Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

CHETVERUKHIN ALEXANDERS. Some Theoretical Aspects of Old Egyptian Nominal Sentence. Structure and Semantics. 1990.17.12

Загружено:

sychev_dmitryАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CHETVERUKHIN ALEXANDERS. Some Theoretical Aspects of Old Egyptian Nominal Sentence. Structure and Semantics. 1990.17.12

Загружено:

sychev_dmitryАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Altorientalische Forschungen

ALEXANDER

S.

17

I 1990

3-17

CHETVERUKHIN

Some Theoretical Aspects of Old Egyptian Nominal Sentence.

Structure and Semantics

The interest for the nominal sentence (NS) theory within the modern general

linguistic methods, mostly those of generative and semantic syntax, does not

diminish at all now; just the opposite, it does show a steady increase in modern

egyptology. One can see it, even not aiming to tackle the problem, just from the

abundant literature of recent years. First of all, we have in mind the following

works: a number of articles in the "Studies Presented to Hans Jakob Polotsky",

articles by Westendorf and Schlachter (the latter being an answer from a specialist in general linguistics to the problems set forth by the former) in the "Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Gttingen", Schenkel in "Festschrift Westendorf", then Callender "Studies in the Nominal Sentence in Egyptian and Coptic" and critics thereof byAnneBiedenkopf-Ziehner andW. Schenkel,

furthermore Roeder in "Gttinger Miszellen", the contents of "Crossroad. Chaos

or the Beginning of a New Paradigm", and Depuidt in "Orientalia".!

This interest is by no means a kind of fashion epidemic : the very fact that the

Egyptian verbal finite forms are possessive by their structure (but the so-called

Old Perfective, or the Quality and State Form after N. S. Petrovsky) inevitably witnesses to the common orientation of the Egyptian syntactic patterns

towards the nominal one. This is evident from the well-known monograph by

' D . W . Y o u n g (ed.), Studies Presented to H a n s Jakob Polotsky, Beacon Hill 1981;

W. Westendorf and W. Schlachter, in: Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften

in Gttingen 1981, Nr. 3, 7 7 - 7 9 , and Nr. 4, 1 0 3 - 1 1 9 ; W. Schenkel, Fokussierung.

ber die Reihenfolge von Subjekt und Prdikat im klassisch-gyptischen Nominalsatz, in: Studien zu Sprache und Religion gyptens (Festschrift W. WTestendorf), Gttingen 1984; J'. B. Callender, Studies in the Nominal Sentence in Egyptian and Coptic,

Berkeley 1984 (University of California Publications, Near Eastern Studies 24); Anne

Biedenkopf-Ziehner in: Enchoria 13 [1985], 2 1 7 - 2 3 2 ; W. Schenkel, Spezifitt"

der Schlssel zum gyptisch-koptischen Nominalsatz?, in: BiOr 52 [1985], 256265;

H. Roeder, Die Prdikation im Nominalen Nominalsatz. Ein logisch-semantischer

Ansatz, in: GM 91 [1986], 1 - 7 7 ; G.'Englund - P. J. Frandsen (ed.), Crossroad. Chaos

or the Beginning of a New Paradigm. Papers from the Conference on Egyptian Grammar. Helsingor 2 8 - 3 0 May 1986, Copenhagen 1986 (The Carsten Niebuhr Institute

of Ancient Near Eeast Studies Publications 1); L. Depuidt, The Emphatic Nominal

Sentence in Egyptian and Coptic, in: Orientaba 56 [1987], 3554. See also our recent

articles: Jea noAXO^a L O Y I E H H I O eraneTCKoro npe^jioHeHHH, IlcTopuH

ApeBiiero H cpe^HeBeKOBoro BocTOKa, Moscow 1987, 6483; CoBpeMeHHoe cocTOHHHe

nayneHHH CTapoenineTCKoro npejio>KeHHH, ibid. 84100; MHTepnpeTaiiHH Asyx

OCHOBHHX 10 ^ 3, ^ Cpe/JHeBeKOBhltt CT0K, Moscow 1987, 3149.

*

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

Alexander S. Chetveriikliin

Junge "Syntax der mittelgyptischen Literatursprache".- The general reason

of such a phenomenon seems to be a very archaic typological structure of

Egyptian, presumably close to that of the active typology languages.3

Trivial as it is, the languages of active and ergative typology often have possessive predicative constructions.4 However, the profound understanding of

various Egyptian language phenomena is expected to be deducible anyway

from the NS on different levels of linguistic analysis. And vice versa, the NS analysis is essentially depending on the results gained in the process of all the other

spheres in the Egyptian grammar study, up to the obligatory taking into consideration both comparative linguistic material and comprehensive data of

general linguistic typology. The most complicated field of Egyptian still remains that of morphology, despite verily heroic efforts by such outstanding scholars as K . Sethe, W. F. Albright, J . Vergote, W. Vycichl, G. Fecht and J . Osing.

Nevertheless the problem of "the common denominator" is left open.

The problems above naturally call into existence the issue of parts of speech.

Indeed, whatever method of syntactic analysis be applied, in any spoken language the morphological nature of the constituents is quite clear, or can easily be

defined; they may be kept in the background and put forward if necessary.

Nothing of the kind appears in Egyptianthe problem had already been foresaid by Gunn in a review on the well-known work of Faulkner. 5 So, when speaking of the Egyptian material, we would prefer to use mostly not the conventional

terms (not really supported by our actual knowledge), such as "Adjective",

"Participle" and "Substantive" (except for "Pronouns" (Pr), personal (pers)

and demonstrative (dem)), the term " S t e m " (St) will be understood as "Quality",

"Agentive" (i.e. having verbal semantics with an ex(or im)plicite agens), and

"Substantival" (a form substantivized from any part of speech, even from syntagmata but Pr.). Thus, we would prefer "Substantival Stem" (St s) instead of

"Substantive", "Quality Stem" (St q) for "Adjective", "Agentive Stem" (St ag)

in place of "Participle". The totality of the actual forms termed as "Stems"

differentiates as follows :

1) semantically,

2) by combinability,

3) functionally on different levels of syntactic analysis,

4) morphologically (partly explicit),

and at last but not in the least by

5) spellingalways bearing in mind that the Egyptian language exists

for us only as a written one with a complicated but always very significant sys2

F . Junge, Syntax der mittelgyptischen Literatursprache. Grundlagen einer Strukturtheorie, Mainz a. Rh. 1978.

A . C . H e T B e p y x H H , o n p e n e J i e H H i o HATIKA C T a p o r o COCTOHHHH, -

MeHHbie nauHTHHKH H npoSjieMM HCTopHH KyjibTypu HapoOB BocTOKa (=).

X X rosHiHaH Haymaa ceccHH JIO HB AH CCCP (OKJiaflu H coo6meHHH), Moscow 1985,

lacTb , 8394; 3 ernneTCKoro nsuita KOHTCHCHBHO ( s e e p . 17 ).

See G . A . Klimov's works: ^ OME TeopHH apraTHBHOcnx, Moscow 1 9 7 3 ; THHOJIO H3HK0B aKTHBHOrO CTpOH, MOSCOW 1 9 7 7 ;

IIpHHIJHnH KOHTenCHBHOfi THIIOJIOrHH,

Moscow 1983.

