Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Exploring The Business Case For Children's Telebehavioral Health

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Exploring The Business Case For Children's Telebehavioral Health

Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

BRIEF

March 2015

Exploring the Business Case for Childrens

Telebehavioral Health

Introduction

John Gale, M.S.

David Lambert, PhD

Maine Rural Health Research

Center

Muskie School of Public Service

University of Southern Maine

This document was prepared for the Technical

Assistance Network for Childrens Behavioral

Health under contract with the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services,

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, Contract

#HHSS280201300002C. However, these

contents do not necessarily represent the

policy of the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services, and you should not assume

endorsement by the Federal Government.

This policy brief explores the business case for childrens telebehavioral health

services. In the first section, we place childrens telebehavioral health within the

context and demands of todays rural healthcare system, where the majority of

childrens telebehavioral health services are delivered. We then describe three

examples of the use of telebehavioral health to serve children, adolescents, and

families in rural communities. We end by exploring the business case for

telebehavioral health including the issues and challenges of service delivery,

coordination, and financing. This policy brief is informed by a national study of

telemental health (serving children, adults, and older persons) in rural health

systems conducted by the authors and updated to reflect the latest information on

three case examples.2

Overview and Background

Twenty percent of all children have a behavioral illness and most go untreated. A

chronic shortage of childrens specialty behavioral health clinicians contributes

significantly to this gap, particularly in rural areas. Telehealth including the use of

two-way televideo technology to provide health services at a distance, remote

patient monitoring, mobile health, and other telecommunication technologies

offers great promise to address this gap. Despite the promise of telehealth, its use

lags behind expectations.1 This has less to do with the technology itself and more to

do with the practical challenges of reimbursement, practice management, workforce

issues, and the economics of operating a rural behavioral health practice.

Telebehavioral health is being increasingly used to serve children and adolescents.3 It

is being used both to provide direct services including individual and family therapy,

evaluation and assessment, and medication management; support primary care

physicians (PCPs) who are treating mental health disorders in children (e.g., assisting

in assessment and medication management); and increase access to expert mental

health clinicians for the treatment of disorders such as autism. The quality and

portability of equipment and technology have increased as the costs of this

technology have decreased. Children and families tend to be more satisfied with

telebehavioral health than clinicians, but the satisfaction of clinicians is increasing as

they become more accustomed to its use.3

The Technical Assistance Network for Childrens Behavioral Health

2 | Evidence-Informed Practice in Systems of Care: Misconceptions and Facts

Research on the effectiveness of childrens telebehavioral health has lagged behind research on it use for

adults.3 The relatively few randomized clinical trials on childrens telebehavioral health have found it to be

effective and the evidence base is growing as more studies are designed and funded. One study has

established that childrens telebehavioral health can be employed to make valid and reliable psychiatric

diagnoses.4 Other studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of using telebehavioral health to provide

psychotherapy to children with depression, provide comprehensive care to children with attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorders, and enhance parent-training skills for parents of children with behavioral

health disorders. 5,6,7

Although the clinical evidence for childrens telebehavioral health is strong, we know less about the business

case. It is important to understand the opportunities and challenges to growing and sustaining a childrens

telebehavioral health program. As with telebehavioral health more generally, improved, more affordable

technology is available to provide effective evidence-based services. However, significant challenges arise

from the chronically low supply of childrens specialty behavioral health clinicians (especially child and

adolescent psychiatrists), the need to coordinate support and care for children with behavioral health

problems, and insufficient reimbursement. A recent study has found that telebehavioral health may be most

sustainable when it is delivered within networked systems of care. 1 This suggests that childrens

telebehavioral health may do well and be cost-effective within systems of care.

Childrens Telebehavioral Health in the Healthcare System: Three from the Field

Eastern Montana Telemedicine Network

The Eastern Montana Telemedicine Network (EMTN) began in 1993 as a cooperative effort between Billings

Clinic and five rural healthcare facilities in eastern Montana to explore the use of interactive

videoconferencing to improve access to medical specialty and mental health services. EMTN now has 42

partners in 29 communities throughout eastern and central Montana, northern Wyoming, and western North

Dakota. The use of technology to ensure a continuum of behavioral health care throughout its service area

has been an important focus for EMTN. Services include: medication review, follow-up visits to monitor

patient progress, discharge planning, individual and family therapy, emergency consultation, patient care

conferences, and employee assistance programs. Services are provided to adults, children, and families.

