Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2013-Stewart-1541204013480369

Загружено:

Alina CiabucaИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice-2013-Stewart-1541204013480369

Загружено:

Alina CiabucaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Youth Violence and Juvenile

Justice

http://yvj.sagepub.com/

Youth Perceptions of the Police: Identifying Trajectories

Daniel M. Stewart, Robert G. Morris and Henriikka Weir

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice published online 1 April 2013

DOI: 10.1177/1541204013480369

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://yvj.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/03/08/1541204013480369

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences

Additional services and information for Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://yvj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://yvj.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> OnlineFirst Version of Record - Apr 1, 2013

What is This?

Downloaded from yvj.sagepub.com by alina ciabuca on October 20, 2013

Article

Youth Perceptions of the

Police: Identifying

Trajectories

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

00(0) 1-18

The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1541204013480369

yvj.sagepub.com

Daniel M. Stewart1, Robert G. Morris2, and Henriikka Weir3

Abstract

The relevance of examining juveniles attitudes toward the police has been firmly established in the

literature. Employing group-based trajectory modeling, the present study builds upon this previous

research by estimating police attitudinal trajectories among a general sample of youths. The models

produced a 5-group solution for both males and females, with four of the trajectories remaining

relatively stable over the time observed and one noticeably experiencing a downward trend.

Furthermore, of the items making up the police attitudinal scale, for several of the groups, the item

measuring prejudice most consistently oscillated away from the trajectory profile. Policy implications are discussed.

Keywords

youth, juveniles, attitudes, police

Maintaining a favorable image has been a prominent goal of the American police institution since its

public relations crisis of the 1960s and the subsequent emergence of the community policing movement, stressing positive collaborative relationships between the police and the citizenry to tackle

fear, crime, and disorder (Community Policing Consortium, 1994; Skolnick & Bayley, 1988; Walker

& Katz, 2011; Wycoff, 1988). It is theorized that a collaborative citizenry, one that is more likely to

assist the police in carrying out its core functions and serve as coproducers of protective services, is

also one that is more likely to hold favorable attitudes toward the police (Decker, 1981; Goldstein,

1987; Skolnick & Bayley, 1988; Wycoff, 1988). One group that increasingly consumes a substantial

amount of police time and resources (see Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI], 2011; Leiber, Nalla,

& Farnworth, 1998; Snyder & Sickmund, 1996; Truman, 2011; Walker & Katz, 2011) and, thus, is

an important target concerning the creation and maintenance of good public police relations is juveniles. Evidence even suggests that perceptions of legal actors, particularly police officers, can lead to

either compliance or rejection of legal and social norms among children and adolescents (Fagan &

1

University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA

University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA

3

University of Colorado Colorado Springs

2

Corresponding Author:

Daniel M. Stewart, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA.

Email: daniel.stewart@unt.edu

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 00(0)

Tyler, 2005). Being cognizant of juveniles perceptions of the police, then, has significant practical

implications, and it is why researchers and administrators over the last few decades have shown

considerable interest in the topic (see below).

The literature on juveniles perceptions of the police, though not as extensive as that of adults

perceptions, reveals that a cornucopia of factors affect attitudes, such as race, gender, delinquency,

and the nature of police contacts, just to name a few (Brick, Taylor, & Esbensen, 2009; Geistman &

Smith, 2007; Hinds, 2007; Hurst & Frank, 2000; Hurst, Frank, & Browning, 2000; Hurst, McDermott, & Thomas, 2005; Leiber et al., 1998; Sullivan, Dunham, & Alpert, 1987; Taylor, Turner,

Esbensen, & Winfree, 2001). Very little, however, has been written on juveniles attitudes toward

the police over time (Esbensen, Osgood, Taylor, Peterson, & Freng, 2001; Esbensen, Peterson,

Taylor, & Osgood, 2012; Piquero, Fagan, Mulvey, Steinberg, & Odgers, 2005), and only one study

exists that has identified and chronicled the changes in a longitudinal capacity across distinct

attitudinal developmental groups (Piquero et al., 2005)and even this work does not exclusively

focus on attitudes toward the police.

Here, we build upon existing literature by estimating trajectories of juveniles attitudes toward

the police using the longitudinal component of the National Evaluation of the Gang Resistance

Education and Training program (G.R.E.A.T. I; Esbensen et al., 2001). The current research, after

bifurcating subjects based on sex, attempts to identify and track the course of adolescents grouped

along attitudinal levels toward the police. It further seeks to examine the mean rates of the altitudinal

scales indicators about possible trajectory profiles. Its originality and value are rooted in this distinction since this approach has infrequently been applied to juvenile attitudes toward the police and,

thus, the identification of such attitudinal developmental groups requires further exploration. By

isolating the possible different attitudinal groups and following their course, while concurrently

examining mean rates of specific indicators, we will not only be adding to the knowledge base, creating a more complete understanding of juveniles attitudes toward the police but also be providing a

springboard for future research as well as for the creation of juvenile-focused police policies that can

take into account the nuances of attitudinal development.

Attitudes and Group-Based Trajectory Modeling

Longitudinal studies in which attitudes toward the police are presented as the primary variable of interest have almost exclusively focused on adults; therefore, the empirical reality concerning juveniles

attitudes toward the police over time is comparatively unknown. The adult-focused research, however,

shows that attitudes toward the police are relatively stable with prior attitudes serving as the best

predictors of subsequent attitudes (Brandl, Frank, Worden, & Bynum, 1994; Chermak, McGarrell,

& Weiss, 2001; Gau, 2010; Rosenbaum, Schuck, Costella, Hawkins, & Ring, 2005). In the only

longitudinal study examining juveniles perceptions that has employed a similar methodology as the

one used here, it was also revealed that attitudes concerning legitimacy of law changed very little over

time (Piquero et al., 2005). These findings correspond with the various conceptions of attitudes, which

have referred to their enduring natures or settled dispositions as well as with the characterizations of

attitudes as traits with fairly permanent qualities (see Eagly & Chaiken, 1993).

Attitudes are not entirely immutable, though. Among adult populations, while not as powerful as

preexisting notions, evidence holds personal experiences play a role in attitudinal variability. For

instance, research by Gau (2010) examining respondents perceptions of police officers ability to

prevent crime revealed that, even when controlling for prior attitudes, perceptions of police contact

quality and being subjected to an unjustified stop were significant predictors. Brandl et al. (1994),

after taking into consideration prior global satisfaction, found that global attitudes of the police were

influenced by assessments of police assistance and information contacts. Even in the aforementioned

Piquero et al. (2005) research, a group of juveniles was identified whose legitimacy perceptions

Stewart et al.

dramatically increased during the period under study. Furthermore, research holds that adults hold

more favorable attitudes toward the police than juveniles (Apple & OBrien, 1983; Boggs & Galliher, 1975; Scaglion & Condon, 1980; Smith & Hawkins, 1973), evidence that over time those attitudes are indeed changing, becoming increasingly positive. In sum, though the parameters of

attitudinal ranges might be limited once formulated, evidence shows there is still room for

changeeven if it is merely a slight oscillation away from the mean.

A portion of the attitudinal stability that is observed, however, is undoubtedly a product of the

multitude of factors behind perceptions combined with limitations of the methodologies and statistical analyses employed when measuring the development of attitudes. Without providing an

exhaustive discussion of construct validity and the difficulties related to measuring change, it

should simply be noted that attitudes in general can be conceived as being the products of a complex set of factors such as beliefs, feelings, and past behaviors (see Maio, Esses, Arnold, & Olson,

2004; Zanna & Rempel, 1988), impacting individuals over a protracted period and most likely

beyond the time frame of empirical observation. By employing group-based trajectory (GBT)

modeling (aka finite mixture modeling) and utilizing a panel study design in which juveniles

attitudes toward the police are examined over a 5-year period as we do here, we can more closely

inspect the issue of attitudinal stability and increase the likelihood of capturing meaningful change

as it occurs.

