Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Woolfolk, R. - The Power of Negative Thinking

Загружено:

dengamer7628Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Woolfolk, R. - The Power of Negative Thinking

Загружено:

dengamer7628Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

\\Server03\productn\T\THE\22-1\THE102.

txt

unknown

Seq: 1

16-MAY-02

7:52

The Power of Negative Thinking:

Truth, Melancholia, and the Tragic Sense of Life

Robert L. Woolfolk

Princeton University

Abstract

In this brief essay I argue that the contemporary positive

psychology movement fails to emphasize important

aspects of human existence that are essential to human

excellence. Through an explication of some historical,

cross-cultural, and literary examples, I argue for the

importance of a kind of negative psychology that is fundamental to an adequate comprehension of the human

situation.

The advent of the contemporary positive psychology movement

inspires many reactions. One, inevitably, is that of plus c a change,

plus cest la meme

chose. Maybe its my age, my generational sensibilities at work here, but I was there for the previous version of positive psychology and to me that still seems like the genuine article. Of

course, even before the humanistic psychology movement there were

incarnations of positive psychology in America, the Emmanuel Movement, the New Thought, the imported mantras of Emile Coue.

Remember: Every day, in every way, I am getting better and better.

Americans have always been dedicated to self-improvement and had

little use for the tragic view of life. Indeed, American pop psychology

has always been an explicitly positive psychology. The Dale Carnegies,

Napoleon Hills, Werner Erhards, and Tony Robbinses of this world

vastly outnumber the champions of human potential we remember

from the 1960s. Even before the advent of contemporary positive psychology a few mainstream behavioral scientists had gotten involved.

There was David McClellands (1984) memorable project three

decades ago to export the American achievement ethos to the Indian

subcontinent, there offering a rather remarkable set of seminars for

indigenous executives (called achievement motivation training).

Although I cant claim to grasp all the nuances of the current positive

Correspondence concerning this article may be sent to: Robert L.

Woolfolk, 18 Turner Court, Princeton, NJ 08540. Email: woolfolk@

princeton.edu.

\\Server03\productn\T\THE\22-1\THE102.txt

20

unknown

Seq: 2

16-MAY-02

7:52

Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psy. Vol. 22, No. 1, 2002

psychology, I dont think this time around, its going to be very dionysian. No sex, no drugs, no rock and roll. It seems like you can explore

positive psychology wearing a coat and a tie or high heels and without

messing up your hair; it seems more a creature of the boardroom than

the hot tub.

Advocates of positive psychology from Maslow to Seligman have

suggested that psychology has been too focused on various negatives:

disease, disorder, and defect, but I would submit that American psychology, contrary to that claim, has failed to adequately appreciate the

importance of certain forms of negativity. I would submit negative

thinking is not only valuable, but indispensable, and suggest that we

give much too little attention to acknowledging, confronting,

accepting, and perhaps even embracing suffering and loss. I want to

suggest also that there may be worse things in life than experiencing

negative affect. Among those worse things are ignorance, banality,

credulity, self-deception, narcissism, insensitivity, philistinism, and isolation, all of which the program of positive psychology, as it is presently constituted, potentially seems to promote.

I shall not attempt a systematic or conclusive argument. There is not

space and I am not certain the thesis is subject to demonstration. In

lieu of argument, I shall confine myself to reporting some anecdotes,

the implications of which, I hope, will be clear. The first of these takes

us pretty far back. So hop in your imaginal time machines and lets go

back together. . .. .

Almost twenty five hundred years have passed since the Great King

of Persia, Xerxes, set out to wage war against the Greek city-states.

Xerxes war against the Greeks had, in addition to those economic and

political motives common to most wars, elements of vanity and of vengeance. Ten years earlier, Xerxes father Darius had sought to conquer

Greece but had underestimated his foe and suffered humiliating

defeat. But as the worlds reigning superpower in 480 B.C., the Persian

Empire ruled by Xerxes was regarded as militarily invincible.

The Great Kings sense of omnipotence likely was at its high point

when, arriving at the Hellespont commanding the largest army ever

assembled, he paused before crossing into Europe. Seated upon a

throne high above the multitude, Xerxes conducted a grand review of

his forces. Ships filled the waters and soldiers covered the land, as far

as the eye could see, and beyond. After a brief interval of self-congratulation, however, Xerxes began to weep profusely. He broke down.

