Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Diagnostic Criteria For Central Versus Peripheral Positioning Nystagmus and

Загружено:

RudolfGerОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Diagnostic Criteria For Central Versus Peripheral Positioning Nystagmus and

Загружено:

RudolfGerАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1999; 119: 1 5

Diagnostic Criteria for Central versus Peripheral Positioning Nystagmus and

Vertigo: a Review

U. BU8 TTNER, CH. HELMCHEN and TH. BRANDT

From the Department of Neurology, Uni6ersity of Munich, Munich, Germany

Buttner U, Helmchen Ch, Brandt Th. Diagnostic criteria for central 6ersus peripheral positioning nystagmus and 6ertigo.

Acta Otolaryngol (Stockholm) 1999; 119: 15.

Head positioning can lead to pathological nystagmus and vertigo. In most instances the cause is a peripheral vestibular

disorder, as in benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo (BPPV). Central lesions can lead to positional nystagmus (central

PN) or to paroxysmal positioning nystagmus and vertigo (central PPV). Lesions in central PPV are often found

dorsolateral to the fourth ventricle or in the dorsal vermis. This localization, together with other clinical features

(associated cerebellar and oculomotor signs), generally allows one to easily distinguish central PPV from BPPV. However,

in individual cases this may prove difficult, since the two syndromes share many features. Even if only BPPV as a

peripheral lesion is considered, differentiation based on such features as latency, course, and duration of nystagmus during

an attack, fatigability, vertigo, vomiting, and time period during which nystagmus bouts occur, may be impossible. Only

the direction of nystagmus during an attack can allow differentiation. Key words: central positioning nystagmus, central

positioning 6ertigo, paroxysmal nystagmus, paroxysmal 6ertigo.

INTRODUCTION

A specific change in head position can, under pathological conditions, cause nystagmus that outlasts the

head movement. It is necessary to distinguish between positioning and positional nystagmus: the

former term implies that the actual head movement is

the cause, whereas the term positional indicates

that the new head position (which has a different

otolith input) causes the nystagmus. Basically, three

types of peripheral or central positional/positioning

nystagmus (PN) have been distinguished (1): (i) In

cases of PN I, or central positional nystagmus (central PN), the nystagmus lasts as long as the head

remains in the precipitating position. It is usually of

central origin (2) and not combined with vertigo. (ii)

PN II, or benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo

(BPPV), is caused by a peripheral canal disorder;

vertigo is a dominant feature. (iii) PN III or central

positioning nystagmus and vertigo (central PPV) is

caused by a central lesion and consists of short-lasting nystagmus combined with vertigo. This disorder

has also been called pseudo-BPPN (3).

The absence of vertigo and the presence of sustained nystagmus during the precipitating head position for central PN usually allows one to easily

distinguish BPPV and central PPV. However, it is not

as easy to distinguish between BPPV and central PPV

with paroxysmal nystagmus and vertigo present.

BPPV was first described by Barany in 1921 (4).

The term itself was introduced by Dix and Hallpike

in 1952 (5). In the past, widely accepted criteria were

developed for the diagnosis of BPPV. Since in most

instances the posterior canal (PC) is affected, a head

movement in the PC plane from the erect sitting

1999 Scandinavian University Press. ISSN 0001-6489

position to the affected side leads, with a latency of

several seconds, to nystagmus, which beats to the

undermost ear. It lasts 530 sec and is accompanied

by vertigo. Deviations from this uniform pattern are

usually believed to indicate a central origin.

There has been considerable progress over recent

years in understanding the pathophysiology of BPPV.

This, in turn, has made possible the identification of

new clinical features for nystagmus of peripheral

origin which definitively do not fit the classic picture

of BPPV. First, it has been argued that BPPV is in

most instances due to canalolithiasis and not cupulolithiasis (6). Only rarely do clinical signs indicate

cupulolithiasis (7). In such instances the nystagmus is

not paroxysmal but ongoing, with only mild and

long-lasting vertigo (7, 8). Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that not only the posterior but also

the horizontal (9, 10) and rarely the anterior (8, 11)

canal can be affected. In cases of horizontal canal

BPPV (h-BPPV), the nystagmus beats in the horizontal direction and can beat toward the uppermost ear,

oculomotor signs which earlier were assumed to indicate a central disorder. Thus, the diagnosis and classification of central positioning versus peripheral

positioning nystagmus have become more difficult.

