Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Contracts I I

Загружено:

pppИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Contracts I I

Загружено:

pppАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

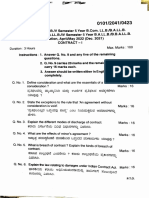

Contracts II

Contracts II

Introduction

This lecture looks at some important ways in which equity intervenes to modify our

understanding as to how promises to create or transfer an interest in land can come into being.

First, it looks at the law of part performance; here equity makes a valid contract enforceable

even though the requirements of section 3(1) of the Conveyancing and Property Ordinance

have not been complied with. Second, we will look at how estoppel (especially proprietary

estoppel) can give effect to promises to give someone an interest in land even though the

promise is neither contractually enforceable nor contained in a will. Finally, we will see the effect

of the rule in Walsh v Lonsdale to the effect that an enforceable contract concerning an estate in

land takes immediate effect in equity. We will also consider the constructive trust that exists

once an enforceable contract has been entered into.

Part performance

Section 3(1) of the Conveyancing and Property Ordinance requires that there should either be a

written contract or a written memorandum signed by the party to be charged. Section 3(1) is

concerned not with validity but with enforceability (with the question as to whether or not it will

be possible to bring an action to enforce the contract); it is possible to have a concluded oral

contract which is valid but not enforceable; the contract has truly come into existence, and

creates contractual rights and duties, but the court will not offer any assistance to enforce the

contract in the event of breach. An oral contract for the sale or disposition of an interest in land

might, however, be enforceable in equity if supported by sufficient acts of part performance

even though the requirements of section 3(1) have not been complied with. Section 3(2) of the

Conveyancing and Property Ordinance provides that section 3(1) does not affect the law

relating to part performance. This exception to section 3(1) is said to be justified in cases where

insistence on it would mean that the statutory provision was being used as an instrument of

fraud. 1 A vendor might, for example, agree orally to sell land and allow the purchaser into

possession to improve the land without any contract or memorandum complying with section

3(1) and before any formal conveyance has been executed. It might then be unconscionable for

Steadman v Steadman [1976] AC 536 at 540 per Lord Reid.

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

the seller to be allowed to rely on the statute to escape from the contract. Specific performance

can be awarded.

Steadman v Steadman,2 is one of the most important decisions on the law of part performance.

In this case, the parties' marriage had broken down. The wife had applied for a declaration that

the matrimonial home was jointly owned and an order for sale. The husband was making

maintenance payments to the wife and he had applied for a variation of the maintenance order.

Negotiations took place at the door to the courtroom and it was agreed that the wife would sell

her interest in the house to her husband for 1500 pounds. He also agreed to pay 100 pounds in

respect of arrears of maintenance payments. The agreement was explained to the court which

made orders implementing what the parties had agreed concerning maintenance. The husband

paid the 100 pounds and his solicitors prepared a deed to transfer the wife's interest in the

house to the husband. The wife, however, refused to sign the deed and relied on the English

equivalent of section 3(1) of the Conveyancing and Property Ordinance. The husband argued

that she had to to transfer her interest in the matrimonial home to him since there had been acts

of part performance of the oral agreement. The husband succeeded. In essence, the House of

Lords held that part performance is available where to the defendants knowledge, the plaintiff

has carried out some act or acts of pointing on the balance of probabilities to some contract

such as that alleged. Once this requirement has been satisfied, the court will hear oral evidence

to prove the terms of the contract.3

Steadman v Steadman is important because of the explanation that it gives about the operation

of the law in this area. The balance of probabilities test means that the existence of the alleged

contract need not be the only possible explanation for the actions relied upon; the alleged

contract only needs to be the most probable explanation for the actions. There was some

inconsistency of view between the members of the House of Lords as to whether the acts relied

on had merely to point to the existence of a contract or whether they had to point specifically to

the existence of a contract concerning land. The majority were of the view that it was enough

that the acts pointed to the existence of some contract such as that alleged, while Lord Salmon

thought that the acts should point specifically to the existence of a contract concerning an

interest in land.In Re Gonin, 4 Walton J. expressed the obiter view that the act of part

2

[1976] AC 536.

Steadman v Steadman [1976] AC 536.

4

[1979] Ch. 16.

3

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

performance should point to the existence of a contract concerning land. Since, on any view, the

act relied upon must point to the existence of a concluded contract, actions that are preparatory

to the formation of a contract are not sufficient.5 Instructing a solicitor to prepare a draft contract

is an example of a preparatory act that does not amount to part performance.

