Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

John Markoff - Where and When Was Democracy Invented?

Загружено:

Miodrag MijatovicОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

John Markoff - Where and When Was Democracy Invented?

Загружено:

Miodrag MijatovicАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

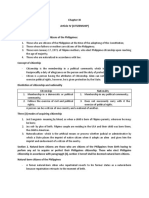

Society for Comparative Studies in Society and History

Where and When Was Democracy Invented?

Author(s): John Markoff

Source: Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 41, No. 4 (Oct., 1999), pp. 660-690

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/179425 .

Accessed: 01/08/2013 01:09

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press and Society for Comparative Studies in Society and History are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Comparative Studies in Society and History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Where and When Was Democracy

Invented?l

JOHN MARKOFF

Universityof Pittsburgh

INTRODUCTION

BarringtonMoore's Social Origins of Dictatorshipand Democracy made explicit an influentialbutusuallyunstatedprinciplefor comparativepolitical sociology. In his searchfor the social sourcesof differentsortsof political systems,

Moore devoted chaptersto revolutionaryor quasi-revolutionaryupheavalsin

England,France,the United States, Japan,China, and India.He did not feel it

equallyimportantto considerthe historyof democracyin Scandinavia,the Low

Countries,or Switzerland(not to mention Canada,Australia,and New Zealand). The lesser players on the world stage, buffeted by the prestigious ideologies of the greaterplayers,tied to the latter'seconomies and sometimes assaultedby their armies,are less rewardingas researchsites for comparativists

looking for distinct national"cases"to test their ideas. Small, weaker powers

are not, in this reasoning, independentcases of anything. One presumes the

same logic led Moore to include only thirdworld giants like China and India

and not the many othercountriesof Asia, Africa, and LatinAmerica. Characteristically,it is GermanyandRussiathatMooreregardsas the most significant

cases of democraticfailureomittedfrom his study:not Spain or Italy,let alone

Bolivia or Burma.2In manya theoryof "moderization,"England-or England

and France-have been taken as prototypes or paradigmaticcases, and the

broadoutlinesof theirhistoriesarethereforefar morelikely to have enteredthe

educationof Americansociologists thanthe historiesof otherplaces in Europe

or beyond. Sometimesthe presumedcentralityof one or more of these cases is

made explicit, sometimes not.

The "greatpower" perspective on world history has its uses-more weak

For comments on an earlierdraftand other suggestions I thankHermannGiliomee, Michael

Hanagan,JuanLinz, Ver6nicaMontecinos,Dora Orlansky,Rudolf Rizman,RichardRose, Lionel

Rothkrug,ArthurStinchcombe,CharlesTilly, and SashaWeitman.A fellowship from the University Centerfor InternationalStudiesof the Universityof Pittsburghis also gratefullyacknowledged.

2 BarringtonMoore, Jr.,Social Origins of Dictatorshipand Democracy:Lord and Peasant in

the Making of the Modern World(Boston: Beacon Press, 1966), pp. xi-xiii. Moore went on to

tackle the missing Germancase in Injustice: The Social Bases of Obedience and Revolt (White

Plains, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1978) and, more briefly,the Russianin Authorityand InequalityUnder

Capitalismand Socialism (Oxford:ClarendonPress, 1987).

0010-4175/99/4301-3446$7.50 + .10 ? 1999SocietyforComparative

Studyof SocietyandHistory

66o

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE

AND

WHEN

WAS DEMOCRACY

INVENTED?

66I

powers sneeze when the U.S. catches cold than the reverse-but it also obscures much of the dynamicebb and flow of social processes across frontiers.

Not everythinghappenedfirstin a greatpower.Nor arethe greatpowers always

usefully thoughtof as independentcases.

If we move beyond comparativehistory as conventionally conceived-as

the studyof similaritiesand differencesamongthe historicaltrajectoriesof different places-to the study of complexly interactivetransnationalsystems, it

would be an errorto assumethatinnovationsinvariablydiffuse from a creative

great power to weaker players who seek to curryfavor, who are intellectually

enchantedby powerfulmodels of success, or upon whom the powerfulcan impose theirinstitutionsby force. Of course,these pathsof diffusionfromstronger

to weakerstateshave been exemplified many times. No one would write a history of democracywithoutnoting the impactof the Frencharmiesin the 1790s

or the Americanarmiesin the 1940s. But the patternof innovationand diffusion may often be far more complex.

In this essay I will be looking at the times and places when innovationsin

democracywere pioneered.Democracy could be defined in 1690 as a "Form

of governmentin which the people have all authority,"3a definitionas succinct

as it is imprecise. In the subsequentage of democraticbreakthrough(and still

today) the challenge was (and is) the creationof concreteinstitutionsthatrealize such a notion. But what institutions?If we look over the historyof modem

democracy,we will find thatthose who called themselves democratsat the tail

end of the eighteenthcenturywere likely to be very suspiciousof parliaments,

downrighthostile to competitivepolitical parties,criticalof secret ballots, uninterested or even opposed to women's suffrage, and sometimes tolerant of

slavery.The claim thatsome institutionsand not othersare modes for realizing

democracyis a very powerfulone; but whatthose institutionsarehas been subject to considerablechange.

Any discussion of the loci of democraticbreakthroughsmust acknowledge

ambiguityandlimitedknowledge,the formercompoundingthe latter.Such ambiguity is inherentin any searchfor origins within an ongoing historicalflow,

in which thereare always precursorsand prototypes,as well as interestingoffshoots thatwent somewhereelse. In addition,we have abortedand interrupted

developments.France,for example, was early to enact universalmale suffrage,

but laterretractedit.

To keep the subject from overflowing even a long essay, some boundaries

need to be set. We focus on the nationalstate here, ratherthan subnationalor

supranationalinstitutions;however,we cannotaltogetherignorethe distinction

between local and national government,which are not always organizedthe

same way, to put it mildly.We can find instanceswhere significantdemocratic

practiceat the nationallevel coexists with widespreadvillage despotisms(as in

3 Antoine Furetiere,Dictionnaireuniversel(Geneva:SlatkineReprints,1970 [1690]), v. 1.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

662

JOHN

MARKOFF

contemporaryIndia);we can find-particularly in the world before the eighteenthcentury-semidemocratic assembliesat the village level coexisting with

traditionalforms of sacralizedmonarchyand aristocraticrule4 at the national

level (a widespreadexperiencein many partsof the world).In federalsystems,

rights at state and nationallevels may differ-a significant matterin the democratichistoriesof Australia,the UnitedStatesandSwitzerland;they may differ among the states as well, as seen, for example, in the removalof genderrestrictionson voting in the United States.As for the temporalboundariesof this

essay, I take my startingpoint as the 1780s, for reasonsthatwill be made clear

below.5

One last ambiguityremains:the law may be a breakthrough,but what of actual practice?Wherethereis a substantialgulf betweenthe "legalcountry"and

the "realcountry,"to use a distinctionwell-knownin nineteenth-centuryFrance

and contemporaryLatinAmerica,it may be very misleadingto look at the date

of enactmentof some new law as the only indicatorof electoralprocedure,parliamentarypractice,or voting rights.The law is partof reality,but a researcher

could seriouslyerrto take it as the entirereality.6But thereis also just plain ignorance-much of the worldhistoryof democracyseems to me effectively unknown. If I've slighted a democraticinnovationhere or exaggeratedthe living

reality of an innovationthathad no actualitybeyond an unenforcedlaw there,

let the brickbatsfly. And where the history is shroudedin darkness,may some

hardyresearchershed some light.

In an essay discussing something whose meaning has historically been so

contested-and altered-as democracy,7I shouldmakeclearthatI planto look

at the initialbreakthroughsin the institutionalizationof democracyas thatterm

is rathergenerallydeployedin the late 1990s. Democracyis used, for now, primarily to mean a set of political proceduresin which the holders of power are

responsibleto electorates,either directly (by virtue of being elected) or indirectly (by virtue of being appointedby the elected); in which almost all adult

citizens can vote (while noncitizens,nonadults,and small numbersof criminal

4 Steven Muhlbergerand Phil Paine, "Democracy'sPlace in WorldHistory,"Journal of World

History 4, 1993, pp. 23-45; for much detail on France, see Henry Babeau, Les Assembldes

generales des communautesd'habitantsen France du XIIIesiecle a la Rdvolution(Paris:Rousseau,

1893) andAlbertBabeau,Le Villagesous l'Ancien Regime(Paris:Perrin,1915).

5 Importantearlierinnovationsin the developmentof representativeinstitutionsthatcould bargain on the taxpayers'behalf with those who controlledorganizedviolence will not be considered

here; nor will earlierinnovationsin the developmentof electoralpractices,secularrulership,state

controlof militaryforce, bureaucratic/administrative

capacitiesof governmentsto enforcepolicies,

and citizenshiprights.

