Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Justice

Загружено:

LawtenderАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Justice

Загружено:

LawtenderАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.

txt

unknown

Seq: 1

6-NOV-15

8:46

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY

LAW REVIEW

VOLUME 90

NOVEMBER 2015

NUMBER 5

BRENNAN LECTURE

ACCESS TO JUSTICE:

NEW APPROACHES TO ENSURE

MEANINGFUL PARTICIPATION

THE HONORABLE CHASE T. ROGERS*

This Lecture discusses innovative approaches that courts are employing and developing to ensure that all participants in court proceedings have meaningful access to

justice. Approaches include making the most of technological advancements to provide electronic access to information and to promote an understanding of the legal

process, working with the legal community to provide representation to selfrepresented parties, and examining the legal process in order to simplify procedures, better manage cases, control costs, and provide workable alternatives to

traditional methods for resolving disputes.

* Copyright 2015 by Chase T. Rogers, Chief Justice, Connecticut Supreme Court.

An earlier version of this lecture was delivered as the 21st Justice William J. Brennan Jr.

Lecture on State Courts and Social Justice at the New York University School of Law on

February 25, 2015. Many of the observations in this Lecture about the functioning of the

legal system and its processes are drawn from my years of experience, both in private

practice and in the judiciary. From 1991 to 1998, I was a partner at Cummings &

Lockwood, where I specialized in commercial and employment litigation. In 1998, I was

nominated to serve on the Connecticut Superior Court. Between 2001 and 2005, I was

assigned to the Complex Litigation Docket in Stamford, and from 2005 to 2006, I served as

the presiding judge for civil matters in the Stamford-Norwalk Judicial District. In 2006, I

was sworn in as an Appellate Court judge; a year later, I was sworn in as the Chief Justice

of the Connecticut Supreme Court. I am currently a member of a variety of commissions

and boards, including the National Center for State Courts Expanding Court Access to

Justice Project Advisory Committee and the Conference of Chief Justices Civil Justice

Initiative Committee. To the extent that this Lecture includes unfootnoted assertions,

please treat them as my personal beliefs and views and weight them accordingly.

1447

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

1448

unknown

Seq: 2

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW

6-NOV-15

8:46

[Vol. 90:1447

I. ACCESS TO JUSTICE: CHALLENGES AND

OPPORTUNITIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

II. MANAGERIAL JUDGING IN THE TWENTY-FIRST

CENTURY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A. Aligning Judicial Resources with Case Needs . . . . . . . .

B. Improving Specific Case Management Practices . . . . .

C. Providing Justice for Self-Represented Parties . . . . . . .

III. CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1448

1452

1452

1456

1459

1462

Good evening. Let me begin by saying what a tremendous honor

it is to have been asked to deliver the 21st Annual William J. Brennan

Jr. Lecture on State Courts and Social Justice. I am well aware of both

the intellect and innovation that my predecessors in giving this lecture

have brought to the table, and my goal this evening is to push the

boundaries and provoke at least some percentage of the thought and

dialogue stemming from those lectures. This may be particularly

difficult given that last years Brennan Lecturer, Chief Judge Jonathan

Lippman of the New York Court of Appeals, represents probably the

most progressive thinker in the area of administrative reform in the

court system.1 He has set the bar very high but I will do my best.

I would submit to you that our historical approach to access-tojustice issues must dramatically change if we are to continue to make

advancements in this area. Although past efforts were mainly limited

to educating self-represented parties about the court system, future

efforts must go further to strengthen our commitment to fair

representation for all parties involved in legal proceedings. In this

regard, I am going to limit my remarks to procedures in the civil

justice system and not wade into the waters of criminal justice, a field

presenting its own unique challenges.

ACCESS

TO

I

JUSTICE: CHALLENGES

AND

OPPORTUNITIES

In beginning this discussion, I want to emphasize that we are not

talking about access for accesss sake; instead, it is essential to provide

a pathway for people where we can assure that justice is being

achieved and not falling by the wayside because someone does not

speak English, does not know what papers to file, does not know what

arguments to make, or simply does not understand the purpose of the

hearing. Our ability to ensure timely access to justice is undoubtedly

1 For a discussion of the role of the judiciary in promoting access-to-justice reforms,

see Jonathan Lippman, The Judiciary as the Leader of the Access-to-Justice Revolution, 89

N.Y.U. L. REV. 1569 (2014).

R

R

R

R

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

November 2015]

unknown

BRENNAN LECTURE

Seq: 3

6-NOV-15

8:46

1449

affected by the remarkable changes that have occurred in our courts

and our society, more generallysince my generation of lawyers

graduated from law school.

The first change is advancement in technology. As we know,

people in the United States are plugged in and expect to do much of

their business, including court business, through computers and the

web.2 It was approximately ten years ago that some states began

implementing e-filing of court documents.3 For instance, civil and

family case filings in Connecticut are e-filed and our judges issue their

rulings electronically for the majority of cases.4 Throughout the

country, judicial websites include databases with online case lookup

and a whole menu of information, including forms and tutorials in

multiple languages.5 In the past, people had to go to courthouses to

access this information, where in all likelihood the only language

2 See generally PAUL H. ANDERSON, NATL CTR. FOR STATE COURTS, FUTURE

TRENDS IN PUBLIC ACCESS: COURT INFORMATION, PRIVACY, AND TECHNOLOGY 11 (2011),

available at http://www.ncsc.org/~/media/Microsites/Files/Future%20Trends/Author

%20PDFs/Anderson.ashx (discussing a variety of court transactions conducted

electronically and noting that the public not only expects easy access to information, but

also expects it to be instantaneous, wherever one is located). A recent survey found that

around three-fourths of respondents would definitely or probably use online services to

access court records, pay fines or fees, or submit procedural questions to court staff, if

available. NATL CTR. FOR STATE COURTS, THE STATE OF STATE COURTS: 2014 POLL 10

fig.6 (2014) [hereinafter THE STATE OF STATE COURTS: 2014 POLL], available at http://www

.ncsc.org/~/media/Files/PDF/Topics/Public%20Trust%20and%20Confidence/2014-State-ofState-Courts-Survey-Presentation-12042014.ashx.

3 See Christopher G. Blake, State Judicial Branch to Launch E-filing, CONN. LAWYER,

Mar. 2004, at 2, 2 (noting that the Connecticut Judicial Branch launched an e-filing

platform in 2004, joining at least nineteen other states and the District of Columbia, which

had already implemented some version of a comparable system); see also John T. Matthias,

E-Filing Expansion in State, Local, and Federal Courts 2007, in FUTURE TRENDS IN STATE

COURTS 2007, at 34, 34 (Carol R. Flango et al. eds., 2007), available at http://

cdm16501.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/tech/id/570/ (claiming that twenty-six

states have adopted court rules enabling e-filing statewide or in at least one court).

4 In Connecticut, where electronic filing is mandatory for most civil matters and for

many family matters, the public has nearly instantaneous electronic access to documents

and to orders in civil cases. See CONN. JUDICIAL BRANCH, CIVIL AND FAMILY E-FILING

MANUAL: A GUIDE FOR ATTORNEYS AND LAW FIRMS (2014), available at http://

www.jud.ct.gov/external/super/e-services/efile/Atty_UserManual.pdf (instructing selfrepresented parties and attorneys on how to access a variety of judicial services). In family

cases, attorneys or self-represented parties who have an appearance in a case can now view

orders and most filings in that case online. CONN. JUDICIAL BRANCH, FREQUENTLY ASKED

QUESTIONS ABOUT E-FILING (2015), available at http://www.jud.ct.gov/external/super/eservices/efile/SRP_FAQs.pdf; CONN. JUDICIAL BRANCH, FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

ABOUT E-FILING (2015), available at http://www.jud.ct.gov/external/super/e-services/efile/

ATTY_FAQs.pdf.

