Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Forestal Guarani S.A. v. Daros Int'l., Inc

Загружено:

AdelinaIrimiaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Forestal Guarani S.A. v. Daros Int'l., Inc

Загружено:

AdelinaIrimiaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

INTERNATIONAL CONTRACT LAWCHOICEOF-LAW ANALYSIS APPLIES WHEN SIGNATORY

NATIONS ADOPT OPPOSING ORAL CONTRACT

PROVISIONS UNDER THE CISGFORESTAL

GUARANI S.A. V. DAROS INTL., INC., 613 F.3D 395

(3D CIR. 2010).

The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the

International Sale of Goods (CISG) governs contract formation

between parties of signatory nations and grants a right of action for

breach of contract.1 Article 11 of the CISG allows signatory nations

to create enforceable oral contracts.2 Signatory nations may opt out

of Article 11 obligations by making an Article 96 reservation or

declaration.3 In Forestal Guarani S.A. v. Daros Intl., Inc.,4 the

United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit considered the

enforceability of an oral contract created by parties of signatory

nations with divergent implementation of the CISG.5 The Third

Circuit held that when one partys country of incorporation has made

an Article 96 reservation and the other partys state has not, and

neither the text nor principles of the CISG apply, the court must

undertake a choice-of-law analysis to determine which forums law

1. United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of

Goods art. 45, Apr. 11, 1980, 52 Fed. Reg. 6262 (Mar. 2, 1987), 1489 U.N.T.S. 3

[hereinafter CISG]; see BP Oil Intl, Ltd. v. Empresa Estatal Petroleos de Ecuador,

332 F.3d 333, 336 (5th Cir. 2003) (citing Delchi Carrier v. Rotorex Corp., 71 F.3d

1024, 1027-1028 (2d Cir. 1995)).

2. CISG, supra note 1, art. 11. Under Article 11, [a] contract of sale need not

be concluded in or evidenced by writing and is not subject to any other

requirement as to form. It may be proved by any means, including witnesses. Id.

3. CISG, supra note 1, art.96.

A contracting State whose legislation requires contracts of sale to be

concluded in or evidenced by writing may at any time make a declaration . .

. that any provision of article 11 . . . of this Convention, that allows a

contract of sale or its modification or termination by agreement or any

offer, acceptance, or other indication of intention to be made in any form

other than in writing, does not apply where any party has his place of

business in that State.

Id.

4. 613 F.3d 395, (3d Cir. 2010).

5. Id. at 400 (determining CISGs text and provisions inapplicable concerning

writing requirements).

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

applies.6 Only after such analysis would the court apply that forums

law to adjudicate issues of contract formation and breach.7

In 1999, Daros International, Inc., an export-import company

based in New Jersey, entered into a verbal contract with the

Argentinean manufacturing company Forestal Guarani S.A. for

wooden finger-joints.8 Daros paid Forestal $1,458,212.35 for fingerjoints which, according to Forestal, were valued at $1,857,766.06.9

Forestal filed a breach of contract claim in the Superior Court of

New Jersey in April 2002 for the remaining balance due because it

believed the oral contract specified the greater amount.10 Daros

subsequently removed to federal court, naming the CISG as the

international treaty on which the subject matter jurisdiction of the

federal court was based.11

The District Court denied Daros 2005 summary judgment

motion, determining that there were genuine issues of material fact

concerning the contracts existence.12 After briefing in 2008, the

District Court granted Daros motion for summary judgment, finding

the oral contract to be invalid.13 The Third Circuit disagreed,

6. Id. at 395.

7. Id. The court remanded the case to determine whether Argentinean or New

Jersey law governs, suggesting summary judgment, or some other pretrial

disposition, including a venue transfer, may be appropriate on a more developed

record. Id. at 403. Generally, courts may use choice-of-law provisions to settle

international sales contract disputes. See Henry Mather, Choice of Law for

International Sales Issues Not Resolved by the CISG, 20 J.L. & COM. 155, 167

(2001)(noting choice-of-law process may resolve some issues generally governed

by the CISG). Before a court applies a choice-of-law analysis, however, it must

first find the issue cannot be resolved by the CISGs general principles. Id. at 157158 (characterizing one CISG principle as facilitating international trade, through

adjudicative methods such as recognizing parties freedom to contract).

8. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 396. A finger joint is a woodworking joint with cut

notches in the shape of fingers, commonly used to create a strong connection

between two pieces of wood. GARY ROGOWSKI, THE COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED

GUIDE TO JOINERY 123 (2002).

9. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 396; see also Forestal Guarani S.A. v. Daros Intl,

Inc., No. 03-4821, 2008 WL 4560701, at *1 n.2 (D.N.J. Oct. 8, 2008) (noting

actual figure owed was $399,553.71).

10. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 396. Daros argued it had properly compensated

Forestal. Id.

11. Id. Daros filed for removal under 28 U.S.C. 1331(a), which grants

federal district courts subject matter jurisdiction for civil actions arising under a

treaty of the United States. Forestal, 2008 WL 4560701 at *1 (noting courts basis

for jurisdiction).

12. See Forestal, 2008 WL 4560701 at *3 (finding Forestal did not provide

evidence of a contract).

