Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

How Lower Efficiency Can Reduce Overall Cost

Загружено:

KrrishАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

How Lower Efficiency Can Reduce Overall Cost

Загружено:

KrrishАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

How lower efficiency can reduce overall cost

OCTOBER 19, 2015

Share

by Joe Evans, Pump Ed 101

When we start the pump selection process for a particular application, one of our major concerns is efficiency.

If several different models of similar quality meet our conditions we will usually select the one with the highest

efficiency. After all, higher efficiency reduces the cost of electrical power. There are times, however, when

efficiency can take a back seat to the true, overall cost of operation.

Solids handling pumps used in municipal and industrial applications are a good example. Large sewage pumps

can use mixed flow or radial flow impellers with little concern of plugging or clogging due to the inherent

size of the flow passages. As discharge and vane size decrease, however, the potential for clogging increases.

In the early 1900s a new impeller design was developed by A.B. Wood of the New Orleans Sewage and Water

board. Known as the non-clog impeller, it consisted of two vanes with blunt leading edges that allowed the

passage of larger solids and reduced the opportunity for stringy material to accumulate at the vane entry.

Today, most solids handling pumps, with discharges smaller than 10, utilise some variation of this design.

Those of us familiar with these pumps know that there is no such thing as a non-clog pump seldom clog is

probably a better terminology. But, as discharge size decreases to 4 or smaller, often clog can become the

description of choice.

Now, some 3 and 4 pumps can pass a full 3 spherical solid, but some applications cannot accommodate

the higher flows they produce and high concentrations of stringy material can still cause problems. If a small

non-clog performs well in an application it is probably the best choice but, if plugging is a continual problem,

you may want to consider an alternative.

The vortex pump, also known as a recessed impeller pump, is usually considered to be a member of the

centrifugal family. This is not entirely accurate, but since there is no such thing as centrifugal force, it probably

doesnt matter anyway. It is, however, a dynamic pump as it imparts energy continuously to the fluid it is

pumping.

Unlike the typical centrifugal pump, its pumping action is a two stage process. The impeller, which is located

outside the flow area of the volute, produces a primary vortex or swirling action in the water that resides in

and around its vanes. This vortex creates a secondary vortex in the volute that produces flow. Figure 1

illustrates this process.

Figure 1.

The pumping action of the vortex pump offers several significant advantages. Since the impeller is recessed,

it has little contact with the majority of the pumpage. Even when solids do contact the impeller, they do not

have to traverse the vanes so the potential for erosion is greatly reduced. In addition to reduced wear, its

recessed position also allows the passage of larger solids and stringy materials that might otherwise plug a

true centrifugal pump. Almost any solid that can enter the suction will exit the volute and stringy materials

pass through without entanglement. Still another advantage is a reduction in the radial forces that act upon its

impeller. Because of this reduction, many vortex pumps can operate at very low flows or even shut off for

extended periods without damage.

Unfortunately, that two-step pumping process also has a disadvantage a much lower hydraulic efficiency.

This trade off tends to be acceptable in many industrial markets but, unfortunately, it will often eliminate the

vortex pump from consideration by some specifying engineers in the municipal arena.

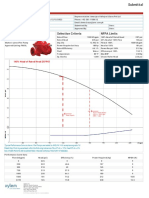

Figure 2 compares a 4 vortex pump with a 4 non-clog. Both are rated to pass 3 spherical solids and reach

their peak efficiency at the design point (450 gpm @ 46). At this point the non-clog requires about 7.4

horsepower (efficiency = 70 per cent) while the vortex pump requires about 10.7 horsepower (efficiency = 48

per cent). Obviously, this almost 45 per cent increase in horsepower could have a rather large impact on long

term electrical costs, but will this increase always make the non-clog the better choice? Lets take a look at a

actual municipal example.

A small municipality in the western US installed a duplex lift station, with alternating 4 non-clogs, to service

a retail complex. The complex consists of retail shops, a supermarket/department store, and several

restaurants. The station has an average of six to seven starts per day and the run time for each cycle is

approximately five minutes. In addition to normal human and food wastes, disposable diapers, feminine

products, and high fibre paper towels are also a daily occurrence. This waste mix resulted in partially plugged

pumps that had to be pulled for cleaning every seven to ten days. Late last summer, the non-clogs were

replaced with 4 vortex pumps that produced similar head capacity characteristics. Since start up of the new

pumps, no plugging has occurred.

Figure 2.

