Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

David Gelernter What Do Murderers Deserve

Загружено:

anon_9800769390 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

295 просмотров3 страницыThe document discusses the death penalty and why communities execute murderers. It argues that execution is meant to proclaim that murder is intolerable and defiles the community. By executing murderers, the community is forced to take on the burden of moral certainty and make an absolute statement that murder is evil and will be punished. However, the author acknowledges that America is divided on the issue and has become cavalier about murder, executing murderers inconsistently and without moral certainty. The death penalty should not be abandoned, even if imperfectly applied, as it represents a necessary response to deliberate murder in a community.

Исходное описание:

wf

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOC, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документThe document discusses the death penalty and why communities execute murderers. It argues that execution is meant to proclaim that murder is intolerable and defiles the community. By executing murderers, the community is forced to take on the burden of moral certainty and make an absolute statement that murder is evil and will be punished. However, the author acknowledges that America is divided on the issue and has become cavalier about murder, executing murderers inconsistently and without moral certainty. The death penalty should not be abandoned, even if imperfectly applied, as it represents a necessary response to deliberate murder in a community.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOC, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

295 просмотров3 страницыDavid Gelernter What Do Murderers Deserve

Загружено:

anon_980076939The document discusses the death penalty and why communities execute murderers. It argues that execution is meant to proclaim that murder is intolerable and defiles the community. By executing murderers, the community is forced to take on the burden of moral certainty and make an absolute statement that murder is evil and will be punished. However, the author acknowledges that America is divided on the issue and has become cavalier about murder, executing murderers inconsistently and without moral certainty. The death penalty should not be abandoned, even if imperfectly applied, as it represents a necessary response to deliberate murder in a community.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOC, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 3

http://www.gallup.com/poll/1606/death-penalty.

aspx

What Do Murderers Deserve?

David Gelernter

A Texas woman, Karla Faye Tucker, murdered two people with a pickax, was

said to have repented in prison, and was put to death. A Montana man,

Theodore Kaczynski, murdered three people with mail bombs, did not repent,

and struck a bargain with the Justice Department: He pleaded guilty and will

not be executed. (He also attempted to murder others and succeeded in

wounding some, myself included.) Why did we execute the penitent and

spare the impenitent? However we answer this question, we surely have a

duty to ask it.

And we ask itI do, anywaywith a sinking feeling, because in modern

America, moral upside-downness is a specialty of the house. To eliminate

race prejudice we discriminate by race. We promote the cultural assimilation

of immigrant children by denying them schooling in English. We throw honest

citizens in jail for child abuse, relying on testimony so phony any child could

see through it. We make a point of admiring manly women and womanly

men. None of which has anything to do with capital punishment directly, but

it all obliges us to approach any question about morality in modern America

in the larger context of this country's desperate confusion about elementary

distinctions.

Why execute murderers? To deter? To avenge? Supporters of the death

penalty often give the first answer, opponents the second. But neither can be

the whole truth. If our main goal were deterring crime, we would insist on

public executionswhich are not on the political agenda, and not an item

that many Americans are interested in promoting. If our main goal were

vengeance, we would allow the grieving parties to decide the murderer's

fate; if the victim had no family or friends to feel vengeful on his behalf, we

would call the whole thing off.

In fact, we execute murderers in order to make a communal proclamation:

that murder is intolerable. A deliberate murderer embodies evil so terrible

that it defiles the community. Thus the late social philosopher Robert Nisbet

wrote: Until a catharsis has been effected through trial, through the finding

of guilt and then punishment, the community is anxious, fearful,

apprehensive, and, above all, contaminated.

When a murder takes place, the community is obliged to clear its throat and

step up to the microphone. Every murder demands a communal response.

Among possible responses, the death penalty is uniquely powerful because it

is permanent. An execution forces the community to assume forever the

burden of moral certainty; it is a form of absolute speech that allows no

waffling or equivocation.

Of course, we could make the same point less emphatically, by locking up

murderers for life. The question then becomes: Is the death penalty

overdoing it?

The answer might be yes if we were a community in which murder was a

shocking anomaly. But we are not. One can guesstimate, writes the

criminologist and political scientist John J. DiIulio Jr., that we are nearing or

may already have passed the day when 500,000 murderers, convicted and

undetected, are living in American society.