6 Even the act of dating the law is not without its ambiguity.Laws may be enactedat one moment, subjectto some form of ratificationat a laterpoint, and formallygo into force at yet a third

moment;they may then be reinterpretedyears or decades later by courts, or modified by subsequentlegislative action;they may or may not be vigorouslyenforced;and whetherenforcedor not

may be more or less widely flouted. I have thereforetried to base my principalclaims about the

loci of democraticinnovationon broadpatterns,ratherthanon any single episode.

7 See JohnMarkoff,Wavesof Democracy:Social Movementsand Political Change (Thousand

Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 1996)

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE

AND

WHEN

WAS DEMOCRACY

INVENTED?

663

adult citizens do not necessarily have such rights); and in which people can

form partiesto contest elections, campaignsprovide some opportunityfor oppositions to address the electorate, and the official vote counts are not profoundly fraudulent(but in which it is not necessarily the case that all parties

have equal opportunitiesto make theircase, nor thatthe vote counts be totally

honest).

Although political scientists today are generallyreluctantto admit any featuresof social structureinto theirproceduraldefinitionof democracy8-so that

egalitarianand inegalitariansocieties are identically democraticif they both

adhereto such proceduresto the same degree-I would add one conditionthat

I believe is simply takenfor grantedby the many social scientistsof the 1990s,

but would not have been presumedby anyone in the 1790s. This is that residence and citizenship must broadlyoverlap.9Privatelyowned chattel slavery

and the existence of ruralmajoritiessubjectto seigneurialrights are not compatible with "democracy"as generally understoodin the 1990s, regardlessof

how dominantminoritiesor majoritiesgovernthemselvesandtheirdependents.

In other words, in currentnotions of democracylegally enforceablestructures

of servitude,dependence,or deferencethat subordinatelarge numbersof adult

persons do not exist.

Finally a plea for forbearance:so many specific practiceshave become part

of the historyof democracythatno one could documentthem all shortof a very

long book. The bases for exclusion frompoliticalrights,for example,have been

variedenough thatwhat follows is inevitablybut a selection. I pay no attention

here, for example, to exclusions based on religion.

For all the ambiguities,uncertaintiesandinevitableerrorsof dating,I believe

that the following survey shows a basic patternso persistentlythat more evidence and more refined concepts would be unlikely to alter it fundamentally:

for the past two centuriesthe greatinnovationsin the invention of democratic

institutionshave generallynot takenplace in the world's centersof wealth and

power.

The First Democrats

The late eighteenthcentury seems to be the moment when people on several

continentsbegan to speak of democracyas a form of political organizationto

be actively pursued or actively resisted. The word "democracy"had been

known by educatedEuropeans(andAmericans)for a long time before that,to

8 In the editors'

preface to their importantcollection on the democratizationsof the 1980s, for

example, we find LarryDiamond, JuanJ. Linz, and SeymourMartinLipset explaining:"Weuse

the term 'democracy'in this study to signify a political system, separateand apartfrom the economic and social system to which it is joined. Indeed, a distinctiveaspect of our approachis to insist thatissues of so-called economic and social democracybe separatedfrom the questionof governmentalstructure"(Democracy in Developing Countries. v. 4, Latin America [Boulder, CO:

Lynne Rienner, 1989], p. xvi.).

9 On this

point see CharlesTilly, "Democracyis a Lake,"in Roadsfrom Past to Future(Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1997), p. 199.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

664

JOHN

MARKOFF

be sure,as one of the basic types of political systems recognizedby the thinkers

of classical Greece. Indeed, the word was often used to denote an ancientpolitical system as a point of referencewhen discussing a living one10,as in the

observation of a late seventeenth-centurydictionary that "democracy only

flourishedin the republicsof Rome and Athens."1 At othertimes it was used

pejoratively,as a failed system whose invitation to mob violence was to be

avoided.12But it was in that late eighteenth-centurymoment that the form

"democrat"came into use, for thatwas when social movementsbegan to challenge existing social ordersin the nameof democracyandEuropeansandNorth

Americanssaw theircountriesdivided into two camps.13

The terms "democrat"and "aristocrat,"denotingthe partisansof these two

camps,beganto be widely used in revolutionarystrugglesin the Low Countries

duringthe 1780s'4 and were almost at once taken up elsewhere, as those engaged in politicalconflicts found the dichotomyserviceablein theirown struggles. Americanas well as French revolutionaryelites wrestled with the relationship of their own political ideas to democracy,sometimes explaining the

superiorityof a republicto a democracy,sometimes conflatingthe two15;the

Prussian government explained its participationin the dismembermentof

Polandin 1793 by the spreadto thatcountryof "Frenchdemocratism."'6

10 It was

occasionally appliedto existing political systems, particularlysome of the Swiss cantons, but also a numberof self-governing Germancities (Conze and Koselleck, Geschichtliche

Grundbegriffe,pp. 845-47). For a superbdiscussion of one instance,see RandolphC. Head, Early ModernDemocracy in the Grisons: Social Orderand Political Language in a Swiss Mountain

Canton, 1470-1620 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1995).

l Furetiere,Dictionnaireuniversel.

12

Although Furetiereneeded no more than ten lines to define both "democracy"and "democratic"in his dictionaryof 1690, he found the space to informthe readerthat"theworst of all outbursts is a democraticone," and that "seditionsand turmoilhappenoften in Democracies"(Dictionnaireuniversel).

13 The following discussiondrawsheavily on OttoBrunner,WernerConze, andReinhartKoselleck, eds., GeschichtlicheGrundbegriffe:Historisches Lexikonzur politisch-sozialen Sprache in

Deutschland (Stuttgart:Klett Verlag, 1972-84), v. 1, pp. 821-99; RobertPalmer,"Notes on the

Use of the Word 'Democracy', 1789-1799," Political Science Quarterly68, 1953, pp. 203-26;

Pierre Rosanvallon,"The History of the WordDemocracy in France,"Journal of Democracy 6,

1995, pp. 140-54; Horst Dippel, "D6mocratie,Democrates,"in Rolf Reichardtand Eberhard

Schmitt, eds., Handbuchpolitisch-sozialer Grundbegriffein Frankreich1680-1920 (Munich:

Oldenbourg,1986), vol. 6, pp. 57-97; Jens A. Christophersen,The Meaning of "Democracy"as

Used in EuropeanIdeologiesfrom the French to the RussianRevolutions.An Historical Studyof

Political Language(Oslo: Universitetsforlaget,1968).

14 For a slightly earlierisolated use, see Conze and Koselleck, GeschichtlicheGrundbegriffe,

p. 854.

15 Madison held a "republic"better than a "democracy"in 1787 in Federalist No. 10, as did

Jacques-PierreBrissot in 1791. Robespierrein 1794 held that "thesetwo words are synonyms."

See Jacob E. Cooke, ed., The Federalist (Middletown,Conn: Wesleyan University Press, 1961),

pp. 62-5; Brissot in Recueuil de quelques dcrits,principalementextraits du Patriote Francais,

reprintedin Aux origines de la Republique,1789-1792, v. 5: 1791, Naissance du parti rdpublicaine (Paris:EDHIS, 1991), pp. 3-7; Maximilien Robespierre,Oeuvres.v. 10, Discours, 17juillet 1793-27juillet 1794 (Paris:Presses Universitairesde France, 1967), p. 352.

16 KarolLutostariski,Les partages de la Pologne et la luttepour l'inddpendance(Paris:Payot,

1918), p. 113.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE

AND

WHEN

WAS DEMOCRACY

INVENTED?

665

By the late 1790s, such usages were well-known and widespread.In 1797, a

future pope's Christmashomily claimed the compatibilityof democracy and

the Gospels.17But, althoughsuch termshad become widely current,it was far

easierto know whata "democrat"was-an anti-aristocrat-than what"democracy"was.18"Aristocrats"could be identifiedwith the defense of legally sanctioned structuresof birth-basedprivilege, a hierarchicalandcorporatesocial order, sacralizedmonarchyand an establishedchurch.But it was much harderto

specify the new institutionsthat democratswished to create; and many who

challenged hierarchical, corporate, royal, and sacred institutions distanced

themselves from the term "democracy."If aristocracywas identified with familiarinstitutions,the institutionsof democracywere to be invented.The power of the broadnotion of democracywas much greaterthan any consensus on

what precisely was being advocated.Democratshave debatedthe institutions

needed for democracyever since.