Although the vortex pumps consume approximately 38 per cent more horsepower than the non-clogs they

replaced, the total power consumed is still relatively small since the pumps run no more than 35 minutes per

day (213 hours per year). On the other hand, cleaning of the original non-clogs (over and above normal

maintenance) required an average of 12 hours per month (144 hours per year). The replacement resulted in

labor cost savings that far outweighed the additional electrical cost and, most importantly, made the pump

station completely reliable.

There are times when we have to look beyond efficiency and its effect on electrical consumption, especially

if operational hours are low. In the example above, and many more like it, overall cost and reliability can be

far more important considerations.

Joe Evans accidentally entered the pump industry in 1986, and has been trapped there ever since! He is

passionate about the sharing of knowledge within the industry. To read more of his insights into the world of

pumping, head to www.pumped101.com.

Source: Link

Вам также может понравиться

- Hydraulic Ram Pump Research Programme Technical ReleaseДокумент6 страницHydraulic Ram Pump Research Programme Technical ReleaseAirPop24Оценок пока нет

- How to Select the Right Centrifugal Pump: A Brief Survey of Centrifugal Pump Selection Best PracticesОт EverandHow to Select the Right Centrifugal Pump: A Brief Survey of Centrifugal Pump Selection Best PracticesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Hydram PDFДокумент6 страницHydram PDFDedi SatriyawanОценок пока нет

- Sewer Bypass PumpingДокумент6 страницSewer Bypass PumpingSohaib AhmedОценок пока нет

- Selection of Artificial Lift MethodДокумент5 страницSelection of Artificial Lift MethodAngel David Ponce OropezaОценок пока нет

- WWJArticle20 VTP Part1May03Документ5 страницWWJArticle20 VTP Part1May03Tarık DikbasanОценок пока нет

- Design and installation of a reciprocating water pumpДокумент22 страницыDesign and installation of a reciprocating water pumpAshokОценок пока нет

- Dewatering Bore Pumps - Reducing Costs and Emissions by Maximising Pumping Efficiency Over TimeДокумент4 страницыDewatering Bore Pumps - Reducing Costs and Emissions by Maximising Pumping Efficiency Over TimeMaiza HussinОценок пока нет

- Chapter Five Jet Pumping System (JP)Документ33 страницыChapter Five Jet Pumping System (JP)mghareebОценок пока нет

- Wear Rings: Contributed by Zoeller Engineering DepartmentДокумент2 страницыWear Rings: Contributed by Zoeller Engineering DepartmentAjay VishwakarmaОценок пока нет

- Pumps Turbine Submersible PumpДокумент11 страницPumps Turbine Submersible Pumpahsanul haqueОценок пока нет

- Pump Selection HandbookДокумент12 страницPump Selection Handbookpapathsheila100% (1)

- Quick A Easy Guide: To Hydraulic Pump Technology and SelectionДокумент3 страницыQuick A Easy Guide: To Hydraulic Pump Technology and SelectionGustavОценок пока нет

- Submersible Pump - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент3 страницыSubmersible Pump - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediafloredaОценок пока нет

- Research Paper On PumpsДокумент4 страницыResearch Paper On Pumpsnikuvivakuv3100% (1)

- Pump FAQ's by Hydraulic Institute (UK)Документ61 страницаPump FAQ's by Hydraulic Institute (UK)Sajjad Ahmed100% (2)

- VAcuum Systems ComparisionДокумент8 страницVAcuum Systems ComparisionSANTOSHОценок пока нет

- Solar Water PumpingДокумент9 страницSolar Water PumpingsivaramanpsrОценок пока нет

- Vacuum AuditsДокумент8 страницVacuum AuditsBapu612345Оценок пока нет

- Using Pumps As Power Recovery TurbinesДокумент4 страницыUsing Pumps As Power Recovery TurbinesKali CharanОценок пока нет

- Experimental Fluid Mechanics: A Report OnДокумент9 страницExperimental Fluid Mechanics: A Report OnGanesh V IyerОценок пока нет

- NPTI, 3rd Year, 03915303712: Shivam TiwariДокумент6 страницNPTI, 3rd Year, 03915303712: Shivam TiwariMantuomОценок пока нет

- NPTI, 3rd Year, 03915303712: Shivam TiwariДокумент6 страницNPTI, 3rd Year, 03915303712: Shivam Tiwarishashi kant kumarОценок пока нет

- Centrifugal PumpДокумент13 страницCentrifugal Pumpafr5364Оценок пока нет

- Designing An Optimized Model of Water Lifting Device Without Conventional PracticesДокумент8 страницDesigning An Optimized Model of Water Lifting Device Without Conventional PracticesKishore RaviОценок пока нет