DiIulio's statistics show an approach to murder so casual as to be depraved.

Our natural bent in the face of murder is not to avenge the crime but to

shrug it off, except in those rare cases when our own near and dear are

involved.

This is an old story. Cain murders Abel, and is brought in for questioning:

Where is Abel, your brother? The suspect's response: What am I, my

brother's keeper? It is one of the first human statements in the Bible; voiced

here by a deeply interested party, it nonetheless expresses a powerful and

universal inclination. Why mess in other people's problems?

Murder in primitive societies called for a private settling of scores. The

community as a whole stayed out of it. For murder to count, as it does in the

Bible, as a crime not merely against one man but against the whole

community and against God is a moral triumph still basic to our integrity,

and it should never be taken for granted. By executing murderers, the

community reaffirms this moral understanding and restates the truth that

absolute evil exists and must be punished.

On the whole, we are doing a disgracefully bad job of administering the

death penalty. We are divided and confused: The community at large

strongly favors capital punishment; the cultural elite is strongly against it.

Consequently, our attempts to speak with assurance as a community sounds

like a man fighting off a chokehold as he talks. But a community as cavalier

about murder as we are has no right to back down. The fact that we are

botching things does not entitle us to give up.

Opponents of capital punishment describe it as a surrender to emotionsto

grief, rage, fear, blood lust. For most supporters of the death penalty, this is

false. Even when we resolve in principle to go ahead, we have to steel

ourselves. Many of us would find it hard to kill a dog, much less a man.

Endorsing capital punishment means not that we yield to our emotions but

that we overcome them. If we favor executing murderers, it is not because

we want to but because, however much we do not want to, we consider

ourselves obliged to.

Many Americans no longer feel that obligation; we have urged one another to

switch off our moral faculties: Don't be judgmental! Many of us are no

longer sure evil even exists. The cultural elite oppose executions not (I think)

because they abhor killing more than others do, but because the death

penalty represents moral certainty, and doubt is the black-lung disease of

the intelligentsiaan occupational hazard now inflicted on the whole culture.

Returning then to the penitent woman and the impenitent man: The Karla

Faye Tucker case is the harder of the two. We are told that she repented. If

that is true, we would still have had no business forgiving her, or forgiving

any murderer. As theologian Dennis Prager has written apropos this case,

only the victim is entitled to forgive, and the victim is silent. But showing

mercy to penitents is part of our religious tradition, and I cannot imagine

renouncing it categorically.

I would consider myself morally obligated to think long and hard before

executing a penitent. But a true penitent would have to have renounced (as

Karla Faye Tucker did) all legal attempts to overturn the original conviction. If

every legal avenue has been tried and has failed, the penitence window is

closed.

As for Kaczynski, the prosecutors say they got the best outcome they could,

under the circumstances, and I believe them. But I also regard this failure to

execute a cold-blooded, impenitent terrorist and murderer as a tragic

abdication of moral responsibility. The community was called on to speak

unambiguously. It flubbed its lines, shrugged its shoulders, and walked away.

In executing murderers, we declare that deliberate murder is absolutely evil

and absolutely intolerable. This is a painfully difficult proclamation for a selfdoubting community to make. But we dare not stop trying. Communities in

which capital punishment is no longer the necessary response to deliberate

murder may exist. America today is not one of them.

David Gelernter is the author, most recently, of Machine Beauty (Basic

Books, 1998). From Commentary (April 1998). Subscriptions: $45/yr. (12

issues) from the American Jewish Committee, 165 E. 56th St., New York, NY

10022.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Death Penalty Must Be AbolishedДокумент4 страницыThe Death Penalty Must Be AbolishedHannah Elizabeth-Alena GomesОценок пока нет

- Koch, E (2013) Death and Justice, in Current Issues and Enduring Questions, 10th Edition, S Barnet & D Bedau, EdsДокумент5 страницKoch, E (2013) Death and Justice, in Current Issues and Enduring Questions, 10th Edition, S Barnet & D Bedau, EdsJoey YanОценок пока нет

- PRISM Sep Oct 11 FinalДокумент52 страницыPRISM Sep Oct 11 FinalHooman HedayatiОценок пока нет

