Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Health Care For Women International

Загружено:

quinhoxОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Health Care For Women International

Загружено:

quinhoxАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

This article was downloaded by: [University of Veracruzana]

On: 20 August 2015, At: 11:10

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG

Health Care for Women International

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uhcw20

Autonomy and Social Norms in a Three

Factor Grief Model Predicting Perinatal

Grief in India

a

Lisa R. Roberts & Jerry W. Lee

School of Nursing , Loma Linda University , Loma Linda ,

California , USA

b

Department of Health Promotion and Education, School of Public

Health , Loma Linda University , Loma Linda , California , USA

Accepted author version posted online: 13 May 2013.Published

online: 18 Jul 2013.

Click for updates

To cite this article: Lisa R. Roberts & Jerry W. Lee (2014) Autonomy and Social Norms in a Three

Factor Grief Model Predicting Perinatal Grief in India, Health Care for Women International, 35:3,

285-299, DOI: 10.1080/07399332.2013.801483

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2013.801483

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or

howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising

out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions

Health Care for Women International, 35:285299, 2014

Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0739-9332 print / 1096-4665 online

DOI: 10.1080/07399332.2013.801483

Autonomy and Social Norms in a Three Factor

Grief Model Predicting Perinatal Grief in India

LISA R. ROBERTS

School of Nursing, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, California, USA

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

JERRY W. LEE

Department of Health Promotion and Education, School of Public Health, Loma Linda

University, Loma Linda, California, USA

Perinatal grief following stillbirth is a significant social and mental health burden. We examined associations among the following latent variables: autonomy, social norms, self-despair, strained

coping, and acute griefamong poor, rural women in India who

experienced stillbirth. A structural equation model was built and

tested using quantitative data from 347 women of reproductive age

in Chhattisgarh. Maternal acceptance of traditional social norms

worsens self-despair and strained coping, and increases the autonomy granted to women. Greater autonomy increases acute grief.

Greater despair and acute grief increase strained coping. Social

and cultural factors were found to predict perinatal grief in India.

Stillbirth is a significant global public health problem with multiple etiologies.

Perinatal grief following stillbirth is a significant social and mental health burden. Therefore, in India, where stillbirth rates are high, perinatal grief affects

the day-to-day life of many women (Roberts, Anderson, Lee, & Montgomery,

2012a; Roberts, Montgomery, Lee, & Anderson, 2012b).

Our objective in this study was to examine associations among latent

variables of perinatal grief among poor, rural women of central India who

had experienced stillbirth. A structural equation model was built and tested

using quantitative data from women of reproductive age. We were compelled

to better understand predictors of perinatal grief within the cultural context

so that appropriate interventions may be undertaken in the future.

Received 15 July 2012; accepted 24 April 2013.

Address correspondence to Lisa R. Roberts, School of Nursing, Loma Linda University,

11262 Campus Street, West Hall, Loma Linda, CA 92350-0001, USA. E-mail: lroberts@llu.edu

285

286

L. R. Roberts and J. W. Lee

While perinatal grief predictors are well documented in Western countries, this study adds to the limited literature on perinatal grief in non-Western

countries.

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

BACKGROUND

Stillbirth is a significant global public health problem with multiple etiologies (Kramer, 2003; Lawn et al., 2009b; Rubens, Gravett, Victora, & Nunes,

2010). In addition to medical causes, indirect casual factors include lack of

antenatal care (Di Mario, Say, & Lincetto, 2007), poverty (Lawn et al., 2009a),

and social norms facilitating gender discrimination. Gender discrimination in

India results in disparity of female education (Korde-Nayak Vaishali & Gaikwad Pradeep, 2008), early marriage (Croll, 2000), and low female autonomy

(Lee et al., 2009; Yesudian, 2009), each of which are known risk factors for

stillbirth (Lawn et al., 2009b).

Therefore, maternal coping with stillbirth cannot be studied without

necessarily considering womens status. As stated by Lee Jong-Wook, former

Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), Mothers, the

newborn, and children represent the well-being of society and its potential

for the future (WHO, 2005, p. xi). Womens status in India is a summation of

a number of factors including education, economic activity, decision-making

authority, personal freedom of movement, control over economic resources,

reproductive rights, land ownership, age at marriage, spousal age difference, joint family residence, socialization of secondary status, and health

(Jejeebhoy & Sathar, 2001; Mathur, 2008). Womens autonomy is generally

acknowledged to be low in developing nations, and specifically in India

(Barua & Kurz, 2001; Clarke & Clarke, 2009; Croll, 2000; Mistry, Galal, & Lu,

2009; Yesudian, 2009). Bloom, Wypij, and Gupta (2001) define womens autonomy in India as interpersonal control, characterized by a womans ability

to control or make decisions regarding concerns in her life, even though

family members may oppose her wishes.

Womens autonomy, however, cannot be understood outside of the

overarching social norms in India. India is a patriarchal society in which

women are transferred between patrilines at the time of marriage and live

with affinal kin (Bloom et al., 2001, p. 68). In other words, upon marriage

women leave their natal kin to live with their husbands family. Their autonomy, therefore, must be understood within this social context. After marriage

a woman is no longer considered a member of her natal kins family. Her

status in her new family is determined by her fertility, her ability to produce

at least one son, and her age in relationship to her sisters-in-law. At the

beginning of her marriage, as the newest member of the household, she has

the lowest social status within the household hierarchy (Bloom et al., 2001;

Croll, 2000).

Predictors of poor coping with perinatal grief in Western societies

have included emotion-focused coping strategies, maladaptive coping skills,

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

Model Predicting Perinatal Grief in India

287

perceived lack of social support, and intense emotionality at the time of

stillbirth (Bennett, Litz, Maguen, & Ehrenreich, 2008; Cacciatore, Schnebly,

& Froen, 2009; Engler & Lasker, 2000). The dearth of data pertaining to

Indian womens perinatal grief limits our understanding of factors that

predict their coping with the loss. Social norms, however, may influence

perinatal grief in this setting. Examples of social norms pertaining to birthing

practices in India can be found in the literature: a strict code of practices and

expected behaviors during the postpartum period for women (Ramakrishna,

Ganapathy, Matthews, Mahendra, & Kilaru, 2008), social consequences for

women without children include divorce or shunning (Joshi, Dhapola, &

Pelto, 2008), prohibition from being present at the babys burial due to

religious beliefs (Gatrad, Ray, & Sheikh, 2004), and conferral of blessings

only for the birth of a son (Garg & Nath, 2008); furthermore, women

who suffer stillbirth are stigmatized (Sather, Fajon, Zaentz, & Rubens,

2010).