- Design Concepts For Power-Limiting Open-Circuit ArchitecturesДокумент22 страницыDesign Concepts For Power-Limiting Open-Circuit ArchitecturesCarlos Alberto Tizka ToledoОценок пока нет

- Pedal Operated Water Pump Literature ReviewДокумент7 страницPedal Operated Water Pump Literature Revieweaibyfvkg100% (1)

- Pump Basics. A Guide To Installation and SelectionДокумент18 страницPump Basics. A Guide To Installation and SelectionArsalan QadirОценок пока нет

- Pumps Selection 0703 HandbookДокумент12 страницPumps Selection 0703 Handbookkooljam83% (6)

- 6 Prime Movers of Energy: 6.1. PUMPSДокумент40 страниц6 Prime Movers of Energy: 6.1. PUMPSRodrigo DíazОценок пока нет

- Impeller Trim For PumpДокумент9 страницImpeller Trim For PumpkasiОценок пока нет

- Pumped Storage Speaker 9655 Session 664 1Документ12 страницPumped Storage Speaker 9655 Session 664 1Energy ParksОценок пока нет

- Variable Volume ReservoirДокумент3 страницыVariable Volume ReservoirVelibor KaranovicОценок пока нет

- Sump Pump Selection Final ReportДокумент19 страницSump Pump Selection Final ReportEngr Saad Bin SarfrazОценок пока нет

- Water Turbines: TurbineДокумент22 страницыWater Turbines: TurbineEr Eklovya SainiОценок пока нет

- SPE 89600 New Technologies Allow Small Coiled Tubing To Complete The Work Formerly Reserved For Large Coiled Tubing UnitsДокумент7 страницSPE 89600 New Technologies Allow Small Coiled Tubing To Complete The Work Formerly Reserved For Large Coiled Tubing UnitsmsmsoftОценок пока нет

- Studies On Inclined Water Wheel Spiral Pump Project Reference No.: 38S1382Документ5 страницStudies On Inclined Water Wheel Spiral Pump Project Reference No.: 38S1382JAERC IQQOОценок пока нет

- Sewer Bypass Fundamentals: Submersible Pumps vs Self-Priming Centrifugal PumpsДокумент4 страницыSewer Bypass Fundamentals: Submersible Pumps vs Self-Priming Centrifugal PumpsHung Leung Sang Eddy0% (1)

- 6 Prime Movers of Energy: 6.1. PUMPSДокумент40 страниц6 Prime Movers of Energy: 6.1. PUMPSIan AsОценок пока нет

- Rotary Positive Displacement PumpsДокумент16 страницRotary Positive Displacement Pumpsalexmuchmure2158Оценок пока нет

- Axial Flow Pumps Technical BulletinДокумент3 страницыAxial Flow Pumps Technical BulletinahadОценок пока нет

- ImpellersДокумент8 страницImpellersmoh_zaghloul5Оценок пока нет

- Conceptos Del BarrilДокумент5 страницConceptos Del BarrilJason ChupicaОценок пока нет

- Centrifugal Pump TutorialДокумент50 страницCentrifugal Pump TutorialZoempek CavaleraОценок пока нет

- Power Calculations For Pelton TurbinesДокумент19 страницPower Calculations For Pelton TurbinestamailhamОценок пока нет

- Pendulum Water PumpДокумент3 страницыPendulum Water PumpMectrosoft Creative technologyОценок пока нет

- 5 Key Things Power Plant Engineers Need to Know About PumpsДокумент8 страниц5 Key Things Power Plant Engineers Need to Know About Pumpskannagi198Оценок пока нет

- Pump Operating RangeДокумент2 страницыPump Operating RangeNikesh100% (1)

- Hydraulic Ram Research PapersДокумент8 страницHydraulic Ram Research Papersgvytgh3b100% (1)

- Low Pressure SewersДокумент23 страницыLow Pressure SewersUlil A JaОценок пока нет

- Rotary Pumps Tushaco CatalogueДокумент5 страницRotary Pumps Tushaco Catalogueenuvos engineeringОценок пока нет

- HOW To Design A Pump SystemДокумент9 страницHOW To Design A Pump SystemPierre NorrisОценок пока нет

- Centrifugal pump characteristicsДокумент23 страницыCentrifugal pump characteristicsmubara marafaОценок пока нет