5 On the Connecticut Judicial Branch Website, for example, members of the public

may download forms, search to find information about a case or appeal, view videos on a

variety of topics, or participate in tutorials on how to perform numerous tasks. Self-Help

Section, CONN. JUD. BRANCH, http://jud.ct.gov/selfhelp.htm (last visited June 27, 2015).

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

1450

unknown

Seq: 4

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW

6-NOV-15

8:46

[Vol. 90:1447

spoken by judicial staff was English. Now technology has provided us

with the ability to communicate in approximately 170 languages

through the use of LanguageLine, either by phone or in person.6 In

addition to implementing a pilot program to provide translation services, the use of videoconferencing in Connecticut has increased

during the past several years, ensuring access for individuals who

might find it difficult to attend court proceedings in person. Similarly,

attorneys and self-represented parties have access to a variety of

research materials online, making it possible for them to prepare for

court even if they do not have access to a nearby law library or courthouse7 All of these technological changes have created efficiencies

and exciting opportunities for the administration of justice that I will

later discuss.

Turning to the second major change: The societal environment in

which we live has also changed dramatically. Specifically, we have witnessed a large and growing economic gap in this country,8 which has

made it more difficult for people to afford legal representation and

has also caused an increase in the number of foreclosure and debt

collection actions.9

This economic gap is partially responsible for the final major

change in our court system that I will focus onnamely, there are

more self-represented parties in our courts, from California to

Connecticut, than ever before. People are representing themselves in

family and civil matters in astonishing numbers.10 Just looking at

Connecticut in family cases, 85% of the cases have at least one party

6 See James E. Cabral et al., Using Technology to Enhance Access to Justice, 26 HARV.

J.L. & TECH. 241 (2012), for an extensive discussion of the variety of ways in which

technology is being used to improve access to justice.

7 See Quick Links, CONN. JUD. BRANCH LAW LIBR., http://jud.ct.gov/lawlib/ (last

visited June 27, 2015) (providing visitors with links to access a variety of legal resources).

8 See Richard Fry & Rakesh Kochhar, Americas Wealth Gap Between Middle-Income

and Upper-Income Families Is Widest on Record, PEW RES. CTR. (Dec. 17, 2014), http://

pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/2017/wealth-gap-upper-middle-income/ (describing record

levels of economic inequality by a number of metrics).

9 See SONCIA COLEMAN ET AL., CONNECTICUT GENERAL ASSEMBLY, OFFICE OF

LEGISLATIVE RESEARCH, 2010-R-0019, EFFECTS OF FORECLOSURE CRISIS IN

CONNECTICUT 1 (2010), available at http://www.cga.ct.gov/2010/rpt/2010-R-0019.htm

(discussing foreclosures in Connecticut).

10 See LEGAL SERVICES CORPORATION, DOCUMENTING THE JUSTICE GAP IN AMERICA:

THE CURRENT UNMET CIVIL LEGAL NEEDS OF LOW-INCOME AMERICANS 25 (2009),

available at http://www.lsc.gov/sites/default/files/LSC/pdfs/documenting_the_justice_gap_in

_america_2009.pdf (Although there is no national compilation of statistics on

unrepresented litigants in court, data from some court systems shows extremely high

numbers, often clustered in those courts in which low-income people are particularly likely

to appear, such as family and housing courts . . . .). Data from 2006 indicates, for example,

that 70% of litigants in family cases in Wisconsin were unrepresented, that at least one

party was self-represented in as many as 80% of family cases in Massachusetts, and that

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

November 2015]

unknown

BRENNAN LECTURE

Seq: 5

6-NOV-15

8:46

1451

who is self-represented and, even more surprisingly, approximately

25% of civil cases have at least one self-represented party, which is

almost always the defendant.11 Perhaps most shockingly, at the intermediate Appellate Court approximately 39% of the cases have one

self-represented party.12 Ladies and gentlemen, this would have been

unheard of when I graduated from law school.

We know, however, that if we are to sustain public confidence in

the justice system and rule of law, we must provide meaningful access

to justice for everyone, including people representing themselves. On

the national level, it appears that many litigants represent themselves

in court not because they choose to, but because they cannot afford an

attorney.13 Equally troubling, studies suggest that this lack of representation has a negative impact on both the litigants and the courts.14

So, how do we ensure continued meaningful access to justice for

all amid these many changes? How do we effectively and efficiently

continue to meet our obligation under the social compact we have

with the people we serve, so we maintain their support, as a branch of

a democratic government? The answer, I would submit, is this: We

need to change the mindset that has defined, for centuries, the process

by which we handle civil cases.

When my contemporaries and I went to law school, all of our

training was in the context of an advocacy system that culminated in a

trial.15 The key players always included two attorneys, one per party,

and a judge, regardless of the complexity or the merits of the case. The

essential feature of the court system wasand remainsa one-size67% of petitioners and 80% of respondents in family cases in California were

unrepresented. Id.

11 CONN. JUDICIAL BRANCH, SELF-REPRESENTED PLAINTIFFS AND DEFENDANTS IN

ALL FAMILY CASE TYPES BY STATE FISCAL YEAR (2014) (on file with the New York

University Law Review); CONN. JUDICIAL BRANCH, SELF-REPRESENTED PLAINTIFFS AND

DEFENDANTS IN ALL CIVIL CASE TYPES BY STATE FISCAL YEAR (2014) (on file with the

New York University Law Review).

12 CONN. JUDICIAL BRANCH, KEEPING COURTS RELEVANT IN A CHANGING SOCIETY:

BIENNIAL REPORT AND STATISTICS 20122014, at 45 (2015) [hereinafter BIENNIAL

REPORT], available at http://jud.ct.gov/Publications/es191.pdf (counting 1157 appeals filed

in the Appellate Court during fiscal year 2014, of which 457 had at least one selfrepresented party according to an internal report generated in July 2015).

13 LEGAL SERVICES CORPORATION, supra note 10, at 23 (Based on their own

observations and currently available data, many judges, court administrators, members of

the legal aid community, and commentators have raised concerns about unrepresented

litigants, arguing that most people who appear in court without an attorney do so because

they cannot afford one . . . .).

14 Id. at 26.

15 See U.S. DEPT OF JUSTICE, NCJ 223851, CIVIL BENCH AND JURY TRIALS IN STATE

COURTS, 2005, at 1 (2009), available at http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cbjtsc05.pdf

(In the nations 75 most populous counties, the number of general civil cases disposed of

by jury or bench trial declined by about 50% from 1992 to 2005.).

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

1452

unknown

Seq: 6

6-NOV-15

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW

8:46

[Vol. 90:1447

fits-all approach to disposing of cases. This approach, I argue, is completely ill-suited in the twenty-first century. Put another way: The

foundations of the court system and the processes by which claims are

resolved are outdated and require serious rethinking.