B . Gunn: R . O. Faulkner, The Plural and Dual in Old Egyptian, Brussels 1929 ( 53,

64), in: J E A 19 [1933], 106.

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

Old Egyptian Nominal Sentence

tern of orthography. This peculiarity shows itself in different ways, one of which

being the system of graphical determinatives. It can be evinced by concrete examples, interesting not only as such, but in that they also demonstrate the Egyptian native mode of estimating the lexical inventory marked above as " S t e m s " .

Thus, the set named as St s tends to be written with the graphic determinative

of the concrete object meant, which was originally a picture of the thing mentioned. It was a general tendency in tomb inscriptions for imitativeness of the

signsthis was justified by the Egyptian idea of the Beyond, where all that is

depicted and mentioned in the inscriptions come to life again and act for the

tomb's owner, as if it were in reality, 6 let alone that the pictures and images of

the tomb in their turn played a role of determinatives for the inscription. Outside the tomb inscriptions the concrete object picture as a determinative grew

more abstract, mainly due to rapid forms of writing (the hieratic and demotic),

finally transformating into a current symbol of a class of related objects. In

principle, the determinative was now aimed at linking the word-form to a concrete semantic totality of objects, if the connexion between them seemed to be

apparent. As a result, St q was either deprived of any graphic determinative, or

equipped with a sign classifying the stem in accordance with the emotional reaction of a person being in the condition implicated by the meaning of the given

S t q : " j o y " , "distress", "prostration" etc.as a determinative, a human figure

or a part thereof is depicted in its proper posture. The verbal stems had determinatives depicting human or animal organs producing the fiction, or the instrument where with the action used to be produced, in the case of a verb of

action, not of state; the latter was also determined by the corresponding St q

(i.e., derived from the same root). St ag could contain, along with the verbal

determinative, that of agens, pointing to a human being or a deity. Prepositions,

particles and pronouns as a rule had no determinatives at all, because the

first person suffixal pronoun was expressed by an ideogram, not a determinative.

The fundamental principle in elaborating the graphic determinative system was

that of mental association, whatever forms it could take. According to the principle in question, not only quality stems, but even some substantival (not of the

same roots) and verbal ones might be grouped togetherthe latter if the action

or state designated was associated with a certain human emotional reaction.

For example : under the determinative " b a d " (sign "sparrow"G 37 of Gardiner's

Sign-list) the following root morphemes are grouped: nds "small", hns "narrow",

bjn " b a d " , sw "empty", mr "ill, diseased"all these being St q, wherefrom some

St s could also be derived: nds "commoner", bjn.t "evil" etc., this is naturally

so, but also Bq "perish" is classed herea "pure" verbal St, quite independent.

For the first glance it is not clear why it was the sign of sparrow that acquired

such meaning. One may reproduce, however, the following semantic implication: "sparrow" "crops damager" "bad, harmful" (and simultaneously " a n

empty field", "small, insufficient harvest") abstract notion of graphic determinative as defining "something bad, harmful, unhappy, insufficient, perishing".

In any case, the highly developed determination system is a secondary one, of

6

A new explanation of the tomb images and pictures see in: A. O. BojibuiaKOB, IIpeflCTaB-

.leHiie o ABOitHHKe Craporo uapcTBa, in: "VDl 181 [1987], 336.

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

Alexander S. Chetvonikhin

higher rank of the overworked ideography. In Old Egyptian it was still in the

process of formation, taking its proper shape only in the Middle Egyptian (Classical) written language.

The Egyptian system of graphic determinatives enables us to state that the

Egyptians distinguished the root morpheme from the auxiliary morpheme, and

full-semantic word-forms from their substitutespronouns. The Egyptian thought

did not imply abstracting basic categories, namely the substantive and the verb,

both notions being not so far abstracted as to lead to elaborating two opposing

general determinatives. The reason of the phenomenon is probably concealed in

the Egyptian mode of thinking, though it might be also maintained by the

morphological phenomena themselves : the principles of verb and noun morphological differentiation being utterly unlike the Indoeuropean languages, where

it seems to be more obvious than in Egyptian. It goes without saying in any case,

that in the long run, along with other graphical methods, the Egyptian system

of graphical determination somehow also compensated for a phonological underdevelopment of the writing system's means which were based primarily on the

consonantal (and sonantic) skeleton of the root morpheme.7 Indeed, there are

various ways to investigate the Egyptian writing system, but the semantic one

appears to be the most fruitful, if we want not only to understand the system as

a whole, but find the right way into the Egyptian mode of mentality. It is this

approach that was recognized as most fruitful by our late great master of Egyptology, Yu. Y a . Perepiolkin.

Through lack of special graphemes for vowel representation, the Egyptian

writing system conceals many features of morphology, which are partially reconstrutable from a pool of various data. In written Egyptian we have but

hints to the real morphological structure, and first of all, markers of gender and

number. All stems constituing N S differentiated them. But while St s is quite

independent of its position and function, St q,ag differentiates gender and number when occupying the second or third position in the NS, and that only in

Old Egyptian (OE). In the first position there is no grammatical congruence

with the second constituent St s, and St q,ag look as if they were sg.m. It is

indeed not excluded, that we have here a peculiar use of (proto-)masculine sg.,

which is to be taken into account when analysing Egyptian gender and number

markers.8 The quality-verb-stems being present, the N S with St q is hard to

distinguish from the verbal sentence9this peculiarity might show the activeergative typology of OE and ME. 10 The other N S features pertaining to the old

stage of the Egyptian language development (i.e. OSE, comprising OE and

M E ) are: basic patterns X pw ( = Y ) and X pw Y , the pattern Y X pw being

7

H. C. rteTpoBCKHii, 3 B y K 0 B u e 3naKH e r m i e T C K o r o i w c b M a K a n CHCTeina, Moscow 1978.

See also P. Vernus, L'criture hiroglyphique: une criture duplice?, and the literature

cited there, in: Confrontations, Cahiers 16, Autumne 1986 an offprint kindly presented by its author.

See also: F. Aspesi, La distinzione dei generi nel nome anticoegiziano e semitico, Florence 1977.

A. C. H e T B e p y x i i H , Teopna e r u n e T C K O r o n p e a n o J K e m i H . I V .

CiicTeMaTH3aijHH

10

Mcueaei

eruneTCKOro

n p e j . i o w e H H H (in p r i n t ) .

See our fn. 3.

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

Old Egyptian Nominal Sentence

the rarest one;' 1 using of Pr pers and dem as constituents of NS paradigm combining with each other (see below) ; a plenty of patterns with actualizing particles1'-, etc., the X and Y being constituents (principal members) of NS. The common logic-grammatical analysis of some of these patterns has been made previously.13 The absence of any explicit system of grammatical determination

(not to be confused with the graphical determination above!) in the written

OSE should also be taken into consideration.1/1

Speaking of the NS constituents, it should be remembered that St q,ag as the

second constituent originally agreed in gender (perhaps both in gender and

number) with the first constituentSt s. This phenomenon was no longer productive towards the end of OE. 15 Thus a formal dissociation appeared between

NS and the attributive non-predicative syntagmata. This correlates with the

formation of NS with an invariable logic-grammatical subject pw: the pronominal form is, in fact, fossilized in m.sg. (sf. above on the congruence of first constituent of the NS), though somewhat earlier the demonstrative of "the -wseries" was yet variable, originally agreeing in gender and number with the X.

