Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Crucible Modern Thought L9c

Загружено:

hawku0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

3 просмотров3 страницыCrucible Modern Thought Lesson 9c

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

TXT, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документCrucible Modern Thought Lesson 9c

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате TXT, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

3 просмотров3 страницыCrucible Modern Thought L9c

Загружено:

hawkuCrucible Modern Thought Lesson 9c

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате TXT, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 3

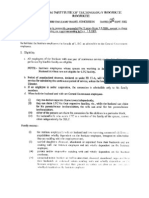

Locke

John Locke was an English philosopher who lived a.d. 1632

1704. He was the founder of the modern school of philosophy

known as Empiricism, the principal doctrine of which is that all

knowledge or truth, is to be obtained only through experience, as

opposed to the theory of innate ideas. Locke developed the

Baconian idea that experience was the true source of knowledge,

and that general truths should be reasoned inductively from

observed facts of experience. He held that in empirical facts

we may find the only source of knowledge, since the mind

has no innate ideas. His teaching was that the materials for

thought and reason are impressed upon the mind from outside,

and that the sole activity of the mind is that of linking and

combining together the ideas so obtained. He argued from this

that our knowledge of the external world, resting, as it does,

upon sense-perception; must be merely upon the plane of

probability. He, however, violated his fundamental principle

by assuming a rationalistic ideal including the assertion that

we have an intuitive knowledge of the existence of the self,

the existence of God, and of mathematical and moral truths.

While under the influence of Bacon, he was nevertheless largely

influenced by the rationalism of Descartes. While apparently

advancing the full doctrine of empiricism, he managed to point

out the way for its reconciliation with rationalism, which way

was pursued by Kant in after years.

Hume

David Hume, a Scotch philosopher (a.d. 1711 1776), afterward

carried Locke s fundamental theories to their logical conclusion,

and held that there was naught knowable other than conscious

experiences; that is, impressions and their reflection, ideas.

Hume held that we cannot transcend this knowledge, although

The Crucible of Modern Thought

116

we may combine the ideas by association, etc., according to the

established principles of psychology. Hume taught that we

cannot prove the existence of God, of self, or of matter all of

which ideas are the illusions of imagination, having no basis in

actual experience. He carried empiricism to the realm of pure

skepticism.

Berkeley

George Berkeley was a bishop of the Church of England, who

lived a.d. 1685 1753. He was the founder of the modern school

of Idealism, which system he developed largely upon the basis

of Locke, Descartes, Spinoza and Leibnitz. He held that matter

cannot be conceived to actually exist, the only real substance

being mind; and that the material world is nothing but a

complex of mental impressions which appear and disappear

in accordance with established laws of nature. He held that

the reality of sense objects consisted in their being perceived,

and that the assumption of an object apart from its idea is

fallacious. He denied the individual existence of object apart

from the subjective idea of it, and of both subject and object

apart from the mind of God, or the Absolute. He held that,

there being no real external world, the phenomena of sense

must depend upon God continually, necessitating perception.

Berkeley set out to prove the existence of God by his idealistic

theory, but reasoned in a circle when he assumed the existence

of God to make his theory tenable. His opponents endeavored

to confute him by the familiar illustration of one kicking a stone

and realizing the reality of the effect produced, but he and his

followers logically explained that the said effect was merely a

sensation known by the mind, and not a thing outside of the

mind. Idealism, in various forms, has permeated many later

philosophical systems. Fichte, Schelling and Hegel have made

the doctrine parts of their respective systems, and it is heard

from in the metaphysical systems and theories of to-day.

Western Philosophies.

117

Kant

Immanuel Kant, the great German philosopher, lived a.d.

1724 1804. His work created a new era in modern philosophy,

and has profoundly affected all subsequent philosophical

thought, even in systems which are apparently opposed to his

fundamental principles. He was the founder of the modern

school of Critical Philosophy. He, following the skepticism of

Hume as to the idea of causality, enunciated the proposition

that the faculty of knowledge, and the sources of knowledge,

must be critically examined before anything could be definitely

determined regarding objective truth. He aimed to separate

the intuitive, or a priori mental forms, from those obtained

empirically, or through experience; and also to define and

determine the limits of human reason and the knowledge

obtained therefrom. He attributed to the faculties of sense,

understanding, judgment and reason, certain innate ideas,

intuitive truths, or a priori forms, which must be valid and real

because of their necessity, as, for instance, the ideas of time

and space, cause and effect, action and reaction, reality, unity,

the idea of the Absolute, and certain moral truths, such as his

famous categorical imperative which held as axiomatic the

idea that one should Act only on that maxim whereby thou

canst at the same time will that it should become a universal

law the latter being claimed by him to be a moral law which

admits of no condition or exception.