To support its rural partners, EMTN has recruited a board-certified child psychiatrist to join its telemedicine

team. In beginning his work, the psychiatrist quickly realized that he could not do this alone and needed to

enhance the capacity of providers and staff at the partner organizations to serve children and families. In

addition to delivering behavioral health services (e.g., assessments, medication management and review,

individual and family therapy, and patient care conferences) to children using telehealth technology, he also

uses technology to hold monthly educational sessions for local providers in the partner communities. He

identifies a key topic of concern among local providers for each monthly meeting and provides a brief 15 to

20 presentation on the topic. The remainder of the 60 minute session allows the participants to discuss the

issues and ask questions. These educational sessions are well attended and, in his opinion, have helped to

enhance local capacity and leverage scarce behavioral health resources. These educational sessions as well

as other non-reimbursable use of the telehealth network are funded through the network fees paid by

participating partners.

Contact: Thelma McClosky Armstrong, Director, tmcclosky@emtn.org

Teleconnect Therapies, Avalon, California

Each participating Rural Health Clinic (RHC) enters into a contract with Teleconnect Therapies, which is a

private telebehavioral health provider, for a negotiated number of monthly behavioral and psychotherapy

visits from licensed clinical social workers and psychologists. The RHCs pay Teleconnect Therapies directly

for their negotiated number of monthly visits and are responsible for third party and patient billing and

collection. Telehealth services are reimbursed by third party payers that include Medi-Cal (Californias

Medicaid Program which covers the provision of telebehavioral health) and Medicare (which only allows RHCs

to serve as originating sites as telebehavioral health is not a covered RHC service). Since its start in 2009,

Teleconnect Therapies has gradually increased the number of RHCs it works with and is currently providing

3 | Evidence-Informed Practice in Systems of Care: Misconceptions and Facts

services to patients in four RHCs in southern and mid-California using telehealth technology. Given the

differing organizational structures and cultures across the four RHCs, Teleconnect Therapies tailors its

working relationship to the unique needs, culture, and staffing issues of each practice through the use of a

Professional Services Agreement between the RHC and Teleconnect Therapies as the vendor. Issues addressed

in the Professional Services Agreement include: the number of contracted patient visits; rates for individual

and group visits; length of appointments; consultation space and other room requirements; responsibility for

providing and maintaining equipment and connections; staff credentialing; patient eligibility criteria; clinic

contact person; insurance preauthorization requirements; orientation to system; advertising services in the

rural community; referral and scheduling procedures; procedures for involuntary psychiatric holds or patient

medical emergencies during appointments; medical records and assessment forms, reports and

documentation; patient reminder calls; patient education materials; referrals to outside community

resources; procedures for discharging patients from the service; and provider time off.

Teleconnect Therapies also shares a portion of the financial risk related to the relatively high number of noshows (i.e., patients who do not appear for or cancel scheduled appointments) experienced by the RHCs.

While not unique to telehealth, no-shows create a significant financial burden for providers due to loss of

provider productivity. Besides sharing the financial risk of no-shows, Teleconnect has partnered with the

RHCs to reduce the no-show rate by implementing a patient reminder system that contacts patients twice in

the week before their scheduled appointments.

To supplement its direct care psychotherapy services, Teleconnect Therapies provides education and training

on behavioral health issues to staff at the RHC originating sites. Typically, the training is provided in the time

before a block of scheduled appointments are to occur. During the development of the service, Teleconnect

Therapies staff conduct site visits to the community to meet with RHC staff as well as key stakeholders and

behavioral health professionals at the local schools and service agencies. Teleconnect Therapies staff also

visit the RHC twice per year after the service is operational. These community site visits serve to develop a

relationship between the staff of the RHCs and Teleconnect Therapies and promote coordination between

the psychotherapy service and important community behavioral health supports. These services are provided

under the negotiated fees paid by the RHCs to Teleconnect Therapies and are intended to support the

success of the service at the RHC-level.

Teleconnect recommends developing a measured and planned implementation strategy. This has allowed the

fit between Teleconnect Therapies and the RHCs to be firmly established and provided time to address

implementation issues as they arise. It also allowed for the development of necessary relationships with local

referral and support services.

Contact: Dawn Simpson, Director, dsampson@teleconnecttherapies.com

University of Virginia, Office of Telemedicine, Charlottesville, Virginia

Operated by the University of Virginias (UVA) Office of Telemedicine, this telebehavioral health program

serves clients of all ages across Virginia. Children and adolescents are the largest group served and account

for the majority of telebehavioral health encounters. The program originally served rural underserved areas

of Appalachia, but has since expanded throughout the state. Although the program now receives requests for

services from urban areas, it primarily serves rural communities. Medicaid is the largest payer for

telebehavioral health services. Regional community service boards (CSBs), organizations that coordinate the

delivery of mental health services to public and some limited private clients, contract with UVA to purchase

negotiated blocks of time (typically 40-60 hours a week). The CSBs can use these hours as needed to address

the needs of their clients. The CSBs absorb the financial risk of no-shows and uninsured patients and are

responsible for billing Medicaid and other payers.

