Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The State of Film and Media Feminism

Загружено:

Ceiça FerreiraАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The State of Film and Media Feminism

Загружено:

Ceiça FerreiraАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The State of Film and Media Feminism

Author(s): AnnetteKuhn

Source: Signs, Vol. 30, No. 1, Beyond the Gaze: Recent Approaches to Film

Feminisms<break></break>Special Issue Editors<break></break>Kathleen McHugh and Vivian

Sobchack (Autumn 2004), pp. 1221-000

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/422233 .

Accessed: 22/08/2015 09:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 193.137.168.1 on Sat, 22 Aug 2015 09:48:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Annette Kuhn

The State of Film and Media Feminism

rom the mid-1970s until around 1990, I was actively involved in film

feminism. Although not a career academic for most of that period,

I was doing a lot of teaching and writing and, for several years during

the 1980s, conducting doctoral research in the social history of cinema.

I got into feminist film studies in the first place because I was a cinephile

and a student of film. I was (and am) also a feminist, and there was a

period when it seemed politically urgent to bring these commitments and

enthusiasms togetherin ones work and practice. That moment has, I

think, passedto a degree because many of the battles have been won.

But in different ways and to various degrees that moment has been formative of the disciplines of film and media studies, shaping their content

and conduct as well as the habits of thought of those of all genders and

generations who work in those fields.

This change of consciousness goes beyond the academy, too: themes

and motifs in films that might thirty years ago have seemed commonplace

or gone unremarked (women in peril, say) are treatable on screen today,

if at all, only ironically or in some other distanced manner. If we choose

to be optimistic about the impact of our work, we may conclude that this

is a measure of the consciousness-raising potential of scholarship and

teaching. At the same time, if the political energy that brought about

these changes is still there, it seems to require less proclamation. So if in

my own work feminism is still a sine qua non, it seems less necessary, less

urgent, to say so. It is built in, can be taken for granted.

Cinema and film remain my main areas of interest, and I am aware that

these have changed in all sorts of ways since I first got involved in film

studies. Nonetheless, the seductiveness of new media notwithstanding,

I think it would be unwise to lose sight of the idea of film as a distinctive

medium. Of course the nature of films distinctiveness does not stay constantthis is something to be charted and explored. Film studies is a

different discipline from what it was in the 1970s (and media studies

scarcely existed then), and here I would like to explore three areas in

which both disciplines seem to me to be evolving and to look at the issues

[Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2004, vol. 30, no. 1]

2004 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 0097-9740/2004/3001-0013$10.00

This content downloaded from 193.137.168.1 on Sat, 22 Aug 2015 09:48:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1222

Kuhn

around feminism in each of them. If I focus my discussion largely on film

and cinema, this is not just because these are the areas with which I am

most familiar but also because I think there are significant issues of media

specificity here, and I want to avoid conflating different media. The three

areas are: the ontology, aesthetics, and metapsychology of film; cultural

studies of cinema (and other media); and social histories of cinema (and

other media). I shall concentrate mainly on the first and offer some brief

concluding remarks on the other two.

The ontology, aesthetics, and metapsychology of film

There is a distinction to be made straight away between film and cinema.

I use the term film to refer to the distinctive textual features of the medium.

By cinema I mean the entire industry or apparatus of cinema, that is, film

texts along with the contexts and manner in which they are produced and

consumed.

Inspired by the novelty of this very modern medium, the earliest

theorists of film were keen to pinpoint what was different and distinctive

about it and thus directed their inquiries at the ontology, the essential

nature, of film and also at films aesthetics (see, e.g., Balazs 1970). Later

theorists expanded ontological concerns into metapsychological studies

explorations of the distinctiveness of films address to its spectators, of the

relationship between the film text and the subjectivity of the spectator

(Metz 1982). Are we at risk now of losing sight of the aesthetic and

metapsychological distinctiveness of filmeven if this is very different

today from what it might have been in the mediums earlier years?

The task of theory is to illuminate its objects, and vice versa. Film

theory should help us make sense of film, and films ought to be the

grounding and the inspiration for film theory. In an essay from the late

1980s on the then-current state of feminist film theory, I wrote that

theories of film do not translate automatically to other media (Kuhn

1989). This, I think, is still true. We need to take the objects, not the

theory, as the starting point for our thinking and allow ourselves to learn

from them in all their specificity, whether they be film, television, video,

or whatever else. This is one reason why the idea of applying theory

makes me uneasy: it feels rather a constraining, procrustean sort of exercise

and rarely produces convincing or helpful results.

