Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

CivPro Reviewer

Загружено:

Courtney PaduaИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CivPro Reviewer

Загружено:

Courtney PaduaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

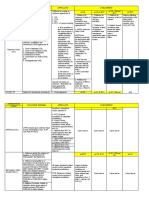

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

Based on Justice De Leons Outline, Civil Procedure by

Riano, San Beda Reviewer, and 1997 Rules of Court

Digests (by Abdulwahid, Cabal, Comafay, Fuster, Leynes,

Mendame, Mendez, Paras & Regis) further summarized.

BASIC PRINCIPLES

Difference between substantive and remedial law

SUBSTANTIVE LAW

It creates, defines and

regulates rights and

duties concerning life,

liberty or property,

which when violated

gives rise to a cause of

action.

Civil actions,

proceedings

criminal

REMEDIAL LAW

It

prescribes

the

methods of enforcing

those

rights

and

obligations created by

substantive law by

providing a procedural

system for obtaining

redress for the invasion

of rights and violations

of duties and by

prescribing rules as to

how suits are filed, tried

and decided upon by

the courts.

actions,

and

special

(1) Civil actions

It is one by which a party sues another for the

protection of a right or the prevention or

redress of a wrong. Its primary purpose is

compensatory. Civil actions may be:

(a) Ordinary, or

(b) Special.

Both are governed by rules for

ordinary civil actions, subject to specific rules

prescribed for special civil actions.

(2) Criminal actions

It is one by which the State prosecutes a

person for an act or omission punishable by

law. Its primary purpose is punishment.

(3) Special proceedings

It is a remedy by which a party seeks to

establish a status, a right or a particular fact.

Three (3) limitations on the SCs rule-making power:

(1) The rules shall provide a simplified and

inexpensive procedure for the speedy

disposition of cases;

(2) shall be uniform for courts of the same grade;

and

(3) shall not diminish, increase, or modify

substantive rights.

Article 6, Sec. 30, Constitution

No law shall be passed increasing the appellate

jurisdiction of the Supreme Court as provided in this

Constitution without its advice and concurrence.

Procedural and substantive rules

Substantive law creates, defines, regulates, and

extinguishes rights and obligations, while remedial or

procedural law provides the procedure for the

enforcement of rights and obligations.

Force and effect of Rules of Court

The Rules of Court have the force and effect of law,

unless they happen to be inconsistent with positive law.

Power of Supreme Court to suspend the Rules of

Court

Whenever demanded by justice, the Supreme Court has

the inherent power to

(a) suspend its own rules or

(b) exempt a particular case from the operation of

said rules.

May parties change the rules of procedure?

General rule: They may not. This is because these are

matters of public interest.

Exceptions:

Matters of procedure which may be

Agreed upon by the parties Venue may be

changed by written agreement of the parties

(Rule 4, Sec. 4[b])

Waived Venue may be waived if not

objected to in a motion to dismiss or in the

answer. (Rule 16, Sec. 6); judgment in default

may be waived by failure to answer within 15

days.

Fall within the discretion of the court The

period to plead may be extended on motion of

a party. (Rule 11, Sec. 11); rules of procedure

may be relaxed in the interest of justice.

GENERAL PROVISIONS (Rule 1)

JURISDICTION

It is the power and authority of a court to hear, try and

decided a case.

Rule-making power of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court has the constitutional power to

promulgate rules concerning:

(1) Pleading,

(2) Practice, and

(3) Procedure.

1. Generally

The statute in force at the time of the

commencement of the action determines the

jurisdiction of the court.

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

Before looking into other matters, it is the

duty of the court to consider the question of

jurisdiction without waiting for it to be raised.

If court has jurisdiction, such must

be exercised. Otherwise, it may be

enforced by a mandamus proceeding.

If court has no jurisdiction, the court

shall dismiss the claim and can do so

motu proprio.

Doctrine of primary jurisdiction

The courts will not resolve a controversy

involving a question which is within the

jurisdiction of an administrative tribunal.

Doctrine of continuing jurisdiction

Once jurisdiction has attached to a court, it

retains that jurisdiction until it finally

disposes of the case. Hence, it is not lost by

The

passage

of

new

laws

transferring the jurisdiction to

another tribunal except when

expressly provided by the statute;

Subsequent filing of a notice of

appeal;

The mere fact that a party who is a

public official ceased to be in office;

or

Finality of judgment (the court still

has jurisdiction to enforce and

execute it)

Elements of a valid exercise of jurisdiction

(1) Jurisdiction over the subject matter or nature

of the case;

(2) the parties;

(3) the res if jurisdiction over the defendant

cannot be acquired;

(4) the issue of the case; and

(5) Payment of docket fees.

Jurisdiction over the subject matter is a matter of

substantive law.

Jurisdiction over the parties, the res and the

issues are matters of procedure. Jurisdiction over the

parties and the res are covered by the rule on summons,

while jurisdiction over the issues is subsumed under

the rule on pleadings.

(a) As to subject matter

Jurisdiction over the subject matter is conferred by the

Constitution or by law.

Therefore, jurisdiction over the subject matter

cannot be conferred by

(1) Administrative policy of any court;

(2) Courts unilateral assumption of jurisdiction;

(3) Erroneous belief by the court that it has

jurisdiction;

(4) By contract or by the parties;

(5) By agreement, or by any act or omission of the

parties, nor by acquiescence of the court; or

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

(6) By the parties silence, acquiescence or

consent

General Rule: It is determined by the material

allegations of the initiatory pleading (e.g., the

complaint), not the answer of the defendant. Once

acquired, jurisdiction is not lost because of the

defendants contrary allegation.

Exception: In ejectment cases, where tenancy is

averred by way of defense and is proved to be the

real issue, the case should be dismissed for not

being properly filed with the DARAB.

It is determined by the cause of action alleged, not

by the amount substantiated and awarded.

Example: If a complaint alleges a recoverable

amount of P1M, RTC has jurisdiction even if

evidence proves the only P300k may be recovered.

Note: Jurisdiction over the subject matter CANNOT be

waived, enlarged or diminished by stipulation of the

parties.

(b) As to res or property

Jurisdiction over the res refers to the courts

jurisdiction over the thing or the property which is the

subject of the action.

Jurisdiction over the res is acquired by

(1) Custodia legisplacing the property or thing

under the courts custody (e.g., attachment)

(2) Statutory authoritystatute conferring the

court with power to deal with the property or

thing within its territorial jurisdiction

(3) Summons by publication or other modes of

extraterritorial service (Rule 14, Sec. 15)

(c) As to the issues

Issue a disputed point or question to which parties to

an action have narrowed down their several allegations

and upon which they are desirous of obtaining a

decision. Thus, where there is no disputed point, there

is no issue.

Jurisdiction over the issue may be conferred or

determined by

(1) Examination of the pleadings

Generally, jurisdiction over the issues is

determined by the pleadings of the parties.

(2) Pre-trial

It may be conferred by stipulation of the

parties in the pre-trial, as when they enter

into stipulations of facts and documents or

enter into an agreement simplifying the issues

of the case (Rule 18, Sec. 2)

(3) Waiver

Failure to object to presentation of evidence

on a matter not raised in the pleadings. Said

issues tried shall be treated as if they had

been raised in the pleadings.

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

(d) As to the parties

The court acquires jurisdiction over the

Plaintiff

when he files his complaint

Defendant

i.

Valid service of summons upon him, or

ii.