He held that theoretical knowledge was limited, inasmuch as

the universal ideas existing in the mind would yield knowledge

only when excited thereto by the presentation of their

corresponding objects in actual experience, and that even then

what we really know is not the thing-in-itself, but merely the

thing-as-it-appears the phenomenon, not the noumenon.

The result of his reasoning is that certain things-in-themselves

must be unknowable, as they can never appear to the mind

as objects of actual experience in consciousness, and are to be

thought of only as belonging to the noumenal, or the world

The Crucible of Modern Thought

118

of things-in-themselves. These unknowable things are the

transcendental thought-postulates in psychology, cosmology,

and theology, as, for instance, God, freedom, and immortality

of the soul, and the opposites or contradictions which

reason meets in considering the ideas of infinity, as infinite

time, infinite space, infinite chain of cause and effect. As an

authority says of Kant s teachings: His point is that though it is

unquestionably necessary to be convinced of God s existence, it

is not so necessary to demonstrate it. He shows that all such

demonstrations are scientifically impossible and worthless. On

the great questions of metaphysics immortality, freedom,

God scientific knowledge is hopeless.

It will be seen that Kant ambitiously essayed to harmonize

and blend the opposing principles of rationalism and

empiricism of a priori and a posteriori knowledge of innate

ideas and ideas arising from experience. He held that knowledge

is composed of two factors, as follows: (1) A priori, innate in

the mind itself, antedating experience and necessary to make

experience possible; and (2) a posteriori, coming from without,

as the raw material of sensation, through experience. He held

that the a priori knowledge is not usable without the material

of sense experience; and that the a posteriori knowledge would

fail to take form in consciousness were it not for the mold ideas

innately existing in the mind. He held, therefore, that while

theoretical reason or scientific inquiry is necessarily limited

to the realm of experience and phenomenon, still practical

reason is valid in postulating belief in the moral law and order,

and belief in the existence of a world of transcendental reality;

Practical reason, he held, made it necessary for us to postulate

the existence of God, freedom, and immortality, and to

manifest our belief in our moral life, although pure reason

was absolutely unable to demonstrate their existence. Thus did

Kant endeavor to build a structure of faith upon a foundation

of reason.

Western Philosophies.

119

Вам также может понравиться

- Suggestion 24Документ2 страницыSuggestion 24hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L20Документ1 страницаSuggestion L20hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L17Документ1 страницаSuggestion L17hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L16Документ1 страницаSuggestion L16hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L8Документ1 страницаSuggestion L8hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggest L13Документ2 страницыSuggest L13hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion 11Документ2 страницыSuggestion 11hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L17Документ1 страницаSuggestion L17hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L17Документ1 страницаSuggestion L17hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L15Документ2 страницыSuggestion L15hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L9Документ1 страницаSuggestion L9hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L6Документ2 страницыSuggestion L6hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggest L14Документ1 страницаSuggest L14hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L10Документ1 страницаSuggestion L10hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L12Документ1 страницаSuggestion L12hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L 4Документ1 страницаSuggestion L 4hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L2Документ1 страницаSuggestion L2hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L5Документ1 страницаSuggestion L5hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L3Документ1 страницаSuggestion L3hawkuОценок пока нет

- The Will L77Документ1 страницаThe Will L77hawkuОценок пока нет

- The Will L78Документ1 страницаThe Will L78hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L2Документ1 страницаSuggestion L2hawkuОценок пока нет

- The Will L77Документ1 страницаThe Will L77hawkuОценок пока нет

- Suggestion L1Документ2 страницыSuggestion L1hawkuОценок пока нет

- The Will L73Документ1 страницаThe Will L73hawkuОценок пока нет

- The Will 74Документ1 страницаThe Will 74hawkuОценок пока нет

- The Will 76Документ1 страницаThe Will 76hawkuОценок пока нет

- The Will L75Документ1 страницаThe Will L75hawkuОценок пока нет

- The Will 66Документ1 страницаThe Will 66hawkuОценок пока нет

- The Will 70Документ1 страницаThe Will 70hawkuОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5783)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Leave Travel Concession PDFДокумент7 страницLeave Travel Concession PDFMagesssОценок пока нет