While the Indian medical society has not traditionally acknowledged

perinatal grief as a significant problem (Mehta & Verma, 1990), more recent

studies have shown that perinatal grief is not a Western phenomenon (Mammen, 1995) and perinatal grief is indeed a significant problem and social

burden in India (Roberts et al., 2012b) that can negatively impact womens

health.

The purpose of this study was to examine associations among autonomy

(womens freedom of movement without permission), acceptance of social

norms regarding stillbirth, self-despair (helplessness and hopelessness),

strained coping (difficulty with everyday life and social interactions), and

acute grief (anguish regarding the stillborn baby) by examining causal pathways to perinatal grief among poor, rural women of central India who had

experienced stillbirth. A conceptual model was theoretically developed;

structural equation modeling (SEM) was then used to explore the model

fitness. We hypothesized that (a) women with lower autonomy would

have higher perinatal grief scores due to a lack freedom to exercise any

practical coping, thereby relying heavily on emotion focused coping which

is associated with increased perinatal grief (Engler & Lasker, 2000), and

that (b) women with traditional views toward social norms would have

greater perinatal grief due to inhibited expression of grief proscribed by

social expectations and the stigma and blame attached to stillbirth (Sather

et al., 2010; Stanton, Lawn, Rahman, Wilczynska-Ketende, & Hill, 2006).

Additionally, the internationally validated Perinatal Grief Scale (PGS) was

expected to perform reliably in our study population. Toedter, Lasker, and

Janssen (2001) reviewed 22 studies in four Western countries to validate the

PGS in widely varying samples. As a result, the authors state that PGS has

excellent reliability and generalizability. The authors also found remarkable

similarities of grief predictors among these studies done with samples in

three European countries and the United States.

288

L. R. Roberts and J. W. Lee

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

These data were gathered from a cohort of 355 poor, rural women of central India (see Table 1) as part of a larger mixed-methods study exploring

womens perceptions of stillbirth and factors that inhibit or enhance coping

with perinatal grief (Roberts et al., 2012a; Roberts et al., 2012b). Structured

interviews were used to collect demographics as well as measure acceptance

of social norms pertaining to expectations of womens response to stillbirth,

perceived social provision of support, intrinsic religiosity, coping methods,

autonomy, and perinatal grief. Cases with any missing data on the variables

used in this analysis were excluded, reducing the cohort to 347.

Measures

Control variables. Initial analyses showed demographic variables such

as education and age, were unrelated to our five primary constructs and

therefore were not included as control variables.

Latent constructs. Our structural equation model (SEM) was designed

around five constructs: social norms, autonomy, despair, difficulty coping,

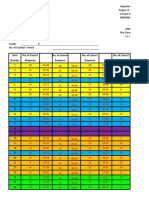

TABLE 1 Sample Demographics (N = 355): Comparing Participants With a History of Stillbirth and Those Without a History of Stillbirth

Item

Scheduled tribe (ST)

Scheduled castes (SC)

Other backward castes (OBC)

Hindu

Women of reproductive age with no

education

Birth intervals < 2 years

Report of domestic violence

Ever had a sonogram

Women reporting no health problems

Tobacco and/or paan used

Mean age at first delivery

Birth control pill use among rural women of

reproductive age

No form of contraceptive used

Total fertility rate

p

Had stillbirth

(n = 178)

No stillbirth

(n = 177)

14.6% (N = 26)

31.5% (N = 56)

46.6% (N = 83)

100% (N = 178)

53.9% (N = 96)

6.2% (N = 11)

35.0% (N = 62)

49.7% (N = 88)

98.9% (N = 175)

41.8% (N = 74)

81.4% (N = 144)

20.3% (N = 36)

43.3% (N = 77)

63.5% (N = 113)

25.3% (N = 45)

19.01 (2.17)

0.6% (N = 1)

78.3% (N = 137)

13.6% (N = 24)

29.4% (N = 52)

81.9% (N = 145)

13.6% (N = 24)

18.74 (2.28)

1.1% (N = 2)

86.0% (N = 153)

4.6

83.6% (N = 148)

2.7

< .05, p < .01.

Note: ST, SC, OBC are people groups at the bottom of the Indian social stratification system and have

previously been known by such designations as untouchables, harijans, outcastes, and depressed classes

and are currently also known as dalits (Sachchidananda, 1993). Paan is a chewing mixture of areca nut

and lime wrapped in a betel leaf or a similar variation (Gandhi, Kaur, & Sharma, 2005).

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

Model Predicting Perinatal Grief in India

289

and active grief. Each construct was formed from three to seven manifest

variables as described below. All Cronbachs statistics were calculated on

our full sample of women.

Demographics. Independent variables included age, ethnicity, and religion, and additional pertinent information such as maternal age at first

delivery, education level, socioeconomic status, household position (head of

household/widow, wife, daughter-in-law, or daughter), gender roles, contraceptive use, family composition, and history of domestic violence.

Autonomy. An autonomy scale was derived from questions in a previous study done in India (Mistry et al., 2009). The authors defined autonomy

as a womans freedom to exercise her own judgment in order to act in her

own interest and extracted data from the 19981999 National Family Health

Survey-2 for married, rural women ages 15 to 49 who had at least one

singleton birth.

Initially all six questions used by Mistry and colleagues (2009) were

used in this study as an autonomy; scale with a summed index score with

higher scores indicating greater autonomy; however, the Cronbach alpha

was abysmal (.14). Therefore, two items were droppedspecifically two

items regarding decision making as it pertains to buying a major household

item and going to stay at natal kinswhich resulted in a much improved

Cronbach alpha (.54). The women in our study were very poor, and buying

a major household item was not something they could relate to very wellit

simply is not within the realm of their realty to even consider this. Likewise,

once married, our sample women live with their husbands family and rarely

leave their homes. As expressed by a mother-in-law in phase one of our

study, She came here after marriage; now she should live here and she

should die here. Always she should be here, her husband her only focus.

Therefore, the item regarding staying with natal kin did not track well with

our study population. Thus, while the initial autonomy scale was also developed in an Indian context, further contextualization to our target women

was required due to the vast diversity of India that, taken as a whole, hides

the variance of many subgroups and their unique cultures, languages, and

traditions.