In Wu Koon Tai v Wu Yau Loi6 a lease of land in the New Territories was granted to Wu Cheong

U. He died and, in 1934, his son sold the land. In accordance with Chinese customary law the

sale was effected through a document signed by neither party but by a middleman. The

purchaser paid the price and went into possession. He and his successors remained in

possession. The successor-in-title of the grandson of the seller claimed to be entitled to the land.

Among other grounds relied on were the fact that there was no contract for sale satisfying

section 3(1) of the Conveyancing and Property Ordinance since the document had not been

signed by the parties or their authorised repesentative. Lord Browne-Wilkinson held that

payment of the purchase price and giving possession were the clearest acts of part

performance. Thus there was a specifically enforceable contract. In Rawlinson v Ames,7 the

defendant had entered into an oral contract to take a lease of property from the plaintiff. At the

defendants request, the plaintiff carried out alterations to the property. When the defendant

sought to withdraw from the transaction, it was held that the alterations amounted to acts of part

performance. In Wakeham v MacKenzie,8 a woman helped an old, infirm man whose wife had

just died. He asked her to give up her flat and live in a room in his flat, pay for her own food and

fuel and work for him without pay. In return, he orally agreed that he would leave his house to

her in his will. It was held that there was a contract and that the womans actions amounted to

acts of part performance.

Part performance only comes into play where a contract exists but is not enforceable because

of a failure to comply with section 3(1). So if the parties have not moved beyond the negotiation

stage then part performance is irrelevant. This is illustrated by the decision of the Court of Final

Appeal in World Food Fair Ltd v Hong Kong Island Development Ltd.9 Here the parties had

been negotiating for the grant of a lease of space in a shopping mall in Tsim Sha Tsui to be

used as a restaurant and food court. The parties had agreed many of the main terms in the

5

Shun Lin Weaving Factory Ltd v Siu Cheng Yee Wah Eva [1980] HKC 605.

[1996] 2 HKLR 477.

7

[1925] Ch. 96.

8

[1968] 1 W.L.R. 1175.

9

[2007] 1 HKLRD 498, CFA.

6

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

course of their negotiations. A draft letter of intent and tenancy agreement had been sent to the

tenants but had never been signed and the latter failed to record accurately what had been

agreed. Thinking that the negotiations would succeed, the would-be tenants paid an initial

deposit and (with the owner's consent) spent a large sum of money on construction works to

make the space ready for its intended use. Then the negotiations broke down. Ribeiro PJ

explained that the negotiations had not resulted in a contract at all since there was no

agreement as to the start date of the lease and the rent-free period (an element of the overall

rent calculation) nor as to the length of term to be granted pursuant to the option to renew that

would be contained in the lease. There was no contract at all and so part performance was

irrelevant.

Englands Reform: the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989

The English law concerning the formalities for land contracts and the doctrine of part

performance were previously the same as in Hong Kong. Then, the English Law Commission

produced a Report10 that was severely critical of the uncertainty inherent in these provisions. As

a result, England and Wales moved to a new regime under which contracts would only be valid

if they were in writing and signed by both parties.11 There is no sign, however, of any call for

Hong Kong to undertake a similar reform.

Proprietary estoppel

Introduction

The essential elements of a proprietary estoppel claim are:

1. a representation or assurance given by A to B that B will acquire As interest in land (or

some right over that land);

2. reasonable reliance by B on the expectation created by that representation or assurance;

3. some detriment to B caused by that reliance which makes it unconscionable for A to be

allowed to simply fail to give effect to Bs expectation.

10

11

Transfer of Land. Formalities for contracts for sale etc of land. Law Com. No. 164.

Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989, s.2(1).

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

A must have encouraged or allowed B to entertain a belief to Bs detriment so that it would be

unconscionable for A to be allowed to deny the truth of that belief. It does not matter that in so

acting A was mistaken as to his own rights in the matter (though this may affect the question of

unconscionability). B must be acting in reliance on As action (or inaction).12

Examples of proprietary estoppel

In Crabb v Arun District Council13 an assurance that a landowner would be granted a right of

access onto the neighbouring road owned by the Council was effective despite the parties'

awareness that the agreement in principle would need to be made firmer (by agreeing on details

such as payment) and would need to be incorporated in a deed or contract. Subsequent

conduct (building a gate in the agreed position and watching while Crabb sold part of his land

leaving the retained land reliant on the access agreed upon) both illustrated that the parties'

thought that there was a firm agreement and amounted to a representation in its own right.