- Philo Death PenaltyДокумент1 страницаPhilo Death PenaltyJai Illana LoronoОценок пока нет

- "Tolerance Is Not Always Good," Foster Friess's Speech To 6th Annual Becket Foundation DinnerДокумент6 страниц"Tolerance Is Not Always Good," Foster Friess's Speech To 6th Annual Becket Foundation Dinnermredden1Оценок пока нет

- An End to Murder: A Criminologist's View of Violence Throughout HistoryОт EverandAn End to Murder: A Criminologist's View of Violence Throughout HistoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (6)

- Amber YoungДокумент4 страницыAmber YoungtommyjranieriОценок пока нет

- Dershowitz on Killing: How the Law Decides Who Shall Live and Who Shall DieОт EverandDershowitz on Killing: How the Law Decides Who Shall Live and Who Shall DieОценок пока нет

- Quotes - Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, JRДокумент4 страницыQuotes - Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, JRA.J. MacDonald, Jr.Оценок пока нет

- Bloodthirsty Bitches and Pious Pimps of Power: The Rise and Risks of the New Conservative Hate CultureОт EverandBloodthirsty Bitches and Pious Pimps of Power: The Rise and Risks of the New Conservative Hate CultureРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (9)

- Of Suicide: The Moral ProblemДокумент37 страницOf Suicide: The Moral ProblemWagner RodriguesОценок пока нет

- Privileged Victims: How America’s Culture Fascists Hijacked the Country and Elevated Its Worst PeopleОт EverandPrivileged Victims: How America’s Culture Fascists Hijacked the Country and Elevated Its Worst PeopleОценок пока нет

- Thecast Newsletter Issue 6Документ5 страницThecast Newsletter Issue 6Machiavelli DavisОценок пока нет

- Death Penalty OppositionДокумент1 страницаDeath Penalty OppositionSunny ValeОценок пока нет

- The Ripper's Children: Inside the World of Modern Serial KillersОт EverandThe Ripper's Children: Inside the World of Modern Serial KillersОценок пока нет

- IeppaperДокумент6 страницIeppaperapi-301902337Оценок пока нет

- It's Okay To Let Go: Why It's Time For Blacks To Walk Away From ChristianityОт EverandIt's Okay To Let Go: Why It's Time For Blacks To Walk Away From ChristianityРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- LifewatchДокумент8 страницLifewatchSwiss WissОценок пока нет

- Death PenaltyДокумент10 страницDeath PenaltyRon Jovaneil JimenezОценок пока нет

- No Legal Defense: Contemporary Accounts of Mississippi Lynchings 1835 - 1964От EverandNo Legal Defense: Contemporary Accounts of Mississippi Lynchings 1835 - 1964Оценок пока нет

- Dissertation Capital PunishmentДокумент6 страницDissertation Capital PunishmentWhereToBuyCollegePapersSingapore100% (1)

- May I Kill?: Just War, Non-Violence, and Civilian Self-DefenseОт EverandMay I Kill?: Just War, Non-Violence, and Civilian Self-DefenseОценок пока нет

- Warren Black Nihilism The Politics of Hope READДокумент36 страницWarren Black Nihilism The Politics of Hope READtristoineОценок пока нет

- The Tree of Good and Evil: Or, Violence by the Law and against the LawОт EverandThe Tree of Good and Evil: Or, Violence by the Law and against the LawОценок пока нет

- Skin and BloodДокумент140 страницSkin and BloodMichaelОценок пока нет

- Terror in the Name of God: Why Religious Militants KillОт EverandTerror in the Name of God: Why Religious Militants KillРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (38)

- DBQ - CRM 2012Документ7 страницDBQ - CRM 2012Tony YoungОценок пока нет

- With Death Penalty, Let Punishment Truly Fit The Crime: by Robert Blecker, Special To CNNДокумент3 страницыWith Death Penalty, Let Punishment Truly Fit The Crime: by Robert Blecker, Special To CNNMuhamad Ruzaidi M YunusОценок пока нет

- 11 - Media, Et Al and That Illusive Commodity Called TheДокумент16 страниц11 - Media, Et Al and That Illusive Commodity Called TheHistoryBuff2004Оценок пока нет

- The Satan Model: Exposing the Link Between Serial Crime and SatanОт EverandThe Satan Model: Exposing the Link Between Serial Crime and SatanОценок пока нет