Social norms. The acceptance of social norms scale was designed to

measure womens attitudes toward social norms on a continuum of agreement with traditional social norms to disagreement with traditional social

norms. The social norms questions were derived from the literature and

included (a) expectations regarding the appropriate age for women to be

married (Croll, 2000), (b) mothers-in-law expectations for offspring within a

year of marriage (Barua & Kurz, 2001), (c) expression of grief after a baby is

lost (Mehta & Verma, 1990), (d) shame after stillbirth, (e) being blamed by

others for the stillbirth (Sather et al., 2010), and (f) preference for a son (Garg

& Nath, 2008; Gatrad et al., 2004). Two items dealt with son preference; one

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

290

L. R. Roberts and J. W. Lee

to elicit maternal attitude and one to elicit repercussions of having a male

versus female stillbirth. Womens acceptance of social norms was ascertained using seven questions with a 3-point Likert-type scale (agree, neutral,

disagree). Social norm questions were represented by an index score as a

continuous variable, with low scores indicating traditional views and higher

scores indicating progressive views. The 7-item scale, summed for an index

score of 0 to 14, had a Cronbach alpha of .50.

Perinatal grief. The internationally validated (Toedter, Lasker, &

Janssen, 2001) PGS-33 is a reliable measure of maternal grief with three

factor-analyzed 11-item subscales measuring active grief, difficulty coping,

and despair with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree)

to 5 (strongly agree) (Potvin, Lasker, & Toedter, 1989). For scoring, all items

were summed, so that higher scores reflect more severe grief. An index score

(33 to 165) represented perinatal grief as a continuous variable (Cronbachs

alpha = .91).

Analysis

We used Amos and SPSS 20 to generate data sets for SEM and run descriptive

statistics. Exploratory factor analysis was utilized to eliminate items based

on principal component analysis. Models were built for autonomy, social

norms, self-despair, strained coping, and acute grief. Then structural equation modeling was performed using Amos 20 to examine the causal relationships among the latent variables. Root mean square error of approximation

(RMSEA) and comparative fit index (CFI) were utilized to judge how well

the model fit the data.

RESULTS

To explore how autonomy, social norms, and perinatal grief related to one an

other and with demographics and pregnancy-related variables simple linear

regressions were performed with autonomy, social norms, and perinatal grief

as the dependent variables. The results are shown in Table 2.

Predictors of Autonomy

Only education and social norms predicted autonomy in the simple linear

regressions. When multiple regression was used to regress autonomy on

all the variables in Table 2, again, only education and response to social

norms were significant predictors of autonomy (p = .033 and .003, respectively), and very little of the variance (R 2 = .07) in autonomy was explained.

291

Model Predicting Perinatal Grief in India

TABLE 2 Simple Linear Regression of Autonomy, Social Norms, and Perinatal Grief on Each

Demographic, and on Each Other, Among All Study Participants (N = 355)

Autonomy

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

Item

Age

Ethnicity

Household position

Victim of domestic violence

Contraceptive use

Number of living sons

Number of living daughters

Education

Comparative SES

Maternal age at 1st delivery

Number of pregnancies

Ever had a sonogram

Number of stillbirths

Social norms

Autonomy

Note. p < .05,

0.05

0.01

0.02

0.06

0.06

0.07

0.06

0.16

0.03

0.07

0.01

0.07

0.01

0.18

p

.373

.856

.680

.236

.272

.161

.250

.002

.552

.208

.866

.171

.885

.001

Social norms

Perinatal grief

0.11

0.06

0.05

0.11

0.11

0.14

0.10

0.18

0.03

0.15

0.22

0.06

0.13

.049

.235

.391

.048

.033

.009

.071

.001

.562

.004

.000

.277

.014

0.18

.001

0.04

0.07

0.01

0.08

0.10

0.06

0.01

0.14

0.01

0.14

0.15

0.03

0.21

0.50

0.09

.492

.186

.987

.148

.059

.286

.926

.009

.880

.010

.004

.552

.000

.000

.086

< .01

Predictors of Social Norms

Age, history of domestic violence, contraceptives, number of living sons,

education, age at first delivery, number of pregnancies, number of stillbirths,

and autonomy were significant predictors of response to social norms (see

Table 2). When the social norms variable was regressed on all of the independent variables, however, only contraceptives, number of pregnancies,

and autonomy were significant (p = .014, .019, .003, respectively), and only

a small amount of variance was explained (R 2 = .13).

Predictors of Perinatal Grief

In simple linear regressions, education, age at first delivery, number of pregnancies, number of stillbirths, and social norms were significant predictors

of perinatal grief (see Table 2). Perinatal grief was then regressed on all

the other variables jointly and only one variablesocial normwas highly

significant (p < .01). Finally, perinatal grief was regressed on the variables

that had been significant on the above multiple linear regressions (MLRs);

namely, contraceptives, education, number of pregnancies, autonomy, and

social norms. Once again, only social norms was significant (p < .01), with

moderate variance explained (R 2 = .26).

Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis was applied to reduce variables of autonomy, social norms, and perinatal grief, and principal component analysis was used

292

L. R. Roberts and J. W. Lee

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

to obtain the main factors among the variables. Table 3 shows the variables kept for each factor extracted. Of note, three factors were confirmed

for perinatal grief; however, the items correlated differently for our cohort

than that described by Potvin and colleagues (1989). There was some degree of overlap between our factors and Potvin and colleagues factors, and

while representing the same essence of their factors, we felt it necessary

to rename our factors. Thus, we titled our three factors of perinatal grief

self-despair, strained coping, and acute grief. For comparison to Potvin and

colleagues factors (despair, difficulty coping, and active grief), please see

Table 3.

Structural Equation Modeling

Our causal model included 20 manifest variables as shown in Figure 1.

Direct effects. Initially we ran the causal model shown in Figure 1 with

direct paths from education to autonomy, autonomy to social norms, and

social norms to perinatal grief. These direct pathways did not meet our statistical significance criterion, and the model was modified. Education was

dropped and direct paths from autonomy to social norms, social norms to

perinatal grief, and autonomy to perinatal grief were explored. Perinatal

grief was then modeled according to the three factorsself-despair, strained

coping, and acute griefreplacing a unitary perinatal grief factor in the

model. The following direct paths did not meet statistical significance and

were dropped from the model: autonomy to self-despair, autonomy to

strained coping, and social norms to acute grief. Additionally, modification indices suggested several logical connections in the error variances

of items; for example, several questions used the phrase since the baby

died or since he or she died, which might have contributed to the correlated error variance. Also, a direct connection was suggested between

the blame myself question and the family ashamed of me due to stillbirth question, which seemed a reasonable connection and it was added.