UVAs psychiatry residency program provides the foundation for the telebehavioral health service as senior

psychiatry residents provide much of the direct care services, primarily evaluation and medication

management, with supervision provided by the clinical faculty. Improved portability and functionality of

televideo equipment have increased the number of originating sites that may be served. Over time, the

program has evolved to better serve the needs of children and adolescents through expansion of services,

additions to the treatment team, and enhanced capacity of the behavioral health workforce. The programs

4 | Evidence-Informed Practice in Systems of Care: Misconceptions and Facts

initial focus on evaluation and assessment has broadened to include ongoing management of care including

psychotherapy and medication management. The services of the psychiatric residents have been

supplemented by the use of psychiatric nurse practitioners and licensed mental health counselors. UVA has

also provided training to rural behavioral health providers throughout the state using telebehavioral health

technology to enhance their skills and improve local system capacity. These trainings are provided as part of

the fee structure paid by the CSBs and the residency training program.

Contact: David C. Gordon, Director, dcc2j@virginia.edu

The Business Case for Telebehavioral Health within Childrens System of Care

Technology is not the limiting factor to expanded use of telebehavioral health to serve rural and other

underserved areas. Costs of equipment and operation have dropped while the quality of the transmissions has

increased. This allows expanded use in a variety of settings. Given their familiarity with technology, children

and adolescents tend to be very comfortable receiving telebehavioral health services. The primary challenge

involves how to best use telebehavioral health to provide direct care services and enhance provider capacity

within a regional childrens system of care. Other challenges include management of reimbursement systems,

developing contractual relationships, understanding and managing the financial risks for no-shows and

uninsured patients, recruiting providers, and managing a rural behavioral health practice.

Assessing Local System of Care Capacity and Resources

Psychiatrists (particularly child and adolescent) willing to develop a telebehavioral health practice are a

scarce resource. The key question is how best to use this and other scarce resources to enhance access to

care and improve the functioning of the local system of care? A key starting point is to undertake an

assessment of the behavioral health needs of the local system. Conduct an inventory of local behavioral

health resources to identify all relevant providers of services, assess their role in the system of care, explore

their capacity to serve additional patients, and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses.

Use the results of the assessment to determine how telebehavioral health services can best be integrated

into the system of care by providing:

Direct services (e.g., evaluation and medication management, therapy) to children, adolescents, and

family with complex needs;

Peer support services;

Consultative services to support system of care providers in managing less complex clients;

Educational and technical assistance services to enhance the capacity of the system of care to

recognize and manage behavioral health conditions; and

Care management and treatment team management services to coordinate and improve the quality

of care provided.

Using the assessment data, system of care leaders can decide how to best allocate scarce psychiatric

resources to supplement existing resources and maximize system performance.

Understanding Reimbursement and Scope of Practice Policies

The extent to which direct care and consultative services are reimbursable when provided through

telebehavioral health must be understood for the primary third party payers covering the children,

adolescents, and families served by local systems of care. Policies vary across third party payers. Will

individual third party payers reimburse for behavioral health services (including facility fees paid to

originating sites)? Is reimbursement limited to certain settings of care or licensure types? For example,

Medicare, although not a significant payer source for child and adolescent services, limits reimbursement for

telebehavioral health to services provided to residents of rural, underserved areas and limits its payment for

mental health services to physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, licensed clinical social

workers, and doctoral level psychiatrists. Medicaid programs will often include other types of counselors as

reimbursable providers. Armed with this knowledge, systems of care can make informed staffing decisions to

maximize program revenues.

5 | Evidence-Informed Practice in Systems of Care: Misconceptions and Facts

Direct care telebehavioral health services are reimbursable through Medicare, many Medicaid programs, and

some commercial third party payers. However, the existing fee for service payment system can hamper the

sustainability of telebehavioral health services. There is a trend toward accountable care organizations,

capitated Medicaid programs such as Arizonas Regional Behavioral Health Authorities, and other

arrangements where the system of care has responsibility for a defined population of individuals (such as

care management entities serving children with intensive service needs). Such arrangements, through use of

more flexible financing arrangements such as capitation and case rates, can simplify the use and

sustainability of telebehavioral health services. The systems can use existing psychiatric and specialty

behavioral health resources as necessary to serve covered populations without the limitations of fee for

service systems.