We are asked to consider whether psychoanalytic theory still has anything to offer feminist inquiry into the media. Psychoanalysis was used

first of all in relation to film (as opposed to other media), and as I see it

feminist psychoanalytic film theory sprang from two rather different de-

This content downloaded from 193.137.168.1 on Sat, 22 Aug 2015 09:48:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S I G N S

Autumn 2004

1223

sires: to understand the nature of film, in particular its metapsychology,

in relation to sexual difference; and to understand how gender informs

the contents of films and/or how men and women relate to film and/or

cinema.

These desires come together in thinking on how psychoanalytic ideas

on the production of sexual difference may contribute to a more general

understanding of the interaction between films and those who watch them.

In practice, however, they pull in opposing directions. The central preoccupations of the first do not readily map onto gender or other identity

politics, in part because of the polymorphous range of subjectivities in the

internal world. Feminine subjectivity is not the same as femaleness, and

male subjectivity is not the same as maleness, and in the psyche many

more subjectivities even than these are potentially available. More importantly, perhaps, psychoanalysis is as much, or more, concerned with

the internal world of the psyche as it is with the external world of politics

and social action. It is not that these worlds are separate and unrelated

so far as psychoanalysis is concerned. Rather, they are different from each

other, and it is the job of psychoanalysis to explore and explain their

interrelation in particular cases rather than to assume it. The second desire

springs from a more overtly political debate about women (or men) as

they appear in films and/or constitute an audience for them. For the sake

of brevity, I shall call the two tendencies, respectively, psychoanalytic

and social.

Not surprisingly, these two tendencies constantly seem to anger or

disappoint each other. For many feminists, the psychoanalytic tendency

seems abstruse and unrelated to the real world, a judgment scarcely

mitigated by the difficulty of some of the writing in this area. Many have

felt excluded from this debate, and such feelings generate resentment

along with lack of understanding. Even those like myself who find psychoanalytic theory enormously helpful in thinking about film (and indeed

about culture more generally) can struggle with this. As well, at a certain

period, happily now past, a demand for compliance seemed to be in the

air, especially around acceptance of the work of Jacques Lacan. This is

the very sort of thing that makes people feel inadequate, and I certainly

still have difficulty finding some of Lacans work, particularly that around

sexual difference, convincing. At the same time, I do not believe that this

absolves me from trying to come to grips with it, and colleagues whose

work I greatly respect have successfully done this and produced excellent

feminist exegeses ofand challenges toLacan. The best of this work

sheds light on the connections and the differences between Lacan and

Sigmund Freud on the one hand and existential phenomenology on the

This content downloaded from 193.137.168.1 on Sat, 22 Aug 2015 09:48:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1224

Kuhn

other. Where it is linked with the metapsychological study of film, this

work is particularly helpful and should be required reading for all students

of film (Rose 1986).

From the standpoint of psychoanalytic theory the social tendency

generates the demand that psychoanalysis explain phenomena that are

beyond its scope. For example, psychoanalysis does not claim to deal with

social aspects of gender and other social differences such as those of race

and class. The very fact that we are asked to review the continuing

relevance of psychoanalysis to the study of film (and other media) suggests

that these differences remain unfinished business. This has made for a

fraught encounter between feminist politics on the one hand and psychoanalytic film theory on the other. An immediate consequence of this

is that at a certain point the two tendencies parted company and set off

in quite different directions, without really acknowledging that a separation had taken place. The social strand inspired various kinds of cultural study of cinema and other media (on which more later), while the

psychoanalytic tendency fed into various feminist-inspired metapsychologies of film, including theories of the masquerade, fantasy, and masochism (Doane 1982; Cowie 1984; Studlar 1984).

So what, if any, is the relevance of feminist psychoanalytic film theory

today? My first response to this question is to say that if I were working in

cultural studies of cinema (or other media), psychoanalysis would not be

my first port of conceptual or methodological call. In this area other approaches (such as cultural ethnography and audience research) have proven

more productive. If psychoanalysis does offer any continuing relevance to

understanding film (if not necessarily to understanding other media), it will

be in a circumscribed arena, accompanied by the recognition that psychoanalysis cannot explain everything. It will also be with objectives that are

not powered first and foremost by feminism tout court. That is, we might

consider setting aside a totalizing feminist desire (I do not, of course,

suggest that such a desire should be abandoned) and not being shy about

concentrating on film as distinct from cinema and from other media. With

these caveats in mind, I believe that psychoanalysis has a lot to offer film

theory, in particular the metapsychology of cinema, in terms of depth of

understanding and inspiration for further inquiry.