II

MANAGERIAL JUDGING

IN THE

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

I am pleased to report that this discussion is well underway at the

national level. Chief Justices from all the states meet regularly to discuss issues of mutual concern and to provide education regarding possible solutions.16 In 2013, the Conference of Chief Justices passed a

resolution creating a national committee to focus on civil justice.17 As

a member of the Civil Justice Initiative Committee, I can tell you that

we have been hard at work over the past year to identify common

issues, best practices, and new ways to provide timely and costefficient resolutions to civil cases. It has been an exciting project

funded by the National Center for State Courts and the State Justice

Institute, and we have been working under the able leadership of

Oregon Chief Justice Thomas Balmer.18 Based on our progress to

date, I am absolutely certain the Committees final product will be

useful in our individual states as we all look for ways to improve our

civil justice system.

A. Aligning Judicial Resources with Case Needs

The first important change is for court systems to shift their focus

and recognize that expediency is not the only goal. Rather, we must

also take some responsibility for helping to reduce the amount of

money it takes to resolve a civil or family case. The added benefit of

reducing costs is that litigants are more likely to hire legal counsel for

at least a part of their court matter when the prospective costs are

lower. At the same time, we must also recognize that some people will

continue to represent themselves in court proceedings, and we must

do everything we can to ensure just outcomes in their cases.

16 See CONFERENCE OF CHIEF JUSTICES, THE HISTORY OF THE CONFERENCE OF CHIEF

JUSTICES 7284 (2009), available at http://ccj.ncsc.org/~/media/Microsites/Files/CCJ/Web%

20Documents/CCJ%20History%2061709.ashx (listing topics of discussion at annual and

midyear meetings of the Conference of Chief Justices since 1949).

17 CONFERENCE OF CHIEF JUSTICES, RESOLUTION 5: TO ESTABLISH A COMMITTEE

CHARGED WITH DEVELOPING GUIDELINES AND BEST PRACTICES FOR CIVIL LITIGATION

(2013), available at http://ccj.ncsc.org/~/media/microsites/files/ccj/resolutions/01302013civil-litigation-establish-committee-charged-with-developing-guidelines.ashx.

18 Committees, CONFERENCE OF CHIEF JUSTICES, http://ccj.ncsc.org/Committees.aspx

(last visited June 27, 2015).

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

November 2015]

unknown

Seq: 7

BRENNAN LECTURE

6-NOV-15

8:46

1453

There is no question that the bar must find ways to reduce the

costs of representation. In fact, the National Center for State Courts

recently conducted a survey finding that people perceived the cost of

hiring an attorney to be the greatest barrier to accessing justice.19

Having listened to the current ABA president, Bill Hubbard, recently

speak, I can tell you that bar leadership is also trying to reduce costs

to ensure representation for litigants and sustainable legal practices

for their attorneys. Although we look forward to seeing the bars

approach to this problem, we in the judicial system must also help find

an affordable solution. Seeking techniques to make the process less

expensive, therefore, has been a recurring theme in the Committees

discussions.

So how do we reduce cost? Consider the following scenario: You

are one of the most experienced judges in a civil courtroom in your

state. Half of your day is spent on handling discovery motions on a

docket consisting of slip-and-fall or minor motor-vehicle cases. You

have several more complicated cases in the mix, including a complex

commercial matter with a motion for summary judgment, that must all

wait until you get through the morning docket. As the day wears on,

somewhere amid the myriad cases before you, you think: Is this

really an efficient use of judicial resourcesnot to mention the party

resources expended on attorneys fees or opportunity costs incurred

waiting for an argument regarding discovery?

We are finally starting to recognize that one size no longer fits all.

Cases involving numerous parties, extensive discovery, a significant

number of motions, complex issues, and numerous witnesses require

more time and resources than those involving limited numbers of parties, minimal discovery, few motions, simpler issues, and one or two

witnesses. We need to find a way to distinguish straightforward cases

in civil court from those requiring more judicial involvement so we

can efficiently allocate resources. Of course, I am not suggesting some

cases are unimportant; we all know that parties consider their cases

very important, regardless of the circumstances. Yet when it comes to

managing a docket, it is important to categorize which cases require

substantial judicial oversight and time, and which ones require less. If

we are simply processing a docket, rather than managing it, we run the

risk of costly outcomes that may also take too long to resolve. We also

run the risk that the resources and effort invested in a case are not

proportional to the damages at stake.

The Civil Justice Initiative Committee is operating from the same

premise as our hypothetical judge sitting on the bench worrying about

19

THE STATE

OF

STATE COURTS: 2014 POLL, supra note 2, at 16 fig.11.

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

1454

unknown

Seq: 8

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW

6-NOV-15

8:46

[Vol. 90:1447

the necessity to oversee certain stages of the judicial process in certain

types of cases. Essentially, we are talking about aligning our judicial

resources so that a civil case may be handled in the most cost-efficient

manner, from the moment of filing all the way through resolution. Not

only would these efficiency measures benefit the litigants by saving

them time and money, but they would also benefit the courts, which

have limited resources.

In this regard, the Committee has been looking at developing a

system that segregates cases into three different pathways, each with a

process tailored to reach an efficient resolution of its type of matter.

This approach proceeds from a simple and uncontroversial premise:

Not all cases require the same level of discovery and judicial management. In a simple debt collection matter, for example, why require

that parties follow procedures in place to govern discovery, depositions, expert witnesses, and motions practice in complex cases like

medical malpractice suits? It really does not make any sense and consequentially results in increased costs for the parties.

This three-pathway approach can be characterized by streamlined, standard, and complex tiers. Although the details defining this

approach are not yet fully developed, the basic premise is established:

When a case is initially filed it should be categorized, by case type,

into one of the three tiers. A party may file a motion to be removed

and relocated in a different tier. As we proceed in developing this

idea, some of the questions necessitating consideration include what

criteria should be used to slot cases, what role the parties and the

courts should play in the process, what procedures should apply to

different pathways, and whether cases should be reassessed periodically to determine whether they have been assigned properly.

Streamlined cases would require little judicial oversight, which,

by way of example, may include slip-and-falls, debt collections, and

small claims appeals. Here, the intent is to institute different procedures for these cases, so as to limit judicial involvement and discovery.

As a result, the system could resolve cases efficiently and at minimal

cost within a predefined period of time. For instance, there could be

mandatory and limited discovery that would be exchanged almost

immediately. There may also be simpler rules and less time contemplated for resolution of these types of matters including limited trial

length. Interestingly, a majority of the cases we handle fall within this

category20 and many of these cases involve people who represent

20 Between the 200607 and 201011 fiscal years, the number of contract collection

cases doubled. Contract collection and foreclosure cases accounted for approximately 55%

of pending civil cases in Connecticut in fiscal year 201011. CONN. JUDICIAL BRANCH,

COMMISSION ON CIVIL COURT ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION: REPORT AND

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

November 2015]

unknown

BRENNAN LECTURE

Seq: 9

6-NOV-15

8:46

1455

themselves. A simpler process with less motion practice can only

improve access and our corresponding ability to provide justice.21

The second group, which has been described as the standard

pathway, involves all the cases falling between streamlined and complex. To some extent, this is a catch-all group. These are the cases

that require some regular judicial management and oversight but do

not rise to the level of a complex case, in which discovery and judicial

involvement is extensive. Again, we anticipate recommending

mandatory disclosure of all relevant evidence proportional to the case

and early judicial involvement to set up a schedule including a firm

trial date to take place within approximately twelve months of filing.