13. Forestal, 2008 WL 4560701, at *5. (holding plaintiffs breach of contract

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

holding that the CISG does not expressly settle whether a party can

sustain a breach of contract claim for an oral contract when only one

partys country of incorporation has made an Article 96

Declaration.14 Further, the principles of the CISG do not facilitate

adjudication.15 Under these circumstances, the Third Circuit decided

that choice-of-law rules for the forum state must govern, given the

CISGs reference to the rules of private international law.16

The origins of the CISG lie in decades of international drafting

claim must fail because no written contract existed). The District Court held the

contract between Daros and Forestal was invalid for two reasons: first, having used

an Article 96 reservation to the CISG, Argentinean law required contracts to be in

writing and thus any international oral agreement was not binding; and second,

absent an oral agreement, Forestal failed to produce sufficient evidence of a

contract with Daros. Id. at 4.

14. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 400 (stating Argentinas choice to reject certain

CISG provisions renders CISG default rules inapplicable). In his dissenting

opinion, Judge Cowen writes that the Third Circuit should not have addressed the

issue of choice-of-law analysis because the issue had not been properly preserved

and the parties did not brief the applicability of a choice-of-law analysis. Id. at

403-04 (Cowen, J., dissenting). The dissent concludes that the courts

consideration of these complex and novel CISG and choice-of-law issues would

therefore be inappropriate. Id. at 404.

15. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 400. Under Article 7(2):

Questions concerning matters governed by this Convention which are not

expressly settled in it are to be settled in conformity with the general

principles on which it is based or, in the absence of such principles, in

conformity with the law applicable by virtue of the rules of private

international law.

CISG, supra note 1, art 7(2); see also COMMENTARY ON THE U.N. CONVENTION ON

THE INTERNATIONAL SALE OF GOODS (CISG) 102 (Peter Schlechtriem & Ingeborg

Schwenzer eds., 2d ed. 2005) [hereinafter COMMENTARY ON CISG] (clarifying

two-step process of gap-filling: using CISGs uniform rules and general

principles); BRUNO ZELLER, CISG AND THE UNIFICATION OF INTERNATIONAL

TRADE LAW, 64-65 (2007) (explaining where gap or exclusion of a matter within

the CISG exists, Article 7(2) provides guidance); CAMILLA BAASCH ANDERSEN,

UNIFORM APPLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL SALES LAW: UNDERSTANDING

UNIFORMITY, THE GLOBAL JURISCONSULTORIUM AND EXAMINATION AND

NOTIFICATION PROVISIONS OF THE CISG 127 (2007)(noting CISGs general

principles in Article 7(2) embody spirit of convention).

16. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 400 (determining American courts may utilize

choice-of-law process to determine law governing transactions with non-signatory

state). See Mather, supra note 6, at 157 (explaining when CISG general principles

cannot resolve issue, courts may utilize choice-of-law analysis); COMMENTARY ON

CISG, supra note 15, at 109 (stating if gap-filling fails, courts may apply domestic

law as a last resort); Zeller, supra note 15, at 65 (explaining if CISG principles

or text exclude matters, courts may use domestic law). [If] a matter is explicitly

excluded . . . a domestic law needs to be consulted to resolve the issue, hence

invoking conflict of law issues. Zeller, supra note 15, at 65.

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

and cooperation.17 Today, the CISG applies to contracts of sale of

goods between parties that are incorporated in different contracting

states.18 Under Article 7(1), contracting states should regard the

CISGs goals to promote uniformity and observe good faith in

international trade.19 Good faith includes a standard of

reasonableness.20 Finally, the CISG governs contract formation,

including the rights and obligations within that formation, and is

adopted into a countrys domestic law upon ratification.21

17. Camilla Baasch Andersen, The Uniform International Sales Law and the

Global Jurisconsultorium, 24 J. LAW & COM. 159, 160-161 (2005)(stating CISGs

predecessors are founded in 1964 Hague Conventions Uniform Law for

International Sale and Uniform Law of Formation). The result of thirteen years of

drafting, the current CISG provides a uniform method to govern international

sales. Id. at 160. See COMMENTARY ON CISG, supra note 15, at 1 (tracing roots of

international sales law to international committees and commissions beginning in

the 1930s); Michael A. Tessitore, The U.N. Convention on International Sales and

the Sellers Ineffective Right of Reclamation Under the U.S. Bankruptcy Code, 35

WILLAMETTE L. REV. 367, 367 (1999) (explaining CISG objective as providing

uniform international law concerning sales of goods).

18. CISG, supra note 1, art. 1(1)(a); see Standard Bent Glass Corp. v.

Glassrobots Oy, 333 F.3d 440, 444 n.7 (3d Cir. 2003) (noting CISGs applicability

to sale of goods between parties whose countries of incorporation are signatories);

Zapata Hermanos Sucesores, S.A. v. Hearthside Baking Co., 313 F.3d 385, 387

(7th Cir. 2002) (discussing international contract law among CISG signatory

nations). The United States and Argentina are signatory states of the CISG. CISG:

Table of Contracting States,

http://www.cisg.law.pace.edu/cisg/countries/cntries.html (last visited Jan. 18,

2011); see JOHN HONNOLD, UNIFORM LAW FOR INTERNATIONAL SALES UNDER THE

1980 UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION 57 (Kleuwer Deventer ed., 1982) (harkening

to Conventions history for its applicability to international sales).

19. CISG, supra note 1, art. 7(1). In the interpretation of this Convention,

regard is to be had to its international character and to the need to promote

uniformity in its application and the observance of good faith in international

trade. Id. See Alejandro M. Garro, Reconciliation of Legal Traditions in the U.N.

Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, 23 INTL LAW. 443,

465-68 (1989) (detailing divergent opinions concerning good faith language

while drafting Article 7); Asante Technologies, Inc. v. PMC-Sierra, Inc., 164 F.