- Operator’S Guide to Centrifugal Pumps: What Every Reliability-Minded Operator Needs to KnowОт EverandOperator’S Guide to Centrifugal Pumps: What Every Reliability-Minded Operator Needs to KnowРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- Hydraulics and Pneumatics: A Technician's and Engineer's GuideОт EverandHydraulics and Pneumatics: A Technician's and Engineer's GuideРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (8)

- Pneumatic and Hydrautic Conveying of Both Fly Ash and Bottom AshОт EverandPneumatic and Hydrautic Conveying of Both Fly Ash and Bottom AshОценок пока нет

- CCM1 - Sump Pump 1Документ4 страницыCCM1 - Sump Pump 1KrrishОценок пока нет

- SL1808075451DCДокумент10 страницSL1808075451DCKrrishОценок пока нет

- ECHm4-60-F 2024-03-05 220645 017Документ6 страницECHm4-60-F 2024-03-05 220645 017KrrishОценок пока нет

- CCM1 - Sump Pump 1Документ4 страницыCCM1 - Sump Pump 1KrrishОценок пока нет

- Hydro Mpce 2 Crie203Документ6 страницHydro Mpce 2 Crie203KrrishОценок пока нет

- AC Fire SelectorДокумент1 страницаAC Fire SelectorKrrishОценок пока нет

- CCM1 - Sump Pump 1Документ4 страницыCCM1 - Sump Pump 1KrrishОценок пока нет

- CCM1 - Sump Pump 1Документ4 страницыCCM1 - Sump Pump 1KrrishОценок пока нет

- CCM1 - Sump Pump 1Документ4 страницыCCM1 - Sump Pump 1KrrishОценок пока нет

- AC Fire SelectorДокумент1 страницаAC Fire SelectorKrrishОценок пока нет

- SV 055 iP5A 2 N O L (Class) : Model NumberДокумент1 страницаSV 055 iP5A 2 N O L (Class) : Model NumberAbdul RafaeОценок пока нет

- Hydro MPCE 2 CRE152 U2 AAGAДокумент6 страницHydro MPCE 2 CRE152 U2 AAGAKrrishОценок пока нет

- Grundfos Pump CRN2 CRN2G Parts D1101Документ6 страницGrundfos Pump CRN2 CRN2G Parts D1101KrrishОценок пока нет

- Addressing Dewatering Challenges With Intelligent Drive Solutions MiningДокумент2 страницыAddressing Dewatering Challenges With Intelligent Drive Solutions MiningKrrishОценок пока нет

- AC Fire SelectorДокумент1 страницаAC Fire SelectorKrrishОценок пока нет

- AC Fire SelectorДокумент1 страницаAC Fire SelectorKrrishОценок пока нет

- Technical Data: 10SV08N030TДокумент3 страницыTechnical Data: 10SV08N030TKrrishОценок пока нет

- AC Fire SelectorДокумент1 страницаAC Fire SelectorKrrishОценок пока нет

- Flygt A-C Series: WCXH Axial Flow PumpsДокумент4 страницыFlygt A-C Series: WCXH Axial Flow PumpsKrrishОценок пока нет

- Flygt A C Series Large Split Case BrochureДокумент4 страницыFlygt A C Series Large Split Case BrochureKrrishОценок пока нет

- Hydro Mpce 4 Crie 204Документ5 страницHydro Mpce 4 Crie 204KrrishОценок пока нет

- Hydro MPCE 2 CRE152 U2 AAGAДокумент6 страницHydro MPCE 2 CRE152 U2 AAGAKrrishОценок пока нет

- Technical Data: 10SV08N030TДокумент3 страницыTechnical Data: 10SV08N030TKrrishОценок пока нет

- Flygt A-C Series Dry Pit Pumps: Reliable and Efficient Fluid Handling SolutionsДокумент4 страницыFlygt A-C Series Dry Pit Pumps: Reliable and Efficient Fluid Handling SolutionsKrrishОценок пока нет

- TAX RATE CARD 2021-22 Income Tax Withholding Rates Sales Tax Withholding RatesДокумент14 страницTAX RATE CARD 2021-22 Income Tax Withholding Rates Sales Tax Withholding RatesTax Management ConsultingОценок пока нет

- Submersible pumps for municipal sewage and surface water applicationsДокумент4 страницыSubmersible pumps for municipal sewage and surface water applicationsAhmed RazaОценок пока нет

- Grundfos Distributed Pumping: Intelligent Water-Cooling SystemДокумент21 страницаGrundfos Distributed Pumping: Intelligent Water-Cooling SystemKrrishОценок пока нет