Traces thereof can be found in the Pyramid Texts ( = PT). 16 All the facts exhibit not only the formal dissociation between the NS constituents, but also the

exceptional importance of the suprasegment means meeting the requirements

for the sentence, the intonation in particular, a conclusion which seems inevitable. And the second, not obvious, conclusion: a levelling of grammatical (not

logic-grammatical!) predicate forms of St q,ag in accordance with that of sg.m.

irrespective of its position in the NS structure. The impulse to such a generalization was given by the masculine form of the first NS constituent in patterns

I St q,ag + 2 St s.

It is known that the attributive syntagm preserved the concord up to the

later period of the Egyptian written language development. But an impression

may arise, that ME shows a more consecutive agreement here than even OE.

If we treat the problem in a purely linguistical way, leaving aside the written

system, this statement seems wrong, being utterly against the trends of histoII

12

Id., JIorHKO-rpaMMaTHiecKH aHajiHS flByx C J I O W H M X KOHCTpyKUHft (PT 133 f H 586b),

X V I I / I L ,

1983, 86-93. The patterns X Y are represented only in two

cases: 1) both X and Y are attributive syntagmata, co-ordinated or not, or 2) X is Pr

pers ind or interrogative pronoun.

Id., A K T Y A J I N 3 A T O P B I >. To be published in "IlaJieCTHHCKHK COpHHK" 3 1 .

npeaiiOJKeHHH " M M H + yKa3aTeJii>X I I I . , 1977, 175179; O rjiaBHHx i n e H a x CTapoerHNETCKORO N P E A J I O H I E H H H ,

XIV/II., 1979, 259265; C N H T A K C H H E C K A N ( F L Y M A N Y K A E A T E J I B H O R O pw C T A P O E M N E T C K O M npeJioweHHH, in: V D 158 [1981], 97-111; see also our fn. 1, 3, 9, 14, 19, 23, 25.

14 Id., JIorHKO-rpaMMaTHHecKHft npennaT CTapoerwneTCKOM npeaJioHteHHH M

13

Id., IIponcxo>K;ieHHe ermieTCKoro

Hoe MecTOMMeHHe",

KaTeropmi

naflewa

h aeTepMHHai(HH poacTBeHHux H3tiKax,

flpeBHH

cpeflHeeeKO-

HcTopnH, , Moscow 1 9 8 3 , 1 0 6 1 2 0 .

E . Edel, Altgyptische Grammatik, B d . I - I I , R o m e 1955, 1964, 362-363, 632-633

( =EAG).

PTThe Old E g y p t i a n Pyramid Texts, the main edition : K . Sethe. Die altgyptischen Pyramiden texte, 4 vols., Leipzig 19081922, also posthumously his: bersetzung und K o m m e n t a r zu den altgyptisehen Pyramidentexten, 6 vols. Glckstadt

Hamburg 1935-1962.

BUIT B O C T O K .

15

16

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

Alexander S. Chetverukhin

rical development of the Egyptian language. Actually we have here an apparent extra-linguistic phenomenon: the economy in labour put into hewing,

trimming and grinding of the stone surface, transportation of stone itself, and

making hieroglyphs on it, especially in the Old Kingdom : each extra sign means

a "superfluous" cubic capacity of wrought stone. As for the Egyptian writing

system in its entirety, the principle of economy applied not only to the monumental kinds of writingeconomy in signs, in order to save not so much the material, as time, shows itself also in the cursive kinds of writing where brief and

defective spellings are often encountered. They may be divided into two main

categories, the occasional, and the usualthe latter could be termed "universally recognized abbreviations", e.g. rt instead of the current rmt (OE "man",

ME "people", later again "man").17 It is the considerations of economy that lie

at the base of such graphical methods as haplography and writing in split columns ; it is also the same reason that often enabled the scribe to write jsjh.t nb in

place of jlh.t nb.t, because in the abbreviation

the marker of gender (.t) was

graphically generalizedas early as in OEboth for the St s (js/h.t), and for the

St q (rib.t), the original grammatical agreement being hidden by the spelling in

question. The actual loss of fem. .t is to be postulated for a much later period than

the OE. In later times a curiuos coincidence however took place: the misleading

("non-grammatical") spelling acquired the true content due to the actual fall

of external morphological markers: first in St q,ag in attributive function, then

also in St s, rudimentally kept only in steady word-combinations which then

transformed into compound-forms. The rudimentary external morphological

system, ever so much contracted as compared with that of Late Egyptian, survived in Coptic, the general tendency showing a re-building of the Egyptian

morphological markers system from the suffixional towards the prefixional

one.

Nothing of the kind mentioned for more later periods took place in OSE considering morphological treatment of the NS principal members. First of all, the

absence of concord of 2 St q,ag with 1 St s is an evident fact of language 18 , not of

orthography, because it is very difficult to suppose that a grammatical marker

was generalized in spelling according to St q,ag, while the same did not happen

in the attributive syntagm. Second, this could not be a result of the loss of outer

morphological markers, since it occurred much later. It is a tendency to formal

disconnection of predicative and non-predicative (attributive) syntagmata that

played the leading role, not the auslaut morphemic reduction above.

For the purposes of the following analysis let us separate the NS paradigm

into two main groups, or generalized schemes :

The first scheme (I), where the second constituent is always pw (rarely tw

and nw), and the first position can be substituted for any St or Pr. 19

17

18

19

T h e principles of e c o n o m y observed in P T are traced t o in vol. IIITV of Sethe's P T

edition, see our fn. 16.

A. H . Gardiner, E g y p t i a n Grammar, 2nd ed. London 1950, 1 3 5 - 1 3 7 , 3 7 3 - 3 7 4

( = G E G ) ; G. Lefebvre, Grammaire de l'gvptien classique. Cairo 1940, 625, 632

( = LGEC).

T h e peculiar usage of dependent pronouns as the first constituent is here eliminated

and up t o t h e question it is to consult in: W. B a i t a , D a s Personalpronomen der wjBrought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

Old E g y p t i a n Nominal Sentence

The second scheme (II) where both constituents are any St or Pr, that is the

scheme with equally (or nearly so) substitutive constituents. Note that our "1"

and "2" show the ordinal number of the constituent. It can be put down as

follows :

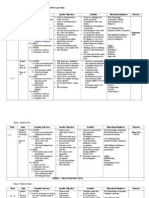

I. 1 St s, q, ag (Pr pers ind/Pr dem) + ?m;

II. 1 St s, q, ag (Pr pers ind/Pr dem) +

+ ) 2 St, s, q, ag (Prpers ind, dep/

Pr dem).

The scheme II manifests itself in three ways (a special case with Pr dem, see

below) :

A. 1 St s, q, ag + 2 Pr pers dep/ind

. 1 Pr pers ind (+pw) + 2 St s, q, ag

C. 1 Pr pers ind (+pw) + 2 Pr pers ind/dep,

wherein "( +pw)" denotes a quasi-optional character of Pr dem pw, acting in "I"

as a real logic-grammatical subject and thus being the second constituent. In

"II" (B.C.) pw became formal, so it is not (no more) a constituent here, but an

auxiliary component. The dual of pronouns is rare and in any case irrelevant for

the analysis. The scheme I. 1 Pr pers ind+ 2 pw may be represented as:

1. c.

