: We (mothers)

look happy at the hospital. You sit and smile the whole day

Reconstruction: Getting Through the Brokenness

During the data analysis it became apparent that there was

more to the experience of being the mother of a child with

a chronic feeding difficulty than the deconstructive

processes outlined above. The mothers also spoke of joys

and opportunities for growth that occurred in the presence

of a situation which they described as traumatic, harsh,

and overwhelmingly sad. Getting through the

brokenness was a term used by one mother to describe the

brokenness was a term used by one mother to describe the

process of redefining her life and identity, a process which

was ongoing. Reconstruction occurred as these mothers

made positive personal adaptations through a process of

redefining the mother identity, celebrating the

positives, becoming the enabler, and engaging in an

ongoing journey of philosophical, emotional and spiritual

change

Letting go of the Dream and Valuing the Real

A redefining of mother occurred as these mothers

integrated the roles associated with being a mother with the

specialized care needs that they associated with being a

caregiver or nurse. The initial role conflict between mother

and caregiver that emerged was similarly found in a study

by Judson [39]. She too found a conflict between

mothering versus nursing roles for mothers who were

providing home-based care. What emerged from the

current study was that the mothers appeared to progress to

a stage where the roles of nurturing mother and resolute

caregiver (associated with tasks during which they had to

harden themselves) became integrated, thereby enabling

them to perform the diverse roles just becomes part of the

whole. The ability to incorporate the caregiver identity

into their identity as mother illustrated one aspect of

positive personal growth.

A recurring theme in the literature on home-based

care provided to children with disabilities and chronic

medical needs is the presence of caregiver feelings of

being overburdened [40, 41]. However, the mothers in the

there at the hospital but when you go home you cry you

have to appear strong in front of them.

current study demonstrated an ability to recognize both

positive and negative outcomes. Blaska [17] also found

that the presence of grief does not necessarily prevent

parents from identifying positive consequences of having a

child with a disability. For the mothers in this study it

appeared that they were able to identify and celebrate

positive changes in they were able to identify and celebrate

positive changes in their children once they modified their

ideals of a child and expectation of childhood development

"I think there are more moments now for me that I see her

as the most incredible gift, and I think the important thing

is let the gift be who, what it is instead of what you want it

to be." The ability to redefine their beliefs about being a

mother and to celebrate positive changes, in the presence

of ongoing feeling of loss and sadness, was a universal

theme that emerged from all the interviews irrespective of

the length of time that the child had been living with the

length of time that the child had been living with the

feeding difficulty, which ranged from 6 months to

approximately 13 years. The mothers were all able to "get

through the brokenness" of their situation and find

encouragement in change and progress: "She is who she

is... there is nothing to be, nothing lost. Everything we get

every day is a gain, it is something extra. And she can

cough, and she can laugh and she can smile." Personal

growth in times of stress and trauma or "post-traumatic

growth" has been documented [42, 43] and reflect the

findings of the current study as the mothers demonstrated

growth arising out of a situation that they experience as

traumatic. Their ability to increase their competence and

capacity to cope may have been influenced by their ability

to redefine themselves as mothers as well as celebrating

their children's achievements that were not necessarily

aligned to the attainment of development milestones.

Self-Empowered: Becoming the Enabler

Baksi and Cradock [44] define empowerment as a process

whereby knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-awareness

are gained. The term self-empowered was chosen to define

this essence because for the mothers, the enabler or the

agent that endowed them with power was themselves.

When recalling early disempowering interactions with

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

healthcare professionals it emerged that the mothers did

not feel that they could request assistance or confront

professionals: "I am alone with this doctor. Why don't I say

something! "In contrast to such feeling of powerlessness

was a change that occurred in the mothers toward

becoming empowered which was linked to gathering

information and acquiring skills.

It has been found that parents experience less stress

during a child's hospitalization when they gain control over

the situation through the gathering of information about

their child's medical difficulties and treatment options [2,

45]. These findings are relevant to the current study

because the mothers also demonstrated an increased

perception of control of their situation through gathering of

information. Information was sought from healthcare

professionals ("So tell me what I want to know"), but when

parents were not able to able to obtain the information they

needed from professional, they actively found alternative

sources of information such as other parents, support

groups, and the internet.