TWO HUNDRED

YEARS

OF DEMOCRATIZATION

The Writingof Constitutions

In their struggles against arbitraryacts of monarchicalauthority,eighteenthcentury opposition movements in Europe and North America often rallied

aroundthe notion of a constitution;constitutionalists,however, were themselves deeply dividedbetweentwo conceptionsof the constitutionalidea. Some

had in mind a combinationof fundamentallaws, customarypractices,understandingsof the divine plan, and common sense thatcould be invoked in criticism of arbitrarymonarchs and their tyrannicalministers:the restorationof

properrespect for a polity's traditionswas needed. Othersdid not clamor for

the restorationof the existing constitution,but for the draftingof new, explicit

rules for political life-rules thatwould have to be broughtinto existence. Setting these rules down in writtenform, throughthe attendantprocesses of debate, revision, adoption, and promulgation,became a powerful foundational

act. By making the fundamentallaws of the political orderthe outcome of deliberateactions by living people, the writingof a constitutionbecame a powerful statementsituating the fount of authorityin human wishes. Such written

statements,deliberatelysetting forth the organizationof governmentand the

powers of its principalcomponents, also had the potential, if effectively followed, to providebarriersto arbitraryauthority.

That constitution-writingwas in the air in the late eighteenth century is

shown by such prototypes as the document issued by Sweden's Gustav III,

which aimed for popularsupportagainstthe nobility througha formal clarifi17 Palmer,DemocraticRevolution,v. 1, 18.

p.

18 A dictionaryof 1792 defines "democrat"as "one of the revolutionarywords thathas had the

greatestsuccess. It means the subjectof a democraticgovernmentand someone who, by principle

and by fashion, is a partisanof democracy."See Max Frey, Les Transformationsdu vocabulaire

francaise a l'epoque de la Revolution(1789-1800) (Paris:PressesUniversitairesde France,1925),

p. 139.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

666

JOHN MARKOFF

cation of the powers of monarchand parliament19;wartime constitutionsin

Britain'srebellingAmericancolonies20; andthe text proposedby Utrecht'sPatriots in 1784.21But it was the new United States that was celebratedas the

great pioneer in this regardwhen its Articles of Confederationwere replaced

by a more enduringconstitution(ratifiedin 1789), whose clear provisions for

amendment-immediately utilized to add on the Bill of Rights-further amplified the model of a fundamentaldocument,writtenand correctableby humanhands.This sense was all the morestrengthenedby the openingwords"We

the People,"which made a very differentclaim thana royal declaration,just as

a specifically empowered constitutionalconvention and a ratificationprocedurefurtherenhancedthe element of humandebate,reflection,and decision.22

The first European state to follow suit was Poland, whose constitution of

1791,23in announcingthatthe King ruled"by the grace of God and the will of

the nation,"24suggesteda divine as well as a humansourceof authority.25This

documentwas soon renderedinoperativeby the occupying armies of Russia,

19 Sweden's 1772 constitutionwas a

developmentin an alreadyestablishedtradition.In 1720

Sweden's parliamentadoptedthe first of severalfundamentaldocumentsthatdefined the structure

of centralauthority,writinga constitutionfor which Montesquieu,Rousseau,andMably professed

admiration.See MichaelRoberts,TheAge ofLiberty:Sweden,1719-1772 (Cambridge:Cambridge

University Press, 1986); H. Arnold Barton, Scandinavia in the RevolutionaryEra, 1760-1815

(Minneapolis:University of MinnesotaPress, 1986), and "GustavIII of Sweden and the Enlightenment",EighteenthCenturyStudies6, 1972-73, p. 8.

20 Wood, The Creationof theAmerican Republic,

pp. 127-61.

21 Simon

Schama, Patriots and Liberators:Revolutionin the Netherlands,1780-1813 (New

York:RandomHouse, 1977), 1776-1787 (New York:Norton, 1972), pp. 88-89.

22 A "convention"was a centuries-old

English termfor a meeting outside (and sometimes opposed to) established institutions;the phrase "nationalconvention"seems to be an Irish radical

coinage of 1783. See GordonS. Wood,TheCreationof theAmericanRepublic,pp. 310-12; Palmer,

TheAge of the DemocraticRevolution,vol., 1, p. 303; RobertB. McDowell, Irelandin the Age of

Imperialismand Revolution,1760-1830 (Oxford:ClarendonPress, 1979), pp. 302-11.

23 The

May 3, 1791 documentsuggests revisabilityby sometimesusing the work "constitution"

to referto a collection of documentsbeyond itself, some alreadywritten,some yet to be. See Janusz

Duzinkiewicz, Fateful Transformation:The Four Years'Parliamentand the Constitutionof May

3, 1791. East EuropeanMonographsno. 367 (New York:ColumbiaUniversity Press, 1995), pp.

40-54.

24 Elsewhere,the May 3 documentstatesthat"all power in civil society shouldbe derivedfrom

the will of the people" (art.5). See New Constitutionof the Governmentof Poland Establishedby

the Revolutionof the Thirdof May 1791 (London:J. Debrett, 1791), pp. 3, 12. The same ambiguity is found in France'sDeclarationof the Rights of Man and Citizen, whose Article 3 has it that

"the principleof all sovereigntyresides essentially in the nation,"after having describeditself as

being declared"in the presenceand underthe auspices of the SupremeBeing" (Duverger,Constitutions et documentspolitiques, p.3). An importantecho of the Polish formulationis found in the

1824 constitutionof newly independentbut still monarchicalBrazil, in which Dom Pedro's authorityexists "by the grace of God and the unanimousacclamationof the peoples."The would-be

emperorof independentMexico in the 1820s reigned,so the official formulahadit, "bydivineprovidence and the congress of the nation."See Constituodopolitica do impdriodo Brasil (Rio de

Janeiro:Silva Porto, 1824), p. 3; TimothyE. Anna, TheMexicanEmpireof Iturbide(Lincoln,NE:

Universityof NebraskaPress, 1990), p. 76.

25 This ambiguitywas retainedin the manysubsequentconstitutionsthatbalancean explicit humanderivationof authoritywith a sacredsourceas well. See JohnMarkoffandDaniel Regan, "Religion, the StateandPoliticalLegitimacyin theWorld'sConstitutions,"pp. 161- 82 in ThomasRobbins and Roland Robertson, eds., Church-State Relations: Tensions and Transitions (New

Brunswick,NJ: TransactionBooks, 1987).

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE

AND

WHEN

WAS DEMOCRACY

INVENTED?

667

Prussiaand Austria.The Polish document,moreover,presentsitself as a royal

enactmenteven as it embodies claims of popularsovereignty.It may well be

that the new United States and the old Polish Republic were the pioneers, successful and unsuccessful,because the notionsof social contractso dearto those

who urgeda constitutionhad a particularlyvivid realityin bothplaces:the United States had well-developed representativemechanismsin its local meetings

and colonial assemblies; the Polish nobility not only exercised considerable

governing functions in the fifty-odd local parliaments,but literally drew up a

new social contract(the pacta conventa) with each king they chose by election.26It was not in the northwestEuropeancore that constitutionswere first

written, but on the western and eastern fringes27(although the French soon

pushed the notion of popular sovereignty further still by having a national

plebiscite on theirconstitutionof 1793).28

In Europe,revolutionaryFranceassumeda majorrole in diffusing constitutionalism furtherafield, not only by markingits own changes of regime with

new constitutions(in 1791, 1793, 1795, 1799, 1802 and 1804) but by inspiring

and compelling similar documentsto be adoptedin the satellite states that its

armiesoverranin the 1790s andbeyond,29sometimesthusreinforcingalreadypresentconstitutionwriting propensities.Other states, trying to resist French

dominance,followed suit. Haiti markedits independencefrom Frenchrule by

enactingits own constitutionin 1805, becoming the second New Worldstateto

do so.30Pressedby Frenchforces, the besieged remnantsof a Spanishgovernment convened an assembly thatissued a constitutionin 1812, partlymodeled

on the Frenchconstitutionsof 1793 and 1795. The Cadiz Constitutionbecame

an importantmodel for the predominantlyrepublicansentimentsof the leadership in the newly independentcountriesof SpanishAmerica duringthe early

nineteenthcentury,who markedthe founding of their own independentstates

with constitutionaltexts.31

26 The literatureon the U.S. constitutionis vast beyond citation;for one work, see GordonS.

Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1993). On Polish institutions see Norman Davies, God's Playground: A HistoTr of Poland (New York: Columbia Univer-

sity Press, 1982), vol. 1.

27 If we stretchour time frameback a bit, we would tip this picturetowardsthe northeastwith

Sweden's constitutionof 1772.

28 Ren6 Baticle, "Le plebiscite sur la Constitutionde 1793",Revolutionfrancaise 57, 1909, pp.

496-524; 58, 1910, pp. 5-30, 117-55, 193-237, 327-41, 385-410.

29 Duverger, Constitutionset documents

politiques; H.B. Hill, "L'influencefranqaisesur les

constitutionsde l'Europe(1795-1799)", La Revolution francaise, 1936-37, pp. 352-63; 154-66.

On revolutionaryDutchconstitutionalismin the 1780s, see WayneP.te Brake,Regentsand Rebels:

The Revolutionary World of an Eighteenth-Century, Dutch City (Oxford: Blackwell, 1989).