Voluntary appearance:

The defendants voluntary appearance in

the action shall be equivalent to service of

summons. The inclusion in a motion to

dismiss of other grounds aside from lack

of jurisdiction over the person of the

defendant shall not be deemed a

voluntary appearance. (Rule 14, Sec. 20)

Examples:

When defendant files

The necessary pleading;

A motion for reconsideration;

Petition to set aside judgment o f

default;

An answer;

Petition for certiorari without

questioning the courts jurisdiction

over his person; or

When the parties jointly submit a

compromise agreement for approval

BUT the filing of an answer should not be

treated automatically as a voluntary

appearance when such answer is

precisely to object to the courts

jurisdiction over the defendants person.

La Naval v. CA: A defendant should be

allowed to put up his own defenses

alternatively or hypothetically. It should

not be the invocation of available

additional defenses that should be

construed as a waiver of the defense of

lack of jurisdiction over the person, but

the failure to raise the defense.

Note: Jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant

cannot be acquired if the action is in personam.

2. Estoppel to deny jurisdiction

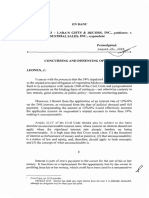

HEIRS OF BERTULDO HINOG v. MELICOR

(455 SCRA 460, 2005)

Since the deceased defendant participated in all

stages of the case before the trial court, he is

estopped from denying the jurisdiction of the court.

The petitioners merely stepped into the shoes of

their predecessor and are effectively barred by

estoppel from challenging RTCs jurisdiction.

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

FACTS: Bertuldo Hinog allegedly occupied and built a

small house on a portion of a property owned by

respondents Balane for 10 years at a nominal annual

rental. After 10 years, Bertuldo refused to heed

demands made by respondents to return said portion

and to remove the house constructed thereon.

Respondents filed a complaint against him. Bertuldo

filed his Answer, alleging ownership of the disputed

property by virtue of a Deed of Absolute Sale. Bertuldo

died without completing his evidence during the direct

examination. Bertuldos original counsel was replaced

by Atty. Petalcorin who entered his appearance as new

counsel for the heirs of Bertuldo.

Atty. Petalcorin filed a motion to expunge the

complaint from the record and nullify all court

proceedings on the ground that private respondents

failed to specify in the complaint the amount of

damages claimed so as to pay the correct docket fees;

and that under Manchester doctrine, non-payment of

the correct docket fee is jurisdictional.

ISSUE: Whether the petitioners are barred by estoppel

from questioning the jurisdiction of RTC

YES. The petitioners are barred from

questioning jurisdiction of the trial court. Although the

issue of jurisdiction at any stage of the proceedings as

the same is conferred by law, it is nonetheless settled

that a party may be barred from raising it on the

ground of estoppel. After the deceased Bertuldo

participated in all stages of the case before the trial

court, the petitioners merely stepped into the shoes of

their predecessor and are effectively barred by estoppel

from challenging RTCs jurisdiction.

3. Jurisdiction at the time of filing of action

PEOPLE v. CAWALING

(293 SCRA 267, 1998)

The jurisdiction of a court to try a criminal case is

determined by the law in force at the time of the

institution of the action. Once the court acquires

jurisdiction, it may not be ousted from the case by

any subsequent events, such as a new legislation

placing such proceedings under the jurisdiction of

another tribunal. Exceptions to this rule arise when:

(1) there is an express provision in the statute, or

(2) the statute is clearly intended to apply to actions

pending before its enactment.

FACTS: Brothers Vicente and Ronie Elisan were

drinking tuba at the kitchenette of one of the accused,

Fontamilla. When they were about to leave, they were

warned by Luz Venus that the six (6) accused consisting

of Mayor Cawaling, four (4) policemen and a civilian,

had been watching and waiting for them outside the

restaurant. Nevertheless, the two went out and were

chased by the armed men. Vicente successfully ran and

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

hid behind a coconut tree while Ronie unfortunately

went to the ricefield and was shot to death there.

An Information alleging murder was filed in

the RTC against the 6 accused. RTC convicted them of

murder. On appeal, the appellants questioned the

jurisdiction of the RTC over the case, insisting that the

Sandiganbayan was the tribunal with jurisdiction since

the accused were public officers at the time of the

killing.

ISSUE: Whether the Sandiganbayan had jurisdiction

NO. The jurisdiction of a court to try a

criminal case is determined by the law in force at the

time of the institution of the action. Once the court

acquires jurisdiction, it may not be ousted from the case

by any subsequent events, such as a new legislation

placing such proceedings under the jurisdiction of

another tribunal. Exceptions to this rule arise when:

(1) there is an express provision in the statute, or (2)

the statute is clearly intended to apply to actions

pending before its enactment.

Section 4-a-2 of PD 1606, as amended by PD

1861 lists two requisites that must concur before the

Sandiganbayan may exercise exclusive and original

jurisdiction over a case: (a) the offense was committed

by the accused public officer in relation to his office;

and (b) the penalty prescribed by law is higher than

prision correccional or imprisonment for six (6) years,

or higher than a fine of P6,000.

Sanchez vs. Demetriou clarified that murder or

homicide may be committed both by public officers and

by private citizens, and that public office is not a

constitutive element of said crime. The relation

between the crime and the office contemplated should

be direct and not accidental.

The Information filed against the appellants

contains no allegation that appellants were public

officers who committed the crime in relation to their

office. The charge was only for murder.

In the absence of any allegation that the

offense was committed in relation to the office of

appellants or was necessarily connected with the

discharge of their functions, the regional trial court, not

the Sandiganbayan, has jurisdiction to hear and decide

the case.

REGULAR COURTS (MTC, RTC, CA, SC)

(See San Beda Reviewer)

SPECIAL COURTS (Sandiganbayan)

(See San Beda Reviewer)

QUASI-JUDICIAL BODIES

Securities and Exchange Commission (Sec. 5.2, RA

8799)

The Commission shall retain jurisdiction over

Pending cases involving intra-corporate

disputes submitted for final resolution which

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

should be resolved within one (1) year from

the enactment of this Code, and

Jurisdiction over pending suspension of

payments/rehabilitation cases filed as of 30

June 2000 until finally disposed.

Civil Service Commission

MAGPALE v. CSC (215 SCRA 398, 1992)

Under Section 47 of the Administrative Code, the

CSC shall decide on appeal all administrative

disciplinary cases involving the imposition of (d)

removal or dismissal from office.

The MPSB decision did not involve

dismissal or separation from office, rather, the

decision exonerated petitioner and ordered him

reinstated to his former position. The MSPB

decision was not a proper subject of appeal to the

CSC.

FACTS: Magpale, port manager of Philippine Ports

Authority-Port Management Unit (PPA-PMU) of

Tacloban, was found by the Secretary of DOTC guilty of

Gross Negligence on two counts: (a) for his failure to

account for the 44 units of equipment and (b) for failing

to render the required liquidation of his cash advances

amounting to P44,877.00 for a period of 4 yrs. He was

also found guilty of frequent and unauthorized

absences. He was meted the penalty of dismissal from

the service with the corresponding accessory penalties.

He appealed to the Merit System and

Protection Board (MSPB) of the Civil Service

Commission (CSC). The MSPB reversed the decision.

PPA filed an appeal with the Civil Service Field

Office-PPA, which indorsed the appeal to CSC. Magpale

moved for the implementation of the MSPB decision

which was opposed by the PPA. MSPB ordered the

immediate implementation of its decision, which

became final and executory.

Respondent CSC reversed MPSBs decision

and held Magpale guilty.