Representations made during contractual negotiations: proprietary estoppel and subject to

contract

Provided it is clear that it is intended to be relied upon, a statement made in the course of

contractual negotiations can be a representation for the purposes of proprietary estoppel.

Where, however, it is clear that the parties are still negotiating then there is no basis for a

proprietary estoppel claim.14 This is because, the representation must be such as to engender a

confident expectation arising out of the common understanding of the parties (rather than a

mere hope) of obtaining a proprietary interest in land.15 The Privy Council decision in AttorneyGeneral v Humphreys Estate (Queen's Gardens) Ltd16 is one of the most important judgments in

this area. The Hong Kong Government had agreed with Humphrey's Estate (part of Hong Kong

Land or 'HKL') that there would be an exchange of land. Humphrey's Estate was to be granted a

Crown lease of Queen's Gardens and the right to develop it. In return, they were to transfer

some flats in another development to the Government and to make a balancing payment of over

12

Taylors Fashions Ltd v Liverpool Victoria Trustees Co Ltd [1982] Q.B. 133.

[1976] Ch. 179, CA (Eng).

14

Attorney-General v Humphreys Estate (Queens Gardens) Ltd [1987] HKLR 427, PC; Cobbe v

Yeomans Row Management Ltd [2008] 1 W.L.R. 1752, HL..

15

Cobbe v Yeomans Row Management Ltd [2008] UK HL 55 per Lord Walker of Gestingthorpe.

16

[1987] HKLR 427.

13

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

HK$100 million. The agreement was subject to contract but the payment was made and the

building on Queen's Gardens was demolished. Agreement on the relevant details had been

reached but communications between the parties, as well as internal Government

communications, made it clear that each party still proceeded on the basis that it was free to

back out of the transaction. HKL then withdrew from the negotiations. The Government claimed

that it could not do so because it was bound by an estoppel. The Governments claim failed. Its

own acknowledgement to itself that the arrangement was truly subject to contract and that

either party could back out was fatal in several respects: there was neither an assurance, nor

reliance.17 It was not unconscionable for HKL to take the Government at its word and view the

arrangement as still being subject to contract. Lord Templeman did not rule out the possibility

that the courts might find either that a contract had been formed or that an estoppel had arisen

despite the fact that the parties were negotiating subject to contract. He thought, however, that

such a finding would be a rare occurrence.18

The House of Lords decision in Cobbe v Yeoman's Row Management Ltd19 looked again at the

conditions to be met if a proprietary estoppel claim is to be successful. In particular, it

emphasises the need for the claimant to be ascertaining a clearly ascertainable proprietary right;

this will not be the case where reliance is being placed on statements made in the course of

negotiations that did not result in a concluded contract. Mr Cobbe (a property developer) had

agreed with Yeoman's Row Management Ltd (YRML) that he would get planning permission for

the development of a property owned by YRML. When that had been achieved the property

would be transferred to him. He would carry out the development works and the profits from the

sale of the property above an agreed sale price would be shared between them according to a

profit-sharing formula (an overage arrangement). No written contract existed but the parties had

agreed on many of the essential terms (though some important terms of the deal remained to be

agreed). Mr Cobbe believed that he and YRML were bound in honour though as an

experienced developer he knew that there was no legal commitment until contracts had been

exchanged. Mr Cobbe spent time and money on the effort to obtain the planning permission and

was successful. YRML then refused to conclude a formal agreement on the basis of the earlier

negotiations. YRML proposed a new deal that was more advantageous to it. Mr Cobbe refused

and brought proceedings based on proprietary estoppel and constructive trust, arguing that

17

[1987] HKLR 427 at 432 per Lord Templeman.

[1987] HKLR 427 at 435.

19

[2008] UKHL 55.

18

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

YRML was estopped from entering into a contract on the terms that had been agreed. He had

succeeded in the Court of Appeal but failed in the House of Lords. The House of Lords was not

prepared to accept Mr. Cobbes proprietary estoppel claim since there were important terms of

the contract still to be agreed and since the parties clearly envisaged that there would be a

formal written contract. The seminal authorities all show that the claimant must have an

expectation of a certain interest in land. Mr Cobbe did not satisfy this since he was fully aware

that there was no binding contract nor any other basis on which he could have claimed such an

interest.

Documents marked 'subject to contract' cannot form the basis of a proprietary estoppel claim:

'The reason why, in a "subject to contract" case, a proprietary estoppel cannot ordinarily

arise is that the would-be purchaser's expectation of acquiring an interest in the property

is subject to a contingency that is entirely under the control of the other party to the

negotiations ... The expectation is therefore speculative.'20

Subject to contract gives expression to the idea that the parties have no intention to be bound

but are still negotiating and are free to change their minds. The parties rights are only affected

when either the expected contract has been formed or the landowner gives a representation

which can reasonably be relied upon. Mere hope of an interest is not enough. There must be a

confident expectation that one has, or would acquire, an interest in the land. But both parties

here knew that the argument was not binding.