Supp. 2d 1142, 1151 (N.D. Cal. 2001) (stating CISGs expressly stated goals to

promote international trade through uniform international contract law).

20. JOSEPH LOOKOFSKY, UNDERSTANDING THE CISG IN THE U.S.A.:

COMPACT GUIDE TO THE 1980 UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON CONTRACTS FOR

THE INTERNATIONAL SALE OF GOOD 19 (1995)(noting this general principle may

meet many needs); see Andersen, supra note 16, at 102-03 (characterizing

reasonableness as cornerstone of all legal systems despite subjectivity); Nathalie

Hoffman, Interpretation Rules and Good Faith as Obstacles to the U.K.s

Ratification of the CISG and the Harmonization of Contract Law in Europe, 22

PACE INT'L L. REV. 145, 168 (2010)(determining good faith important gap-filling

principle for matters governed by, but not expressly settled in the CISG).

21. CISG supra note 1, art. 4(a); see BP Oil Intl, 332 F.3d at 337

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

A signatory nation may choose to comply with or opt out of

several provisions of the CISG.22 For instance, Article 11 governing

formation of a contract under the CISG does not require contracts to

be in writing, and Article 29 allows parties to prove modifications to

an oral contract.23 Signatory countries, however, may require parties

to memorialize contracts through writing by making an Article 96

declaration, thereby opting out of Part II and Articles 11 and 29.24

When two signatory countries have adopted opposing

provisions, the courts must apply CISGs underlying principles in

accordance with Article 7(2) to reconcile the discrepancy.25 The

(determining nations ratification of CISG necessarily incorporates treaty as part

of [that] nations domestic law); Lookofsky, supra note 19, at 6 (explaining

Article 1(1) mandates courts apply CISG when parties whose places of business lie

in different contracting states); Chateau Des Charmes Wines, Ltd. v. Sabate

U.S.A., Inc., 328 F.3d 528, 530 (9th Cir. 2003) (stating CISG governs question of

contract formation concerning forum selection clauses in breach of oral contract).

22. CISG, supra note 1, art. 7(1); see Garro, supra note 18, at 446 (declaring

states may declare ratification of CISG in full or in part); BP Oil Intl, 332 F.3d at

337 (asserting CISGs opt-out policies promote treatys goals of uniformity and

good faith in international trade).

23. CISG, supra note 1, art. 29. (1) A contract may be modified or

terminated by the mere agreement of the parties, and (2) A contract in writing

which contains a provision requiring any modification or termination by agreement

to be in writing may not be otherwise modified or terminated by agreement.

However, a party may be precluded by his conduct from asserting such a provision

to the extent that the other party has relied on that conduct. Id. See Garro, supra

note 19, at 461 (asserting contracting states may apply choice-of-law rules to

determine whether written contract is necessary).

24. CISG, supra note 1, art. 96.

A Contracting State whose legislation requires contracts of sale to be

concluded in or evidenced by writing may at any time make a declaration in

accordance with article 12 that any provision of article 11, article 29, or

Part II of this Convention, that allows a contract of sale or its modification

or termination by agreement or any offer, acceptance, or other indication of

intention to be made in any form other than in writing, does not apply

where any party has his place of business in that State.

Id. Further, Article 12 reinforces the principle that provisions in Part II and

Articles 11 and 29 do not apply when a party is incorporated in a contracting state

which has made an Article 96 declaration. Id. In the drafting process, the

reservation granted by Article 96 was a compromise between certain socialist

countries, which required written contracts, and those countries which honored oral

contracts. See Garro, supra note 19, at 461.

25. CISG, supra note 1, art. 7(2). Questions concerning matters governed by

this Convention which are not expressly settled in it are to be settled in conformity

with the general principles on which it is based or, in the absence of such

principles, in conformity with the law applicable by virtue of the rules of private

international law. Id. See supra note 13 and accompanying text (discussing

elusiveness of CISGs general principles).

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

CISG controls in situations even when a reconciliation between

provisions may be needed; there is no consensus, however, among

the United States or international courts as to how the CISGs

principles may resolve disputes effectively.26

In Forestal Guarani S.A. v. Daros Intl., Inc., the United States

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit determined a choice-of-law

analysis would apply when disputes between parties of signatory

states with different CISG provisions could not be resolved through

the CISGs text or general principles.27 Given the sparse

jurisprudence on this issue, the court relied on scholars expertise to

inform its decision.28 The court acknowledged that the CISG

governs this contract dispute generally, but could not resolve whether

a contract or the terms of the contract had been formed.29 After

applying the CISGs plain language, it found Articles 11 and 96 did

26. See 28 U.S.C. 1652 (2006); David Frish, Commercial Common Law, the

United Nations Convention on the International Sale of Goods, and the Inertia of

Habit, 74 TUL. L. REV. 495, 507 (1999) (asserting lack of reliable CISG gap-fillers

resulted from drafters regard for many legal systems); Mather, supra note 7

(highlighting gaps and choice-of-law provisions); Louis F. Del Duca,

Implementation of Contract Formation Statute of Frauds, Parol Evidence and

Battle of Forms CISG Provisions in Civil and Common Law Countries, 25 J.L. &

COM. 133, 146 (2005) (discussing one courts ruling that binding contract was

formed with oral agreement of kind, quantity, and price of goods); Zhejiang

Shaoxing Yongli Printing & Dyeing Co. v. Microflock Textile Group Corp., No.

