Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Hasmonean Coins Found in The Cave of The Warrior

Загружено:

Beagle75Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Hasmonean Coins Found in The Cave of The Warrior

Загружено:

Beagle75Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Appendix

HASMONEAN COINS FOUND IN THE CA VE OF THE WARRIOR

Donald T. Ariel

The coins found in the Cave of the Warrior, while they

do not relate to the important early fourth millennium

finds in the cave, throw light on some interesting historical events that took place between the years 40 and 37

BCE.' In general, the Judean Desert and in particular

Jericho are reported by the historian Josephus as playing

a prominent role in the events of those years. The coins

from the Cave of the Warrior, together with the distribution of similar coins found in the region, contribute to

our understanding of the region's historical prominence.

THE COINS

The nine coins found in the cave are all of the reign of

one king, the Hasmonean Antigonus (Hebrew: ~'nnr.>

Mattathias), who ruled 40-37 BCE. All of Antigonus'

coins were minted in Jerusalem. Unlike other contemporary series of coins minted in the region, Antigonus

minted bronze coins in three denominations following

the Seleucid denominational system (Kindler 1967: 187188). He struck a (small) perutalz denomination, and

thus maintained continuity with the perutah (l.5-2.0

gm) denominations minted by his Hasmonean predecessors. In one case (AJC 1:158, Type W) Antigonus followed the classic Hasmonean type: inscription-withinwreath/double cornucopias, with the priestly sceptre between them (generally identified as a pomegranate):The

two larger denominations were four (AJC I: 158, Type

V) and eight (AJC I: 158, Type U) times the perutalz.

Similarly large denominations were also minted by Antigonus' rival Herod during the same period. It has been

suggested (Kanae! 1967:227) that the larger denominations were minted by Antigonus and Herod in order to

supply the Roman troops with large coins such as they

were accustomed to (but compare Meshorer 1990:223).

It can indeed be contended that soldiers were paid not in

bronze but rather in silver. This is true for the stipendium

(soldier's pay). For use as small change in daily transactions, the legionaries' preference would have definitely.

been for large bronze coins.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND'

Between 63 and 40 BCE, Antigonus' uncle, Hyrcanus

II, was high priest, and, for all or part of that time, also

ethnarch, which was largely a titular position. As early

as 56 BCE, Antigonus, with his father Aristobulus II,

had been involved in an earlier unsuccessful military

attempt to wrest control of the region from Roman

rule. In 47 BCE Antigonus appeared before Caesar, and

unsuccessfully presented his claim to rule.

By 42 BCE there were two contenders for control

over Judea: Antigonus and Herod. The latter had been

appointed (with his brother Phasael) tetrarch over the

Jewish territory. Antigonus' installation as king/high

priest by the Parthians in 40 BCE was based upon his

promise to depose both his Roman-appointed uncle and

the tetrarch Herod - as well as a promise to deliver to

the Parthians 1000 talents of silver and 500 women

(Josephus, War i.13.4 (257); Ant. xiv. 13.3 (330-331)).

Antigonus proceeded to Jerusalem, where his supporters

sparred with Herod and Phasael's supporters for control

of the city (Josephus, War i.13.2 (250-252); Ant. xiv.

13.3-4 (334-337)). By early summer 40 BCE Phasael

and Hyrcanus II were tricked into going to the camp

of the Parthian Barzaphranes, where they were taken

captive, while Herod and the rest of his family escaped

Jerusalem towards Masada. On the way, near the future

132

DONALD T. ARIEL

site of Herodion, the forces of Antigonus attacked

Herod (Josephus, War i. 13.8 (265); Ant. xiv. 13.9 (359)).

This confrontation is the first indication of Antigonus'

n1ilitary activity against Herod in the Judean Desert.

Herod's entourage survived the attack and continued

on to Masada, where the family remained, while Herod

continued to Petra and then to Rome to seek support

for his cause. In Rome Herod was appointed (vassal)

king by Marc Anthony, and the appointment was ratified by the Senate. All this time Antigonus' men besieged

Herod's family at Masada (Josephus, War i. 15.1 (286287); Ant. xiv. 14.6 (390-391)). Meanwhile the Parthian

army was defeated by the Roman legions, and Herod

returned to the region to prepare for his campaign

against Antigonus. Herod (with the intermittent aid of

Roman forces under Silo) succeeded in subduing large

parts of the country. Herod then turned to free his family

in Masada, which until then had been under siege by

Antigonus' men (Josephus, War i.15.1 (293-294); Ant.

xiv. 14.6 (398)). Apparently, somewhere in the Judean

Desert, Antigonus tried to stop Herod's advance, but

Herod succeeded in getting to his family in Masada.

Herod proceeded to Jerusalem and mounted a siege,

but as the winter of 39/38 approached, Herod also had

to arrange for provisions for his and Silo's armies. He

prepared a convoy of provisions in Jericho, \vhich, on

its way from there to Jerusalem was ambushed by

Antigonus' forces. Thereupon Herod himself, with a

large contingent of soldiers, descended to Jericho and

found the town almost abandoned (Josephus, TYar i.15.6

(300); Alli. xiv. 15.3 (409)). Silo's forces soon arrived as

\Vell and plundered the

tO\Vll.

Not wanting to cause

further disaffection in the local population Herod

moved the Ro1nans to \Vinter quarters elsewhere.

