Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Separate Streams in Emergency Room

Загружено:

hannahАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Separate Streams in Emergency Room

Загружено:

hannahАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 6, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.

com

28

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The effect of a separate stream for minor injuries on

accident and emergency department waiting times

M W Cooke, S Wilson, S Pearson

.............................................................................................................................

Emerg Med J 2002;19:2830

See end of article for

authors affiliations

.......................

Correspondence to:

Dr M W Cooke,

Emergency Medicine

Research Group, Centre for

Primary Health Care

Studies, University of

Warwick, Coventry

CV4 7AL, UK;

matthew.cooke@

warwick.ac.uk

Accepted for publication

11 June 2001

.......................

Introduction: To decrease waiting times within accident and emergency (A&E) departments, various

initiatives have been suggested including the use of a separate stream of care for minor injuries (fast

track). This study aimed to assess whether a separate stream of minor injuries care in a UK A&E

department decreases the waiting time, without delaying the care of those with more serious injury.

Intervention: A doctor saw any ambulant patients with injuries not requiring an examination couch or

an urgent intervention. Any patients requiring further treatment were returned to the sub-wait area until

a nurse could see them in another cubicle.

Method: Data were retrospectively extracted from the routine hospital information systems for all

patients attending the A&E department for five weeks before the institution of the separate stream system and for five weeks after.

Results: 13 918 new patients were seen during the 10 week study period; 7117 (51.1%) in the first

five week period and 6801 (49.9%) in the second five week period when a separate stream was

operational. Recorded time to see a doctor ranged from 0850 minutes. Comparison of the two five

week periods demonstrated that the proportion of patients waiting less than 30 and less than 60

minutes both improved (p<0.0001). The relative risk of waiting more than one hour decreased by 32%.

The improvements in waiting times were not at the expense of patients with more urgent needs.

Conclusions: The introduction of a separate stream for minor injuries can produce an improvement in

the number of trauma patients waiting over an hour of about 30%. If this is associated with an increase

in consultant presence on the shop floor it may be possible to achieve a 50% improvement. It is recommended that departments use a separate stream for minor injuries to decrease the number of patients

enduring long waits in A&E departments.

n order to decrease waiting times within A&E departments,

various initiatives have been introduced. The use of a separate stream of care for minor injuries has been suggested as

a way of decreasing the waiting time for a group of patients

who make up a large number of cases who, by definition, are

less urgent than other cases.1 This separate stream of patients

is often referred to as fast track.

A recent survey of accident and emergency (A&E)

departments for the Department of Health has demonstrated

that 41% have a system whereby quick cases are seen in a

separate area or by separate staff.2 Where such separate stream

systems are operating, patients are seen by a variety of staff:

any grade of staff (3% of departments), senior/middle grade

medical staff (19%), nurse practitioners (36%), or SHOs

(42%). Separate stream systems are often not used constantly

but brought into operation when busy or for specific

conditions such as fractured neck of femur (68% of

departments), suspected myocardial infarction (68%), for

critically ill/traumatised patients (46%) and 30% of departments have separate stream systems for other conditions such

as meningococcal disease, epistaxis and retention of urine.

Separate stream systems have been demonstrated to help

patients with several conditions, such as myocardial

infarction3 and fractured neck of femur.4 These studies have

not looked for any deleterious effect on other patients. Minor

injury separate streams have been shown to decrease waiting

time for specific groups of patients5 and to decrease the

number of complaints6 7 but were ineffective when there were

a lot of seriously ill patients in the department. None of the

previous studies identified were based in a UK system.

There have been no studies showing that a separate stream

of minor injuries care in a UK A&E department does decrease

the waiting time or any studies to demonstrate that it does not

www.emjonline.com

delay the care of those with more serious injury. This study

aimed to determine the effect of introducing a separate stream

for minor injuries on the waiting time for all patients in the

A&E department, according to triage category.