06-22608, 2008 WL 2098062 at *2 (S.D.Fla. May 19, 2008) (holding invoices and

packing slips constitute an agreement between parties of contracting states with

divergent CISG provisions); see also Franco Ferrari, Writing Requirements: Article

11-13, in THE DRAFT UNCITRAL DIGEST AND BEYOND: CASES, ANALYSIS AND

UNRESOLVED ISSUES IN THE U.N. SALES CONVENTION 213-14 (Franco Ferrari et al.

eds., 2005) (explaining CISGs legislative history corroborates view that rules of

private international law should govern when one contracting state has made an

Article 96 declaration and one has not).

27. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 396.

28. See id. at 399. The court found there is [a]lmost no case law from U.S.

courts concerning this issue. Id. Likewise, courts in other signatory nations have

no single approach to this issue. Id. (citing to the UNICITRAL Digest of Case

Law on the CISG outlining conflicting approaches); see Lookofsky, supra note 20,

at 22 (referring to Article 7(2) as a method either to fill any CISG gap or to

resort to domestic law); Larry A. DiMatteo et al., The Interpretive Turn in

International Sales Law: An Analysis of Fifteen Years of CISG Jurisprudence, 24

NW J. INTL L. & BUS. 299, 315 (2004) (qualifying CISG as studied ambiguity or

compromise that leads to many textual gaps); COMMENTARY ON CISG, supra note

15, at 169 (rejecting view reservation states rules should prevail over nonreservation state).

29. Forestal, 613 F. 3d at 397; see Zapata Hermanos, 313 F.3d at 388 (stating

when issue not mentioned in CISGs text, by the terms of the Convention itself

the matter must be left to domestic law). But see Zhejiang Shaoxing, 2008 WL

2098062 at *3 (holding contract is valid at acceptance).

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

not resolve the issue.30 Next, the court applied the first clause of

Article 7(2) which mandates applying general principles when the

CISG does not expressly settle a conflict.31 Finding no applicable

general principles, the court invoked the second half of Article 7(2)

and determined application of private international law the most

appropriate manner of adjudication.32

In its reasoning, the Third Circuit contemplated two possible

approaches: first, that courts might apply a choice-of-law analysis

based on principles of private international law; and second, that a

contract between Argentinean and American companies must be in

writing because Argentina, a signatory nation with an Article 96

declaration, requires international contracts governed by the CISG to

be in writing.33 Having established these two alternatives, the court

determined the first approach was proper because neither the plain

text nor the principles of the CISG expressly settled the issue.34 The

court concluded this approach was consistent with the CISG, given

30. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 397. The court further explained, [t]he United

States has not made an Article 96 declaration, so Article 11 governs contract

formation in cases involving a United States-based litigant and a litigant based in

another non-declaring signatory state. Argentina, however, has made a declaration

under Article 96. Id. at 399.

31. Id. at 400 (determining the CISGs principles inapplicable to its

provisions concerning writing requirements). The Court further stated, [w]e do

not believe that we can answer the question presented here based on a pure

application of those principles alone. Id.

32. Id. at 398-400 (asserting we fail to see how [CISGs principles] inform

question whether Forestals contract claim may proceed).

33. Id. The court designates the former school of thought the clear majority

view and the second the minority view. Id. at 399-400. The District Court had

reasoned that if the contract is silent as to choice of law, the CISG applies if both

parties are located in signatory nations. Forestal, 2008 WL 4560701 at *3. The

Third Circuit parted with the district court by holding that a countrys Article 96

declaration does not automatically translate into the necessity of a written contract.

Forestal, 613 F.3d at 400 n.9.

34. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 400. The court also discussed the potential

ramifications if the minority view were to prevail: all courts would encounter the

difficult question of what constitutes an adequate writing. Id. at 400 n.9 (asking

whether writing constitutes a professionally drafted document . . . [or] scribbling

on the back of a napkin). Explaining its reasoning for departing from the District

Courts analysis, the court stated,

[t]he District Court evidently presumed that a countrys Article 96

declaration automatically translates into a requirement that a contract be in

writing. But . . . the CISG does not say as much. It says only that its

freedom-from-form requirements do not apply where a country has made

an Article 96 declaration.

Id. at 401 n.9.

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

Article 7(2)s reference to the rules of private international law.35 In

so ruling, the Third Circuit established a standard that disregards the

CISGs principles, potentially undermining the creation of a uniform

international sales law.36

Faced with this unusual dispute, the Third Circuit properly ruled

the CISG applied to this contract.37 The CISG became part of

domestic law when the U.S. ratified it. 38 Additionally, the court

grounded its analysis of the case in the CISGs text, in accordance

with the prevailing analysis for interpreting international treaties.39

The Third Circuit should have looked to Article 7(2) and

conducted a more thorough analysis of the CISGs general

principles.40 Additionally, the court might have seized the

opportunity to read the CISGs principles of good faith and party

autonomy expansively, as had the District Court.41 A choice-of-law

35. See Forestal, 613 F.3d at 400 (stating court must consider choice-of-law

rules of the forum state).

36. See Anderson, supra note 14, at 3 (discussing importance of uniformity in

applying CISG, which spans six continents and . . . very different legal cultures).

The courts approach may likely apply only to this fact-specific case. Although

Forestal failed to pursue choice-of-law analysis in District Court, the majority

considered it unfair to apply the waiver doctrine to a party that did not participate

in the appeal. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 403 n.11.

37. See CISG supra note 1, art. I(1)(a)(declaring CISG applies to contracts for

sale of goods between contracting states with places of business in different states);

Forestal, 613 F.3d at 400 (discussing treatment of issues governed by CISG but

not specifically addressed).

38. Zeller, supra note 14, at 41 (explaining domestic choice of laws rule will

still decide which municipal law . . . fills gaps left by CISG in absence of general

principles).

39. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 398; see e.g. Abbott v. Abbott, 130 S.Ct. 1983, 1990

(2010) (directing court to treatys text to resolve the dispute); Medellin v. Texas,

552 U.S. 491, 506 (2008)(holding interpretation of a treaty begins with the text).

40. See Ferrari, supra note 26, at 161 (declaring the most important general

CISG principle as party autonomy); COMMENTARY ON CISG, supra note 15 at 104

(listing numerous general principles commonly referenced, including autonomy of

parties and freedom of form); Andersen, supra note 15, at 128 (listing general

principles as cooperation, duty to disclose, reasonableness, and respect for

international traders); Zeller, supra note 15, at 86 (arguing that a personal choice

must be made to either embrace a uniform international law or remain firmly

planted in domestic law.).

41. See Lookofsky, supra note 20, at 22 (stating courts following restrained

approach utilize domestic law but activist courts use Article 7(2) to fill textual

gaps); Zeller, supra note 15, at 43 (maintaining courts and arbitrators should apply

private international law only as a last resort); COMMENTARY ON CISG, supra note

15, at 96 (arguing that liberal interpretation of Article 7 will adjust the Convention

to new developments in international sales).

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

analysis may frustrate the goals of the CISG.42 Uniformity in

international sales, though still not the norm, would increase

certainty in the CISGs interpretation.43 Likewise, the court could

have provided clear guidance to other signatory states by strictly

adhering to Argentinas Article 96 declaration and finding no legal

contract was formed by the two companies agreement.44

Ultimately, the courts delineation of two modes of analysis

seems to unduly strain their plain reading of the text of the CISG.45

The ruling contradicts the CISG principles stated in its preamble,

which declares the drafters of the CISG wished to adopt a uniform

sale of goods to contribute to the removal of legal barriers in

international trade.46 Notwithstanding the courts

42. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 404 (Cowen, J., dissenting). Judge Cowen writes

that although the court should not reach the merits of the case at this time, he does

not agree that the choice-of-law analysis is required because such an approach

appears to be at odds with the CISG itself. Id. Courts have held that the CISG

automatically applies to international sales contracts between parties from different

contracting states unless the parties agree to exclude the application of the CISG,

as stated in Article 6. See Zhejiang Shaoxing, 2008 WL 2098062 at *2 (stating the

applicability of the CISG under Article 6).

43. CISG supra note 1, Art. 7(1). Article 7(1) states a court should interpret

the CISG in accordance with its international character and . . . the need to

promote uniformity in its application and the observance of good faith in

international trade. Id.; see Hofmann, supra note 20, at 154 (maintaining

importance of courts application of similar interpretations of CISG to avoid

varying results).

44. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 400 n.9. The Court designates this view as the

minority and states the District relied upon it in its determination. Id. The court

rejects this minority view, stating [w]e have concluded, however, that such a

position is wrong as a matter of law. Id. at 402. The court considered resolving

the issue at hand, but declined without full briefing from the parties. Id. Rather,

the court considered applying both New Jersey and Argentinean law to Forestals

claim to test its viability, but decided it unwise . . . to venture into this choice-oflaw thicket. Id.

45. See Forestal, 613 F.3d 395 (delineating analysis to apply CISG to narrow

group of cases); see CISG supra note 1 (outlining rules plainly to simplify uniform

application internationally).

46. CISG supra note 1, preamble. The CISGs preamble offers the policies of

creating this international agreement, stating the adoption of uniform rules which

govern contracts for the international sale of goods and take into account the

different social, economic and legal systems would contribute to the removal of

legal barriers in international trade and promote the development of international

trade. Id. Because Forestal has told the court of an existing legal barrier, being

unable to remove business documents from Argentina, the court might have

considered applying the minority analysis, or could have found a valid contract

based on evidence of acceptance and delivery. See Forestal, 613 F.3d at 404

(Cowen, J., dissenting). One reason Judge Cowens views differ from the

majoritys is that given the plain language of this international treaty, its structure,

SUFFOLK TRANSNATIONAL LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 34, BOOK 1

acknowledgement that the posture of the case drove their judgment,

the court could have relied less heavily on scholarship and more

directly on the CISGs text and extensive drafting history.47 Their

ruling provides a standard to other courts to utilize a choice-of-law

analysis, where domestic law, rather than international sales law,

dominates.48

In Forestal Guarani S.A. v. Daros Intl., Inc., the United States

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit considered whether the CISG

governed a contract dispute between signatory nations which adopted

conflicting CISG provisions. In deciding to apply choice-of-law

analysis because the CISGs text and principles were determined

inapplicable, the court narrowed the scope of the CISGs

applicability and frustrated its objective to create a body of uniform

international sales law.

Jeannette Sedgwick

and its purposes, a written contract is required where, as here, one of the relevant

countries has exercised its right to make an Article 96 declaration. Id.

47. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 402 (stating [o]ur conclusion that remand is

appropriate is also driven by the [cases] posture); see Zhejiang Shaoxing, 2008

WL 2098062 at *3 (finding changes to written contract not evidenced by writing

and therefore unenforceable). But see Zapata Hermanos, 313 F.3d at 388 (holding

choice-of-law analysis governs issue of attorneys fees because issue not

mentioned in CISG). The CISGs legislative history could have resulted in a more

expansive reading. See COMMENTARY ON CISG, supra note 15 at 169-70

(discussing history, significance, and scope of Article 12); Lookofsky, supra note

20 (analyzing CISG from variety of angles). Moreover, the court may have found

it reasonable that a contract was formed: Daros paid Forestal in exchange for

finger-joints, and Forestal has submitted invoices and an accountants certification

to support its claim. Forestal, 613 F.3d at 402.

