Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Neurotheology PDF

Загружено:

jorgemauriciocuartasИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Neurotheology PDF

Загружено:

jorgemauriciocuartasАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Iranian Journal

of Neurology

Special Article

Iran J Neurol 2014; 13(1): 52-55

Neurotheology: The relationship

between brain and religion

Received: 19 Aug 2013

Accepted: 20 Nov 2013

Alireza Sayadmansour1

1

Department of Philosophy, School of Literature and Humanities, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

Keywords

Brain, Causality, Functional Brain Imaging, Neurotheology,

Prayer, Spirituality

Abstract

Neurotheology refers to the multidisciplinary field of

scholarship that seeks to understand the relationship

between the human brain and religion. In its initial

development, neurotheology has been conceived in very

broad terms relating to the intersection between religion

and brain sciences in general. The author's main objective

is to introduce neurotheology in general and provides a

basis for more detailed scholarship from experts in

theology, as well as in neuroscience and medicine.

Introduction

Neurotheology,

also

known

as

"spiritual

neuroscience"1, is an emerging field of study that

seeks to understand the relationship between the

brain science and religion.2 Scholars in this field, strive

up front to explain the neurological ground for

spiritual experiences such as "the perception that time,

fear or self-consciousness have dissolved; spiritual

awe; oneness with the universe."3 There has been a

recent considerable interest in neurotheology

worldwide. Neurotheology is multidisciplinary in

nature and includes the fields of theology, religious

studies, religious experience and practice, philosophy,

cognitive science, neuroscience, psychology, and

anthropology. Each of these fields may contribute to

neurotheology and conversely, neurotheology may

ultimately contribute in return to each of these fields.

Ultimately, neurotheology must be considered as a

multidisciplinary study that requires substantial

integration

of

divergent

fields,

particularly

neuroscience and religious phenomena. More

importantly, for neurotheology to be a viable field that

contributes to human knowledge, it must be able to

find its intersection with specific religious traditions.4

For instance, Islam is powerful, growing religion that

would seem to be an appropriate focus of

neurotheology. After all, if neurotheology is unable to

intersect with Islam, then it will lack utility in its

overall goal of understanding the relationship

between the brain and religion. Obviously, these

resulting changes of behavior would lead to a better

understanding or perception of the world around us

creating better harmonious, functional individuals,

who can be the driving force behind change and on a

larger scale of family and society as well.

Clearly, one of the initial problems with

neurotheology as a field is the exploitation of

neurotheology as a term. Too often, the term

neurotheology has been used inaccurately or

inappropriately.5 Many times, it appears to refer to a

study an idea that incorporates neither neuroscience

nor theology. Strictly speaking, neurotheology refers

to the field of scholarship linking the broad categories

of both neurosciences and theological studies.

Neuroscience would thus refer to the empirical study

of the central nervous system or 'brain and theology';

would refer to the critical and rational analysis of a

particular religious belief system, pertaining to God. It

may also constitute a robust "natural theology of the

brain".6 Of course, both the terms neuroscience and

theology have evolved over time.

Iranian Journal of Neurology 2014

Corresponding Author: Alireza Sayadmansour

Email: ijnl@tums.ac.ir

Email: sayadmansour@ut.ac.ir

http://ijnl.tums.ac.ir

4 January

Neuroscience used to imply the study of nerve

cells and their function without a clear regard for

behavioral and cognitive correlates. Neuroscience

today extends over many different fields including

cognitive neuroscience, neurology, neurobiology of

spirituality, psychiatry and psychology, and

sociology. The tools have also become much more

advanced, including a variety of brain imaging

capabilities, for exploring the relationship between the

brain and various cognitive, emotional, and

behavioral processes (i.e. "photographs of God"7).

Theology has also changed over time. In a very strict

sense, theology is the study of God. Thus, the word

theology should be reserved for theistic religions

only, and even more specifically, from, those arising

out of the Abrahamic traditions. Both JudaeoChristian and Islamic theologians are divided among

themselves about whether to integrate philosophy

into their theologies, or to base their theologies solely

upon their scriptures.