INTERVENTION

The separate minor injuries stream system involved the

conversion of one cubicle to a desk type consulting room. One

doctor (an SHO of at least four months experience, staff grade

or consultant following the same profile as seen by other

patients) was based in this room and saw any ambulant

patients with injuries not requiring an examination couch or

an urgent intervention (that is, triage category 4 or 5). The aim

was to have the next two patients sitting in a sub-wait area

immediately outside the room, so the doctor could call them in

without any delay. Any patients requiring further treatment

were returned to the sub-wait area until a nurse could see

them in another cubicle. In this way, the doctor in the fast

track room was continuously seeing patients. The system was

operational during the time period 0900 to 2300 (when there

were at least three doctors in the department). It was only

stopped when the department was exceptionally quiet and

doctors were seeing patients immediately after triage.

In the first week of the separate stream system, there was a

deliberately increased consultant presence in the clinical areas

of the A&E department. The consultants ensured that the system was being used. They did not specifically screen the separate stream cases or oversee the selection of cases. Cases that

were seen in the separate stream system but were then found

to need care that could not be given in that consulting room

were transferred to another area.

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 6, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

A&E waiting times

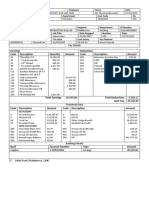

Table 1

29

Week of attendance and waiting time to treatment

Time from attendance to treatment

Week

Spoiled

<30 min

w/c 27.04.99

w/c 04.05.99

w/c 11.05.99

w/c 18.05.99

w/c 25.05.99

w/c 01.06.99

w/c 08.06.99

w/c 15.06.99

w/c 22.06.99

w/c 29.06.99

Total

13

1

5

1

11

1

5

7

7

6

57

0.4%

379

509

562

439

628

744

609

603

552

471

5496

39.5%

0.9%

0.1%

0.3%

0.1%

0.7%

0.1%

0.4%

0.5%

0.5%

0.5%

27.5%

36.8%

38.7%

30.7%

42.7%

57.3%

44.0%

40.6%

39.7%

37.9%

3060 min

>60 min

398

373

426

459

437

346

481

446

507

405

4278

30.7%

587

501

460

533

395

207

289

429

326

360

4087

29.4%

The staff in the department were aware that the new system

had been introduced but were not aware that this evaluation

was being undertaken.

METHODS

Data were retrospectively extracted from the routine hospital

information systems and comprised the date and time of

arrival in the A&E department, the time seen by a doctor

(known as treatment time), the time of finishing the episode

(known as conclusion time), the time of departure and the

triage category allocated to the patient. These data were

collected for all patients attending the A&E department

during the 10 week study periodthat is, for five weeks before

the institution of the separate stream and for five weeks after.

Data validation comprised checking for missing data, correlating data items and checking for outliers (or negative) waiting

times. Excessive or invalid waiting times were double checked

against manual records. Waiting time was defined as the time

from arrival to time of seeing the doctor in minutes. Where the

time of first seeing the doctor was missing, but the time of

finishing the episode was available (for example, cases where

no treatment was given), waiting time was defined as the time

from arrival to finishing the episode. Cases were defined as

spoiled if waiting time could not be calculated from the computerised or manual records.

Data were transferred to SPSS for the purpose of analysis.

Statistical analyses comprised tests of association and the 2

test for linear trend. The 95% confidence intervals were calculated and a critical ratio (Z) test on the difference between two

independent proportions calculated, given the proportion

(expressed as a percentage) and sample size in each sample, in

EpiCalc 2000 Version 1.02.8

RESULTS

A total of 13 918 new patients were seen during the 10 week

study period; 7117 (51.1%) in the first five week period and

6801 (49.9%) in the second five week period when the

separate stream was operational. Time to seeing a doctor was

missing for 1148 cases (8.2%), ranging from 9.0% in the first

five week period to 7.4% in the second five week period

(2(1df)=12.33, p<0.001). Altogether 162 (1.2%) cases were

identified as having excessive or invalid waiting times and the

notes were found and checked for all but six of these cases.

Waiting time was available for 13 861 (99.6%) of patients. A

total of 57 cases had incomplete data relating to waiting time;

ranging by week from 0.1% to 0.9% (table 1); 31 (0.4%)

patients in the first time period and 26 (0.4%) patients in the

second time period. 312 (2.2%) cases had incomplete data

relating to triage category.