Around this time Herod fortified the Judean desert

fortress of Alexandrium.

After the final fall of the Parthians in June 38 Herod

\vent to Satnosata, leaving his now augn1ented forces

under the command of his brother Joseph, together with

the Roman forces based in Samaria. Joseph took these

Roman troops to mountains apparently above Jericho

and planned a foray to confiscate the harvest in that

town. Antigonus' troops were also in the area. Along

with the sympathetic population which had returned to

a plundered Jericho, they attacked Joseph 'on difficult

ground in the hills' (Josephus, War i.17.1 (324); Ant.

xiv. 15.10 (449)), won the skirmish and killed Joseph.

On his return, Herod led Ro111an and other troops to

Jericho to avenge his brother's death. The day after his

arrival so111e 6,000 of Antigonus' men attacked the town

from the hills (Josephus, War i.17.4 (332); Am. xiv. 15.2

(456)). In the battle that ensued, Herod was wounded

by a spear in his rib. As we shall see (below), the hills

noted above were in all liklihood the place of the archaeological survey and excavations of Operation Scroll,

where many coins of Antigonus were found.

While we do not know the outcome of the battle,

Herod succeeded in extricating himself: later he went

on to subdue Antigonus' troops, besiege Antigonus in

Jerusalem, conquer the city and capture Antigonus.

Consequently Herod gained full control of his kingdom

in the summer of 37 BCE.

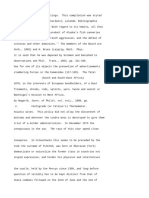

DISTRIBUTION OF ANTIGONUS' COINS (see Fig. Ap.l)

Isolated coins of Antigonus have been found in numerous excavations, and as well as stray finds in the region.

It is not surprising that the majority were found in

Jerusalem, where they were minted. (A mould used for

making the flan employed in his large coins was uncovered in excavations in Jerusalem; see An1iran and Eitan

1975:53-54.) Twenty-two isolated coins of Antigonus

have been published from Jerusalem and environs: 14

in Ariel 1982:322 (one of these is published in Mazar

197l:Pl. XXVIII:3, and another three in Gitler 1996:

348-349, Nos. 238-240); 1 in Ariel 1990:105, C 135; 4

in Lawrenz 1985:160, Nos. 149-152; and 3 from unpublished excavations in Jerusalem (!AA 27968, 3312433125). In addition, a hoard of 31 coins of Antigonus

was found in the excavations of the Jewish Quarter of

Jerusalem (Avigad 1983:75, and Illus. 49-50; !AA

63301-63330, 63385).

To the north, west and south of Jerusalem, Antigonus'

coins were found in small numbers at Yodefat (1 coin;

unpublished, !AA 48853), Samaria (4 coins; Kirkman

1957:45 and p. 54), Bet She'an (1 coin; unpublished,

!AA 63671 ), Shoham ( 1 coin; unpublished, !AA 66599),

Khirbet el-' Aqd (two coins, one, along with a contemporary large module Herod coin, prepared for restriking

during the Bar Kokhba revolt, and the second, apparently also meant for that purpose; Kindler 1986-1987:

49-50, Nos. 15-17), Jaffa (1 coin; unpublished, !AA

61384), and Tel Qeshet (near Beer Sheva, Israel grid

1274 1052, l coin; unpublished stray find, !AA 59934).

However, to the east of Jerusalem, in the Judean

Desert, Antigonus' coins are plentiful relative to the

overall numbers of coins found there. Thus, already

before the 'Operation Scroll' survey, Antigonus' coins

were found in most of the late Hellenistic period sites

-------------

APPENDIX. HASMONEAN COINS FOUND IN THE CAVE OF THE WARRIOR

Yodcfal (I) e

Be! Shc'an(l)e

San1aria(4) e

Jaffa( I)

e Shoha1n {I J

Cavr of th('

Kh. cl-'Aqd (2) e

Cave (2)

(2?) 9

Jerusale1n

TdQcshr! (I)

::~:~~d Coins

Tulul Abu

cl-Alaiq (20)

(~~~~cshk~:(~1;:c1

Wadi

Mmabba'at(l)e

"

:0

\Varrior{9)e Cave 4 (I)

0

Hasmoncan 0 Cave 5 (2)

En Ged1 (2)

t:i

JJ)

30

--==--'km

Fig. Ap.l. Distribution of Antigonus' coins.

excavated there: at 'En Gedi (I coin fron1 a survey;

Mazar, Dothan, and Dunayewsky 1963:19; and 1 unpublished stray find, IAA 48937), 'Ein Feshkha (1 coin;

de Vaux 1973:66), Qumran (l coin; de Vaux 1973:1923), and Wadi Murabba'at (1 coin; de Vaux 1961:45,

No. "Mm. 274"). In addition, a hoard of 20 coins was

uncovered at Tulul Abu el-Alaiq (Netzer 1977:6, and p.

7, Fig. 9). Now, the finds from "Operation Scroll" have

almost doubled the number of sites in the Judean Desert

yielding coins of Antigonus: Besides the nine coins fron1

the Cave of the V/arrior, five coins of Antigonus were

found in three caves (one in Cave 4, the 'Column Cave';

two coins in Cave 5, the 'Loculi Cave'; t\VO or three in

the 'Hasmonean Cave'). In Cave 4 and the 'I-Iasinonean

Cave', the Antigonus coins are the latest coins found.

