Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

ContinuousPositive Airway Pressure and Nasal Trauma in Neonates: A Descriptive Prospective Study

Загружено:

IOSRjournalОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ContinuousPositive Airway Pressure and Nasal Trauma in Neonates: A Descriptive Prospective Study

Загружено:

IOSRjournalАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS)

e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 14, Issue 11 Ver. IV (Nov. 2015), PP 110-116

www.iosrjournals.org

ContinuousPositive Airway Pressure and Nasal Trauma in

Neonates: a descriptive prospective study

Professor Dr.NumanNafie Hameed (FRCPCH, FIBMS, MRCPCH, MAAP, DCH)1,2,

Dr. RaiessYousif Raiees (MBChB)2

1. Department of Pediatrics, College of medicine, Baghdad University, Baghdad

2. Children welfare teaching hospital, medical city, Baghdad, Iraq

Correspondence: Professor Dr. NumanNafie Hameed - College of Medicine, Baghdad University, and

Consultant pediatrician in Children Welfare Teaching Hospital, Medical City Complex, Bab Al-Muadham, PO

box 61023, Code, 12114 Baghdad (Iraq).

Abstract: Objectives:This study aimedto evaluate the frequency and severity of nasal trauma secondary to

nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP) in neonates.

Methods: This is a prospective observational study carried out in the Neonatal Care Unit (NCU) of Baghdad

teaching hospital,maternity ward, Medical City, Baghdad, Iraq. The study included newborns that underwent

NCPAP with prongs on admission and those receiving NCPAP after weaning from ventilation, from 1st March,

2014 - 1st July, 2014. Patients noses were monitored from the first day of NCPAP treatment until its weaning.

Nasal trauma was reported into three stages: (I) persistent erythema; (II) superficial ulceration; and (III)

necrosis.

Results:Two hundred ten newborns (130 males, 80 females) were enrolled.Mean gestational age was 333.5

weeks (SD), mean birth weight 2044 765g (SD). All patients had some degree of nasal trauma with stage I, II

and III in 93 (44.3%), 52 (24.8%) and 65 (31.0%) patients, respectively. Frequency and severity of trauma were

inversely correlated with gestational age and birth weight. Severe lesion(stageIII)was significantly and directly

positively correlated with the total duration on NCPAP (P<0.00). The risk of nasal trauma was greater in

neonates <32 weeks of gestational age, weighing <1500 g at birth,requiringlarger nasal prong size or smaller

head caps and/or requiringNCPAP>2 days.

Conclusions: Nasal trauma is a frequent complication of NCPAP, especially in smaller preterm babies and in

babies requiring larger nasal prongs or longer NCPAP application.

Keywords:Continuous positive airway pressure, nasal trauma, neonates

I. Introduction

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) has provided an exciting therapy for treating respiratory

distress (RDS) in the newborn. Its primary function is to establish/maintain open airways. The circuit is

structured such that a continuous flow of humidified oxygen in combination with other compressed gases is

delivered to the infants often with nasal prongs or masks(1).

The CPAP goal is accomplished by supplying about 4 8 cmH2O positive airway pressure into infant`s

[2]

airway .To apply this pressure system, three component are essential: continuous flow of a heated and

humidified gas mixture (compressed air and oxygen); a system connecting the device to the patient`s airway

such as facial masks, nasal prongs, nasopharyngeal or endotracheal tubes and a mechanism of positive pressure

generation in thesystem [3-4].

A nasal prong is the most common deviceused because it is a less invasive way of supplying CPAP [3],

typically called nasal CPAP or NCPAP.It is available in different sizes and usually made of light flexible

material [4]. Despite its advantage, this device can harm the nostrils and cause discomfort and disfiguration in the

long term [5].

The local pressure of NCPAP devices may lead to decubitus lesions in the newborn due to its

cutaneous vulnerability and anatomical factors such as end - vascularization of the columella and nostrils [6].In

addition,nasal trauma represents a source of discomfort for patient, possible site of infection and a risk of long

term functional or cosmetic sequelae [7-8].