2. m.

2. f.

3. m.

3. f.

Sgjnk pw

tw.tjnt.k

tm.tlnt.t

sw.tjnt.f

st.tint.s

PI.

pw

pw

pw

pw

1. c.

inn/jnn pw

2. c.

nt.tn pw

3. c.

nt.sn pw

Here the following should be noted: In OE the "earlier" pronominal forms are

mostly used, namely tw.tst.t. The "pl.c." forms except I.e. are only imaginary

as can be deduced from Afrasian comparative data. For OE an internal "u"

for the masculine and "i" for the feminine in the suffixal and dependent Pr pers

should probably be reconstructed, keeping in mind that the paradigm of Pr pers

ind pi. (2. and 3. pers) consists of a morpheme nt 4- suffixal Pr pers, as the corresponding forms of sg. A similar vocalization may with caution be proposed

for the ME forms, where their drawing together may be expected. Their full

convergence might have taken place somewhat later, the reason being a weakened position of the differentiating vowel. Note, that here, as above in the case

of jsjh.t nb.t, there took place a graphical coincidence which can bring one to an

utterly wrong conclusion concerning the OSE grammatical structure. Actually,

both cases are a result of graphical "generalization". The "early" Pr pers ind

variant tw.tst.t is of the same origin as the Akkadian independent direct-object and genitive Pr pers.20 The morph nt of the Pr pers ind is perhaps related,

20

R e i h e als Pi'oklitikon im adverbiellen Nominalsatz, in: ZS 112 [1985], 94104, bes.

103: Zusammenfassend kann danach festgestellt werden, da die besprochene Satzkonstruktion sw sdm.f etc. ob als Nebensatz, als Charakterisierung, als direkte R e d e

oder als Kontinuativ gebraucht stets nur in abhngiger Weise verwendet wird . . .

Obwohl also das als Erstnomen fungierende Personalpronomen der icj-Reihe satzeinleitend verwendet wird und als proklitisch zu bezeichnen ist, kann es dennoch nicht wie

das Personalpronomen der jnA-Reihe am Anfang eines unabhngigen Satzes stehen".

I. M. Diakonoff, Semito-Hamitic Languages, Moscow 1965, 72; I. J. Gelb, Sequential

Reconstruction of Proto-Akkadian, Chicago 1969, Chap. 9.

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

Alexander S. Chetverukhiii

10

on the one hand, to a hypothetic lexeme with the meaning of "existence" and,

on the other hand, to a deictic base, both being presumably of the same origin,

cf. E A G 174.21 In addition, it is very likely that in Pr pers ind the morpheme nt

formerly had a relative pronoun function, so that the Egyptian paradigm might

be comparable with that of Ge'ez independent personal possessive pronouns formed after pattern "relative pronoun + personal suffix". The morph nt lies at

the base of the relative pronouns nt.j (m.) and nt(.j).t (f.), being also represented as "independent" demonstrative nt in ME N S nt piv . . . - G E G 190,2 ( " i t

is the fact that . . .") ; LGEC 616 ("c'est le fait que . . .").22

The main difference between the " I " and " I I . A " is in the character of the second constituent, both being absolutely comparable with the English "This/It ( = Y )

is X " and " H e ( = Y ) is X"it is worth remembering, that the Egyptian wordorder is, as a rule, the inverse of that in the Indo-European languages: Eg.

X Y = I.E. Y X . The 2 Pr pers is usually represented by Pr pers dep, though

the Pr pers ind is also possible as early as in OE: P T 703 b 701 : pwtw.t "You

are N " .

The scheme I I . is realized in the P T , although the jm'-variant is less frequent

as in the ME texts :

PI.

2. m.

2. f.

3. m.

3. f.

tw.t/nt.k +St s, q, ag

tm.tjnt.t + St s, q, ag

sw.tjnt.f+ St s, q, ag

st.tjnt.s + St s, q, ag

1. c.

jnn( + pw) = St s, q, ag

2. c.

nt.tn+ St s, q. ag

3. c.

ni.sn + St s, q, ag

St s can also be represented by word-combinations (groups), sometimes very

expanded, where a nuclear component (St s proper) is extended by different

kinds of attributes.23 The Pr pers ind often substitutes for 1 St s + pw. This is

evident from parallel texts in the P T and the texts-corrections : P T 1094 a, b ;

1097 a - c ; 1098a; 1161c etc. With pw: P T 703b 701: tw.t pw Pjpj "You are

P y o p e " ; P T 10&6a: sw.t pw Hr(w) ntr.w " T h e Horus of (the) gods is he", cf.

the old versions of P T 1066a and 1035bc, containing the patterns "jnk + nw

+ St ag". The nw-function here seems to be a double one: 1) as the formal logicgrammatical subject, and 2) as a substantivizer before St ag. I t is hard to say,

what function is the predominant one. In any case they seem to be less current

than those with pw.

The II.C is represented by still more seldom occurrences noted by M. Gilula2'1,

and can be demonstrated in the following way :

See also: . . IOjiaKHH, Pa3BHTHe CTpyKTypw npeaJiOHieHHH cbi3h c pa3BWTneM CTpynTypH MMCJiH, Moscow 1984, 116 and chap. 5; A . C. MeTBepyxHH, Pea:iH3amiH h cmhcji

KBaHTopa an3HCTeHUnajibH0CTH b CTpyKType ernneTCKoro npeJio>KeHHH (in print).

22 See also the following . H . Gardiner's articles: The Relative A d j e c t i v e ntj, in: Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology ( = P S B A ) 22 [1900], 37-42; Notes: (1)

jwtj and ntj. (2) The Demonstrative and its Derivatives, in : P S B A 22 [1900], 321-325.

23 Examples see in Callender's work and in K . Sethe, Der Noniinalsatz im gyptischen

und Koptischen, Leipzig 1916 ( = S N K ) , 59, 63, 68.

-' S. I . Groll, Non-Verbal Sentence Patterns in L a t e Egyptian, London 1967, e.g. p. 30

33 ( " T h e "ink B " pattern").

21

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

11

Old E g y p t i a n Nominal Sentence

1. c.

2. m.

2. f.

3. m.

3. f.

Sg.

Pl.

jnk(+pw) 4- any of the Pr pers

tw.tlnt.k + a,nv of the Pr pers

}m.tlt.t + any of the Pr pers

sw.tnLf + any of the Pr pers

st.tnt.s + any of the Pr pers

1. c.

2 C

" "

jnn( + t h e same)

,, .

,

<-<(+the same)

sw( + t h e

v

same)

The examples can be excerpted from ME on, mostly from the CT and the B D :

jnk pw sj st.t pw wj (CT.VII.157b-c) "She ( = "the Eye of Horus") is me, (and) I

am she" ; CT.IV.99h: jnk pw st.t pw tz phr "It is I/me, It is she, (and) vice versa",

i.e. "I am she, she is I(me)", or "I and sheit is just the same", quite analogous

to BD 64 (Nebseni) nt.f pw jnk pw tz phr "It is he, it is Ivice versa" = SNK

97, . 1. In ME Pr pers ind are used as the second constituent more readiliy than

Pr pers dep. Later patterns do not contain pw at all, see Gilula's article, p. 173:

jnk nt.k; jnk (m)nt(w).f; (m)nt.f (m)nt.k tz phr ; nt.f nt.ka, construction current

in Late Egyptian.