It is important to note that GBT modeling has become commonplace within the criminological

literature surrounding life course transitions and behavioral development. Nagin and Land (1993)

originally popularized the technique as a means of investigating processes evolving over time or age

by isolating individuals into finite developmental groups or trajectories. While other popular

schemes used to analyze longitudinal data, such as hierarchal linear modeling (i.e., growth curve

models), assume a continuous, normal distribution of trajectories in the population, GBT modeling

makes no such parametric assumptions; rather it stresses the possibility of a limited number of

clustersgroups within the distribution that are distinguishable by similar developmental trajectories. Further, whereas standard growth curve models describe the average probability trajectory

of some development process as well as the individual variability about the mean trajectory (with

the ultimate goal entailing the identification of factors explaining such variability), GBT modeling

focuses on assigning cases to latent classes to which they have the highest probability of belonging

and subsequently identifying factors distinguishing group membership in addition to factors impacting the intercepts and slopes of development within each particular latent class (Nagin, 2005; Nagin

& Piquero, 2010). This technique has been used to explain the development of criminality across

varying stages of the life course (e.g., Bushway, Piquero, Broidy, Cauffman, & Mazzerolle,

2001; Hay & Forrest, 2006; Laub, Nagin, & Sampson, 1998; Morris, Carriaga, Diamond, Piquero,

& Piquero, 2012; Morris & Piquero, 2012; Sampson & Laub, 1993) but has rarely been used to

explore attitudes toward the police (discussed further below).

The group-based approach to juvenile attitudes toward the police is appropriate since it is

reasonable to assume that not all juvenile attitudes follow a common increasing or decreasing developmental patterncounter to processes that lend themselves more to standard growth curve models

(see Raudenbush, 2001; Warr, 2002). As mentioned previously, demographics and experiential

factors account for much of the variance surrounding favorable or unfavorable evaluations of particular issues. It makes sense then to assume that some youths will always have highly positive views

of the police, others will never hold the police in such regard, and some will develop an increasingly

positive view toward police, and for others initially positive attitudes will deteriorate (i.e., become

negative) over time. Furthermore, it is reasonable to believe that the mean rates of certain items

comprising the attitudinal scale, while consistent enough to belong to particular groups, will noticeably depart from the trajectory. The goal of this exploratory article is to identify those unique groupings and their developmental patterns.

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 00(0)

Though Piquero et al. (2005) were the first and, to the current authors knowledge, only researchers to have taken a similar methodological/statistical approach when examining juveniles attitudes

toward the police, the current research is different in a variety of ways. First, the attitudinal measures

used here exclusively pertain to the police; that is, in Piquero et al., the legitimacy scale, which was

one of their primary variables of interest, measured respondents in terms of their perceptions about

judges and the courts as well the police. Second, we observe five points of data collected annually

over a 5-year period, whereas Piquero et al. examined four repeated observations spanning only 18

months. Third, we examine a younger sample of youths, with all participants at the first wave of data

collection being 12 years of age. The average baseline age in the work of Piquero et al. was 16.04

(range 1418). And finally, although Piquero et al. examined a sample of serious adolescent offenders from two cities, here we study a more general sample of juveniles across six U.S. cities. Other

differences exist as well, but the point being illustrated here is that the current research makes a

unique and significant contribution to the literature by determining whether developmental patterns

concerning attitudes toward the police exist among a general sample of juveniles. Moreover, if

different patterns emerge, we seek to determine whether they remain stable or experience marked

change over the time observed. Finally, contingent upon the presence of discrete patterns, the current

research will analyze the variability of the items mean rates, making up the specific profiles.

Data and Method

Data

Data for the present study were culled from the longitudinal component of the G.R.E.A.T. program

(see Esbensen et al., 2001). These data provide a multi-item police attitudes scale, which is consistent across five annual waves of data collection, making them ideal for assessing attitudinal

development. The G.R.E.A.T. data were originally collected from students attending 22 middle

schools from within six U.S. cities. The original sample consisted of over 3,500 students of which

parental consent was obtained from 2,045 (57%). The original research team surveyed these students

annually from 1995 (sixth and seventh grade) through 1999. We limited our analysis to youth who

were 12 years old at Wave 1, who participated completely through the fifth wave, and who reported

to at least 4 of the 7 items regarding attitudes toward policediscussed below (n 927).

We further stratified the sample by gender in order to tease out such differences in attitudinal

development. Although gender differences in relation to police attitudes have not been conclusively

established in the literature, with one study reporting higher police perceptions among adolescent

males than females (Hurst & Frank, 2000) and others finding gender to be a relative nonfactor (Brick

et al., 2009; Chow, 2011; Griffiths & Winfree, 1982; Moretz, 1980; Winfree & Griffiths, 1977),

several pieces of research have shown gender to be directly or indirectly related to attitudes toward

the police, with adolescent females reporting more favorable perceptions of the police than males

(Bouma, 1969; Brandt & Markus, 2000; Geistman & Smith, 2007; Hurst, Frank, & Browning,

2000; Portune, 1971; Taylor, Turner, Esbensen, & Winfree, 2001). And while it is largely maintained that cultural expectations and norms produce much of the general behavioral differences

observed in males and females (Feingold, 1992; Grossman & Grossman, 1994), differentiation

between the sexes is nonetheless extant and warrants examination in this context. Moreover, this

distinction is not lost on the juvenile justice system, which in recent years has increasingly invested

in gender-specific delinquency programs (see Foley, 2008). Our sample consisted of 421 (45%)

males and 506 (55%) females.

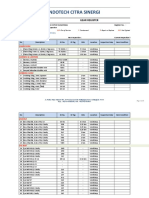

Descriptive statistics for the youth represented in our analyses are presented in Table 1. After

partitioning the sample based on sex, we opted to include descriptive statistics on variables the literature has found to be relevant to attitudes toward the police, such as race, perceptions of safety,

Stewart et al.

Table 1. Sample Demographics by Gender.

Male

White

Black

Hispanic

Other

School environment

Delinquency

Victimization

Gang membershipa

Arrestsb

n

Female

SD

SD

0.60

0.12

0.20

0.08

2.77

19.61

5.46

0.05

0.26

421

0.49

0.33

0.40

0.28

0.27

58.81

22.92

0.21

0.92

0.55

0.14

0.19

0.12

2.72

6.68

3.11

0.03

0.07

506

0.50

0.35

0.39

0.32

0.26

19.46

15.72

0.16

0.37

Variable indicating gang membership was missing some observations (n 342 for males; n 424 for females). b Number of

arrests reported for 6 months prior to interview truncated to 10 arrests, which was generally at the 99th percentile. Number

of arrests was not collected in Waves 1 and 2.

victimization, delinquency, and arrests (Brick, Taylor, & Esbensen, 2009; Brown & Coulter, 1983;

Dean, 1980; Frank, Brandl, Cullen, & Stichman, 1996; Geistman & Smith, 2007; Homant, Kennedy,

& Fleming, 1984; Hurst & Frank, 2000; Hurst et al., 2000, 2005; Koenig, 1980; Leiber et al., 1998;

Sullivan et al., 1987; Taylor et al., 2001). As shown in Table 1, the majority of the sample for both

sexes is White (60% of males and 55% of females). And while perceptions of school safety appear to

be similar between the two groups, males report on average 3 times as many incidents of

delinquency than females. Victimization, gang membership, and number of arrests appear to be

more frequent among males than among females (see scale items).

Measurement

The G.R.E.A.T. data are rich in measures and of focus here are a series of indicators measuring

attitudes toward police. Using a 5-point Likert-type scale, respondents were asked about their level

of agreement, with higher scores indicating higher levels of agreement (i.e., more positive), to the

following statements: police officers are honest, most police officers are usually rude (reverse

coded), police officers are hardworking, most police officers are usually friendly, police

officers are usually courteous, police officers are respectful toward people like me, and

police officers are prejudiced against minority persons (reverse coded). Responses to these questions were then averaged to represent overall attitude toward police at each wave. Internal consistency

for the attitude scale was strong at each wave (a coefficients were .84, .86, .88, .87, and .89 at Waves 1

through 5). For cases missing only one wave worth of data for a given scale item, data were imputed by

taking the average response from the previous and next report when the datum was missing at Waves

2, 3, or 4, respectively. A missing datum on Wave 1 was imputed with the Wave 2 report to the same

item, and a missing datum at Wave 5 was imputed with that which was reported at Wave 4.