Cinepsychoanalysis has concerned itself largely with the psychical

organization of looking and seeing, drawing on the psychoanalytic

account of human development: it is for good reason that the subject of

cinema is invariably called a spectator. This emphasis on vision calls up

Freuds thinking on the drives and their activity in creating differences of

social gender out of psychical sexual difference. We should remember that

This content downloaded from 193.137.168.1 on Sat, 22 Aug 2015 09:48:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S I G N S

Autumn 2004

1225

for Freud, one of the key processes at work here is repression, and therefore

the Unconscious. To this extent, in Freudian terms, sexual-libido drives,

including the drive to pleasurable looking (scopophilia), partake in the

production of the Unconscious and have a central unconscious component. This is transported into and elaborated on in Lacans thinking. To

this extent, psychoanalytic theories of film spectatorship have rested on

both the centrality of vision and the activity of the Unconscious, and these

concerns have been carried over into feminist psychoanalytic film theory

in work on the gaze. While, as I shall suggest, psychoanalytic theories

of the gaze can be seen as rather limiting, there is much work still to be

done in this area. In particular, the key question in Christian Metzs

seminal essay The Imaginary Signifier (in what way can psychoanalysis

cast light on the cinematic signifier? [1982, 25]) has still not been satisfactorily answered.

This project was more or less abandoned in anglophone film theory,

largely because Metzs work is not only gender blind (which would not

necessarily make it untenable) but is also (unacceptably) dismissive of the

sexual difference agenda informing the Freudian concepts on which it

otherwise productively draws. To cite just one example, Metz rightly

points to the role of disavowal (I know this is not so, but I accept the

illusion for the time being) in organizing spectatorial belief and pleasure

in film, arguing that to this extent the cinematic signifier is a fetish

and/or that the spectator-film relationship is psychically analogous to that

between the fetishist and his object. At the same time, though, Metz

contrives to disregard Freuds main point about fetishism, which is that

it arises from the disavowal of sexual difference (Freud 1977). It is possible

that, as far as the metapsychology of film is concerned, the disavowal is

more important than the sexual difference: we are not after all bound to

the letter of Freud. But such a hypothesis calls for inquiry and argument.

What I am suggesting is that prefeminist psychoanalytic film theory,

or film theory that does not prioritize issues of sexual difference, has been

prematurely abandoned, and that psychoanalytic metapsychologies of film

that do not take sexual difference as their starting point might be just as

worthy of exploration as those that do. For the latter, feminist readings

of Freud and Lacan have led the way in that for both Freud and Lacan

the key arena of sexual difference is the Oedipal moment, when the infant

recognizes the mothers lack. However, while most feminist psychoanalytic film theory has followed this lead, a number of writers, feminist

and otherwise, have argued for the significance of the pre-Oedipal in

understanding the spectator-film relationship (Baudry 1974; Studlar

1984). Nonetheless, to the best of my knowledge, psychoanalytic work

This content downloaded from 193.137.168.1 on Sat, 22 Aug 2015 09:48:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1226

Kuhn

on early objects and how they get woven into the subjects experience of

its world has yet to be thoroughly explored in relation to film as an object

that inhabits both our inner and our outer worlds (Winnicott 1971; Konigsberg 1996). This area, for one, could be significant to the extent that

it addresses at least two of the objections raised against psychoanalytic

film theory.

It has become commonplace to observe that psychoanalytic film

theorys emphasis on vision in the film-spectator encounter is partial, and

that spectatorial engagements have beenand with certain kinds of cinema, such as IMAX, remainmore fully embodied than the idea of the

gaze would suggest (Gunning 1986; Bukatman 1999). In addition to this,

I would argue that the emphasis on the Unconscious in psychoanalytic

film theory has resulted in a downplaying of the activity of partly or fully

conscious aspects of the spectators inner world in the encounter. That

is, the spectators experience, considered in psychoanalytic terms, might

also be usefully addressed (Kuhn 1989, 2003).

In conclusion, then, I believe that, as a system of ideas that can illuminate film and in particular add to our understanding of what is at stake in

the encounter between films and spectators, psychoanalysis has much to

offer film theory. To the extent that psychoanalysis can shed light on the

question of how sexual difference organizes this encounter, film scholars

who are also interested in questions of a broadly feminist nature will

undoubtedly continue to follow or contribute to this rather specialized

debate. However, I believe that the key agenda for psychoanalytic film

theory lies elsewhere.