30 David Nicholls, FromDessalines to Duvalier (London:Macmillan, 1988), p. 36.

31 With two western

hemisphericprecedentsbehindthem, two SpanishAmericanconstitutions

of 1811 precededthe Spanishdocument(Colombia,Venezuela).The Cadiz constitutionwas a significant model, not just in SpanishAmerica, but in Italy and Norway. See WilliamW. Pierson and

Federico G. Gil, Governmentsof Latin America (New York:McGraw-Hill, 1957), pp. 107-33;

Timothy E. Anna, Spain and the Loss of America (Lincoln, NE: University of NebraskaPress,

1983); Isabel Arriazu,CristinaDiz-Lois, CristinaTorra,and WarrenM. Diem, Estudios sobre las

cortes de Cddiz(Pamplona:EditorialG6mez, 1967);JorgeMarioGarciaLaguardia,CarlosMelen-

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

668

JOHN MARKOFF

By the time the conservativeforces had triumphedin Europe,the model of

constitution-makinghad been firmly implanted in two hemispheres. The

French defeat sparkeda wave of constitutionwriting in the Germanstates.32

Even the restoredFrenchmonarchyitself issued a constitutionin 1814, granted, so its royal preambletells us, in recognition "of the wishes of our subjects."33

Competitive Electoral Parties

Political groupings for the purpose of contesting elections or pursuing legislative objectives were known wherever there were elected bodies of one sort or

another. Even where such groupings were fairly stable-hardly always the

case-and hence tended to develop collective identities, as in the case of

Britain's Whigs and Tories or Sweden's Caps and Hats34, a sense of illegitimacy hung about such their activities.35 Those inclined to the cause of popular

sovereignty often regarded such coalitions as wholly illegitimate, representing

the purely private interest of individual powerholders, of a network of friends

and relations36, or of some other group that differed from and was very likely

antagonistic to the interests of the whole. The very term "party" was largely

used invidiously, for example, during the French Revolution, when the claim

that someone identified with some part of the people was a step short of an accusation of treason. Organized campaigning was scorned, and even declaring

one's own candidacy disapproved.37 British electoral practice was often seen

as a model of corruption, not of order nor of democracy.38 Aspirants to office

dez Chaverri,and MarinaVolio, La Constituci6nde Cddizy su influenciaen Amdrica(San Jose:

CAPEL, 1987);JuanFerrando,La Constituci6nde Espaniolade 1812 en los comienzosdel "Risorgimento"(Rome:InstitutoJuridicoEspafiol, 1959); Antonio Annino, "Pratichecreole e liberalismo

nella crisi dello spazio urbanocoloniale. Il 29 novembre1812 a Cittadel Messico,"QuaderniStorici, Nuova Serie 69 (December) 1988, pp. 727-63; ManuelFerrerMufoz, La Constituci6nde Ca'diz

y su aplicaci6n en la Nueva Espana (Mexico: UniversidadNacionalAut6nomade Mexico, 1993);

T.K. Derry,A Historyof ModernNorway, 1814-1972 (Oxford:ClarendonPress, 1973), p. 9.

32 James J.

Sheehan,GermanHistory, 1770-1866 (Oxford:ClarendonPress, 1989), pp. 41125; Thomas Nipperdey,Germanyfrom Napoleon to Bismarck,1800-1866 (Princeton:Princeton

UniversityPress, 1996), pp. 237-43.

33 "Charteconstitutionellede 4 juin 1814",in Duverger,Constitutionset documentspolitiques,

p. 80.

34 Michael Roberts,Swedishand English Parliamentarismin the EighteenthCentury(Belfast:

The Queen's University, 1973), pp. 24-6.

35 On

eighteenth-centurythinkingaboutpartiesin Britain,see RichardHofstadter,The Idea of

a PartySystem:TheRise of LegitimateOppositionin the UnitedStates, 1780-1840 (Berkeley,CA:

Universityof CaliforniaPress, 1969), pp. 1-39; for a broadsampleof eighteenth-centurywritings,

see J. A. W. Gunn, ed., Factions No More: Attitudesto Party in Governmentand Oppositionin

Eighteenth-CenturyEngland (London:FrankCass, 1972).

36 The designation "Familia"for the faction around the Czartoryskisin eighteenth century

Poland'sparliamentarypolitics is symptomatic.

37 Since such condemnationof electioneeringwas particularlyintense in revolutionaryFrance,

the studyof hiddencandidacyin thatcountryis correspondinglyparticularlyrevealing.See Patrice

Gueniffey, Le nombre et la raison: La Rdvolutionfrancaise et les dlections (Paris: Editions de

l'Ecole des HautesEtudesen Sciences Sociales, 1993), pp. 323-52.

38 Crook, Elections in the French Revolution,pp. 69-70; Gueniffey,Le nombreet la raison,

pp. 315-21.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE

AND

WHEN

WAS DEMOCRACY

INVENTED?

669

might in fact be workingfor theirelection behindthe scenes, giving substance

to the sense of widespreadelectoralcabals.

With the developmentof partiesinhibited-as some gentlemenfound electioneering shameful and some democratsfound election-contestingcoalitions

redolentof aristocraticconspiracy39-the hope of a unitarypopularwill was

enhanced.Democracycould be equatedwith unanimity.Partylegitimation,by

contrast,opened the way to a more pluralisticconceptionof democracy.40

The priorityof unityhad been expressed,for example,by LordBolingbroke,

when he suggested in 1738 that a "patriotking" would unify his people: "instead of puttinghimself at the head of one partyin orderto govern his people,

he will put himself at the head of his people in orderto govern, or more properly to subdue, all parties."41James Madison, arguingin 1787 that one of the

virtues of a properconstitutionwas its capacity "to breakand control the violence of faction,"commented"thatthe public good is disregardedby the conflicts of rival parties."42Indeed, a good deal of Madison's collaborationwith

HamiltonandJay on TheFederalistwas devotedto demonstratingthatthe new

constitutionwould avert such dangers.

The core issue is not the existence, nor even the tactics, of concertedefforts

to attractvoters to office-seekers who were in coalitions based on kinship,

friendship,mutualself-interest,or policy; the more difficulthistoricalproblem

is the shift in legitimacy of such activities. The air of disreputethathung over

election-contesting organizationswould have been particularlysalient when

The Federalist addressedthese concerns, for the revolutionaryperiod in the

United States saw the proliferationand developmentof caucuses, conventions,

and coalitions (and their condemnationas cabals) on a wide scale, as election

campaignsproliferated.And the new countrysaw the formationof a majoroppositionalgroupingin the form of the Republicans.43Yet an element of opprobriumwas attachedto all this activity.44

It is hardto be sure where and when the idea of a partybegan to change, and

39 Some of this moralcondemnation

may representthe lingeringinfluence of the medieval tradition of elections within the Church,when open office-seeking was taboo, because it was associated with the serious sin of simony, or traffickingin ecclesiastical office (L6o Moulin, La Viequotidienne des religieux et religieuses au Moyen Age, xe-xve siecle [Paris:Hachette, 1978], p. 196).

In Canto 19 of Inferno,Dante wedged simoniacsupsidedown in holes with theirfeet on fire. Twentieth-centurycanonlaw continuesto barelectioneering(J. Creusen,Religieuxet religieusesd 'apres

le droit eccldsiastique [Paris: L'Edition Universelle, 1950], p. 53).

40 For much insight into unitary conceptions see Jane M. Mansbridge, Beyond Adversary

Democracy(New York:Basic Books, 1980).

41 Henry Saint-John,Viscount Bolingbroke, The Works of Lord Bolingbroke

(London: Cass,

1967), v. 2, p. 402.

42

James Madison, "FederalistNo. 10," in The Federalist, Jacob E. Cooke, ed. (Middletown,

CT:WesleyanUniversityPress, 1961), pp. 56-57.

43 There is an enormousliteratureon

the early history of partiesin the United States. Two importantstatementsare:Hofstadter,TheIdea of a PartySystem;and StanleyElkins andEric McKitrick, TheAge of Federalism (New York:OxfordUniversityPress, 1993), pp. 257-302.

44

Robert J. Dinkin, Voting in Revolutionary America: A Study of Elections in the Original Thir-

teen States, 1776-1789 (Westport,Conn: GreenwoodPress, 1982), pp. 57-89.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

670

JOHN MARKOFF

it undoubtedlycannot be identified with a single moment or a single place.