Research classifies nasal injuries caused by the use of prongs in three stages: mild, moderate and

severe: The mild stage (I) is described as redness or nasal hyperemia; the moderate (II) presents bleeding

injuries and the severe stage (III) refers to injuries with necrosis [9].

Local irritation and trauma to the nasal septum may occur due to misalignment or improper fixation of

nasal prongs [10]. Breakdown and erosion low on the septum at the base of the philtrum can occur when using

nasal masks or prongs, and columella necrosis can occur after only short periods of receiving NCPAP. Nasal

DOI: 10.9790/0853-14114110116

www.iosrjournals.org

110 | Page

Continuouspositive Airway Pressure And Nasal Trauma In Neonates: A Descriptive Prospective

snubbing and circumferential distortion (widening) of the nares can be caused by nasal prongs, especially if

NCPAP is being used for more than just a few days. Inadequate humidification can lead to nasal mucosal

damage [11].

In Baghdad, Iraq, a few studiesof the use of CPAP in neonates but to the best of our knowledge, no

study about nasal trauma after CPAP in neonates in Baghdad has been published.[12] Thisobservational

prospective study aimed to fill this research gap by determiningthe frequency and severity of nasal trauma

secondary to NCPAPwith prongs in neonatal care unit in maternity ward of Baghdad teaching hospital.

II. Methods

This descriptive prospective study was carried out in the Neonatal Care Unit (NCU) of Baghdad

teaching hospital maternity ward.The Ethical committee of the hospital approved this study.One of the research

team(RYR) observed the neonates withtheresponsible nurses help to observe nasal injuries without touching

them.

The study included newborns that underwent NCPAP with prongs on admission and those receiving

NCPAP after weaning from ventilation, from 1st March, 2014 - 1st July, 2014. The sample size was 210

newborns. They were prospectively observed to detect nasal trauma from the first day of NCPAP treatment until

its weaning.

Standard policy in our NCU is to promote the routine use of NCPAP within minutes after birth for all

newborns with respiratory distress regardless of etiology. Pressure of 4 - 6 cmH2O is maintained and oxygen is

adjusted to keep PaO2 >50mm Hg. Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation are considered when

NCPAP is not sufficient to achieve a satisfactory PaO2 while breathing 80100% O2 and/or lower the PaCO2

<65 mm Hg, or to relieve marked retractions or frequent apneas. Weaning NCPAP is considered when the

tachypnea and retractions become minimal or have disappeared and when there is no longer need for

supplemental oxygen. NCPAP is reintroduced when the infant has tachypnea >70/min, deep retractions or

frequent episodes of apnea and bradycardia.

Throughout the study period, the same NCPAP system was used (Fisher and PayKel Bubble-CPAP

system BC 161, New Zealand, UK ). This system involves a source of gas flow (6-8 L /min), air oxygen

blender, humidifier (MR85,Fisher& Paykel Health Care, New Zealand) and respiratory circuit. Nasal tubing

(Flexi trunk) and nasal prongs and masks were alternativelyusedto deliver CPAP. A transparent template is

available from Fisher-Paykel to suggest appropriate nasal prong-size according to the circumference of the nasal

cavity and the width of the septumwas used to determine the size of prongs needed for each infant. Generally

using these guidelines: neonates <1000 g required 35/20; neonates 1000 2000 g required 40/30, and neonates

1500 2499 g required 50/40. The prongs were positioned at least 2 mm from the septum to avoid pressure

necrosisand were secured using a head cap and Velcro felt. [13]

Infant were positioned supine, prone or on their sides generallyflexed.Nursing care included gentle

massages of pressure points of nasal devices every 24 hrwithout any ointment. When a nasal trauma was noted,

an ointment (sodium fusidate 20 mg) was applied with massages. In case of persistent trauma or increased in

severity, a piece of cotton was placed between pressure points and NCPAP devices.

To collect and establish lesions caused by the NCPAP prongs, the stage of lesions, use of protection,

number and type of prongs used, the nurse and researcher took the prongs out of newborns nostrils briefly,

checked their nostrils and immediately replace the prongs. Because inspection was external and not

instrumented, it waspossible to miss isolated internal trauma of the nostrils. Other complimentary data were

extracted from the neonatology charts, medical evolution records and nursing files.