The correct evaluation of all criteria will certainly

improve diagnostic accuracy.

In the following we compare the main features of

central and peripheral PN. As peripheral PN, only

BPPV and not other possible causes (Menie`res disease, perilymph fistulas, drug or alcohol intoxication)

are considered. It is shown that most of the traditional features are not suitable for distinguishing

them clearly. There is one feature that does allow

U. Buttner et al.

such differentiation, however: in a peripheral disorder, the resulting nystagmus always beats in the

direction of the expected eye movements if the affected semicircular canal is optimally stimulated.

Thus, the nystagmus in h-BPPV always beats horizontally and is elicited by stimulation in the horizontal

plane. This does not have to be the case for central

paroxysmal PN (central PPV).

MAIN FEATURES OF PERIPHERAL AND

CENTRAL PAROXYSMAL PN AND VERTIGO

Latency

In cases of posterior canal BPPV (p-BPPV), the

latency is 215 sec and decreases with increasing

speed of the positioning manoeuvre (12). In h-BPPV

there can be virtually no latency (13). In patients with

central PPV either no latency (14, 15) or latencies up

to 35 sec (16) have been encountered. In experimental lesions of the dorsal vermis (nodulus), latencies can

vary between 0 and 50 sec (17, 18).

Duration of an attack

P-BPPV typically lasts between 5 and 30 sec (12). In

the static position some continuous subtle nystagmus

can be present; this has been reported in 40% of these

patients (8). H-BPPV usually lasts about 1 min and

thus longer than p-BPPV (10).

In patients with central PPV the attack can last

from a few seconds (5 6 sec (19); 15 sec (14)) up to

1 min (20). In experimental lesions of the dorsal

vermis, the duration of central PPV is 30 180 sec

(18).

Direction of nystagmus

The posterior canal (p-BPPV) is most often affected in

BPPV. During the investigation, the head of the

sitting patient is turned 45 to bring the PC into the

plane of stimulation before the body is tilted to the

side. This leads to ampullofugal movements of the

particles within the PC and as a result to activation of

the superior oblique muscle of the ipsilateral eye and

the inferior rectus muscle of the contralateral eye.

The induced nystagmus consists of vertical and

torsional components which rotate around an axis

perpendicular to the PC. The fast phase has an

upward component and beats torsionally toward the

undermost ear (geotropic). This latter component

becomes more pronounced when the patient looks in

the direction of the uppermost ear (21). Although

bilateral p-BPPV may not be uncommon (22), the

improper positioning of the patient often leads to this

false diagnosis. Only when proper positioning is ensured does nystagmus to the undermost ear

(geotropic) during left and right positioning manoeu-

Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 119

vres indicate a bilateral involvement (7).

In cases of the rarely described BPPV of the anterior canal (a-BPPV), the vertical component of the

rotatory-linear nystagmus beats downward (toward

the chin) after the positioning manoeuvre (8, 11).

While horizontal canal BPPV (h-BPPV) is more

often encountered than a-BPPV, it is still much less

common than p-BPPV. The nystagmus of h-BPPV is

purely horizontal and beats to the undermost ear

(geotropic), following left as well as right head rotations of the supine patient. Although this does not

allow one to determine which ear is affected, the

nystagmus is usually more pronounced in the direction of the affected ear. Toward the end of an attack

when the head is stable, the nystagmus can sometimes

reverse its direction. This has been attributed to

adaptation similar to that observed in nystagmus

reversal during postrotatory nystagmus (P I and P II)

(9, 10). In cases of h-BPPV also horizontal nystagmus

beating to the uppermost ear (apogeotropic) right

from the beginning has been described and attributed

to HC cupulolithiasis instead of canalolithiasis (13,

23).

The positioning manoeuvre in patients with central

lesions can elicit paroxysmal nystagmus, which can be

downbeat in the head-hanging position (24), counterclockwise in the right-hanging position (19), downbeat and left beating in the left-hanging position (14),

upbeat in the supine position (14), or torsional with

positioning (3).

In experimental central lesions, the positioning manoeuvre leads to paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus

(when the animal is brought into the supine position)

(17), occasionally with a torsional component (18).

Horizontal nystagmus after a return to the supine

position has also been observed (17).