48. Andersen, supra note 15, at 130 (decrying the second prong of Article

7(2) as outside the scope . . . of uniformity [because allows] any law . . . to solve

an issue); see also Honnold, supra note 18, at 61 (explaining adaptation and

development [of the Convention] are encouraged by good faith in international

trade). Courts should utilize CISG general provisions to minimize the confusion

inherent in conflicts rules and avoid the uncritical and wooden application of

domestic law. Id. at 133. See Zeller, supra note 15, at 106 (concluding the

Conventions character demands its interpretation is done without recourse to

national laws); Hofmann, supra note 20, at 146 (attributing harmonization of

European sales law due to CISGs application in most countries).

Вам также может понравиться

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaОт EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (4)

- Stamping Out Uncertainty - The Legal Fiasco of Unstamped Arbitration Agreements in IndiaДокумент7 страницStamping Out Uncertainty - The Legal Fiasco of Unstamped Arbitration Agreements in IndiaAmey KalamkarОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 20Документ20 страницSupreme Court of India Page 1 of 20Nisheeth PandeyОценок пока нет

- Arbitration and Party Autonomy: OKUMA KazutakeДокумент31 страницаArbitration and Party Autonomy: OKUMA KazutakeGraziella AndayaОценок пока нет

- Columbia SP 23 Vol 2 Weeks 5-8Документ735 страницColumbia SP 23 Vol 2 Weeks 5-8Max DiegoОценок пока нет

- Parties' Autonomy in International Commercial ArbitrationДокумент13 страницParties' Autonomy in International Commercial Arbitrationsilvan jasperОценок пока нет

- Name: Hope Brendah: QN: What Are My Major Suggestions For The Amendment of Chinese Arbitration Law (1994) ?Документ12 страницName: Hope Brendah: QN: What Are My Major Suggestions For The Amendment of Chinese Arbitration Law (1994) ?Hope BrendaОценок пока нет

- Model Law PDFДокумент8 страницModel Law PDFRap PatajoОценок пока нет

- Adr Unicitral OutlineДокумент17 страницAdr Unicitral OutlineKat MirandaОценок пока нет

- Limits To Party Autonomy in International Commercial ArbitrationДокумент13 страницLimits To Party Autonomy in International Commercial ArbitrationdiannageneОценок пока нет

- ICA SynopsisДокумент4 страницыICA SynopsisArpit GoyalОценок пока нет

- Court Intervention in International ArbitrationДокумент34 страницыCourt Intervention in International ArbitrationyaerhОценок пока нет

- Comparative Outlook of The Enforcement of Uncitral Model Law in India and UkДокумент18 страницComparative Outlook of The Enforcement of Uncitral Model Law in India and UkAnirudh KaushalОценок пока нет

- A Guide To Procedural Issues in International ArbitrationДокумент13 страницA Guide To Procedural Issues in International Arbitrationabuzar ranaОценок пока нет

- ADR-Group 7-Section 10 of The Arbitration Act To Arbitration in KenyaДокумент11 страницADR-Group 7-Section 10 of The Arbitration Act To Arbitration in KenyaNafula CОценок пока нет

- Procedures in International Commercial ArbitrationДокумент12 страницProcedures in International Commercial Arbitrationshaurya raiОценок пока нет

- ADR United Nations Convention On The Recognition and Enforcement by Atty. Joanne Marie ComaДокумент40 страницADR United Nations Convention On The Recognition and Enforcement by Atty. Joanne Marie ComaKristine Hipolito SerranoОценок пока нет

- The Applicable Law in An International Commercial Arbitration: Is It Still A Conflict of Laws Problem?Документ34 страницыThe Applicable Law in An International Commercial Arbitration: Is It Still A Conflict of Laws Problem?Anonymous 94TBTBRksОценок пока нет

- Article 11 and The Model Law Writing RequirementДокумент13 страницArticle 11 and The Model Law Writing RequirementAurica IftimeОценок пока нет

- Philippines - Multi-Tiered Dispute ResolutionДокумент5 страницPhilippines - Multi-Tiered Dispute ResolutionCamille AngelicaОценок пока нет

- Drafting The Icc Arbitral ClauseДокумент29 страницDrafting The Icc Arbitral ClausevishalbalechaОценок пока нет

- Conflict of Law For ArbitratorsДокумент17 страницConflict of Law For ArbitratorsJovana Poppy GolubovićОценок пока нет

- The Role of National Courts in ArbitrationДокумент18 страницThe Role of National Courts in ArbitrationOurvasheeIshnooОценок пока нет

- C O L A: A R O R J T I I: Onundrum F EX Rbitri Eview F Ecent Udicial Rends N NdiaДокумент16 страницC O L A: A R O R J T I I: Onundrum F EX Rbitri Eview F Ecent Udicial Rends N NdiaBhawna NandaОценок пока нет

- Monty D. Denhardt v. Trailways, Inc., 767 F.2d 687, 10th Cir. (1985)Документ4 страницыMonty D. Denhardt v. Trailways, Inc., 767 F.2d 687, 10th Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- IJAL Volume 5 - Issue 1 - M.P. Bharucha Et AlДокумент29 страницIJAL Volume 5 - Issue 1 - M.P. Bharucha Et AlAnonymous IBy6w6mNОценок пока нет

- Conflict of Law - Proper Law of ContractДокумент31 страницаConflict of Law - Proper Law of ContractRachit Munjal100% (1)