Personal growth occurred for the mothers in this study as

they spoke of an increased ability to challenge healthcare

professionals ("One needs to be able to say: No, I don't

agree with it") and as they began to question public

healthcare policies. The current study therefore supports

findings that mothers may initially adopt a passive role in

relation to the medical management of their respective

children but that this passivity is replaced by and assertive

attitude in which they demand to be acknowledged and for

medical management to be in line with their wishes

because of acquired information [46, 47].

The mothers spoke of growth that occurred over time

in terms of their ability to perform various care tasks

associated with adapted feeding strategies. One mother

was greatly assisted by a healthcare professional who took

the time to ensure that skills were mastered. However, the

reality for the other mother was that "...there was not

anybody specifically guiding you." Competence was

gained through their own trial-and-error attempts: "We

give him something (to eat), and then we see how it works"

(translated from Afrikaans). As was found in a study aimed

at examining the process of mothering a child who was

reliant on parenteral nutrition [39], the mother in this

study also experience a powerful need to find structure in

gaining some measure of control over the challenges of

caring for their children.

Positive personal growth was further evidenced in their

empowerment of family members and even strangers. The

mothers shared their acquired skills ("...I trained Betty [not

actual name] to finger feed") and knowledge with family

members ("I downloaded information from the internet.

We printed everybody a booklet about cerebral palsy,

feeding issues...") They furthermore expressed a wish to be

able to empower other mothers by providing information,

practical skill demonstration, and emotional support ("I

would love to be there in the doctor's rooms when an initial

diagnosis is made, to say to the mother that she is not

alone, and that there are other mothers that can walk the

road with her"), a wish that has not been previously

identified in other similar studies [5, 9, 10].

An additional role identity emerged in most of the

mother as they felt a need to advocate for the rights of

children with disabilities. The mothers in this study

identified the need to promote equal treatment options for

children with disabilities in the public healthcare system.

Advocating for the rights of children with special needs

and challenging healthcare services and policies were also

found in McKeever's study [47] as the mothers moved

from a compliant to an assertive role through knowledge

and skill acquisition. Similar to Douglas and Michael's

finding [48], some of the mothers in this study were also

very aware of the images portrayed in popular media of

motherhood and how they were not able to relate to such

images. They expressed a desire to advocate for increased

representation of children with feeding difficulties in

popular media: "There is a TV programme all about

feeding... but there is not a single thing about feeding a

especial needs child. I think that I should write to them..."

"Self-Empowered: Becoming the Enabler"

Illustrated positive personal growth that occurred in the

mothers in areas such as acquiring information, support,

skills, and confidence.

The mothers empowered

themselves out of necessity because they were required to

perform specialized care tasks as the primary

caregivers, often without support from others, through

trial-and-error attempts. This empowerment was achieved

by taking control of the situation demonstrated in the

establishment of daily schedules, by finding and/or

creating sources of support, and through a discovery of

their own inner reserves. Their stories illustrated growth

that occurred from initially being passive observers in their

children's care to becoming empowered women as they

took control of their lives. The growth that occurred did

not, however, replace feeling of loss. Even though the

mothers moved toward a position of strength over time,

they also recounted instances where they returned to

feeling of disempowerment and sorrow: "...often what one

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

loses is the magic in the harshness, and I think that is what

I am trying to see again... but I can still feel beaten down."

Facilitating the Journey.

The experiences of the mothers in this study, depicted as an

ongoing journey, must be understood within the contexts of

providing home-based care and accessing public healthcare

services. The mothers identified a number of factors that

enabled their capacity to cope or helped them through their

journey of providing care for their children. Sources of

support within the two contexts of home-based caregiving

and the public healthcare setting ranged from spouses,

extended family members, coworkers, support groups, and

healthcare professionals.