Analytical Procedure

This study assessed the development of attitudes toward police among high-risk youth from age 12

to age 16, relying on GBT modeling (aka finite mixture modeling). Our GBT analysis was carried

out in a series of steps that directly account for the nested nature of the data (i.e., repeated observations over time are nested within an individual). The first stage of the analysis involved

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 00(0)

approximating a longitudinal latent class analysis (LLCA), which is one form of GBT modeling

(Nagin & Land, 1993). The mathematical underpinnings of this analytical technique are covered

in more detail elsewhere (see Feldman, Masyn, & Conger, 2009). LLCA systematically classifies

the observed attitude trajectories into one group among a user-specified number of group of trajectories. It is important to note that unlike other GBTs, LLCA assumes no functional form of the

trajectory (e.g., linear, quadratic, etc.) but classifies individuals based on patterns of development.

We relied on contemporary standards for determining the final number of groups to retain, which is

the focus of the findings section presented below.

Results

Trajectory Analysis

In this study, trajectory analysis was used to model the development of attitudes toward police for a

5-year period among high-risk youth from ages 12 through 16. One of the benefits of LLCA

approach is that it does not presume any specific time function or proportional odds. Therefore,

complicated models of change can be evaluated without violating assumptions that some other

techniques may impose (Feldman et al., 2009).

The first stage of a trajectory analysis involves the decision about the appropriate number of

classes to retain in a final solution. This is usually done by using unconditional trajectory models,

which are models without covariates (see Nylund & Masyn, 2008). Model selection is typically

based on the evaluation of comparative fit indices. The final solution was based on the evaluation

of Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) statistics, posterior probabilities, class proportions,

graphically visualized mean trajectories for each class, and parsimony. Tables 2 and 3 present the

fit statistics of the 2-group, 3-group, 4-group, 5-group, and 6-group LLCA results for males and

females, respectively.

Based on a preponderance of the evidence, the 5-group model was determined as the most appropriate in representing the development of attitudes toward police from age 12 to age 16 for both

males and females, respectively. Although the 6-group solutions resulted in improved BIC, posterior

probabilities were weakened as were proportions for males. Considering this along with model

parsimony, we decided upon the 5-group solution. Based on this solution, these distinct attitudinaldevelopmental trajectory profiles were labeled as low-stable, midrange-stable, upper

mid-stable, high-stable, and midrange declining. Figures 1 and 2 display the trajectory profiles for

the five-class solutions retained, again for each gender.

Heterogeneity in Attitudes Toward the Police

The male and female trajectory profiles share several characteristics, with attitudes toward the police

tending to be stable for most youth, although at varying degrees of positivity.

Each gender is predominantly represented by individuals who have midrange (26.6% for males;

38.7% for females) or upper midrange (38.5% for males; 36.4% for females) attitudes toward police,

which tend to remain stable from 12 to 16 years of age. Both genders are also represented by a group

of juveniles who report very high attitudes toward police (10.4% of males; 8.5% of females), also

remaining stable. On the opposite end of the spectrum, there are groups of juveniles who tend to

report negative attitudes toward police (9.3% of males; 10.0% of females) across the full observation

period, and these youths attitudes tend to be relatively stable. Perhaps more interesting is that one of

the five groups, for both males and females, the midrange declining group (15.2% of males; 5.5% of

females), reports mid to mid-upper level attitudes toward police; but at about age 13, their attitudes

begin to deteriorate; and by age 16, these youth have the lowest attitudes toward police. Unlike their

more stable counterparts, the midrange decliners are considerably different with regard to

Stewart et al.

Table 2. Longitudinal Latent Class Analysis Results for Males.

BIC

Group 2

4,730.581

Group 3

4,538.843

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Prob.

%

Class 1

0.930

Class 2

0.949

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Class 1

0.935

Class 2

0.921

Class 3

0.921

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Class 1

0.889

Class 2

0.934

Class 3

0.890

Class 4

0.937

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Class 1

0.943

Class 2

0.823

Class 3

0.816

Class 4

0.938

Class 5

0.883

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Class 1

0.935

Class 2

0.865

Class 3

0.762

Class 4

0.833

Class 5

0.956

Class 6

0.847

Group 4

4,468.967

Group 5

4,439.928

Group 6

4,420.043

2-group model

#

3-group

4-group

5-group

6-group

50.4

49.6

model

11.9

50.1

38.0

model

38.9

10.7

39.7

10.7

model

9.3

15.2

26.6

10.4

38.5

model

9.7

33.7

7.6

13.1

9.5

26.4

212

209

50

211

160

164

45

167

45

39

64

112

44

162

41

142

32

55

40

111

Note. BIC Bayesian Information Criterion.

proportional representation between genders. Proportionally speaking, we found 2.76 times more

males in this group than females.

In sum, nearly half of males (48.9%) and more than half of females (53.4%) tend to have rather

positive outlooks toward the police, and these attitudes tend to remain stable from 12 to 16. A sizable

proportion of both genders have midrange attitudes that remain stable and a smaller group has poor

attitudes, both of which tend to remain across time. However, some youth tend to have positive

attitudes until about age 13, but then their attitudes decline rapidly through age 16. In the end, these

findings show that there is in fact considerable heterogeneity in the development of attitudes toward

the police. Most youths attitudes are consistent during this time period (i.e., they remain high if they

start high, low if they start low, etc.) though other youth tend to report degenerative attitudes about

the police as time goes on.

In an effort to extend the exploration further, we also plotted the mean levels for each specific

item underlying the attitude scale at each wave along with the estimated trajectory profile (see

Figure 2). This was done for both males and females separately. These findings suggest that for most

trajectory groups, the mean rates of specific attitude indicators fall consistently within the trajectory

profile; however, in some cases, 1 or more items tend to fall outside of the overall pattern. For example, in the low-stable male group (notated as Group 1 in Figure 2), which is the group whose

members hold the least favorable attitudes toward the police, members tend to maintain comparatively better attitudes about the police regarding the idea that the police are prejudiced toward

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 00(0)

Table 3. Longitudinal Latent Class Analysis Results for Females.

BIC

Group 2

4,964.064

Group 3

4,720.257

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Prob.

%

Class 1

0.911

Class 2

0.939

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Class 1

0.931

Class 2

0.910

Class 3

0.875

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Class 1

0.895

Class 2

0.870

Class 3

0.892

Class 4

0.862

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Class 1

0.929

Class 2

0.863

Class 3

0.839

Class 4

0.887

Class 5

0.883

Posterior probabilities and class proportions for

Class 1

0.899

Class 2

0.909

Class 3

0.858

Class 4

0.864

Class 5

0.839

Class 6

0.906

Group 4

4,645.168

Group 5

4,609.971

Group 6

4,581.032

2-group model

#

3-group

4-group

5-group

6-group

46.4

53.6

model

16.2

55.5

28.3

model

9.9

41.5

38.7

9.9

model

10.9

5.5

38.7

8.5

36.4

model

1.2

13.8

36.8

34.6

6.1

7.5

235

271

82

281

143

50

210

196

50

55

28

196

43

184

6

70

186

175

31

38

Note. BIC Bayesian Information Criterion.

minorities. Males in the high-stable group (those with the most positive attitudes toward police) are

fairly consistent across items; however, it is interesting that the prejudice item is clearly the lowest

ranking item. In other words, these youth have positive attitudes toward the police, but the aspect

about the police that generates the most negativity has to do with prejudice.