There is currently no widely recognized classification available to describe the severity of nasal trauma

secondary to NCPAP in neonates. We therefore classified trauma based on the standardized classification of

decubitus lesions from the US National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) [14,15].Stage I: erythema not

blanching, on an otherwise intact skin. Stage II: superficial ulcer or erosion, with partial thickness skin loss.

Stage III: necrosis, with full thickness skin loss. When a patient presented with a nasal trauma of different

stages, only the most severe stage was used.

Statistical analysis:Data were analyzed by using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 21.

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean, standard deviation (SD), frequencies (NO.) and percentages (%).

Chi square testing was used to assess the significance of the association between categorical variables

(frequencies). Students t test was used to compare two means while ANOVA test (analysis of variances) was

used to compare three means. Level of significance (p. value) <0.05 was considered significant. Finally results

and findings were presented in tables and figures with explanatory paragraphs.

DOI: 10.9790/0853-14114110116

www.iosrjournals.org

111 | Page

Continuouspositive Airway Pressure And Nasal Trauma In Neonates: A Descriptive Prospective

III. Results

A total of 210 neonates were enrolled in this study.The mean gestational age was 33.2 3.5 weeks

(range: 25 40). Sixteen neonates (7.6%) had gestational age of < 28 weeks, 69 (32.9%) were 28 32 weeks,

81 (38.6%) were 33 36 weeks and 44 (21%) were 37 weeks.One-Thirty neonates (61.9%) were males versus

80 (38.1%) females. Birth weight ranged from 650 to 3900 grams with a mean of 2044 765 grams. From

these,14 neonates (6.7%) weighed < 1000 gm, 121 (57.6%) weighed 1000 2499 gm, and 75 (35.7%) weighed

2500 gm.

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) was the most frequent indication for NCPAP occurring in 144

(68.6%) while 62 (29.5%) had transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN), and only 2 had apnea of prematurity

and 2 needed respiratory support post extubation.All patients had some degree of nasal trauma with stage I, II

and III in 93 (44.3%), 52 (24.8%) and 65 (31.0%) patients, respectively.

The cross-tabulation (Table 1) between gestational age categories and the lesion stage, and also the

comparison of mean gestational age and stage of the lesion revealed an inverse (negative) but significant

correlation. Additonally, neonates who had a lower gestational age had significantly more severe lesions.

Furthermore the mean gestational age of those neonates with stage 1(mild) lesions was significantly higher than

those with moderate (stage II) and/or severe lesions (stage III) (Fig.1).

There was a significant inverse correlation between the birth weight and stage of the lesion,both

compared as categories or mean along the stages, P<0.001, (Table 2& Fig .2).

There was a direct (positive) significant correlation between the lesion stage and size of nasal piece

(P=0.023). A significant inverse correlation had been found between severity of lesion and the size of head cap

(P<0.001).(Table3)

There was no statistically significant association between the age CPAP was applied and the lesion

stages (P=0.32). Neonates with moderate lesion had the higher mean age when put on CPAP than those with

stage I and stage III, respectively, (P<0.001).

A significant association was found between the age when injury developed and the lesion stages.

The lesion stage was significantly and directly (positive correlation) correlated with the total duration

on CPAP, with severe lesion (stage III)requiring longer duration of NCPAP, (P<0.00), (Table 4 and Fig.3).

IV. Discussion

Nasal CPAP is the preferred means of ventilatory support for most neonates with respiratory distress.

Complications can thus be expected and should be looked for and quantified whenever possible. To date, there

are limited reports in the literature regarding intranasal complications [14].

Comparisons between published studies are difficult because of highly variable descriptions and

definitions of nasal trauma, which can differ in severity from limited local redness to full necrosis. We proposed

a simple and reproducible classification system including three stages adapted from the general classification of

the US NPUAP [14, 15].

The most frequent indication of NCPAP in our study was RDS (68.6%) followed by TTN (29.5%).

These result differ from those of Fischer et al [16], which reveal TTN in the majority of cases (43%), followed

by,aspiration syndrome (30%) and RDS (9%). This may be due to high rate of premature deliveries, elective

cesarean section delivery. The difference in etiologies might effect the rates of different stages of nasal trauma

between locations but this would need require further studies.