The mothers demonstrated interpersonal coping

behaviors

they

accepted

support

offered

by

spouses, extended family members, and coworkers: "...we

(she and her husband) take turns and help each other with

everything that needs to be done..." Where such support

was not present, one mother was proactive in creating a

support group that could meet her practical and emotional

needs: "The nice thing about my support group is that we

phone each other, ..., we give each other support." The

availability of respite care or the sharing of daily

caregiving tasks was highly valued by the mothers;

however, it often was not offered by either extended family

members or home-based care agencies: "I told her (homebased carer) that I would teach her how to do it (enteral

feeding). But then she never came black. She said that she

is sorry but she would not be able to do it, she can't work

on a child with a PEG" (translated from Afrikaans).

Emotional support was gained when the mothers felt that

family members and friends understood their child's

caregiving needs, the concerns they had for the child's

future, and the emotional impact of having to fulfill the

role of primary home-based caregivers.

Supportive professional interactions played a role in

facilitating the mothers ability to cope with the challenges

of a feeding difficulty as well as creating a positive

perception of the public healthcare setting. The mothers

valued interactions with professional where the latter

showed an interest in the child, acknowledged the

mother's effort, displayed kindness, developed a

relationship with the mother, imparted skills, provided

options, and allowed the mother to make decisions. The

key factor that emerged from the current study was that

professional interactions were valued when a partnership

rather than a paternalistic professional-patient relationship

was established: "...I am very fortunate with my

pediatrician. She recommended that we go onto PEG

feeding. Initially I was resistant to the idea but agreed to

nasogastric feeding ... we started off with NG feeding...

and then it became just too much... so I went back to my

doctor and at that stage she arranged that I could see a little

baby that had a PEG in place." These findings are in line

with research on parent-professional communication in

pediatric healthcare setting by Nobile and Drotar [49].

They too found that parental satisfaction with care was

most frequently associated with effective parentprofessional communication in which the professional

showed genuine interest in the family and affirmed the

parents' effort and active participation. Interacting with

other mothers in similar situations during a child's

hosptalisation also emerged as an enabling factor when

accessing public healthcare services: "She (another

mother) was like a social worker... we shared everything.

The first week at home was difficult because I missed her

and wondered who am I going to talk to now. "Parent-toparent support has been shown to be a valuable tool in

enabling capacity to cope [50], which in the current study

did not appear to be encouraged or facilitated in different

hospital

accessed

by

the

mothers.

Apart from the agencies and individuals who were offering

support, two attributes emerged that were highly valued by

the mothers, namely "Hearing" is used in this context to

signify a true understanding of the person rather than

merely affording them time through listening.

Experiencing a sense of being "heard" or understood has

been identified as a powerful positive influence on people's

ability to make meaning of their lives [51]. For the mothers

who took part in this study, the perception of truly being

heard was seen as an enabler of capacity to cope: "I think it

would be amazing for them (doctors) to... actually sit and

read through what the experiences are like..." The second

attribute, being offered hope, was closely linked to a need

to see a way forward, or a plan for the future: "Just give

them (mothers) that hope and they will push forward." A

discourse of hope also emerged from a study by Thorne et

al. [3]. They found that healthcare professionals often

failed to understand the significance of recommending

gastrostomy placement to parents in their study, which

also was found in the current study, was that it signified an

end in the current study, was that it signified an end in the

hope of recovery for a child ("... initially I was very

resistant to the idea because it sort of felt like that was the

end, you know, only very sick people or people close it

death goes onto tube feeding"), which may be perceived by

healthcare professionals as irrational refusals of enteral

feeding.

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

The Continuing Journey: Negotiating Balance.

The mothers were engaged in an ongoing process of

negotiating personal meaning as they "got used to" and

"adapted to" their changed lives but did not necessarily

reach complete acceptance. The current study supports

findings of Calhoun et al. [43] by also identifying growth

that occurred within three domains, i.e., changes in

perception of self, changed relationships with others, and a

changed world view that included a deeper appreciation for

life and setting of new priorities. Their experiences

became a philosophical, spiritual, and emotional journey as

they developed an increased degree of introspection, ability

to examine, question, and redefine their beliefs: "Because

it is very easy to believe and trust when everything is fine,

but when it is not! I just think that, that is how your

character is built... but definitely my faith is much

stronger." Focusing on the present and accepting undertainty and change as a means to reach personal growth

emerged from the stories: "...if we embrace the changes, I

think we grow, otherwise we do get stuck." While Judson

[39] found that the mothers in her study refused to dwell

on the past, in the current study the mothers reached a

point where they could balance acknowledged losses with

a future-focused outlook. Being the mother of a child with

chronic feeding difficulties therefore afforded apportunities

for increased introspection which resulted in practical,

emotional, spiritual, and philosophical growth. The current

study supports the premises of post-traumatic growth

theories: that experiences of loss can act as a catalyst for

personal growth [42].