For females in the low-stable group, respondents had comparatively more agreement with the

statement about police being hardworking. And somewhat similar to that of males, as the same group

members got older, their perceptions of police prejudice improved as well; that is, they increasingly

viewed the police as less prejudiced. Also like their male counterparts, the two female groups with

the most positive attitudes toward the police consistently ranked the police prejudice item lower than

other attitudinal items (Figures 2 and 3).

Discussion and Conclusion

The emphasis on gauging public perceptions of the police sprouted from movements aimed at

improving relationships between the police and the community. Juveniles have long been a segment

of the community that experiences frequent encounters with the policeand because of the discretionary nature of policing, in many cases police officers are the only agents of the criminal justice

system with whom juveniles come into contact (Caldwell & Black, 1971; Cavan & Ferdinand,

1975). Consequently, these contacts can be extremely valuable in forming the basis for future

Stewart et al.

Females

Development of Attitudes Toward Police (Ages 12-16, n=506)

12

13

14

Age

Class 1, 10.%

Class 3, 38.7%

Class 5, 36.4%

15

16

Class 2, 5.5%

Class 4, 8.5%

Males

Development of Attitudes Toward Police (Ages 12-16, n=421)

12

13

14

Age

Class 1, 9.3%

Class 3, 26.6%

Class 5, 38.5%

15

16

Class 2, 15.2%

Class 4, 10.4%

Figure 1. Trajectories of attitudes toward police: males and females.

policecommunity relations (Winfree & Griffiths, 1977). The importance of maintaining a positive

police image in the eyes of juveniles as well as studying juveniles attitudes toward the police then

cannot be overstated.

While previous research has mostly examined juveniles perceptions of law enforcement in crosssectional capacities, this study adds to the scant literature devoted to examining juveniles attitudes

10

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 00(0)

of the police over time. Using the LLCA approach to GBT modeling, a 5-group model was retained

from data produced by the national evaluation of G.R.E.A.T. for both males and females. The results

revealed that most respondents held relatively favorable attitudes toward the police, with four of the

groups from each gender remaining relatively stable over the time observed. That is, those juveniles

that started off with high baseline attitudes also ended the period of observation with high attitudes.

The findings of relative stability correspond to those in the police attitudinal literature concerning

adults, with most longitudinal designs focusing on adults attitudes toward the police demonstrating

a comparative degree of constancy over time (Brandl et al., 1994; Chermak et al., 2001; Gau, 2010;

Rosenbaum et al., 2005). The degree of stability and number of groups retained was also similar to

the findings of Piquero et al. (2005) wherein they retained five groups when examining individuals

perceptions of legitimacy of law. But unlike these studies, we employed GBT modeling and identified unique attitudinal groupings among a general sample of juveniles, allowing us for the first time

to conclude based on empirical evidence that not all juvenile attitudes exclusively pertaining to the

police follow a common increasing or decreasing trajectory.

Although extending well beyond the scope of the G.R.E.A.T. I data, future projects could entail

panel studies wherein participants are followed into adulthood. Such an approach would provide a

more holistic picture of attitudinal development and one wherein specific shifts in trajectories could

be identified that possibly comport with significant life events. For instance, the extant literature

demonstrates that juveniles hold the police in lower regard than adults (Apple & OBrien, 1983;

Boggs & Galliher, 1975; Scaglion & Condon, 1980; Smith & Hawkins, 1973) and that even younger

adults have less favorable attitudes about the police than older adults (Murphy & Worrall, 1999;

Nofziger & Williams, 2005; Schafer, Huebner, & Bynum, 2003; Weitzer & Tuch, 2002). By extending the time period under study, researchers might be able to identify when and how the trajectories

begin their lasting upward trends. Perhaps groups differ in response to graduating college, obtaining

career employment, getting married, or having children. The period of observation in the current

study only surveys juveniles from the ages 12 to 16.

Our finding that males held the police in lower regard than females do, albeit slightly, comports

with the bulk of the literature showing more positive attitudes toward the police among females than

males (Bouma, 1969; Brandt & Markus, 2000; Geistman & Smith, 2007; Hurst et al., 2000; Portune,

1971; Taylor et al., 2001). Further, the mid-declining group (Group 2), the group from each sex that

started at a moderate level but dropped precipitously at around age 13, contained a greater percentage of males (15.2%) than females (5.5%). Such disparities in attitudes between the sexes are often

explained by the nature of police contacts, with positive contacts (i.e., assistance, providing information, etc.) producing positive perceptions of the police and negative contacts (i.e., invocation

of social control) detrimentally impacting attitudes toward the police (Brown & Benedict, 2002;

Smith, Graham, & Adams, 1991; Worrall, 1999). A specific type of contact that produces negative

sentiments, among juveniles as well as adults, is arrest (Brick et al., 2009; Smith & Hawkins, 1973);

and since males make up over two thirds of juvenile arrests (Puzzanchera & Adams, 2011; Snyder,

2008), the differential in male and female attitudes found here is not too surprising. In fact, male

respondents in the current sample reported more arrests on average than females. Further, it could

be that the members of the low-stable and mid-declining group for both sexes experienced a greater

incidence and/or frequency of arrests than members of other groups.

Delinquency is another factor that could be producing the modest variance in attitudes toward

police between the sexes. Males consistently report more delinquent acts than females (Canter,

1982; Sampson, 1985; Snyder & Sickmund, 2006; White & LaGrange, 1987), as they did here in

the current samplea possible indicator, along with arrests, of adhering to subcultures with distinguishable values that stress hostility toward authority figures (see Anderson, 1999; Cohen, 1955;

Cloward & Ohlin, 1960; Miller, 1958). Brick et al. (2009) found that, after controlling for serious

delinquency, initial differences between the sexes concerning attitudes toward the police

Stewart et al.

11

Figure 2. Group attitude trajectory by specific question: males.

disappeared. Although the current study exclusively focuses on identifying trajectories and describing them in terms of the sole demographic of sex, our future research aims at identifying other factors that distinguish group membership, giving particular attention to arrests, delinquency,

victimization, and race. All of which, in cross-sectional studies, have been shown to affect juveniles

attitudes toward the police (Brick et al., 2009; Geistman & Smith, 2007; Hurst & Frank, 2000; Hurst

et al., 2000, 2005; Leiber et al., 1998; Sullivan et al., 1987; Taylor et al., 2001).

The discovery of the mid-declining group is noteworthy because its trajectory illustrates a particular point in time wherein attitudes significantly shift downwardbetween the ages of 12 and 13. In

fact, among females, members of this group held the lowest perceptions of the policeeventually

12

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 00(0)

Figure 3. Group attitude trajectory by specific question: females.

dipping below the low- and middle-stable groups. Regardless of the particular factors behind this

descending trend, an important implication of this finding is the necessity for early intervention. And

since the literature demonstrates a relationship between delinquency and attitudes toward the police

(Brick et al., 2009; Cox & Falkenberg, 1987; Leiber et al., 1998), predelinquent intervention

programs already in place could be utilized to shore up attitudes toward the police with the value

addition of producing a more collaborative citizen in adulthood. Practitioners looking for solutions

to poor policejuvenile relations, then, would do well to research to the numerous promising intervention programs identified by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention currently

carried out in schools and communities (Loeber, Farrington, & Petechuk, 2003). These programs,

Stewart et al.

13

which entail a variety of curricula such as classroom and behavior management, conflict resolution

and violence prevention, anti-bullying directives, mentoring, and afterschool recreation, can be

adapted to include instruction conducive to prosocial attitudes toward the police. Police Athletic

Leagues, which have chapters all across the country, already incorporate such practices in their

programming, with one of their goals being developing strong positive attitudes toward the police

(National Association of Police Athletic/Activities Leagues, Inc., 2013). The G.R.E.A.T. program,

whose evaluation provided the data used here, is another such program that focuses on prevention.