The nasal trauma secondary to NCPAP was a frequent complication in our neonates. Stage I lesions

were seen in (44.3%), (stage II) in (24.8%) and (stage III) in (31.0%). These result differ from Nascimento et al

[17]

, who found stage I in 79.6%, stage II in 19.7% and stage III in 0.7% of their neonates.

We postulate that the formation of nasal lesions may be related to health professionals inappropriately

fixing the prongs into the newborns nostrils. More severe damage would be expected if the entire prongs are

inserted such that the device is in direct contact with the columella. In this study, no nasal protection was used,

while it was used in (96.6%) of patients in the study by Nascimento et al [17].

More severe lesions would be expected without the use of protection. Addtionally, inappropriately

small prongs may move more inside the nostrils causing more damage to the septum.

Because of our limited supply of prongs, we could not use new prongs each time therefore, we had to

disinfect our prongs between use Addtionally, we did not exchange and sterilization the system every two

days as recommended in the literature . Routine disinfection of prongs likely leds to detoriation of the material

making it less flexible, a potential risk factor for the development of nasal lesions [18].

There was an inverse (negative) significant correlation between mean gestational age and the lesion

stage. As expected, neonates with younger gestational age had the more severe lesion, as also seen by Fischer et

al [16] and Alsop et al [19], who found that the frequency and severity of nasal trauma increased with lower

gestational age (> 90% in neonate <32 week of gestational age).

DOI: 10.9790/0853-14114110116

www.iosrjournals.org

112 | Page

Continuouspositive Airway Pressure And Nasal Trauma In Neonates: A Descriptive Prospective

As also expected their was a significant inverse correlation between the birth weight and lesion stage,

in agreement with Fischer et al[16]and Robertson et al [20], who estimated relative risk was significantly higher in

patient weighing < 1500 (25%), (20%) respectively.

There was a direct (positive) significant correlation between the lesion stage and size of nasal piece

(P=0.023), as also found by Nascimento et al [17]. Our limited choice of prong sizes may led to more nasal

lesions. The ideal prong size reported in the literature is one not so large that it distends the nostrils and not so

small that it allows extra space between the prong and nostrils [18]. Even though lesions are still observed with

the correct size of prongs, they are present in a smaller proportion. [21]

In contrast toNascimento et al [17], we found a significant but inverse correlation between severity of

lesion and the size of head cap (P<0.001). One explanation maybe that caps too large for the neonates head may

led to increase tube movement and thus trauma to the nose.Thus, it is advisable to ensure adequate cap sizes

limiting pressure on the nostrils to the minimum[20]. Importantly, when the neonate is premature, low birth

weight and/or has a small head circumference he need small head cup and will likely need more time on CPAP,

resulting in increase risk factors for development of nasal injury. In the absence of caps, bandages were fixed

around the head with patches with the same function immobilizing the prongs also possibly affecting the

severity of the nasal lesions. As much as possible, NCPAP tubing should be positioned on the hat following the

manufacturers recommendations without pressure on the skin, pull on the nasal septum, ensuring the absence of

a brow furrow, (indicative of excessive pressure on the nasal septum)[10].

The lesion stage was significantly and directly (positive correlation) correlated with the total duration

on CPAP with severe lesion (stage III) associated withthe longer duration. This was also found by several other

researhers including Fischer et al [16], Yong et al[21], Nascimento et al [17] and Squires and Hyndman [22],who

concluded the frequency of lesions with the use of CPAP with prongs after a minimum period of two days was

100% and time was a risk factor for the development of lesions[17].

V. Conclusions

Nasal trauma is a frequent complication of NCPAP, especially in preterm neonates with RDS. Risk

factors for advanced stages of nasal lesions includes lower gestational age and birth weight, larger size of nasal

prongs, smaller size of head caps and longer duration on CPAP.

We recommend paying special attention when using NCPAP in preterm and low birth weight neonates

especially those with RDS. Addtionally we recommend ensuring application of appropriate size of prongs and

caps; particularly avoiding the use of prongs and caps which are too small. Finally, when possible shorten the

total duration of NCPAP use.