Conclusion: The Ebb and Flow of Deconstruction and

Reconstruction.

Professional journals and popular media are filled with

apparently contradictory statement focusing on either the

positive [52, 53] or negative [40, 41] implications of

parenting a child with special needs. What emerged from

the stories of the mothers in this study was that the positive

and negative experiences were not mutually exclusive but

often co-occurred. They spoke of increased demands and

stress associated with caring for a child with chronic

feeding difficulties while at the same time giving voice to

their increased personal resilience and ability to cope. The

journey continues as the mothers move between

contradictory feeling of acceptance and denial in an

ongoing negotiation of balance-seeking in term of both

emotions (strength and insecurity) and opposing roles

(mother and caregiver). The process appeared to be

cyclical in the sense that it was not a direct path toward

reconstruction without, at times, returning to the feeling

associated with deconstruction. This ongoing journey

stands in contrast to theories emphasising the need to reach

an ideal of complete acceptance of loss as is described in

stage theories of grief [54]. The presence of both strength

and perception of "brokenness" and how these mothers

managed to deal with such opposing experiences can be

understood in relation to a continual balancing of loss with

a focus on positive outcomes. What in fact emerged was

that the mothers' experiences and adjustments to a state of

unbalance were the driving forces that often resulted

I positive personal growth. The phenomenon of being the

mother of a child with a chronic feeding difficulty

continues to be a transformative experience in which posttraumatic growth co-occurs with chronic sorrow.

Implications and Recommendations.

It is hoped that this study will stimulate and guide

engagement with mothers who are providing home-based

care. While the study has been delineated within the

context of public healthcare, it is believed that the findings

will add value to all healthcare, professional and

organizations involved in the care of children with chronic

feeding and/or swallowing difficulties. To support families

one needs to be aware of how mothers experience their role

as

the

primary

caregiver.

Empowerment of mothers will require a combination of

approaches to meet both practical and should actively gain

insight into a mother's experiences by creating an

environment in which Require both " humanity and

expertise" [55] from healthcare professionals should

involve truly "hearing" the mother and not discouraging

the hope that she has for her child, despite having to offer

truthful information about a child's prognosis. Those

involved in the care of children with chronic feeding

difficulties can potentially facilitate the process through

which a mother redefines herself and how she construct

meaning regarding her child. A shift in focus from the

disability and medical complications toward identifying

abilities in the child could be fostered. To support mothers,

healthcare professionals need to be aware of the pervasive

and persistent feeling of loss experienced due to an

inability to feed a child orally or with ease. This awareness

of the emotional reaction to enteral nutrition is crucial

when informing mothers of feeding strategy to be

implemented. Furthermore, practical needs in relation to

adapted feeding strategies should be met by allowing for

R. Hewetson, S. Singh: Mothers of Children with Feeding/Swallowing Difficulties

sufficient time to demonstrate and facilitate acquisition of

skills, verification of understanding is crucial, and followup assistance (e.g., referral to respite care, support groups,

relevant literature) must be provided. Unanswered

questions about dysphagia has serious implications as it

reduces the mothers' ability be spent in describing the

nature of swallowing difficulties and ideally should be

accompanied by written and pictured/video information

and encouragement of questions. Parents should be

involved in evaluations of swallow safety so that specific

recommendations may be accepted and optimize carryover

to the home environment. Mothers appear to have the

capacity and desire to play a role in educating and

supporting other mothers who are providing home - based

care for children with chronic feeding difficulties. An

awareness of the role that they could play in this regard

may act as a catalyst for the establishment of parent-to-

parent

support

groups.