The material concerning N S with the Pr dem as the first constituent is attested much less. In PT there is an allusion to using forms of pronominal demonstrative series in -n (pn, tn, nn) as the first constituent in the pattern, comprising also a demonstrative in -w {pw, tw, nw), with both the intercoordination of

two Pr dem in gender and number, and the actualizing particle hm between

t h e m - P T 1643 c: SNK 89. To the end of OSE the demonstrative pi as the

first constituent was also possible, see Roeder, op. cit., p. 5253. The demonstrative pw as the first constituent was also possible in an interrogative NS, see

EAG 1010 ; GEG 497 ; LGEC 680.

It is plain that this function of pw is a secondary one, and, against E. Edel,

I.e., pw is not "ein offenbar auch sehr altes Fragewort" at all. A mechanism of

the phenomenon is quite elementary. The interrogative NS with initial pw is a

simple inversion of our schemes I and II : X pw. -*pw X?, X pw Y. -~pw X Y? The

inversion originally was used in constructing the totality (general, nexus) question, such a transformation being universal and trivial. The first position being

that of the rheme, pw bore the main logic-grammatical and semantical stress. It

is clear, that then the construction like "Is it X?" could convert into "What/

Who is X?", while "it" becomes an abstract indication. So, "Is it X ? " - "What

(kind of/for a(n)) X ? " - " W h a t / W h o is X?". Hence the example from EAG

1010: CT.II.290e: pw sw j'qj "Wer ist er, der da eintritt?" structurally reflects

an original "Ist es/das er, der da eintritt?". Here we have a notable instance of

transforming the nexus question (perhaps originating in its turn from that affirmative, or rhetorical "It is X, isn't it?") into the subjective one. Thus a converting of Pr dem into Pr interrogative can be traced. This phenomenon undoubtedly correlates to pw becoming formal in the affirmative NS, being expressed by

the loss of its agreement, see above.

Apart from the demonstratives in -w as the second constituent, the forms nn 25

25

A. C. HeTBepyxHH, OyHKUHH CTapoernneTCKHx yKaeaTejibHtix MecroHMeHHtt coieTHHH pw-p(w)-nn

Ha MaTepnane TeKCTOB nnpaMH^, 1 6 7 a, X V / I ( 2 ) ,

1981, 9 3 - 9 8 .

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

12

Alexander S. Cliet vcrukbin

and even n/i- c are also possible, see, e.g., PT 1616 a, 423c, 741c, 128a. The

internal ("inserted between") pw is also used here. The material being very sparse,

it would be of no use to make a special scheme. The following nevertheless should

be noted: The forms of Pr dem in -i and -n function as the first constituent; Pr

dem in -n, -w and -/ can be observed in the position of the second constituent.

Cf.EAG 187: PT 142c W: msj(.w) n.k pf, jwr(.w) n.k pn "geboren ist dir jener,

empfangen ist dir dieser", that can be treated as a N S (as the German Zustandspassiv, therewith the passage is translated by E. Edel). Here we have a case

marginal between nominal and verbal sentences (see also A. Yudakin's work,

our fn. 21). A suggestion imposes itself, that the least condition for making

such N S patterns was "not to bring together" two Pr dem of the same series,

i.e., simultaneously as the first and as the second constituent, the phenomenon

being perhaps a "language universal" through the very semantical value of

such a predicative construction, wherein "This is this" would be hardly expected in a real speech of two persons, cf. "Der ist das/es", "C'est cela/a" with

Egyptian pS pw (Roeder, op. cit., p. 52: pRhind 60 "Das ist es", and p. 45:

RecTrav 39,121: p i pw Wsjr "Der ist es, Osiris"). A disconnective function of

an actualizing particle is felt if we take PT 1643 c (tn hm tw . . .). B y the way,

the formal logic-grammatical subject pw in a trimembral NS acquires also, by

its very position, along of its main functions, a disconnective one somehow akin

to that of actualizing particles.

As it was previously demonstrated, it could be an indication of a tendency of

the logical stress strenghtening of the first constituent via putting in pw, if the

first constituent was represented only by one word-form.27 Pw, as far as it may be

observed, had, as a minimum, a triple function: at the logic-grammatical level of

syntactic analysis it was a formal logic-grammatical subject; at the semantic

level it often was an "equation-sign" ("one and the same as"); at the formal

structural level it functioned as a mere copula. Other possible approaches to

pw are in close dependence on what level (or sub-level) of syntactic analysis, or

what kind of theoretical method is chosen by the investigator, cf. e.g., Groll,

op. cit., passim, where she orientates herself to the rules of grammatical determination applied to Late Egyptian with its developed system thereof.

As to the Pr pers in the function of the first or second N S constituent, it is

obvious that without directly expressed dependence on the previous sentence,

the first position is always replaced by a Pr pers ind, not dep, see Barta's article

above. We have not come across the Pr pers dep as the first constituent of PT

N S , where its absence can be a result of a peculiar style dictated by the common

context. In any case, it was imposiible to say *wj pw, but only jnk pw "this/It is

I/me", the Pr pers ind acting usually as a logic-grammatical predicate, while

the Pr pers depas a logic-grammatical subject, never as predicate.

All the above remarks considered, let us proceed to our schemes. Now, if

SNK 88: Lebensmder 37: jx.t nj n(.j).t hn(j).t eine Sttte zum Niederlassen ist

jenes" nmlich des Jenseits . . . Die Stellung des Demonstrativums ist dieselbe wie

bei pw".

27 A. C. MeTBepyxHH, B3anMoaeficTBHe aormiecKoro yaapeHHH 3.> rpaMMaTHHecKoro noA.iewainero CTapoernneTCKOM npe^nowernni, TJpeBimft

cpeHeBeKOBti Boctok. MeropHH, ., Moscow 1983, 88105.

26

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

13

Old Egyptian Nominal Sentence

we take the common scheme I I in its full according to positional substitution,

Pr generalized on all the pronouns but pw, we get the following paradigm :

1. a. Pr ( + pu>) + Pr

b. Pr ( + pw) + St s

c. Pr ( + pw) + St ag

d. Pr ( + pw) + St q

2. a. St s (+pw) + Pr

b. St s ( + pw) + St s

c. St s ( + pw) + St ag

d. St s (+pu>) + St q

3. a. St ag (+jnc) + Pr

b. St ag ( + pw) -f St s

c. St ag ( +pw) + St ag

d. St ag ( +pw) + St q

4. a. St q (+pu;) + Pr

b. St q (+pu;) + St s

c. St q ( +pw) + St ag

d. St q (+pw;) + St q

We have already used this scheme. It was elaborated on the base of NS material in the PT, see our second article mentioned in fn. 11. It is worth repeating here the summing-up observations on a supply for every item of the scheme :

1. a: represented outside of the PT; 1. b2. d: represented in both realizations

(with and without pw) in and outside of the PT; 3. a: in the PT without pw;

3. b: in both realizations; 3.cd: lacking; 4.Lb: only without pw; 4.cd: lacking.