This resulted in the final model with goodness of fit statistics as shown in

Figure 1.

Acceptance of social norms was positively associated with self-despair

and strained coping, while negatively associated with autonomy. Autonomy

was positively associated with acute grief. Self-despair and acute grief were

both positively associated with strained coping.

Indirect effects. Causal pathways from one variable to another can

be affected by an intervening variable. Note in Figure 1, for example,

that social norms is indirectly connected with acute grief through autonomy. In this respect, an increase in acceptance of social norms was associated with decrease in acute grief, but it did not reach significance

(p = .059).

Model Predicting Perinatal Grief in India

293

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

TABLE 3 Three Factors of Perinatal Grief

Potvin et al.

Our model

Active grief

I feel depressed.

I feel empty inside.

I feel a need to talk about the baby.

I am grieving for the baby.

I am frightened.

I very much miss the baby.

It is painful to recall memories of the loss.

I get upset when I think about him/her.

I cry when I think about him/her.

Time passes so slowly since the baby died.

I feel so lonely since he/she died.

Acute grief

I feel depressed.

Difficulty coping

I find it hard to get along with certain

people.

I cant keep up with my usual activities.

I have considered suicide since the loss.

I feel I have adjusted well to the loss.R

I have let peole down since the baby died.

I get cross at my friends/relatives more than

I should.

Sometimes I feel like I need a professional

counselor to help me get my life together

again.

I feel as though I am just existing and not

really living since he/she died.

I feel somewhat apart and remote even

among friends.

I find it difficult to make decisions since the

baby died.

It feels great to be alive.R

Strained coping

I find it hard to get along with certain people.

Despair

I take medicine for my nerves.

I feel guilty when I think about the baby.

I feel physically ill when I think about the

baby.

I feel unprotected in a dangerous world

since he/she died.

I try to laugh but nothing seems funny

anymore.

The best part of me died with the baby.

I blame myself for the babys death.

I feel worthless since he/she died.

It is safer not to love.

I worry about what my future will be.

Being a bereaved parent means being a

second class citizen.

Self-despair

I feel my nerves are bad.

I feel guilty when I think about the baby.

I feel physically ill when I think about the baby.

I feel a need to talk about the baby.

I am grieving for the baby.

I very much miss the baby.

It is painful to recall memories of the loss.

I get upset when I think about him/her.

I cry when I think about him/her.

I cannot keep up with my usual activities.

I get cross at my friends/relatives more than I

should.

It is safer not to love.

I feel empty inside.

I am frightened.

I feel unprotected in a dangerous world since

he/she died.

I try to laugh but nothing seems funny anymore.

The best part of me died with the baby.

I blame myself for the babys death.

I feel worthless since he/she died.

Because of the stillbirth I feel like an outcast.

I have considered suicide since the loss.

I feel so lonely since he/she died.

I find it hard to concentrate since the baby died.

I feel alone even among friends/family.

I have let people down since the baby died.

I feel as though I am just existing and not really

living since he/she died.

Time passes so slowly since the baby died.

Note: The items are not in the order in which they have been used. = indicates that in our study this item

loaded on a different factor than in Potvin et al. R = Items reverse coded before analysis. Italics indicate

wording of item changed from original wording to accommodate cultural understanding/translation.

294

FIGURE 1 Final causal model on sample with no missing data (n = 347). Standardized regression coefficients from structural equation model are

shown. X 2 = 336.2, df = 159, p < .001, RMSEA = .057 (.048, 0.65), CFI = .935. Numbers on arrows are standardized path coefficients. SB =

stillbirth (color figure available online).

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

Model Predicting Perinatal Grief in India

295

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

DISCUSSION

Acceptance of traditional social norms was associated with increased selfdespair and strained coping. Acceptance of social norms apparently decreased autonomy. Increased autonomy was accompanied by more acute

grief. Greater self-despair and acute grief was associated with increased

strained coping, which suggests how these three aspects of perinatal grief

might be related.

While we had anticipated greater autonomy to have a protective effect

in terms of perinatal grief, we found the opposite to be true. Our hypothesis was that women with increased autonomy would be less isolated and

have greater opportunity for fulfillment through means other than fertility.

Additionally, we hypothesized that those with more autonomy would be

less accepting of traditional social norms and possibly have a wider network

of social supportboth of which were found to have a protective effect

in terms of perinatal grief outcomes in our previous study (Roberts et al.,

2012b). It is possible that the reason autonomy, instead, was associated with

increased acute grief in this context is that with greater autonomy there is

some freedom of choice, which may make it harder to simply accept the stillbirth as ones fate. In traditional Indian society fatalism is pervasive (Lawn

et al., 2009a).

Traditional Indian society is also collectivistic in nature, however, giving

autonomy a different connotation than in Western society. Further consideration of the quality of autonomy measured in our study population boiled

down to whether or not women needed to seek permission to go to the market or visit relatives/friends, which would or would not be granted by her

affinal kin. Our assertion that womens autonomy and social norms in India

are correlated entities was confirmed by this SEM. Maternal acceptance of

traditional social norms may be associated with decreased autonomy simply

because she would never think or dare to go to the market or visit natal kin/friends without seeking permission from her affinal kin. This would

explain why increased acceptance of social norms would be negatively associated with autonomy and at the same time autonomy was associated with

increased acute grief.

Acceptance of social norms affects each of the three factors of perinatal griefself-despair and strained coping directly and acute grief indirectly

through autonomyindicating that maternal acceptance of traditional social norms is associated with perinatal grief. The high acceptance of social

norms involves increased self-despair and strained coping, however, through

decreased autonomy, decreased acute grief.

Yet the increased acute grief associated with increased autonomy may

be protective in the long run. Acute grief following stillbirth could be considered normal (Potvin et al., 1989) and while consensus is lacking as to

the appropriate duration for normal grieving (Woof & Carter, 1997), it does

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

296

L. R. Roberts and J. W. Lee

resolve spontaneously (Kim & Jacobs, 1991). Complicated grief, an intensification of the normal grief response, however, is characterized by the presence of intrusive thoughts, pangs of severe emotion, distressing yearnings,

feeling excessively alone and empty, excessively avoiding tasks reminiscent

of the deceased, unusual sleep disturbances, and maladaptive levels of loss

of interest in personal activities, present more than a year after the loss event,

are indicative of complicated grief disorder (Horowitz et al., 2003). Perinatal

loss creates a propensity for complicated grief (Bennett, Litz, Lee, & Maguen,

2005), and the characteristics of complicated grief thematically map on to the

self-despair and strained coping variables of our study very well. Similarly,

Potvin and colleagues (1989) indicated more severe grief associated with the

progression from active grief to difficulty coping to despair. Therefore, it may

be that acceptance of social norms, associated with self-despair and strained

coping, results in worsened perinatal grief compared with the acute grief associated with increased autonomy among women who are less accepting of

social norms. In essence, acute grief may result in better long-term outcomes.