Some scholarshipsuggests the early nineteenth-centuryUnited States as one

importantlocation.The old critiqueof "faction"was retainedfor the personalistic coalitions that were clusteredaroundfamily or held togetherby greed; a

"party"was increasinglylikely to be an impersonalbody united aroundcommon principle.45By the 1820s, adherentsof New YorkState's DemocraticRepublicanswere openly proclaimingtheir loyalty to the party,and were championing the very idea of partyas an antidoteto the new forms of tyrannythat a

republiccould nurture:"Whenpartydistinctionsare no longerknown and recognized, our freedomwill be in jeopardy,as 'the calm of despotism'will then

be visible." No longer was the partylabel to be denied:"Wearepartymen, attached to partysystems."46

By the middle of the nineteenthcentury,those who called themselves democratsin Europehad generallyacceptedthe notion of partyas a properform

of organization,ratherthan as the corruptionof some ideal. Although the left

in France'sRevolutionof 1848, for example, looked back in many ways to the

Revolution of 1789 for models, it also accepted the partylabel.47The history

of ideas of partyin France-and elsewherein Europe-between 1789 and 1848

remainsto be written.48

Conflation of Democracy with Representative Institutions

This was an Americaninnovation.Thomas Paine recognized the significance

of such conflationalmost instantly,characterizingthe new U.S. political model as "representationingraftedupon democracy."49In the 1780s, many writers

thoughtof representativeinstitutionsas somethingquite distinct from democracy. James Madison distinguished"republics"like the thirteennewly independent states from "puredemocracy"precisely because they had a "scheme

45 Wallace, "ChangingConcepts of Party."

46 Quoted in

Wallace, "ChangingConcepts of Party,"p. 487. Similar notions were expressed

earlierin Sweden (Roberts,Swedishand English Parliamentarisin,p. 26).

47

See, for example, RonaldAminzade,Ballots and Barricades:Class Formationand Republican Politics in France, 1830-1871 (Princeton:PrincetonUniversityPress, 1993). The term "parties" continuedto retainenough of its pejorativesense thatLouis Napoleon Bonaparteclaimed to

identify with the whole nationby being above party.Rathermore recently,after a close victory in

Poland's bitterpresidentialelection in 1995, the victor resigned from the DemocraticPartyof the

Left in orderto be a presidentoutside the partysystem (New YorkTimes,November26, 1995, I, p.

6). Indeed,condemnationof partiesand partysystems has been a strikingpartof the political culture of post-communistdemocratization,as witness anti-partystances by such diverse figures as

Poland's Lech Walesa, the Czech Republic'sVaclav Havel, and Russia's Boris Yeltsin. For suggestive observationssee Linz and Stepan,Problemsof Democratic Transitionand Consolidation:

SouthernEurope, South America, and Post-CommunistEurope (Baltimore:The Johns Hopkins

UniversityPress, 1996), p. 247.

48 In Jean Dubois's dictionarywe find that around 1870 there was a wide range in use of the

term"party,"from the pejorativethroughthe neutralto the honorific.See Le Vocabulairepolitique

et social en France de 1869 a 1872 (Paris:Larousse, 1962), pp. 366-67.

49 ThomasPaine, Rightsof Man, in PhilipS. Foner,ed., TheCompleteWritingsof ThomasPaine

(New York:CitadelPress, 1969), v. 1, p. 371.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE

AND

WHEN

WAS DEMOCRACY

INVENTED?

671

of representation."50

Common Europeannotions of representationenvisaged

some mechanism,not necessarily electoral, by which delegates presentedthe

views of the ruled to the ruler.Democracy,in contrast,was often perceived as

the directinvolvement of citizens in decision-making5, which even an enthusiast like Rousseauthoughtinappropriateto a largeterritorialstate.Rousseau's

scorn for elected representationwas notable:"The people of Englandregards

itself as free, but it is gravely mistaken. It is free only duringthe election of

membersof Parliament.As soon as they are elected, slavery overtakesit, and

it is nothing.The use it makes of the shortmoments of libertyit enjoys merits

losing them."52Few thoughtBritain'sparliamenthad much to do with democracy afterthe upheavalsof the mid-seventeenthcenturygave way to a restored

monarchy.Indeed,as late as the debateson the ReformBill of 1832, the champions of limited suffrageexpansioncould deny the slanderousaccusationthat

they were democrats.53

Those who held themselves to be democratsduringthe FrenchRevolution

sometimes avowed a suspicion that representativeswere but a step from becoming new aristocrats.54Indeed, favorable and unfavorableinvocations of

"democracy"tendedto occur in the context of criticizingelected revolutionary

officials for their autonomy from popularcontrol. Sieyes, for example, condemned the "ignorance"of those who held "therepresentativesystem incompatiblewith democracy."55But in 1795 Holland'smobilizeddemocratsin Rotterdaminsisted that "Representatives"are no more than "the executors of our

Will since we have alienatedno partof our sovereignty."56Although negative

views of democracywere a commonplaceby the time the Americanconstitu50

James Madison, in Federalist No. 10 (in Cooke, ed., The Federalist, p. 62). See also Robert

W. Shoemaker."'Democracy'and 'Republic'as Understoodin Late EighteenthCenturyAmerica",

AmericanSpeech41. 1966, pp. 83-95.

5

Acknowledging the common view that democracywas a formulafor continuedviolent revolt, D'Argenson in 1765 made the uncommonsuggestion of a democraticroad to orderthrough

popularly elected authorities,anticipatingthe later conflation of democracy and representation

(Rosanvallon,"Historyof the Word'Democracy',"p. 143).

52

Jean-JacquesRousseau,Du Cottrat social, Book III,ch. 15 (Paris:AubierMontaigne,1943),

p. 340. Montesquieudiffered with Rousseauon much, but also saw elected representativesas incompatiblewith "democracy":"Thesuffrageby lot is naturalto democracy;as thatby choice is to

aristocracy"(The Spiritof the Laws [New York:Hafner, 1949], v.1, p. I1).

53 The radicalHenryHunt'saccountof the ministerialreformers'responseto attacks the conby

servativeSir RobertPeel: "WhenSir RobertPeel chargedthem [the ministers]with going to make

a democraticalHouse of Commons ... they said 'No, we are going to keep power out of the hands

of the rabble'"(quoted in Michael Brock, The Great ReformAct [London:HutchisonUniversity

Library,1973], p. 187.

54 On the developmentof moreparticipatorynotions of democracyandtheirconflicts with

representation,see R.B. Rose, The Makingof the Sans-Culottes:DemocraticIdeas and Institutionsin

Paris, 1789-92 (Manchester:ManchesterUniversityPress, 1983); KareT0nneson,"LaDemocratie Directe sous la R6volutionFrancaise",in Colin Lucas, ed., The FrenchRevolutionand the Creation of ModernPolitical Culture,vol. 2: The Political Cultureof the FrenchRevolution(Oxford:

PergamonPress, 1988), pp. 295-307.

55 Quoted in Rosanvallon,"The

History of the Word 'Democracy',"p. 148

56

Quoted in Simon Schama,Patriots and Liberators,p. 226.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

672

JOHN MARKOFF

tion was ratified,manyAmericansfelt thatthey had createda new kind of government,and some were using the word "democracy"to describeit.57

Accountability of all Powerholders to an Electorate

This very powerful idea was profoundlyadvancedin the new United States,

whose constitutionof 1789 rejected a hereditarymonarchy,a hereditaryaristocracy,and an establishedchurch.No one was to be presidentor sit in Congress by right; other powerholderswould either be elected, or appointedby

those who wereelected. In France,electoralprocesseswereenlargedby the new

revolutionaryregime. Officials from village councilmento nationallegislators

(but not the king) were to be elected, as were magistrates,public prosecutors,

National Guardofficers, Catholicbishops, and even army sergeants(a plan to

add schoolteacherswas never implemented).58Althoughthe scope of electoral

institutionskept changing,by 1792 the unelectedking was gone. The radicalism of makingall powerholdersresponsibleto those down below was, however, attenuatedby the propensityto indirectelections in boththe U.S. andFrench

cases.59The history of democracyin most of nineteenth-centurywestern Europe was markedby the coexistence of elected parliamentsandhereditarymonarchs, who battled over their respective powers. The unhappyhistory of the

French constitutionof 1791, for example, ended with its abrogationand the

king's trialby parliamentand execution.

There is a long traditionof partialprecursorsin Europeanhistory, such as

city-states governed by councils60 and elected monarchssuch as the Polish

king, the emperor,or the pope; andmuchexperiencewith electoralprinciples61

in variousforms of corporategovernance(includingmonasticorders,villages,

guilds and other forms of association as well).62At the nationallevel, howev57 Wood, Creationof the AmericanRepublic,pp. 593-96.

58 Isser Woloch, The New Regime: Transformationsof the French Civic Order, 1789-1820s

(New York:Norton, 1994), pp. 60-64.

59 The initial U.S. design had senatorselected by state legislaturesand presidentsby an electoralcollege; the Frenchtendedto have a varietyof multistageelections from the Estates-General

throughthe Directory.

60 Daniel Waley, The Italian City.-Republics(New York: McGraw Hill, 1969), pp. 60-65;

Moulin, "Les origines religieuses des techniqueselectoraleset d6liberativesmodernes,"RevueInternationaled'Histoire Politique et Constitutionelle(nouvelle s6rie) 3-4, 1953-54, pp. 106-48.