The intention of this study was not it provide the final

word on the phenomenon, but hopefully to increase

awareness of the need for further research aimed at

improving service delivery. Little is known about the

impact of providing home-based care on the mother's

construction of meaning for her changed role and life. It is

hoped that the analysis of the structure and processes of the

mother's experiences will add to the development of theory

concerning this experience and in defining effective

practice.

Вам также может понравиться

- When Your Child Won’T Eat or Eats Too Much: A Parents’ Guide for the Prevention and Treatment of Feeding Problems in Young ChildrenОт EverandWhen Your Child Won’T Eat or Eats Too Much: A Parents’ Guide for the Prevention and Treatment of Feeding Problems in Young ChildrenОценок пока нет

- Breastfeeding Duration and Early Parenting Behaviour The Importance of An Infant-Led, Responsive StyleДокумент7 страницBreastfeeding Duration and Early Parenting Behaviour The Importance of An Infant-Led, Responsive Styleadri90Оценок пока нет

- Early Breastfeeding Experiences of Adolescent Mothers: A Qualitative Prospective StudyДокумент14 страницEarly Breastfeeding Experiences of Adolescent Mothers: A Qualitative Prospective StudyRetno MandriyariniОценок пока нет

- Title: Exploring The Various Infant Feeding Practice Among Mothers Attending Infant Welfare Clinic at Holy Trinity Ekona. Name: Neh Doreen No:1244Документ5 страницTitle: Exploring The Various Infant Feeding Practice Among Mothers Attending Infant Welfare Clinic at Holy Trinity Ekona. Name: Neh Doreen No:1244Lucien YemahОценок пока нет

- Article 1Документ10 страницArticle 1nishaniindunilpeduruhewaОценок пока нет

- Changes in Feeding Among Children With Cerebral PalsyДокумент13 страницChanges in Feeding Among Children With Cerebral PalsyadriricaldeОценок пока нет

- Research Article: An Assessment of The Breastfeeding Practices and Infant Feeding Pattern Among Mothers in MauritiusДокумент9 страницResearch Article: An Assessment of The Breastfeeding Practices and Infant Feeding Pattern Among Mothers in MauritiusNurhikmah RnОценок пока нет

- 13 Ashwinee EtalДокумент5 страниц13 Ashwinee EtaleditorijmrhsОценок пока нет

- Training Nurses To Save Lives of Malnourished Children: Research ArticleДокумент7 страницTraining Nurses To Save Lives of Malnourished Children: Research ArticlefirdakusumaputriОценок пока нет

- Nutrition Related Knowledge and Attitudes of Mothers and Teachers of Kindergarten ChildrenДокумент8 страницNutrition Related Knowledge and Attitudes of Mothers and Teachers of Kindergarten ChildrenIJPHSОценок пока нет

- Peer Education Is A Feasible Method of Disseminating Information Related To Child Nutrition and Feeding Between New MothersДокумент8 страницPeer Education Is A Feasible Method of Disseminating Information Related To Child Nutrition and Feeding Between New MothersKomala SariОценок пока нет

- Fat Kids Are Adorable The Experiences of Mothers Caring For Overweight Children in IndonesiaДокумент9 страницFat Kids Are Adorable The Experiences of Mothers Caring For Overweight Children in IndonesiaLina Mahayaty SembiringОценок пока нет

- Nutrients 15 00988Документ17 страницNutrients 15 00988VIRGINA PUTRIОценок пока нет

- Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Hanne Kronborg, Ingegerd Harder, Elisabeth O.C. HallДокумент6 страницSexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Hanne Kronborg, Ingegerd Harder, Elisabeth O.C. HallAridayana HalideОценок пока нет

- 1018-Article Text-4791-1-10-20210707Документ10 страниц1018-Article Text-4791-1-10-20210707Lavi LugayaoОценок пока нет

- AssociationofmaternalnutritionknowledgeandchildДокумент7 страницAssociationofmaternalnutritionknowledgeandchildKomala SariОценок пока нет

- Systematic Review of Interventions Used in or Relevant To Occupational Therapy For Children With Feeding Difficulties Ages Birth-5 YearsДокумент8 страницSystematic Review of Interventions Used in or Relevant To Occupational Therapy For Children With Feeding Difficulties Ages Birth-5 YearsGabriela LalaОценок пока нет