- Cordero Moss 2017 Limits To Party Autonomy in International Commercial ArbitrationДокумент20 страницCordero Moss 2017 Limits To Party Autonomy in International Commercial ArbitrationVAISHNAVI RASTOGI 19113047Оценок пока нет

- Arbitrartion Award PDFДокумент13 страницArbitrartion Award PDFRasmirah BeaumОценок пока нет

- Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth Inc - Internat PDFДокумент24 страницыMitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth Inc - Internat PDFHelp MeОценок пока нет

- Indian Private International Law Vis A Vis Party Autonomy in The ChoiceДокумент16 страницIndian Private International Law Vis A Vis Party Autonomy in The Choicepittish 12Оценок пока нет

- Lex Arbitri: Submitted ToДокумент12 страницLex Arbitri: Submitted ToLEX-57 the lex engine100% (1)

- Born - CH 2 - Intl Arbitration AgreementsДокумент21 страницаBorn - CH 2 - Intl Arbitration AgreementsFrancoОценок пока нет

- 12 - Chapter 5Документ72 страницы12 - Chapter 5VishakaRajОценок пока нет

- Public International Law NotesДокумент41 страницаPublic International Law NotesEvelyn Bergantinos DM100% (2)

- HIM Portland, LLC. v. DeVito Builders, Inc, 317 F.3d 41, 1st Cir. (2003)Документ5 страницHIM Portland, LLC. v. DeVito Builders, Inc, 317 F.3d 41, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Jurisdiction of The ICJ, HAGUEДокумент17 страницJurisdiction of The ICJ, HAGUECharity Lasi Magtibay100% (1)

- National Law University, Jodhpur: (CA Towards The Fulfillment of The Assessment in The Subject of ADR)Документ7 страницNational Law University, Jodhpur: (CA Towards The Fulfillment of The Assessment in The Subject of ADR)Aniket SrivastavaОценок пока нет

- International Arbitration Q1Документ3 страницыInternational Arbitration Q1Satya Vrat PandeyОценок пока нет

- Arbitration AgreementsДокумент20 страницArbitration Agreementsmohd suhail siddiqui100% (2)

- Contract Draft 2Документ24 страницыContract Draft 2nishit gokhruОценок пока нет

- Jurisdiction in ArbitrationДокумент35 страницJurisdiction in ArbitrationGheaОценок пока нет

- Komal AdrДокумент12 страницKomal Adrkomalhotchandani1609Оценок пока нет

- Arbitration Law Case CommentaryДокумент9 страницArbitration Law Case CommentaryKoustav BhattacharyaОценок пока нет

- INDTEL CaseДокумент4 страницыINDTEL CaseManisha SinghОценок пока нет

- The Hague Convention of 30 June 2005 On Choice of Court Agreements Outline of The Convention The Purpose of The ConventionДокумент1 страницаThe Hague Convention of 30 June 2005 On Choice of Court Agreements Outline of The Convention The Purpose of The Conventionlito77Оценок пока нет

- Arbitration AgreementДокумент12 страницArbitration AgreementPRABHAT SINGHОценок пока нет

- Recomendada - MOSES, Margaret, The Arbitration Agreement, Pp. 18-34Документ25 страницRecomendada - MOSES, Margaret, The Arbitration Agreement, Pp. 18-34JOSE LUIS ESPINOZA MESTANZAОценок пока нет

- IBA - The Law Governing The Arbitration Agreement (& Assignment)Документ6 страницIBA - The Law Governing The Arbitration Agreement (& Assignment)HeeYoonParkОценок пока нет

- Drafting The International Arbitration Clause Part 1 of 4Документ3 страницыDrafting The International Arbitration Clause Part 1 of 4Mohamed EltaiebОценок пока нет

- 1900-Article Text-3610-1-10-20190327Документ18 страниц1900-Article Text-3610-1-10-20190327Ami TandonОценок пока нет

- Ojps 2016040117235897Документ10 страницOjps 2016040117235897Shurbhi YadavОценок пока нет

- The Concept of "Denationalization" (Or The Equivalent "Delocalization")Документ10 страницThe Concept of "Denationalization" (Or The Equivalent "Delocalization")Shoaib ZaheerОценок пока нет

- Choice of Law RulesДокумент7 страницChoice of Law RuleshaloXDОценок пока нет

- Role of Courts in ArbitrationДокумент23 страницыRole of Courts in ArbitrationAkanksha Singh0% (1)

- Lynchburg Foundry Company v. Patternmakers League of North America and Patternmakers League of North America, Lynchburg Division, 597 F.2d 384, 4th Cir. (1979)Документ6 страницLynchburg Foundry Company v. Patternmakers League of North America and Patternmakers League of North America, Lynchburg Division, 597 F.2d 384, 4th Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- PC Markanda - Arbitration Step by Step - Shristi Roongta PDFДокумент401 страницаPC Markanda - Arbitration Step by Step - Shristi Roongta PDFVijay Singh100% (1)

- IntroductionДокумент5 страницIntroductionSankalp RajОценок пока нет

- Porter Hayden Company v. Century Indemnity Company, 136 F.3d 380, 4th Cir. (1998)Документ6 страницPorter Hayden Company v. Century Indemnity Company, 136 F.3d 380, 4th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Gregorio v. Vda. de CuligДокумент2 страницыGregorio v. Vda. de CuligNatsu DragneelОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law Brief Project, Joshua NazarioДокумент8 страницConstitutional Law Brief Project, Joshua NazarioSean NazОценок пока нет