In the above article we analyzed mainly the pw presence/absence, and showed that this phenomenon, as well as the main function of pw, became evident

only due to the logic-grammatical method, the trimembral predicative constructions resulting as a rule from a superposition of two bimembral ones : 1 St s +

2 St s, ag, q, and 1 St s (ag, q) + 2 pw. Such a superposition is a linguistic frquentation irrespective of language typology, and, as to the NS, is irrelative

of presence and character of the copula in any given language. It is the lack of

real data for points 3.cd and 4.cd in the above scheme that aroused an impulse

to seek another way of studying the NS, putting aside for a while our logic-grammatical method, all the more since the constructions implied by the items in

question are very hard to be imagined in any real spoken language. The latter

makes it clear that the problem requires detailed theoretical linguistic discussion.

It seems likely that a new approach should be looked for somewhere at the

intersection of the "level of revealing some types of real sense relations between

the constituents of an utterance, based on using . . . a system of terms : a) a bearer of characteristics or its producer. . . and b) a denomination or designation

of characteristics . . . The second principal member of the utterance characterizes the bearer of a quality or producer of a characteristics . . ." 28 , and the "level

of analysis comprising . . . principal sentence membersthe subject and predicate" 29 . Regarding our problem, both levels appear to draw together at this

point, and just in defining the deep semantical structure, for it is here that "the

function of grammatical subject is always peculiar to a word with common meaning of presentivity (the "word" originating from the category of the substantive

or its pronominal equivalents) or a word occasionally "presentived" (substantiM. M. ryxMaH, II03HIJHH nojyiemamero naiiKax paannqHux: , in:

JioweHHH HBHKax pasjiHiHux , Leningrad 1972, 1935, eep. p. 21.

29 Ibid., p. 22.

28

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

npen-

14

Alexander S. C'liot verukhiii

vized) in any other way . . ." 3 0 . I t is precisely from this stand-point that the

functions of constituents were previously estimated by S . O . Kartsevsky and

A. de Groot 3 1 , the subject function being described as " a n absolutely attribute d " one. The following definition by N. D. Arutiunova is also proper hereto 3 -:

" T h e subject and predicate have different functions in the sentence: the subject

and other terms of presentive meaning substitute, in speech, for the real object,

which they have to identify for the communication addressee, i.e. act in their

denotative function, while the topic, aiming at communication formation, realizes only its significative (abstract, notional) contents, or sense . . . The rates of

word combinability in subject word-ordering are akin to regularities adjusting

the word junction with the help of predicative relation: in both cases the attributive adjunct is connected with the denotatum of a noun, not with its signific a t u m " . And, at last, the semantical correlation of the subject and predicate

contents in the O S E NS is quite in accordance with . I . Shutova's definitions 3 3 :

" . . . the subject denotes the item (object) about which some characteristics are

stated by the predicate. This is a general linguistic, universal, content of the

subject category in any language . . . The predicate is a principal member (constituent) signifying some characteristics stated in regard to the given item denoted

by the subject. (This is) a general linguistic, universal, content of the predicative

category as a bearer of characteristics . . . " .

Thus, such a general theoretical explanation of the subject (S) function as

that of an absolutely attributed, and of the predicate (P) function a a prepositional attributing, can best do for the paradigm above, especially in regard to

the absence of material on items 3.cd ; 4.cd. Hence we obtain a deep-semantical

definition of the sentence as an attributive syntagm, self-content for making (or

being perceived as) a separate communication-act. To be sure, predicative attributive relations are to be treated much wider than non-predicative-the fact

virtually underlined by A. de Groot and O. S. Kartsevsky critics (06mee h3hK 0 3 H a H H e , p. 329; Arutiunova, op. cit., p. 1113). Nevertheless, the non-predicative syntagm can be converted into the basis of that predicativethe fact quite

observable in the OE, be it NS, or the possessive conjugation forms. The multiformity of predicative attributive forms depends directly on grammatical

(first of allmorpho-syntactical) peculiarities of a languageranging from the

mere juxtaposition, set in a certain order, in a language of the isolating type, up

to the most complicated theoretically possible systems of co-ordination in a

language of that polysynthetic. B a c k to the O S E , here even an elementary survey

of data unequivocally reveals a close relation between the attributive and predicative syntagmata becoming then disconnected.

Here it is worth nothing that the semantical inversion could occur in a number of cases, e.g. in the sentence type with the constituent pw : the non-predicative attributing member changed into the predicative attributed constituentit is just the case with the scheme I : a non-predicative (for example, "this eye",

where " t h i s " is a non-predicative attribute) when used as a sentence, under30

31

32

33

. . CyHiiH, OGman Teopim 'lacTeii pe^H, Moscova- Leningrad, 1966, 9496.

Omee H3HK03naniie. BiiyrpeHHHH CTpyKTypa R3bii;a, Moscow 1972, 129.

H.

Apynonona, IIpej.iO/KeiiHe h ero cmhcji, Moscow 1 9 7 6 , 1 0 1 1 .

E. II. LLlyToua, Bonpocu Teopnw ciiUTaKCHCa, Moscow 1984, 120.

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

15

Old Egyptian Nominai Sentence

went transformation into "this (is an) eye", where "this (is)" is no more an

attribute, quite the reverse, "(an) eye", becomes a predicative attribute to

" t h i s " : "what's t h i s ? " , "what does this characterize?", the "characteristics"

being "(an) eye".

To the end of the OE, P r dem " t h i s " , in syntagm like "this eye", in predicative use (being converted into "this is an eye") disagreed in gender (and in

number) with the S t s, and therewith a formal difference between non-predicative

and predicative syntagmata was fixed, the Pr dem in -w in the masculine singular, namely pw, getting immutable in predicative use. An analogous "grammatical transmutation" from the non-predicative to the predicative syntagm should

be postulated for the forms of possessive conjugationsdm.f, sdm.n.f, etc., especially when "nomina actionis" are their basis 34 , something like "his hearing"

"he is (he's!) hearing". However, the transformation is not always indispensably

accompanied by semantical inversionas to our S paradigm, there is no inversion at points l.cd; 2.cd, though formal concord was also lost here.

In any case, on the level of deep semantics the problem of constituents' function a t points l . a and 2.b is probably unsolvable if the paradigm be taken as a

whole irrespective of every particular case. It is the way already gone by : trying to define functions of constituents at point 2.b, some authors paid their attention to the lexical meaning of constituents, the estimation and the comparison of constituental semantical extents, and to foundating a semantical classification of O S E N S S thereupon. This is a well-known approach, undoubtedly

justified and based on vast linguistic data. 3 5 The vulnerability of the method is

in inevitable subjectiveness while estimating the constituental semantic volume,

especially in operating with such pairs of the constituents, in which both of

them, the first constituent and the second one, express some abstract notions.

As concerns our O S E material the vulnerability grows to a large degree owing

to our ignorance in plenty of notions that came from antiquity, especially if

the material is borrowed of mortuary and religious texts, very rich in N S S . All

things considered, the semantic method's effectiveness conformably to the P T ,

CD and B D is reduced to its minimum.

Strange and inexplicable a discord may seem, namely that between 2.a, where

the subject occupies the end of N S , and 2.cd, where it takes the initial position.