- Breast-Feeding Performance Index - A Composite Index To Describe Overall Breast-Feeding Performance Among Infants Under 6 Months of AgeДокумент9 страницBreast-Feeding Performance Index - A Composite Index To Describe Overall Breast-Feeding Performance Among Infants Under 6 Months of AgeHuan VuongОценок пока нет

- Korn Ides 2013Документ10 страницKorn Ides 2013Nanda AlvionitaОценок пока нет

- Complementary Feeding: A Practice Between Two Knowledges: La Alimentación Complementaria: Una Práctica Entre Dos SaberesДокумент9 страницComplementary Feeding: A Practice Between Two Knowledges: La Alimentación Complementaria: Una Práctica Entre Dos SaberesMaria EugeniaОценок пока нет

- Johnson2015 Article BehavioralParentTrainingToAddrДокумент17 страницJohnson2015 Article BehavioralParentTrainingToAddrQuel PaivaОценок пока нет

- Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Baby-Led-Weaning by Health Professionals and Parents A Cross-Sectional Study.Документ7 страницKnowledge and Attitudes Towards Baby-Led-Weaning by Health Professionals and Parents A Cross-Sectional Study.myjesa07Оценок пока нет

- Attitudes Toward Breastfeeding and Breastfeeding Practice: Lack of Support For Breastfeeding in Public As A Factor in Low Breastfeeding RatesДокумент7 страницAttitudes Toward Breastfeeding and Breastfeeding Practice: Lack of Support For Breastfeeding in Public As A Factor in Low Breastfeeding RatesOmer JakupovicОценок пока нет

- BMC Public Health Journal 2014.originalДокумент9 страницBMC Public Health Journal 2014.originalfruitfuckОценок пока нет

- Food Taboos and Myths in South Eastern Nigeria: The Belief and Practice of Mothers in The RegionДокумент6 страницFood Taboos and Myths in South Eastern Nigeria: The Belief and Practice of Mothers in The RegionBrilianita TrisnaОценок пока нет

- Rume Chapter Five PDFДокумент7 страницRume Chapter Five PDFHarrison RumeОценок пока нет

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis of The Parental Feeding Style Questionnaire With A Preschool SampleДокумент8 страницConfirmatory Factor Analysis of The Parental Feeding Style Questionnaire With A Preschool SampleCaterin Romero HernándezОценок пока нет

- Issaka Et Al-2015-Maternal & Child Nutrition PDFДокумент17 страницIssaka Et Al-2015-Maternal & Child Nutrition PDFikaОценок пока нет

- Breakfast Skipping Among Medical StudentsДокумент12 страницBreakfast Skipping Among Medical StudentsJoy DiasenОценок пока нет

- BMC Public HealthДокумент10 страницBMC Public HealthPam Travezani MiyazakiОценок пока нет

- Sdarticle 142 PDFДокумент1 страницаSdarticle 142 PDFRio Michelle CorralesОценок пока нет

- The Finger Feeding MethodДокумент7 страницThe Finger Feeding MethodInés Valero ArredondoОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1Документ6 страницChapter 1Geralden Vinluan PingolОценок пока нет

- 2007 FoodNutrBull 375 RoySKДокумент9 страниц2007 FoodNutrBull 375 RoySKhafsatsaniibrahimmlfОценок пока нет

- Jurnal 2Документ5 страницJurnal 2desianabsОценок пока нет

- Literature Review On Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Exclusive BreastfeedingДокумент7 страницLiterature Review On Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Exclusive Breastfeedingfvg6kcwyОценок пока нет

- General Practitioners Knowledge of Breastfeeding Management: A Review of The LiteratureДокумент8 страницGeneral Practitioners Knowledge of Breastfeeding Management: A Review of The LiteratureshairaОценок пока нет

- A Responsive Feeding Intervention Increases ChildrДокумент7 страницA Responsive Feeding Intervention Increases Childrandayu nareswariОценок пока нет

- In Uences On Infant Feeding Decisions of First-Time Mothers in Five European CountriesДокумент6 страницIn Uences On Infant Feeding Decisions of First-Time Mothers in Five European CountriesPoppyОценок пока нет