ISSUE: Whether the law authorized an appeal by the

government from an adverse decision of the MSBP

NO. Under the Administrative Code of 1987,

decisions of the MPSB shall be final, except only those

involving dismissal or separation from the service

which may be appealed to the Commission

While it is true that the CSC does have the

power to hear and decide administrative cases

instituted by or brought before it directly or on appeal,

the exercise of the power is qualified by and should be

read together with Sec. 49 of Executive Order 292,

which prescribes, among others that (a) the decision

must be appealable.

Under Section 47 of the Administrative Code,

the CSC shall decide on appeal all administrative

disciplinary cases involving the imposition of:

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

(a) a penalty of suspension for more than 30

days;

(b) fine in an amount exceeding 30 days salary;

(c) demotion in rank or salary or transfer; or

(d) removal or dismissal from office.

The MPSB decision did not involve dismissal or

separation from office, rather, the decision exonerated

petitioner and ordered him reinstated to his former

position. The MSPB decision was not a proper subject of

appeal to the CSC.

Settled is the rule that a tribunal, board, or

officer exercising judicial functions acts without

jurisdiction if no authority has been conferred by law to

hear and decide the case.

Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB)

SANDOVAL v. CAEBA

(190 SCRA 77, 1991)

It is not the ordinary courts but the National

Housing Authority (NHA) which has exclusive

jurisdiction to hear and decide cases of (a)

unsound real estate business practices; (b) claims

involving refund and any other claims filed by

subdivision lot or condominium unit buyer against

the project owner, developer, dealer, broker or

salesman; and (c) cases involving specific

performance of contractual and statutory

obligations filed by buyers of subdivision lot or

condominium unit against the owner, developer,

dealer, broker or salesman.

FACTS: Estate Developers and Investors Corporation

(Estate) filed a complaint against Nestor Sandoval

(Sandoval) in the RTC for the collection of unpaid

installments of a subdivision lot, pursuant to a

promissory note, plus interest. Sandoval alleges that he

suspended payments thereof because of the failure of

the developer to develop the subdivision pursuant to

their agreement. The RTC ruled in favor of Estate, and

ordered Sandoval to pay. A writ of execution was issued

which thereafter became final and executory.

Sandoval filed a motion to vacate judgment

and to dismiss the complaint on the ground that the

RTC had no jurisdiction over the subject matter. A

motion for reconsideration of the writ of execution was

also filed by petitioner. Estate opposed both motions.

RTC denied the motion to vacate for the reason that it is

now beyond the jurisdiction of the court to do so. A new

writ of execution was issued.

Sandoval filed a petition alleging that the RTC

committed grave abuse of discretion since the exclusive

and original jurisdiction over the subject-matter thereof

is vested with the Housing and Land Use Regulatory

Board (HLURB) pursuant to PD 957.

ISSUE: Whether the ordinary courts have jurisdiction

over the collection of unpaid installments regarding a

subdivision lot

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

NO. Under Section 1 of Presidential Decree

No. 957 the National Housing Authority (NHA) was

given the exclusive jurisdiction to hear and decide

certain cases of the following nature:

(a) Unsound real estate business practices:

(b) Claims involving refund and any other claims

filed by subdivision lot or condominium unit

buyer against the project owner, developer,

dealer, broker or salesman; and

(c) Cases involving specific performance of

contractual and statutory obligations filed by

buyers of subdivision lot or condominium unit

against the owner, developer, dealer, broker

or salesman.

The exclusive jurisdiction over the case between the

petitioner and private respondent is vested not on the

RTC but on the NHA. The NHA was re-named Human

Settlements Regulatory Commission and thereafter it

was re-named as the Housing and Land Use Regulatory

Board (HLURB).

KINDS OF ACTION

1. As to cause or foundation

The distinction between a real action and a personal

action is important for the purpose of determining the

venue of the action.

(a) Personal

Personal actions are those other than real actions. (Sec.

2, Rule 4)

Examples

Action for specific performance

Action for damages to real property

Action for declaration of the nullity of

marriage

Action to compel mortgagee to accept

payment of the mortgage debt and release the

mortgage

(b) Real

An action is real when it affects title to or possession of

real property, or an interest therein. (Sec. 1, Rule 4)

To be a real action, it is not enough that it

deals with real property. It is important that the matter

in litigation must also involve any of the following

issues:

(a) Title;

(b) Ownership;

(c) Possession;

(d) Partition;

(e) Foreclosure of mortgage; or

(f) Any interest in real property

Examples

Action to recover possession of real property

plus damages (damages is merely incidental)

Action to annul or rescind a sale of real

property

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

2. As to object

The distinctions are important

(a) to determine whether the jurisdiction of the

defendant is required, and

(b) to determine the type of summons to be

employed

(a) In rem

An action is in rem when it is directed against the whole

world. It is for the determination of the state or

condition of a thing.

Examples

Probate proceeding

Cadastral proceeding

(b) In personam

A proceeding in personam is a proceeding to enforce

personal rights and obligations brought against the

person and is based on the jurisdiction of the person.

Its purpose is to impose some responsibility

or liability directly upon the person of the defendant. In

an action in personam, no one other than the defendant

is sought to be held liable.

Examples

Action for sum of money

Action for damages

(c) Quasi in rem

An action quasi in rem is one wherein an individual is

named as defendant and the purpose of the proceeding

is to subject his interest therein to the obligation or lien

burdening the property.

Such action deals with the status, ownership

or liability of a particular property, but which are

intended to operate on these questions only as between

the particular parties to the proceedings, and not to

ascertain or cut-off the rights or interests of all possible

claimants.

NOTE: These rules are inapplicable in the following

cases:

(1) Election cases;

(2) Land registration;

(3) Cadastral;

(4) Naturalization;

(5) Insolvency proceedings;

(6) Other cases not herein provided for, except by

analogy or in a suppletory character, and

whenever practicable and convenient.

(Sec. 4, Rule 1)

COMMENCEMENT OF ACTION (Sec. 5, Rule 1)

A civil action is commenced

by the filing of the original complaint in court,

or

on the date of the filing of the later pleading if

an additional defendant is impleaded

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

irrespective of whether the motion for its

admission, if necessary, is denied by the court.

(with respect only to the defendant later

impleaded)

1. Condition precedent

matters which must be complied with before a cause

of action arises.

When a claim is subject to a condition

precedent, compliance must be alleged in the

pleading.

Failure to comply with a condition precedent

is an independent ground for a motion to

dismiss. (Sec. 1 [j], Rule 16)

Examples:

Tender of payment before consignation

Exhaustion of administrative remedies

Prior resort to barangay conciliation

proceedings

Earnest efforts towards a compromise

Arbitration proceedings, when contract so

provides

Katarungang Pambarangay (RA 7160)

Purpose: To reduce the number of court litigations and

prevent the deterioration of the quality of justice which

has been brought by the indiscriminate filing of cases in

the courts.

Only individuals shall be parties to KB

proceedings, no juridical entities.

Parties must personally appear in all KB

proceedings and without assistance of counsel

or representatives, except for minors and

incompetents who may be assisted by their

next-of-kin, not lawyers.

Conciliation proceedings required is not a

jurisdictional requirement.

NOTE: Failure to undergo the barangay

conciliation proceedings is non-compliance of

a condition precedent. Hence, a motion to

dismiss a civil complaint may be filed. (Sec. 1

[j], Rule 16).

BUT the court may not motu proprio dismiss

the case for failure to undergo conciliation.

Initiation of proceedings

(1) Payment of appropriate filing fee

(2) Oral or written complaint to the Punong

Barangay (chairman of the Lupon)

(3) Chairman shall summon respondents to

appear the next working day

(4) Mediation proceedings for 15 days

(5) Should the chairman fail in his mediation

efforts within said period, he shall constitute

the Pangkat Tagapagkasundo,

(6) If no amicable settlement is reached, the

chairman shall issue a certification to file

action.