Although the proprietary estoppel claim failed, the House of Lords ordered YRML to make a

reasonable payment to Mr. Cobbe for his professional work and expenses in obtaining the

planning permission provided he allowed YRML to use the drawings produced for the purposes

of getting planning permission. Lord Scott thought that unjust enrichment, quantum meruit or the

doctrine of total failure of consideration could each be invoked to support this conclusion.

Sometimes it is clear that the parties intend to give binding assurances without entering into a

formal contract. In Herbert v Doyle21 H and D were neighbours who had negotiated an

20

21

Cobbe v Yeomans Row Management Ltd [2008] UK HL 55.

[2010] EWCA Civ 1095, CA (Eng).

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

agreement for the exchange of interests in land. They reached agreement on the terms at a

meeting in February 2003. In April 2003 they had a further meeting at which they agreed to

proceed on the basis of the February agreement. Both sides intended to be bound as a result of

the April meeting. In essence, the question was whether this agreement gave rise to a

constructive trust and was enforceable. For reasons that are peculiar to England and that do not

apply in Hong Kong the court spoke of constructive trust instead of proprietary estoppel but the

principles are essentially the same. The judge at first instance held that the agreement did give

rise to a constructive trust. On appeal, H argued that the first instance decision was

incompatible with the House of Lords decision in Cobbe v Yeoman's Row.

Arden LJ found that the agreement did give rise to an enforceable constructive trust. In an

important passage she said that an agreement will not give rise to a constructive trust (or to a

claim in proprietary estoppel) where: (1) a formal agreement is contemplated but not concluded;

(2) some of the terms to be agreed have not been agreed so that the interest in property is not

identified; or (3) the parties did not expect their agreement to be immediately binding.22 There

was some doubt as to whether the property that was the subject of the agreement had been

identified with sufficient certainty. In the end this doubt was resolved in D's favour. The court felt

able to fill in the gaps in the agreement in this regard; this was not a case of an incomplete

agreeement. Thus, none of the three factors were present here and the judge at first instance

had been right to find that there was a constructive trust.

The fact that a statement is made in the course of subject to contract negotiations, or where

there is a clear expectation that the parties will either be bound by a contract or not at all, then

there can normally be no proprietary estoppel claim. There are, however, exceptional

circumstances in which statements made in this context clearly were assurances that were

meant to be relied upon. In such cases, the door is open for a proprietary estoppel claim to

succeed. In Gonthier v Orange,23 the English Court of Appeal seems to have been open to the

possibility of a proprietary estoppel claim being based on assurances given in subject to

contract negotiations (for the grant of a lease and an option to purchase the reversion).

22

23

[2010] EWCA Civ 1095, CA (Eng) at [57].

[2003] EWCA Civ 873.

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

In Kinane v Alimamy Mackie-Conteh24 Arden LJ expressed the view that a proprietary estoppel

could arise in cases where there is an agreement that did not comply with the formalities to be

observed in the creation of a contract concerning land. In the ordinary case, the fact that the

parties have not yet satisfied the formalities or have used the subject to contract label is an

indication that they do not intend to be bound. But there can be other cases where the

promissor not only promises to create or transfer an interest in land but gives a double

assurance that he will not rely on the failure to comply with statutory formalities.25 Arden LJ

stressed that it is the landowners representation that the agreement is valid and binding that

gives rise to the estoppel.

In Pakwell Investment Ltd v CRC Department Store,26 Pakwell was negotiating for the grant to it

of a lease of a large amount of space used as a department store. The negotiations were

concluded and by mid-July 1999, the parties were preparing to exchange contracts. The final

agreement had been prepared. All the correspondence until that time had been 'subject to

contract' but on 13th and 14th July there was an exchange of correspondence (concerning the

arrangements for concluding the contract) that was not expressly made subject to contract.

There was a change in management at CRC and it decided not to proceed with the transaction.