Cultural studies of cinema (and other media)

Psychoanalysis is unlikely to prove useful to feminists who are interested

in cinema (as opposed to film), by which I mean those seeking to interrogate cinema for its engagements with women, sexual difference, sexual/

gender identity, or sexual politics. Many of those who approach cinema

from this angle do so from a base in disciplines other than film studies

media studies, cultural studies, and womens studies, for example, as well

as more traditional disciplines like English, history, or sociologyand so

may well be uninterested in the ontology, aesthetics, or metapsychology

of film. In cultural studies of cinema, films or cinema are studied not in

their own right but as they engage external issues: race, gender, violence,

and so on. By extension, media other than cinema are readily assimilable

This content downloaded from 193.137.168.1 on Sat, 22 Aug 2015 09:48:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S I G N S

Autumn 2004

1227

to this approach. Regardless of the medium, in cultural studies the time

frame tends to be the present, the media contemporary.

Terms like reflection and representation characterize work that inquires

into the relationship between media content (and occasionally formal

organization) on the one hand and a range of social issues on the other.

Cultural studies of media may also include inquiries into the consumption

and uses of media. Because inquiry in these areas can appear deceptively

straightforward until you try to do it properly, work in cultural studies of

media can vary enormously in quality. Research methodologies in cultural

studies are on the whole underdeveloped, and where they are not (as in

certain types of audience research and media ethnography) research design

can be complicated and the conduct of a good-quality investigation expensive and time consuming, often yielding disappointingly superficial

findings. However, as long as there are media, and feminists interested in

media, the demand for feminist cultural studies of media will remain. We

owe it to the discipline and to our students to enhance methodological

skills and awareness in this area.

Social histories of cinema (and other media)

While there is potential for overlap between cultural studies and social

histories of media, in that cultural studies methods may be brought to

bear on historical media and their uses, in practice they remain effectively

separate areas of inquiry. Unlike cultural studies, social histories of media

have the benefit of established methodological protocols. As far as cinema

is concerned, certainly, sources and methods of research are well documented, and film studies scholars have been pursuing innovative and distinctive lines of historical inquiry since the 1970s (Allen and Gomery 1985).

At the same time, there is still work to be done in feminist, as in other,

social histories of the media, and excellent examples have been set in

particular by some U.S. feminist scholars with backgrounds in film studies

(see, e.g., Hansen 1991; Staiger 1995). Key areas of feminist inquiry

include the history of womens contribution to the making of films and

the history of womens activities as consumers of films, and the scope for

new research in these fields is clearly potentially international. As far as

feminist-informed work in film and media studies worldwide is concerned,

this, in my view, is where to seek the cutting edge today.

Institute for Cultural Research

Lancaster University

This content downloaded from 193.137.168.1 on Sat, 22 Aug 2015 09:48:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1228

Kuhn

References

Allen, Robert C., and Douglas Gomery. 1985. Film History: Theory and Practice.

New York: Knopf.

Balazs, Bela. 1970. Theory of the Film: Character and Growth of a New Art. Trans.

Edith Bone. New York: Dover.

Baudry, Jean-Louis. 1974. Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus. Trans. Alan Williams. Film Quarterly 28(2):3947.

Bukatman, Scott. 1999. The Artificial Infinite: On Special Effects and the Sublime. In Alien Zone II: The Spaces of Science-Fiction Cinema, ed. Annette Kuhn,

24975. London: Verso.

Cowie, Elizabeth. 1984. Fantasia. m/f 9:71104.

Doane, Mary Ann. 1982. Film and Masquerade: Theorising the Female Spectator. Screen 23(34):7487.

Freud, Sigmund. 1977. Fetishism. In his On Sexuality: Three Essays on the Theory

of Sexuality and Other Works, ed. and trans. James Strachey, 35157. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Gunning, Tom. 1986. The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and

the Avant Garde. Wide Angle 8(34):6370.

Hansen, Miriam. 1991. Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Konigsberg, Ira. 1996. Transitional Phenomena, Transitional Space: Creativity

and Spectatorship in Film. Psychoanalytic Review 83(6):86589.

Kuhn, Annette. 1989. Contribution to The Spectatrix. camera obscura 2021:

21316.

. 2003. Living within the Frame. Inaugural lecture, University of Lancaster, June 11.

Metz, Christian. 1982. The Imaginary Signifier. In his Psychoanalysis and Cinema: The Imaginary Signifier. Trans. Ben Brewster. London: Macmillan.