Its antigang and delinquency message is delivered in schools directly by school resource officers and

police officers, with the aim of developing positive relations with law enforcement. Cross-sectional

as well as longitudinal evaluations of the program have suggested that many participants end up having more positive attitudes toward the police than nonparticipants (Esbensen & Osgood, 1999;

Esbensen et al., 2001; Esbensen, Peterson, Taylor, & Osgood, 2012). Finally, an evaluation of the

Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) program, from which G.R.E.A.T. was loosely

modeled, revealed that police officers who provided the instruction received better evaluations than

nonpolice officer instructors (Hammond et al., 2008).

The discovery of visible differentials between individual items making up the attitudinal scale

is important, as wellparticularly the finding concerning the prejudice item. Recall that, although

the members making up the groups with the most positive attitudes toward the police (Groups 4

and 5) consistently rated the police on all attitudinal items higher than members of the groups with

the worst attitudes of the police, in relation to the mean scores on other items within the group, the

item measuring prejudice among Groups 4 and 5 was consistently the lowest, for both sexes (with

lower scores indicating higher perceptions of police prejudice). The opposite was true for the

groups with the least favorable attitudes toward the police, however (i.e., those group members

consistently rated the police less prejudiced in relation to other itemsGroups 1 and 2 for males).

This seemingly perplexing finding could be due to police contact, with members of higher attitudinal groups possibly having little contact with the police and basing their perceptions on external

sources as to how the police typically interact with monitories. The groups with lower attitudes,

though, possibly because their members have experienced a greater degree of police contact and

thus are more directly knowledgeable of the reality of police officer behavior, might be contending

that, even though they are comparatively dissatisfied with the police, the police are not racially

biased in the commission of their dutiesparticularly in relation to other officer behaviors.

Research does show that aspects of citizen demeanor are better indicators of police behavior

toward citizens than race and class (Black, 1971; Mastrofski, Reisig, & McCluskey, 2002; Piliavin

& Briar, 1964). Regardless of the reason, these particular findings have implications for the field

of procedural justice. The theory of procedural justice maintains that public perceptions of fairness

of the criminal justice system and respect for the law are inextricably intertwined with perceived

legitimacy and, ultimately, willingness to comply with the law (Tyler, 1990, 2007; Tyler & Huo,

2002). Believing that the police are prejudiced, then, more than likely, compromises conceptions

of fairness and respect, increasing the chances of delinquency. When attempting to build police

youth relationships, police officials should pay particular attention to youths notions of racial

discrimination.

As with any social scientific endeavor, replication is necessary to ensure a more complete understanding of the phenomena under study as well as prior to committing to any consequential public

policy. For example, it is important to discover whether these trajectories would emerge using other

populations. Nonetheless, administrators should look to the aforementioned intervention programs

as viable options for developing cordial relationships between the police and juveniles that can continue into adulthood. With the identification of different developmental trajectories, however, it is

evident that a one-size-fits-all approach might be ineffective. In future research, it is our intention

to identify factors determining group membership as well as factors associated with developmental

14

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 00(0)

patterns themselves. The current study, then, can be viewed as a first step in understanding how juveniles attitudes toward the police develop as they age.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

References

Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York, NY:

W. W. Norton.

Apple, N., & OBrien, D. (1983). Neighborhood racial composition and residents evaluation of police performance. American Sociological Review, 11, 7684.

Black, D. (1971). The social organization of arrest. Stanford Law Review, 23, 10871111.

Boggs, S. L., & Galliher, S. F. (1975). Evaluating the police: A comparison of black street and household

respondents. Social Problems, 13, 393406.

Bouma, D. H. (1969). Kids and cops. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans.

Brandl, S. G., Frank, J., Worden, R. E., & Bynum, T. S. (1994). Global and specific attitudes toward the police:

Disentangling the relationship. Justice Quarterly, 11, 119134.

Brandt, D. E., & Markus, K. A. (2000). Adolescent attitudes towards the police: A new generation. Journal of

Police and Criminal Psychology, 15, 1016.

Brick, B. T., Taylor, T. J., & Esbensen, F.-A. (2009). Juvenile attitudes towards the police: The importance of

subcultural involvement and community ties. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37, 488495.

Brown, B., & Benedict, W. R. (2002). Perceptions of the police: Past findings, methodological issues, conceptual issues and policy implications. Policing, 25, 543580.

Brown, K., & Coulter, P. (1983). Subjective and objective measures of police service delivery. Public

Administration Review, 43, 5058.

Bushway, S. D., Piquero, A. R., Broidy, L. M., Cauffman, E., & Mazerolle, P. (2001). An empirical framework

for studying desistance as a process. Criminology, 39, 491515.

Caldwell, R. G., & Black, J. A. (1971). Juvenile delinquency. New York, NY: Ronald Press.

Canter, R. J. (1982). Sex differences in self-report delinquency. Criminology, 20, 373394.

Cavan, R. C., & Ferdinand, T. N. (1975). Juvenile delinquency. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott.

Chermak, S., McGarrell, E. F., & Weiss, A. (2001). Citizens perceptions of aggressive traffic enforcement

strategies. Justice Quarterly, 18, 365391.

Chow, H. P. H. (2011). Adolescent attitudes toward the police in a western Canadian city. Policing, 34,

638653.

Cloward, R. A., & Ohlin, L. E. (1960). Delinquency and opportunity: A theory of delinquent gangs. New York,

NY: Free Press.

Cohen, A. K. (1955). Delinquent boys: The culture of the gang. New York, NY: Free Press.

Community Policing Consortium. (1994). Understanding community policing: A framework for action.

Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Cox, T. C., & Falkenberg, S. D. (1987). Adolescents attitudes toward the police: An emphasis on interactions

between the delinquency measures of alcohol and marijuana, police contacts and attitudes. American

Journal of Police, 6, 4562.

Dean, D. (1980). Citizen ratings of the police: The difference police contact makes. Law and Policy Quarterly,

2, 445471.

Stewart et al.

15

Decker, S. (1981) Citizen attitudes toward the police. A review of past findings and suggestions for future

police. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 9, 8087.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich,

Inc.

Esbensen, F.-A., & Osgood, D. W. (1999). Gang resistance education and training (GREAT): Results from the

national evaluation. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 36, 194225.

Esbensen, F.-A., Osgood, D. W., Taylor, T. J., Peterson, D., & Freng, A. (2001). How great is G.R.E.A.T?

Results from a longitudinal quasi-experimental design. Criminology & Public Policy, 1, 87118.

Esbensen, F.-A., Peterson, D., Taylor, T. J., & Osgood, D. W. (2012). Results from a multi-site evaluation of the

G.R.E.A.T. program. Justice Quarterly, 29, 125151.

Fagan, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2005). Legal socialization of children and adolescents. Social Justice Research, 18,

217242.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2011). Ten-year arrest trends. Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/

cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2010/crime-in-the-u.s.-2010/tables/10tbl32.xls

Feingold, A. (1992). Sex differences in variability in intellectual abilities: A new look at an old controversy.

Review of Educational Research, 62, 6184.

Feldman, B. J., Masyn, K. E., & Conger, R. D. (2009). New approaches to studying problem behaviors: A

comparison of methods for modeling longitudinal, categorical adolescent drinking data. Developmental

Psychology, 43, 652676.

Foley, A. (2008). The current state of gender-specific delinquency programming. Journal of Criminal Justice,

36, 262269.

Frank, J., Brandl, S., Cullen, F. T., & Stichman, A. (1996). Reassessing the impact of race on citizens attitudes

toward the police: A research note. Justice Quarterly, 13, 321334.

Gau, J. M. (2010). A longitudinal analysis of citizens attitudes about police. Policing, 33, 236252.

Geistman, J., & Smith, B. W. (2007). Juvenile attitudes toward police: A national study. Journal of Crime and

Justice, 30, 2751.

Goldstein, H. (1987). Toward community-oriented policing: Potential, basic requirements, and threshold

questions. Crime & Delinquency, 33, 610.

Griffiths, C. T., & Winfree, L. T. (1982). Attitudes toward the police: A comparison of Canadian and American

adolescents. Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 6, 128141.