Fatigability

Fatigability refers to the response to repeated provocations and not to the duration of an attack. It is

generally also considered a diagnostic criterion for

peripheral BPPV. This certainly applies for p-BPPV;

however, h-BPPV does not easily fatigue. This is

explained by the hypothesis that the dislocated particles within the canal are large enough to prevent easy

disappearance from the canal (7). Fatigability is definitely also seen in central PPV in both, patients (14, 20,

24) and experimental animals (17), with dorsal vermal

lesions. However, there are also several reports of

patients without fatigability of central PPV (3, 14).

Course of nystagmus during an attack

The crescendodecrescendo type of nystagmus is considered typical for p-BPPV. It is, however, not a

Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 119

common feature of h-BPPV (7). A crescendo

decrescendo type of nystagmus is also seen in central

PPV in patients (3) and experimental animals (18).

Thus, a distinction between peripheral and central

origin cannot be made on the basis of the course of

the nystagmus during an attack.

Vertigo

Vertigo is obligatory in peripheral BPPV and is also

generally encountered in central PPV (14, 16, 24). As

mentioned above, vertigo is not a feature of central

positional nystagmus (central PN).

Vomiting

Vomiting is not uncommon in either peripheral

BPPV or central PPV (16). Particularly, in BPPV

vomiting usually correlates with nystagmus intensity

(slow-phase velocity). A dissociation is possible in

central PPV. Drachman et al. (20) described two

patients with posturally-evoked vomiting (PEV)

due to posterior fossa lesions: they exhibited only a

few nystagmoid jerks after positioning or no nystagmus at all.

Natural course/prognosis

In BPPV, the attacks with nystagmus and vertigo

generally subside within several weeks but may last

(including intermediate remissions) in some instances

up to several years (8). This is the natural course

without treatment (physical therapy). However, spontaneous recovery from central PPV after several

weeks has also been reported for dorsal vermis lesions in experimental animals (17) and in patients

with PEV (20).

Associated clinical features

For BPPV there are usually normal findings on neurological and other clinical tests. Sometimes caloric

hypoexcitability of the affected ear is encountered for

p-BPPV (8) as well as h-BPPV (25). Also directional

preponderance to caloric stimulation has been encountered for p-BPPV (8). Cerebellar and oculomotor abnormalities are often seen in central PPV;

however, it is not uncommon for patients to have

otherwise normal eye movements (19) and a completely normal neurological evaluation (14, 16).

Brain imaging

Brain imaging (CT, MRI) of patients with peripheral

BPPV is, of course, normal. Most patients with central PPV exhibit lesions dorsolateral to the fourth

ventricle (26) or of the vermis (27), particularly the

dorsal vermis (3, 14, 16, 19, 24), a site which is

compatible with experimental studies (17, 18). It

should be stressed that there are also a few cases (16,

Central 6s peripheral positioning nystagmus

20) in which the initial CT did not show evidence of

a tumour or a defined posterior fossa lesion, which

was found only months (20) or years (16) later.

DISCUSSION

There is no doubt that p-BPPV is the most common

form of paroxysmal nystagmus with vertigo. Usually

this disorder can be easily recognized. Peripheral

h-BPPV and a-BPPV as well as central PPV are

considerably less frequent. As outlined above, the

distinction between a peripheral and a central origin

for paroxysmal nystagmus can be difficult if most

features are considered in detail (Table I). This certainly applies to latency of onset of symptoms after

positioning, duration of nystagmus bouts, course of

nystagmus during an attack, and vertigo. However,

the direction of nystagmus is a major feature that can

allow a clear distinction. When stimulated in the

appropriate plane, the nystagmus in p-BPPV always

has a combined vertical upward and torsional component, which is the result of the PC-mediated muscle

activation. The very rare a-BPPV also leads to eye

movements with torsional and vertical components,

and in this instance a vertical-downward component.

With HC stimulation the eye movements are always

in the horizontal plane. For h-BPPV the nystagmus

that occurs when the left ear or right ear is in the

down position can be directed to the undermost

(geotropic) or uppermost (apogeotropic) ear (13, 23).

Thus, this feature (geotropic or apogeotropic) cannot

be used to differentiate a peripheral or central origin.