61 Towncouncils often hadecclesiastics who sat ex officio; manybodies practicingelectio were

engaged in acts of collective acclamation,ratherthan in choosing among alternatives.See Pierre

Rosanvallon, Le sacre du citoyen: Histoire du suffrage universel en France (Paris:Gallimard,

1992), pp. 30-34. On the otherhand,notions of division and majorityrule arealso not hardto find

in the Europeanpast, as in the Genoese statutesof 1143 or the apparenttwelfth-centuryIcelandic

decision-makingby majority(Moulin, "Techniqueselectorales,"p.112; SigurdurLindal, "Early

DemocraticTraditionsin the Nordic Countries,"in ErikAllardtet al., Nordic Democracy [Copenhagen:Det Danske Selskab, 1981], p. 18).

62 Moulin, Religieux et religieuses, pp. 191-208 and "Les origines religieuses des techniques

6lectorales."Babeau,Le village sous l'AncienRegime,pp. 62-64. Emile Coornaert,Les Corporations en France avant 1789 (Paris:Gallimard,1941), p. 214. Electoralprocedurescould be well

enoughestablishedthatchargesof election irregularitiesmightfigure in internalguild disputes;for

an interestingexample, see Daniel Heimmermann,"'The Blackest of Treasons': Strife Among

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE AND WHEN WAS DEMOCRACY INVENTED?

673

er, such mechanisms were invariablyjoined with notions of hereditaryright.

Even the Polish nobility who elected the king were an almost closed (although

very large) hereditarygrouping. Thus Europeansocial contracttheory often

stressedthe notion of a contractbetween the monarchand the representatives

of the people, andsaw as a fundamentalpoliticalquestionthe extractionof power-limiting concessions from that monarch.The question of checks and balances for Montesquieu,for example, was how to offset monarchicalpower by

otherpower.In the exhilaratingdiscussion aboutnew institutionsto be created

thataccompaniedthe Americancolonies' defeat of the Britisharmy,the participants realized that their social contractwould be quite otherwise: a contract

among the people that created centralized power.63 How to avoid the recreationof eithermonarchicalor aristocratictyrannies,ratherthanhavingmonarchs and aristocratseach as counterweightsto the other,became a centralissue for applied political theorists on the western side of the Atlantic, which

made the Americanexperienceseem quite irrelevantto many democratsacross

the ocean.

As nineteenth-centuryEuropeansattemptedto reconcile monarchicaland

aristocraticinstitutionswith the newly powerful idea of democraticlegitimation opened up by revolutionaryFrance,they began a long history of struggle

between legislaturesthathad some degreeof democraticlegitimationand some

recognized power, and those whose power derived from birth, tradition,and

God. The republicanismof Franceand its satelliteswas crushedexternally,but

only afterit hadbeen pushedasideby Napoleon'snew monarchicalorder.Many

nineteenth-centuryEuropeancountrieshad some sort of parliament,but monarchsoften retainedthe power to name and dismiss ministers,drawup budgets,

and ordertheir armies into combat;in many places, elected chambersshared

power with "upper"chamberscomposed of hereditaryor monarchicallyappointed members.

In oppositionto claims of tradition,Jeffersonheld thatgovernmentwas exclusively at the service of living humanbeings, since "thedead have no rights.

They are nothing;and nothingcannotown something... This corporealglobe,

and everythingupon it, belong to its presentcorporealinhabitantsduringtheir

generation."64

MastersInside the LeatherGuilds of Eighteenth-CenturyBordeaux",paperpresentedto the meetings of the Society for FrenchHistoricalStudies,Lexington,Kentucky,1997. Thatleadershipcould

derive from the consent of the led, ratherthanbe bestowed by higherauthority,would have been a

likely experienceof the crews of piratevessels in the early modernAtlanticworld. Piratecrews not

only elected theircaptains,but were familiarwith countervailingpower (in the forms of the quartermasterand ship's council) and contractualrelationsof individualand collectivity (in the form of

writtenship's articles specifying sharesof booty and rates of compensationfor on-the-jobinjury).

See MarcusRediker,Betweenthe Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: MerchantSeamen,Pirates and the

Anglo-AmericanMaritimeWorld,1700-1750 (New York:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1987), pp.

261-66.

63 For a

very rich treatment,see GordonWood, The Creationof the AmericanRepublic.

64

Thomas Jefferson,"Letterto Samuel Kercheval"(12 July 1816) in The Writingsof Thomas

Jefferson (Washington,D.C.: Thomas JeffersonMemorialAssociation, 1903), v. 15, pp. 42-43.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

674

JOHN

MARKOFF

The first groupof countriesto follow the UnitedStatesandFrancein the radical breakfromhereditaryauthoritywere the newly independentstatesof Spanish America.Although these new states are often denigratedfor "merely"aping the NorthAmericanexample, it surely matteredon the world stage thatthe

republicaninitiative-as of, say, 1840-was representedin a whole group of

countries,not a largelyisolated United States.65The Europeof the Congressof

Viennawas not following thatexample at all.

Secret Ballot

Variousvoting mechanismshadlong been known66,but secrecywas not always

favoredby eighteenth-centuryadvocatesof popularsovereignty.67In the view

of some, the vote was only appropriatefor those of independentconscience; a

truecitizen proudlyvoted in public.As the GirondinLouvetput it: "Decreethat

we shall not write;decree that each shall speak up firmly 'I am so-and-so and

I name so-and-so.' That's the ballot worthy of free men."68Others held that

written ballots lent themselves to fraudulentvote counts.69But still others

claimed thatpublic voting made elections into acts of hierarchiesor collectivities, ratherthan a summationof individualwills. For some, this was a recommendation:in some versions of this view those down below would defer to the

voting choices of theirbetters;in otherversions,communitieswould makecollective choices.70Montesquieuheld open voting essential to maintainthe rule

65 The

easy demonstrationthat Latin America'sdemocraticinstitutionswere characterizedby

clientilism, corruption,fraudand violence is hardlyever put in a comparativecontext in which actual electoralpracticesin nineteenthcenturyNorthAmericaor Europe-not supposedideals-are

taken as the benchmark.Such comparativestudies are long overdue. It may be the case that during, the 1820s and 1830s, for example, clientilistic voting was more characteristicof Brazil than

Bavaria, violence more likely to accompany attemptsto exercise rights that existed on paper in

Chile thanKentucky,and fraudulentvote counts more characteristicof VenezuelathanVenice but

it is far from obvious. Consider,for example, Alain Garrigou'sdiscussion of nineteenth-century

Frenchvoting in Le Voteet la vertu: Commentles francais sont devenus dlecteurs(Paris:Presses

de la FondationNationaledes Sciences Politiques, 1992).

66 Secret ballots were used in some medievalecclesiastical elections, which suggests the possibility of the preservationof electoraltechniquesfrom antiquity(Moulin,"Techniqueselectorales,"

p. 144).

67 Alexis de Tocquevillecontendedin 1835 that secret ballots were unimportantfor American

democratssince "therehas been too little dangerin a manmakinghis vote publicto createany great

desire to conceal it" (cited in Bourkeand DeBats, "IdentifiableVoting,"p. 261).

68 Quoted in Gueniffey,Le nombreet la raison, p. 310.

69 For some examples from colonial NorthAmerica, see RobertJ. Dinkin, Votingin Provincial

America:A Studyof Elections in the ThirteenColonies, 1689-1776 (Westport,Conn.:Greenwood

Press, 1977), p. 135.

70 The following works treatthese issues in the English context:Paul F. Bourke and DonaldA.

America:TowardA Comparisonof Britainand

DeBats, "IdentifiableVotingin Nineteenth-Century

the United States before the Secret Ballot,"Perspectivesin AmericanHistory 11, 1977-1978, pp.

259-88; David C. Moore, The Politics of Deference:A Studyof the Mid-NineteenthCenturyEnglish Political System(Hassocks:HarvesterPress, 1976);T.J.Nossiter,Influence,Opinionand Political Idioms in ReformedEngland: Case Studiesfrom the North-east, 1832-1874 (New York:

Harperand Row, 1974). For French revolutionarydebates and shifting practices, see Gueniffey,

pp. 281-316.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE

AND

WHEN

WAS DEMOCRACY

INVENTED?