Courts may intelligently use technology, such as videoconferences or

phone calls, to handle matters that arise. For example, a judge may

require such a conference to preview whether a discovery dispute

should be formally filed in writing or can be resolved, instead, by conference. Although far more controversial, we are also considering

whether judges may want to preview by conference whether a summary judgment motion should be filed at all.

As I have already mentioned, the last category would be complex

cases, such as those involving complicated issues, multiple litigants,

and/or demands for significant damages, that are labor intensive for

judges, court staff, and the parties. These cases generally involve more

discovery, more complicated legal issues, and more regular involvement by a single judge who is familiar with the discovery and legal

issues in a particular matter. Fortunately, a number of states have

extensive experience with this category of cases because they have

already carved out complex litigation dockets.

The overarching goal for the three-pathway approach is to

manage the process so that the court can give each case sufficient time

and attention to ensure fair handling without giving each case more

RECOMMENDATIONS 6 (2011) [hereinafter ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION], available

at https://www.jud.ct.gov/Committees/ADR/Commission_Final_Report_122111.pdf; see

also Paula Hannaford-Agor, Measuring the Cost of Civil Litigation: Findings from a Survey

of Trial Lawyers, VOIR DIRE, Spring 2013, at 22, 28 n.2, available at http://ccj.ncsc.org/~/

media/Files/PDF/Services%20and%20Experts/Areas%20of%20expertise/Civil%20Justice/

Measuring-cost-civil-litigation.ashx (Although many other categories of civil cases

including products liability, intellectual property, defamation (libel/slander) are cited as

some of the most time-consuming and expensive types of civil litigation, individually they

comprise a very small proportion of civil cases.).

21 See, e.g., Thomas M. Clarke & Victor E. Flango, Case Triage for the 21st Century, in

FUTURE TRENDS IN STATE COURTS 2011, at 146, 148 (Carol R. Flango et al. eds., 2011),

available at http://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/ctadmin/id/1847 (The

[Maricopa, Arizona, family] court discovered that about half of all the family cases

required only an entry of decree or judgment by default or consent to dispose, so it . . .

began to offer online decree-on-demand and default-on-demand capabilities.).

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

1456

unknown

Seq: 10

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW

6-NOV-15

8:46

[Vol. 90:1447

time and attention than is required. By setting up these pathways, we

can use judicial resources most effectively, allowing judges to spend

more time on the cases that should actually require more of their time.

This is just common sense in terms of court management, but it is also

a major change that not everyone, including some members of both

the Judicial Branch and the bar, will embrace initially.22 Fortunately,

we have already learned from some states experiences about changes

in procedure that appear to work well and where problems may arise.

For instance, experience suggests that systems such as the threepathway approach should be designed around an opt-out rather than

an opt-in mechanism because concerns about limited discovery make

lawyers reluctant to opt in. We have also found that cases should be

tiered by case type and not by dollar amount because some lawyers

will overstate their damages to avoid limitation in discovery.

B. Improving Specific Case Management Practices

Connecticut is taking additional steps to restructure our civil

system with the goal of providing relevant, affordable, and accessible

service. Based on the results of stakeholder focus groups, we identified four general areas for restructuring: 1) improving litigation management; 2) confronting current discovery issues; 3) enhancing

alternative dispute resolution options; and 4) evaluating the needs and

impact of self-represented parties.

With regard to the first two categories of improving litigation

management and confronting discovery issues, just as we have identified on the national level that we have to manage our dockets differently depending on case type, we learned from focus groups that it is

not just a timely resolution that is important.23 Over the years, we

have made changes that allow virtually any civil matter in the State to

be tried within twelve months. So getting to a resolution is not the

issue for us. Instead, it is essential to examine the entire process of

reaching that timely resolution. The current process results in higher

costs and less confidence in the efficacy and fairness of dispute resolu-

22 See, e.g., Judith Resnik, Managerial Judges, 96 HARV. L. REV. 374, 425, 43245

(1982) (cautioning that transforming judges from adjudicators to managers substantially

expands the opportunities for judges to useor abusetheir power, then suggesting

safeguards to preserve judicial impartiality and discussing alternatives to judicial

management).

23 Internal Report Concerning Second Phase of Strategic Plan drafted by the Conn.

Judicial Branch 3 (2014) [hereinafter Second Phase of Strategic Plan] (on file with the New

York University Law Review).

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

November 2015]

unknown

BRENNAN LECTURE

Seq: 11

6-NOV-15

8:46

1457

tion.24 For example, attorneys in nearly all focus groups expressed

frustration with current discovery rules and practices.25

As a result, national proposals for a three-tier system and the

requirement of automatic and proportional discovery are under

serious consideration in Connecticut. Several other changes are

already underway. For instance, we have begun to implement individual calendaring for most types of cases where one judge is responsible for a case from start to finish instead of multiple judges handling

pretrial matters.26 My guess is that attorneys who practice exclusively

in federal court are surprised to hear that multiple judges may handle

different aspects of a single case. The reality is many states have this

system, mainly because our dockets are so much larger than those of

the federal system. In Connecticut last year we disposed of over onehalf million cases in our trial courts,27 whereas all of the United States

District Courts combined disposed of fewer than 400,000 cases.28

Despite the difficulties in managing such a large docket through individual calendaring, we are excited that this change is occurring in

Connecticut. Individual calendaring should make the process more

efficient for the courts and for the parties because each matter in a

case will be handled by a judge who is already familiar with the facts,

procedural history, and the law in the case as well as the parties. Similarly, the parties are familiar with the judge and his or her methods

and practices. We are confident that this system will enhance the consistency and predictability of rulings on motions and discovery disputes and increase the possibility for settlement.

We also plan to continue to take advantage of technology. For

example, instead of filing and arguing motions, the parties now will be

able to resolve many pleadings and discovery disputes through status

conferences by phone or videoconferencing, saving lawyers and parties a lot of time and money.29

24

Id.

Id. at 16. Attorneys also expressed frustration with: a lack of uniformity with respect

to scheduling of proceedings; the date of jury selection; the way individual voir dire is

conducted; the availability of telephone or video conferencing; and inconsistency that

results when multiple judges are assigned to handle rulings on motions, discovery, and

scheduling in a single case. Id. at 37. In the focus groups, attorneys suggested education

and training for judges and members of the bar in substantive law topics, case

management, and settlement strategies and techniques. Id. at 14.

26 Id. at 710.

27 See BIENNIAL REPORT, supra note 12, at 41, 44 (providing statistics for the year

ending on June 30, 2014).

28 Federal Judicial Caseload Statistics 2014, U.S. COURTS (last visited Sept. 22, 2015),

http://www.uscourts.gov/statistics-reports/federal-judicial-caseload-statistics-2014

(providing statistics for the year ending on March 31, 2014).

29 Second Phase of Strategic Plan, supra note 23, at 7.

25

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

1458

unknown

Seq: 12

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW

6-NOV-15

8:46

[Vol. 90:1447

In addition to changing our pretrial case management, we are

also enhancing our alternative dispute resolution services in the hopes

that we can help individuals settle their differences without the costs

associated with trial. This initiative has actually been in the works in

Connecticut for some time. While the traditional role of the courts is

to resolve disputes through trial, we all know that the vast majority of

cases settle as opposed to being tried to conclusion.30 I, therefore,

believe that if we are to stay relevant, we need to also provide a high

level of alternative dispute resolution.