For neurotheology to be a viable field, it most

likely should not be limited to only neuroscience and

theology. In reconsidering the term neurotheology

then, it seems appropriate to allow for expanded uses

of the neuro component and the theology

component. It would seem appropriate for

neurotheology to refer to the totality of religion and

religious experience as well as theology. This ability to

consider, in a broad scope, all of the components of

religion from a neuroscientific perspective would

provide neurotheology with an abundant diversity of

issues and topics that can ultimately be linked, under

one heading. On the other hand, if the target of study

encompasses so many aspects of religion and

spirituality, the field might become so broad that it

loses its ability to say something unique about

religious and spiritual phenomena.

Brain functions and theological topics

In this section, I will examine a variety of overarching

brain functions to determine how theological

concepts, in general, might be derived. It should be

emphasized that the brain functions described below

relate to broad categories of functions. Future

neurotheological scholarship will need to better

evaluate the specifics of different brain processes to

determine if and how they relate to religious and

theological concepts in general.8

The holistic function

The brain, especially the right hemisphere, has the

ability to perceive holistic concepts such that we

perceive and understand wholeness in things rather

than particular details. For example, we might

understand all the cells and organs to comprise the

whole human body. From a religious or spiritual

perspective, we might understand a concept of

Neurotheology: The relationship between brain and religion

absolute oneness as pertaining to God. Furthermore,

the holistic process in the brain allows for the

expansion of any religious belief or doctrine to apply

to the totality of reality, including other people, other

cultures, animals, and even other planets and galaxies.

In fact, as human knowledge of the extent of the

universe has expanded, the notion of God has

incorporated this expanding sense of the totality of the

universe. The holistic function pushes us to

contemplate that whatever new reaches of the

universe astronomers can find, God must be there. No

matter how small and unpredictable a subatomic

particle might be, God must be there, too.9

The quantitative function

In the most general sense, the quantitative processes

of the brain help to produce mathematics and a

variety of quantitative-like comparisons about objects

in the world. The quantitative function clearly both

underlies and supports much of science and the

scientific method.10 Science essentially is based upon a

mathematical description of the universe. In terms of

philosophical and theological implications, the

quantitative function appears to have heavily

influenced the ideas of philosophers such as

Pythagoras who often used mathematical concepts

such as geometry to help explain the nature of God

and the universe.

A potentially interesting application of the

quantitative function is in the evaluation of the strong

emphasis on certain special numbers used in religious

traditions. For example, specific numbers abound in

the bible such as the number 40 (40 days and nights of

the flood; the Jews wandered the desert for 40 years,

etc.) and lend their significance in terms of time,

people, and places. Islam also makes use of special

numbers in the Quran and in the doctrines that follow

from it. According to Shiism, there are the Ten

Ancillaries of the Faith (Sunnis believe in the Five

Pillars of Islam and the Six Articles of Belief); and the

99 attributes of Allah. One might ask if these numbers

provide additional meaning within our brain. Is it

easier for us to believe in or comprehend these

concepts when presented along with a specific

number? We know that our brain has a great interest

in numbers and generally likes to utilize them. This

quantitative process might strengthen our belief in

anything associated with numbers. And again, there

are special numbers such as 5, 10, 40, or 99, which

might strike a particular effect in the brain, a function

of the left hemisphere.

The binary function

The binary processes of the brain enable us to set

apart two opposing concepts. This ability is critical for

theology since the opposites that can be set apart

include those of good and evil, justice and injustice,

Iran J Neurol 2014; 13(1)

http://ijnl.tums.ac.ir

4 January

53

and man and God among many more.11 Many of these

polarities/dichotomies are encountered throughout

religious texts of all religions. Much of the purpose of

religions is to solve the psychological and existential

problems created by these opposites. Theology, then,

must evaluate the myth structures and determine

where the opposites are and how well the problems

presented by these opposites are solved by the

doctrines of a particular religion such as Islam. The

instructive styles of the Quran are often examples

juxtaposing the good and the bad.

The causal function

The ability of the brain to perceive causality is also

crucial to theology. When the causal processes of the

brain are applied to all of reality, it forces the question

of what is the ultimate cause of all things.12 This

eventually leads to the classic notion of St. Thomas

Aquinass Uncaused First Cause as an argument for

Gods existence. For monotheistic religions, the

foundational doctrines posit that God is the uncaused

cause of all things. However, this very question of how

something can be uncaused is a most perplexing

problem for human thought. In fact, theologians,

philosophers, and scientists have tangled with causality

as integral to understanding the universe and God.