Seven caves examined in 'Operation Scroll' had either

coins of Alexander Jannaeus as their latest \Yell-identified coins, or it was found that any coins later than these

133

Jannaeus issues related to a completely different phase

of occupation of the cave. Jannaeus' coins ren1ained in

circulation until Herod's reign, after 37 BCE. A number

of these caves may also have been visited in the days of

Antigonus. That was probably the case in the 'Hasn1onean Cave' noted above, where, besides the t\0 certain Antigonus coins, there are coins of Hyrcanus I,

Alexander Jannaeus, and one uncertain Has1nonean

issue.

On the other hand, in Cave 5 the Antigonus coins

(of the penttah denomination) appear with coins of

Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BCE), and Herod (also

small denominations, after 37 BCE). Therefore it is

equally likely that the Antigonus coins (along with the

Jannaeus coins) were deposited there after 37 BCE, and

not between 40 and 37 BCE.

The character of the coin finds from 'Operation

Scroll' will be discussed in a later volume dealing with

nu1nisn1atic material fro1n a larger nu1nber of sites.

Nevertheless, for the purpose of placing the coins of the

Cave of the Warrior into their proper context, son1e

points are noteworthy. The overall picture presented by

the coin finds of 'Operation Scroll' is the lack of a

con1mon regional distribution pattern. Caves or co111plexes of caves had their individual, isolated, short-term

occupations. One cave will have only late Persian period

coins, while another will yield only coins from two years

of the Jewish War. Occasionally two (or more) distinct

periods of occupation are indicated by the coins, just

as two distinct periods of occupation \Vere found in the

Cave of the Warrior. Although many of the caves have

occupations dating to the period of Judean Desert nlonasticisn1, most of the other ti111e-fra111es encountered

were periods of strife in the country, and hence it is

easy to view those caves functionally as refuges for

people fleeing their homes - albeit in a number of different time periods (for this idea see Schwartz and Spanier

1992). The appearance of the coins of Antigonus in four

sites of 'Operation Scroll', along with the possibility

that the dates of other caves belong to this horizon, is

strong evidence that the period bet\veen 40 and 37 \Vas

one of the more important periods of upheaval, as far

as the region around Jericho \Vas concerned.

None of the large coins of Herod was found in 'Operation Scroll'. Only three were found elsewhere in the

vicinity, one at 'Ein Feshkha (de Vaux 1973:23, n. l,

and p. 66) and two at Masada (Meshorer 1989:87, No.

110; and an unpublished stray find, !AA 74504). This

s1nall nun1ber 111ay support the consensus that 1-Jerod's

large coins \Vere minted in Sa1naria, son1e\vhat n1ore

134

DONALD T. ARIEL

distant from the Jericho region than is Jerusalem, \Vhere

Antigonus' mint was located. Alternatively, it may

reinforce our contention that the people occupying the

Cave of the Warrior were not simply fleeing the battles

of 40-37 BCE but, rathe1; were organized supporters of

Antigonus, preparing attacks upon the Herodian forces

from their hiding places. It would then be less likely

that they could have coins of Herod in their possession.

On the other hand, one cannot categorically argue

that all the coins of Antigonus found in the region relate

directly to the presence of Antigonus' warriors. For example, the three coins (among 3,857 coins) identified in

the excavations at Masada should not be used as evidence for the actual presence of Antigonus' forces on

the summit. In fact these forces remained below the

summit, besieging Herod's family for a long period of

time. At the same time, the coins' appearance there

supports their circulation in the region.

CONCLUSIONS

The historical background (above) focused on the historian Josephus' frequent references to events which

took place in the Judean Desert between 40 and 37

BCE. When all the references are considered together

with the numismatic evidence presented here, the following conclusions can be offered:

1. While there were military activities in Galilee, and

along the Mediterranean coast, there \Vere also important engagements in the Jericho region. Jericho was a

place to be coveted. An indication of its contemporary

importance is evidenced by the fact that in 34 BCE,

after the battles were over, Cleopatra received the town

and its environs from Anthony, whereupon Herod leased

it back from her (Josephus, War i.18.5 (361); An!. xv.

4.2 (96)).

2. Jericho and its surroundings were an important center

of support for Antigonus (Stern 1995:269). His troops

were unimpeded in their pursuit and attack on Herod

and his family when they escaped Jerusalem. Antigonus'

forces were able to conduct a long siege of Masada,

although they were unsuccessful in preventing Herod

from later relieving his family. At the same time Josephus

portrays the local populace as pragmatic, rallying to

Herod mostly out of a wish to be on what appeared to

be the winning side (Josephus, War i.15.4 (293); An!.

xiv. 15.1 (398); see also War i.17.6 (335); Ant. xiv. 15.2

(458)). Antigonus' forces succeeded in their attack on

the convoy of provisions in the winter of 39/38, in their

a111bush against the Ro1nan forces under Joseph, and

later against Herod \vhen he returned to Jericho.