Grossman, H., & Grossman, S. H. (1994). Gender issues in education. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Hammond, A., Sloboda, Z., Tonkin, P., Stephens, R., Teasdale, B., Grey, S. F., & Williams, J. (2008). Do

adolescents perceive police officers as credible instructors of substance abuse prevention programs? Health

Education Research, 23, 682696.

Hay, C., & Forrest, W. (2006). The development of self-control: Examining self-control theorys stability

thesis. Criminology, 44, 739774.

Hinds, L. (2007). Building police-youth relationships: The importance of procedural justice. Youth Justice, 7,

195209.

Homant, R., Kennedy, D., & Flemming, R. (1984). The effect of victimization and the police response on

citizens attitudes toward police. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 12, 323332.

Hurst, Y. G., & Frank, J. (2000). How kids view cops: The nature of juvenile attitudes toward the police.

Journal of Criminal Justice, 28, 189202.

Hurst, Y. G., Frank, J., & Browning, S. L. (2000). The attitudes of juveniles toward the police. Policing, 23, 3753.

Hurst, Y. G., McDermott, M. J., & Thomas, D. L. (2005). The attitudes of girls toward the police: Differences

by race. Policing, 28, 578593.

Koenig, D. J. (1980). The effect of crime victimization and judicial or police contacts on public attitudes toward

the local police. Journal of Police Science & Administration, 8, 243249.

Laub, J. H., Nagin, D. S., & Sampson, R. J. (1998). Trajectories of change in criminal offending: Good

marriages and the desistance process. American Sociological Review, 63, 225238.

16

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 00(0)

Leiber, M. J., Nalla, M. K., & Farnworth, M. (1998). Explaining juveniles attitudes toward the police. Justice

Quarterly, 15, 151174.

Loeber, R., Farrington, D. P., & Petechuk, D. (2003). Child delinquency: Early intervention and prevention.

Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Maio, G. R., Esses, V. M., Arnold, K. H., & Olson, J. M. (2004). The function-structure model of attitudes:

Incorporating the need for affect. In G. Haddock & G. R. Maio (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on the

psychology of attitudes (pp. 933). Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

Mastrofski, S., Reisig, M., & McCluskey, J. (2002). Police disrespect toward the public: An encounter-based

analysis. Criminology, 40, 519551.

Miller, J. (1958). Lower-class culture as generating milieu of gang delinquency. Journal of Social Issues, 14,

519.

Moretz, W. (1980). Kids to cops: We think youre important, but were not sure we understand you. Journal of

Police Science and Administration, 8, 220224.

Morris, R. G., Carriaga, M. L., Diamond, B., Leeper-Piquero, N., & Piquero, A. R. (2012). Does prison strain

lead to prison misconduct? An application of general strain theory. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40,

194201.

Morris, R. G., & Piquero, A. R. (2012). For whom do sanctions deter and label? Justice Quarterly. doi:10.1080/

07418825.2011.633543

Murphy, D. W., & Worrall, J. L. (1999). Residency requirements and public perceptions of the police in large

municipalities. Policing, 22, 327342.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling and development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nagin, D. S., & Land, K. C. (1993). Age, criminal careers, and population heterogeneity: Specification and

estimation of a nonparametric, mixed Poisson model. Criminology, 31, 327362.

Nagin, D. S., & Piquero, A. R. (2010). Using the group-based trajectory model to study crime over the life

course. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 21, 105116.

National Association of Police Athletic/Activities Leagues, Inc. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.nationalpal.org

Nofziger, S., & Williams, L. S. (2005). Perceptions of police and safety in a small town. Police Quarterly, 8,

248270.

Nylund, K. L., & Masyn, K. E. (2008). Covariates and latent class analysis: Results of a simulation study. Paper

presented at the Society for Prevention Research Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA.

Piliavin, I., & Briar, S. (1964). Police encounters with juveniles. American Journal of Sociology, 70,

206214.

Piquero, A. R., Fagan, J., Mulvey, E. P., Steinberg, L., & Odgers, C. (2005). Developmental trajectories of legal

socialization among serious adolescent offenders. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 96, 267298.

Portune, R. (1971). Changing adolescent attitudes toward the police: A practical sourcebook for schools and

police departments. Cincinnati, OH: W.H. Anderson and Company.

Puzzanchera, C., & Adams, B. (2011). Juvenile arrests 2009. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and

Delinquency Prevention.

Raudenbush, S. W. (2001). Comparing personal trajectories and drawing causal inferences from longitudinal

data. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 501525.

Rosenbaum, D. P., Schuck, A. M., Costello, S. K., Hawkins, D. F., & Ring, M. K. (2005). Attitudes toward the

police: The effects of direct and vicarious experiences. Police Quarterly, 8, 343365.

Sampson, R. J. (1985). Sex differences in self-reported delinquency and official records: A multiple-group

structural modeling approach. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 1, 345367.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (2003). Life-course desisters? Trajectories of crime among delinquent boys

followed to age 70. Criminology, 42, 555592.

Scaglion, R., & Condon, R. (1980). Determinants of attitudes toward city police. Criminology, 17, 485494.

Stewart et al.

17

Schafer, J. A., Huebner, B. M., & Bynum, T. S. (2003). Citizen perceptions of police services: Race, neighbourhood context, and community policing. Police Quarterly, 6, 440468.

Skolnick, J. H., & Bayley, D. H. (1988). Theme and variation in community policing. In M. Tonry & N. Morris

(Eds.), Crime and Justice (Vol. 10, pp. 127). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Smith, D. A., Graham, N., & Adams, B. (1991). Minorities and the police: Attitudinal and behavior questions.

In M. J. Lynch & E. B. Patterson (Eds.), Race and criminal justice (pp. 2225). Albany, NY: Harrow and

Heston Publishers.

Smith, P. E., & Hawkins, R. O. (1973). Victimization, types of police-citizen contacts, and attitudes toward the

police. Law & Society Review, 8, 135152.

Snyder, H. N. (2008). Juvenile arrests 2006. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency

Prevention.

Snyder, H., & Sickmund, M. (1996). Juvenile offenders and victims: A national report. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Justice.

Snyder, H., & Sickmund, M. (2006). Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006 national report. Washington, DC: U.

S. Department of Justice.

Sullivan, P. R., Dunham, R., & Alpert, G. (1987). Age structure of different ethnic groups concerning police.

The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 78, 177196.

Taylor, T. J., Turner, K. B., Esbensen, F.-A., & Winfree, L. T. Jr. (2001). Coppin an attitude: Attitudinal

differences among juveniles toward the police. Journal of Criminal Justice, 29, 295305.

Truman, J. L. (2011). Criminal victimization, 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Tyler, T. R. (1990). Why people obey the law. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Tyler, T. R. (Ed.). (2007). Legitimacy and criminal justice: International perspectives. New York, NY: Russell

Sage Foundation.

Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts.

New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Walker, S., & Katz, C. (2011). The police in America: An introduction (7th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Warr, M. (2002). Companions in crime: The social aspects of criminal conduct. New York, NY: Cambridge

University Press.

Weitzer, R., & Tuch, S. A. (2002). Perceptions of racial profiling: Race, class, and personal experience.

Criminology, 40, 435457.

White, H. R., & LaGrange, R. L. (1987). An assessment of gender effects in self report delinquency. Sociological Focus, 20, 195213.

Winfree, L. T., Jr., & Griffiths, C. T. (1977). Adolescent attitudes toward the police: A survey of high school students. In T. Ferdinand (Ed.), Juvenile delinquency: Little brother grows up (pp. 7999). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Worrall, J. L. (1999). Public perceptions of police efficacy and image: The fuzziness of support of support

for the police. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 24, 4766.

Wycoff, M. A. (1988). The benefits of community policing: Evidence and conjecture. In J. R. Greene & S.

Mastrofski (Eds.), Community policing: Rhetoric or reality (pp. 103120). Westport, CT: Praeger

Publishers.