Team Building

Given ongoing shortages of child and adolescent psychiatrists, programs should consider building treatment

teams to best use existing skill sets. All members of the treatment team, both at the originating and distant

sites, should, to the greatest extent possible, operate at the top of their licenses. Child and adolescent

psychiatrists should be used to: provide direct care to the most complex patients; consult with other

providers to facilitate treatment of children with less complex issues; and assist in developing the capacity of

the treatment team to serve the system of cares client base. The service provider should become familiar

with the culture and context of the system of care, the child and family population, and the local support

programs including schools, social service agencies, and other resources.

Practice Management

Effective delivery of telebehavioral health services requires strong practice management oversight. Although

the technological demands have become less onerous, telebehavioral health is not a relatively simple

turnkey operation. Significant planning, including the development of a business plan with financial

projections, is required to ensure the successful implementation of what is essentially a new service line for

the system of care. Important considerations involve the development of billing and coding systems,

scheduling staffing, enrolling clinicians in provider panels, and managing patient records. A key consideration

is management of access by vulnerable populations including low income, uninsured, and under-insured

individuals, as well as racially, culturally and linguistically diverse populations. The system must determine,

in advance, the extent to which it can afford to provide free and discounted care and how eligibility for and

access to that care will be determined and managed.

Contracting and Risk Sharing

The provision of telebehavioral health frequently involves the development of a contractual arrangement

between the behavioral provider (the distant site where the clinician is located) and the site where the

patients are located (the originating site, i.e., the purchaser of the service, such as a Rural Health Clinic,

Federally Qualified Health Center, or community mental health center). Key decision points that must be

explored include the hours of operation, the level and types of services provided (e.g., fee-for-service, team

management, consultative services) cost, responsibility for billing for services and registration of providers in

relevant provider panels, and the provision of vacation and on-call coverage. There seems to be an evolving

trend in which the behavioral health providers seek to contract with the originating sites for set blocks of

time. This shifts the burden of practice management and the financial risk to the originating site. How well

this works depends on the capacity of the originating site to assume and manage this risk. As illustrated in

our case examples, it is possible for the behavioral health providers and originating sites to share some of the

risk of operating the service. It is important, however, that these issues be identified and reflected in the

contractual agreements.

Enhancing System Capacity

Telebehavioral health technology can be used to enhance system capacity through training, support, and

supervision of clinicians and staff in the originating sites. This maximizes the use of available scare

psychiatric and specialty behavioral health resources. This has become an integral part of the Eastern

Montana Telehealth Network, Teleconnect Therapies, and University of Virginia systems. We also observed

this trend among a larger cohort of telemental health programs in our earlier study. While these capacity

building activities are not reimbursable services, their costs must be weighed in light of potential

6 | Evidence-Informed Practice in Systems of Care: Misconceptions and Facts

improvements in overall system performance. The challenge involves the sources of funding for these

services. Eastern Montana covers these services through the membership fees paid by participants.

Teleconnect Therapies provides these services under the fees paid by participants for their negotiated

number of visits. The University of Virginia providers these services under the fees paid by participants for

services as well as through their residency training programs. The keys are to ensure that these services add

value to the relationship between the originating sites and the telehealth vendor organizations; that the

originating sites (that are the purchasers of services through network participation or contracts with the

telehealth vendors recognize and appreciate the value-added; and that the services support the viability of

the telehealth services at the community level.

Concluding Thoughts

Although the implementation of telebehavioral health has lagged behind the enthusiasm for its use, there is a

growing understanding of how it can be used to enhance access and improve system capacity. Telebehavioral

health can be sustainable in a fee for service environment if there is careful management and adequate

reimbursement by third party payers to providers for telebehavioral health services. The business case

becomes stronger as we move towards population focused systems of care, such as accountable care

organizations, managed behavioral health plans; and care management entities serving children with

intensive behavioral health needs, in which reimbursement is tied to the care of defined populations rather

than traditional fee for service payment systems. Free from the constraints of fee for service reimbursement,

telebehavioral health allows resources to be allocated to best meet the needs of covered lives regardless of

where they may be.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Lambert, D, Gale, JA, Hansen, A, Croll, Z, & Hartley, D. Telemental health in todays rural health system. Research and Policy Brief #

51, December 2013. Maine Rural Health Research Center. Muskie School for Public Service. University of Southern Maine.

http://muskie.usm.maine.edu/Publications/MRHRC/Telemental-Health-Rural.pdf.

Costello, EJ, He, J, Sampson, NA, Kessler, RC, & Ries Merikangas, K. Services for adolescents with psychiatric disorders: 12-Month

Data from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent. Psychiatric Services, 2014; 65(3): 359-366.