675

of enlightenedelites over dangerousplebeians:"by renderingthe suffragesecret in the Roman republic, all was lost; it was no longer possible to direct a

populace that sought its own destruction."71Whetherthose who thought of

themselves as democratsfavored open or secret voting was in parta question

of the changing general notions of "democracy,"and in parta question of immediatecircumstances.In Oregon,for example,the politicalelite seems to have

maintainedopen voting duringthe AmericanCivil War,in orderto stifle potentialdisloyalty to the Union.72Illinois, to take anotherinstance,adoptedoral

voting in 1818, ended it in 1819, reinstitutedit in 1821, ended it again in 1823,

opted for it yet again in 1829, and terminatedit in 1848.73

One of the reasonswhy a writtenballot mightbe associatedwith aristocracy,

ratherthandemocracy,was the absence of organizedpartiesand the generalillegitimacy of open election-contestingactions. Frenchrevolutionaries,for example, had no legitimateelection-contestingorganizationsand no election bureaucracyto draw up lists of candidates:voters could not pick colored ballots,

or check off symbols or names on preparedsheets of paper,but were expected

to offer a namealoudor in writing.Undersuchcircumstancesa mandatorywritten ballot, secretor otherwise,would exclude the illiterateand would largelybe

desiredor condemnedfor thatreason.Frenchdemocratsoften arguedthatpreservingopen voice voting was an essentialweapon againstaristocracy.74

In France,moreover,the revolutionaries'electoral traditionbegan with the

convening of assemblies to draw up lists of grievances, as well as to elect

deputiesto higherbodies in a multistepprocess. This imparteda collective flavor to voting thatwas retainedthroughthe entirerevolutionaryperiod.The constitutionof 1793, for example-the earliest moment in the history of modern

democracyof legislated universalmanhoodsuffrage-calls for voting to take

place in primaryassemblies that elect delegates to higher bodies; at those primary assemblies, citizens were to choose between oral and writtenvoting.75

The historicalrangeof electoralprocedurescould vary enormouslyin openness/closedness: in nineteenth-centuryEngland,votes were writtendown and

later published; in nineteenth-centuryAmerica, voting was often public and

oral; in the twentieth-centurySoviet Union, a voter had the option of a secret

ballot, but to choose to enter the voting booth was tantamountto a confession

of dissidence76;in many times and places, written ballots were identifiable

7'

Montesquieu,The Spiritof the Lawvs,v. 1, p. 12.

72 Bourke and DeBats, "Identifiable

Voting,"p. 273

73 Bourkeand DeBats, "IdentifiableVoting,"p. 270

74 Malcolm Crook, Elections in the French Revolution;

Gueniffey, Le nonbre et la raison.

75

33.

Duverger, Constitutions, p.

Alex Pravda,"Electionsin the CommunistPartyStates,"in Guy Hermet,RichardRose, and

Alain Rouquie, Elections WithoutChoice (New York:Wiley, 1978), p. 177. The dominantWhigs

of Massachusettsin 1853 crucially modified a two year old law requiringballots to be placed in

envelopes, by makingthe requestfor such an envelope a voter's option (Wigmore,AustralianBallot, p. 26).

76

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

676

JOHN

MARKOFF

(easily distinguishable,for example, if differentlycolored paper represented

differentcandidatesor if political partiesdistributedtheir own ballots).77The

task of tracingthe history of voting forms is complicatedby the possibility of

non-uniformprocedures,not to mention the frequentgap between legislative

enactmentsand discrepantpractices.Although France'sconstitutionof 1848,

for example, requireda secret ballot, the effective achievementof secrecy in

thatcountryshouldbe datedfrom 1913, when voting booths were mandated.78

No country effectively and uniformly required the secret ballot before

Britain'sAustraliancolonies, and more specifically Victoria and South Australia( 1856).79Recently-establishedVictoriahadlittle in the way of established

electoral tradition,and much in the way of social turbulence.The secret ballot

idea may have been carriedto Australiaby immigrantswith experienceof it in

some of Britain'sdistricts.80A more importantsource was probablytransported Britishworkersin the towns and gold fields, who had carriedwith them the

program of the Chartist movement (including secret balloting). Australia's

identity as the model for this practicewas firm enough that in debates on voting mechanismsin England,the United States, and LatinAmerica,the use of a

publicly-providedballot thatwas markedin secretbecame known as the "Australianballot."81 In the 1870s and 1880s, several Europeancountriesfollowed

suit.82A wave of U.S. locations followed startingwith Louisville, Kentuckyin

1888.83Indiana,Montana,andMassachusettsrequiredit statewidein 1888 and

1889; it spreadconsiderablyin the next decade.84

In spite of the Australianlabel, however, a numberof otherplaces had laws

77 At one point in colonial RhodeIsland,for example, writtenballotswere signed on the reverse

side (Dinkin, Voting in Provincial America, p. 137).

78 "Constitution du 4 novembre 1848" in Duverger, Constitutions et documents

politiques,

p. 92; Olivier Duhamel,Aux Urnes, Citoyens(Paris:Editionsdu Mai, 1993).

79 See J.F.H. Wright, Mirror of the Nation's Mind: Australia's Electoral Experiments (Sydney:

Hale and Ironmonger,1980), p. 24 et seq.; Lionel E. Fredman,TheAustralianBallot: TheStory of

an AmericanReform(East Lansing:Michigan State University Press, 1968), pp. 3-11; the background is discussed in I.D. McNaughton,"ColonialLiberalism, 1851-1892," in G. Greenwood,

ed., Australia: A Social and Political History (London: Angus and Robertson, 1955), pp. 98-144.

A leading opponentof the innovationheld it "notonly unconstitutional,but un-English"and added

"no Englishmanwould desire to do that secretly which ought to be done fairly and openly" (quoted in Wright,Mirror,p. 27).

80 For a possible instance, see John H. Wigmore, The Australian Ballot System (Boston: Soule,

1889), p. 2.

81 Althoughmost of the countryadoptedthe secretballot for legislative elections between 1856

and 1859, its use in local elections was a slightly laterdevelopment.WesternAustraliawaited until 1879, which seems to makeNew Zealandthe firstplace actuallyto institutionalizesecrecy at the

national level (1870). Spencer D. Albright, The American Ballot (Washington,DC: American

Council on Public Affairs, 1942); The Modern Encyclopedia of Australia and New Zealand (Syd-

ney: Horwitz-Graham,1964), p. 129.

82 Britain acted in 1872, Belgium in 1877, Luxembourgin 1879 (Albright,AmericanBallot,

p. 24).

83 Kentuckymaintainedoral voting in ruralareasuntil 1891 (Bourkeand DeBats, "Identifiable

Voting",p. 270 n. 2).

84

Albright, American Ballot, pp. 26-27.

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE

AND

WHEN

WAS DEMOCRACY

INVENTED?

677

on the books at an earlierdate. In Colombia, secret ballots have been the formal rule since the constitutionof 1853, althoughscholarsquestion the extent

of enforcementof these provisions, particularlysince political partiesdistributed their own ballots until 1988.85

Extension of Suffrage: The Propertyless86

This is a difficult matterto assess, because many countrieshave both national

andlocal elections to consider;in some countries,like the UnitedStatesorAustralia,state or provincialelections must be consideredas well. It is also sometimes difficult to distinguishbetween the voting rules in law and actualpractice, particularlyin ruralregionsfarfromthe scrutinyof the centralgovernment

andurbanjournalists.Finally,systems of multistageelections may have greater

restrictionsat higher stages.

The French constitutionof 1793 seems to be the first attemptto eliminate

propertyor wealth qualificationsat the nationallevel. It supersededthe constitution of 1791, which had establisheda minimal tax paymentfor participants

in primaryelectoral assemblies (but a higher payment for second-stage electors).87The constitutionof 1793, however, never went into effect (althoughit

was ratifiedby a referendumwith broadsuffrage).By the early nineteenthcentury many of the states of the new United States had eliminatedsuch requirements for white men. By 1825 all but three states had universal suffrage for

white men.88Switzerland'sProtestantcantonsliberalizedmale suffragein the

1830s by reducing-but not necessarilyeliminating-tax thresholds(although

sometimestherewere otherrestrictions).89In Geneva,the requiredtax payment

85

See "Colombia"in DieterNohlen, ed., EnciclopediaElectoralLatinoamericanay del Caribe

(San Jose, Costa Rica: InstitutoInteramericanode Derechos Humanos, 1993), p. 139; Jonathan

HartlynandArturoValenzuela,"Democracyin LatinAmerica Since 1930,"in Leslie Bethell, ed.,

The CambridgeHistory of LatinAmerica (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press, 1994), v. 6,

part2, pp. 129- 30. David Bushnell finds thatthe elections of the 1850s were sometimescontrolled

by local bosses, but largely accordedwith the official rules ("VoterParticipationin the Colombian

Election of 1856," HispanicAmericanHistorical Review51, 1971, pp. 238-49).

86 The

precise mechanismfor such exclusions was often the setting of a minimumtax rate. I

omit here a separatetreatmentof literacy exclusions, althoughthey have been very importantin

some countries.UnderEcuador's 1929 constitution,for example, "citizens"had to readand write,

thereby excluding sixty four percentof adults from voting rights. See Rafael QuinteroL6pez, El

mito del populismo en el Ecuador:Andlisis de los fundamentosdel Estado ecuatoriano moderno

(1895-1934) (Quito:UniversidadCentraldel Ecuador,1983), p. 226.

87

Duverger,Constitutions,pp. 8-9, 32-33. The tension inherentin combininggrassrootsparticipationin collective assemblies with the delegationof effective decision-makingto a higherlevel is characteristicof the difficult relationship between direct democracy and representation

throughoutthe entirerevolutionaryperiod in France.See Gueniffey,Le nombreet la raison.