Longitudinal studies are needed to further investigate this possibility.

Predicting perinatal grief is clearly different in this context than

what is documented in the literature for Western women. Understanding

perinatal grief predictors according to cultural context is important for the

design of future investigations as well as the development of appropriate

interventions. A tailored approach is made possible by careful analysis of

the data.

Strengths and Limitations

This data analysis contributes to the limited literature available on perinatal

grief in India and the social norms and autonomy factors affecting perinatal

grief in the context of poor, rural women. The vast variation of people

groups, religious beliefs, and traditions within India limit generalizability.

Enhanced understanding of the predictors of perinatal grief gained through

this factor analysis and structural equation modeling however, is particularly

helpful when considering possible interventions.

Conclusion

The importance of social norms in this context cannot be ignored. Not only

do traditional social norms contribute to the high levels of grief experienced

in the daily lives of these women (likely by sustaining systematic gender

discrimination), the particular social norms of disparity in female health and

education, son preference, low autonomy, and early marriage and childbearing are risk factors for stillbirth; yet for these women their very identity

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

Model Predicting Perinatal Grief in India

297

and worth are determined by fertility. Therefore, perinatal grief adds tremendously to their already high levels of grief.

Future interventions aimed at reducing mental health and social sequelae resulting from perinatal grief must also address the underlying social

norms that form the backdrop of the lives of Indian women. Until traditional

social norms are challenged, the daily lives of these women will continue to

be burdened with grief. If, on the other hand, these women are encouraged

to adopt progressive attitudes and social norms are addressed within their

families and villages through community education, the women will fare

better if stillbirth does occur.

Additionally, as social norms are addressed through community education, families may be more likely to access antenatal care and facility

deliveries as offered through government and private programs, thus reducing the future incidence of stillbirth, and, at the same time, when stillbirth

does occur families may be more understanding of maternal grief.

Women who are currently grieving may also be more likely to recover

if the pressure of social norms to produce children, particularly sons, is

reduced. These interventions would also likely help lower the general grief

that is so much a part of womens lives in India.

The results of this study add to the limited literature on perinatal grief

among Indian women and other non-Western women whose fertility is

paramount and whose culture perpetuates systematic gender discrimination.

Whether these women are encountered in their countries of origin or as immigrants in Western countries, understanding their cultural paradigm is vital.

Only with an informed approach can we effectively predict perinatal grief

and offer appropriate intervention.

REFERENCES

Barua, A., & Kurz, K. (2001). Reproductive health-seeking by married adolescent

girls in Maharashtra. In M. Koenig, S. Jejeebhoy, J. Cleland, & B. Ganatra (Eds.),

Reproductive health in India: New evidence (pp. 3246). New Delhi, India:

Rawat.

Bennett, S. M., Litz, B. T., Lee, B. S., & Maguen, S. (2005). The scope and impact

of perinatal loss: Current status and future directions. Professional Psychology:

Research and Practice, 36, 180187. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.36.2.180

Bennett, S. M., Litz, B. T., Maguen, S., & Ehrenreich, J. T. (2008). An exploratory

study of the psychological impact and clinical care of perinatal loss. Journal of

Loss & Trauma, 13, 485510.

Bloom, S. S., Wypij, D., & Gupta, M. D. (2001). Dimensions of womens autonomy

and the influence on maternal health care utilization in a North Indian City.

Demography, 38(1), 6778.

Cacciatore, J., Schnebly, S., & Froen, J. F. (2009). The effects of social support on

maternal anxiety and depression after stillbirth. Health & Social Care in the

Community, 17, 167176. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00814.x

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

298

L. R. Roberts and J. W. Lee

Clarke, P., & Clarke, P. B. (2009). The Oxford handbook of the sociology of religion.

New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Croll, E. (2000). Endangered daughters: Discrimination and development in Asia.

London, England: Routledge.

Di Mario, S., Say, L., & Lincetto, O. (2007). Risk factors for stillbirth in developing

countries: A systematic review of the literature. Sexually Transmitted Diseases,

34(7), S11S21. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000258130.07476.e3

Engler, A. I., & Lasker, J. N. (2000). Predictors of maternal grief in the year after a

newborn death. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 8, 227243.

Gandhi, G., Kaur, R., & Sharma, S. (2005). Chewing pan masala and/or betel

quidFashionable attributes and/or cancer menaces? Journal of Human Ecology, 17, 161166.

Garg, S., & Nath, A. (2008). Female feticide in India: Issues and concerns. Journal

of Postgraduate Medicine, 54, 276279.

Gatrad, A. R., Ray, M., & Sheikh, A. (2004). Hindu birth customs. Archives of Disease

in Childhood, 89, 10941097. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.050591

Horowitz, M. J., Siegel, B., Holen, A., Bonanno, G. A., Milbrath, C., & Stinson, C. H.

(2003). Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. Focus, 1, 290298.

Jejeebhoy, S. J., & Sathar, Z. A. (2001). Womens autonomy in India and Pakistan:

The influence of religion and region. Population and Development Review, 27,

687712.

Joshi, A., Dhapola, M., & Pelto, P. J. (2008). Gynaecological problems: Perceptions

and treatment-seeking behaviors of rural Gujarati women. In M. Koenig, S.

Jejeebhoy, J. Cleland, & B. Ganatra (Eds.), Reproductive health in India: New

evidence (pp. 133158). New Delhi, India: Rawat.

Kim, K, & Jacobs, S. (1991). Pathologic grief and its relationship to other psychiatric

disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 21, 257263.

Korde-Nayak Vaishali, N., & Gaikwad Pradeep, R. (2008). Causes of stillbirth. The

Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India, 58, 314318.

Kramer, M. S. (2003). The epidemiology of adverse pregnancy outcomes: An

overview. Journal of Nutrition, 133, 1592S1596S.