All amicable settlements shall be

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

In writing;

In a language or dialect known to the parties;

Signed by them; and

Attested to by the lupon chairman or the

pangkat chairman, as the case may be.

Effect

The amiable settlement and arbitration award shall

have the effect of a final judgment of a court upon

expiration of 10 days from date thereof, unless:

(1) Repudiation of the settlement has been made,

or

(2) Petition to nullify the award has been filed

before the proper city or municipal ourt

Execution shall issue upon expiration of 10 days from

settlement.

LUMBUAN v. RONQUILLO

(489 SCRA 650, 2006)

While admittedly no pangkat was constituted, the

parties met at the office of the Barangay Chairman

for possible settlement. The act of Lumbuan in

raising the matter to the Katarungang

Pambarangay and the subsequent confrontation of

the lessee and lessor before the Lupon Chairman or

the pangkat is sufficient compliance with the

precondition for filing the case in court.

FACTS: Lumbuan (lessor) leased a lot to respondent

Ronquillo (lessee) for 3 years at a rental of

P5000/month. They agreed that: (a) there will be an

annual 10% increase in rent for the next 2 years; and

(b) the leased premises shall be used only for lessees

fastfood business. Ronquillo failed to abide by the

conditions, and refused to pay or vacate the leased

premises despite Lumbuans repeated verbal demands.

Lumbuan referred the matter to the Barangay

Chairmans Office but no amicable settlement was

reached. The barangay chairman issued a Certificate to

File Action. Lumbuan filed an action for Unlawful

Detainer with MeTC of Manila which ordered

respondent Ronquillo to vacate the leased premises and

to pay P46,000 as unpaid rentals.

RTC set aside the MeTC decision and directed

the parties to go back to the Lupon Chairman or Punong

Barangay for further proceedings and to comply strictly

with the condition that should the parties fail to reach

an amicable settlement, the entire case will be

remanded to the MeTC for it to decide the case anew.

The CA reversed the RTC and ordered the

dismissal of the ejectment case, ruling that when a

complaint is prematurely instituted, as when the

mandatory mediation and conciliation in the barangay

level had not been complied with, the court should

dismiss the case and not just remand the records to the

court of origin so that the parties may go through the

prerequisite proceedings.

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

ISSUE: Whether the CA properly dismissed complaint for

failure of the parties to comply with the mandatory

mediation and conciliation proceedings in the barangay

level

NO. It should be noted that although no

pangkat was formed since no amicable settlement was

reached by the parties before the Katarungang

Pambarangay, there was substantial compliance with

Section 412(a) of R.A. 7160.

While admittedly no pangkat was constituted,

the parties met at the office of the Barangay Chairman

for possible settlement. Thereby, the act of petitioner

Lumbuan in raising the matter to the Katarungang

Pambarangay and the subsequent confrontation of the

lessee and lessor before the Lupon Chairman or the

pangkat is sufficient compliance with the precondition

for filing the case in court. This is true notwithstanding

the mandate of Section 410(b) of the same law that the

Barangay Chairman shall constitute a pangkat if he fails

in his mediation efforts. Section 410(b) should be

construed together with Section 412, as well as the

circumstances obtaining in and peculiar to the case. On

this score, it is significant that the Barangay Chairman

or Punong Barangay is herself the Chairman of the

Lupon under the Local Government Code.

2. Payment of filing fee

Payment of the prescribed docket fee vests a trial court

with jurisdiction over the subject matter or nature of

the action. The court acquires jurisdiction upon

payment of the correct docket fees.

All complaints, petitions, answers, and similar

pleadings must specify the amount of

damages being prayed for, both in the body of

the pleadings and in the assessment of the

filing fees.

Manchester v. CA: Any defect in the original

pleading resulting in underpayment of the

docket fee cannot be cured by amendment,

and for all legal purposes, the court acquired

no jurisdiction in such case.

BUT nonpayment of filing fees does not

automatically cause the dismissal of the case.

The fee may be paid within the applicable

prescriptive or reglementary period.

HEIRS OF BERTULDO HINOG v. MELICOR

(455 SCRA 460, 2005)

Non-payment at the time of filing does not

automatically cause the dismissal of the case, as

long as the fee is paid within the applicable

prescriptive or reglementary period, more so when

the party involved demonstrates a willingness to

abide by the rules prescribing such payment. Thus,

when insufficient filing fees were initially paid by

the plaintiffs and there was no intention to defraud

the government, the Manchester rule does not

apply.

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

FACTS: Respondents filed a complaint against Bertuldo

for recovery of ownership of the premises leased by the

latter. Bertuldo alleged ownership of the property by

virtue of a Deed of Absolute Sale. Bertuldo died without

completing his evidence during the direct examination.

Atty. Petalcorin replaced the original counsel and filed a

motion to expunge the complaint from the record and

nullify all court proceedings on the ground that

private respondents failed to specify in the

complaint the amount of damages claimed as needed

to pay the correct docket fees, and that under

Manchester doctrine, non-payment of the correct

docket fee is jurisdictional.

ISSUE: Whether the nonpayment of the correct docket fee

is jurisdictional in the present case

NO. While the payment of the prescribed

docket fee is a jurisdictional requirement, even its nonpayment at the time of filing does not automatically

cause the dismissal of the case, as long as the fee is paid

within the applicable prescriptive or reglementary

period, more so when the party involved demonstrates

a willingness to abide by the rules prescribing such

payment. Thus, when insufficient filing fees were

initially paid by the plaintiffs and there was no

intention to defraud the government, the Manchester

rule does not apply.

SUN INSURANCE OFFICE v. ASUNCION

(170 SCRA 274, 1989)

Where the filing of the initiatory pleading is not

accompanied by payment of the docket fee, the

court may allow payment of the fee within a

reasonable time but in no case beyond the

applicable prescriptive or reglementary period.

Where the trial court acquires jurisdiction over a

claim by the filing of the pleading and payment of

prescribed filing fees but the judgment awards a

claim not specified in the pleading, or if specified

the same has been left for the courts

determination, the additional filing fee shall

constitute a lien on the judgment. It shall be the

responsibility of the Clerk of Court or his duly

authorized deputy to enforce said lien and assess

and collect the additional fee.

FACTS

Sun Insurance Office, Ltd. (SIOL) filed a complaint

against Uy for the consignation of a premium refund on

a fire insurance policy with a prayer for the judicial

declaration of its nullity. Uy was declared in default for

failure to file the required answer within the

reglementary period. Uy filed a complaint in the RTC for

the refund of premiums and the issuance of a writ of

preliminary attachment initially against petitioner SIOL,

but thereafter included Philipps and Warby as

additional defendants. The complaint sought the

payment of actual, compensatory, moral, exemplary

and liquidated damages, attorney's fees, expenses of

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

litigation and costs of the suit. Although the prayer in

the complaint did not quantify the amount of damages

sought said amount may be inferred from the body of

the complaint to be about P50,000,000.

Uy paid only P210.00 as docket fee, which

prompted petitioners' counsel to raise his objection for

under-assessment of docket fees.

Petitioners allege that while Uy had paid

P182,824.90 as docket fee, and considering that the

total amount sought in the amended and supplemental

complaint is P64,601,623.70, the docket fee that should

be paid by private respondent is P257,810.49, more or

less. Not having paid the same, petitioners contend that

the complaint should be dismissed and all incidents

arising therefrom should be annulled.