When asked to explain his distress The Great King exclaimed

I was overcome with pathos, sadness at the thought that

even among all these thousands of men I behold, in one

hundred years, not one will be alive. (Herodotus, 1987, p.

486)

\\Server03\productn\T\THE\22-1\THE102.txt

The Power of Negative Thinking

unknown

Seq: 3

16-MAY-02

7:52

21

Now from the perspective of positive psychology something is

WRONG with this picture!!! Autocratic leader of the worlds greatest

empire, richest person on earth, 30-1 favorite in the upcoming war

against the Greeks, at the height of his powers, and this guy is telling us

that the paths of glory lead but to the grave. We sense the poor fellow

probably needs a therapist, or perhaps an executive coach. And in

timely fashion the narrator of this story, Herodotus, provides one in

the person of Xerxes uncle, Artabanus, who proceeds to tell him

though it is true enough that no one there will be alive in 100 years and

yes, thats a pity, but that the brevity of life is not its most regrettable

feature. He says

In ones life we have deeper sorrows to bear than that.

Short as our lives are, there is no human being either here

or elsewhere so fortunate that it will not occur to him,

often and not just once, to wish himself dead rather than

alive. For misfortunes fall upon us and sicknesses trouble

us, so that they make this life, for all its shortness, seem

long. (Herodotus, 1987, p. 486)

Now this is some therapy!

We, who like Herodotus, know how this story turns out that the

war will be a disaster for Xerxes and the Persians recognize the

tragic resonances in Artabanuss downbeat approach, and understand

that it befits the baneful future it portends. He belongs to an

unfashionable school of therapy. This is therapy of the old school,

Greek therapy, as practiced by Herodotus, Sophocles, and Socrates.

Its aim is a kind of Delphic self-knowledge, sophrosyne, a Greek word

that is refractory to translation, but one meaning of which is the knowledge that people have about themselves, individually and collectively,

especially as that knowledge reveals human shortcomings and limitations, especially hubris and hamartia (North, 1966; Woolfolk, 1998).

Self-knowledge has value because it allows us to promote what is best

in ourselves and to minimize what is worst. It is prerequisite to and an

essential part of virtue, excellence, the good life. From it we do not

automatically derive pleasure or psychological well-being (Robinson,

1997).

If all this doesnt sound much like what is stressed in the contemporary positive psychology movement, it is because it isnt. Actually, it

turns out that many of the individuals we admire most were negative

thinkers, if not depressives. Many of the most important products of

Western civilization have required negative thinking. In other times

and places, great cultures incorporated in their worldviews elements of

what I am calling negative psychology. We, of course, can find nonWestern world views, as well, that accentuate the negative a bit more

than do the authors of recent APA policy initiatives. Perhaps the obvious example of such a worldview is that of Buddhism.

\\Server03\productn\T\THE\22-1\THE102.txt

22

unknown

Seq: 4

16-MAY-02

7:52

Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psy. Vol. 22, No. 1, 2002

Buddhism begins, famously, with a declaration of the existence of

pervasive human discontent and misery, misery that is universal and

not limited to retributive consequences for the iniquitous or to maladies of the unfortunate. Buddhas First Noble Truth which forms the

foundation for the Buddhist Weltanschauung, is that consciousness in

interaction with the universe inevitably entails dukkha (and its Tibetan

counterpart sduk-bsngal),

often translated as suffering but also as pain,

sorrow, unhappiness, dysfunctionality, dissatisfaction, frustration,

angst, and even stress. Dukkha is ubiquitous, persistent, and unavoidable. From a Buddhist standpoint, it is not a cognitive distortion to

see the world and human existence as dangerous, unsatisfying, painful,

and meaningless; rather it is irrational not to see the world this way.

Such negative appraisals can be thought of as the beginning of wisdom

(King & Woolfolk, 2001).