Lawn, J., Kinney, M., Lee, A., Chopra, M., Donnay, F., Paul, V., . . . Darmstadt, G.

(2009a). Reducing intrapartum-related deaths and disability: Can the health system deliver? International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 107, S123S142.

doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.021

Lawn, J., Yakoob, M., Haws, R., Soomro, T., Darmstadt, G., & Bhutta, Z. (2009b).

3.2 million stillbirths: Epidemiology and overview of the evidence review. BMC

Pregnancy and Childbirth, 9(Suppl. 1), S2. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-9-S1-S2

Lee, A. C. C., Lawn, J. E., Cousens, S., Kumar, V., Osrin, D., Bhutta, Z. A., . . .

Darmstadt, G. L. (2009). Linking families and facilities for care at birth: What

works to avert intrapartum-related deaths? International Journal of Gynecology

& Obstetrics, 107, S65S88. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.012

Mammen, O. K. (1995). Womens reaction to perinatal loss in India: An exploratory,

descriptive study. Infant Mental Health Journal, 16, 94101.

Mathur, K. (2008). Body as space, body as site: Bodily integrity and womens empowerment in india. Economic and Political Weekly, 43(17), 54.

Mehta, L., & Verma, I. C. (1990). Helping parents to face perinatal loss. Indian

Journal of Pediatrics, 57, 607609.

Downloaded by [University of Veracruzana] at 11:10 20 August 2015

Model Predicting Perinatal Grief in India

299

Mistry, R., Galal, O., & Lu, M. (2009). Womens autonomy and pregnancy care

in rural India: A contextual analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 69, 926933.

doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.008

Potvin, L., Lasker, J., & Toedter, L. (1989). Measuring grief: A short version of the

Perinatal Grief Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment,

11(1), 2945. doi:10.1007/bf00962697

Ramakrishna, J., Ganapathy, S., Matthews, Z., Mahendra, S., & Kilaru, A. (2008).

Health, illness and care in the obstetric period: A prospective study of women

in Rural Karnataka. In M. Koenig, S. Jejeebhoy, J. Cleland, & B. Ganatra (Eds.),

Reproductive health in India: New evidence (pp. 86115). New Delhi, India:

Rawat.

Roberts, L. R., Anderson, B. A., Lee, J. W., & Montgomery, S. (2012a). Grief and

women: Stillbirth in the social context of India. International Journal of Childbirth, 2, 187198. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/2156-5287.2.3.187

Roberts, L. R., Montgomery, S., Lee, J. W., & Anderson, B. A. (2012b). Social and

cultural factors associated with perinatal grief in Chhattisgarh, India. Journal of

Community Health, 37, 572582. doi:10.1007/s10900-011-9485-0

Rubens, C., Gravett, M., Victora, C., & Nunes, T. (2010). Global report on preterm

birth and stillbirth (7 of 7): Mobilizing resources to accelerate innovative solutions (Global Action Agenda). BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 10(Suppl. 1),

S7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S7

Sachchidananda. (1993). Political culture of scheduled castes and tribes: A study

in change. In S. B. Roy & A. K. Ghosh (Eds.), People of India: Bio-cultural

dimensions (pp. 113125). New Delhi, India: Inter-India Publications.

Sather, M., Fajon, A. V., Zaentz, R., & Rubens, C. (2010). Global report on preterm

birth and stillbirth (5 of 7): Advocacy barriers and opportunities. BMC Pregnancy

and Childbirth, 10(Suppl. 1), S5. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S5

Stanton, C., Lawn, J. E., Rahman, H., Wilczynska-Ketende, K., & Hill, K. (2006). Stillbirth rates: Delivering estimates in 190 countries. Lancet, 367(9521), 14871494.

Toedter, L. J., Lasker, J. N., & Janssen, H. M. (2001). International comparison of

studies using the Perinatal Grief Scale: A decade of research on pregnancy loss.

Death Studies, 25, 205228. doi:10.1080/074811801750073251

Woof, W. R., & Carter, Y. H. (1997). The grieving adult and the general practitioner:

A literature review in two parts (Part 2). The British Journal of General Practice,

47(421), 509514.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2005). World Health Report 2005: Make every

mother and child count. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

Yesudian, P. P. (2009). Synergy between womens empowerment and maternal

and peri-natal care utilization. Retrieved from http://iussp2009.princeton.edu/

download.aspx?submissionId=92156

Вам также может понравиться

- Lesson 17 Be MoneySmart Module 1 Student WorkbookДокумент14 страницLesson 17 Be MoneySmart Module 1 Student WorkbookAry “Icky”100% (1)

- Behavioral Treatment For TicsДокумент6 страницBehavioral Treatment For TicsquinhoxОценок пока нет

- Imc Case - Group 3Документ5 страницImc Case - Group 3Shubham Jakhmola100% (3)

- The Future of Psychology Practice and Science PDFДокумент15 страницThe Future of Psychology Practice and Science PDFPaulo César MesaОценок пока нет

- User Manual For Inquisit's Attentional Network TaskДокумент5 страницUser Manual For Inquisit's Attentional Network TaskPiyush ParimooОценок пока нет

- Reproductive Health and Women Constructive Workers: Ruhi GuptaДокумент4 страницыReproductive Health and Women Constructive Workers: Ruhi GuptainventionjournalsОценок пока нет

- 2011 Garg IndiaMovesTowards 732Документ8 страниц2011 Garg IndiaMovesTowards 732smartchinu6Оценок пока нет

- Sree Female Foeticide PDFДокумент73 страницыSree Female Foeticide PDFsreelakshmiОценок пока нет

- Reproductive Health: Women's Well-Being and Reproductive Health in Indian Mining Community: Need For EmpowermentДокумент21 страницаReproductive Health: Women's Well-Being and Reproductive Health in Indian Mining Community: Need For EmpowermentRista Ria PuspitaОценок пока нет

- Domestic ViolenceДокумент19 страницDomestic ViolenceGustavo Enrique Tovar RamosОценок пока нет

- Barat Daya NigeriaДокумент13 страницBarat Daya NigeriaHelni AnggrainiОценок пока нет

- Women With DisabilitiesДокумент14 страницWomen With DisabilitiesSu GarcíaОценок пока нет

- Manuscript PDFДокумент20 страницManuscript PDFHasan MahmoodОценок пока нет

- Perception of Women With Infertiity On Stigma and Disability 2014Документ15 страницPerception of Women With Infertiity On Stigma and Disability 2014Valéria MarquesОценок пока нет