- DP DPKДокумент70 страницDP DPKKrrishОценок пока нет

- StandbyДокумент1 страницаStandbyKrrishОценок пока нет

- System Syzer TEH-175AДокумент8 страницSystem Syzer TEH-175AMario JoséОценок пока нет

- Academy Broadcasting Services Managerial MapДокумент1 страницаAcademy Broadcasting Services Managerial MapAnthony WinklesonОценок пока нет

- Entrepreneurship Style - MakerДокумент1 страницаEntrepreneurship Style - Makerhemanthreddy33% (3)

- Corruption in PakistanДокумент15 страницCorruption in PakistanklutzymeОценок пока нет

- Sop EcuДокумент11 страницSop Ecuahmed saeedОценок пока нет

- Code Description DSMCДокумент35 страницCode Description DSMCAnkit BansalОценок пока нет

- Module 5Документ10 страницModule 5kero keropiОценок пока нет

- 2CG ELTT2 KS TitanMagazine Anazelle-Shan PromoДокумент12 страниц2CG ELTT2 KS TitanMagazine Anazelle-Shan PromoJohn SmithОценок пока нет

- Law of TortsДокумент22 страницыLaw of TortsRadha KrishanОценок пока нет

- Make a Battery Level Indicator using LM339 ICДокумент13 страницMake a Battery Level Indicator using LM339 ICnelson100% (1)

- AWC SDPWS2015 Commentary PrintableДокумент52 страницыAWC SDPWS2015 Commentary PrintableTerry TriestОценок пока нет

- Chaman Lal Setia Exports Ltd fundamentals remain intactДокумент18 страницChaman Lal Setia Exports Ltd fundamentals remain intactbharat005Оценок пока нет

- Cib DC22692Документ16 страницCib DC22692Ashutosh SharmaОценок пока нет

- I. ICT (Information & Communication Technology: LESSON 1: Introduction To ICTДокумент2 страницыI. ICT (Information & Communication Technology: LESSON 1: Introduction To ICTEissa May VillanuevaОценок пока нет

- Pig PDFДокумент74 страницыPig PDFNasron NasirОценок пока нет

- Employee Central Payroll PDFДокумент4 страницыEmployee Central Payroll PDFMohamed ShanabОценок пока нет

- SAP ORC Opportunities PDFДокумент1 страницаSAP ORC Opportunities PDFdevil_3565Оценок пока нет

- A320 Normal ProceduresДокумент40 страницA320 Normal ProceduresRajesh KumarОценок пока нет

- Department of Labor: kwc25 (Rev-01-05)Документ24 страницыDepartment of Labor: kwc25 (Rev-01-05)USA_DepartmentOfLaborОценок пока нет

- For Mail Purpose Performa For Reg of SupplierДокумент4 страницыFor Mail Purpose Performa For Reg of SupplierAkshya ShreeОценок пока нет

- Bob Duffy's 27 Years in Database Sector and Expertise in SQL Server, SSAS, and Data Platform ConsultingДокумент26 страницBob Duffy's 27 Years in Database Sector and Expertise in SQL Server, SSAS, and Data Platform ConsultingbrusselarОценок пока нет

- Improvements To Increase The Efficiency of The Alphazero Algorithm: A Case Study in The Game 'Connect 4'Документ9 страницImprovements To Increase The Efficiency of The Alphazero Algorithm: A Case Study in The Game 'Connect 4'Lam Mai NgocОценок пока нет

- Week 3 SEED in Role ActivityДокумент2 страницыWeek 3 SEED in Role ActivityPrince DenhaagОценок пока нет

- WitepsolДокумент21 страницаWitepsolAnastasius HendrianОценок пока нет

- SyllabusДокумент4 страницыSyllabusapi-105955784Оценок пока нет

- Royalty-Free License AgreementДокумент4 страницыRoyalty-Free License AgreementListia TriasОценок пока нет

- Case Study - Soren ChemicalДокумент3 страницыCase Study - Soren ChemicalSallySakhvadzeОценок пока нет

- Com 0991Документ362 страницыCom 0991Facer DancerОценок пока нет

- Okuma Osp5000Документ2 страницыOkuma Osp5000Zoran VujadinovicОценок пока нет

- DrugДокумент2 страницыDrugSaleha YounusОценок пока нет

- Take Private Profit Out of Medicine: Bethune Calls for Socialized HealthcareДокумент5 страницTake Private Profit Out of Medicine: Bethune Calls for Socialized HealthcareDoroteo Jose Station100% (1)