Declaration of interest:The authors report no declarations of interest

Author's contributions: NNH participated in the study design, sequence alignment and drafting and

finalization of the manuscript and submission to the journal. RYR participated in the study design, data

collection, sequence alignment and drafting and finalization of the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Tina M. Slusher, MD, Associate Professor of Pediatrics, University of

Minnesota-Divsion of Global Pediatrics, Staff Intensivist, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Hennepin County

Medical Center, for her generous reviewing the manuscript.

References

[1].

[2].

[3].

[4].

[5].

[6].

[7].

[8].

[9].

PolinRA,Sahni R. Newer experience with CPAP. Seminar on Neonatology, 2002 Oct.; 7(5):379-89.

Liptsen E, Aghai ZH, Pyon KH, Saslow JG, Nakhla T, Long J, et al. Work of breathing during nasal continuous positive airway

pressure in preterm infants: a comparison of bubble vs. variable-flow devices.J Perinatology 2005; 25(7):453-458.

Kahn DJ, Habib RH, Courtney SE.Effects of flow amplitudes on intraprong pressures during bubble versus ventilator-generated

nasal continuous positive airway pressure in premature infants. Pediatrics 2008; 122(5):1009-1013.

Kaur C, Sema A, Beri RS, Puliyel JM. A simple circuit to deliver bubbling CPAP.IndianPediatr 2008; 45 (4):312-314.

Campbell DM, Shah OS, Shah V, Kelly EN. Administration of the continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) nasal mask versus

nasal prong in premature baby.J. Perinatology 2006 sep.; 26:546-9.

Cartlidge P. The epidermal barrier.SeminNeonatol2000; 5:27380.

Kopelman AE, Holbert D. Use of oxygen cannulas in extremely low birth weight infants is associated with mucosal trauma and

bleeding, and possibly with coagulase-negative staphylococcal sepsis. J Perinatol2003; 23:94.

Smith LP, Roy S. Treatment strategy for iatrogenic nasal vestibular stenosis in young children.Int J PediatrOtorhinolaryngol2006;

70:136973.

Buettiker V, Hug MI, Baenziger O, Meyer C, Frey B. Advantages and disadvantages of different nasal CPAP systems in

newborns.NeonatePed. Intensive Care 2004 Mar.; 30:926-30.

DOI: 10.9790/0853-14114110116

www.iosrjournals.org

113 | Page

Continuouspositive Airway Pressure And Nasal Trauma In Neonates: A Descriptive Prospective

[10].

[11].

[12].

[13].

[14].

[15].

[16].

[17].

[18].

[19].

[20].

[21].

[22].

Loftus BC, Ahn J, Haddad J Jr. Neonatal nasal deformities secondary to nasal continuous positive airway pressure.Laryngoscope

1994; 104(8 Pt 1):1019-1022.

Lee SY, Lopez V. Physiological effects of two temperature settings in preterm infants on nasal continuous airway pressure

ventilation. J ClinNurs 2002;11 (6):845-847.

Hameed NN, Abdul Jaleel RK, Saugstad OD. The use of continuous positive airway pressure in preterm babies with respiratory

distress syndrome: a report from Baghdad, Iraq. J. maternal fetal neonatal medPublished online 19 August 2013, early online: 14.2013 Informa UK Ltd.doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.825595

De Paoli AG, Morley CJ, Davis P.G. Nasal CPAP for neonates: What do we know in 2003?Arch Dis Child Fetal and Neonatal Ed

2003 May; 88(1):f168-72.

The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcer prevalence, cost and risk assessment: consensus development

conference statement.Decubitus 1989; 2: 248.

Black J, Baharestani MM, Cuddigan J, et al. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panels updated pressure ulcer staging system. Adv

Skin Wound Care 2007; 20:26974.

Fischer C, Bertelle V, Hohlfeld J, Forcada-Guex M, Stadelmann-Diaw C, Tolsa JF. Nasal trauma due to continuous positive airway

pressure in neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonate 2010; 95: F447-451.