Pakwell sought damages for breach of contract or relief based on proprietary estoppel. The

contract claim failed. The subject to contract label had not been removed expressly or by

necessary implication and it applied to the correspondence on 13th and 14th July. The judge

seems to have been open to the possibility that an assurance had been given for the purposes

of proprietary estoppel but said that even if there were an assurance CRC was not committed

unless there had been detrimental reliance.27 Pakwell had incurred expenditure linked to its

project and the taking of the lease but the judge found that this was expenditure that it would

probably have incurred anyway as it prepared for its hoped for and anticipated exchange of

contracts. There was no evidence of extra expenditure specifically in reliance on any assurance

that might have been given that the agreement would be concluded. The proprietary estoppel

claim also failed.

24

[2005] EWCA Civ 45, CA (Eng).

[2005] EWCA Civ 45, CA (Eng), para. 28 per Arden L.J.

26

[2002] HKEC 112.

27

[2002] HKEC 112 at [20].

25

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

The relief

The court has discretion when it comes to fashioning an appropriate remedy. Equity seeks to do

the minimum to prevent an unconscionable outcome. Thus, the court will not always completely

satisfy the expectation that has been created. Where the assurance is clear in terms of the

property that has been promised then the English position is that it will usually be appropriate to

give effect to that assurance if the necessary element of detrimental reliance is present.28

Proprietary estoppel and part performance

There are similarities between the facts that might give rise to a part performance claim and to a

claim in proprietary estoppel. A would-be purchaser might rely on either ground to try to enforce

the promise to transfer (or create) an interest in land. The acts of part performance might also

count as the detrimental reliance needed for proprietary estoppel. Clearly, proprietary estoppel

is wider in scope since it can operate outside the contractual context. Even in the contractual

setting, part performance makes the contract enforceable while a proprietary estoppel claim

leaves the court with a wide discretion as to the remedy to be awarded; the court might not

simply give effect to the representation made.

The rule in Walsh v Lonsdale

The equitable maxim that equity looks on as done that which ought to be done gives rise to the

rule in Walsh v Lonsdale. This rule presupposes that there is an enforceable agreement for a

lease or the sale of a lease (or of some other interest in land). That is to say it comes into play

when there is a valid contract that complies with the requirements of section 3(1) of the

Conveyancing and Property Ordinance or made enforceable by an act of part performance.

Under the rule in Walsh v Lonsdale, equity treats the agreement as being as good as a formal

lease or transfer. Even if the parties have, for some reason, not gone the further step and

entered into a deed, equity will regard the transaction as having taken effect even though the

common law does not.

There must be an agreement in respect of which specific performance is available. Specific

performance is generally available for breach of a contract for the sale or other disposition of

28

Suggitt v Suggitt [2012] EWCA Civ 1140, CA (Eng).

10

Hong Kong Land Law

Michael Lower

Contracts II

land. The remedy of specific performance must not have been excluded.29 The usual equitable

principles apply so, for example, the plaintiff must come with clean hands. The interest of the

tenant (or buyer) arising out of the rule in Walsh v Lonsdale is equitable. The distinction

between legal and equitable interests is significant in some contexts, in particular in questions

concerning the priority of interests.

The seller as constructive trustee

Once a valid and enforceable contract is in place, the seller holds the property as constructive

trustee for the buyer and risk passes to the buyer.30 The seller owes the buyer a duty of care to

look after the property.31 The fiduciary relationship is qualified in a number of respects. First, the

seller is entitled to remain in possession and in receipt of the profits until formal completion.32

Further, the seller has a lien over the property until the full purchase price has been paid.33 The

buyer, too, has a lien over the property as security for the part of the purchase price that has

been paid.34 Moreover, the seller is entitled to give priority to the protection of his own interest in

the property.35

29

Wong Lai Fan v Lee Ha [1992] HKLR 125.

Lysaght v Edwards (1876) 2 Ch D 499.

31

Clarke v Ramuz [1891] 2 QB 456.

32

Gedye v Montrose (1858) 26 Beav 45; Cuddon v Tite (1858) 1 Giff. 495.

33

Re Birmingham, Savage v Stannard [1959] Ch. 523.

34

Li Sze Fat v Cheng Ka Leung Tommy [2000] 3 HKC 432. See Wong Kam Fung v Smart Profit

Enterprises Ltd [2014] 5 HKLRD 853, CA for a recent consideration of this.

35

Shaw v Foster (1872) LR 5 HL 321.