The recorded time to see a doctor ranged from 0 to 850

minutes (mode 10 minutes, median 36 minutes, SD= 44.52,

28.9%

27.0%

29.3%

32.1%

29.7%

26.7%

34.8%

30.0%

36.4%

32.6%

Table 2

Total

42.6%

36.2%

31.7%

37.2%

26.9%

15.9%

20.9%

28.9%

23.4%

29.0%

1377

1384

1453

1432

1471

1298

1384

1485

1392

1242

13918

100.0%

1.00

0.46

0.60

0.83

0.67

0.83

Triage category

Triage category

Immediate

See within

See within

See within

See within

Total

Missing

Total

Relative risk of

waiting >60 min

10 min

60 min

120 min

240 min

1

2

3

4

5

Frequency

37

254

5260

7886

169

13606

312

13918

0.3

1.9

38.7

58.0

1.2

100.0

2.2

interquartile range, 5th and 95th percentile values: 5133

minutes). Comparison of the two five week periods demonstrated that the proportion of patients waiting less than 30

minutes improved from 35.4% (n=2517) to 44.0% (n=2979)

(2(1df)=103.34, p<0.0001). Similarly, the proportion waiting

less than 60 minutes increased from 65.1% (n=4610) to 76.2%

(n=5164) (2(1df)=207.6, p<0.0001). Using data for the first

five week period as the standard, the relative risk of waiting

over one hour is shown for each subsequent week (table 1).

During the first week that the separate stream was introduced,

the relative risk of waiting for more than one hour fell by 54%.

In the following four weeks, the relative risk of waiting more

than one hour fell by 32%.

Triage category was available for 13 606 (97.8%) patients

and only 2.1% of these received a triage category of 1 or 2

(table 2). No difference in the proportion of patients seen

within the target time was noted for triage categories 1, 2 or 5

(table 3). Statistically significant improvements in the

proportion of patients seen within the target time were

observed for triage categories 3 and 4.

LIMITATIONS

The unit studied only sees trauma patients and a separate unit

in the city sees medical, paediatric, and surgical emergencies.

This has implications for the generalisability of these results as

medical cases are likely to take longer to treat and are usually

more serious. Some people do, however, self present with nontrauma cases to this centre. It is not likely that the reduced

waiting times observed relate only to those patients who

would more appropriately attend a GP walk in centre as a previous audit, undertaken in the department, has demonstrated

that less than 5% of patients are suitable for care by general

practitioners. Nevertheless a system is now in place to refer

such patients to the out of hours centre.

Data relating to the time seen by a doctor were missing from

the computerised records in 1148 cases (9.2%). The proportion

of cases missing varied between the two time periods and was

www.emjonline.com

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 6, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

30

Cooke, Wilson, Pearson

Table 3

Percentage of patients seen within target time by triage category

Before separate stream started

After separate stream started*

Triage category

% (95% CI)

% (95% CI)

1

2

3

4

5

11

48

2012

3442

98

52.4

41.0

72.8

87.6

96.1

9

36

1576

3022

44

56.3 (30.6 to 79.28)

32.1 (23.8 to 41.7)

78.6 (76.7 to 80.4)

94.1 (93.2 to 94.9)

100.0 (90.0 to 100.0)

0.01

1.26

4.55

9.29

0.77

0.46

0.10

<0.0001

<0.0001

0.22

Immediate

<10 min

<60 min

<120 min

<240 min

(30.4

(32.1

(71.1

(86.5

(89.7

to

to

to

to

to

73.6)

50.5)

74.4)

88.6)

98.8)

*Data have been used for the four week period where the only intervention was the introduction of the

separate stream system (that is, 8 June to 6 July); critical ratio (Z) test and one sided p value.

greater (9.0%) in the first five week period than in the second

five week period (7.4%). Using the time of finishing the

episode to calculate waiting time for those cases where time

seen by a doctor was missing, may marginally inflate our estimates of waiting time. Given the uneven distribution of missing values this could have a greater effect in the first five week

period.