Nascimento RM, Ferreira ALC, Coutinho ACFP, Verssimo RCSS. The frequency of nasal injury in newborns due to the use of

continuous positive airway pressure with prongs.Rev Latino-am Enfermagem 2009 julho-agosto; 17(4):489-94.

Mazzella M, Bellini C, Calevo MG, Campone F, MassoccoD,Mezzano P, et al. A randomised control study comparing the

InfantFlow Driver with nasal continuous positive airway pressure in preterminfants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2001;

85(2):86-90.

Alsop EA, Cooke J, Gupta S, Sinha SK. Nasal trauma in preterm infants receiving continuous positive airway pressure.Arch Dis

Child 2008; 93: 23.

Robertson NJ, McCarthy LS, Hamilton PA, et al. Nasal deformities resulting from flow driver continuous positive airway pressure.

Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1996; 75: F20912.

Yong SC, Chen SJ, Boo NY. Incidence of nasal trauma associated with nasal prong versus nasal mask during continuous positive

airway pressure treatment in very low birthweight infants: a randomised control study. Arch Dis Child FetalNeonatal Ed 2005;

90:F480483.

Squires A J, HyndmanM.Prevention of nasal injuries secondary to NCPAP application in the ELBW infant. Neonatal Network

2009; 28(1) 13-26.

Table 1: Correlation between gestational age and lesion stage (severity)

Gestational

Age (weeks)

Total

No.

< 28

28 32

33 36

37

Total

Mean SD

16

69

81

28

210

Lesion stage

Stage I

(mild)

no.

%

3

18.8

11

15.9

51

63.0

28

63.6

93

44.3

34.9 3.3

P

Stage II

(moderate)

no.

0

23

21

8

52

33.3 2.8

%

0.0

33.3

25.9

18.2

24.8

Stage III

(severe)

no.

13

35

9

8

65

30.6 3.5

%

81.3

50.7

11.1

18.2

31.0

0.001sig

0.001sig

Table 2: Correlation between lesion stage and birth weight (N=210)

Birth weight (gm)

< 1000

1000 - 2499

2500

Total

Mean SD

Total

No.

14

121

75

210

Lesion stage

Stage I

(mild)

no.

%

3

21.4

38

31.4

52

69.3

93

44.3

2422 688

P

Stage II

(moderate)

no.

1

36

15

52

2010 680

%

7.1

29.8

20.0

24.8

Stage III

(severe)

no.

10

47

8

65

1530 622

%

71.4

38.8

10.7

31.0

<0.001sig

<0.001sig

Table 3: Correlation between lesion stages and size of nasal piece and head cap

Variable

Size of nasal piece

35 - 20

40 - 30

45 - 40

50 - 40

Size of head cap

17- 22

22- 25

25- 29

29- 36

Total

No.

Lesion stage

Stage I

(mild)

no.

%

Stage II

(moderate)

no.

150

24

2

34

57

14

0

22

38.0

58.3

0.0

64.7

24

95

7

84

5

26

2

60

20.8

27.4

28.6

71.4

DOI: 10.9790/0853-14114110116

Stage III

(severe)

no.

41

5

0

6

27.3

20.8

0.0

17.6

52

5

2

6

34.7

20.8

100.0

17.6

0.023

sig

2

33

2

15

8.3

34.7

28.6

17.9

17

36

3

9

70.8

37.9

42.9

10.7

<0.001

sig

www.iosrjournals.org

114 | Page

Continuouspositive Airway Pressure And Nasal Trauma In Neonates: A Descriptive Prospective

Table 4: Distribution of mean age of put on CPAP, age at injury developed and duration on CPAP

according to the lesion stages

Variable

Lesion stage

Stage I

(mild)

Stage II

(moderate)

Stage III

(severe)

Age when put on CPAP (hrs.)

24 1.1

28.6 12.8

26.4 12.6

0.32NS

Age when injury developed (hrs.)

35.7 13.2

48.2 14.6

43.5 11.7

<0.001

Total duration on CPAP (hrs.)