30

11

Вам также может понравиться

- PppeДокумент2 страницыPppepppОценок пока нет

- BP0153371 Land LawДокумент8 страницBP0153371 Land LawChand LughmaniОценок пока нет

- Cengage Advantage Books Law For Business 18th Edition Ashcroft Solutions ManualДокумент6 страницCengage Advantage Books Law For Business 18th Edition Ashcroft Solutions Manualdylansophie4cz7ey100% (21)

- Property Law - KARISHMAДокумент8 страницProperty Law - KARISHMAkkkОценок пока нет

- Parol Evidence Rule and Its ExceptionsДокумент3 страницыParol Evidence Rule and Its ExceptionsRyan RamkirathОценок пока нет

- Short Assignment 4 (Legal Status of Bitcoins in India)Документ10 страницShort Assignment 4 (Legal Status of Bitcoins in India)Varsha ThampiОценок пока нет

- And The Statute of Frauds: Indebitatus AssumpsitДокумент19 страницAnd The Statute of Frauds: Indebitatus AssumpsitEmailОценок пока нет

- Discharge JoooДокумент4 страницыDischarge Jooopaco kazunguОценок пока нет

- Part Performance Readings - Part BДокумент12 страницPart Performance Readings - Part Bbeffereyjezos420Оценок пока нет

- Parole Evidence and Malaysian CasesДокумент22 страницыParole Evidence and Malaysian CasesAisyah MohazizОценок пока нет

- BP0153338 Land Law Semester I3Документ5 страницBP0153338 Land Law Semester I3Chand LughmaniОценок пока нет

- Assignment - Commercial LawДокумент15 страницAssignment - Commercial LawNURKHAIRUNNISAОценок пока нет

- Lease & Tenancies (NLC)Документ30 страницLease & Tenancies (NLC)NotWho Youthink Iam0% (1)

- Lizzy's AssignmentДокумент7 страницLizzy's AssignmentOlu FemiОценок пока нет

- Home Stake Production Company, A Corporation v. Trustees of Iowa College, Grinnell, Iowa, A Corporation, 331 F.2d 919, 10th Cir. (1964)Документ4 страницыHome Stake Production Company, A Corporation v. Trustees of Iowa College, Grinnell, Iowa, A Corporation, 331 F.2d 919, 10th Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Contract Law Lecture 3 - Discharge and Remedies PowerPointДокумент55 страницContract Law Lecture 3 - Discharge and Remedies PowerPointTosin YusufОценок пока нет

- S206 (3) National Land CodeДокумент25 страницS206 (3) National Land CodeCarmel Grace PhilipОценок пока нет

- Section 2 of The 2019 Contracts Act Currie V Misa Case Basic Principles of English Contract Law Balfour V Balfour (1919) 2 KB 571Документ6 страницSection 2 of The 2019 Contracts Act Currie V Misa Case Basic Principles of English Contract Law Balfour V Balfour (1919) 2 KB 571William manzhi KajjubiОценок пока нет

- Law of Contract: FrustrationДокумент12 страницLaw of Contract: FrustrationJ. Angel AiozОценок пока нет

- Law of Conveyancing PDFДокумент25 страницLaw of Conveyancing PDFFreya MehmeenОценок пока нет

- Coursework Assigment 1Документ4 страницыCoursework Assigment 1Vittu7kОценок пока нет

- Contract 14: Study Online atДокумент5 страницContract 14: Study Online atnhsajibОценок пока нет

- Law of Contract AssignmentДокумент5 страницLaw of Contract AssignmentOlu FemiОценок пока нет

- Unenforceable ContractsДокумент22 страницыUnenforceable ContractsSweet Zel Grace Porras100% (1)

- Contract Law 2 Class Notes.Документ6 страницContract Law 2 Class Notes.GEOFFREY KAMBUNIОценок пока нет

- Contract Law Sem 2Документ30 страницContract Law Sem 2NAMATOVU JOVIAОценок пока нет

- Module 13 Obligations and ContractsДокумент9 страницModule 13 Obligations and ContractsShayne PagwaganОценок пока нет

- Land Contracts 2023Документ8 страницLand Contracts 20237j74xxqpbtОценок пока нет

- Lavanya Contract 1 Assignment With FootnotingДокумент15 страницLavanya Contract 1 Assignment With FootnotingLAVANYA SОценок пока нет

- What Is Innocent Misrepresentation in Real Estate?Документ7 страницWhat Is Innocent Misrepresentation in Real Estate?Farzana Mahamud RiniОценок пока нет

- Foundation in Business Introduction To Law: Submission Due Date & Time:2 September 2022Документ11 страницFoundation in Business Introduction To Law: Submission Due Date & Time:2 September 2022pavi ARMYОценок пока нет

- 50 Marta C Ortega Vs Daniel Leonardo103 Phil 870Документ3 страницы50 Marta C Ortega Vs Daniel Leonardo103 Phil 870Nunugom SonОценок пока нет