Aristotelian philosophy postulated four aspects of

causality i.e. efficient causality, material causality,

formal causality, and final causality. The question of

causality thus became applied to God to determine

how, in fact, God could cause the universe.13

Willfulness and orienting functions

Two other important brain functions are related to the

ability to support willful or purposeful behaviors and

the ability to orient our self within the world.

Neuroscientifically, the willful function is regarded to

arise, in large part, from the frontal lobes.14 There is

evidence that frontal lobe activity is involved in

executive functions such as planning, coordinating

movement and behavior, initiating and producing

language. Evidence has also shown the frontal lobes to

become activated when an individual performs a

meditation or prayer practice in which there is intense

concentration on the particular practice.15

Reflections on neurotheology and neuroscience

There are a number of neuroscience topics that might

directly

influence

and

be

influenced

by

neurotheological research. One of the major issues

that neurotheology faces, is the problem of the ability

to determine the subjective state of the subject. This is

also a more universal issue in the context of cognitive

neuroscience.16 After all, one can never know precisely

what a research subject is thinking at the precise

moment of imaging. If you have a subject solving a

mathematical task, one does not know if the persons

mind wandered during the task. You might be able to

54

determine if they did the test correctly or incorrectly,

but that in and of itself cannot determine why they

were right or wrong. The issue of the subjective state

of the individual is particularly problematic in

neurotheology.17 When considering spiritual states,

the ability to measure such states empirically while

not disturbing such states is almost impossible. Hence,

it is important to ascertain as much as possible what

the

person

thinks

they

are

experiencing.

Neurotheology research can help better refine

subjective measurements. Spiritual and religious

states are perhaps the best described of all states and

thus, can be an important starting point for advancing

research in the measurement of subjective states.

Another area in which neurotheology could

provide important scientific information is in

understanding the link between spirituality and

health.18 A growing number of studies have shown

positive, and sometimes negative, effects on various

components of mental and physical health.19 Such

effects include an improvement in depression and

anxiety, enhanced immune system, and reduced

overall mortality associated with individuals who are

more religious. On the other hand, research has also

shown that those individuals engaged in religious

struggle, or who have a negative view of God or

religion, can experience increased stress, anxiety, and

health problems.20 Research into the brains responses

to positive and negative influences of religion might

be of great value in furthering our understanding of

the relationship between spirituality and health.

Finally, one of the most important goals of

cognitive neuroscience is to better understand how

human beings think about and interact with our

environment. In particular, this relates to our

perception and response to the external reality that the

brain

continuously

presents

to

our

deep

consciousness.21 Neurotheology is in the unique

position to be able to explore epistemological

questions that arise from neuroscience and theology.

Thus, integrating religious and scientific perspectives

might provide the foundation upon which scholars

from a variety of disciplines can address some of the

greatest questions facing humanity.

Conclusion

As an emerging field of study, neurotheology has the

potential to offer a great deal to our understanding of

the human mind, consciousness, scientific discovery,

spiritual experience, and theological discourse. In

particular, there are many potentially rich areas to

consider in the context of Islam. It should be

remembered that neurotheological scholarship must

tread carefully upon these topics and attempt to

develop clear, yet novel methods of inquiry. All

Iran J Neurol 2014; 13(1)

Sayadmansour

http://ijnl.tums.ac.ir

4 January

results of neurotheological scholarship must be

viewed and interpreted cautiously and within the

context of existing doctrine, beliefs, and theology.

However, if neurotheology is ultimately successful in

its goals, its integrative approach has the potential to

revolutionize our understanding of the universe and

our place within it. Better understanding of human

mind, its biology and neurocircuitry has the potential

to solve man-made problems. It can even create a

bridge between the empirical science of neurology

with the intangibility and sensitivities of theology.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

How to cite this article: Sayadmansour A.

Neurotheology: The relationship between brain and

religion. Iran J Neurol 2014; 13(1): 52-5.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Biello D. Searching for God in the Brain

[Online]. [cited 2013 June 15]; Available

from: URL:

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.c

fm?id=searching-for-god-in-the-brain

Newberg AB. Principles of Neurotheology.

Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing; 2010. p.