Not surprisingly, in-house counsel and lawyers are now telling us

that arbitration and private mediation are not the mecca they had

anticipated.31 Instead, they are telling us that arbitration is turning out

to be costly and unpredictable and that private mediation is even

more expensive.32 As a result, they are willing to return to the court

system if they can expect a high level of service. I see this as an opportunity and, in our court system, we have worked to simplify the process of requesting and scheduling a judicial alternative dispute

resolution session in a civil case. We have also increased, statewide,

the number of judges available to mediate cases, and we have ongoing

judges education programs that focus on mediation models, techniques, and strategies to resolve cases through alternative dispute resolution.33 Without highly trained judges, we cannot succeed in this

area, particularly since judicial mediation requires a completely different skillset than presiding over a trial.

We are also looking at the idea of creating an actual mediation

center and docket, which could potentially ensure that effective and

skilled mediation is widely available for all parties, not just those who

can afford private mediation. This center may mirror what is available

in the private sector with, for example, multiple conference rooms and

30 See Presentation Slides of the Connecticut Judicial Branch presented at the

Connecticut Bar Foundations Kravitz Symposium on the Vanishing Trial (Dec. 4, 2012)

(on file with the New York University Law Review) (reporting many more cases are

resolved than actually reach civil judgment, implying a high settlement rate).

31 See, e.g., CORINA D. GERETY & BRITTANY K.T. KAUFFMAN, INSTITUTE FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF THE AMERICAN LEGAL SYSTEM, SUMMARY OF EMPIRICAL RESEARCH

ON THE CIVIL JUSTICE PROCESS: 20082013, at 3435 (2014), available at http://iaals.du

.edu/images/wygwam/documents/publications/Summary_of_Empirical_Research_on_the_

Civil_Justice_Process_2008-2013.pdf (observing a majority of attorneys surveyed view

court-ordered alternative dispute resolution as a positive development for managing

costs, but most would not choose private mediation over litigation, and opinions on

arbitration were mixed).

32 See ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION, supra note 20, at 7071, 89, 9394 (2011)

(polling attorneys and soliciting comments on their participation in alternative dispute

resolution programs).

33 BIENNIAL REPORT, supra note 12, at 23.

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

November 2015]

unknown

Seq: 13

6-NOV-15

BRENNAN LECTURE

8:46

1459

extended hours. The significant difference, of course, is this service

would be free, thereby making it accessible to all.

The need to come up with best practices and dedicated resources

in the area of alternative dispute resolution is again based on a recognition that mediation resolves appropriate cases more efficiently, at an

earlier point in the process, and at considerably less cost to the

parties.34

C. Providing Justice for Self-Represented Parties

Finally, I want to turn to the remaining focus area in Connecticut

and one of the initial major changes I identified for you in the administration of justice: addressing the needs and impact of the everincreasing number of self-represented parties in our court system. This

phenomenon is directly impacting access to justice, and you simply

cannot consider restructuring court processes without considering it.

As stated before, 25% of civil cases in Connecticut have at least

one self-represented party, and this number is 85% in family cases.35

We know that some of them have no choice because the cost of legal

representation is too high.36 We also know that others, who may have

resources to hire an attorney, believe they can navigate the court

system effectively on their own.37 Either way, I would submit to you

that the reason is immaterial. The self-represented population is

increasing, and we must find ways to improve their access to justice

while at the same time remain aware of the impact on judges, court

staff, attorneys, and the entire justice system. In sum, our job is to

offer a fair and efficient forum to all litigants, regardless of whether

they are self-represented or represented by counsel.

To address the needs of self-represented parties, the Connecticut

Judicial Branch for many years has been committed to a variety of

programs and services. Some are focused on helping self-represented

parties navigate the system, and others are geared to identify ways to

find legal representation for them.

By way of just a few examples, with regard to people who cannot

afford an attorney or just decide to go it alone, we have Court Service

Centers and Public Information Desks in almost every judicial dis34 See ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION, supra note 20, at 7 (recommending ADR

program design that treats the litigants fairly and reduces the time it takes to dispose of

cases).

35 See BIENNIAL REPORT, supra note 12 and accompanying text.

36 See THE STATE OF STATE COURTS: 2014 POLL, supra note 2, at 16 (suggesting, on the

basis of a national opinion poll, that the cost of legal representation is the primary factor

keeping potential claims out of court entirely).

37 See LEGAL SERVICES CORPORATION, supra note 10, at 12 (reporting increased

numbers of unrepresented litigants).

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

1460

unknown

Seq: 14

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW

6-NOV-15

8:46

[Vol. 90:1447

trict.38 Not only do these resources provide members of the public

with general information about the court, but they also answer questions about scheduling and deadlines, offer work space and computer

access, provide information to parties about their case files, direct

individuals to additional sources of help and information, and review

papers to ensure that they are complete. In 2014, they provided assistance and services to 348,182 court patrons, including self-represented

parties, attorneys, and other individuals.39 The overarching goal is to

provide information and assistance that lead, ultimately, to a better

understanding of the court system and the proceedings.

In addition, materials and forms on the Judicial Branch website

are revised and simplified on an ongoing basis to include the addition

of Spanish translations as well as employee training to assist court

patrons of limited English proficiency.40 We have also developed

online tutorials and guides to assist self-represented parties in

defending lawsuits and filing appearances.41 These services help, but

we all know that under our current civil system, justice is better served

if people are represented by counsel.42 In this regard, we have worked

with our legal aid community to increase its funding.

We have also concentrated on making partial legal representation

available to those individuals who cannot afford an attorney to handle

all of their case. We recently made it possible for clients to hire attorneys to file limited scope appearances to represent them in at least the

most crucial proceedings in a case.43 For those who cannot afford an

attorney at all, but want some assistance, volunteer attorney programs

in the areas of foreclosure, domestic violence, and family law have

been established.44 With the continued generous cooperation of the

bar, we anticipate expanding these programs.

38 Court Service Centers, CONN. JUD. BRANCH, http://jud.ct.gov/CSC/services.htm (last

visited July 14, 2015); Public Information Desks, CONN. JUD. BRANCH, http://jud.ct.gov/pid/

(last visited July 14, 2015).

39 See Court Service Centers, CONN. JUD. BRANCH, http://jud.ct.gov/CSC/services.htm

(last visited July 14, 2015) (providing information and listing services); Public Information

Desks, CONN. JUD. BRANCH, http://jud.ct.gov/pid/ (last visited July 14, 2015) (same).

40 See generally BIENNIAL REPORT, supra note 27, at 3538 (outlining initiatives in

recent redesigns of the Judicial Branch website).

41 See How Do I?, CONN. JUD. BRANCH, http://jud.ct.gov/howdoi.htm (last visited July

14, 2015) (providing instructions on filing and defending various civil matters).

42 See LEGAL SERVICES CORPORATION, supra note 10, at 12 (reporting research

showing worse legal outcomes for unrepresented litigants).

43 See BIENNIAL REPORT, supra note 27, at 6 (documenting a pilot program which

allows attorneys to agree with clients to represent them only for specific events or

proceedings in family court matters).