Paroxysmal downbeat, upbeat, or torsional nystagmus must be due to lesions of central origin. Theoretically, a symmetrical bilateral p-BPPV could lead to

paroxysmal upbeat nystagmus when the head is

brought into the head-hanging position. This, however, would require identical conditions on both

sides, which is unlikely and has not been observed so

far. Similarly, stimulation of the horizontal canals,

e.g. during head shaking, cannot lead to torsional

nystagmus or vertical nystagmus if a peripheral disorder is the suspected cause. The same applies to horizontal nystagmus after stimulation of the vertical

canals. Such a pattern also has to have a central

origin (17).

Nystagmus and vertigo are highly correlated in

p-BPPV. This also generally applies to vomiting.

Vomiting in BPPV without intense nystagmus should

be considered unusual and prompt further observation or examinations.

Cases of central PPV are generally accompanied by

additional neurological, particularly oculomotor

signs, such as saccadic pursuit and gaze-evoked nystagmus, which facilitates the diagnosis of central

U. Buttner et al.

Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 119

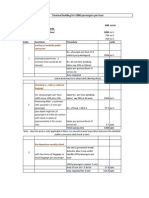

Table I. Clinical features of peripheral benign paroxysmal positioning 6ertigo/nystagmus (BPPV) and central

paroxysmal positioning 6ertigo/nystagmus (central PPV)

Features

BPPV

Central PPV

Latency following precipitating

positioning manoeuvre

Duration of attack

Direction of nystagmus

115 sec (shorter in h-BPPV)

05 sec

560 sec (longer in h-BPPV)

During stimulation in the plane of

the affected canal: torsional/vertical

for p-BPPV and a-BPPV; horizontal

for h-BPPV

Typical, rare in h-BPPV

Crescendodecrescendo typical, not

common in h-BPPV

Typical

Rare on single precipitating

manoeuvres (associated with intense

nystagmus), not uncommon after

several manoeuvres

Spontaneous recovery within several

weeks in 7080%

None

5B60 sec

Pure vertical; pure torsional, not

attributable to the stimulated canal

plane

Fatigability

Course of nystagmus and vertigo

in an attack

Vertigo

Nausea and vomiting

Natural course of the condition

Associated neurological signs

and symptoms

Brain imaging

Normal

Possible

Crescendodecrescendo possible

Typical

Frequent on single precipitating

manoeuvres (not necessarily associated

with strong nystagmus intensities)

Spontaneous recovery within weeks

possible

None possible, often cerebellar and

other oculomotor signs

Normal; lesions of the dorsal vermis

and/or dorsolateral to the fourth

ventricle

a =anterior, h =horizontal and p =posterior canal.

origin. However, in some instances the neurological

examination and brain imaging can be normal (16).

Thus, with better understanding of the underlying

mechanisms of BPPV and the detailed clinical descriptions not only of p-BPPV, but also of h- and

a-BPPV, many features can no longer reliably be used

to distinguish between a peripheral or a central origin

of nystagmus combined with vertigo. These features

include latency, a horizontal direction of nystagmus,

fatigability, and the crescendo decrescendo type of

nystagmus during an attack. A central origin has to

be assumed for upbeat, downbeat, and pure torsional

nystagmus, which cannot be caused by a (single)

peripheral lesion. Furthermore, in cases of a peripheral lesion, the provoked eye movements have to

correspond to the stimulated canal plane, i.e., stimulation of an affected horizontal canal cannot lead to

torsional nystagmus. Of course, it is also still valid

that positional or positioning nystagmus without vertigo (central PN) indicates a central lesion.

A lesion in the posterior fossa either dorsolateral to

the fourth ventricle (26) or in the dorsal vermis (14,

24) is generally found in central PPV. This is usually

due to a tumour (14, 16) or haemorrhages (24, 26).

Infarction appears to be seldom the cause, in contrast

to its frequency of occurrence.

Thus, experimental and clinical studies indicate

that two cerebellar locations can be related to the

occurrence of central PPV. One involves the nodulus/

uvula region. It is mainly bilateral, but unilateral

lesions can also cause central PPV (personal observation). The other location is in the vicinity of, but

clearly separate from, the nodulus/uvula region dorsolateral to the fourth ventricle (26). This lesion is

always unilateral and has only been observed in

humans so far. The precise structures involved for

this location are not known (26). In conclusion,

peripheral BPPV is a common disorder that can be

easily diagnosed when the appropriate canal stimulation planes are considered. The less common central

PPV can usually be identified after a full examination

with brain imaging. In a few instances this may not

be possible. In such situations only the direction of a

nystagmus after the positioning manoeuvre can

provide clear signs of a central disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank B. Pfreundner and I. Wendl for typing

the manuscript and J. Benson for improving the English.