- The Road To Auschwitz Wasn't Paved With Indifference-1347Документ9 страницThe Road To Auschwitz Wasn't Paved With Indifference-1347Sheikh SaqibОценок пока нет

- Murder On The Mind: A Review On Murder, The Psychology and Criminal DefenseОт EverandMurder On The Mind: A Review On Murder, The Psychology and Criminal DefenseОценок пока нет

- The Meaning of The Rittenhouse Verdict in AmericaДокумент5 страницThe Meaning of The Rittenhouse Verdict in AmericasiesmannОценок пока нет

- Talking with Psychopaths: Mass Murderers and Spree KillersОт EverandTalking with Psychopaths: Mass Murderers and Spree KillersОценок пока нет

- Cherith Brook CW Advent 2014Документ12 страницCherith Brook CW Advent 2014Cherith Brook Catholic WorkerОценок пока нет

- We Gon' Be Alright: Notes on Race and ResegregationОт EverandWe Gon' Be Alright: Notes on Race and ResegregationРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (34)

- Dangerous Spaces: Violent Resistance, Self-Defense, & Insurrectional Struggle Against GenderДокумент24 страницыDangerous Spaces: Violent Resistance, Self-Defense, & Insurrectional Struggle Against Genderpineal-eyeОценок пока нет

- Secrets Can Be Murder: What America's Most Sensational Crimes Tell Us About OurselvesОт EverandSecrets Can Be Murder: What America's Most Sensational Crimes Tell Us About OurselvesРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (10)

- What Is Kings Thesis in Letter From Birmingham JailДокумент7 страницWhat Is Kings Thesis in Letter From Birmingham Jailaprilfordsavannah100% (2)

- Black Nihilism - Wake 2016Документ208 страницBlack Nihilism - Wake 2016JohnBoalsОценок пока нет

- Crime Inc.: How Democrats Employ Mafia and Gangster Tactics to Gain and Hold PowerОт EverandCrime Inc.: How Democrats Employ Mafia and Gangster Tactics to Gain and Hold PowerРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (3)

- Jesus Christ As A Human Rights Violation Victim and A Human Rights AdvocateДокумент2 страницыJesus Christ As A Human Rights Violation Victim and A Human Rights AdvocateCheryl L. Daytec-YangotОценок пока нет

- I Have A Dream: AdvertisementДокумент3 страницыI Have A Dream: Advertisementsawaay0% (1)

- Supernatural Serial Killers: Chilling Cases of Paranormal Bloodlust and Deranged FantasyОт EverandSupernatural Serial Killers: Chilling Cases of Paranormal Bloodlust and Deranged FantasyРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (3)

- Death Penalty Discussion TopicДокумент10 страницDeath Penalty Discussion TopicJonathon Frame100% (2)

- Death Penalty (C)Документ7 страницDeath Penalty (C)Victor VenidaОценок пока нет

- Death Penalty in The PhilippinesДокумент2 страницыDeath Penalty in The PhilippinesPearl Joy MijaresОценок пока нет

- Charles U3 ArrgumemtativeДокумент5 страницCharles U3 ArrgumemtativeWillary CharlesОценок пока нет

- The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning' - The New York TimesДокумент10 страницThe Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning' - The New York TimesAnonymous FHCJucОценок пока нет

- Sonnet 39 ArticleДокумент2 страницыSonnet 39 ArticlelalyitaОценок пока нет

- Distosia BahuДокумент185 страницDistosia BahuAdith Fileanugraha100% (1)

- Daily Lesson Log in Math 9Документ13 страницDaily Lesson Log in Math 9Marjohn PalmesОценок пока нет

- Indian Standard: General Technical Delivery Requirements FOR Steel and Steel ProductsДокумент17 страницIndian Standard: General Technical Delivery Requirements FOR Steel and Steel ProductsPermeshwara Nand Bhatt100% (1)

- Dharnish ReportДокумент13 страницDharnish Reportdarshan75% (4)

- Voloxal TabletsДокумент9 страницVoloxal Tabletselcapitano vegetaОценок пока нет

- Target The Right MarketДокумент11 страницTarget The Right MarketJoanne100% (1)