Buddhism adopts this pessimistic outlook toward the availability of

happiness in the natural course of human existence, because Buddhists

believe that the world and human beings are simply not designed such

that happiness or even satisfaction will be the normal lot of people; but

rather that unhappiness and dissatisfaction will be the normal and natural condition. Some contemporary Buddhist scholars have argued

that Buddhism or Buddhist societies may consider as normal reactions some of the psychological symptoms of depression, such as

hopelessness and despondency, that Western psychiatry would consider to be despair of pathological proportions. For example the

anthropologist, Obeyesekere, writing about the Buddhist culture of Sri

Lanka, suggested that when examining many features of depression:

I would say we are not dealing with a depressive but a

good Buddhist. The Buddhist would take one further step

in generalization: it is not simply the general hopelessness

of ones own lot; that hopelessness lies in the nature of

the world, and salvation lies in understanding and overcoming that hopelessness. . .If [Buddhists]. . . are afflicted

by bereavement and loss. . ., they can generalize their

despair from the self to the world at large and give it Buddhist meaning and significance. (1988, p. 140)

The Buddhists are not the only non-Westerners who are negative

thinkers. Muslims, in general, see grief, sadness, and other dysphoric

emotions as concomitants of religious piety and correlates of the painful consequences of living justly in an unjust world. The ability to

experience sorrow is regarded a mark of depth of personality and

understanding. In Iran, for example, sadness, grief, and despair are

central to the Iranian ethos. Sadness for Iranians is associated with

maturity and virtue. A person who expresses happiness too quickly

often is considered socially incompetent (Good, Good, & Moradi,

1985).

\\Server03\productn\T\THE\22-1\THE102.txt

The Power of Negative Thinking

unknown

Seq: 5

16-MAY-02

7:52

23

The experience of sadness is valued also in Japan. There during the

Tokugawa period, roughly between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries (1603-1868), one of the principal cultural projects of Japanese historians and literary scholars was that of interpreting ancient Japanese

texts with the aim of identifying essential aspects of Japanese national

character. Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801) fashioned the concept of

mono no aware, sometimes translated as the persistent sadness that

inheres in all things. This concept was postulated to define an essential ingredient of Japanese culture and meant to characterize both a

certain aesthetic and a capacity to understand the world directly,

immediately, and sympathetically (Masahide, 1984). Mono no aware

was thought to distinguish Japanese culture and mark its superiority to

foreign forms of apprehension. The idea here is that of a sensitivity

that involves being touched or moved by the world. This kind sensitivity to the world is thought to be inextricably intertwined with a capacity to experience the sadness and pathos that emanates from the

transitory nature of things.

In the history of the West recognitions of the benighted nature of

human existence are seen in many places: the doctrine of original sin,

the contrast between the divine and the worldly, Stoic philosophy, and

in the popular culture of the Late Middle Ages. Also in the West a

commonly held view is that intelligence, creativity, and moral sensitivity are associated with melancholy. Aristotle, famously in the

Problemata, wondered why all philosophers seemed to be melancholic.

This query prefigures the Renaissance view that the cultivated individual inevitably will possess a melancholy temper, a proposition that

foreshadows the contemporary evidence that depression and

dysphoria, and hyperawareness of the sorrow of the world, are linked

to genius. Shakespeare, as he does so often provides the prototype, one

that in the context of the present discussion raises a question. Why is

Hamlet so compelling to us, so irresistible? Why do we regard him the

greatest creation of our greatest literary master? And let me provide a

hint, its not because he is able to elevate his mood through the application of psychological techniques.

Hamlet doesnt put a positive spin on things. He is too intellectually

acute, too ironically perceptive to accept an artifice that might alleviate

his distress. Characterologically speaking, we dont know whether his

melancholy and his nihilism emanate from a hypertrophy of intellectual consciousness, or rather from its apotheosis. But we are convinced that Hamlet sees the truth, faces it, and articulates it with

unsurpassed eloquence. He understands that facet of human finitude

that Herodotus has Xerxes enunciate at the Hellespont; he understands that and much more. Nietzsche (1873/1968) thought that Hamlet had peered into the essence of things, perceiving the horrible truth

that

\\Server03\productn\T\THE\22-1\THE102.txt

24

unknown

Seq: 6

16-MAY-02

7:52

Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psy. Vol. 22, No. 1, 2002

Our wills and fates do so contrary run

That our devices still are overthrown:

Our thoughts are ours, their ends none of our own.