Herod's only activity in the Judean Desert in which,

according to Josephus, Herod did not encounter resistance, was the fortification of Alexandrium (Sartaba;

Josephus, War i.16.3 (308); Ant. xiv.15.5 (419)). But

Alexandrium lies much further north, not in the vicinity

of Jericho. In fact the interesting subject of the Judean

Desert palace/fortresses of the Hasmonean and Herodian kings does not relate to the nature of the occupation

in the caves. Those structures served as forts commanding views over main roads, as adn1inistrative and

agiicultural centers, and even as prisons and mausolea

(Tsafrir 1982:142), but not as staging areas for military

activity. Even Antigonus' siste1; after Antigonus' defeat,

remained sequestered in Hyrcania (until 32). This fortress served her as a refuge, and not a base for renewed

resistance (Josephus, War i.19.l (364)).

3. That Herod could find Jericho abandoned in the winter

of 39/38, and then repopulated in the summer of 38 is

consistent with and even reinforces the above picture. The

town people were able to find temporary refuge in the

vicinity. It is possible if not likely that they fled to the

many nearby caves in Wadi Makkukh and near Qarantal.

Josephus states: 'Antigonus issued orders throughout the

country to hold up and waylay the convoys. Acting upon

these orders, large bodies of men assembled above Jericho

and took up positions on the hills, on the lookout for the

conveyors of the supplies' (Josephus, War i.15.6 (300)).

In fact, there was probably little difference between the

able-bodied men of Jericho who hid in the those caves

and the warrior bands who attacked the convoy of winter

provisions on their way out of Jericho. Whether the

fighters were local townsmen who went up from Jericho

into hiding in the caves or whether they were out-oftowners, it is clear that they conducted classic guerilla

warfare against Herod's regular troops.

This picture may also hold for the fighting that took

place in the eaves which abound in the vicinity of Mt.

Arbel in the Galilee (Josephus, War i.16.2 (304-306),

i.16.4 (310-311); Ant. xiv. 15.4 (415-417), xiv. 15.5 (420428)). There are in that case no published numismatic

(or archaeological) finds to illustrate what transpired

there. At the same time, Josephus' description of the

caves, and Herod's treat1nent of them, confor111s 111ore

to their function as refuges than as staging areas for

guerilla attacks.

Parts of the Judean Desert were ideal for guerilla

warfare. Tsafrir (1982:122) comments that the Judean

Desert was employed as a 'base of mobilization' during

APPENDIX HASMONEAN COINS FOUND IN THE CAVE OF THE WARRIOR

the beginning of the Maccabbean movement. Nevertheless, the phenomenon we describe, although close, is

still different from the use of the desert as a mobilization

base. While Herod was on his way to Masada to free

his family, 'Antigonus sought to obstruct his advance

by posting ambuscades in suitable passes .. .'(Josephus,

135

War i.15.4 (294); see also Josephus, Ant. xiv. 15.2 (399)).

Antigonus clearly employed this relative advantage

whenever Herod's troops passed through. But such warfare at best can only achieve localized victories When

the battleground moved elsewhere, Antigonus' troops

lost that advantage, and were ultimately subdued.

Fig. Ap.2. The Has111onean coins.

CATALOGUE OF COINS

Mattathias Antigonus ( 40-37 BCE), Jerusalem

Obv. 0'11i'!'i1 i:::ini ?i:i. Ti1:>i1 il'nnb Cornucopias.

Rev. BACIJ\EQC ANTirONOV Within ivy wreath.

Obv. n i:ini ?i:i. F1:>il irnn1:) Cornucopia.

Rev. BACIJ\EQC ANTirONOV Within wreath.

1. Reg. No. 47, Kl6003.

i'E, '-, 12.21 gm, 23 mm. AJC 1:155, No. Ul.

5. Reg. No. 61, Kl601 l.

i'E, -+, 7.83 gm, 19 mm. AJC 1:157, No. V.

2. Reg. No. 60, K!6010.

i'E, j, 16.31 gm, 24 mm. Cf. AJC 1:155, No. U4.

Inscription: ;~m ;i Jc[,;i c']nni"

6. Reg. No. 57, Kl6007. Fig. Ap.2.

i'E, ,,- , 6.97 gm, 18 mm. AJC 1:158, No. V2.

3. Reg. No. 54, Kl6004. Fig. Ap.2.

i'E, j, 14.72 gm, 25 mm. Cf. AJC 1:155, No. U6.

Inscription: 0'/i1i' i:in 7i:i. Fl:> iPnni'J

4. Reg. No. 56, Kl6006. Fig. Ap.2.

i'E, j, 13.95 gm, 24 mm. AJC 1:155, No. U6.

7. Reg. No. 58, K!6008. Fig. Ap.2.

i'E, j, 7.55 gm, 19 mm. Cf. AJC 1:158, No. V3.

8. Reg. No. 55, K!6005. Fig. Ap.2.

i'E, /', 7.53 gm, 19 mm. AJC 1:158, No. V4.

9. Reg. No. 59, Kl6009.

i'E, ,...- , 7.36 gm, 19 mm. Cf. AJC 1:158, No. V7.

136

DONALD T. ARIEL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AJC I: Mcshorcr Y.

1982

Ancient Jell'ish Coinage. Dix Hills. NY.

Ahipaz N.

1996

Mattathias Antigonus: The Last Hasn1onean King

La\vrenz J.C.

1985

The Je\vish Coins. In G.C. Miles ed. The Coins fron1

theAnnenian Garden. Jn A.D. Tushinghain, Excavations in Jerusalen1 1961-1967, 1. Toronto. Pp. 156166.

in Jerusalem, in the Light of his Coins. Unpublished

MA se1ninar paper subn1ittecl to the Institute of

Archaeology of the Hebre\v University of Jerusalcn1

(Hebrew).

