Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Management Ectopic Pregnancy SLCOG

Загружено:

Melissa Aina Mohd YusofАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Management Ectopic Pregnancy SLCOG

Загружено:

Melissa Aina Mohd YusofАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

SLCOG National Guidelines

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

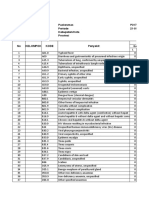

Contents

2.Management of Ectopic

Pregnancy

Page

2.1 Scope of the guideline

2.1.1 Definition

2.1.2 Importance of ectopic pregnancy

29

29

29

2.2 Aetiology

30

2.3 Epidemiology

31

2.4 Diagnosis

2.4.1 History

2.4.2 Examination

2.4.3 Investigations

32

32

33

33

2.5 Management

2.5.1 Levels of management

2.5.2 Management strategies

34

34

35

2. Special circumstances

40

2. .1 Ruptured ectopic pregnancy-management 40

2. .2 Anti-D immunoglobulin

41

2.7 Summary

41

2.8 References

43

Contributed by

Dr. A.G.S.K. Ranaraja

Dr. Saradah Hemapriya

Dr. Harsha Attapattu

Dr. R.M.A.K. Rathnayaka

28

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

Introduction

The aim of this guideline is to provide recommendations to

aid General Practitioners and Gynaecologists in the

management of Ectopic Pregnancy. This treatment could

be initiated in a primary care setting or in centres with

advanced facilities. The objective of management in

ectopic pregnancy is to make an early diagnosis, treat,

prevent complications, and consequently to improve

quality of life

2.1

fertilized egg to the uterus). On the other hand increase

availability of Gynaecologists and ultrasonography (USS)

facility, most of the ectopic pregnancies are diagnosed

earlier and appropriate management carried out with

reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. This guideline

is intended to improve the morbidity and mortality

associated with ectopic pregnancy.

2.2 Aetiology

Scope of the guideline

2.1.1 Definition

an

SLCOG National Guidelines

An ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy implanted in

abnormal location (outside of the uterus).

2.1.2 Importance of ectopic pregnancy.

Ectopic pregnancy account for maternal deaths.

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 1.8/1000(According

to the UK data). Most of the ectopic pregnancies are sub

clinical/biochemical; therefore true incidence may be

higher. The most common site of ectopic implantation is

the fallopian tube. Other sites such as the abdomen, ovary,

cervix or cornu of the uterus are far less common but are

associated with higher mortality. This higher mortality is

due to greater detection difficulty and to massive bleeding

that can result if rupture occurs at these sites. As a result of

septic abortions and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), the

incidence of ectopic pregnancies show an increased trend

over the past decades. (During the past 40 years its

incidence has been steadily increasing concomitant with

increased STD rates and associated salpingitis. Such

abnormalities of the tubes prevent normal transport of the

29

The commonest cause of ectopic pregnancy is

salphingitis (causes 50% of first time ectopic

pregnancies).

40% have no known cause. One hypothesis is that

there is slowing of transport through the fallopian

tube of the fertilized egg. This slow transport could

possibly be due to hormonal imbalance (such as

due to progesterone releasing IUD, progestin-only

oral contraceptives). This could also happen in

Artificial Reproductive Technique procedures

(ART) or possibly an abnormality of the embryo.

(e.g. chromosomal)

Cigarette smoking significantly increases a woman's

risk.

Previous history of ectopic pregnancy increases the

risk for another ectopic pregnancy. (Incidence is

7%)

About 25% of women with an ectopic pregnancy

have a history of previous surgery in the abdomen.

30

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

SLCOG National Guidelines

2.3 Epidemiology

2.4 Diagnosis

How many women suffer from an ectopic pregnancy?

The occurrence of ectopic pregnancy is reported to

be at a rate of about 1-2% of pregnancies and can occur in

any sexually active fertile woman. The increase in incidence

in the past few decades is thought to be due to two factors:

2.4.1 History

I. Increased incidence of salpingitis (infection of the

fallopian tube, usually due to a sexually transmitted

disease (STD), such as Chlamydia or Gonorrhea),

and,

II. Improved ability to detect ectopic pregnancies.

There is a marked increase in ectopic pregnancy

rate with increasing age from . per 1000 pregnancies in

women aged 15 to 24, to 21.5 per 1000 pregnancies in

women aged 35 to 44.

Most ectopic pregnancies occur in women who

have had more than one pregnancy. Only 10% to 15% of

ectopic pregnancies occur in women who have never been

pregnant before.

31

What symptoms can a woman experience with ectopic

pregnancy?

Women in whom it is suspected that they are in

danger of ectopic pregnancy, with the use of testing and

imaging it is now often possible to detect an ectopic

pregnancy

before

symptoms

develop.