Of course, the proponent of positive psychology here might rebut

that no one really cares about a bunch of lugubrious European philosophizing or a lot of Eastern ideas that may have begun as rationalizations for the discontents of overpopulated, collectivist societies. This is

America, not only the capital of psychology but the birthplace of the

new economy, engine of global capitalism. Were postindustrial, third

wave. There are no limits. Nothing can stop the growth of the global

information economy. Right? What a difference a year or two can

make in such a view. But even with the NASDAQ crash and the chilling effects of terrorism, all in all, this is the land of opportunity, of

self-improvement, and of positive thinking. Historically, Americans

have been optimists and antagonistic to some of the tragic views mentioned here. But we have, at times, produced our share of negative

thinking. Oddly enough, Tocqueville wrote that

In America I saw the freest and most enlightened men,

placed in circumstances the happiest to be found in the

world; yet it seemed to me as if a cloud habitually hung

upon their brow, and I thought them serious and almost

sad even in their pleasures. (Tocqueville, 1840/1969, p,

536)

Hey Ill go Alexis one step further: To some extent it was negative

thinkers that built America. Let me illustrate with a couple of

examples.

Our first example of an American negative thinker, is one who perhaps derives his negativity from being, one of Americas early graduate

students. He was Princetons first grad student, as folks around Nassau

Hall will tell you proudly. This man was known for his careful readings

of the classics and the Enlightenment writers. But he was also a student of Hobbes and Machiavelli, and absorbed their skepticism and

realism.

Human beings he wrote are inflamed with mutual animosity, and

are . . . much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to cooperate for their common good. (Madison, (1787/1961, Federalist 10).

He believed that a problem with democracy is that it would be the

interest of the majority in every community to despoil and enslave the

minority of individuals (Madison, 1865, pp. 250-251) and If men

were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to

govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government

would be necessary. But in the real world he continued, ambition

must be made to counteract ambition (Madison, 1787/1961, Federalist

\\Server03\productn\T\THE\22-1\THE102.txt

unknown

Seq: 7

16-MAY-02

The Power of Negative Thinking

7:52

25

51). In essence democratic republics had to be protected from those

vices endemic to human nature.

So James Madison, the father of our constitution was able to peer

into the darkness of the human heart and not blink. The American

experiment succeeded as well as it has, in part, because Madisons negative psychology generated the U. S. Constitutional framework with its

protections, checks, and balances that structure and constrain the

potential abuses of democracy.

The person who perhaps saved the American experiment was one so

tender-hearted that he could not discipline his children, could not

reject a lover, and once was completely unnerved by the sight of a baby

bird that had fallen from its nest (Wilson, 1998). Abraham Lincoln

tried a bit of positive psychology on himself in the form of jokes and

stories, told with such skill that he developed a reputation as a humorist and a raconteur. But he was fundamentally a sorrowful man. He

confessed to his law partner William Herndon, if it were not for these

stories jokes jests I should die: they give vent are the vents of

my moods and gloom. (quoted in Burlingame, 1994, p. 106). His

favorite poem was a doleful lament by William Knox entitled

Mortality:

Yea, hope and despondency, pleasure and pain,

Are mingled together in sunshine and rain:

And the smile and the tear, the song and the dirge,

Shall follow each other like surge upon surge.

In many ways he was like Hamlet, suffering from what he described

as the intensity of thought, which will sometimes wear the sweetest

idea thread-bare and turn it to the bitterness of death. (quoted in

Oates, 1984, p. 37). A neighbor said that melancholy dripped from

him. After one of the losses that permeated his life, an observer commented that she had never seen a man so bowed down by grief. He

himself once said if theres a worse place than hell, Im in it (quoted

in Burlingame, 1994, p. 105).

Yet he may have been the greatest man our nation has produced and

as it was with Hamlet, his greatness derives directly from his capacity

to engage, comprehend, assimilate, and express the great sorrows of

this world. As a young man Lincoln had traveled in the South and

there witnessed the atrocities of slavery. The image of human beings

chained to each other never left him and was a continual source of

agitation. His great heart ached for those whose lives were so

wretched. He later remarked that if slavery is not wrong then nothing

is wrong.

Now the positive psychologist might counter, But Abraham Lincoln was a depressive, just think of what he could have accomplished

with a little positive thinking with a less depressogenic cognitive style.

\\Server03\productn\T\THE\22-1\THE102.txt

26

unknown

Seq: 8

16-MAY-02

7:52

Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psy. Vol. 22, No. 1, 2002

One might as well suggest that Hamlet would have been a better play

if the Prince had been able to effect a positive reframing of his complicated family dynamics. Lincolns intellectual acuity and his moral grandeur are inseparable from his unflinching relation to the pain of life.

His nation had engendered an internecine perdition. Lincolns comprehension of that national condition is on display most notably in the

second inaugural, in which he was able to apprehend and articulate the

meaning of the Civil War through those memorable, dreadful images

and analogies that could occur only to a negative thinker.