REFERENCES

1. Harrison MS, Ozsahinoglu C. Positional vertigo: aetiology and clinical significance. Brain 1972; 95: 36972.

2. Nylen CO. The oto-neurological diagnosis of tumours

of the brain. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh) 1939;

33: 1 151.

3. Sakata E, Ohtsu K, Shimura H, Sakai S. Positional

nystagmus of benign paroxysmal type (BPPN) due to

Central 6s peripheral positioning nystagmus

Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 119

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

cerebellar vermis lesions. Pseudo-BPPN. Auris Nasus

Larynx 1987; 14: 1721.

Barany R. Diagnose von Krankheitserscheinungen im

Bereiche des Otolithenapparates. Acta Otolaryngol

(Stockh) 1921; 2: 4347.

Dix R, Hallpike CS. The pathology, symptomatology

and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the

vestibular system. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1952; 6:

9871016.

Brandt T, Steddin S. Current view of the mechanism of

benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo: cupulolithiasis

or canalolithiasis? J Vestib Res 1993; 3: 37382.

Steddin S, Brandt T. Benigner paroxysmaler

Lagerungsschwindel. Nervenarzt 1994; 65: 505 10.

Baloh RW, Honrubia V, Jacobson K. Benign positional vertigo: clinical and oculographic features in 240

cases. Neurology 1987; 37: 3718.

Pagnini P, Nuti D, Vannuncchi P. Benign paroxysmal

vertigo of the horizontal canal. ORL 1989; 51: 161 70.

Baloh RW, Jacobson K, Honrubia V. Horizontal semicircular canal variant of benign positional vertigo.

Neurology 1993; 43: 25429.

Herdman SJ, Tusa RJ. Complications of the canalith

repositioning procedure. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck

Surg 1996; 122: 2816.

Baloh RW, Sakala SM, Honrubia V. Benign paroxysmal positional nystagmus. Am J Otolaryngol 1979; 1:

16.

Steddin S, Brandt T. Horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo (h-BPPV): transition of

canalolithiasis to cupulolithiasis. Ann Neurol 1996; 40:

91822.

Gregorius FK, Crandall PH, Baloh RW. Positional

vertigo with cerebellar astrocytoma. Surg Neurol 1976;

6: 2836.

Jacobson GP, Butcher JA, Newman CW, Monsell EM.

When paroxysmal positioning vertigo isnt benign. J

Am Acad Audiol 1995; 6: 3469.

Watson CP, Barber HO, Peck J, Terbrugge K. Positional vertigo and nystagmus of central origin. Can J

Neurol Sci 1981; 8: 1337.

Allen G, Fernandez C. Experimental observations in

postural nystagmus: extensive lesions in posterior ver-

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

mis of the cerebellum. Acta Otolaryngol 1960; 51:

2 14.

Fernandez C, Alzate R, Lindsay JR. Experimental

observations on postural nystagmus. II lesions of the

nodulus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1960; 69: 94 114.

Barber HO. Positional nystagmus. Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg 1984; 92: 649 55.

Drachman DA, Diamond ER, Hart CW. Posturally

evoked vomiting: association with posterior fossa lesions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1977; 86: 97 101.

Brandt T. Positional and positioning vertigo and nystagmus. J Neurol Sci 1990; 95: 3 28.

Longridge NS, Barber HO. Bilateral paroxysmal positioning nystagmus. J Otolaryngol 1978; 7: 395 400.

Baloh RW, Yue Q, Jacobson KM, Honrubia V. Persistent direction-changing positional nystagmus: another

variant of benign positional nystagmus? Neurology

1995; 45: 1297 301.

Kattah JC, Kolsky MP, Luessenhop AJ. Positional

vertigo and the cerebellar vermis. Neurology 1984; 34:

5279.

Strupp M, Brandt T, Steddin S. Horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo: reversible ipsilateral caloric hypoexcitability caused by canalolithiasis?

Neurol 1995; 45: 2072 6.

Brandt T. Vertigo its multisensory syndromes. London: Springer Verlag, 1991.

Watson CP, Terbrugge K. Positional nystagmus of the

benign paroxysmal type with posterior fossa medulloblastoma. Arch Neurol 1982; 39: 601 2.