1-3.

Burton R. Neurotheology. In: Burton R,

editor. On Being Certain: Believing You

Are Right Even When You're Not. New

York, NY: St. Martin's Press; 2009.

Apfalter W. Neurotheology: What Can We

Expect from a (Future) Catholic Version?

Theology and Science 2009; 7(2): 163-74.

Newberg AB. Neuroscience and religion:

Neurotheology. In: Jones L, editor.

Encyclopedia of religion. 2nd ed. New York,

NY: Macmillan Reference USA; 2005.

Ashbrook JB, Albright CR. The humanizing

brain: where religion and neuroscience

meet. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim Press; 1997.

p. 7.

Newberg A, D'Aquili EG. Why God Won't

Go Away: Brain Science and the

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

Biology of Belief. New York, NY: Random

House Publishing Group; 2008. p. 12.

Alper M. God Part of the Brain. Naperville,

IL: Sourcebooks; 2008. p. 5.

D'Aquili EG, Newberg AB. The Mystical

Mind: Probing the Biology of Religious

Experience. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress

Press; 1999.

Wikipedia. Ibid [Online]. [cited 2008];

Available

from:

URL:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibid

Damasio AR. The Feeling of what Happens:

Body and Emotion in the Making of

Consciousness. San Diego, CA: Harcourt

Incorporated; 2000.

Brandta PY, Clmentb F, Re Manningc R.

Neurotheology:

challenges

and

opportunities. Schweizer Archiv Fur

Neurologie Und Psychiatrie 2010; 161(8):

305-9.

Hick J. The New Frontier of Religion and

Science:

Religious

Experience,

Neuroscience and the Transcendent. New

York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2010. p.

58-62.

McKinney LO. Neurotheology: Virtual

Neurotheology: The relationship between brain and religion

Iran J Neurol 2014; 13(1)

http://ijnl.tums.ac.ir

4 January

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

Religion in the 21st Century. Washington,

DC: American Institute for Mindfulness;

1994. p. 48.

Fontana D. Psychology, Religion and

Spirituality. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. p.

145-7.

Sim MK, Tsoi WF. The effects of centrally

acting drugs on the EEG correlates of

meditation. Biofeedback Self Regul 1992;

17(3): 215-20.

Crick F. Astonishing Hypothesis: The

Scientific Search for the Soul. New York,

NY: Scribner; 1995. p. 53.

Koenig H, King D, Carson VB. Handbook

of Religion and Health. Oxford, UK:

Oxford University Press; 2012.

Carter R. Exploring Consciousness.

Berkeley, CA: University of California

Press; 2004. p. 44-7.

King M, Speck P, Thomas A. The effect of

spiritual beliefs on outcome from illness.

Soc Sci Med 1999; 48(9): 1291-9.

Miller L. Chaos as the Universal Solvent

[Online]. [cited 2013]; Available from: URL:

http://asklepia.tripod.com/Chaosophy/chaos

ophy3.html

55

Вам также может понравиться

- Sustainability 10 00415Документ21 страницаSustainability 10 00415jorgemauriciocuartasОценок пока нет

- 1 Principles of PsychotherapyДокумент10 страниц1 Principles of PsychotherapyjorgemauriciocuartasОценок пока нет

- El Líder y La Fortaleza de La CooperaciónДокумент2 страницыEl Líder y La Fortaleza de La CooperaciónjorgemauriciocuartasОценок пока нет

- The Neurobiology of PleasureДокумент17 страницThe Neurobiology of PleasurejorgemauriciocuartasОценок пока нет

- Neurotheology PDFДокумент4 страницыNeurotheology PDFjorgemauriciocuartasОценок пока нет

- Geno SpiritualityДокумент18 страницGeno SpiritualityjorgemauriciocuartasОценок пока нет

- Rewireyourbrain 120203041805 Phpapp02Документ28 страницRewireyourbrain 120203041805 Phpapp02jorgemauriciocuartas100% (2)

- Psychotherapy in The Age of The ComputerДокумент6 страницPsychotherapy in The Age of The ComputerjorgemauriciocuartasОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- 1st Year Merit List 2018 (For Print) PDFДокумент138 страниц1st Year Merit List 2018 (For Print) PDFsaleemОценок пока нет