Rose, Jacqueline. 1986. The Cinematic Apparatus: Problems in Current Theory.

In her Sexuality in the Field of Vision, 199213. London: Verso.

Staiger, Janet. 1995. Bad Women: Regulating Sexuality in Early American Cinema.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Studlar, Gaylyn. 1984. Masochism and the Perverse Pleasures of Cinema. Quarterly Review of Film Studies 9(4):26782.

Winnicott, D. W. 1971. The Location of Cultural Experience. In his Playing

and Reality, 95103. London: Tavistock.

This content downloaded from 193.137.168.1 on Sat, 22 Aug 2015 09:48:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- LG LFX31945 Refrigerator Service Manual MFL62188076 - Signature2 Brand DID PDFДокумент95 страницLG LFX31945 Refrigerator Service Manual MFL62188076 - Signature2 Brand DID PDFplasmapete71% (7)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- (Richard Dyer) The Role of StereotypesДокумент6 страниц(Richard Dyer) The Role of StereotypesCeiça Ferreira0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- (Amelia Simpson) Xuxa and The Politics of GenderДокумент13 страниц(Amelia Simpson) Xuxa and The Politics of GenderCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- Management Accounting by Cabrera Solution Manual 2011 PDFДокумент3 страницыManagement Accounting by Cabrera Solution Manual 2011 PDFClaudette Clemente100% (1)

- (Stephanie Dennison) Representation of Blondness On The Brazilian Big ScreenДокумент14 страниц(Stephanie Dennison) Representation of Blondness On The Brazilian Big ScreenCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- Stereotypes of African American Women in US TelevisionДокумент50 страницStereotypes of African American Women in US TelevisionCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- Da Transexualidade Oficial As TransexualidadesДокумент17 страницDa Transexualidade Oficial As TransexualidadesCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- Alcoff Racism and Visible Race CH 8 PDFДокумент345 страницAlcoff Racism and Visible Race CH 8 PDFMarcelo Vial RoeheОценок пока нет

- Seale Chapter 11Документ25 страницSeale Chapter 11sunru24Оценок пока нет

- Roubling Race. Using Judith Butler's Work To Think About Racialised Bodies and Selves.Документ15 страницRoubling Race. Using Judith Butler's Work To Think About Racialised Bodies and Selves.Ceiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- (Teresa de Lauretis) Feminism and Its DifferencesДокумент8 страниц(Teresa de Lauretis) Feminism and Its DifferencesCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- (Gyan Prakash) Subaltern Studies As Postcolonial Criticism PDFДокумент16 страниц(Gyan Prakash) Subaltern Studies As Postcolonial Criticism PDFCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- Gilman Racial NoseДокумент14 страницGilman Racial NoseCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- (Yasmin Jiwani) Race and The Media - A Retrospective and Prospective GazeДокумент6 страниц(Yasmin Jiwani) Race and The Media - A Retrospective and Prospective GazeCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- (Sandra Azevedo) - Teorizando Relações de Gênero e Relações RaciaisДокумент15 страниц(Sandra Azevedo) - Teorizando Relações de Gênero e Relações RaciaisCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- (Teresa de Lauretis) Feminism and Its DifferencesДокумент8 страниц(Teresa de Lauretis) Feminism and Its DifferencesCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- (Teresa de Lauretis) Feminism and Its DifferencesДокумент8 страниц(Teresa de Lauretis) Feminism and Its DifferencesCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- (Shubha Bhttacharya) Intersectionality Bell HooksДокумент32 страницы(Shubha Bhttacharya) Intersectionality Bell HooksCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- (Teresa de Lauretis) Feminism and Its DifferencesДокумент8 страниц(Teresa de Lauretis) Feminism and Its DifferencesCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- Sander GilmanДокумент20 страницSander GilmanSaúl Hernández VargasОценок пока нет

- The Cinema Book - Feminist Film Theory - Anneke Smelik PDFДокумент17 страницThe Cinema Book - Feminist Film Theory - Anneke Smelik PDFflor.del.cerezoОценок пока нет

- (Grace D. Gipson) Black SuperheroineДокумент141 страница(Grace D. Gipson) Black SuperheroineCeiça FerreiraОценок пока нет

- Vetoset CA541: Thickbed Cementitious Tile AdhesiveДокумент2 страницыVetoset CA541: Thickbed Cementitious Tile Adhesivemus3b1985Оценок пока нет