Trying to solve the problem, we don't see any possibility other than to re-apply

to the logic-grammatical method, akin to related methods named as " a c t u a l

division of the sentence", "functional perspective of an utterance", "information-bearing structural analysis of the sentence", or "analysis of utterance into

theme and Theme"33, etc.

The universally recognized pioneer of the logical analysis application to Egyptian K u r t Sethe was, keeping in mind his famous " D e r Nominalsatz im gypW. Schenkel, Die altgyptische Suffixkonjugation, Wiesbaden 1975, passim.

See the work of Arutiunova above, fn. 32, and fn. 9.

3(1 Dictionary of Slavonic Linguistic Terminology, vol. 1, Prague 1977, 467; O. C. AxMaHOBa,

CjioBapb jnmrBHCTHHecKHX TepMiiHOB, Moscow 1969, 37; B. E . IIIeBHKOBa, CoepeMeHHUit

aHrilllflCKllii H3LJK. CjlOB, aKTyaJIbHOe HJieHeHHe, HHTOHaiJHH, Moscow 1980,

passim; . M. Co.iHijeB (pe.), H3tiK03HaHne. rpaMMaranecKoe h arayajibHoe HJieiieiiiie npeaJiOJKemm, Moscow 1984, passim, and the literature cited therein.

3/1

35

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

16

Alexander S. Chetverukhin

tischen und Koptischen" (Leipzig 1916) that has not up to now lost its significance, though the method has been continually improved by egyptologists engaged

with syntactic analysis, mostly in recent years, see the article beginning. The

method is not indeed devoid of cases of its own shortcomings, but from the logicgrammatical standpoint there is in no case a functional "lack of co-ordination"

at points generalized under 2, since the logic-grammatical predicate tends to

hold the initial position (l.bd; 2.a, cd; 3.ab; 4.ab) at least in the OE, that

was guaranteed also by use of pw&n "organizer" of a strict logic-grammatical

model allowing no redistribution of logic-grammatical functions between two

constituents. Only having taken for the starting-point Sethe's stands, one can

understand that Pr pers ind functions in OSE as logic-grammatical predicate

par excellence, while P r pers depas subject exclusively. This results also from

comparing such NSS as jnk pw, jnk pw tw, jnk pw tw.tjni.k (never *wj pw, etc.),

which are partly at hand, partly certainly reconstructable. The further investigation is impossible without proper taking in account the different role of actualizing particles and other means of the kind, the logical stress mobility, the

historical development of the logic-grammatical structure, and some other

related problems.

Now, if ever, it is totally impossible to give simple definitions of subject and

predicate at points l.a and 2.b, for "in the identity-sentence the subject and

the predicate can be defined to such extent, to which one of the constituents

represents something like temporal embodiment, or "presentative state", of an

object, and is formed, or may be formed, with predicative instrumental. In the

strict and proper sense of the term, the sentence of denotative identity, i.e. the

identity-sentence, is deprived of the subject and predicate, though it may be

divided in theme and rheme" (Arutiunova, op. cit., p. 325)of course, only the

spoken realization can fully satisfy the requirements of "the theme-rheme analysis". Only eligible context, or familiar situation with all the notions understandable, resp. the perfect knowledge of proper suprasegment means (intonations, peculiarities of logical stress, pauses)better all togethercan give assurance about the logic-grammatical division of such sentences as 2.b, if there

are no additional explicit ("infrasegment") markers of its logic-grammatical

structure like jr, jn and pw, or actualizing particles like js, etc. 37

The statement wouldn't be full, if we side-stepped the problem of structure in

a system of coincidence/divergence of logic-grammatical and deep-semantical

constituental positions in our praradigm. If one considers it able to accept the

logic-grammatical predicate in the OSE tending to stay in the initial position

(by the way, bot only in the NS), so in l.ad of the paradigm the positions of

semantic (deep-structural) S and diametrically diverge except for the doubtful l . a ; in 2.a they concure; in 2.b it is not clear; in 2.cd they diverge; in 3.ab

and 4.ab they coincide. It is the core of the phenomenon that is to be explained now. We have therefore two equivocal cases spoken above, five divergences

( ), and also five coincidences ( + ), i.e. an absolutely symmetrical system :

I)

l . b . P r ( + ^ ) + S t s ( - ) : 2.a. St a ( + w ) + P r ( + );

37

N o w we are just writing about some actualizing particles. See also A. Shisha-Halevy,

('l)rf in the Coffin Texts: Functional Tableu in: Journal of the American Oriental

Society 106 [1986], 641658. The (i)rf functions also on the logic-semantical level.

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

Old Egyptian Nominal Sentence

17

II)

I.e. Pr(+2M) + S t a g ( - ) : 3.a. St ag + 0 + P r

( + );

III)

l.d. Pr (+>u) + St q

( - ) : 4.a. St q + 0 + P r

( + );

IV)

2.C. St s (+pu7) + St ag ( - ) : 3.b. St ag (+jMf) + St s ( + );

V)

2.d. St s ( - f - ^ + St q ( - ) : 4.b. St q + 0 + S t s

( + )!

The final remark on pw: the scheme shows that if there is no divergency between the two levels, the use of pw is totally superfluous, but if the divergency is

regular, its use is quite possible. Such is the common tendency.

Clearly the system does show how the very Egyptian grammatical structure

(position + special morphology of personal pronouns) reflects the logical structure of the sentence, namely the presence of a special logic-grammatical structure, apparent not in form of "supersystem" (expressed exlusively by suprasegment means) but as "a subsystem within the system". This is not amazing

at all how things similar to the above system are represented in a lot of languages of the world. 38

Here it is worth saying about a frequently used term "focus", or "focussing",

having a very vague meaning, as it is noted by some authors 39 . We are under

the impression that this term means the result of a logical stress shift, and,

though not obligatory, structural changes provoked therewith, the volume of

the term ranging from a mere sense stress shift up to the full reorganization of

the syntactic structure under the influence of the context over the communication-act.

We would offer the following (structural-logic-semantical) definition: in all

cases where a divergency between the logic-grammatical and deep-semantical

positions of the constituents arises, no matter, be it a result of the context requirements or even speaker's will for the sake of expressiveness, if the divergency

leads to the full or partial rebuilding of the formal structure of the sentencethis

phenomenon should be called "focus", or "focussing". From this view-point

items l.bd; 2.c-d are "focussed", and 2.a; 3 . a - b ; 4.ab are "normal".

Summing-up note: Hereby we should underline the exclusive general theoretical significance of NS research. Its compactness and structural harmony permit to trace those structural features of the syntax which are not otherwise accessible. The NS study can also verify some suggestions previously made without considering the NS data. When studying the Egyptian NS, a great deal of

various data should be taken into account, some of them being quite "extralinguistic" ones. The more heterogeneous they are, the better.

38

B. 3. IIaH$njioB, BsaHMoneftcTBiie

39

Janet H.Johnson, "Focussing" on Various "Themes", in: Crossroad, p. 401410. Cf.

also C. J. Eyre, Approaches to the Analysis of Egyptain Syntax: Syntax and Pragmatics, ibid., p. 119143; Schenkel Fokussierung, passim.

H3HK21 H MHINJIEHUH, Moscow 1971, 219 CJI.; E. A. Kpett*

, HCCJIENOBAHHH H M a T e p a a J i t i no K>KarHpcKOMy H 3 t i K y , Leningrad 1982, 175ff.