- Political Science Assignment Sem v-1Документ4 страницыPolitical Science Assignment Sem v-1Aayush SinhaОценок пока нет

- Self Concept's Role in Buying BehaviorДокумент6 страницSelf Concept's Role in Buying BehaviorMadhavi GundabattulaОценок пока нет

- Invitation to Kids Camp in Sta. Maria, BulacanДокумент2 страницыInvitation to Kids Camp in Sta. Maria, BulacanLeuan Javighn BucadОценок пока нет

- Recent Course CompactДокумент2 страницыRecent Course Compactprecious omokhaiyeОценок пока нет

- Regional Director: Command GroupДокумент3 страницыRegional Director: Command GroupMae Anthonette B. CachoОценок пока нет

- Apgenco 2012 DetailsOfDocuments24032012Документ1 страницаApgenco 2012 DetailsOfDocuments24032012Veera ChaitanyaОценок пока нет

- Quiz (14) Criteria For JudgingДокумент4 страницыQuiz (14) Criteria For JudgingJemmy PrempehОценок пока нет

- The 5000 Year Leap Study Guide-THE MIRACLE THAT CHANGED THE WORLDДокумент25 страницThe 5000 Year Leap Study Guide-THE MIRACLE THAT CHANGED THE WORLDMichele Austin100% (5)

- Ar2022 en wb1Документ3 страницыAr2022 en wb1peach sehuneeОценок пока нет

- Instant Download Statistics For Business and Economics Revised 12th Edition Anderson Test Bank PDF Full ChapterДокумент32 страницыInstant Download Statistics For Business and Economics Revised 12th Edition Anderson Test Bank PDF Full Chapteralicenhan5bzm2z100% (3)

- James Tucker - Teaching Resume 1Документ3 страницыJames Tucker - Teaching Resume 1api-723079887Оценок пока нет

- Philippines-Expanded Social Assistance ProjectДокумент2 страницыPhilippines-Expanded Social Assistance ProjectCarlos O. TulaliОценок пока нет

- 2023 Whole Bible Reading PlanДокумент2 страницы2023 Whole Bible Reading PlanDenmark BulanОценок пока нет

- Risk Register 2012Документ2 страницыRisk Register 2012Abid SiddIquiОценок пока нет

- The Swordfish Islands The Dark of Hot Springs Island (Updated)Документ200 страницThe Swordfish Islands The Dark of Hot Springs Island (Updated)Edward H71% (7)

- Location - : Manhattan, NyДокумент15 страницLocation - : Manhattan, NyMageshwarОценок пока нет

- EXIDEIND Stock AnalysisДокумент9 страницEXIDEIND Stock AnalysisAadith RamanОценок пока нет

- O&M Manager Seeks New Career OpportunityДокумент7 страницO&M Manager Seeks New Career Opportunitybruno devinckОценок пока нет

- HDFC BankДокумент6 страницHDFC BankGhanshyam SahОценок пока нет

- Joyce Flickinger Self Assessment GuidanceДокумент5 страницJoyce Flickinger Self Assessment Guidanceapi-548033745Оценок пока нет

- Impact of Information Technology On The Supply Chain Function of E-BusinessesДокумент33 страницыImpact of Information Technology On The Supply Chain Function of E-BusinessesAbs HimelОценок пока нет

- Anders LassenДокумент12 страницAnders LassenClaus Jørgen PetersenОценок пока нет

- Show Me My Destiny LadderДокумент1 страницаShow Me My Destiny LadderBenjamin Afrane NkansahОценок пока нет

- Swami Sivananda NewsletterДокумент50 страницSwami Sivananda NewsletterNaveen rajОценок пока нет

- 2020 BMW Group SVR 2019 EnglischДокумент142 страницы2020 BMW Group SVR 2019 EnglischMuse ManiaОценок пока нет

- UKG Monthly SyllabusДокумент4 страницыUKG Monthly Syllabusenglish1234Оценок пока нет

- City of Baguio vs. NiñoДокумент11 страницCity of Baguio vs. NiñoFD BalitaОценок пока нет

- Psac/Sait Well Testing Training ProgramДокумент1 страницаPsac/Sait Well Testing Training Programtidjani73Оценок пока нет

- Literary Structure and Theology in The Book of RuthДокумент8 страницLiterary Structure and Theology in The Book of RuthDavid SalazarОценок пока нет