- G Percy Trentham LTD V Archital Luxfer LTD 1992Документ5 страницG Percy Trentham LTD V Archital Luxfer LTD 1992Longku dieudonneОценок пока нет

- Mistake 1Документ10 страницMistake 1niyiОценок пока нет

- Lepatan, Reynaldo Jr. F - Oblicon Case Study Arts 1356-1379Документ16 страницLepatan, Reynaldo Jr. F - Oblicon Case Study Arts 1356-1379Reynaldo Lepatan Jr.Оценок пока нет

- LeasesДокумент12 страницLeasesAmal wickramathungaОценок пока нет

- BSM 743 2015 - Lecture Notes 4Документ21 страницаBSM 743 2015 - Lecture Notes 4Mace StudyОценок пока нет

- A. The Actions of R2Detour Falls Under The Contours of MisrepresentationДокумент11 страницA. The Actions of R2Detour Falls Under The Contours of MisrepresentationHebah InnahОценок пока нет

- Limketkai Sons MillingДокумент77 страницLimketkai Sons MillingKazumi ShioriОценок пока нет

- 36-01 Clarin vs. RulonaДокумент1 страница36-01 Clarin vs. RulonaBernz Velo TumaruОценок пока нет

- SLL Contract Assignment Grp. 2Документ29 страницSLL Contract Assignment Grp. 2Jacob komba EllieОценок пока нет

- Lease License DistinctionДокумент6 страницLease License Distinctionminha aliОценок пока нет

- Dosya - 13634 - Intention To Create Legal RelationsДокумент10 страницDosya - 13634 - Intention To Create Legal RelationsDave NОценок пока нет

- Exception To The Doctrine of PrivityДокумент60 страницException To The Doctrine of PrivityALOK RAOОценок пока нет

- Ome Written Memorandum or Note of The Agreement Signed by The Party To Be Charged Under The Agreement or His Authorised AgentДокумент13 страницOme Written Memorandum or Note of The Agreement Signed by The Party To Be Charged Under The Agreement or His Authorised AgentJoyce HuОценок пока нет

- Centredale Investment Company v. Prudential Insurance Company of America, 540 F.2d 16, 1st Cir. (1976)Документ7 страницCentredale Investment Company v. Prudential Insurance Company of America, 540 F.2d 16, 1st Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Transfer of Property ActДокумент20 страницTransfer of Property ActManbaniKaurOhriОценок пока нет

- Time As An Essence of ContractДокумент13 страницTime As An Essence of ContracttapeshraghavОценок пока нет

- Freehold Covenants (2020)Документ13 страницFreehold Covenants (2020)mickayla jonesОценок пока нет

- Running Head: AssignmentДокумент11 страницRunning Head: Assignmentmanahil siddiquiОценок пока нет

- Doctrine of Frustration-2022b WeeknedДокумент6 страницDoctrine of Frustration-2022b Weeknedakwasiamoh501Оценок пока нет

- MACALINOДокумент11 страницMACALINOChelsea MacalinoОценок пока нет

- Doctrine of Part Performance Part - 1Документ27 страницDoctrine of Part Performance Part - 1Ankit SahniОценок пока нет

- Property Law: Doctrine of Part Performance Assignment Semester 3Документ13 страницProperty Law: Doctrine of Part Performance Assignment Semester 3AnonymousОценок пока нет

- Tpa-Doctrine of Part PerformanceДокумент16 страницTpa-Doctrine of Part PerformanceAnshu Raj Singh100% (6)

- Conveyancing Chapter 1 Part 1Документ15 страницConveyancing Chapter 1 Part 1Crystal Blossoms100% (2)

- Business LawДокумент10 страницBusiness LawKeshvin SidhuОценок пока нет

- Law School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesОт EverandLaw School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesОценок пока нет

- Cape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyОт EverandCape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyОценок пока нет

- Liberty NotesДокумент8 страницLiberty NotespppОценок пока нет

- Chum Mei Diu V Sum Fan Hung: Citations: Presiding Judges: PhrasesДокумент21 страницаChum Mei Diu V Sum Fan Hung: Citations: Presiding Judges: PhrasespppОценок пока нет

- Pakwell Investment LTD V CRC Department Store LTD: Citations: Judge Name: PhrasesДокумент11 страницPakwell Investment LTD V CRC Department Store LTD: Citations: Judge Name: PhrasespppОценок пока нет

- Part Performance, The Constructive Trust and Proprietary EstoppelДокумент1 страницаPart Performance, The Constructive Trust and Proprietary EstoppelpppОценок пока нет