The negative psychology I have described and recommended here

is not so much an antipode to contemporary trends in psychology as it

is the description of another dimension or perhaps the exposition of an

existential background. Arguing about whether we are better off studying health or sickness, strength or weakness, in some sense, oversimplifies psychology and makes it one-dimensional. If psychology is to

avoid a banal and prosaic delimitation, it would be well advised to take

heed of some ancient and cross-cultural sources that give prominence

to the tragic, finite, and negative aspects of human existence.

References

Burlingame, M. (1994). The inner world of Abraham Lincoln.

Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Good, B. J., Good, M., & Moradi, R. (1985). The interpretation of

dysphoric affect and depressive illness in Iranian culture. In Kleinman, A., & Good, B. J. (Eds.), Culture and depression: Studies in

the anthropology and cross-cultural psychiatry of affect and disorder. (pp. 369-428). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Herodotus. (1987). The history. (D. Grene, Trans.). Chicago: The

University of Chicago Press.

King, A. & Woolfolk, R. L. (2001). Melancholia East and West. Paper

presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the

Advancement of Philosophical Psychopathology, New Orleans,

May, 2001.

Madison, James. (1961). Federalist No. 10. In The Federalist Papers, by

Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, ed. Jacob E.

Cooke. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. (Original

work published 1787)

Madison, James. (1961). Federalist No. 51. In The Federalist Papers, by

Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, ed. Jacob E.

Cooke. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press (Original

work published 1787)

Madison, J. (1865). Letter to James Monroe, Oct 5th, 1786 Madison,

James. 1865. Letters and Other Writings of James Madison, Published by order of Congress. 4 volumes. Edited by Philip R.

Fendall. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

\\Server03\productn\T\THE\22-1\THE102.txt

The Power of Negative Thinking

unknown

Seq: 9

16-MAY-02

7:52

27

Masahide, B. (1984). Religion and society in the Edo period as

revealed in the thought of Norinaga, Motoori. Modern Asian

Studies, 18, 581-592.

McClelland, D. C. (1984). Motives, personality, and society: Selected

papers. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Nietzsche, F. (1968). Birth of tragedy. Trans, W. Kaufmann in Basic

Writings of Nietzsche. New York. Random House, (Original work

published 1873)

North, H. (1966). Sophrosnye, self-knowledge and self-restraint in

Greek literature. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Oates, S. B. (1984). Abraham Lincoln: The man behind the myths.

New York: Harper and Row.

Obeyesekere, G. (1988). Depression, Buddhism, and the work of culture in Sri Lanka. In Kleinman, A., & Good, B. (Eds.), Culture

and depression: Studies in the anthropology and cross-cultural psychiatry of affect and disorder. (pp. 134-152). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Robinson, D. N. (1997). Therapy as theory and as civics. Theory and

Psychology, 7, 675-681.

Tocqueville, A de. (1969). Democracy in America (G. Lawrence,

Trans. J. P. Mayer, Ed.). New York: Doubleday Anchor. (Original

work published 1840).

Wilson, D. L. (1998). Honors voice: The transformation of Abraham

Lincoln. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Woolfolk, R. L. (1998). The cure of souls: Science, values, and psychotherapy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Thirty Years of Research On The Holodomor, A Balance SheetДокумент14 страницThirty Years of Research On The Holodomor, A Balance Sheetdengamer7628Оценок пока нет

- (2003) Clair - The Changing Story of Ethnography (Expressions of Ethnography)Документ24 страницы(2003) Clair - The Changing Story of Ethnography (Expressions of Ethnography)dengamer7628Оценок пока нет

- Fu, Pei Mei - Pei Mei's Chinese Cookbook Volume IДокумент185 страницFu, Pei Mei - Pei Mei's Chinese Cookbook Volume Idengamer7628100% (7)

- Billies Bounce Andreas ObergДокумент3 страницыBillies Bounce Andreas ObergSharad Joshi100% (1)

- Pre-Calculus PrerequisitesДокумент146 страницPre-Calculus PrerequisitesJean Gardy ClerveauxОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Itc LimitedДокумент64 страницыItc Limitedjulee G0% (1)

- Fast FashionДокумент9 страницFast FashionTeresa GonzalezОценок пока нет

- E61 DiagramДокумент79 страницE61 Diagramthanes1027Оценок пока нет

- READING 4 UNIT 8 Crime-Nurse Jorge MonarДокумент3 страницыREADING 4 UNIT 8 Crime-Nurse Jorge MonarJORGE ALEXANDER MONAR BARRAGANОценок пока нет