Zanna, M. P., & Rempel, J. K. (1988). Attitudes: A new look at an old concept. In D. Bar-Tal & A. W. Kruglanski

(Eds.), The social psychology of knowledge (pp. 315334). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Author Biographies

Daniel M. Stewart is an assistant professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at the University

of North Texas. His current research interests include policing, organizational behavior, and sentencing policy.

18

Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 00(0)

Robert G. Morris, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Criminology and a Director of the Center for

Crime and Justice Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas. His research encompasses contemporary issues in criminal justice and criminology and has been published in journals such as Justice

Quarterly, Journal of Quantitative Criminology, Crime and Delinquency, Criminal Justice and

Behavior, and Intelligence.

Henriikka Weir is an assistant professor of criminal justice at University of Colorado Colorado

Springs as well as a former police officer. Her research interests include policing, substance abuse,

child maltreatment, violence, and biosocial criminology.

Вам также может понравиться

- Attitudes Towards Police in Canada 2012Документ16 страницAttitudes Towards Police in Canada 2012Alina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Ingram, J. Terril, W. Paoline E. 2018. Police Culture and Officer Behavior.Документ32 страницыIngram, J. Terril, W. Paoline E. 2018. Police Culture and Officer Behavior.Gissela RemolcoyОценок пока нет

- Police Accountability: Perception of Police Personnel On Misconduct of Fellow Law EnforcersДокумент37 страницPolice Accountability: Perception of Police Personnel On Misconduct of Fellow Law EnforcersLeu Gim Habana PanuganОценок пока нет

- WOLFE - 2011 - Organizacional Justice and Police MisconductДокумент22 страницыWOLFE - 2011 - Organizacional Justice and Police MisconductPierressoОценок пока нет

- Feeling BlueДокумент22 страницыFeeling BlueDaniel BalofskyОценок пока нет

- LerouxMcShane2017 YouthpolicingДокумент14 страницLerouxMcShane2017 YouthpolicingfidelОценок пока нет

- Police Supervisors Work-Related Attitude PDFДокумент20 страницPolice Supervisors Work-Related Attitude PDFCurumim AfrilОценок пока нет

- Ostale Teme: K C M SДокумент16 страницOstale Teme: K C M StariqnabzОценок пока нет

- Goff Lit Review FinalДокумент6 страницGoff Lit Review Finalapi-242133848Оценок пока нет

- Being A Blue Blood: A Phenomenological Study On The Lived Experiences of Police Officers' ChildrenДокумент29 страницBeing A Blue Blood: A Phenomenological Study On The Lived Experiences of Police Officers' ChildrenLeah Moyao-DonatoОценок пока нет

- Desistance From Antisocial ActivityДокумент24 страницыDesistance From Antisocial ActivityCarlosLeyva123Оценок пока нет

- Police Visibility: Privacy, Surveillance, and the False Promise of Body-Worn CamerasОт EverandPolice Visibility: Privacy, Surveillance, and the False Promise of Body-Worn CamerasОценок пока нет

- Level of Satisfaction To The Service and Response of Police Officers of The Residence in A Barangay in Bacolod CityДокумент6 страницLevel of Satisfaction To The Service and Response of Police Officers of The Residence in A Barangay in Bacolod CityKeil Ezon GanОценок пока нет

- 2021 06 03 Systematic Review Presence PreprintДокумент45 страниц2021 06 03 Systematic Review Presence PreprintANN TRICIA HAVANAОценок пока нет

- How Kids View CopsДокумент15 страницHow Kids View CopsIrisha AnandОценок пока нет

- Does Racial Discrimination Matter - Explaining Perceived Police Bias Across Four Racial Ethnic GroupsДокумент19 страницDoes Racial Discrimination Matter - Explaining Perceived Police Bias Across Four Racial Ethnic GroupsMario DiegoОценок пока нет

- Related Studies Local and ForeignДокумент9 страницRelated Studies Local and ForeignBenj LadesmaОценок пока нет

- Perceptions of Police Scale POPS Measuring AttitudДокумент10 страницPerceptions of Police Scale POPS Measuring AttitudJalesia HortonОценок пока нет

- Restore Police Ligitimacy, Social Capital, and Policing Styles To Improve Police Community RelationsДокумент21 страницаRestore Police Ligitimacy, Social Capital, and Policing Styles To Improve Police Community RelationsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Public-Police Relation-Performance and PerceptionsДокумент16 страницPublic-Police Relation-Performance and PerceptionsMich-s Michaellester Ordoñez MonteronОценок пока нет

- Enhancing Police LegitimacyДокумент17 страницEnhancing Police LegitimacyOscar Contreras VelascoОценок пока нет

- Servant Leadership and Police Officers Job SatisfactionДокумент16 страницServant Leadership and Police Officers Job Satisfactionashraf-0220Оценок пока нет

- Articol Delicventa JuvenilaДокумент43 страницыArticol Delicventa JuvenilaBianca TekinОценок пока нет

- Public Trust in The Myanmar Police Force: Exploring The Influencing FactorsДокумент12 страницPublic Trust in The Myanmar Police Force: Exploring The Influencing FactorsSelf ConceptОценок пока нет

- Dissertation Youth CrimeДокумент7 страницDissertation Youth CrimeWhatAreTheBestPaperWritingServicesNaperville100% (1)

- Vol. 3, No. 4 April 2016Документ4 страницыVol. 3, No. 4 April 2016Nilofa YasminОценок пока нет

- Research Paper Community PolicingДокумент11 страницResearch Paper Community Policinghbkgbsund100% (1)

- Perception of Police Amongst University Students: A Qualitative AnalysisДокумент12 страницPerception of Police Amongst University Students: A Qualitative AnalysisAnukriti RawatОценок пока нет

- Is Mobile Gaming Can Affect The Students AcademicДокумент14 страницIs Mobile Gaming Can Affect The Students AcademicRegine BlancaОценок пока нет

- Crime & Delinquency 2008 Cernkovich 3 33Документ31 страницаCrime & Delinquency 2008 Cernkovich 3 33Teodora RusuОценок пока нет

- Community Policing DissertationДокумент6 страницCommunity Policing DissertationCollegePapersHelpUK100% (1)

- Police Trust ResearchДокумент43 страницыPolice Trust Researchgrantlomuntad1Оценок пока нет

- Another RRLДокумент6 страницAnother RRLKarenKaye JimenezОценок пока нет

- Police Perspectives On Interviewing Older Adult Victims and Witnesses: Preliminary Findings and Call For Future ResearchДокумент22 страницыPolice Perspectives On Interviewing Older Adult Victims and Witnesses: Preliminary Findings and Call For Future Researchjuanchito perezОценок пока нет

- Kay Kyle ToДокумент13 страницKay Kyle ToNell0% (1)

- FarringtonДокумент9 страницFarringtonYashvardhan sharmaОценок пока нет

- Comparing Volunteer Policing Msia, UK, US Cheah Et Al. (2021)Документ14 страницComparing Volunteer Policing Msia, UK, US Cheah Et Al. (2021)Muhammad HailmiОценок пока нет

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Introduction to the Criminal Justice System and the Sociology of CrimeОт EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Introduction to the Criminal Justice System and the Sociology of CrimeОценок пока нет

- JIV Version Preliminar Uso Interno UdecДокумент36 страницJIV Version Preliminar Uso Interno UdecMaruzzella ValdiviaОценок пока нет

- Does The Stereotypical Personality Reported For The Male Police Officer Fit That of The Female Police OfficerДокумент2 страницыDoes The Stereotypical Personality Reported For The Male Police Officer Fit That of The Female Police OfficerIwant HotbabesОценок пока нет

- Exercise 1: Research Topic, Review of The Literature, & Formulating The Question(s)Документ13 страницExercise 1: Research Topic, Review of The Literature, & Formulating The Question(s)Ryan SuapengcoОценок пока нет

- Eileen Vizard JCPP Review 171112Документ27 страницEileen Vizard JCPP Review 171112Ecaterina IacobОценок пока нет

