Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

14th Finance Commission

Загружено:

Vijaya VijayaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

14th Finance Commission

Загружено:

Vijaya VijayaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A watershed 14th Finance Commission

It is clear that the far-reaching recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission, along with the creation of NITI Aayog, will radically

alter Centre-state fiscal relations, write Syed Zubair Naqvi, Kapil Patidar and Arvind Subramanian

of GDP. Moreover, nearly all the state

governments have enacted fiscal

responsibility legislations (FRLs), which

requires them to observe high standards

of fiscal discipline such as keeping the

deficit low.

Further, as part of the new Centrestate fiscal relations, for example, under

the NITI Aayog, mechanisms for peer

assessments and mutual accountability could be created, and incentives

could be provided for maintaining fiscal discipline. This is becoming routine

practice in many federal structures

where sovereignty is shared between

the members. The FFC recommendations and the consequences they entail

offer an opportune time for instituting

such mechanisms.

he report of the Fourteenth

Finance Commission (FFC) was

tabled in Parliament yesterday.

The government has accepted its farreaching, indeed radical, recommendations that have the potential to redefine Indian federalism in a long overdue

and desirable manner. This piece

describes the key recommendations

and highlights some of their major

implications. It is based on updating

assumptions in the FFC report, which is

the only source of data used in the numbers presented below. The discussion

below, especially the estimates, should

be seen as illustrative at best.

Vertical and horizontal devolution

The FFC has increased the amount that

the Centre has to transfer to the states

from the divisible pool of taxes by 10

percentage points, from 32 per cent to 42

per cent. Its radical nature is indicated

by the comparison with the previous

two Finance Commissions (FCs) that

increased the share going to the states

by 1 and 1.5 percentage points, respectively. So, the FFC recommendations

represent a ten and six-and-a-half fold

increase, respectively relative to the previous two FCs. Had the new share been

implemented in 2014-15 (Budget estimates), the Centres fiscal resources

would have shrunk by about 1.20 lakh

crore (0.9 per cent of gross domestic

product or GDP). If the comparison were

to be in terms of overall (tax plus nonplan grants) devolution, the increase

would be roughly comparable to that in

tax devolution.

In addition, the FFC has significantly changed the sharing of resources

between the states what is called horizontal devolution. The FFC has proposed a new formula (see table:

Horizontal Devolution...) for the distribution of the divisible tax pool among

the states. There are changes both in

the variables included/excluded as well

as the weights assigned to them.

Relative to the Thirteenth Finance

Commission, the FFC has incorporated

two new variables: 2011 population and

forest cover; and excluded the fiscal discipline variable.

Several other types of transfers have

been proposed, including grants to

rural and urban local bodies, a performance grant, and grants for disaster

relief and reducing the revenue deficit

of eleven states. These transfers total

approximately 5.3 lakh crore for the

period 2015-20.

Uniformly large addition to

states resources

The impact of FFC transfers to the states

needs to be assessed in two ways: gross

and net FFC transfers will clearly add

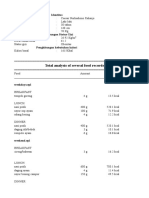

HORIZONTAL DEVOLUTION FORMULA IN

THE 13TH AND 14TH FINANCE COMMISSIONS

Variable

Population (1971)

Population (2011)

Fiscal capacity/Income distance

Area

Forest cover

Fiscal discipline

Total

FFC TRANSFER PER CAPITA AND

NSDP PER CAPITA

Weights accorded

13th

14th

25.0

17.5

0.0

10.0

47.5

50.0

10.0

15.0

0.0

7.5

17.5

0.0

100

100

Log FFC transfer per capita

Source: Reports of 13th and 14th Finance Commission

to the resources of all the states in

absolute terms and substantially. They

will also increase resources when scaled

by states population, net state domestic

product, or own tax revenues, with the

latter connoting the addition to fiscal

spending power.