- Rooftop Rain Water Harvesting in An Educational CampusДокумент9 страницRooftop Rain Water Harvesting in An Educational CampusAkshay BoratiОценок пока нет

- Soil Biotechnology (SBT) - Brochure of Life LinkДокумент2 страницыSoil Biotechnology (SBT) - Brochure of Life Linkiyer_lakshmananОценок пока нет

- Compartment SyndromeДокумент14 страницCompartment SyndromedokteraanОценок пока нет

- Outlook 2Документ188 страницOutlook 2Mafer Garces NeuhausОценок пока нет

- 17-003 MK Media Kit 17Документ36 страниц17-003 MK Media Kit 17Jean SandiОценок пока нет

- Method StatementДокумент29 страницMethod StatementZakwan Hisyam100% (1)

- SanMilan Inigo Cycling Physiology and Physiological TestingДокумент67 страницSanMilan Inigo Cycling Physiology and Physiological Testingjesus.clemente.90Оценок пока нет

- Riber 6-s1 SP s17-097 336-344Документ9 страницRiber 6-s1 SP s17-097 336-344ᎷᏒ'ᏴᎬᎪᏚᎢ ᎷᏒ'ᏴᎬᎪᏚᎢОценок пока нет

- Epicor Software India Private Limited: Brief Details of Your Form-16 Are As UnderДокумент9 страницEpicor Software India Private Limited: Brief Details of Your Form-16 Are As UndersudhadkОценок пока нет

- Neuro M Summary NotesДокумент4 страницыNeuro M Summary NotesNishikaОценок пока нет

- REV Description Appr'D CHK'D Prep'D: Tolerances (Unless Otherwise Stated) - (In)Документ2 страницыREV Description Appr'D CHK'D Prep'D: Tolerances (Unless Otherwise Stated) - (In)Bacano CapoeiraОценок пока нет

- 7-Multiple RegressionДокумент17 страниц7-Multiple Regressionحاتم سلطانОценок пока нет

- Benzil PDFДокумент5 страницBenzil PDFAijaz NawazОценок пока нет

- Heteropolyacids FurfuralacetoneДокумент12 страницHeteropolyacids FurfuralacetonecligcodiОценок пока нет

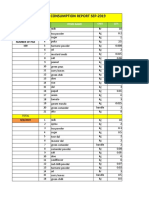

- Daily Staff Food Consumption Reports Sep-2019Документ4 страницыDaily Staff Food Consumption Reports Sep-2019Manjit RawatОценок пока нет

- Birding The Gulf Stream: Inside This IssueДокумент5 страницBirding The Gulf Stream: Inside This IssueChoctawhatchee Audubon SocietyОценок пока нет

- 3 Activities For Adults To Practice Modeling SELДокумент10 страниц3 Activities For Adults To Practice Modeling SELDavid Garcia PerezОценок пока нет

- TraceGains Inspection Day FDA Audit ChecklistДокумент2 страницыTraceGains Inspection Day FDA Audit Checklistdrs_mdu48Оценок пока нет

- Comparison and Contrast Essay FormatДокумент5 страницComparison and Contrast Essay Formattxmvblaeg100% (2)

- Business Plan Example - Little LearnerДокумент26 страницBusiness Plan Example - Little LearnerCourtney mcintosh100% (1)

- Scope: Procter and GambleДокумент30 страницScope: Procter and GambleIrshad AhamedОценок пока нет

- 107 2021 High Speed Rail Corridor RegДокумент3 страницы107 2021 High Speed Rail Corridor Rega siva sankarОценок пока нет

- 208-Audit Checklist-Autoclave Operation - FinalДокумент6 страниц208-Audit Checklist-Autoclave Operation - FinalCherry Hope MistioОценок пока нет

- API 510 Practise Question Nov 07 Rev1Документ200 страницAPI 510 Practise Question Nov 07 Rev1TRAN THONG SINH100% (3)

- 204-04B - Tire Pressure Monitoring System (TPMS)Документ23 страницы204-04B - Tire Pressure Monitoring System (TPMS)Sofia AltuzarraОценок пока нет

- Brody2012 PDFДокумент13 страницBrody2012 PDFfrancisca caceresОценок пока нет