- Gender Disc.Документ15 страницGender Disc.Fun BazzОценок пока нет

- Maternal Mortality in India-NewДокумент17 страницMaternal Mortality in India-NewMaitreyi MenonОценок пока нет

- Vol.3.Issue2 - .Ehsan Nisa Niaz Psychological and Health IssuesДокумент5 страницVol.3.Issue2 - .Ehsan Nisa Niaz Psychological and Health IssuesRabab AbbasОценок пока нет

- A Holistic Approach To Population Control in IndiaДокумент3 страницыA Holistic Approach To Population Control in IndiaOscar Alejandro Cardenas QuinteroОценок пока нет

- "Access To Health Care Service and Gender in India": Submitted byДокумент10 страниц"Access To Health Care Service and Gender in India": Submitted byKashish ChhabraОценок пока нет

- Systems Perspective Understanding Care Giving of The Elderly in IndiaДокумент16 страницSystems Perspective Understanding Care Giving of The Elderly in IndiaUpasana SinghОценок пока нет

- Research Practices Assignment 2.0Документ17 страницResearch Practices Assignment 2.0nancy tsuroОценок пока нет

- Student's Perception Towards Teenage PregnancyДокумент8 страницStudent's Perception Towards Teenage PregnancyKris Mea Mondelo Maca50% (2)

- Fielding Miller2020Документ13 страницFielding Miller2020ucan fajrinОценок пока нет

- Art:10.1007/s12646 013 0198 6Документ8 страницArt:10.1007/s12646 013 0198 6Shilpa Asopa JainОценок пока нет

- 3.isca Irjss 2013 135 PDFДокумент5 страниц3.isca Irjss 2013 135 PDFAnonymous Gj4wl21SNОценок пока нет

- Mothers Autonomy and Childhood StuntingДокумент9 страницMothers Autonomy and Childhood StuntingCawee CawОценок пока нет

- Healthcare Strategies and Planning for Social Inclusion and Development: Volume 2: Social, Economic, and Health Disparities of Rural WomenОт EverandHealthcare Strategies and Planning for Social Inclusion and Development: Volume 2: Social, Economic, and Health Disparities of Rural WomenОценок пока нет

- Catherine ProposalДокумент10 страницCatherine ProposalAlphajor JallohОценок пока нет

- Discrimination Against Girl Child in Rural Haryana, India: From Conception Through ChildhoodДокумент20 страницDiscrimination Against Girl Child in Rural Haryana, India: From Conception Through Childhoodpunjabi songsОценок пока нет

- JLS 10 01 081 18 186 Bhattacherjee C TX (9) .PMDДокумент7 страницJLS 10 01 081 18 186 Bhattacherjee C TX (9) .PMDChitradip BhattacherjeeОценок пока нет

- State Level AnalysisДокумент14 страницState Level AnalysisBere CanelaОценок пока нет

- Hum - Gender Inequality and Health of Women Some Socio-Cultural IssuesДокумент6 страницHum - Gender Inequality and Health of Women Some Socio-Cultural IssuesImpact JournalsОценок пока нет

- Ali Et Al, 2011 Gender Roles and Their Influence On Life Prospects For Women in Urban Karachi PakistanДокумент10 страницAli Et Al, 2011 Gender Roles and Their Influence On Life Prospects For Women in Urban Karachi PakistanAyesha BanoОценок пока нет

- Reproductive Health Status of Rural Scheduled Caste Women of Uttar PradeshДокумент7 страницReproductive Health Status of Rural Scheduled Caste Women of Uttar PradeshMariaОценок пока нет

- Abuse During Childbirth - WikipediaДокумент4 страницыAbuse During Childbirth - WikipediaSiti MuhammadОценок пока нет

- Gender HealthДокумент7 страницGender Healthneelam handikherkarОценок пока нет

- Gift 935 AsignmentДокумент11 страницGift 935 Asignmenttaizya cОценок пока нет

- Reproductive Health of Poor Urban Women in Indore - Rahul BanerjeeДокумент6 страницReproductive Health of Poor Urban Women in Indore - Rahul Banerjeerahul banerjeeОценок пока нет

- Inequity in India: The Case of Maternal and Reproductive HealthДокумент31 страницаInequity in India: The Case of Maternal and Reproductive HealthkavalapparaОценок пока нет

- La IndiaДокумент27 страницLa IndiaJuliana CoockОценок пока нет

- Women Empowerment: Issues and Challenges: Srinivasa Murthy A TДокумент16 страницWomen Empowerment: Issues and Challenges: Srinivasa Murthy A TNaeem Ahmed HattarОценок пока нет

- Status of WomenДокумент24 страницыStatus of WomenShruti AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Sex Education Perception of Teacher Trainees In Uttar Pradesh (India)От EverandSex Education Perception of Teacher Trainees In Uttar Pradesh (India)Оценок пока нет

- Child Sexual Abusein India Carsonetalarticlein Psychological Studies 2013Документ9 страницChild Sexual Abusein India Carsonetalarticlein Psychological Studies 2013Amit RawlaniОценок пока нет

- Final ThesisДокумент118 страницFinal ThesisKyle DionisioОценок пока нет

- Inequity in India: The Case of Maternal and Reproductive HealthДокумент31 страницаInequity in India: The Case of Maternal and Reproductive HealthPankaj PatilОценок пока нет

- FSG Menstrual Health Landscape - India PDFДокумент29 страницFSG Menstrual Health Landscape - India PDFTanya SinghОценок пока нет

- ProposalДокумент13 страницProposalVicky structОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting Contraception Among Women in A Minority Community in Delhi: A Qualitative StudyДокумент6 страницFactors Affecting Contraception Among Women in A Minority Community in Delhi: A Qualitative StudyNur Syamsiah MОценок пока нет

- Sociology P6 U3Документ12 страницSociology P6 U3crmОценок пока нет

- Unit 2 GenderДокумент21 страницаUnit 2 GenderBunmi ChirdanОценок пока нет

- Research Paper Reproductive HealthДокумент11 страницResearch Paper Reproductive Healthapi-613297004Оценок пока нет

- Infertility Social CulturalinfluenceДокумент7 страницInfertility Social Culturalinfluencev menonОценок пока нет

- Devadharshini HareshukeshaДокумент18 страницDevadharshini HareshukeshaDEVADHARSHINI SELVARAJОценок пока нет