ISSUE: Whether or not a court acquires jurisdiction over

case when the correct and proper docket fee has not yet

been paid

YES. Where the filing of the initiatory pleading

is not accompanied by payment of the docket fee, the

court may allow payment of the fee within a reasonable

time but in no case beyond the applicable prescriptive

or reglementary period. Where the trial court acquires

jurisdiction over a claim by the filing of the appropriate

pleading and payment of the prescribed filing fee but,

subsequently, the judgment awards a claim not

specified in the pleading, or if specified the same has

been left for determination by the court, the additional

filing fee therefore shall constitute a lien on the

judgment. It shall be the responsibility of the Clerk of

Court or his duly authorized deputy to enforce said lien

and assess and collect the additional fee.

The same rule applies to permissive

counterclaims, third party claims and similar pleadings,

which shall not be considered filed until and unless the

filing fee prescribed therefore is paid.

CAUSE OF ACTION (RULE 2)

Cause of Action

A cause of action is the act or omission by which a party

violates the rights of another. (Sec. 2, Rule 2)

Every ordinary civil action must be based on a

cause of action. (Sec. 1, Rule 2)

Elements:

(1) A legal right in favor of the plaintiff;

(2) A correlative obligation on the part of the

named defendant to respect or to not violate

such right; and

(3) Act or omission on the part of defendant in

violation of the right of the plaintiff, or

constituting a breach of the obligation of the

defendant to the plaintiff for which the latter

may maintain an action for recovery of

damages or other appropriate relief.

Distinguished from right of action

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

Cause of action is the reason for bringing an action, the

formal statement of operative facts giving rise to a

remedial right, and is governed by procedural law. A

right of action is the remedy for bringing an action and

is solely dependent on substantive law.

Right of action, elements

(1) There must be a good cause;

(2) A compliance with all the conditions

precedent to the bringing of the action; and

(3) The action must be instituted by the proper

party.

Splitting a cause of action

Splitting of cause of action is the act of dividing a single

or indivisible cause of action into several parts or

claims and bringing several actions thereon.

A party may not institute more than one suit

for a single cause of action. (Sec. 3, Rule 2)

If two or more suits are instituted on the basis

of the same cause of action, the filing of one or

a judgment upon the merits in any one is

available as a ground for the dismissal of the

others. (Sec. 4, Rule 2)

Applies also to counterclaims and crossclaims.

Examples

Single cause of action (Cannot be filed separately)

A suit for the recovery of land and a separate

suit to recover the fruits

Action to recover damages to person and

action for damages to same persons car

Action for recovery of taxes and action to

demand

surcharges

resulting

from

delinquency in payment of said taxes

Action to collect debt and to foreclose

mortgage

Action for partition and action for the

recovery

of

compensation

on

the

improvements

Action for annulment of sale and action to

recover dividends

Distinct causes of action (separate filing allowed)

Action for reconveyance of title over property

and action for forcible entry or unlawful

detainer

Action for damages to a car in a vehicular

accident, and another action for damages for

injuries to a passenger other than the owner

of the car

Action to collect loan and action for rescission

of mortgage

Action based on breach of contract of carriage

and action based on quasi-delict

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

JOSEPH v. BAUTISTA

(170 SCRA 540, 1989)

Where there is only one delict or wrong, there is but

a single cause of action regardless of the number of

rights that may have been violated belonging to one

person. Nevertheless, if only one injury resulted

from several wrongful acts, only one cause of action

arises.

FACTS: Joseph, petitioner, boarded Perezs cargo truck

with a load of livestock. At the highway, the truck driver

overtook a tricycle but hit a mango tree when a pick-up

truck tried to overtake him at the same time. This

resulted to the bone fracture of the petitioners leg.

Petitioner filed a complaint for damages

against Perez, as owner, based on a breach of contract

of carriage, and against Sioson and Villanueva, the

owner and driver of the pick-up truck, based on quasidelict. Petitioner impleaded Pagarigan and Vargas,

since he could not ascertain who the real owners of the

pick-up truck and the cargo truck were. Perez filed a

cross-claim against the other respondents for

indemnity, in the event that she is ordered to pay.

The other respondents paid petitioner's claim

for injuries, so they were released from liability. They

also paid Perez for her claim of damages. They

thereafter filed a Motion to Exonerate and Exclude

themselves since theyve already paid Joseph by way of

amicable settlement and Perezs claim for damages.

Perez filed an Opposition to the motion since the

release of claim executed by petitioner in favor of the

other respondents allegedly inured to his benefit. RTC

dismissed the case.

ISSUE: Whether the judgment on the compromise

agreement under the cause of action based on quasidelict is a bar to the cause of action for breach of

contract of carriage

YES. A single act or omission can be violative

of various rights at the same time, as when the act

constitutes a juridical a violation of several separate

and distinct legal obligations. However, where there is

only one delict or wrong, there is but a single cause of

action regardless of the number of rights that may have

been violated belonging to one person. Nevertheless, if

only one injury resulted from several wrongful acts,

only one cause of action arises.

There is no question that petitioner sustained

a single injury on his person, which vested in him a

single cause of action, albeit with the correlative rights

of action against the different respondents through the

appropriate remedies allowed by law. Only one cause of

action was involved although the bases of recovery

invoked by petitioner against the defendants therein

were not necessarily identical since the respondents

were not identically circumstanced.

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

DEL ROSARIO v. FEBTC

(537 SCRA 571, 2007)

It is well established, however, that a party cannot,

by varying the form of action or adopting a different

method of presenting his case, or by pleading

justifiable circumstances as herein petitioners are

doing, escape the operation of the principle that one

and the same cause of action shall not be twice

litigated.

FACTS: PDCP extended a P4.4 million loan to DATICOR,

which that DATICOR shall pay: a service fee of 1% per

annum (later increased 6% per annum) on the

outstanding balance; 12% per annum interest; and

penalty charges 2% per month in case of default. The

loans were secured by real estate mortgages over six

(6) parcels of land and chattel mortgages over

machinery and equipment.

DATICOR paid a total of P3 million to PDCP,

which the latter applied to interest, service fees and

penalty charges. This left them with an outstanding

balance of P10 million according to PDCPs

computation.

DATICOR filed a complaint against PDCP for

violation of the Usury Law and annulment of contract

and damages. The CFI dismissed the complaint. The IAC

set aside the dismissal and declared void and of no

effect the stipulation of interest in the loan agreement.

PDCP appealed the IAC's decision to SC.

In the interim, PDCP assigned a portion of its

receivables from DATICOR to FEBTC for of P5.4 M.

FEBTC and DATICOR, in a MOA, agreed to P6.4

million as full settlement of the receivables.

SC affirmed in toto the decision of the IAC,

nullifying the stipulation of interests. DATICOR

thus

filed a Complaint for sum of money against PDCP and

FEBTC to recover the excess payment which they

computed to be P5.3 million. RTC ordered PDCP to pay

petitioners P4.035 million, to bear interest at 12% per

annum until fully paid; to release or cancel the

mortgages and to return the corresponding titles to

petitioners; and to pay the costs of the suit.

RTC dismissed the complaint against FEBTC

for lack of cause of action since the MOA between

petitioners and FEBTC was not subject to SC decision,

FEBTC not being a party thereto.

Petitioners and PDCP appealed to the CA,

which held that petitioners' outstanding obligation

(determined to be only P1.4 million) could not be

increased or decreased by any act of the creditor PDCP,

and held that when PDCP assigned its receivables, the

amount payable to it by DATICOR was the same amount

payable to assignee FEBTC, irrespective of any

stipulation that PDCP and FEBTC might have provided

in the Deed of Assignment, DATICOR not having been a

party thereto, hence, not bound by its terms.