Mazar B., Dothan T., and Dunaye\vsky E.

1963

'Ein Gedi. Archaeological Excavations 1961-1962.

Yedior 27:1-133 (Hebrew).

An1iran R. and Eitan A.

1975

Excavations in the Jerusale1n Citadel. In Y. Yadin

ed. Jer11sale111 Revealed. Jerusale1n. Pp. 52-54.

Ariel D.T.

1982

A Survey of Coin Finds in Jerusalen1 (Until the End

of the Byzantine Period). Liher A111111us 32:273-326.

Ariel D.T.

990

Excaratio11s in the City of Da1 id Directed by Yigal

1

Shiloh IL l!nported Stt1111ped A111phora Ha11dles,

Coins~ f1/orked Bone and Ivo1y, and Glass (Qedem

30). Jerusale1n.

Avigad N.

Disco1ering Jerusale111. Nashville.

1983

Giller H.

1996

A Con1parative Study of Nu1nisn1atic Evidence fron1

Excavations in Jerusale1n. Liber A1111u11s 46:317-362.

Kanae! B.

1967

Notes on the Monetary Policy of the Has1nonean

Rulers. In A. l(indler ed. l11ter11ational 1Y11111is111atic

Convention, Jer11sale111, 27-31 Dece111ber 1963: The

Patrerns o_f 111011eta1y Del'elop111e11t in Phoenicia and

Palestine in Antiquity. Tel Aviv. P. 227

Kindler A.

1967

The Monetary Pattern and Function of the Je\vish

Coins. In A. Kindler ed. International N11111is111atic

Co1111e11tio11, Jer11sale111, 27-31 Decen1hcr 1963: The

Patterns (~f Alonctary Derelop111e11t in Phoenicia and

Palestine in Antiquit)'. Tel Aviv. Pp. 180-203.

Kindler A.

1986-87 Coins and Ren1ains fro1n a Mobile Mint of Bar

Kokhba at Khirbet el-''Aqd. Israel N11n1isn1atic

Journal 9:46-50.

Kirkman J.S.

1957

The Evidence of the Coins. In J.W Cro\vfoot, G.M.

Cro\vfoot, and l(.l\1. Kenyon, Sa111aria-Sehaste, III:

The Objects fron1 San1aria. London. Pp. 43-70.

Mazar B.

1971

The Exca1Ylfions in the Old City of Jcrusale111 1'./ear

the Te111ple Jvlount: Prelilninary Report of the Second

and Third Seasons 1969-1970. Jerusalen1.

Meshorer Y.

1989

A1asada I. The Yigael Yadin Exca11atio11s 1963-1965,

Final Report. Jerusalen1.

Meshorer Y

1990

Siege Coins of Judea. In I. Carradice ed. Proceedings

of the 10th International Congress a} Nun1isn1atics.

Lo11do11. Seplen1ber 1986. London. Pp. 223-229.

Netzer E.

1977

Winter Palaces of the Ju dean Kings at Jericho at the

End of the Second Temple Period. BA SOR 228:1-13.

SchD.rer E.

1973

The History of the Je111ish People in rhe Age of Je.\u:,

Chrisr (175 B.C.-135 A.D.), I. Revised and Edited

by G. Vermes and F. Millar. Edinburgh.

Schwartz J. and Spanier Y.

1992

On Mattathias the Hasmonean and the Desert of

San1aria. Cathedra 65:3-20 (Hebre\v; English

abstract, p. I 90).

Stern M.

1995

Has111011aea11 Judea in the f{e/lenistic I-Vorld Chapters

in Political HistoiJ: Edited by D.R. Sc\1\vartz.

Jerusale1n.

Tsafrir Y.

The Desert Fortresses of Judea in the Second Ten1ple

1982

Period. In L.l. Levine ed. The Jerusale111 Cathedra.

2. Jerusalen1. Pp. 120~139.

de Vaux R.

1961

Archeologie. Jn Benoit P., Milik J. T., and R. de

Vaux Discol'eries in rhe Judean Desert. II. Les Groll es

de Afurabb({/it. Oxford. Pp. 3-63.

de Vaux R.

Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Sch\veich

1973

Lectures of the British Acade1ny, 1957. London.

APPENDIX. HASMONEAN COINS FOUND IN THE CAVE OF THE WARRIOR

137

NOTES

1

The historical background for the reign of Mattathias Antigo nus, and some of the \York on the distribution of Antigonus'

coins, \Vere researched by Nili Ahipaz in an MA sen1inar paper

submitted to the Hebre\v University in 1996. My thanks to

her for pennission to use son1e of the n1aterial here.

1

For the best summary of the period, see Stern 1995:249~

274, Chap. 20: 'The Parthian Invasion of 40-38 BCE.'