50.0 14.7

96.4 32.5

137.3 36.3

<0.001

Figure1: Comparison of mean gestational age according to lesion stage

Figure 2: Comparison of mean birth weight according to lesion stage

DOI: 10.9790/0853-14114110116

www.iosrjournals.org

115 | Page

Continuouspositive Airway Pressure And Nasal Trauma In Neonates: A Descriptive Prospective

Figure 3: Comparison of mean duration on CPAP according to lesion stages.

DOI: 10.9790/0853-14114110116

www.iosrjournals.org

116 | Page

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1091)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- SFMA Score Sheet PDFДокумент7 страницSFMA Score Sheet PDFdgclarkeОценок пока нет

- 9 Major Benefits of Inner Sexual Alchemy AudioДокумент21 страница9 Major Benefits of Inner Sexual Alchemy AudioVasco GuerreiroОценок пока нет

- EvilHat DontReadThisBookДокумент200 страницEvilHat DontReadThisBookfabtinusОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Ophtha SIM 2nd EdДокумент250 страницOphtha SIM 2nd EdRalphОценок пока нет

- Cardiac OutputДокумент37 страницCardiac OutputIndrashish Chakravorty100% (1)

- Arnica The Miracle Remedy - Case RecordsДокумент4 страницыArnica The Miracle Remedy - Case Recordskaravi schiniasОценок пока нет

- VoacangaДокумент12 страницVoacangaLarry Selorm Amekuse100% (1)

- The Impact of Technologies On Society: A ReviewДокумент5 страницThe Impact of Technologies On Society: A ReviewInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)100% (1)

- Xerostomia Clinical Aspects and TreatmentДокумент14 страницXerostomia Clinical Aspects and TreatmentThanh Điền LưuОценок пока нет

- Peripheral Nerve InjuriesДокумент29 страницPeripheral Nerve InjuriesbrillniksОценок пока нет

- Orbital Trauma NCP and Drug StudyДокумент5 страницOrbital Trauma NCP and Drug StudyDersly LaneОценок пока нет

- Prisma Med - Schneider Electric - or SwitchboardДокумент20 страницPrisma Med - Schneider Electric - or SwitchboardAna RuxandraОценок пока нет

- Prof Ad 100Документ18 страницProf Ad 100Jennine Reyes100% (2)

- Attitude and Perceptions of University Students in Zimbabwe Towards HomosexualityДокумент5 страницAttitude and Perceptions of University Students in Zimbabwe Towards HomosexualityInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- "I Am Not Gay Says A Gay Christian." A Qualitative Study On Beliefs and Prejudices of Christians Towards Homosexuality in ZimbabweДокумент5 страниц"I Am Not Gay Says A Gay Christian." A Qualitative Study On Beliefs and Prejudices of Christians Towards Homosexuality in ZimbabweInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Socio-Ethical Impact of Turkish Dramas On Educated Females of Gujranwala-PakistanДокумент7 страницSocio-Ethical Impact of Turkish Dramas On Educated Females of Gujranwala-PakistanInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- The Role of Extrovert and Introvert Personality in Second Language AcquisitionДокумент6 страницThe Role of Extrovert and Introvert Personality in Second Language AcquisitionInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- A Review of Rural Local Government System in Zimbabwe From 1980 To 2014Документ15 страницA Review of Rural Local Government System in Zimbabwe From 1980 To 2014International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- A Proposed Framework On Working With Parents of Children With Special Needs in SingaporeДокумент7 страницA Proposed Framework On Working With Parents of Children With Special Needs in SingaporeInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Comparative Visual Analysis of Symbolic and Illegible Indus Valley Script With Other LanguagesДокумент7 страницComparative Visual Analysis of Symbolic and Illegible Indus Valley Script With Other LanguagesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Assessment of The Implementation of Federal Character in Nigeria.Документ5 страницAssessment of The Implementation of Federal Character in Nigeria.International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Investigation of Unbelief and Faith in The Islam According To The Statement, Mr. Ahmed MoftizadehДокумент4 страницыInvestigation of Unbelief and Faith in The Islam According To The Statement, Mr. Ahmed MoftizadehInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- An Evaluation of Lowell's Poem "The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket" As A Pastoral ElegyДокумент14 страницAn Evaluation of Lowell's Poem "The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket" As A Pastoral ElegyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Edward Albee and His Mother Characters: An Analysis of Selected PlaysДокумент5 страницEdward Albee and His Mother Characters: An Analysis of Selected PlaysInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Social Support and Self-Esteem of Adolescent GirlsДокумент5 страницRelationship Between Social Support and Self-Esteem of Adolescent GirlsInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Role of Madarsa Education in Empowerment of Muslims in IndiaДокумент6 страницRole of Madarsa Education in Empowerment of Muslims in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Designing of Indo-Western Garments Influenced From Different Indian Classical Dance CostumesДокумент5 страницDesigning of Indo-Western Garments Influenced From Different Indian Classical Dance CostumesIOSRjournalОценок пока нет