Goldstein, E & Myers, K. Telemental health: A new collaboration for pediatricians and child psychiatrists. Pediatric Annals, 2014;

43(2): 79-84.

Elford, DR, White, H, Bowering, R, Ghandi, A, Maddiggan, B, & St. John, K. A randomized, controlled trial of child psychiatric

assessments conducted using videoconferencing. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 2000; 6(2):73-82.

Nelson, EL, Barnard, M, & Cain. S. Treating childhood depression over videoconferencing. Telemedicine Journal & E-Health, 2003;

9(1): 49-55.

Myers, KM, Vander-Stoep, A, Zhou, C, McCarty, CA, & Katon, W. Effectiveness of a telehealth service delivery model for treating

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A community-based randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child

& Adolescent Psychiatry. Available online 2015, January 29, doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.009 (In press, corrected proof).

Xie, Y, Dixon, JF, Yee, OM, Zang, J, Chen, YA, Deangelo, S, Yellowlees, P, Hendren, R, & Schweitzer, JB. A study on the effectiveness of

videoconferencing on teaching parent training skills to parents of children with ADHD. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 2013;

19(3): 192-199.

ABOUT THE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE NETWORK FOR CHILDRENS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH

The Technical Assistance Network for Childrens Behavioral Health (TA Network), funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, Child, Adolescent and Family Branch, partners with states and communities to develop the most effective and sustainable

systems of care possible for the benefit of children and youth with behavioral health needs and their families. We provide technical assistance

and support across the nation to state and local agencies, including youth and family leadership and organizations.

This resource was produced by the Maine Rural Health Research Center in its role as a contributor to the Clinical Distance Learning Track of the

National Technical Assistance Network for Childrens Behavioral Health.

Вам также может понравиться

- Data Makes the Difference: The Smart Nurse's Handbook for Using Data to Improve CareОт EverandData Makes the Difference: The Smart Nurse's Handbook for Using Data to Improve CareОценок пока нет

- Mobile Technologies & Community Case Management: Solving The Last Mile in Health Care DeliveryДокумент22 страницыMobile Technologies & Community Case Management: Solving The Last Mile in Health Care DeliveryHelen Rocio MartínezОценок пока нет

- A Guide To Getting Started in TelemedicineДокумент405 страницA Guide To Getting Started in TelemedicineAnthony WilsonОценок пока нет

- Evidence-Informed Practice in Systems of Care: Misconceptions and FactsДокумент9 страницEvidence-Informed Practice in Systems of Care: Misconceptions and FactsThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- 1ausing Information Systems To Improve Population Outcomes Concepts in Program Design and Development Structure SystemsДокумент7 страниц1ausing Information Systems To Improve Population Outcomes Concepts in Program Design and Development Structure Systemsapi-678571963Оценок пока нет

- Telepsychiatry in The 21 Century: Transforming Healthcare With TechnologyДокумент17 страницTelepsychiatry in The 21 Century: Transforming Healthcare With TechnologyEngr Gaddafi Kabiru MarafaОценок пока нет

- Telepsychiatry: Effective, Evidence-Based, and at A Tipping Point in Health Care Delivery?Документ34 страницыTelepsychiatry: Effective, Evidence-Based, and at A Tipping Point in Health Care Delivery?Riza Agung NugrahaОценок пока нет

- Pediatric-Telemedicine 2022 YyapdДокумент11 страницPediatric-Telemedicine 2022 YyapdLОценок пока нет

- The Future of PCMH PDFДокумент12 страницThe Future of PCMH PDFiggybauОценок пока нет

- Quiz#3: Filipino Culture, Technologies, and ValuesДокумент4 страницыQuiz#3: Filipino Culture, Technologies, and ValuesG MОценок пока нет

- Tizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Документ4 страницыTizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Royce Vincent TizonОценок пока нет

- NURS FPX 6616 Assessment 2 Summary Report On Rural Health Care and Affordable SolutionsДокумент7 страницNURS FPX 6616 Assessment 2 Summary Report On Rural Health Care and Affordable SolutionsEmma WatsonОценок пока нет

- Tizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Документ4 страницыTizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Royce Vincent TizonОценок пока нет

- Communication in Health - Lecture ScriptДокумент6 страницCommunication in Health - Lecture ScriptJibril AbdulMumin KamfalaОценок пока нет

- A Qualitative Study of Health Care Providers' Perceptions and Experiences of Working Together To Care For Children With Medical Complexity (CMC)Документ2 страницыA Qualitative Study of Health Care Providers' Perceptions and Experiences of Working Together To Care For Children With Medical Complexity (CMC)Lindon Jay EnclunaОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Recent AdvancementДокумент2 страницыPediatric Recent AdvancementAnonymous ceYk4p4Оценок пока нет