- The Psychological Well-Being and Prenatal Bonding of Gestational SurrogatesДокумент8 страницThe Psychological Well-Being and Prenatal Bonding of Gestational SurrogatesAneley FerreyraОценок пока нет

- Health 405 Research Paper 2Документ9 страницHealth 405 Research Paper 2api-549828920Оценок пока нет

- Willie & Callands - 2018 - Reproductive Coercion and Prenatal Distress Among Young Pregnant Women in Monrovia, LiberiaДокумент8 страницWillie & Callands - 2018 - Reproductive Coercion and Prenatal Distress Among Young Pregnant Women in Monrovia, LiberiaHerbert AmbesiОценок пока нет

- Ibarra-Nava2020 Article DesireToDelayTheFirstChildbirtДокумент10 страницIbarra-Nava2020 Article DesireToDelayTheFirstChildbirtAyu MetaОценок пока нет

- Social Determinants of Maternal Health: A Scoping Review of Factors Influencing Maternal Mortality and Maternal Health Service Use in IndiaДокумент24 страницыSocial Determinants of Maternal Health: A Scoping Review of Factors Influencing Maternal Mortality and Maternal Health Service Use in IndiaBaiq RianaОценок пока нет

- Gender Discrimination and Women's Development in India: November 2008Документ16 страницGender Discrimination and Women's Development in India: November 2008Jack NilsonОценок пока нет

- Cooper - Domestic Violence & Pregnancy - A Literature Review PDFДокумент5 страницCooper - Domestic Violence & Pregnancy - A Literature Review PDFpoetry2proseОценок пока нет

- FMSC Global Health Issue PaperДокумент12 страницFMSC Global Health Issue Paperapi-549315638Оценок пока нет

- Chapter IДокумент38 страницChapter ILouresa Mae TОценок пока нет

- Teenage PregnancyДокумент22 страницыTeenage PregnancyIdenyi Juliet EbereОценок пока нет

- From Breast Is BestДокумент23 страницыFrom Breast Is BestTreyОценок пока нет

- English Ethical Issues in Obstetrics and GynecologyДокумент148 страницEnglish Ethical Issues in Obstetrics and Gynecologyquinhox100% (1)

- Parent Child Bed SharingДокумент24 страницыParent Child Bed SharingquinhoxОценок пока нет

- Definitions Matter If Maternal Fetal Relationships Are Not Attachment What Are TheyДокумент3 страницыDefinitions Matter If Maternal Fetal Relationships Are Not Attachment What Are TheyquinhoxОценок пока нет

- Co Sleeping and Acient PracticeДокумент11 страницCo Sleeping and Acient PracticequinhoxОценок пока нет

- Pictorial Representation of Attachment MeasureДокумент9 страницPictorial Representation of Attachment MeasurequinhoxОценок пока нет

- Anxiety in ChildrenДокумент18 страницAnxiety in ChildrenquinhoxОценок пока нет

- New Places of Remeberrance Individual Web Memorials in The NetherlandsДокумент12 страницNew Places of Remeberrance Individual Web Memorials in The NetherlandsquinhoxОценок пока нет

- BCG-How To Address HR Challenges in Recession PDFДокумент16 страницBCG-How To Address HR Challenges in Recession PDFAnkit SinghalОценок пока нет

- Catalogue 2021Документ12 страницCatalogue 2021vatsala36743Оценок пока нет

- Thomas HobbesДокумент3 страницыThomas HobbesatlizanОценок пока нет

- PLSQL Day 1Документ12 страницPLSQL Day 1rambabuОценок пока нет

- Item AnalysisДокумент7 страницItem AnalysisJeff LestinoОценок пока нет

- Ra 7877Документ16 страницRa 7877Anonymous FExJPnCОценок пока нет

- Photo Essay (Lyka)Документ2 страницыPhoto Essay (Lyka)Lyka LadonОценок пока нет

- Chemistry InvestigatoryДокумент16 страницChemistry InvestigatoryVedant LadheОценок пока нет

- 5g-core-guide-building-a-new-world Переход от лте к 5г английскийДокумент13 страниц5g-core-guide-building-a-new-world Переход от лте к 5г английскийmashaОценок пока нет

- Financial Performance Report General Tyres and Rubber Company-FinalДокумент29 страницFinancial Performance Report General Tyres and Rubber Company-FinalKabeer QureshiОценок пока нет

- Iii. The Impact of Information Technology: Successful Communication - Key Points To RememberДокумент7 страницIii. The Impact of Information Technology: Successful Communication - Key Points To Remembermariami bubuОценок пока нет

- Assignment 2 Malaysian StudiesДокумент4 страницыAssignment 2 Malaysian StudiesPenny PunОценок пока нет

- PsychometricsДокумент4 страницыPsychometricsCor Villanueva33% (3)

- AMUL'S Every Function Involves Huge Human ResourcesДокумент3 страницыAMUL'S Every Function Involves Huge Human ResourcesRitu RajОценок пока нет

- Applications of Tensor Functions in Solid MechanicsДокумент303 страницыApplications of Tensor Functions in Solid Mechanicsking sunОценок пока нет

- Brahm Dutt v. UoiДокумент3 страницыBrahm Dutt v. Uoiswati mohapatraОценок пока нет

- Topic 6Документ6 страницTopic 6Conchito Galan Jr IIОценок пока нет

- Diva Arbitrage Fund PresentationДокумент65 страницDiva Arbitrage Fund Presentationchuff6675Оценок пока нет

- Science Technology and SocietyДокумент46 страницScience Technology and SocietyCharles Elquime GalaponОценок пока нет

- Chapter 6 Bone Tissue 2304Документ37 страницChapter 6 Bone Tissue 2304Sav Oli100% (1)

- Parts Catalog: TJ053E-AS50Документ14 страницParts Catalog: TJ053E-AS50Andre FilipeОценок пока нет

- Literatures of The World: Readings For Week 4 in LIT 121Документ11 страницLiteratures of The World: Readings For Week 4 in LIT 121April AcompaniadoОценок пока нет

- Sabbir 47MДокумент25 страницSabbir 47MMd.sabbir Hossen875Оценок пока нет

- MGT 601-Smes Management MCQ For Final Term Preparation: ProductionДокумент80 страницMGT 601-Smes Management MCQ For Final Term Preparation: ProductionSajidmehsudОценок пока нет

- Cryptography Practical 1Документ41 страницаCryptography Practical 1Harsha GangwaniОценок пока нет

- Ob AssignmntДокумент4 страницыOb AssignmntOwais AliОценок пока нет