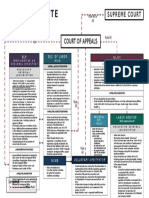

- Labor Dispute Case Flow: Supreme CourtДокумент1 страницаLabor Dispute Case Flow: Supreme Courtjeffprox69100% (1)

- Permanent Savings and Loan Bank v. VelardeДокумент3 страницыPermanent Savings and Loan Bank v. VelardeYodh Jamin OngОценок пока нет

- Response To Response PDFДокумент6 страницResponse To Response PDFNBC MontanaОценок пока нет

- Bernabe Vs Alejo: 374 Scra 180 No Retroactive Effect If Vested Rights Are ImpairedДокумент2 страницыBernabe Vs Alejo: 374 Scra 180 No Retroactive Effect If Vested Rights Are ImpairedAnonymous 96BXHnSziОценок пока нет

- HC Delhi Orders CIC To Maintain Daily Oder Sheets of Each Hearing & Upload Them On Its Website After 3 Days.Документ3 страницыHC Delhi Orders CIC To Maintain Daily Oder Sheets of Each Hearing & Upload Them On Its Website After 3 Days.JAGDISH GIANCHANDANIОценок пока нет

- Senarillos v. Hermosisima, G.R. No. L-10662, 14 December 1956Документ2 страницыSenarillos v. Hermosisima, G.R. No. L-10662, 14 December 1956Cris Angelo AndradeОценок пока нет

- 9 Holdsworth L Rev 59Документ17 страниц9 Holdsworth L Rev 59Srijeeta ChakrabortyОценок пока нет

- Petitioners Vs Vs Respondent George Erwin M. Garcia Nicolas P. Lapena, JRДокумент9 страницPetitioners Vs Vs Respondent George Erwin M. Garcia Nicolas P. Lapena, JRCJ N PiОценок пока нет

- Ra 2260Документ10 страницRa 2260sufistudentОценок пока нет

- Injunction Before The RTC Makati Against Respondent Public Estates Authority (PEA), AДокумент3 страницыInjunction Before The RTC Makati Against Respondent Public Estates Authority (PEA), ASand FajutagОценок пока нет

- Case No.61 of 2013 Surender Prashad Vs Maharastra Power Generation Company LTD Appeal No. 43 of 2014 Shri Surendra Prasad vs. CCIДокумент3 страницыCase No.61 of 2013 Surender Prashad Vs Maharastra Power Generation Company LTD Appeal No. 43 of 2014 Shri Surendra Prasad vs. CCIVijay KandpalОценок пока нет

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents: Second DivisionДокумент8 страницPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents: Second DivisionVener MargalloОценок пока нет

- I-1. G.R. No. L-25920 - CCC Insurance Corp. v. Court of AppealsДокумент5 страницI-1. G.R. No. L-25920 - CCC Insurance Corp. v. Court of AppealsMA. CECILIA F FUNELASОценок пока нет

- Regal Films, Inc. vs. Concepcion: 504 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedДокумент5 страницRegal Films, Inc. vs. Concepcion: 504 Supreme Court Reports Annotatedmilly angОценок пока нет

- Corporation Law - Thomson v. CAДокумент9 страницCorporation Law - Thomson v. CANikko ParОценок пока нет

- Perla Compania de Seguros, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsДокумент9 страницPerla Compania de Seguros, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsJamesОценок пока нет

- 8.) Francisco Motors Corporation vs. Court of Appeals and Spouses Gregorio and Librada ManuelДокумент2 страницы8.) Francisco Motors Corporation vs. Court of Appeals and Spouses Gregorio and Librada ManuelPerla VirayОценок пока нет

- Arun Mishra and M.R. Shah, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2019 (II) OLR714Документ2 страницыArun Mishra and M.R. Shah, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2019 (II) OLR714Octogenarian GruntОценок пока нет

- Central Azucarera de Bais v. Heirs of Apostol, G.R. No. 215314, (March 14, 2018)Документ10 страницCentral Azucarera de Bais v. Heirs of Apostol, G.R. No. 215314, (March 14, 2018)RJCenitaОценок пока нет

- Knapp v. MSPB 2020-2122Документ6 страницKnapp v. MSPB 2020-2122FedSmith Inc.Оценок пока нет

- Council V Nash PDFДокумент3 страницыCouncil V Nash PDFRichardОценок пока нет

- Ong vs. Republic (Case Digest) : July 1, 1999 - Petitioner Charles Ong, in Behalf of His Brothers, Filed For AnДокумент5 страницOng vs. Republic (Case Digest) : July 1, 1999 - Petitioner Charles Ong, in Behalf of His Brothers, Filed For AnKris tyОценок пока нет

- CIR v. PNBДокумент3 страницыCIR v. PNBAngelique Padilla UgayОценок пока нет

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitДокумент1 страницаUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Victory Liner, Inc. Vs Michael MaliniasДокумент8 страницVictory Liner, Inc. Vs Michael MaliniasJeremiah TrinidadОценок пока нет

- Civil Servants Efficiency and Descipline Rules in FGEI Qammer ShahzadДокумент38 страницCivil Servants Efficiency and Descipline Rules in FGEI Qammer ShahzadQammer ShahzadОценок пока нет

- Republic Vs CA 107 SCRA 504Документ2 страницыRepublic Vs CA 107 SCRA 504Neon True BeldiaОценок пока нет

- Vijay Prakash Singh Vs Union of India Others On 27 July 2018Документ4 страницыVijay Prakash Singh Vs Union of India Others On 27 July 2018Prateek RaiОценок пока нет