Implementing the FFC recommendations alone would undermine the

centres fiscal position substantially. The

philosophy of the FFC report is that

there should be some corresponding

reduction in the central assistance to

states (CAS, the so-called plan transfers). Thus, greater fiscal autonomy to

the states would be achieved both on

the revenue side (on account of states

now having more resources and more

untied resources) and on the expenditure side because of reduced CAS transfers. The exact mechanism for implementation will be discussed in the

months ahead but the legally backed

schemes as well as flagship schemes

that meet core objectives, such as rural

livelihoods and poverty alleviation, will

be, and need to be, preserved.

The net impact on the states will

depend not just on the transfers effected via the FFC, but also the consequen-

tial alteration of CAS. Under some simple assumptions about how the latter

will be distributed, we find that all states

will end up better off than before,

although there will be some variation

amongst the states.

Increase in progressivity

of overall transfers

The FFC transfers have a more

favourable impact on the states that

are relatively less developed, which is

an indication that they are progressive,

that is, states with lower per capita net

state domestic product (NSDP) are likely to receive on average much larger

transfers per capita . The correlation

between per capita NSDP and FFC

transfers per capita is -0.72 based on

some broad assumptions about FFC

transfers. (see chart: FFC transfer...)

This indicates that the FFC recommendations do go in the direction of

equalising the income and fiscal disparities between the major states.

In contrast, CAS transfers are only

mildly progressive: the correlation coefficient with state per capita GDP (over

the last three years) is -0.29. This is a

consequence of plan transfers moving

away from being formula-based (GadgilMukherjee formula) to being more discretionary in the last few years. Greater

central discretion evidently reduced

progressivity.

A corollary is that implementing the

FFC recommendations would help

address inter-state resource inequality:

progressive tax transfers would increase,

while discretionary and less progressive

plan transfers would decline.

Weakening fiscal discipline?

Will FFC transfers lead to less fiscal discipline? There are two reasons to be optimistic. First, in the last few years the

overall deficit of the states has been

about half of that of the Centre: in 201415 (Budget estimates) for example, the

combined fiscal deficit of the states was

estimated at 2.4 per cent of GDP compared to 4.1 per cent for the Centre. So,

on average, states, if anything, are more

disciplined than the Centre.

Based on analysing recent state

finances, we find that additional transfers toward the states as a result of the

FFC will improve the overall fiscal

deficit of the combined central and state

governments by about 0.3-0.4 per cent

Conclusions

With the caveats noted earlier, the main

conclusions are that the FFC has made

far-reaching changes in tax devolution

that will move the country toward

greater fiscal federalism, conferring

more fiscal autonomy on the states. This

will be enhanced by the FFC-induced

imperative of having to reduce the scale

of other central transfers to the states. In

other words, states will now have greater

autonomy both on the revenue and

expenditure fronts.

This, of course, is in addition to

the benefits that will accrue from

addressing all the governance and

incentive problems that have arisen

from programmes being dictated and

managed by the distant central government rather than by the proximate

state governments.

To be sure, there will be transitional challenges, notably how the Centre

will meet its multiple objectives given

the shrunken fiscal envelope. But there

will be offsetting benefits: moving from

CAS to FFC transfers will increase the

overall progressivity of resource transfers to the states. Another is that overall public finances might actually

improve by more than suggested by

looking at the central government

finances alone.

In sum, it is clear that the far-reaching recommendations of the FFC,

along with the creation of the NITI

Aayog, will radically alter Centre-state

fiscal relations, and further the governments vision of cooperative and

competitive federalism.

The necessary, indeed vital, encompassing of cities and other local bodies

within the embrace of this new federalism is the next policy challenge, a

change that we would like to see.

The authors are assistant directors and

chief economic advisor respectively, in the

Ministry of Finance

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- ECO-321 Development Economics: Instructor Name: Syeda Nida RazaДокумент10 страницECO-321 Development Economics: Instructor Name: Syeda Nida RazaLaiba MalikОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Education - Khóa học IELTS 0đ Unit 3 - IELTS FighterДокумент19 страницEducation - Khóa học IELTS 0đ Unit 3 - IELTS FighterAnna TaoОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Dryden, 1994Документ17 страницDryden, 1994Merve KurunОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- 15-Statutory Report Statutory Define Law (Legal Protection) Statutory MeetingДокумент2 страницы15-Statutory Report Statutory Define Law (Legal Protection) Statutory MeetingRaima DollОценок пока нет