Вам также может понравиться

- The Jerusalem Mint of Herod The Great: A Relative ChronologyДокумент26 страницThe Jerusalem Mint of Herod The Great: A Relative ChronologyMauro CocaОценок пока нет

- Chronology of TroyДокумент8 страницChronology of TroyeengelbriteОценок пока нет

- Underground' Money in An Outremer EstateДокумент17 страницUnderground' Money in An Outremer EstateLuis Arrieta PérezОценок пока нет

- Greek Coinages of Palestine: Oren TalДокумент23 страницыGreek Coinages of Palestine: Oren TalDelvon Taylor100% (1)

- Orodes IIДокумент16 страницOrodes IIMarkus OlОценок пока нет

- Hermonites HippopotamusДокумент25 страницHermonites HippopotamusEnokmanОценок пока нет

- Project Muse 26954-987876Документ17 страницProject Muse 26954-987876Ramdane Ait YahiaОценок пока нет

- NIEMEIER, W.D.+Archaic - Greeks - in - The - Orient. Textual and Arch. EvidenceДокумент22 страницыNIEMEIER, W.D.+Archaic - Greeks - in - The - Orient. Textual and Arch. EvidenceAnderson Zalewski VargasОценок пока нет

- A Short Note On The Circumcised Odomante PDFДокумент4 страницыA Short Note On The Circumcised Odomante PDFStefan StaretuОценок пока нет

- Herod The Great Another Snapshot of His Treachery?Документ14 страницHerod The Great Another Snapshot of His Treachery?MirandaFerreiraОценок пока нет

- Math3145 6817Документ4 страницыMath3145 6817whatisОценок пока нет

- Math6221 2825Документ4 страницыMath6221 2825rararariОценок пока нет

- Early Contacts Between Egypt, Canaaan and SinaiДокумент17 страницEarly Contacts Between Egypt, Canaaan and SinaiBlanca AmorОценок пока нет

- The Sanctuaries and Cults of Demeter On RhodesДокумент1 страницаThe Sanctuaries and Cults of Demeter On RhodesVentzislav KaravaltchevОценок пока нет

- CYPRUS in The Achaemenid PeriodДокумент16 страницCYPRUS in The Achaemenid PeriodYuki AmaterasuОценок пока нет

- The Arm of God Versus The Arm of Pharaoh)Документ11 страницThe Arm of God Versus The Arm of Pharaoh)igorbosnicОценок пока нет

- Eglon EgyptДокумент29 страницEglon EgyptEnokmanОценок пока нет

- EAH HieronymosofKardia PDFДокумент2 страницыEAH HieronymosofKardia PDFBenjamin DominicОценок пока нет

- Gonderian PeriodДокумент16 страницGonderian PeriodGossaОценок пока нет

- Proceedings of The Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society VOLUMES XXXVI-XXXVII (2004-2005)Документ23 страницыProceedings of The Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society VOLUMES XXXVI-XXXVII (2004-2005)Gurbuzer2097Оценок пока нет

- With Catharine Lorber An Early SeleucidДокумент25 страницWith Catharine Lorber An Early SeleucidBerna DurmuşОценок пока нет

- A Thunderbolt and Laurel On A Herod PhilДокумент13 страницA Thunderbolt and Laurel On A Herod PhiljayelОценок пока нет

- The Collapse of CivilizationsДокумент13 страницThe Collapse of CivilizationsscribОценок пока нет

- Chancey and PorterДокумент40 страницChancey and PortermarfosdОценок пока нет

- Mystery of The Dropa DiscsДокумент18 страницMystery of The Dropa DiscsMichael GreenОценок пока нет

- INDO - Parthian DynastyДокумент6 страницINDO - Parthian DynastyJehanzeb KhanОценок пока нет

- The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 19 Issue 3-4 1933 (Doi 10.2307 - 3854598) J. Grafton Milne - The Beni Hasan Coin-HoardДокумент4 страницыThe Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 19 Issue 3-4 1933 (Doi 10.2307 - 3854598) J. Grafton Milne - The Beni Hasan Coin-HoardDan AndersonОценок пока нет

- The Levant 1996-2001Документ33 страницыThe Levant 1996-2001Joaquín Porras OrdieresОценок пока нет

- Dating The Chedorlaomer's DeathДокумент45 страницDating The Chedorlaomer's DeathScott JacksonОценок пока нет

- Dating Fall of Dura EuropusДокумент25 страницDating Fall of Dura Europustemplecloud1100% (1)

- Alexander The Great and The Decline of MacedonДокумент13 страницAlexander The Great and The Decline of MacedonShahendaОценок пока нет

- A Late Bronze Age Egyptian Temple in Jerusalem - Gabriel Barkay - Israel Exploration Journal Vol 46 No 1-2 1996Документ22 страницыA Late Bronze Age Egyptian Temple in Jerusalem - Gabriel Barkay - Israel Exploration Journal Vol 46 No 1-2 1996solomonswisdomОценок пока нет

- Black Sea Piracy - TALANTA PDFДокумент8 страницBlack Sea Piracy - TALANTA PDFMaria Pap.Andr.Ant.Оценок пока нет

- Econ5252 1353Документ4 страницыEcon5252 1353SmrutirekhaОценок пока нет

- Philologus PildashДокумент25 страницPhilologus PildashEnokmanОценок пока нет

- Bijovsky INR 6 PDFДокумент15 страницBijovsky INR 6 PDFGabriela BijovskyОценок пока нет

- Prosopography of The Byzantine EmpireДокумент25 страницProsopography of The Byzantine EmpiresplijaОценок пока нет

- Black Sea PiracyДокумент15 страницBlack Sea PiracypacoОценок пока нет

- Jewish Coins of The Two Wars Aims and MeДокумент26 страницJewish Coins of The Two Wars Aims and MeMauroОценок пока нет