The first week, starting 1 June 1999, during which the new

separate stream for minor injuries was introduced, was also

associated with a greater number of hours of consultant presence within the A&E department. The consultants were not

only seeing patients as per normal practice but also ensuring

that the new system was adhered to and used at all times

required. In the following weeks (week starting 8 June 1999

onwards) the only intervention under assessment was the

new separate stream system.

shown to be equal to that of junior doctors.11 Such a system is

now routinely used in University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire whenever the waiting time exceeds one hour. The

use of a dedicated nurse to undertake treatment for this

stream of patients has now also been introduced. This study

did not investigate the use of trigger points to determine when

separate streams should be used. In this study, separate stream

use was undertaken at all times when there was a wait to see

a doctor and there were more than three doctors on duty. Further work is required to determine the most appropriate times

for operating a separate stream system.

DISCUSSION

Funding: none.

This study shows that introduction of a separate stream for

minor injuries can produce an improvement in the number of

trauma patients waiting over an hour by about 30%. If this is

associated with an increase in consultant presence on the shop

floor it may be possible to achieve a 50% decrease. The greater

decrease in patients waiting times that was observed when a

consultant was present may be related to several factors such

as an extra pair of hands, greater adherence to and use of the

new system and less wasted time by other staff because there

was a senior watching over them.

It has been suggested previously that although separate

stream systems may result in patients being seen more

quickly, this could be at the expense of those with more urgent

needs (triage categories 1, 2 and 3). However, we have demonstrated that this is not the case and statistically significant

improvements in the proportions of patients seen within target times are demonstrated for patients in triage categories 3

and 4. These improvements have been achieved with no

increase in the number of medical or nursing staff. This study

used a cubicle within the present A&E department area. Use of

a separate area to see minor injuries may however require

extra staff.

Data were not collected concerning either patient or staff

satisfaction with the separate stream system. The effect of a

separate stream on satisfaction should be considered by future

studies, however, as one of the commonest sources of

complaint in A&E is the waiting time9 10 it seems probable that

a substantial improvement in waiting times will be associated

with improved patient satisfaction.

We recommend that departments use a separate stream for

minor injuries to decrease the number of patients enduring

long waits in the A&E department. This separate stream could

be run equally well by nurse practitioners, as care has been

www.emjonline.com

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Particular thanks are due to Andrew Heyes of University Hospitals

Coventry and Warwickshire IT Department for downloading the data

and Pam Bridge, Department of Primary Care and General Practice,

University of Birmingham for her help and support.

Conflicts of interest: none.

.....................

Authors affiliations

M W Cooke, Centre for Primary Health Care Studies, University of

Warwick, Coventry, UK

S Wilson, Department of Primary Care and General Practice, Division of

Primary Care Public and Occupational Health, University of Birmingham,

UK

S Pearson, New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton, UK

REFERENCES

1 Anonymous. A&E modernisation programme: interim report to ministers.

London: Department of Health, 1999.

2 Cooke MW, Higgins J, Bridge P. A&E. The present state. Emergency

Medicine Research Group, University of Warwick, 2000.

(http://www.emerg-uk.com/reports.htm).

3 Ranjadayalan K, Umachandran V, Timmis AD, et al. Fast track

admission for acute myocardial infarction. BMJ 1992;304:3801.

4 Ryan J, Ghani M, Staniforth P, et al. Fast tracking patients with a

proximal femoral fracture. J Accid Emerg Med 1996;13:10810.

5 Hampers LC, Cha S, Gutglass DJ, et al. Fast track and the pediatric

emergency department: resource utilization and patients outcomes. Acad

Emerg Med 1999;6:11539.

6 Lau FL, Leung KP. Waiting time in an urban accident and emergency

departmenta way to improve it? J Accid Emerg Med

1997;14:299301.

7 Meislin HW, Coates SA, Cyr J, et al. Fast Track: urgent care within a

teaching hospital emergency department: can it work? Ann Emerg Med

1988;17:4536.

8 Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd edn.

Chichester: Wiley, 1981:234.

9 Burstein J, Fleisher GR. Complaints and compliments in the pediatric

emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 1991;7:13840.

10 Hunt MT, Glucksman ME. A review of 7 years of complaints in an

inner-city accident and emergency department. Arch Emerg Med

1991;8:1723.