- Telemedicine in Rural KenyaДокумент6 страницTelemedicine in Rural KenyaKamau GabrielОценок пока нет

- Telepsychiatry TodayДокумент9 страницTelepsychiatry Todayn1i1Оценок пока нет

- (Sample) TelemedicineДокумент7 страниц(Sample) TelemedicineCherilyn MedalleОценок пока нет

- The Role of Informatics in Promoting PatientДокумент9 страницThe Role of Informatics in Promoting Patientapi-242114301100% (1)

- Telemedicine Feasibility Study Report and Business CaseДокумент22 страницыTelemedicine Feasibility Study Report and Business CaseDulce FigueraОценок пока нет

- Tugas MR Reza UASДокумент4 страницыTugas MR Reza UASUmiKulsumОценок пока нет

- 2019 LeapfrogToValue PDFДокумент57 страниц2019 LeapfrogToValue PDFJamey DAVIDSONОценок пока нет

- Doctoral Capstone Needs Assessment: I Believe in ClientДокумент8 страницDoctoral Capstone Needs Assessment: I Believe in Clientapi-595108452Оценок пока нет

- ISQua 2018Документ4 страницыISQua 2018Mari Lyn100% (1)

- Effect of The Planned Therapeutic CommunicationДокумент12 страницEffect of The Planned Therapeutic CommunicationsherlyОценок пока нет

- Artikel Sistem Informasi KepДокумент11 страницArtikel Sistem Informasi KepM.Ichwan RijaniОценок пока нет

- The Digital Divide at An Urban Community Health CenterДокумент12 страницThe Digital Divide at An Urban Community Health CenterRizza DeaОценок пока нет

- Telepsychiatry For Mental Health Service Delivery To Children and AdolescentsДокумент7 страницTelepsychiatry For Mental Health Service Delivery To Children and Adolescentsleslieduran7Оценок пока нет

- Innovation Awards Round 2 Batch 1Документ7 страницInnovation Awards Round 2 Batch 1iggybauОценок пока нет

- Annotated Bibliography PDFДокумент10 страницAnnotated Bibliography PDFapi-296283530Оценок пока нет

- Part B: The Feasibility and Acceptability of Mi SMART, A Nurse-Led Technology Intervention For Multiple Chronic ConditionsДокумент10 страницPart B: The Feasibility and Acceptability of Mi SMART, A Nurse-Led Technology Intervention For Multiple Chronic Conditionsindah sundariОценок пока нет

- Prelim Exam Block 2 Group 3Документ5 страницPrelim Exam Block 2 Group 3Sufina AnnОценок пока нет

- Familywelfareservices 190329102006Документ26 страницFamilywelfareservices 190329102006karunamightymech306Оценок пока нет

- The Use of Reproductive Healthcare at Commune Health Stations in A Changing Health System in VietnamДокумент9 страницThe Use of Reproductive Healthcare at Commune Health Stations in A Changing Health System in VietnamjlventiganОценок пока нет

- Press Release 12-09 - New Study Raises Health and Safety Concerns inДокумент3 страницыPress Release 12-09 - New Study Raises Health and Safety Concerns inhealthoregonОценок пока нет

- PCP CC Addendum WebДокумент24 страницыPCP CC Addendum WebPatient-Centered Primary Care CollaborativeОценок пока нет

- Student Mental Health & Peer-Support Program (MHAPS) : 9th February 2015 Edward Pinkney, Hong Kong UniversityДокумент13 страницStudent Mental Health & Peer-Support Program (MHAPS) : 9th February 2015 Edward Pinkney, Hong Kong UniversityEd PinkneyОценок пока нет

- Informatics (Requirements)Документ4 страницыInformatics (Requirements)aninОценок пока нет

- Reaction Paper To E-HealthДокумент2 страницыReaction Paper To E-HealthArian May MarcosОценок пока нет

- Nursing Informatics FinalsДокумент7 страницNursing Informatics FinalsAlyОценок пока нет

- Telehealth Research and Evaluation Implications For Decision MakersДокумент9 страницTelehealth Research and Evaluation Implications For Decision Makerscharlsandroid01Оценок пока нет

- Meyer-Grieve James Et AlДокумент9 страницMeyer-Grieve James Et Aljolamo1122916Оценок пока нет

- The Business of Nur$ing: Telemedicine, DEA and FPA guidelines, A Toolkit for Nurse Practitioners Vol. 2От EverandThe Business of Nur$ing: Telemedicine, DEA and FPA guidelines, A Toolkit for Nurse Practitioners Vol. 2Оценок пока нет