By the principle of solutio indebiti, the CA held

that FEBTC was bound to refund DATICOR the excess

payment of P5 million it received; and that FEBTC could

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

recover from PDCP the P4.035 million for the

overpayment for the assigned receivables. But since

DATICOR claimed in its complaint only of P965,000

from FEBTC, the latter was ordered to pay them only

that amount.

Petitioners filed before the RTC another

Complaint against FEBTC to recover the balance of the

excess payment of P4.335 million.

The trial court dismissed petitioners'

complaint on the ground of res judicata and splitting of

cause of action. It recalled that petitioners had filed an

action to recover the alleged overpayment both from

PDCP and FEBTC and that the CA Decision, ordering

PDCP to release and cancel the mortgages and FEBTC to

pay P965,000 with interest became final and executory.

ISSUE: Whether FEBTC can be held liable for the balance

of the overpayment of P4.335 million plus interest which

petitioners previously claimed against PDCP in a

previously decided case

NO. A cause of action is the delict or the

wrongful act or omission committed by the defendant

in violation of the primary rights of the plaintiff. In the

two cases, petitioners imputed to FEBTC the same

alleged wrongful act of mistakenly receiving and

refusing to return an amount in excess of what was due

it in violation of their right to a refund. The same facts

and evidence presented in the first case were the very

same facts and evidence that petitioners presented in

the second case.

A party cannot, by varying the form of action

or adopting a different method of presenting his case,

or by pleading justifiable circumstances as herein

petitioners are doing, escape the operation of the

principle that one and the same cause of action shall not

be twice litigated.

SC held that to allow the re-litigation of an

issue that was finally settled as between petitioners and

FEBTC in the prior case is to allow the splitting of a

cause of action, a ground for dismissal under Section 4

of Rule 2 of the Rules of Court.

This rule proscribes a party from dividing a

single or indivisible cause of action into several parts or

claims and instituting two or more actions based on it.

Because the plaintiff cannot divide the grounds for

recovery, he is mandated to set forth in his first action

every ground for relief which he claims to exist and

upon which he relies; he cannot be permitted to rely

upon them by piecemeal in successive actions to

recover for the same wrong or injury.

Both the rules on res judicata and splitting of

causes of action are based on the salutary public policy

against unnecessary multiplicity of suitsinterest

reipublicae ut sit finis litium. Re-litigation of matters

already settled by a court's final judgment merely

burdens the courts and the taxpayers, creates

uneasiness and confusion, and wastes valuable time

and energy that could be devoted to worthier cases.

10

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

PROGRESSIVE DEVELOPMENT CORP. v. CA

(301 SCRA 367, 1991)

When a single delict or wrong is committed like

the unlawful taking or detention of the property of

another there is but one single cause of action

regardless of the number of rights that may have

been violated, and all such rights should be alleged

in a single complaint as constituting one single cause

of action. In a forcible entry case, the real issue is the

physical possession of the real property. The

question of damages is merely secondary or

incidental, so much so that the amount thereof does

not affect the jurisdiction of the court. In other

words, the unlawful act of a deforciant in taking

possession of a piece of land by means of force and

intimidation against the rights of the party actually

in possession thereof is a delict or wrong, or a cause

of action that gives rise to two (2) remedies,

namely, the recovery of possession and recovery of

damages arising from the loss of possession, but

only to one action. For obvious reasons, both

remedies cannot be the subject of two (2)

separate and independent actions, one for

recovery of possession only, and the other, for the

recovery of damages. That would inevitably lead to

what is termed in law as splitting up a cause of

action.

FACTS: PDC leased to Westin a parcel of land with a

commercial building for 9 years and 3 months, with a

monthly rental of approximately P600,000. Westin

failed to pay rentals despite several demands. The

arrearages amounted to P8,6M. PDC repossessed the

leased premises, inventoried the movable properties

found within and owned by Westin, and scheduled a

public auction for the sale of the movables, with notice

to Westin.

Westin filed a forcible entry case with the

MeTC against PDC for with damages and a prayer for a

temporary restraining order and/or writ of preliminary

injunction. A TRO enjoined PDC from selling Westin's

properties.

At the continuation of the hearing, the parties

agreed, among others, that Westin would deposit with

the PCIB (Bank) P8M to guarantee payment of its back

rentals. Westin did not comply with its undertaking,

and instead, with the forcible entry case still pending,

Westin instituted another action for damages against

PDC with the RTC.

The forcible entry case had as its cause of

action the alleged unlawful entry by PDC into the leased

premises out of which three (3) reliefs arose: (a) the

restoration by PDC of possession of the leased premises

to the lessee; (b) the claim for actual damages due to

losses suffered by Westin; and, (c) the claim for

attorneys fees and cost of suit.

On the other hand, the complaint for damages

prays for a monetary award consisting of moral and

exemplary damages; actual damages and compensatory

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

damages representing unrealized profits; and,

attorney's fees and costs, all based on the alleged

forcible takeover of the leased premises by PDC.

PDC filed a motion to dismiss the damage suit

on the ground of litis pendencia and forum shopping.

The RTC, instead of ruling on the motion, archived the

case pending the outcome of the forcible entry case.

Westin filed with the RTC an amended

complaint for damages, which was granted. It also filed

an Urgent Ex-Parte Motion for the Issuance of a TRO

and Motion for the Grant of a Preliminary Prohibitory

and Preliminary Mandatory Injunction, which were all

granted. PDCs motion to dismiss was denied.

Thus, PDC filed with the CA a special civil

action for certiorari and prohibition. But the CA

dismissed the petition. It clarified that since the

damages prayed for in the amended complaint with the

RTC were those caused by the alleged high-handed

manner with which PDC reacquired possession of the

leased premises and the sale of Westin's movables

found therein, the RTC and not the MeTC had

jurisdiction over the action of damages.

ISSUE: Whether Westin may institute a separate suit for

damages with the RTC after having instituted an action

for forcible entry with damages with the MeTC

NO. Sec. 1 of Rule 70 of the Rules of Court

provides that all cases for forcible entry or unlawful

detainer shall be filed before the MTC which shall

include not only the plea for restoration of possession

but also all claims for damages and costs arising

therefrom. Otherwise expressed, no claim for damages

arising out of forcible entry or unlawful detainer may

be filed separately and independently of the claim for

restoration of possession.

Under Sec. 3 of Rule 2 of the Revised Rules of

Court, as amended, a party may not institute more than

one suit for a single cause of action. Under Sec. 4 of the

same Rule, if two or more suits are instituted on the

basis of the same cause of action, the filing of one or a

judgment upon the merits in any one is available as a

ground for the dismissal of the other or others.

Westin's cause of action in the forcible entry

case and in the suit for damages is the alleged illegal

retaking of possession of the leased premises by PDC

from which all legal reliefs arise. Simply stated, the

restoration of possession and demand for actual

damages in the case before the MeTC and the demand

for damages with the RTC both arise from the same

cause of action, i.e., the forcible entry by PDC into the

least premises. The other claims for moral and

exemplary damages cannot succeed considering that

these sprung from the main incident being heard before

the MeTC. Jurisprudence says that when a single delict

or wrong is committed like the unlawful taking or

detention of the property of the another there is but

one single cause of action regardless of the number of

rights that may have been violated, and all such rights

should be alleged in a single complaint as constituting

one single cause of action. In a forcible entry case, the

real issue is the physical possession of the real

11

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

property. The question of damages is merely secondary

or incidental, so much so that the amount thereof does

not affect the jurisdiction of the court. In other words,

the unlawful act of a deforciant in taking possession of a

piece of land by means of force and intimidation against

the rights of the party actually in possession thereof is a

delict or wrong, or a cause of action that gives rise to

two (2) remedies, namely, the recovery of possession

and recovery of damages arising from the loss of

possession, but only to one action. For obvious reasons,

both remedies cannot be the subject of two (2) separate

and independent actions, one for recovery of

possession only, and the other, for the recovery of

damages. That would inevitably lead to what is termed

in law as splitting up a cause of action.