11 Sakr M, Angus J, Perrin J, et al. Care of minor injuries by emergency

nurse practitioners or junior doctors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet

1999;354:13216.

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 6, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

The effect of a separate stream for minor

injuries on accident and emergency

department waiting times

M W Cooke, S Wilson and S Pearson

Emerg Med J 2002 19: 28-30

doi: 10.1136/emj.19.1.28

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://emj.bmj.com/content/19/1/28.full.html

These include:

References

This article cites 8 articles, 2 of which can be accessed free at:

http://emj.bmj.com/content/19/1/28.full.html#ref-list-1

Article cited in:

http://emj.bmj.com/content/19/1/28.full.html#related-urls

Email alerting

service

Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the

box at the top right corner of the online article.

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

Вам также может понравиться

- Asepsis and Infection ControlДокумент15 страницAsepsis and Infection ControlhannahОценок пока нет

- Nasogastric TubeДокумент3 страницыNasogastric TubeCharm TanyaОценок пока нет

- CH 16Документ7 страницCH 16hannahОценок пока нет

- General Signs & Symptoms of Medical Emergencies:: FaintingДокумент6 страницGeneral Signs & Symptoms of Medical Emergencies:: FaintinghannahОценок пока нет

- JournalДокумент5 страницJournalhannahОценок пока нет

- To Be DeletedДокумент4 страницыTo Be DeletedhannahОценок пока нет

- Professional Adjustment Final 2Документ41 страницаProfessional Adjustment Final 2lielani_martinezОценок пока нет

- JRV 130007Документ12 страницJRV 130007hannahОценок пока нет

- Nephro NCP1Документ3 страницыNephro NCP1hannahОценок пока нет

- Case Pres Palia CombineДокумент6 страницCase Pres Palia CombinehannahОценок пока нет

- Euthanasia BriefingДокумент3 страницыEuthanasia BriefingRafael CancinoОценок пока нет

- o o o - o o o - o o - : Legal Issues United States LawДокумент8 страницo o o - o o o - o o - : Legal Issues United States LawhannahОценок пока нет

- Nephro NCP2Документ2 страницыNephro NCP2hannahОценок пока нет

- Patients Profile:: History of Present IllnessДокумент2 страницыPatients Profile:: History of Present IllnesshannahОценок пока нет

- SVR Values Before and After TherapyДокумент2 страницыSVR Values Before and After TherapyCharm TanyaОценок пока нет

- PT Profile CasepresДокумент2 страницыPT Profile CasepreshannahОценок пока нет

- Common Causes of Heart FailureДокумент3 страницыCommon Causes of Heart FailurehannahОценок пока нет

- For Case AnalysisДокумент2 страницыFor Case AnalysishannahОценок пока нет

- ARDS Sign and Symptoms Et. Factors and DiagnosticsДокумент2 страницыARDS Sign and Symptoms Et. Factors and DiagnosticshannahОценок пока нет

- Determinants and Control of Cardiac OutputДокумент2 страницыDeterminants and Control of Cardiac OutputhannahОценок пока нет

- Case Pres Surg WarddfgДокумент6 страницCase Pres Surg WarddfghannahОценок пока нет

- Ineffective Cerebral Tissue Perfusion Related ToДокумент7 страницIneffective Cerebral Tissue Perfusion Related TohannahОценок пока нет

- NCP For Cervical SpondylosisДокумент3 страницыNCP For Cervical Spondylosishannah0% (1)

- Problem 1Документ10 страницProblem 1BeverlyОценок пока нет

- RulesДокумент30 страницRulesCharm TanyaОценок пока нет

- InterventionsДокумент3 страницыInterventionsCharm TanyaОценок пока нет

- Garbage Eating Up City FundДокумент2 страницыGarbage Eating Up City FundhannahОценок пока нет

- Reference1 TolДокумент2 страницыReference1 TolhannahОценок пока нет

- ReferencesДокумент3 страницыReferenceshannahОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- NRF Nano EthicsДокумент18 страницNRF Nano Ethicsfelipe de jesus juarez torresОценок пока нет

- "Next Friend" and "Guardian Ad Litem" - Difference BetweenДокумент1 страница"Next Friend" and "Guardian Ad Litem" - Difference BetweenTeh Hong Xhe100% (2)