- TC1 Response To A Live Employer Brief: Module Code: BSOM084Документ16 страницTC1 Response To A Live Employer Brief: Module Code: BSOM084syeda maryemОценок пока нет

- 434-Article Text-2946-1-10-20201113Документ9 страниц434-Article Text-2946-1-10-20201113Rian Armansyah ManggeОценок пока нет

- Definition of Diplomatic AgentДокумент3 страницыDefinition of Diplomatic AgentAdv Faisal AwaisОценок пока нет

- Manual Watchdog 1200 PDFДокумент30 страницManual Watchdog 1200 PDFdanielОценок пока нет

- Thomas Friedman - The World Is FlatДокумент12 страницThomas Friedman - The World Is FlatElena ȚăpeanОценок пока нет

- Arts 9 M1 Q3 1Документ15 страницArts 9 M1 Q3 1Gina GalvezОценок пока нет

- Notes Ilw1501 Introduction To LawДокумент11 страницNotes Ilw1501 Introduction To Lawunderstand ingОценок пока нет

- Sampling TechДокумент5 страницSampling TechJAMZ VIBESОценок пока нет

- Reading Exercise 2Документ2 страницыReading Exercise 2Park Hanna100% (1)

- Bareilly Ki Barfi Full Movie DownloadДокумент3 страницыBareilly Ki Barfi Full Movie Downloadjobair100% (3)

- Ijel - Mickey's Christmas Carol A Derivation That IДокумент6 страницIjel - Mickey's Christmas Carol A Derivation That ITJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Debt Policy and Firm Performance of Family Firms The Impact of Economic AdversityДокумент21 страницаDebt Policy and Firm Performance of Family Firms The Impact of Economic AdversityMiguel Hernandes JuniorОценок пока нет

- Aol2 M6.1Документ5 страницAol2 M6.1John Roland CruzОценок пока нет

- Minipro Anemia Kelompok 1Документ62 страницыMinipro Anemia Kelompok 1Vicia GloriaОценок пока нет

- Transparency IIДокумент25 страницTransparency IIKatyanne ToppingОценок пока нет

- Alex - Level B Case 2Документ1 страницаAlex - Level B Case 2Veronica Alvarez-GallosoОценок пока нет

- E-Fim OTNM2000 Element Management System Operation GuideДокумент614 страницE-Fim OTNM2000 Element Management System Operation GuidePrabin Mali86% (7)

- CatalysisДокумент50 страницCatalysisnagendra_rdОценок пока нет

- DD McqsДокумент21 страницаDD McqsSyeda MunazzaОценок пока нет

- Statistics and Image Processing Part 2Документ42 страницыStatistics and Image Processing Part 2Sufiyan N-YoОценок пока нет

- Manila Trading & Supply Co. v. Manila Trading Labor Assn (1953)Документ2 страницыManila Trading & Supply Co. v. Manila Trading Labor Assn (1953)Zan BillonesОценок пока нет

- Azhari, Journal 7 2011Документ11 страницAzhari, Journal 7 2011Khoirunnisa AОценок пока нет

- 0 - Past Simple TenseДокумент84 страницы0 - Past Simple Tenseשחר וולפסוןОценок пока нет

- The Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartОт EverandThe Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleОт EverandSomething Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (34)

- The War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionОт EverandThe War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- Decolonizing Therapy: Oppression, Historical Trauma, and Politicizing Your PracticeОт EverandDecolonizing Therapy: Oppression, Historical Trauma, and Politicizing Your PracticeОценок пока нет

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesОт EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (70)

- When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaОт EverandWhen and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (33)

- Be a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooОт EverandBe a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,От EverandBound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (69)

- The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row (Oprah's Book Club Summer 2018 Selection)От EverandThe Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row (Oprah's Book Club Summer 2018 Selection)Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (232)

- The Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave TradeОт EverandThe Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave TradeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (3)

- Say It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyОт EverandSay It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (18)

- Say It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyОт EverandSay It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyОценок пока нет

- America's Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered EverythingОт EverandAmerica's Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered EverythingРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (21)

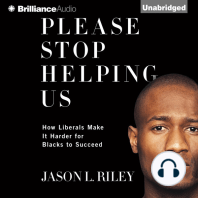

- Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to SucceedОт EverandPlease Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to SucceedРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (155)