- 2017 The Earliest Known Sign of Tanit ReДокумент12 страниц2017 The Earliest Known Sign of Tanit RemacrillaalisaОценок пока нет

- Hist. Books II - Deuteronomic HistoryДокумент41 страницаHist. Books II - Deuteronomic HistoryManojОценок пока нет

- Thracian Units in The Roman ArmyДокумент11 страницThracian Units in The Roman ArmyDennisSabinovIsaevОценок пока нет

- Bosworth-1986-Alexander The Great and TheДокумент12 страницBosworth-1986-Alexander The Great and TheGosciwit MalinowskiОценок пока нет

- Judaea and Rome in Coins 65 BCE - 135 CE: D M. J N KДокумент26 страницJudaea and Rome in Coins 65 BCE - 135 CE: D M. J N KМарьяна СтасюкОценок пока нет

- Tribigild in Phrygia Reconsidering The RДокумент16 страницTribigild in Phrygia Reconsidering The REmre TaştemürОценок пока нет

- Mandell, Alice - I Bless You To YHWH and His Asherah PDFДокумент32 страницыMandell, Alice - I Bless You To YHWH and His Asherah PDFRobert AugatОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 193.140.239.12 On Sat, 01 May 2021 21:30:36 UTCДокумент8 страницThis Content Downloaded From 193.140.239.12 On Sat, 01 May 2021 21:30:36 UTCArmanОценок пока нет

- Maciej Czyz THE SYRIAN CAMPAIGN OF ROMANOS III ARGYROS IN 1030 CEДокумент34 страницыMaciej Czyz THE SYRIAN CAMPAIGN OF ROMANOS III ARGYROS IN 1030 CEamadgearuОценок пока нет

- Math3637 7914Документ4 страницыMath3637 7914Nata GamingОценок пока нет

- 8.political Decadence BeirutДокумент10 страниц8.political Decadence BeirutJordi VidalОценок пока нет

- A Forgotten Colony of LindosДокумент12 страницA Forgotten Colony of LindosEffie LattaОценок пока нет

- Aretas IV PhilopatrisДокумент4 страницыAretas IV Philopatrislmm58Оценок пока нет

- Prediction and Foreknowledge in Ezekiel'S Prophecy Against TyreДокумент17 страницPrediction and Foreknowledge in Ezekiel'S Prophecy Against TyreMarcos AurelioОценок пока нет

- Science6237 3615Документ4 страницыScience6237 3615Cheda Trisha DUОценок пока нет

- 185-196 - Oddy - The Christian Coinage of Early Muslim SyriaДокумент12 страниц185-196 - Oddy - The Christian Coinage of Early Muslim SyriaArcadie BodaleОценок пока нет

- Soc6099 372Документ4 страницыSoc6099 372Allen ReyesОценок пока нет

- The Achaemenid Army in A Near Eastern ContextДокумент6 страницThe Achaemenid Army in A Near Eastern Context626484201Оценок пока нет

- Greek Coinage / N.K. RutterДокумент56 страницGreek Coinage / N.K. RutterDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- Org of The US Inf BN 1940-45Документ58 страницOrg of The US Inf BN 1940-45Beagle75Оценок пока нет

- JOHANNES OECOLAMPADIUS: LIGHTHOUSE OF THE REFORMATION by John DyckДокумент5 страницJOHANNES OECOLAMPADIUS: LIGHTHOUSE OF THE REFORMATION by John DyckBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Those Solas in Lutheran TheologyДокумент2 страницыThose Solas in Lutheran TheologyBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Maori Pre1700 DBR Army ListДокумент2 страницыMaori Pre1700 DBR Army ListBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Battle of KaliszДокумент8 страницBattle of KaliszBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Wavell's Report On Operation CompassДокумент9 страницWavell's Report On Operation CompassBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Operation Compass by Peter ChenДокумент16 страницOperation Compass by Peter ChenBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- US Infantry Rifle Company Organization 1942 - 1945: A Resistant Roosters GuideДокумент2 страницыUS Infantry Rifle Company Organization 1942 - 1945: A Resistant Roosters GuideBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Italian Rifle CompanyДокумент1 страницаItalian Rifle CompanyBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- 6thaustralian1940 PDFДокумент2 страницы6thaustralian1940 PDFBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- FOW WWII British Infantry Painting GuideДокумент7 страницFOW WWII British Infantry Painting GuideBeagle750% (1)

- ADF Journal 203 - Operation Compass Article - CaveДокумент9 страницADF Journal 203 - Operation Compass Article - CaveBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Australian 6th Infantry Division December, 1940: x1 x14 x3 x3Документ2 страницыAustralian 6th Infantry Division December, 1940: x1 x14 x3 x3Beagle75Оценок пока нет

- 7 TH Armored 1940 Organisation For Use With Panzer BlitzДокумент1 страница7 TH Armored 1940 Organisation For Use With Panzer BlitzBeagle750% (1)

- FOW WWII Italian Infantry Painting GuideДокумент6 страницFOW WWII Italian Infantry Painting GuideBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- 4thindian1940 PDFДокумент1 страница4thindian1940 PDFBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Corps Troops WDF Task Organisation For Operation Compass With Panzer BlitzДокумент1 страницаCorps Troops WDF Task Organisation For Operation Compass With Panzer BlitzBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- FOW WWII US Airborne Painting GuideДокумент5 страницFOW WWII US Airborne Painting GuideBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- ADF Journal 203 - Operation Compass ArticleДокумент10 страницADF Journal 203 - Operation Compass ArticleBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- April 2019 Hangar Flying NewsletterДокумент7 страницApril 2019 Hangar Flying NewsletterBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Hangar Flying Newsletter Feb 2019Документ6 страницHangar Flying Newsletter Feb 2019Beagle75Оценок пока нет