- Example Literature Review On Childhood ObesityДокумент6 страницExample Literature Review On Childhood Obesityc5praq5p100% (1)

- N331 Obstetric Clinical Case Study Purpose of The AssignmentДокумент3 страницыN331 Obstetric Clinical Case Study Purpose of The Assignmentapi-281915802Оценок пока нет

- Managing Encopresis in The Pediatric Setting: The DSM-5 Autism Criteria: A Social Rather - .Документ5 страницManaging Encopresis in The Pediatric Setting: The DSM-5 Autism Criteria: A Social Rather - .Yurizna Almira Nst IIОценок пока нет

- Perceptions and Practices Regarding Breastfeeding Among Postnatal Women at A District Tertiary Referral Government Hospital in Southern IndiaДокумент7 страницPerceptions and Practices Regarding Breastfeeding Among Postnatal Women at A District Tertiary Referral Government Hospital in Southern IndiaJamby VivasОценок пока нет

- A Study To Determine The Effectiveness of An Awareness Programme On Knowledge and Attitude About Low Weight Child Between 5-10 Yrs Among Nurses StudentДокумент40 страницA Study To Determine The Effectiveness of An Awareness Programme On Knowledge and Attitude About Low Weight Child Between 5-10 Yrs Among Nurses StudentSanket TelangОценок пока нет

- Ed621794 PDFДокумент10 страницEd621794 PDFAbello Cristy JaneОценок пока нет

- Practical Research 1 Effec of Early Pregnancy On Educational Attainment of YouthДокумент13 страницPractical Research 1 Effec of Early Pregnancy On Educational Attainment of Youthlime TantraОценок пока нет

- Gizkes LanjutДокумент8 страницGizkes LanjutSaeful AnhariОценок пока нет

- Baby-Led Weaning The Evidence To DateДокумент9 страницBaby-Led Weaning The Evidence To DateCristopher San MartínОценок пока нет

- Literature Review On Knowledge and Practice of Exclusive BreastfeedingДокумент5 страницLiterature Review On Knowledge and Practice of Exclusive Breastfeedingc5rh6ras100% (1)

- Pacifier and Bottle Nipples: The Targets For Poor Breastfeeding OutcomesДокумент3 страницыPacifier and Bottle Nipples: The Targets For Poor Breastfeeding Outcomesbeleg100% (1)

- Application of HBMДокумент15 страницApplication of HBMSashwat TanayОценок пока нет

- Amamentacao Habitosalimentares 2020Документ10 страницAmamentacao Habitosalimentares 2020crisitane TadaОценок пока нет

- Annotated BibliographyДокумент6 страницAnnotated BibliographyNidhi SharmaОценок пока нет

- A Major ResearchProposal Group9 BSN3D v1.0 20210117Документ17 страницA Major ResearchProposal Group9 BSN3D v1.0 20210117Iosif CadeОценок пока нет

- International Breastfeeding JournalДокумент9 страницInternational Breastfeeding JournalNanda AlvionitaОценок пока нет

- The Effectiveness of Community-Based Nutrition Education On The Nutrition Status of Under-Five Children in Developing Countries. A Systematic ReviewДокумент4 страницыThe Effectiveness of Community-Based Nutrition Education On The Nutrition Status of Under-Five Children in Developing Countries. A Systematic ReviewDesy rianitaОценок пока нет

- Baby Led Weaning Vs Parent LedДокумент12 страницBaby Led Weaning Vs Parent LedAdil SultaniОценок пока нет

- Literature Review On Knowledge of Exclusive BreastfeedingДокумент7 страницLiterature Review On Knowledge of Exclusive BreastfeedingaflruomdeОценок пока нет

- Nutrients 13 02376Документ28 страницNutrients 13 02376Garuba Olayinka DhikrullahiОценок пока нет

- Lembar Balik3Документ8 страницLembar Balik3Vhita GandolОценок пока нет

- 2nd Tongues WorkshopДокумент9 страниц2nd Tongues WorkshopGary GumpalОценок пока нет

- Heli Electric Stacker Cdd14 930 Parts Manual ZH enДокумент23 страницыHeli Electric Stacker Cdd14 930 Parts Manual ZH enhadykyx100% (42)