- Proprietary Estoppel, Constructive Trust and Co - Habiting CouplesДокумент1 страницаProprietary Estoppel, Constructive Trust and Co - Habiting CouplespppОценок пока нет

- Business Law (Part 2) - Semester 1 - Part Time MBA AssignmentДокумент11 страницBusiness Law (Part 2) - Semester 1 - Part Time MBA AssignmentanishgowdaОценок пока нет

- Unit 1 Indian Contract Act 1872Документ48 страницUnit 1 Indian Contract Act 1872DeborahОценок пока нет

- BBOXX Solar Franchise AgreementДокумент12 страницBBOXX Solar Franchise Agreementbugti1986Оценок пока нет

- Assignment April 7 2021Документ5 страницAssignment April 7 2021esmeralda de guzmanОценок пока нет

- Contract Lessons Sem 1Документ16 страницContract Lessons Sem 1Elena JuvinaОценок пока нет

- Torts Mid Terms ReviewerДокумент8 страницTorts Mid Terms ReviewerApple Licuanan100% (1)

- Satisfying The Minimum Equity Equitable Estoppel Remedies After Verwayen PDFДокумент44 страницыSatisfying The Minimum Equity Equitable Estoppel Remedies After Verwayen PDFwОценок пока нет

- CONTRACT FOR PRACTICUM (Canteen)Документ6 страницCONTRACT FOR PRACTICUM (Canteen)Mark Anthony Nieva RafalloОценок пока нет

- Obligations and Contracts Reviewer AteneoДокумент27 страницObligations and Contracts Reviewer AteneoPhoebe PuaОценок пока нет

- Law of ContractДокумент48 страницLaw of ContractHairulanuar SuliОценок пока нет

- (1979) - 1-W L R - 401Документ8 страниц(1979) - 1-W L R - 401Anonymous yr4a85Оценок пока нет

- Privity of ContractДокумент15 страницPrivity of ContractAyishah HafizahОценок пока нет

- Sid Sudiacal - Reflection On SalvationДокумент8 страницSid Sudiacal - Reflection On Salvationcoolaquarius1688Оценок пока нет

- Contract 1 QPДокумент22 страницыContract 1 QPAnirudh JadhavОценок пока нет

- 11 NegligenceДокумент11 страниц11 Negligencenatsu lolОценок пока нет

- Negligence: Proof of Breach & Causation: Civil Liability Act S 5D: TWO STAGE INQUIRYДокумент6 страницNegligence: Proof of Breach & Causation: Civil Liability Act S 5D: TWO STAGE INQUIRYjatgbeОценок пока нет

- Proximate Cause and Scope of Liability Chapters 11 & 12 - Geistfeld - Product LiabilityДокумент93 страницыProximate Cause and Scope of Liability Chapters 11 & 12 - Geistfeld - Product LiabilityGeorge ConkОценок пока нет

- Contributory NegligenceДокумент2 страницыContributory NegligencefinalfrontlineОценок пока нет

- ACCA F4 Contract LawДокумент7 страницACCA F4 Contract LawAbdulHameedAdamОценок пока нет

- Consideration: Contract LawДокумент15 страницConsideration: Contract LawNandini TarwayОценок пока нет

- CLFДокумент8 страницCLFMithila PatelОценок пока нет

- Discharge of ContractДокумент6 страницDischarge of Contractammie syazlyneОценок пока нет

- Law of Contract (Lec 2)Документ44 страницыLaw of Contract (Lec 2)RaymondMillsОценок пока нет

- Obligations and Contracts Jurado Reviewer PDFДокумент70 страницObligations and Contracts Jurado Reviewer PDFRaymond Ruther87% (15)

- Respondent Moot Problem 1Документ21 страницаRespondent Moot Problem 1Mukesh Singh100% (1)

- Essential Elements of ContractДокумент48 страницEssential Elements of ContractGeetanjali AlisettyОценок пока нет

- Cali Lesson NotesДокумент22 страницыCali Lesson NotesjamcarthОценок пока нет

- The Millennium and The End of SinДокумент1 страницаThe Millennium and The End of SinEd PayetОценок пока нет

- 1.0 Freedom of Contract in Sales of Goods Act 1957Документ9 страниц1.0 Freedom of Contract in Sales of Goods Act 1957Tip TaptwoОценок пока нет

- Acca f4 Law Spreadsheet - Sheet1Документ3 страницыAcca f4 Law Spreadsheet - Sheet1Corene Roxy Pro100% (1)