- Farzad Mostashari, M.D., SC.M.: Helping Providers Adopt and Meaningfully Use Health Information TechnologyДокумент18 страницFarzad Mostashari, M.D., SC.M.: Helping Providers Adopt and Meaningfully Use Health Information TechnologyBrian AhierОценок пока нет

- A Guide To Getting Started in TelemedicineДокумент405 страницA Guide To Getting Started in Telemedicineapi-3799052Оценок пока нет

- Family PlanningДокумент4 страницыFamily Planningfayetish100% (2)

- Southeastern Minnesota Beacon CommunityДокумент3 страницыSoutheastern Minnesota Beacon CommunityONC for Health Information TechnologyОценок пока нет

- P TeledentistryДокумент3 страницыP Teledentistrypooja singhОценок пока нет

- Police Mental Health CollaborationsДокумент24 страницыPolice Mental Health CollaborationsEd Praetorian100% (3)

- Perceptions of The Benefits of Telemedicine in Rural CommunitiesДокумент13 страницPerceptions of The Benefits of Telemedicine in Rural CommunitiesIshitaОценок пока нет

- Module 14Документ5 страницModule 14camille nina jane navarroОценок пока нет

- Summary of Purposes and ObjectivesДокумент19 страницSummary of Purposes and Objectivesrodolfo opido100% (1)

- Ehealthandqualityinhealthcare ImplementationtimeДокумент5 страницEhealthandqualityinhealthcare Implementationtimealex kimondoОценок пока нет

- Bahasa Inggris KesehatanДокумент3 страницыBahasa Inggris KesehatanSevardonОценок пока нет

- Research Paper Topics On Child WelfareДокумент11 страницResearch Paper Topics On Child Welfarefvfr9cg8100% (1)

- ASS134 FeДокумент6 страницASS134 Febright osakweОценок пока нет

- Benefits OfTelemedicineДокумент6 страницBenefits OfTelemedicineMurangwa AlbertОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1Документ7 страницChapter 1Jeremias Cruz CalaunanОценок пока нет

- Telemental Health: Clinical, Technical, and Administrative Foundations for Evidence-Based PracticeОт EverandTelemental Health: Clinical, Technical, and Administrative Foundations for Evidence-Based PracticeОценок пока нет

- Meeting the Needs of Older Adults with Serious Illness: Challenges and Opportunities in the Age of Health Care ReformОт EverandMeeting the Needs of Older Adults with Serious Illness: Challenges and Opportunities in the Age of Health Care ReformAmy S. KelleyОценок пока нет

- Evidence-Based Programs To Meet Mental Health Needs of California Children and YouthДокумент1 страницаEvidence-Based Programs To Meet Mental Health Needs of California Children and YouthThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Early Psychosis Intervention Directory, V4Документ50 страницEarly Psychosis Intervention Directory, V4The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Evidence-Informed Practice in Systems of Care: Frameworks and Funding For Effective ServicesДокумент9 страницEvidence-Informed Practice in Systems of Care: Frameworks and Funding For Effective ServicesThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderДокумент5 страницAttention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Child Welfare and Systems of Care Opportunities For PartnershipДокумент4 страницыChild Welfare and Systems of Care Opportunities For PartnershipThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 3Документ6 страницCase Western Brief 3The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Notable News May 5, 2015Документ2 страницыNotable News May 5, 2015The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Notable News May 5, 2015Документ2 страницыNotable News May 5, 2015The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 4Документ5 страницCase Western Brief 4The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 2Документ5 страницCase Western Brief 2The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 5Документ6 страницCase Western Brief 5The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 1Документ3 страницыCase Western Brief 1The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Resiliency and Self Care BrochureДокумент2 страницыResiliency and Self Care BrochureThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Integrating System of Care and EducationДокумент2 страницыIntegrating System of Care and EducationThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- JJ Brief 1Документ7 страницJJ Brief 1The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- JJ Brief 1Документ7 страницJJ Brief 1The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- JJ Brief 2 FinalДокумент7 страницJJ Brief 2 FinalThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- JJ Brief 2Документ8 страницJJ Brief 2The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Autism Spectrum Disorders BriefДокумент6 страницAutism Spectrum Disorders BriefThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Screening and Assessment BriefДокумент3 страницыScreening and Assessment BriefThe Institute for Innovation & Implementation100% (1)

- TA Network BrochureДокумент2 страницыTA Network BrochureThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 3Документ6 страницCase Western Brief 3The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 4Документ5 страницCase Western Brief 4The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 5Документ6 страницCase Western Brief 5The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 1Документ3 страницыCase Western Brief 1The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Case Western Brief 2Документ5 страницCase Western Brief 2The Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