- What Are The Advantages and Disadvantages of UsingДокумент4 страницыWhat Are The Advantages and Disadvantages of UsingJofet Mendiola88% (8)

- Shamanism and ShintoДокумент2 страницыShamanism and ShintojmullinderОценок пока нет

- Saint Raphael, The ArchangelДокумент10 страницSaint Raphael, The Archangelthepillquill100% (1)

- Senarai Nama Buddy TerkiniДокумент14 страницSenarai Nama Buddy TerkiniYap Yu SiangОценок пока нет

- Trans Tipping PointДокумент10 страницTrans Tipping Pointcelinebercy100% (3)

- Six Paramitas - Tai Situ RinpocheДокумент16 страницSix Paramitas - Tai Situ Rinpochephoenix1220Оценок пока нет

- AUL Icoeur and Religion: AUL Icouer E A ReligiãoДокумент10 страницAUL Icoeur and Religion: AUL Icouer E A ReligiãoJohn ManciaОценок пока нет

- Migne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 63.Документ738 страницMigne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 63.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisОценок пока нет

- 7 Garces V Estenzo - DIGESTДокумент1 страница7 Garces V Estenzo - DIGESTMarga Lera100% (1)

- Gardela L. 2015 Vampire Burials in Medie PDFДокумент22 страницыGardela L. 2015 Vampire Burials in Medie PDFvalacugaОценок пока нет

- Finding Refuge by Harold Sala - Chapter 1Документ15 страницFinding Refuge by Harold Sala - Chapter 1Omf Literature100% (5)

- Sadhana Chants: Long Ek Ong Kar - "Morning Call" (7 Minutes)Документ2 страницыSadhana Chants: Long Ek Ong Kar - "Morning Call" (7 Minutes)raminderjeetОценок пока нет

- ExistencialismДокумент1 страницаExistencialismolivia1155Оценок пока нет

- Nil Santiáñez. Topographies of FascismДокумент5 страницNil Santiáñez. Topographies of Fascismgbaeza9631Оценок пока нет

- Reflection English + MyanmarДокумент258 страницReflection English + Myanmaradoniram junior100% (2)

- Prácticas Funerarias JudáicasДокумент321 страницаPrácticas Funerarias JudáicasNataly MendigañaОценок пока нет

- Hilchos Niddah Condensed Ss 2-1-12Документ2 страницыHilchos Niddah Condensed Ss 2-1-12Daville BulmerОценок пока нет

- OPPT Definitions PDFДокумент2 страницыOPPT Definitions PDFAimee HallОценок пока нет

- Living PromisesДокумент6 страницLiving PromisesMark MerhanОценок пока нет

- Shree Hanuman ChalisaДокумент2 страницыShree Hanuman ChalisaamitbanneОценок пока нет

- AJAPA Japa MeditationДокумент15 страницAJAPA Japa Meditationvin DVCОценок пока нет

- D20 - 3.5 - Spelljammer - Shadow of The Spider MoonДокумент49 страницD20 - 3.5 - Spelljammer - Shadow of The Spider MoonWilliam Hughes100% (3)

- Indian Culture and HeritageДокумент1 329 страницIndian Culture and HeritageNagarjuna DevarapuОценок пока нет

- Updated 3rd Batch Provisional Admissions 2022 2023 OriginalДокумент228 страницUpdated 3rd Batch Provisional Admissions 2022 2023 OriginalThe injaОценок пока нет

- Highlands - LCCДокумент2 страницыHighlands - LCCHerbert Anglo QuilonОценок пока нет

- ISB 542 Introduction To Fiqh Muamalat: The Concept of Property (Al-Maal) in IslamДокумент22 страницыISB 542 Introduction To Fiqh Muamalat: The Concept of Property (Al-Maal) in IslamsophiaОценок пока нет

- 1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 4 Powerpoint With Tagalog NotesДокумент25 страниц1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 4 Powerpoint With Tagalog NotesRitchie FamarinОценок пока нет

- Basic Facts About Yiddish 2014Документ26 страницBasic Facts About Yiddish 2014Anonymous 0nswO1TzОценок пока нет