- Installing Surge Protective Devices With NEC Article 240 and Feeder Tap RuleДокумент2 страницыInstalling Surge Protective Devices With NEC Article 240 and Feeder Tap RuleJonathan Valverde RojasОценок пока нет

- Use of The Internet in EducationДокумент23 страницыUse of The Internet in EducationAlbert BelirОценок пока нет

- MATH CIDAM - PRECALCULUS (Midterm)Документ4 страницыMATH CIDAM - PRECALCULUS (Midterm)Amy MendiolaОценок пока нет

- Gas Compressor SizingДокумент1 страницаGas Compressor SizingNohemigdeliaLucenaОценок пока нет

- L GSR ChartsДокумент16 страницL GSR ChartsEmerald GrОценок пока нет

- How Transformers WorkДокумент15 страницHow Transformers Worktim schroderОценок пока нет

- Scrum Exam SampleДокумент8 страницScrum Exam SampleUdhayaОценок пока нет

- Waste Biorefinery Models Towards Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy Critical Review and Future Perspectives2016bioresource Technology PDFДокумент11 страницWaste Biorefinery Models Towards Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy Critical Review and Future Perspectives2016bioresource Technology PDFdatinov100% (1)

- Does Adding Salt To Water Makes It Boil FasterДокумент1 страницаDoes Adding Salt To Water Makes It Boil Fasterfelixcouture2007Оценок пока нет

- 11-Rubber & PlasticsДокумент48 страниц11-Rubber & PlasticsJack NgОценок пока нет

- Intelligent Status Monitoring System For Port Machinery: RMGC/RTGCДокумент2 страницыIntelligent Status Monitoring System For Port Machinery: RMGC/RTGCfatsahОценок пока нет

- Principled Instructions Are All You Need For Questioning LLaMA-1/2, GPT-3.5/4Документ24 страницыPrincipled Instructions Are All You Need For Questioning LLaMA-1/2, GPT-3.5/4Jeremias GordonОценок пока нет

- MPI Unit 4Документ155 страницMPI Unit 4Dishant RathiОценок пока нет

- 2007 ATRA Seminar ManualДокумент272 страницы2007 ATRA Seminar Manualtroublezaur100% (3)

- Jinivefsiti: Sultan LorisДокумент13 страницJinivefsiti: Sultan LorisSITI HAJAR BINTI MOHD LATEPIОценок пока нет

- Configuration Guide - Interface Management (V300R007C00 - 02)Документ117 страницConfiguration Guide - Interface Management (V300R007C00 - 02)Dikdik PribadiОценок пока нет

- File RecordsДокумент161 страницаFile RecordsAtharva Thite100% (2)

- CM2192 - High Performance Liquid Chromatography For Rapid Separation and Analysis of A Vitamin C TabletДокумент2 страницыCM2192 - High Performance Liquid Chromatography For Rapid Separation and Analysis of A Vitamin C TabletJames HookОценок пока нет

- I. Choose The Best Option (From A, B, C or D) To Complete Each Sentence: (3.0pts)Документ5 страницI. Choose The Best Option (From A, B, C or D) To Complete Each Sentence: (3.0pts)thmeiz.17sОценок пока нет

- BECED S4 Motivational Techniques PDFДокумент11 страницBECED S4 Motivational Techniques PDFAmeil OrindayОценок пока нет

- English For Academic and Professional Purposes - ExamДокумент3 страницыEnglish For Academic and Professional Purposes - ExamEddie Padilla LugoОценок пока нет

- Tribes Without RulersДокумент25 страницTribes Without Rulersgulistan.alpaslan8134100% (1)

- 5steps To Finding Your Workflow: by Nathan LozeronДокумент35 страниц5steps To Finding Your Workflow: by Nathan Lozeronrehabbed100% (2)

- The University of The West Indies: Application For First Degree, Associate Degree, Diploma and Certificate ProgrammesДокумент5 страницThe University of The West Indies: Application For First Degree, Associate Degree, Diploma and Certificate ProgrammesDavid Adeyinka RamgobinОценок пока нет

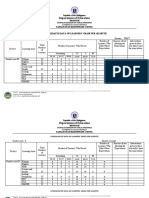

- Department of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterДокумент4 страницыDepartment of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterUsagi HamadaОценок пока нет

- Log and Antilog TableДокумент3 страницыLog and Antilog TableDeboshri BhattacharjeeОценок пока нет

- Digital Systems Project: IITB CPUДокумент7 страницDigital Systems Project: IITB CPUAnoushka DeyОценок пока нет