44 Id. at 12.

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

November 2015]

unknown

BRENNAN LECTURE

Seq: 15

6-NOV-15

8:46

1461

Additionally, one of the more exciting developments we have

seen is the creation of LawyerCorps Connecticut, which is modeled

roughly on Teach For America. The program was conceived two years

ago as a means of engaging Connecticuts business community on this

issue. I reached out to leaders in the business community, and I asked

for their help. Today, I am pleased to report that United Technologies

and General Electric, as well as other corporations in Connecticut, are

sponsoring LawyerCorps Connecticut, which provides new attorneys

with the opportunity to receive a fellowship to work for a legal aid

organization for a two-year period.45 Funding for these positions

comes from the business community as opposed to state government,

and legal aid will supervise the new attorneys to make sure they are

providing excellent legal representation for their clients.46 As you can

see, this is a win-win all the way around. In the short term, those in

need will receive direct legal assistance for civil matters. In the long

term, our justice system reaps the benefits of a new generation of

attorneys whose career paths, we hope, are geared towards, at a minimum, providing pro bono service.

Finally, we have also spent a great deal of time encouraging attorneys to do more pro bono service. In 2011 and 2014, the Judicial

Branch organized summits to brainstorm ideas and energize attorneys

who want to help the disadvantaged.47 Again, we asked and they

came. The results have been excellentsome of the attorneys who

attended have been incredibly dedicated in terms of developing their

own signature pro bono programs. Just as one example, there is now a

cooperative pro bono project to provide assistance to indigent clients

in domestic violence cases.48

As one last example, I am especially proud of the Young Lawyers

Section of the Connecticut Bar Association. It stepped up to the challenge through its Pro Bono Service Campaign, which took place from

March to May 2013. The number of pro bono hours performed in con-

45 See PUBLIC SERVICE & TRUST COMMISSION PRO BONO COMMITTEE, CONN.

JUDICIAL BRANCH, ANNUAL REPORT: OCTOBER 2014, at 14 (2014), available at http://

jud.ct.gov/Committees/pst/probono/ProBonoAnnualReport2014.pdf (detailing the

inception of LawyerCorps Connecticut); LAWYERCORPS CONN., http://lawyercorpsct.org/

(last visited July 14, 2015).

46 See LAWYERCORPS CONN., http://lawyercorpsct.org/ (last visited July 14, 2015)

(listing founding corporate partners, foundations, and individual donors providing

assistance).

47 See PUBLIC SERVICE & TRUST COMMISSION PRO BONO COMMITTEE, supra note 45,

at 2, 910 (describing focus and work of 2011 and 2014 summits).

48 Id. at 13.

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\90-5\NYU501.txt

1462

unknown

Seq: 16

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW

6-NOV-15

8:46

[Vol. 90:1447

nection with the campaign was double what was anticipated, equaling

more than $2 million worth of pro bono services.49

Finally, the need for legal representation is perhaps clearest at

the appellate level. Simply put, how is a nonlawyer supposed to identify issues, write about, and ultimately argue effectively in support of

their case? In this regard, pro bono appellate lawyers are looking into

the viability of having an attorney-of-the-day program to assist selfrepresented parties in navigating the appellate process.

III

CONCLUSION

Yet with all of these efforts, there is still much more work to be

done. Self-represented litigants have changed our legal landscape and

will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. We have no choice

but to continue to explore ways to make the system accessible to them

in order to ensure that we are achieving our ultimate goal of justice

for all.

All of the changes on both the national level and in my State that

I have discussed tonight do not happen easily. At this point, however,

it is clear that we are going to have to rely heavily on technology and

extensive changes in case management to achieve our goals. The irony

is that by adopting change in our courts, we ensure that the fundamental principles that make the courts what they are in this country

will never change. In other words, by evolving to meet the needs of

today, we ensure that the rule of law and the publics trust and confidence in us to provide meaningful access to justice will remain strong.

It would be interesting to know what the speaker will be saying at

the 2035 Brennan Lecture. I cannot even envision what challenges will

exist twenty years from now, and it will be up to a new generation to

figure it out. I can tell you, however, that the Chief Justices

throughout the United States are vigilantly trying to make sure that a

fair and accessible court system will be available to the public in 2035.

In closing, I hope that I have provided you with some ideas to

bring back home, and I look forward to hearing your thoughts. Thank

you again for the tremendous privilege of addressing you this evening.

49 Press Release, Connecticut Bar Association, Young Lawyers Campaign Results in

Over $2,000,000 Worth of Pro Bono Services (July 14, 2013), available at http://articles.

courant.com/2013-07-14/community/hcrs-77436-statewide-20130712_1_connecticut-barassociation-small-firms-pro-bono-network.

Вам также может понравиться

- Fuck This CourtДокумент34 страницыFuck This CourtSarah Jeong88% (33)

- Lancesoft Offer LetterДокумент5 страницLancesoft Offer LetterYogendraОценок пока нет

- The Enterprise of Law: Justice Without the StateОт EverandThe Enterprise of Law: Justice Without the StateРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (3)

- Social Media For The CourtsДокумент27 страницSocial Media For The CourtsLawtenderОценок пока нет

- CHESS TECHNICAL GUIDELINES FOR PALARO 2023 FinalДокумент14 страницCHESS TECHNICAL GUIDELINES FOR PALARO 2023 FinalKaren Joy Dela Torre100% (1)

- US Copyright Office - Copyright Small ClaimsДокумент201 страницаUS Copyright Office - Copyright Small ClaimsTerry Hart100% (1)

- FIRsT PRELIMINARY ROUND SCRIPTДокумент7 страницFIRsT PRELIMINARY ROUND SCRIPTPuteri Rin Psikoteam MurinaОценок пока нет

- CCT LetterДокумент1 страницаCCT LetterGabeRothОценок пока нет

- Case Study - Amores Franz Nikko M FinalsДокумент5 страницCase Study - Amores Franz Nikko M FinalsJustine Martinez AmoresОценок пока нет

- Legal Perspectives On Congressional NotificationДокумент61 страницаLegal Perspectives On Congressional NotificationScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- 04 Sandefur WebsiteДокумент32 страницы04 Sandefur Websitesomya mathurОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal LawДокумент5 страницResearch Proposal Lawapi-352769442Оценок пока нет

- Ensuring An Impartial Jury in The Age of Social MediaДокумент29 страницEnsuring An Impartial Jury in The Age of Social MediaSaurav DattaОценок пока нет

- Justice and Technological InnovationДокумент13 страницJustice and Technological Innovationqwertyw123Оценок пока нет

- Thesis Major AmendmentsДокумент6 страницThesis Major AmendmentsSandra Long100% (2)

- Judicial Accountability - Meridian KohlerДокумент67 страницJudicial Accountability - Meridian KohlerSinclair LijОценок пока нет

- Business Law Legal Environment Online Commerce Business Ethics and International Issues 9th Edition Cheeseman Solutions ManualДокумент36 страницBusiness Law Legal Environment Online Commerce Business Ethics and International Issues 9th Edition Cheeseman Solutions Manualrubigoglumalooim4100% (24)

- China'S Citizen Complaint System: Prospects For AccountabilityДокумент45 страницChina'S Citizen Complaint System: Prospects For AccountabilityScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Open Internet - Statement of Commissioner Copps (10-22-09)Документ3 страницыOpen Internet - Statement of Commissioner Copps (10-22-09)Federal Communications CommissionОценок пока нет

- Angel Diaz - Testimony To NYCC Committee On TechДокумент3 страницыAngel Diaz - Testimony To NYCC Committee On TechThe Brennan Center for JusticeОценок пока нет