- Organizational Readiness and Capacity Assessment IIДокумент2 страницыOrganizational Readiness and Capacity Assessment IIThe Institute for Innovation & ImplementationОценок пока нет

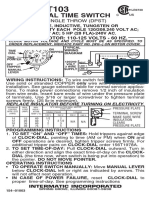

- T103 InstructionsДокумент1 страницаT103 Instructionsjtcool74Оценок пока нет

- Project Report On MKT Segmentation of Lux SoapДокумент25 страницProject Report On MKT Segmentation of Lux Soapsonu sahОценок пока нет

- 2013 Casel GuideДокумент80 страниц2013 Casel GuideBobe MarinelaОценок пока нет

- Traditional Christmas FoodДокумент15 страницTraditional Christmas FoodAlex DumitracheОценок пока нет

- Piaget Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentДокумент2 страницыPiaget Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentSeph TorresОценок пока нет

- 9 - 1 H Wood Cabinet Spec Options NelДокумент8 страниц9 - 1 H Wood Cabinet Spec Options NelinformalitybyusОценок пока нет

- Design and Fabrication of Floor Cleaning Machine - A ReviewДокумент4 страницыDesign and Fabrication of Floor Cleaning Machine - A ReviewIJIERT-International Journal of Innovations in Engineering Research and Technology100% (1)

- PC110R 1 S N 2265000001 Up PDFДокумент330 страницPC110R 1 S N 2265000001 Up PDFLuis Gustavo Escobar MachadoОценок пока нет

- Sore Throat, Hoarseness and Otitis MediaДокумент19 страницSore Throat, Hoarseness and Otitis MediaainaОценок пока нет

- Agriculture and FisheryДокумент5 страницAgriculture and FisheryJolliven JamiloОценок пока нет

- Electrolux EKF7700 Coffee MachineДокумент76 страницElectrolux EKF7700 Coffee MachineTudor Sergiu AndreiОценок пока нет

- Consolidation of ClayДокумент17 страницConsolidation of ClayMD Anan MorshedОценок пока нет

- Secrets of Sexual ExstasyДокумент63 страницыSecrets of Sexual Exstasy19LucianОценок пока нет

- Helicopter Logging Operations - ThesisДокумент7 страницHelicopter Logging Operations - ThesisAleš ŠtimecОценок пока нет

- Lpalmer ResumeДокумент4 страницыLpalmer Resumeapi-216019096Оценок пока нет

- Culturally Safe Classroom Context PDFДокумент2 страницыCulturally Safe Classroom Context PDFdcleveland1706Оценок пока нет

- This Study Resource WasДокумент3 страницыThis Study Resource WasNayre JunmarОценок пока нет

- Inside The Earth NotesДокумент2 страницыInside The Earth NotesrickaturnerОценок пока нет

- LapasiДокумент3 страницыLapasiWenny MellanoОценок пока нет

- Red Winemaking in Cool Climates: Belinda Kemp Karine PedneaultДокумент10 страницRed Winemaking in Cool Climates: Belinda Kemp Karine Pedneaultgjm126Оценок пока нет

- Air Compressors: Instruction, Use and Maintenance ManualДокумент66 страницAir Compressors: Instruction, Use and Maintenance ManualYebrail Mojica RuizОценок пока нет

- Supply ForecastingДокумент17 страницSupply ForecastingBhavesh RahamatkarОценок пока нет

- Ryder Quotation 2012.7.25Документ21 страницаRyder Quotation 2012.7.25DarrenОценок пока нет

- PNFДокумент51 страницаPNFMuhamad Hakimi67% (3)

- Keith UrbanДокумент2 страницыKeith UrbanAsh EnterinaОценок пока нет

- Osma Osmadrain BG Pim Od107 Feb 2017pdfДокумент58 страницOsma Osmadrain BG Pim Od107 Feb 2017pdfDeepakkumarОценок пока нет

- Epidemiology of Injury in Powerlifting: Retrospective ResultsДокумент2 страницыEpidemiology of Injury in Powerlifting: Retrospective ResultsJavier Estelles MuñozОценок пока нет

- Respiratory Examination - Protected 1Документ4 страницыRespiratory Examination - Protected 1anirudh811100% (1)

- Gut Health Elimination Diet Meal Plan FINALДокумент9 страницGut Health Elimination Diet Meal Plan FINALKimmy BathamОценок пока нет

- Fire BehaviourДокумент4 страницыFire BehaviourFirezky CuОценок пока нет