Submitted March 2, 1998; accepted September 11, 1998

Address for correspondence:

U. Buttnerm, MD

Neurologische Klinik

Klinikum Grohadern

Marchioninistrae 15

DE-81377 Munchen

Germany

Tel: + 49 89 7095 2560

Fax: + 49 89 7095 8883

E-mail: ubuettner@brain.nefo.med.uni-muenchen.de

Вам также может понравиться

- VNG CB en Rev02 - HDДокумент5 страницVNG CB en Rev02 - HDRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- A Simple Gain-Based Evaluation of The Video Head Impulse Test Reliably Detects Normal Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Indicative of Stroke in Patients With Acute Vestibular SyndromeДокумент8 страницA Simple Gain-Based Evaluation of The Video Head Impulse Test Reliably Detects Normal Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Indicative of Stroke in Patients With Acute Vestibular SyndromeRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Effect of Spatial Orientation of The Horizontal Semicircular Canal On The Vestibulo-Ocular ReflexДокумент8 страницEffect of Spatial Orientation of The Horizontal Semicircular Canal On The Vestibulo-Ocular ReflexRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Persistent Geotropic and Apogeotropic Positional Nystagmus of The Lateral Canal Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoДокумент6 страницAnalysis of Persistent Geotropic and Apogeotropic Positional Nystagmus of The Lateral Canal Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Abnormal Cancellation of The Vestibulo-Ocular ReflexДокумент4 страницыAbnormal Cancellation of The Vestibulo-Ocular ReflexRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Causes and Characteristics of Horizontal Positional NystagmusДокумент9 страницCauses and Characteristics of Horizontal Positional NystagmusRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Head-Jolting Nystagmus Occlusion of The Horizontal Semicircular Canal Induced by Vigorous Head ShakingДокумент4 страницыHead-Jolting Nystagmus Occlusion of The Horizontal Semicircular Canal Induced by Vigorous Head ShakingRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Latest Statistics On England Mortality Data Suggest Systematic Mis-Categorisation of Vaccine Status and Uncertain Effectiveness of Covid-19Документ24 страницыLatest Statistics On England Mortality Data Suggest Systematic Mis-Categorisation of Vaccine Status and Uncertain Effectiveness of Covid-19RudolfGerОценок пока нет

- COVID-19 and Compulsory Vaccination - AnДокумент24 страницыCOVID-19 and Compulsory Vaccination - AnRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Pelvic Pain With Sitting: Diagnostic Algorithm: A. Lee Dellon, MD, PHD, Johns Hopkins UniversityДокумент1 страницаPelvic Pain With Sitting: Diagnostic Algorithm: A. Lee Dellon, MD, PHD, Johns Hopkins UniversityRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Cervical Spine Pre-Screening For Arterial DysfunctionДокумент11 страницCervical Spine Pre-Screening For Arterial DysfunctionRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Concussion Guidelines Step 2 - Evidence For Subtype ClassificationДокумент12 страницConcussion Guidelines Step 2 - Evidence For Subtype ClassificationRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- Fall Prediction in Neurological Gait Disorders DifДокумент15 страницFall Prediction in Neurological Gait Disorders DifRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- The Spectrum of Vestibular MigraineДокумент14 страницThe Spectrum of Vestibular MigraineRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- A Pilot Study To Evaluate Multi-Dimensional Effects of Dance For People With Parkinson's DiseaseДокумент6 страницA Pilot Study To Evaluate Multi-Dimensional Effects of Dance For People With Parkinson's DiseaseRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- The Treatment of Chronic Coccydynia With PDFДокумент7 страницThe Treatment of Chronic Coccydynia With PDFRudolfGerОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- 10 Ideas For ConversationДокумент116 страниц10 Ideas For ConversationGreenLake36100% (1)

- SHARE SEA Outlook Book 2518 r120719 2Документ218 страницSHARE SEA Outlook Book 2518 r120719 2Raafi SeiffОценок пока нет

- Wollo UniversityДокумент14 страницWollo UniversityabdishakurОценок пока нет

- Product Bulletin Fisher 8580 Rotary Valve en 123032Документ16 страницProduct Bulletin Fisher 8580 Rotary Valve en 123032Rachmat MaulanaОценок пока нет

- Medical and Health Care DocumentДокумент6 страницMedical and Health Care Document786waqar786Оценок пока нет