- Dwnload Full Business Law Legal Environment Online Commerce Business Ethics and International Issues 9th Edition Cheeseman Solutions Manual PDFДокумент36 страницDwnload Full Business Law Legal Environment Online Commerce Business Ethics and International Issues 9th Edition Cheeseman Solutions Manual PDFabatementbosomzckr5n100% (14)

- Justice Wide Open: Ian Cram - Twitt (Er) Ing Open Justice?Документ7 страницJustice Wide Open: Ian Cram - Twitt (Er) Ing Open Justice?j_townendОценок пока нет

- Re: Framework For Broadband Internet Service, GN Docket No. 10-127Документ3 страницыRe: Framework For Broadband Internet Service, GN Docket No. 10-127Phil WolffОценок пока нет

- Andrea VerasДокумент3 страницыAndrea VerasHuman Rights Project at the Urban Justice CenterОценок пока нет

- Re: Framework For Broadband Internet Service, GN Docket No. 10-127Документ3 страницыRe: Framework For Broadband Internet Service, GN Docket No. 10-127Phil WolffОценок пока нет

- Dissertation International Criminal LawДокумент8 страницDissertation International Criminal LawWebsitesThatWritePapersForYouCanada100% (1)

- Online Access To Court Records - From Documents To Data, Particulars To Patterns Peter W. Martin Cornell Law School, Peter - Martin@cornell - EduДокумент35 страницOnline Access To Court Records - From Documents To Data, Particulars To Patterns Peter W. Martin Cornell Law School, Peter - Martin@cornell - EduKirk HartleyОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law Research Paper IdeasДокумент8 страницConstitutional Law Research Paper Ideasxilllqwhf100% (1)

- Open Internet - Statement of Commissioner Baker (10-22-09)Документ2 страницыOpen Internet - Statement of Commissioner Baker (10-22-09)Federal Communications CommissionОценок пока нет

- Senator Krueger's Community Bulletin - July 2018Документ9 страницSenator Krueger's Community Bulletin - July 2018State Senator Liz KruegerОценок пока нет

- Skelos Legal Team Letter To CourtДокумент63 страницыSkelos Legal Team Letter To CourtCasey Seiler100% (1)

- 38 - 1 - 4neg Unimelb PDFДокумент47 страниц38 - 1 - 4neg Unimelb PDFIjibotaОценок пока нет

- PLJ Volume 82 Number 2 - 07 - Chief Justice Artemio v. Panganiban - Safeguarding The Liberty ..Документ16 страницPLJ Volume 82 Number 2 - 07 - Chief Justice Artemio v. Panganiban - Safeguarding The Liberty ..Rudejane TanОценок пока нет

- American Bar Association The International LawyerДокумент6 страницAmerican Bar Association The International LawyerZakir Hussain ChandioОценок пока нет

- Mechanisms of Accountability Fundamental To An Independent JudiciaryДокумент6 страницMechanisms of Accountability Fundamental To An Independent JudiciaryNew England Law ReviewОценок пока нет

- Senate Hearing, 113TH Congress - Hearing On The Report of The President's Review Group On Intelligence and Communications TechnologiesДокумент80 страницSenate Hearing, 113TH Congress - Hearing On The Report of The President's Review Group On Intelligence and Communications TechnologiesScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Public Perceptions 1Документ43 страницыPublic Perceptions 1Anonymous QVkDcVm100% (1)

- Attorney Deceit Statutes PDFДокумент69 страницAttorney Deceit Statutes PDFITALIAN333SPIRIT333Оценок пока нет

- House Hearing, 109TH Congress - Accessibility of The House Complex For Persons With Special NeedsДокумент96 страницHouse Hearing, 109TH Congress - Accessibility of The House Complex For Persons With Special NeedsScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Jurors and Social Media - Is A Fair Trial Still PossibleДокумент55 страницJurors and Social Media - Is A Fair Trial Still PossibleMIAОценок пока нет

- Written Evidence From Paul GibbonsДокумент13 страницWritten Evidence From Paul GibbonssaveFOIОценок пока нет

- The Future of Free Expression in A Digital AgeДокумент19 страницThe Future of Free Expression in A Digital AgeMaximiliano FernándezОценок пока нет

- Organized CrimeДокумент217 страницOrganized Crimerorroloco0% (1)

- Cyber Law Project (Semester-Vii)Документ24 страницыCyber Law Project (Semester-Vii)shobhit shuklaОценок пока нет

- Criminalrecords 1Документ43 страницыCriminalrecords 1Nelson Danny JuniorОценок пока нет

- House Hearing, 113TH Congress - Role of Voluntary Agreements in The U.S. Intellectual Property SystemДокумент340 страницHouse Hearing, 113TH Congress - Role of Voluntary Agreements in The U.S. Intellectual Property SystemScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Senate Hearing, 113TH Congress - Outsourcing Accountability? Examining The Role of Independent ConsultantsДокумент110 страницSenate Hearing, 113TH Congress - Outsourcing Accountability? Examining The Role of Independent ConsultantsScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Open Source Evidence and The International Criminal CourtДокумент12 страницOpen Source Evidence and The International Criminal CourtHan SamОценок пока нет

- GS 2Документ31 страницаGS 2ZerohedgeОценок пока нет

- Informant Policies & Practices Evaluation Committee ReportДокумент47 страницInformant Policies & Practices Evaluation Committee ReportLisa Bartley100% (1)

- Cdi 8 Module (Week-17)Документ3 страницыCdi 8 Module (Week-17)Wind RocksОценок пока нет

- Senate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Restoring Key Tools To Combat Fraud and Corruption After The Supreme Court's Skilling DecisionДокумент76 страницSenate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Restoring Key Tools To Combat Fraud and Corruption After The Supreme Court's Skilling DecisionScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Video-Recorded investigative interview of child victims of sexual abuse: Fundamentals and technical guidance for its implementationОт EverandVideo-Recorded investigative interview of child victims of sexual abuse: Fundamentals and technical guidance for its implementationОценок пока нет

- Duty To Access To JusticeДокумент15 страницDuty To Access To JusticeApple Abadilla100% (1)

- House Hearing, 111TH Congress - Congressional Notification: Intelligence Community Policies, Practices, and ProceduresДокумент35 страницHouse Hearing, 111TH Congress - Congressional Notification: Intelligence Community Policies, Practices, and ProceduresScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Comments To The U.S. Civil Rights Commission On Economic Impact of Criminal RecordsДокумент12 страницComments To The U.S. Civil Rights Commission On Economic Impact of Criminal RecordsThe Brennan Center for JusticeОценок пока нет

- SSRN Id4195059Документ18 страницSSRN Id4195059Maximus L MadusОценок пока нет

- Analysis of The Right of Access To Information Under Nigerian LawДокумент127 страницAnalysis of The Right of Access To Information Under Nigerian LawSeun Fasasi100% (1)

- International Criminal Law CourseworkДокумент13 страницInternational Criminal Law Courseworkf5d7ejd0100% (3)

- BB 25 PDFДокумент136 страницBB 25 PDFDee KavereОценок пока нет

- Mboychuck, CJLT Vol 15 No 2 McGill Bouclin SalyzynДокумент35 страницMboychuck, CJLT Vol 15 No 2 McGill Bouclin Salyzynjibzz741Оценок пока нет