- Controlling Police Street Level DiscretionДокумент20 страницControlling Police Street Level DiscretionOscar Contreras VelascoОценок пока нет

- RRL Foriegn 1.) According To Jonathan Jackson and Elizabeth A. Stanko Public Confidence in Policing Has Become AnДокумент4 страницыRRL Foriegn 1.) According To Jonathan Jackson and Elizabeth A. Stanko Public Confidence in Policing Has Become Anjuliepineda.acadsОценок пока нет

- Forensic Issue DiscussionДокумент2 страницыForensic Issue Discussionlove.nakwonОценок пока нет

- Jang 2010Документ12 страницJang 2010Self ConceptОценок пока нет

- This Is A Very Salient Topic in The United States As Many Areas Are Becoming GentrifiedДокумент8 страницThis Is A Very Salient Topic in The United States As Many Areas Are Becoming GentrifiedOca AbuanОценок пока нет

- PNPДокумент12 страницPNPReymil de JesusОценок пока нет

- Police Officers Require Higher EducationДокумент8 страницPolice Officers Require Higher Educationapi-403494662Оценок пока нет

- Improving Police: What's Craft Got To Do With It?Документ14 страницImproving Police: What's Craft Got To Do With It?PoliceFoundation100% (2)

- Factors Affecting Public Trust in Police A Study of Twin Cities (Rawalpindi & Islamabad)Документ13 страницFactors Affecting Public Trust in Police A Study of Twin Cities (Rawalpindi & Islamabad)John WickОценок пока нет

- Carr Et Al 2007Документ36 страницCarr Et Al 2007Hans FloresОценок пока нет

- A Comparative Study of Satisfaction With The Police in The United States and AustraliaДокумент24 страницыA Comparative Study of Satisfaction With The Police in The United States and AustraliaSuryaОценок пока нет

- Thesis Ton2Документ27 страницThesis Ton2jayson fabrosОценок пока нет

- Program Conferinta 2017Документ1 страницаProgram Conferinta 2017Alina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Grid GerencialДокумент31 страницаGrid GerencialMireille Gonz0% (1)

- OlsДокумент43 страницыOlsAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Collection of Surveys: Appendix CДокумент17 страницCollection of Surveys: Appendix CAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Effect Size Calculator 17Документ5 страницEffect Size Calculator 17Alina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- PT PrintДокумент51 страницаPT PrintAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- PT VALORI ESS6 Data Protocol E01 4Документ118 страницPT VALORI ESS6 Data Protocol E01 4Alina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Kontio Ethical Alternatives PDFДокумент13 страницKontio Ethical Alternatives PDFAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Scale Description: Perceived Autonomy Support: The Climate QuestionnairesДокумент17 страницScale Description: Perceived Autonomy Support: The Climate QuestionnairesAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- (Sixth Edition) - BostonДокумент1 страница(Sixth Edition) - BostonAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Pressure-Cooking Instructions Are Below The Time Table.Документ2 страницыPressure-Cooking Instructions Are Below The Time Table.Alina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Writing The Results SectionДокумент11 страницWriting The Results SectionAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Effect Size and Eta Squared:: in Chapter 6 of The 2008 Book On Heritage Language Learning That You CoДокумент6 страницEffect Size and Eta Squared:: in Chapter 6 of The 2008 Book On Heritage Language Learning That You CoAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Measuring Police Integrity PDFДокумент11 страницMeasuring Police Integrity PDFAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Ivcovick 2Документ24 страницыIvcovick 2Alina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- GEUC 2014 Program Lung FinalДокумент21 страницаGEUC 2014 Program Lung FinalAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Timp Oala Presiune 2Документ3 страницыTimp Oala Presiune 2Alina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- To Serve and Collect - Measuring Police CorruptionДокумент59 страницTo Serve and Collect - Measuring Police CorruptionAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- Presentation Tips Images BlueДокумент36 страницPresentation Tips Images BlueAlina CiabucaОценок пока нет

- FC Exercises3Документ16 страницFC Exercises3Supertj666Оценок пока нет

- BUCA IMSEF 2021 Jury Evaluation ScheduleДокумент7 страницBUCA IMSEF 2021 Jury Evaluation SchedulePaulina Arti WilujengОценок пока нет

- MPDFДокумент10 страницMPDFshanmuganathan716Оценок пока нет

- Excel VBA Programming For Solving Chemical Engineering ProblemsДокумент42 страницыExcel VBA Programming For Solving Chemical Engineering ProblemsLeon FouroneОценок пока нет

- Brochure Exterior LightingДокумент49 страницBrochure Exterior Lightingmurali_227Оценок пока нет

- Missing Person ProjectДокумент9 страницMissing Person ProjectLaiba WaheedОценок пока нет

- Guide For H Nmr-60 MHZ Anasazi Analysis: Preparation of SampleДокумент7 страницGuide For H Nmr-60 MHZ Anasazi Analysis: Preparation of Sampleconker4Оценок пока нет

- Awb 4914934813Документ1 страницаAwb 4914934813Juandondr100% (1)

- Sony DVD Player Power Circuit DiagramДокумент40 страницSony DVD Player Power Circuit DiagramHariyadiОценок пока нет

- Bibliografi 3Документ3 страницыBibliografi 3Praba RauОценок пока нет

- Lifestyle Mentor. Sally & SusieДокумент2 страницыLifestyle Mentor. Sally & SusieLIYAN SHENОценок пока нет

- Almugea or Proper FaceДокумент5 страницAlmugea or Proper FaceValentin BadeaОценок пока нет

- PDF - Gate Valve OS and YДокумент10 страницPDF - Gate Valve OS and YLENINROMEROH4168Оценок пока нет

- Restrictions AOP30 enДокумент1 страницаRestrictions AOP30 enRicardo RamirezОценок пока нет

- Kelompok CKD - Tugas Terapi Modalitas KeperawatanДокумент14 страницKelompok CKD - Tugas Terapi Modalitas KeperawatanWinda WidyaОценок пока нет

- Week 14 Report2Документ27 страницWeek 14 Report2Melaku DesalegneОценок пока нет

- Preview - ISO+8655 6 2022Документ6 страницPreview - ISO+8655 6 2022s7631040Оценок пока нет

- Examen Inglés de Andalucía (Ordinaria de 2019) (WWW - Examenesdepau.com)Документ2 страницыExamen Inglés de Andalucía (Ordinaria de 2019) (WWW - Examenesdepau.com)FREESTYLE WORLDОценок пока нет

- Definition, Scope and Nature of EconomicsДокумент29 страницDefinition, Scope and Nature of EconomicsShyam Sunder BudhwarОценок пока нет

- Headworks & Barrage: Chapter # 09 Santosh Kumar GargДокумент29 страницHeadworks & Barrage: Chapter # 09 Santosh Kumar GargUmer WaheedОценок пока нет

- Risk LogДокумент1 страницаRisk LogOzu HedwigОценок пока нет

- Inspection List For Electrical PortableДокумент25 страницInspection List For Electrical PortableArif FuadiantoОценок пока нет

- Lab Science of Materis ReportДокумент22 страницыLab Science of Materis ReportKarl ToddОценок пока нет

- Cutting Aws C5.3 2000 R2011Документ33 страницыCutting Aws C5.3 2000 R2011Serkan AkşanlıОценок пока нет

- Data Structures and Algorithms AssignmentДокумент25 страницData Structures and Algorithms Assignmentعلی احمد100% (1)

- Smartor manualENДокумент148 страницSmartor manualENPP043100% (1)

- Seventh Pay Commission ArrearsДокумент11 страницSeventh Pay Commission Arrearssantosh bharathyОценок пока нет

- If You Restyou RustДокумент4 страницыIf You Restyou Rusttssuru9182Оценок пока нет

- Gravitational Fields 1Документ18 страницGravitational Fields 1Smart linkОценок пока нет

- (LS 1 English, From The Division of Zamboanga Del SurДокумент17 страниц(LS 1 English, From The Division of Zamboanga Del SurKeara MhieОценок пока нет