- đề thi TAДокумент15 страницđề thi TAĐào Nguyễn Duy TùngОценок пока нет

- Bow Thruster CatalogLRДокумент28 страницBow Thruster CatalogLRAlexey RulevskiyОценок пока нет

- Simple Future TenseДокумент14 страницSimple Future TenseYupiyupsОценок пока нет

- Igice Cya Kabiri: 2.0. Intambwe Zitandukanye Z'Imikorere Ya Mariyamu KinyamaruraДокумент7 страницIgice Cya Kabiri: 2.0. Intambwe Zitandukanye Z'Imikorere Ya Mariyamu KinyamaruraJacques Abimanikunda BarahirwaОценок пока нет

- Shanu Return Ticket To Sobani HostelДокумент1 страницаShanu Return Ticket To Sobani HostelTamseel ShahajahanОценок пока нет

- Fig. 6.14 Circular WaveguideДокумент16 страницFig. 6.14 Circular WaveguideThiagu RajivОценок пока нет

- AS Unit 1 Revision Note Physics IAL EdexcelДокумент9 страницAS Unit 1 Revision Note Physics IAL EdexcelMahbub Khan100% (1)

- Homa Pump Catalog 2011Документ1 089 страницHoma Pump Catalog 2011themejia87Оценок пока нет

- 3 - Accounting For Loans and ImpairmentДокумент1 страница3 - Accounting For Loans and ImpairmentReese AyessaОценок пока нет

- Prgm-Sminr Faculties Identified Through FIP NIRCДокумент9 страницPrgm-Sminr Faculties Identified Through FIP NIRCDonor CrewОценок пока нет

- Nclex PogiДокумент8 страницNclex Pogijackyd5Оценок пока нет

- Tinniuts Today March 1990 Vol 15, No 1Документ19 страницTinniuts Today March 1990 Vol 15, No 1American Tinnitus AssociationОценок пока нет

- Bus Terminal Building AreasДокумент3 страницыBus Terminal Building AreasRohit Kashyap100% (1)

- Estudio - Women Who Suffered Emotionally From Abortion - A Qualitative Synthesis of Their ExperiencesДокумент6 страницEstudio - Women Who Suffered Emotionally From Abortion - A Qualitative Synthesis of Their ExperiencesSharmely CárdenasОценок пока нет

- El Poder de La Disciplina El Hábito Que Cambiará Tu Vida (Raimon Samsó)Документ4 страницыEl Poder de La Disciplina El Hábito Que Cambiará Tu Vida (Raimon Samsó)ER CaballeroОценок пока нет

- Lesson 3 POWERДокумент25 страницLesson 3 POWERLord Byron FerrerОценок пока нет

- AWSCertifiedBigDataSlides PDFДокумент414 страницAWSCertifiedBigDataSlides PDFUtsav PatelОценок пока нет

- PHMSA Amended Corrective Action Order For Plains All American Pipeline Regarding Refugio Oil Spill in Santa Barbara CountyДокумент7 страницPHMSA Amended Corrective Action Order For Plains All American Pipeline Regarding Refugio Oil Spill in Santa Barbara Countygiana_magnoliОценок пока нет

- Business Analytics Case Study - NetflixДокумент2 страницыBusiness Analytics Case Study - NetflixPurav PatelОценок пока нет

- Price Negotiator E-CommerceДокумент17 страницPrice Negotiator E-Commerce20261A3232 LAKKIREDDY RUTHWIK REDDYОценок пока нет

- Way of St. LouiseДокумент18 страницWay of St. LouiseMaryann GuevaradcОценок пока нет

- Group6 Business-Proposal Delivery AppДокумент15 страницGroup6 Business-Proposal Delivery AppNathaniel Karl Enin PulidoОценок пока нет

- 2016 ILA Berlin Air Show June 1 - 4Документ11 страниц2016 ILA Berlin Air Show June 1 - 4sean JacobsОценок пока нет

- At The End of The Lesson, The Students Will Be Able To Apply The Indefinite Articles in The Given SentencesДокумент11 страницAt The End of The Lesson, The Students Will Be Able To Apply The Indefinite Articles in The Given SentencesRhielle Dimaculangan CabañezОценок пока нет

- Resume Kantesh MundaragiДокумент3 страницыResume Kantesh MundaragiKanteshОценок пока нет