What then is the effect of the dismissal of the

other action? Since the rule is that all such rights should

be alleged in a single complaint, it goes without saying

that those not therein included cannot be the subject of

subsequent complaints for they are barred forever. If a

suit is brought for a part of a claim, a judgment

obtained in that action precludes the plaintiff from

bringing a second action for the residue of the claim,

notwithstanding that the second form of action is not

identical with the first or different grounds for relief are

set for the second suit. This principle not only embraces

what was actually determined, but also extends to

every matter which the parties might have litigated in

the case. This is why the legal basis upon which Westin

anchored its second claim for damages, i.e., Art. 1659 in

relation to Art. 1654 of the Civil Code, not otherwise

raised and cited by Westin in the forcible entry case,

cannot be used as justification for the second suit for

damages.

CGR CORP. V. TREYES

(522 SCRA 765, 2007)

Petitioners filing of an independent action for

damages grounded on the alleged destruction of

CGRs property, other than those sustained as a

result of dispossession in the Forcible Entry case

could not be considered as splitting of a cause of

action.

FACTS: CGR Corporation, Herman Benedicto and

Alberto Benedicto, petitioners, claim to have occupied

37 ha. of public land in Negros Occidental, pursuant to a

lease agreement granted to them by the Secretary of

Agriculture for a period of 25 years (to last October

2000 to December 2024). On November 2000, however,

respondent Treyes allegedly forcibly and unlawfully

entered the leased premises and barricaded the

entrance to the fishponds of the petitioners. Treyes and

his men also harvested tons of milkfish and fingerlings

from the petitioners ponds.

Petitioners then filed a complaint for Forcible

Entry with the MTC. Another complaint to claim for

damages was also filed by the petitioners against the

same respondent Treyes grounded on the allegations

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

that Treyes and his men also destroyed and ransacked

the Chapel built by petitioner CGR Corporation and

decapitated the heads of the religious figures.

ISSUE: Whether during the pendency of a separate

complaint for Forcible Entry, the petitioner can

independently institute and maintain an action for

damages which they claim arose from incidents

occurring after the forcible entry of Treyes and his men

YES. The only recoverable damages in the

forcible entry and detainer cases instituted first by the

petitioners with the MTC are the rents or fair rental

value of the property from the time of dispossession by

the respondent. Hence, other damages being claimed by

the petitioners must be claimed in another ordinary

civil action.

It is noteworthy that the second action

instituted by the petitioners (complaint for damages)

have NO direct relation to their loss of possession of the

leased premises which is the main issue in the first

action they instituted. The second action for claim of

damages had to do with the harvesting and carting

away of milkfish and other marine products, as well as

the ransacking of the chapel built by CGR Corp. Clearly,

the institution of the two cases is not a splitting of a

cause of action, since both are concerned with entirely

different issues.

ENRIQUEZ v. RAMOS

(7 SCRA 265, 1963)

An examination of the first complaint filed against

appellant in CFI showed that it was based on

appellants' having unlawfully stopped payment of

the check for P2,500.00 she had issued in favor of

appellees; while the complaint in the second and

present action was for non-payment of the balance

of P96,000.00 guaranteed by the mortgage. The

claim for P2,500.00 was, therefore, a distinct debt

not covered by the security. The two causes of

action being different, section 4 of Rule 2 does not

apply.

FACTS: Rodrigo Enriquez and the Dizon spouses sold to

Socorro Ramos 11 parcels of land for P101,000. Ramos

paid P5,000 downpayment, P2,500 in cash, and with a

P2,500.00 check drawn against PNB, and agreed to

satisfy the balance of P96,000.00 within 90 days. To

secure the said balance, Ramos, in the same deed of

sale, mortgaged the 11 parcels in favor of the vendors.

Ramos mortgaged a lot on Malinta Estate as additional

security, as attorney-in-fact of her four children and as

judicial guardian of her minor child.

Ramos failed to comply with the conditions of

the mortgage, so an action for foreclosure was filed by

the vendors-mortgagees. Ramos moved to dismiss,

alleging that the plaintiffs previously had filed action

against her in the CFI of Manila for the recovery of

P2,500.00 paid by check as part of the down payment

on the price of the mortgaged lands; that at the time

12

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

this first suit was filed, the mortgage debt was already

accrued and demandable; that plaintiffs were guilty of

splitting a single cause of action, and under section 4 of

Rule 2 of the Rules of Court, the filing of the first action

for P2,500.00 was a defense that could be pleaded in

abatement of the second suit.

CFI of Quezon City denied the motion to

dismiss. Defendant Ramos re-pleaded the averments as

a special defense in her answer. The CFI ruled against

defendant Ramos; ordered her to pay P96,000.00, with

12% interest, attorney's fees, and the costs of the suit;

and further decreed the foreclosure sale of the

mortgaged properties in case of non-payment within 90

days. Ramos appealed directly to SC,

ISSUE: Whether there was splitting of cause of action

NO, there is no splitting of cause of action in

this case. An examination of the first complaint filed

against appellant in CFI showed that it was based on

appellants' having unlawfully stopped payment of the

check for P2,500.00 she had issued in favor of

appellees, while the complaint in the second and

present action was for non-payment of the balance of

P96,000.00 guaranteed by the mortgage. The claim for

P2,500.00 was, therefore, a distinct debt not covered by

the security. The two causes of action being different,

section 4 of Rule 2 does not apply.

Remedy against splitting a single cause of action

(a) Motion to dismiss (Sec 1 [e] or [f], Rule 16)

Within the time for but before filing the

answer to the complaint or pleading asserting

a claim, a motion to dismiss may be made on

any of the following grounds:

xxx

(e) That there is another action pending

between the same parties for the same cause;

(f) That the cause of action is barred by a

prior judgment or by the statute of limitations

xxx

(b) Answer alleging affirmative defense (Sec. 6,

Rule 16)

If no motion to dismiss has been filed, any of

the grounds for dismissal provided for in this

Rule may be pleaded as an affirmative defense

in the answer and, in the discretion of the

court, a preliminary hearing may be had

thereon as if a motion to dismiss had been

filed.

NOTE: As to which action should be dismissed (the first

or second one) would depend upon judicial discretion

and the prevailing circumstances of the case.

Joinder of causes of action

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

Joinder of causes of action is the assertion of as many

causes of action as a party may have against another in

one pleading. It is the process of uniting two or more

demands or rights of action in one action.

This is merely permissive, NOT compulsory,

because of the use of the word may in Sec. 5,

Rule 2.

It is subject to the following conditions:

(a) The party joining the causes of action shall

comply with the rules on joinder of parties;

i.

The right to relief should arise out of

the same transaction or series of

transaction, and

ii.

There exists a common question of

law or fact. (Sec. 6, Rule 3)

(b) The joinder shall not include special civil

actions or actions governed by special rules;

Example: An action for claim of

money cannot be joined with an

action for ejectment, or with an

action for foreclosure.