- Public Policy and the Internet: Privacy, Taxes, and ContractОт EverandPublic Policy and the Internet: Privacy, Taxes, and ContractРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- Innovative State: How New Technologies Can Transform GovernmentОт EverandInnovative State: How New Technologies Can Transform GovernmentРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2)

- World Justice Project's Rule of Law Index 2015 ReportДокумент188 страницWorld Justice Project's Rule of Law Index 2015 ReportLatest Laws TeamОценок пока нет

- Ogi 2015Документ53 страницыOgi 2015EduardoОценок пока нет

- ReportДокумент12 страницReportLawtenderОценок пока нет

- 105 Revised and Amended: ResolutionДокумент1 страница105 Revised and Amended: ResolutionLawtenderОценок пока нет

- Interim ReportДокумент141 страницаInterim ReportLawtenderОценок пока нет

- Robots As LawyersДокумент67 страницRobots As LawyersLawtenderОценок пока нет

- Does Political Bias in The Judiciary Matter - Implications of JudДокумент33 страницыDoes Political Bias in The Judiciary Matter - Implications of JudLawtenderОценок пока нет

- MemorandumДокумент71 страницаMemorandumLawtenderОценок пока нет

- FL Supreme Court Removes Judge MurphyДокумент23 страницыFL Supreme Court Removes Judge MurphySyndicated NewsОценок пока нет

- Duty of TechnologyДокумент5 страницDuty of TechnologyLawtenderОценок пока нет

- Final OpinionДокумент45 страницFinal OpinionLawtenderОценок пока нет

- Rutherford Probation LawsuitДокумент74 страницыRutherford Probation LawsuitUSA TODAY NetworkОценок пока нет

- State V KimballДокумент10 страницState V KimballLawtenderОценок пока нет

- Judicial MisconductДокумент20 страницJudicial MisconductLawtender100% (1)

- 09 Ci 00165Документ2 страницы09 Ci 00165LawtenderОценок пока нет

- The State Bar of California Standing Committee On Professional Responsibility and Conduct FORMAL OPINION NO. 2015-193Документ7 страницThe State Bar of California Standing Committee On Professional Responsibility and Conduct FORMAL OPINION NO. 2015-193LawtenderОценок пока нет

- SSRN Id2593621Документ16 страницSSRN Id2593621LawtenderОценок пока нет

- Adb LegalstyleguideДокумент30 страницAdb LegalstyleguideLawtenderОценок пока нет

- MSF Tire and Rubber V CA (Innocent Bystander Rule-Labor LawДокумент4 страницыMSF Tire and Rubber V CA (Innocent Bystander Rule-Labor Lawrina110383Оценок пока нет

- Management of TrustsДокумент4 страницыManagement of Trustsnikhil jkcОценок пока нет

- Online Auction: 377 Brookview Drive, Riverdale, Georgia 30274Документ2 страницыOnline Auction: 377 Brookview Drive, Riverdale, Georgia 30274AnandОценок пока нет

- Econ Essay On Royal Mail Between PrivitisationДокумент2 страницыEcon Essay On Royal Mail Between PrivitisationAhila100% (1)

- Legal Ethics and Practical Exercises DigestДокумент10 страницLegal Ethics and Practical Exercises Digestalma vitorilloОценок пока нет

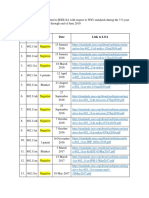

- WiFi LoAs Submitted 1-1-2016 To 6 - 30 - 2019Документ3 страницыWiFi LoAs Submitted 1-1-2016 To 6 - 30 - 2019abdОценок пока нет

- PLM860SAW: Installation and Operation ManualДокумент8 страницPLM860SAW: Installation and Operation Manualjose angel guzman lozanoОценок пока нет

- Ultra 3000 Drive (2098-In003 - En-P)Документ180 страницUltra 3000 Drive (2098-In003 - En-P)Robert BarnetteОценок пока нет

- Additional Material For TX-ZWE 2021 FinalДокумент26 страницAdditional Material For TX-ZWE 2021 Finalfarai murumbiОценок пока нет

- Cibse Lighting LevelsДокумент3 страницыCibse Lighting LevelsmdeenkОценок пока нет

- Tugas AKM II Minggu 9Документ2 страницыTugas AKM II Minggu 9Clarissa NastaniaОценок пока нет

- Kenneth A. Dockins v. Benchmark Communications, 176 F.3d 745, 4th Cir. (1999)Документ12 страницKenneth A. Dockins v. Benchmark Communications, 176 F.3d 745, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Thomas W. McArthur v. Clark Clifford, Secretary of Defense, 393 U.S. 1002 (1969)Документ2 страницыThomas W. McArthur v. Clark Clifford, Secretary of Defense, 393 U.S. 1002 (1969)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Analysis of The Novel Trafficked by Akachi Adimora Ezeigbo 1 PDFДокумент2 страницыAnalysis of The Novel Trafficked by Akachi Adimora Ezeigbo 1 PDFlord somtonwajide100% (1)

- Cdi 4 Organized Crime 2020 Covid AДокумент66 страницCdi 4 Organized Crime 2020 Covid AVj Lentejas IIIОценок пока нет

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendants-Appellants Claro M. Recto Solicitor General Pompeyo Diaz Solicitor Meliton G. SolimanДокумент9 страницPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendants-Appellants Claro M. Recto Solicitor General Pompeyo Diaz Solicitor Meliton G. Solimanvienuell ayingОценок пока нет

- Track Changes of Doctrine and Covenants Section 8Документ2 страницыTrack Changes of Doctrine and Covenants Section 8Bomo NomoОценок пока нет

- Student Profile Guide G TuДокумент5 страницStudent Profile Guide G TuumeshОценок пока нет

- Apostolic United Brethren Standards For Members/YouthДокумент60 страницApostolic United Brethren Standards For Members/YouthKatie JoyОценок пока нет

- Certificate of Compensation Payment/Tax Withheld: Commission On ElectionsДокумент9 страницCertificate of Compensation Payment/Tax Withheld: Commission On ElectionsMARLON TABACULDEОценок пока нет

- CH05 Transaction List by Date 2026Документ4 страницыCH05 Transaction List by Date 2026kjoel.ngugiОценок пока нет

- Loss or CRДокумент4 страницыLoss or CRJRMSU Finance OfficeОценок пока нет

- Topic 2Документ5 страницTopic 2Karl Anthony Tence DionisioОценок пока нет

- 2018.05.14 Letter To ATT On Their Payments To Trump Attorney Michael CohenДокумент4 страницы2018.05.14 Letter To ATT On Their Payments To Trump Attorney Michael CohenArnessa GarrettОценок пока нет

- Certificate Programme: Unit 2: Legal Requirements in Setting Up Ngos: India &south Asia 1Документ48 страницCertificate Programme: Unit 2: Legal Requirements in Setting Up Ngos: India &south Asia 1Deepak Gupta100% (1)

- Case Report Cirilo Paredes V EspinoДокумент2 страницыCase Report Cirilo Paredes V EspinoJordan ProelОценок пока нет

- SAP PST Keys ReferenceДокумент8 страницSAP PST Keys ReferenceMilliana0% (1)

- Annex 2 List of Resolutions Adopted by The SOLAS ConferencesДокумент2 страницыAnnex 2 List of Resolutions Adopted by The SOLAS ConferencesRaj GraffitiОценок пока нет