- Importance of Mass Media in Communicating Health Messages: An AnalysisДокумент6 страницImportance of Mass Media in Communicating Health Messages: An AnalysisInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- Topic: Using Wiki To Improve Students' Academic Writing in English Collaboratively: A Case Study On Undergraduate Students in BangladeshДокумент7 страницTopic: Using Wiki To Improve Students' Academic Writing in English Collaboratively: A Case Study On Undergraduate Students in BangladeshInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Оценок пока нет

- BTK AGUSTUS MutasiObatДокумент48 страницBTK AGUSTUS MutasiObatwulanwidya06Оценок пока нет

- Journal On Threpetical Study On MutraДокумент6 страницJournal On Threpetical Study On MutraVijay DawarОценок пока нет

- Patty NCP HyperthermiaДокумент4 страницыPatty NCP HyperthermiaPatricia Jean FaeldoneaОценок пока нет

- Rockaway TimesДокумент48 страницRockaway TimesPeter J. MahonОценок пока нет

- Shock Cheat Sheet PDFДокумент2 страницыShock Cheat Sheet PDFsarahjaimee100% (1)

- Consumos Medicamentos 2020Документ568 страницConsumos Medicamentos 2020LUCERO LOPEZОценок пока нет

- An Insight Into The Quality Assurance of Ayurvedic, Siddha and Unani DrugsДокумент10 страницAn Insight Into The Quality Assurance of Ayurvedic, Siddha and Unani DrugsHomoeopathic PulseОценок пока нет

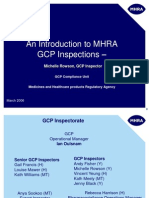

- An Introduction To MHRA GCP Inspections - : Michelle Rowson, GCP InspectorДокумент26 страницAn Introduction To MHRA GCP Inspections - : Michelle Rowson, GCP InspectorSwapnil PanpatilОценок пока нет

- Project Title: Lemon-Garlic Insect RepellentДокумент4 страницыProject Title: Lemon-Garlic Insect RepellentJayvie JavierОценок пока нет

- Pain After Laparoscopic CholecystectomyДокумент6 страницPain After Laparoscopic CholecystectomyMauro Hernandez CoutiñoОценок пока нет

- Housekeeping Check Lists-UpdatedДокумент26 страницHousekeeping Check Lists-UpdatedtanishaОценок пока нет

- RPOC and Homoeopathy - A Practical StudyДокумент4 страницыRPOC and Homoeopathy - A Practical StudyHomoeopathic Pulse100% (2)

- Red Blood Cell CountДокумент4 страницыRed Blood Cell CountMohamed MokhtarОценок пока нет

- Bmi Data May Joie J. AlcarazДокумент13 страницBmi Data May Joie J. AlcarazMay Joie JaymeОценок пока нет

- Current Views On Treatment of Vertigo and Dizziness (JURDING)Документ22 страницыCurrent Views On Treatment of Vertigo and Dizziness (JURDING)arifОценок пока нет

- Andrew Davies - Human Physiology - Ch08 Renal SystemДокумент85 страницAndrew Davies - Human Physiology - Ch08 Renal Systemapi-3814824Оценок пока нет

- HandoutДокумент3 страницыHandoutapi-336657051Оценок пока нет

- L & R PronunciationДокумент265 страницL & R PronunciationdooblahОценок пока нет