(c) Where the causes of action are between the

same parties but pertain to different venues

or jurisdictions, the joinder may be allowed in

the RTC provided

i.

one of the causes of action falls

within the jurisdiction of said court,

and

ii.

the venue lies therein; and

(d) Where the claims in all the causes of action

are principally for recovery of money, the

aggregate amount claimed shall be the test of

jurisdiction. (Sec. 5, Rule 2)

Misjoinder of causes of action

Misjoinder of causes of action is NOT a ground for

dismissal of an action. A misjoined cause of action may

be severed and proceeded with separately:

(a) on motion of a party, or

(b) on the initiative of the court. (Sec. 6, Rule 2)

FLORES v. MALLARE-PHILLIPPS

(144 SCRA 277, 1986)

Application of the Totality Rule under Sect. 33(l)

BP129 and Sect. 11 of the Interim Rules is subject

to the requirements for the Permissive Joinder of

Parties under Sec. 6 of Rule 3.

In cases of permissive joinder of parties,

the total of all the claims shall be the first

jurisdictional test. If instead of a joinder, separate

actions are filed by or against the parties, the

amount demanded in each complaint shall be the

second jurisdictional test.

FACTS: Binongcal and Calion, in separate transactions,

purchased truck tires on credit from Flores. The two

allegedly refused to pay their debts, so Flores filed a

13

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

complaint where the first cause of action was against

Binongcal for P11, 643, and the second was against

Calion for P10, 212. Binongcal filed a Motion to Dismiss

on the ground of lack of jurisdiction since under Sec.

19(8) of BP129 RTC shall exercise exclusive original

jurisdiction if the amount of the demand is more than

P20, 000, and that the claim against him is less than

that amount. He averred further that although Calion

was also indebted to Flores, his obligation was separate

and distinct from the other, so the aggregate of the

claims cannot be the basis of jurisdiction. Calion joined

in moving for the dismissal of the complaint during the

hearing of the motion. Petitioner opposed the Motion to

Dismiss. RTC dismissed the complaint for lack of

jurisdiction.

ISSUE: Whether RTC has jurisdiction over the case

following the Totality Rule

YES. The Totality Rule (under Sec. 33 of

BP129 and Sec. 11 of the Interim Rules) applies not

only to cases where two or more plaintiffs having

separate causes of action against a defendant join in a

single complaint, but also to cases where a plaintiff has

separate causes of action against two or more

defendants joined in a single complaint. However, the

said causes of action should arise out of the same

transaction or series of transactions and there should

be a common question of law or fact, as provided in Sec.

6 of Rule 3.

In cases of permissive joinder of parties, the

total of all the claims shall be the first jurisdictional test.

If instead of joining or being joined in one complaint,

separate actions are filed by or against the parties, the

amount demanded in each complaint shall be the

second jurisdictional test.

In the case at bar, the lower court correctly

held that the jurisdictional test is subject to the Rules

on Joinder of Parties pursuant to Sec. 5 of Rule 2 and

Sec. 6 of Rule 3 of the Rules of Court. Moreover, after a

careful scrutiny of the complaint, It appears that there

is a misjoinder of parties for the reason that the claims

against Binongcal and Calion are separate and distinct

and neither of which falls within its jurisdiction.

UNIWIDE HOLDINGS, INC. v. CRUZ

(529 SCRA 664, 2007)

Exclusive venue stipulation embodied in a contract

restricts or confines parties thereto when the suit

relates to breach of said contract. But where the

exclusivity clause does not make it necessarily

encompassing, such that even those not related to

the enforcement of the contract should be subject

to the exclusive venue, the stipulation designating

exclusive venues should be strictly confined to the

specific undertaking or agreement.

FACTS: Uniwide Holdings, Inc. (UHI) granted Cruz, a

5yr. franchise to adopt and use the "Uniwide Family

MENDEZ, IVAN VIKTOR (2D, 13)

Store System" for the establishment and operation of a

"Uniwide Family Store" in Marikina. The agreement

obliged Cruz to pay UHI a P50,000 monthly service fee

or 3% of gross monthly purchases, whichever is higher,

payable within 5 days after the end of each month

without need of formal billing or demand from UHI. In

case of any delay in the payment of the monthly service

fee, Cruz would be liable to pay an interest charge of

3% per month.

It appears that Cruz had purchased goods

from UHIs affiliated companies FPC and USWCI. FPC

and USWCI assigned all their rights and interests over

Cruzs accounts to UHI. Cruz had outstanding

obligations with UHI, FPC, and USWCI in the total

amount of P1,358,531.89, which remained unsettled

despite the demands made.

Thus UHI filed a complaint for collection of

sum of money before RTC of Paraaque Cruz on the

following causes of action: (1) P1,327,669.832 in actual

damages for failure to pay the monthly service fee; (2)

P64,165.96 of actual damages for failure to pay

receivables assigned by FPC to UHI; (3) P1,579,061.36

of actual damages for failure to pay the receivables

assigned by USWCI to UHI; (4) P250,000.00 of

attorneys fees.

Cruz filed a motion to dismiss on the ground

of improper venue, invoking Article 27.5 of the

agreement which reads:

27.5 Venue Stipulation The Franchisee

consents to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of

Quezon City, the Franchisee waiving any other venue.

Paraaque RTC granted Cruzs motion to

dismiss. Hence, the present petition.

ISSUE: Whether a case based on several causes of action

is dismissible on the ground of improper venue where

only one of the causes of action arises from a contract

with exclusive venue stipulation

NO. The general rule on venue of personal

actions provides actions may be commenced and tried

where the plaintiff or any of the principal plaintiffs

resides, or where the defendant or any of the principal

defendants resides, or in the case of a nonresident

defendant, where he may be found, at the election of the

plaintiff. The parties may also validly agree in writing

on an exclusive venue. The forging of a written

agreement on an exclusive venue of an action does not,

however, preclude parties from bringing a case to other

venues.

Where there is a joinder of causes of action

between the same parties and one action does not arise

out of the contract where the exclusive venue was

stipulated upon, the complaint, as in the one at bar, may

be brought before other venues provided that such

other cause of action falls within the jurisdiction of the

court and the venue lies therein.

Based on the allegations in petitioners

complaint, the second and third causes of action are

based on the deeds of assignment executed in its favor

by FPC and USWCI. The deeds bear no exclusive venue

stipulation with respect to the causes of action

14

CIVIL PROCEDURE REVIEWER

thereunder. Hence, the general rule on venue applies

that the complaint may be filed in the place where the

plaintiff or defendant resides.

It bears emphasis that the causes of action on

the assigned accounts are not based on a breach of the

agreement between UHI and Cruz. They are based on

separate, distinct and independent contractsdeeds of

assignment in which UHI is the assignee of Cruzs

obligations to the assignors FPC and USWCI. Thus, any

action arising from the deeds of assignment cannot be

subjected to the exclusive venue stipulation embodied

in the agreement.

Exclusive venue stipulation embodied in a

contract restricts or confines parties thereto when the

suit relates to breach of said contract. But where the

exclusivity clause does not make it necessarily

encompassing, such that even those not related to the

enforcement of the contract should be subject to the

exclusive venue, the stipulation designating exclusive

venues should be strictly confined to the specific

undertaking or agreement. Otherwise, the basic

principles of freedom to contract might work to the

great disadvantage of a weak party-suitor who ought to

be allowed free access to courts of justice.

What is the totality rule?

Where the claims in all the causes of action are

principally for recovery of money, the aggregate

amount claimed shall be the test of jurisdiction. (Sec. 5,

Rule 2)

PARTIES TO CIVIL ACTIONS (RULE 3)

Parties (Sec. 1, Rule 3)

(1) Plaintiff

The plaintiff is the claiming party or the original

claiming party and is the one who files the

complaint.

It may also apply to a defendant who files

a counterclaim, a cross-claim or a third