- 01 Mono Channel BurnerДокумент1 страница01 Mono Channel BurnerSelwyn MunatsiОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- LAB ActivityДокумент2 страницыLAB ActivityNicole AquinoОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Interactive and Comprehensive Database For Environmental Effect Data For PharmaceuticalsДокумент5 страницInteractive and Comprehensive Database For Environmental Effect Data For PharmaceuticalsRaluca RatiuОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Aphids and Ants, Mutualistic Species, Share A Mariner Element With An Unusual Location On Aphid Chromosomes - PMCДокумент2 страницыAphids and Ants, Mutualistic Species, Share A Mariner Element With An Unusual Location On Aphid Chromosomes - PMC2aliciast7Оценок пока нет

- Gulayan Sa Barangay OrdinanceДокумент2 страницыGulayan Sa Barangay OrdinancekonsinoyeОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Cdd161304-Manual Craftsman LT 1500Документ40 страницCdd161304-Manual Craftsman LT 1500franklin antonio RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Information Technology Solutions: ADMET Testing SystemsДокумент2 страницыInformation Technology Solutions: ADMET Testing Systemskrishgen biosystemsОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Good Laboratory Practice GLP Compliance Monitoring ProgrammeДокумент17 страницGood Laboratory Practice GLP Compliance Monitoring ProgrammeamgranadosvОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- CHEM F313: Instrumental Methods of Analysis: Flame Photometry & Atomic Absorption SpectrosДокумент26 страницCHEM F313: Instrumental Methods of Analysis: Flame Photometry & Atomic Absorption SpectrosHARSHVARDHAN KHATRIОценок пока нет

- Vulnerability of The Urban EnvironmentДокумент11 страницVulnerability of The Urban EnvironmentKin LeeОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Interview Questionaries (Cont.)Документ27 страницInterview Questionaries (Cont.)shubha christopherОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Soduim Prescription in The Prevention of Intradialytic HypotensionДокумент10 страницSoduim Prescription in The Prevention of Intradialytic HypotensionTalala tililiОценок пока нет

- R. Raghunandanan - 6Документ48 страницR. Raghunandanan - 6fitrohtin hidayatiОценок пока нет

- Monitor Zoncare - PM-8000 ServicemanualДокумент83 страницыMonitor Zoncare - PM-8000 Servicemanualwilmer100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Tugas Gizi Caesar Nurhadiono RДокумент2 страницыTugas Gizi Caesar Nurhadiono RCaesar 'nche' NurhadionoОценок пока нет

- Fermentation Media: Agustin Krisna WardaniДокумент27 страницFermentation Media: Agustin Krisna WardaniYosiaОценок пока нет

- Calamansi: Soil and Climatic RequirementsДокумент4 страницыCalamansi: Soil and Climatic Requirementshikage0100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Report On Marketing of ArecanutДокумент22 страницыReport On Marketing of ArecanutsivakkmОценок пока нет

- הרצאה- אנמיה וטרומבוציטופניהДокумент87 страницהרצאה- אנמיה וטרומבוציטופניהliatfurmanОценок пока нет

- Articulo de Las 3 Tesis Por BrowДокумент30 страницArticulo de Las 3 Tesis Por BrowJHIMI DEIVIS QUISPE ROQUEОценок пока нет

- TG Chap. 10Документ7 страницTG Chap. 10Gissele AbolucionОценок пока нет

- Accomplishment Report Rle Oct.Документ7 страницAccomplishment Report Rle Oct.krull243Оценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- CITEC Genesis & GenXДокумент45 страницCITEC Genesis & GenXPutra LangitОценок пока нет

- Oral PresentationДокумент4 страницыOral PresentationYaddie32Оценок пока нет

- Daikin Sky Air (RZQS-DV1) Outdoor Technical Data BookДокумент29 страницDaikin Sky Air (RZQS-DV1) Outdoor Technical Data Bookreinsc100% (1)

- Broza Saric Kundalic - Ethnobotanical Study On Medicinal +Документ16 страницBroza Saric Kundalic - Ethnobotanical Study On Medicinal +turdunfloranОценок пока нет