Addendum to fn. 3

In: H B U K : JIHHTBHCTH^ecKne npojieMii coepeueHHott , Moscow 1988, qacn.

II, 3541.

Altorient. Forsch. 17 (1990) 1

Brought to you by | provisional account

Unauthenticated | 178.162.97.141

Download Date | 2/9/14 12:19 PM

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Frankfurter The Perlis of LoveДокумент22 страницыFrankfurter The Perlis of Lovesychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- MAKE or LET Exercises - Allowed ToДокумент8 страницMAKE or LET Exercises - Allowed Torosesaime23Оценок пока нет

- Adverbs WorksheetДокумент5 страницAdverbs Worksheetapi-300203854Оценок пока нет

- Contracts DefinitionsДокумент19 страницContracts DefinitionsAaron Smith100% (1)

- Cleopatra V Tryphæna and The Genealogy of The Later PtolemiesДокумент28 страницCleopatra V Tryphæna and The Genealogy of The Later Ptolemiessychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- Depuydt 2017 FuzzyДокумент21 страницаDepuydt 2017 Fuzzysychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- Lumie 'Re Et Cécité Dans L'Égypte Ancienne: Light and Blindness in Ancient EgyptДокумент18 страницLumie 'Re Et Cécité Dans L'Égypte Ancienne: Light and Blindness in Ancient EgyptAdnan BuljubašićОценок пока нет

- Taharqa in Western Asia and LibyaДокумент5 страницTaharqa in Western Asia and Libyasychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- Microbiological Analysis of A Mummy From The Archeological Museum in Zagreb PDFДокумент3 страницыMicrobiological Analysis of A Mummy From The Archeological Museum in Zagreb PDFsychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- Epigraphs in The Battle of Kadesh ReliefsДокумент19 страницEpigraphs in The Battle of Kadesh Reliefssychev_dmitry100% (1)

- Egyptian Pottery in Middle Bronze Age AshkelonДокумент9 страницEgyptian Pottery in Middle Bronze Age Ashkelonsychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- M. Korostovtsev, Notes On Late-Egyptian Punctuation. Vol.1, No. 2 (1969), 13-18.Документ6 страницM. Korostovtsev, Notes On Late-Egyptian Punctuation. Vol.1, No. 2 (1969), 13-18.sychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- Raphael Giveon, Egyptian Objects From Sinai in The Australian Museum. 2.3 (1974-75) 29-47Документ19 страницRaphael Giveon, Egyptian Objects From Sinai in The Australian Museum. 2.3 (1974-75) 29-47sychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- From Gulf To Delta in The Fourth Millennium Bce The Syrian ConnectionДокумент9 страницFrom Gulf To Delta in The Fourth Millennium Bce The Syrian Connectionsychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- Syrian Pottery From Middle Kingdom Egypt: Stage, Anticipation Set A FromДокумент9 страницSyrian Pottery From Middle Kingdom Egypt: Stage, Anticipation Set A Fromsychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- John MacDonald, Egyptian Interests in Western Asia To The End of The Middle Kingdom, An Evaluation. 1.5 (1972) 72-98.Документ27 страницJohn MacDonald, Egyptian Interests in Western Asia To The End of The Middle Kingdom, An Evaluation. 1.5 (1972) 72-98.sychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- A Fifth Dynasty Funerary Dress in The Petrie MuseumДокумент18 страницA Fifth Dynasty Funerary Dress in The Petrie Museumsychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- Amasis and LindosДокумент12 страницAmasis and Lindossychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- Apis Bull StelaeДокумент6 страницApis Bull Stelaesychev_dmitryОценок пока нет

- Ancient Egyptian Magic JansenДокумент12 страницAncient Egyptian Magic Jansensychev_dmitry100% (1)

- English Scheme of Work For Remove ClassДокумент8 страницEnglish Scheme of Work For Remove ClassmithzОценок пока нет

- Preposition Teaching PresentationДокумент20 страницPreposition Teaching Presentationyow jing pei100% (1)

- English GrammarДокумент16 страницEnglish GrammarAman SharmaОценок пока нет

- LEVIN. Main Verb Ellipsis in Spoken EnglishДокумент103 страницыLEVIN. Main Verb Ellipsis in Spoken EnglishfeaslpОценок пока нет

- What Is Functional Grammar?Документ13 страницWhat Is Functional Grammar?Pulkit Vasudha100% (1)

- 01 MorphologyДокумент52 страницы01 MorphologyGhina Verina LermanОценок пока нет

- Seminar 2 Intransitive PredicationsДокумент2 страницыSeminar 2 Intransitive PredicationsTeodora ButufeiОценок пока нет

- Japanese Time ExpressionДокумент5 страницJapanese Time Expressioners_chanОценок пока нет

- Adv PhraseДокумент2 страницыAdv Phrasewaqarali78692100% (1)

- Lesson 1: Be: Am, Are and Is Statement and Questions Contractions and Short AnswerДокумент11 страницLesson 1: Be: Am, Are and Is Statement and Questions Contractions and Short AnswerOvi KusumahОценок пока нет

- Parts of SpeechДокумент3 страницыParts of SpeechZobiaAzizОценок пока нет

- Tiger Times: Official Style/Grammar GuideДокумент5 страницTiger Times: Official Style/Grammar Guideapi-285711152Оценок пока нет

- Tugas HUKUM KONTRAK BISNIS INSTERNASIONALДокумент5 страницTugas HUKUM KONTRAK BISNIS INSTERNASIONALnovaaprianto253Оценок пока нет

- FCE GOLD Plus Teacher S BookДокумент3 страницыFCE GOLD Plus Teacher S BookAideen O'SullivanОценок пока нет

- Past Perfect Simple (Davno Prošlo Vreme)Документ3 страницыPast Perfect Simple (Davno Prošlo Vreme)ninanixОценок пока нет

- Sentence SequencingДокумент3 страницыSentence SequencingHafiza ZainonОценок пока нет

- Agreement and PredicateДокумент11 страницAgreement and PredicatePufyk RalukОценок пока нет

- Futsal FUTSAL: HistoryДокумент3 страницыFutsal FUTSAL: Historyamora eliОценок пока нет

- Student's Name: - DateДокумент3 страницыStudent's Name: - DateAbiGómezОценок пока нет

- Verbe Neregulate GermanaДокумент12 страницVerbe Neregulate GermanaGabriela DiaconuОценок пока нет

- Transformational GrammarДокумент5 страницTransformational GrammarCarey AntipuestoОценок пока нет

- Expressed or Implied Contracts: Contract LawДокумент5 страницExpressed or Implied Contracts: Contract LawTyОценок пока нет

- Sentences PDFДокумент16 страницSentences PDFmaurolivares0% (1)

- Notes On AdverbsДокумент16 страницNotes On AdverbsMinaChangОценок пока нет

- Spanish Verb WheelsДокумент19 страницSpanish Verb WheelsArmando CruzОценок пока нет

- MODUL KD 8-NewДокумент11 страницMODUL KD 8-NewFuad Punya Percetakan100% (1)

- Simple Future Story 2Документ7 страницSimple Future Story 2Vera Markova100% (1)