- Ancient City FightДокумент5 страницAncient City FightBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Narrative of A Voyage To Maryland 1634 by FR WhiteДокумент116 страницNarrative of A Voyage To Maryland 1634 by FR WhiteBeagle75Оценок пока нет

- Alex J Gregg Vs Ariana GrandeДокумент22 страницыAlex J Gregg Vs Ariana GrandeDigital Music NewsОценок пока нет

- Screenshot 2023-11-04 at 7.44.48 PMДокумент1 страницаScreenshot 2023-11-04 at 7.44.48 PMLeonardo FonsecaОценок пока нет

- HD325-6 مانیتور پانل دامپتراک کوماتسوДокумент21 страницаHD325-6 مانیتور پانل دامپتراک کوماتسوMilad RahimiОценок пока нет

- The Charge of The Light Brigade by Lord Alfred TennysonДокумент4 страницыThe Charge of The Light Brigade by Lord Alfred Tennysonsaifulazwan_19Оценок пока нет

- Exercise Guide Torus 408Документ62 страницыExercise Guide Torus 408charnybrОценок пока нет

- Nityananda SongsДокумент32 страницыNityananda SongsMann Mahesh HarjaiОценок пока нет

- Streetphotography by Daniel HoffmannДокумент94 страницыStreetphotography by Daniel Hoffmannhancillo100% (1)

- Danztrack 2022 Battle MechanicsДокумент4 страницыDanztrack 2022 Battle MechanicsKIM MARLON GANOBОценок пока нет

- 40 Best Romantic Song Lyrics To Share With Your Partner This Valentine's DayДокумент21 страница40 Best Romantic Song Lyrics To Share With Your Partner This Valentine's DayJennifer AmionОценок пока нет

- Barco UniSee 500 NitsДокумент3 страницыBarco UniSee 500 NitsBullzeye StrategyОценок пока нет

- SAOY Final Script MULTIST PDFДокумент4 страницыSAOY Final Script MULTIST PDFJamie ArellanoОценок пока нет

- Food Distribution and Food ServiceДокумент32 страницыFood Distribution and Food ServiceAngelo PalmeroОценок пока нет

- KBL-R 17810-1 - 230630 - 145525Документ107 страницKBL-R 17810-1 - 230630 - 145525roqueОценок пока нет

- Chordu Guitar Chords Generación 12 Al Que Está Sentado en El Trono Marcos Brunet Cover Chordsheet Id - yGSLKbpFLAUДокумент4 страницыChordu Guitar Chords Generación 12 Al Que Está Sentado en El Trono Marcos Brunet Cover Chordsheet Id - yGSLKbpFLAUAmilcar SerranoОценок пока нет

- Ball Bearing Classification PDFДокумент5 страницBall Bearing Classification PDFshihabjamaan50% (2)

- TVДокумент160 страницTVEddy CedilloОценок пока нет

- Unit 3Документ28 страницUnit 3Abhiram TSОценок пока нет

- English GrammarДокумент3 страницыEnglish GrammarPaige RicaldeОценок пока нет

- Netscaler 9 CheatsheetДокумент1 страницаNetscaler 9 CheatsheetfindpraxtianОценок пока нет

- Business Plan Template From ShopifyДокумент31 страницаBusiness Plan Template From ShopifyGhing-Ghing ZitaОценок пока нет

- Cesar R Torres Olim Pics 1922Документ9 страницCesar R Torres Olim Pics 1922Alonso Pahuacho PortellaОценок пока нет

- TCS - UnclaimedDiv - 1st - 2010-11-On-2012Документ1 146 страницTCS - UnclaimedDiv - 1st - 2010-11-On-2012AartiОценок пока нет

- Obs LogДокумент9 страницObs LogSusan WiseОценок пока нет

- 2019 Colloquium Draft March 12Документ33 страницы2019 Colloquium Draft March 12Jessica BrummelОценок пока нет

- Macromechanics of A LaminateДокумент45 страницMacromechanics of A LaminateAvinash ShindeОценок пока нет

- Unidad: ¡Aprende Inglés!Документ4 страницыUnidad: ¡Aprende Inglés!Andrea Peña TorresОценок пока нет

- I. Multiple Choice: Directions: Read and Analyze The Statement Carefully. Choose The Correct Answer in Your Answer SheetДокумент2 страницыI. Multiple Choice: Directions: Read and Analyze The Statement Carefully. Choose The Correct Answer in Your Answer SheetMolash Leiro100% (1)

- Marteau Bti Bxr100Документ215 страницMarteau Bti Bxr100Anonymous iOiwomgEcBОценок пока нет

- (YUQI) - 'Flowers Miley Cyrus' (Cover) - YouTДокумент1 страница(YUQI) - 'Flowers Miley Cyrus' (Cover) - YouTjoy.huang.zhangОценок пока нет

- Community Blend Issue 3Документ12 страницCommunity Blend Issue 3bsb_fcpОценок пока нет