88 GordonWood, The Radicalismof the AmericanRevolution,pp. 294-95. The pioneers,Vermont and New Hampshire,eliminatedpecuniaryrequirementsbefore 1800 (LauraJ. Scalia, America's JeffersonianExperiment:RemakingState Constitutions,1820-1850 [DeKalb, IL: Northern

Illinois UniversityPress, 1999]).

89 ValentinGitermann,Geschichte der Schweiz (Thayngen:Augustin-Verlag,1941), pp. 44748. For a contemporarysurvey of cantonalvariationin democraticpracticeas of 1843 (the author

distinguishessix types of cantonalgovernment),see A.-E. Cherbuliez,De la ddmocratieen Suisse

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

678

JOHN

MARKOFF

was reducedin 1819, againin 1832 and 1834, and eliminatedin 1842. At those

moments,one can see the erosion of the tax thresholdfrom the most restrictive

sixty-threeflorins set in the post-Bonaparteconstitutionof 1814, to twentyfive, fifteen, seven, and finally zero, although the 1842 constitution still excluded those recently on public assistance. In 1847 yet anotherconstitution

droppedthis final restriction.90Following the defeatof its conservativecantons

in a civil warin 18479 -a triggerof the revolutionarywave of 1848-Switzerland's new constitutionbecame the first in Europeto eliminate such requirements at the nationallevel.92France'srevolutionaryconstitutionof 1848 eliminatedpropertyqualificationsfor men a few weeks afterthe Swiss constitution

was adopted,but a more restrictiveset of rules was soon reintroduced,before

France'sSecond Republicwas shut down by its elected president.93

There are also some precocious cases in Latin America. An 1812 election

held in Mexico City seems to have had very wide suffragein practice,because

officials did not enforce the legal restrictions.94In principle,the Cadiz Constitutionof 1812-under which colonial elections wereheld-provided wide suffrage for non-Blackmen.95In defiance of the standardimage of LatinAmericans looking to Europefor models of democraticprogress,we find a Mexican

liberallooking to Europefor models of how to restrictpopularparticipationin

electoral politics.96For conservativeforces in independentSpanishAmerica,

the Europeshapedby the Congressof Viennawas a sourceof guidanceon how

to put a cat back into a bag.

An 1821 post-independencelaw in BuenosAires provinceprovidedfor "universal"suffragefor free men97;but servants,day laborers,and illiterateswere

(Paris:Cherbuliez,1843), v. 2. Cantonalconstitutionsfrom the 1830s and 1840s arefound in Ludwig Snell, Handbuchdes SchweizerischenStaatsrechts(Zurich:Drell, 1844), v. 2.

90 William E. Rappard,L'Avesementde la democratie modernea Geneve (Geneva: Jullien,

1942), pp. 83, 143, 191-92, 214, 316, 410-11. By contrast,Zuricheliminatedthe tax threshhold

in 1831 (Rappard,L'Individuet l'dtat dans l'dvolutionconstitutionellede la Suisse [Zurich:Editions Polygraphiques,1936], p. 195).

91 JoachimRemak,A VeryCivil War:The Swiss SonderbundWarof 1847 (Boulder,CO: Westview Press, 1993).

92 Article 63 of the 1848 constitutionenfranchisedthose "notexcluded from the right of active

citizenshipby the legislationof the cantonin which he has his domicile."This would seem to leave

open the possibilityof cantonalrestrictions.(See "Constitutionfederalede la confederationsuisse

de la Suisse [Boudry:Edidu 12 septembre1848,"in WilliamE. Rappard,La Constitutionfededdrale

tions de la Baconiere, 1948], p. 431). In light of post-1848 exclusionaryprovisions in some cantons, scholars differ in their assessments of Swiss democracyat mid-century.See, for example,

DietrichRueschemeyer,Evelyne HuberStephens,and John D. Stephens, CapitalistDevelopment

and Democracy(Cambridge:Polity Press, 1992), p. 85; GoranTherborn,"TheRule of Capitaland

the Rise of Democracy,"New Left Reviewno. 103, 1977, p. 16.

93 RaymondHuard,Le Suffrageuniversel en France (1848-1946) (Paris:Aubier, 1991); Duverger,Constitutions,p.92.

94 RichardWarren,"The Will of the Nation: Political Participationin Mexico, 1808-1836,"

paperpresentedat the meetings of the LatinAmericanStudiesAssociation, Los Angeles, 1992.

95 Excluded were those of Africandescent, the unemployed,and domestic servants.

96 TorcuatoS. Di Tella, National Popular Politics in Early IndependentMexico, 1820-1847

(Albuquerque:Universityof New Mexico Press, 1996), pp. 97-98.

97 This seems to be

following a precedentset in an election of 1812, accordingto TulioHalperfn-

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHERE

AND WHEN

WAS DEMOCRACY

INVENTED?

679

excluded five years later.98In the militarizedclimate thatemergedfrom the independence wars, a substantialnumberof voters were government soldiers,

leading the opposition to complain of the grantof "the suffrageand the lance

to the proletarian."One might wonderaboutthe climate of intimidationfueled

by such armedvoters, but the government'scandidatesdid sometimes lose at

the polls. In shortorder,however,the electoral system was utilized for plebiscitarianlegitimationby JuanManuel de Rosas.99

Therewas no "Argentine"governmentto speakof at this point, althoughdevelopments in Buenos Aires and other provinceshad considerablemutualimpact. The frontierprovince of Entre Rios had provided voting rights for free

adultmales even earlier(1820), althoughit adoptedsome restrictionstwo years

later.The provinceof Corrientesadoptedsimilarrightsin 1821. NorthernSalta

provincealso enfranchisedfree adultmales in 1823, andUruguayfollowed suit

in 1825 (in indirectelections), but abandonedbroadsuffragetwo years later.0?

Brazil's constitutionof 1824 providedfor such broadparticipationat the base

of a multistageprocess, despite its explicit and implicit exclusions, that even

underthe more restrictiverevised law of 1846 conservativeBrazilianscould

lament "universalsuffrage."'0'

Extension of Suffrage: Women

At the outsetof the moderneraof democratization,women were not completely

deprivedof the vote. The absence of codified suffragerules may have permitted small numbersof women to seek the vote, and election officials to permit

them;corporatenotions of representationentitledfemale fiefholdersand members of convents to be representedin France'sEstates-Generalof 1789 through

male surrogates,while the widows of urbanguild mastersand female heads of

ruralhouseholds could attendtown and village assemblies in person. In early

post-independenceAmerica a small numberof women could also vote. Even

where laws permittedwomen's voting, if only by silence, informaldefinitions

of women's roles seem to have effectively kept participationlow.'02 The sysDonghi, Politics, Economics and Society in Argentina in the Revolutionary Period (Cambridge:

CambridgeUniversityPress, 1975), p. 361.

98 See David Bushnell, Reformand Reactionin the Platine Provinces,1810-1852 (Gainesville,

FL: Universityof FloridaPress, 1983), pp. 22-23.

99 Halperin-Donghi,Politics, Economics,and Society,pp. 360-64.

100

Bushnell, Reformand Reaction,pp. 34, 36-37, 43, 134-36.

10 RichardGraham'sexemplarystudyshows thatin 1870, when the 1846 law was still in force,

more thanhalf of free adult men had the right to vote. Since the languageof the 1824 constitution

suggests an electorateat least as large, it seems probablethat in the 1820s Brazil had a more generous suffragefor free males thanalmost anywherein Europe.See RichardGraham,Patronageand

Politics in NineteenthCentury,Brazil (Stanford:StanfordUniversityPress, 1990), pp. 101-09.

102 In the elections for the Estates-General,for example, those women entitled to participate

(such as widows of membersof urbanguilds) only very rarelyactuallydid so. See Michel Naudin,

"Les elections aux 6tats-generauxpour la ville de Nimes," Annales historiquesde la Revolution

francaise 56, 1984, pp. 497-98; the official rules for the Estates-Generalcan be found in Jacques

Cadart,Le Regimeelectoral des etats gednrauxde 1789 et ses origines (1302-1614) (Paris:Sirey,

1952).

This content downloaded from 79.175.88.212 on Thu, 1 Aug 2013 01:09:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

680

JOHN

MARKOFF

andthe craftingof new statecontematizingworkof Frenchrevolutionaries103

stitutionsin the U.S. meantthatthe modem democraticera virtuallybegan by

completing and systematizingthe disfranchisementof women.104

New Zealand was the first country to secure women's voting rights in national elections (in 1893).105 Australiafollowed suit in 1902 (althoughwomen

could not vote in all elections in all states until 1908). Perhapsthe shortageof

women in these two frontiersocieties and the desire to attractwomen immigrants from Europe played a role in this decision, especially for those who

sought to infuse these male-dominatedlands with the civilized values that