- Nazis, Arabs-Al-Qaueda-John LoftusДокумент7 страницNazis, Arabs-Al-Qaueda-John LoftusAmbassadoryedahsani100% (1)

- GossipДокумент2 страницыGossipLaila HabibОценок пока нет

- Doa SHLTДокумент4 страницыDoa SHLTCindy S MagaОценок пока нет

- Summer 2014 FinalДокумент64 страницыSummer 2014 FinalskimnosОценок пока нет

- Ahl Al-Bayt HadithsДокумент85 страницAhl Al-Bayt HadithsIsmailiGnosticОценок пока нет

- Why I Love Israel Based On The QuranДокумент7 страницWhy I Love Israel Based On The QuranYusuf (Joe) Jussac, Jr. a.k.a unclejoe100% (3)

- Crusades InteractiveДокумент18 страницCrusades InteractiveMiron Palaveršić100% (1)

- FSI Muda Periode 19Документ4 страницыFSI Muda Periode 19Abdul Haris Manggala PutraОценок пока нет

- Baby Khausar's StoryДокумент237 страницBaby Khausar's StoryMARYAM MUHAMMAD ZANWAОценок пока нет

- Iflas and Chapter 11 Classical Islamic Law and Modern BankruptcyДокумент27 страницIflas and Chapter 11 Classical Islamic Law and Modern BankruptcyManfadawi FadawiОценок пока нет

- Islamic Wonders.Документ17 страницIslamic Wonders.Junaid Mohsin0% (1)

- Difference Between Muslim's and Qadiani'sДокумент13 страницDifference Between Muslim's and Qadiani'sNasir AliОценок пока нет

- Measuring Religions with ScriptureДокумент92 страницыMeasuring Religions with ScriptureShohorab AhamedОценок пока нет

- Some Mistakes of Al-MawdudiДокумент3 страницыSome Mistakes of Al-MawdudisajjadinamdarОценок пока нет

- Iqob Ubudiyah Bulan November Ganjil 2023 2024Документ20 страницIqob Ubudiyah Bulan November Ganjil 2023 2024Rey NursyamsiОценок пока нет

- Understanding Ijma and its Role in Islamic JurisprudenceДокумент27 страницUnderstanding Ijma and its Role in Islamic JurisprudenceMahrukh SОценок пока нет

- The Blessed BasmalaДокумент8 страницThe Blessed BasmalaTAQWA (Singapore)90% (21)

- Data Sarpras MDTДокумент88 страницData Sarpras MDTEuis JuwitaОценок пока нет

- Abraj Al Bait PresentationДокумент13 страницAbraj Al Bait PresentationGrendelle BasaОценок пока нет

- Architectural Thesis for Inclusive Learning CentreДокумент89 страницArchitectural Thesis for Inclusive Learning CentreArnav Dasaur100% (3)

- Method of Establishing Khilafah - Anwar Al-AwlakiДокумент7 страницMethod of Establishing Khilafah - Anwar Al-Awlakiqislam57Оценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент40 страницUntitledapi-566091130% (1)

- The Signs of Qiyamat - DoomsdayДокумент7 страницThe Signs of Qiyamat - DoomsdayM Aamir Sayeed100% (4)

- Third Quarter Assessment: A. Islam's Holy Scripture: The KoranДокумент4 страницыThird Quarter Assessment: A. Islam's Holy Scripture: The KoranHezl Valerie ArzadonОценок пока нет

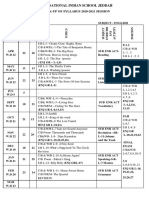

- Break-Up of Syllabus 2020-21 International Indian School JeddahДокумент20 страницBreak-Up of Syllabus 2020-21 International Indian School JeddahSyed Sabir AhmedОценок пока нет

- DeptalsДокумент4 страницыDeptalsnehllajacintoОценок пока нет

- Susunan Acara Wisuda EnglisДокумент3 страницыSusunan Acara Wisuda EnglisImam TurmudiОценок пока нет

- Notice HolydayДокумент4 страницыNotice HolydaySazidul Islam PrantikОценок пока нет

- Pakistani Novelists Explore Political and Social IssuesДокумент4 страницыPakistani Novelists Explore Political and Social Issuesbc070400339100% (2)