- Management of Preterm LaborДокумент2 страницыManagement of Preterm LaborpolygoneОценок пока нет

- SanMilan Inigo Cycling Physiology and Physiological TestingДокумент67 страницSanMilan Inigo Cycling Physiology and Physiological Testingjesus.clemente.90Оценок пока нет

- Jeremy A. Greene-Prescribing by Numbers - Drugs and The Definition of Disease-The Johns Hopkins University Press (2006) PDFДокумент337 страницJeremy A. Greene-Prescribing by Numbers - Drugs and The Definition of Disease-The Johns Hopkins University Press (2006) PDFBruno de CastroОценок пока нет

- PMI Framework Processes PresentationДокумент17 страницPMI Framework Processes PresentationAakash BhatiaОценок пока нет

- Bedwetting TCMДокумент5 страницBedwetting TCMRichonyouОценок пока нет

- Village Survey Form For Project Gaon-Setu (Village Questionnaire)Документ4 страницыVillage Survey Form For Project Gaon-Setu (Village Questionnaire)Yash Kotadiya100% (2)

- Comprehensive Safe Hospital FrameworkДокумент12 страницComprehensive Safe Hospital FrameworkEbby OktaviaОценок пока нет

- Paper Specific Instructions:: GATE Chemical Engineering MSQ Paper - 1Документ11 страницPaper Specific Instructions:: GATE Chemical Engineering MSQ Paper - 1Mayank ShelarОценок пока нет

- Task 5 Banksia-SD-SE-T1-Hazard-Report-Form-Template-V1.0-ID-200278Документ5 страницTask 5 Banksia-SD-SE-T1-Hazard-Report-Form-Template-V1.0-ID-200278Samir Mosquera-PalominoОценок пока нет

- Soalan 9 LainДокумент15 страницSoalan 9 LainMelor DihatiОценок пока нет

- Sop For Enlistment of Engineering ConsultantsДокумент1 страницаSop For Enlistment of Engineering Consultantssatheb319429Оценок пока нет

- The Vapour Compression Cycle (Sample Problems)Документ3 страницыThe Vapour Compression Cycle (Sample Problems)allovid33% (3)

- Nta855 C400 D6 PDFДокумент110 страницNta855 C400 D6 PDFIsmael Grünhäuser100% (4)

- Pay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountДокумент1 страницаPay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountVee-kay Vicky KatekaniОценок пока нет

- Engineering Project ListДокумент25 страницEngineering Project ListSyed ShaОценок пока нет

- 7 UpДокумент3 страницы7 UpRajeev TripathiОценок пока нет

- Viscoline Annular UnitДокумент4 страницыViscoline Annular UnitjoquispeОценок пока нет

- Pantera 900Документ3 страницыPantera 900Tuan Pham AnhОценок пока нет

- Leather & Polymer - Lec01.2k11Документ11 страницLeather & Polymer - Lec01.2k11Anik AlamОценок пока нет

- University of Puerto Rico at PonceДокумент16 страницUniversity of Puerto Rico at Ponceapi-583167359Оценок пока нет

- Border Collie Training GuidelinesДокумент12 страницBorder Collie Training GuidelinespsmanasseОценок пока нет

- Entitlement Cure SampleДокумент34 страницыEntitlement Cure SampleZondervan100% (1)

- Maxillofacial Notes DR - Mahmoud RamadanДокумент83 страницыMaxillofacial Notes DR - Mahmoud Ramadanaziz200775% (4)

- Reading Practice 6Документ5 страницReading Practice 6Âu DươngОценок пока нет

- انظمة انذار الحريقДокумент78 страницانظمة انذار الحريقAhmed AliОценок пока нет

- DT 2107Документ1 страницаDT 2107Richard PeriyanayagamОценок пока нет

- Home Composting SystemsДокумент8 страницHome Composting Systemssumanenthiran123Оценок пока нет

- DPA Fact Sheet Women Prison and Drug War Jan2015 PDFДокумент2 страницыDPA Fact Sheet Women Prison and Drug War Jan2015 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgОценок пока нет