It is important to be aware of the symptoms of ectopic

pregnancy because it can occur in any sexually active

woman whether or not she is using contraceptives or has

undergone tubal sterilization.

Symptoms occur as the embryo grows and as

bleeding occurs due to leaking of blood through the

fimbrial opening of the fallopian tube or from rupture of

the tube. Mild bleeding can also occur without causing

symptoms.

The most common symptoms that with which a

woman presents to a doctor are abdominal pain (90-100%

of women), delayed menses (75-90%) and unexpected

bleeding through the vagina (50-80%).

Before rupture occurs, a vague soreness or spastic

(colic) pain in the abdomen may be the only symptom

present.

Abdominal pain can be generalized, or it can be

localized on one side or both sides. About one quarter of

women also have pain in the shoulder because of

diaphragmatic irritation from blood in the abdomen.

During rupture, the pain usually becomes intense.

Other symptoms also occur though less commonly.

Dizziness and fainting occur in about one third of women

with symptoms. Pregnancy symptoms also occur in about

32

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

20% of women with symptoms. 10% of the time, there can

be an urge to have bowel movement.

2.4.2 Examination

2.4.2.1 Signs

The most common finding is tenderness in the

abdomen and pelvis. Often, a mass is felt on the side of the

uterus (adnexial mass). In about one third of women, an

enlarged uterus is found which is smaller than would be

found in a normal pregnancy, except when an interstitial

pregnancy is present. Tachycardia and hypotension can be

found if there has been profuse blood loss. However, in

most early ectopic pregnancies no abnormal findings

can be found.

SLCOG National Guidelines

2.5 Management

2.5.1 Levels of management.

Level 1.

General Practitioner (GP), Public Health Midwife (PHM),

Medical Officer of Maternal Care (MOMC)

Identification of risk mothers of ectopic pregnancy:

Past history of;

ectopic pregnancy,

septic abortion,

pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

Recommendation:

Early referral to level 2

2.4.3 Investigations

-HCG Blood levels,

Transvaginal ultrasonography.

(Grade X)

Level 2.

Base Hospital with Obstetrician and Gynaecologist.

Ultrasonography (USS) facility,

Laparotomy facility with or with out Laparoscopy facility.

Level 3.

General Hospital/Teaching Hospital with Obstetrician and

Gynaecologist with all level 2 facilities.

Human

Chorionic

Gonadotrophin

(hCG)

level

measurements available (24 hours)

33

34

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

2.5.2 Management strategies

2.5.2.1 Expectant management.

Ideal at Level 3.

(Grade Y)

Not all ectopic pregnancy ends up with maternal

morbidity and mortality1. There is 89.3 percent selfresolution of the ectopic pregnancies, but there is poor

efficacy of this method.

Expectant management is an option for;

When ectopic sac less than 2cm. with no identifiable

fetal pole and less than 50ml. of haemoperitoneum on

ultrasonography (USS).

Clinically stable woman with minimal symptoms and a

pregnancy of unknown location.

Clinically stable asymptomatic woman with an

ultrasound diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy and a

decreasing serum human chorionic gonadotrophin

levels (hCG), initially less than serum 1000 iu/l.

SLCOG National Guidelines

should be counselled about the importance of compliance

with follow-up and should be within easy access to the

hospital.

2.5.2.2 Medical Management.

However, one need to realize that selection of

patients for expectant management should be done

selectively with full compliance of the patient following

detailed counselling.

Women managed expectantly should be followed

twice weekly with serial hCG measurements and weekly by

transvaginal examinations to ensure a rapidly decreasing

hCG level (ideally less than 50% of its initial level within

seven days) and a reduction in the size of adnexial mass by

seven days.

Thereafter weekly hCG and transvaginal ultrasound

examinations are advised until serum hCG levels are less

than 20 iu/l as there are case reports of tubal rupture at

low levels of -hCG. In addition, women selected for

expectant management of pregnancy of unknown origin

(Grade Y)

Ideal at level 3

Medical therapy should be offered to suitable

women, and units should have treatment and follow-up

protocols for the use of methotrexate in the treatment of

ectopic pregnancy. In stable patients a variety of medical

treatment options are as effective as surgery.17

If medical therapy is offered, women should be

given clear information (preferably written) about the

possible need for further treatment and adverse effects

following treatment. Women should be able to return easily

for assessment at any time during follow-up.

Medical therapy option may be considered for

women with an hCG level below 3000 iu/l.20, 21

The presence of cardiac activity in an ectopic

pregnancy is associated with a reduced chance of success

following medical therapy and should be considered a

contraindication to medical therapy.11, 12

The drug of choice is methotrexate. It can be given

intravenous / intramuscular /oral or local injection at the

site of the ectopic either laparoscopically, ultra sound

guided hysteroscopically. Intramuscular methotrexate given

as a single dose calculated from patients body surface area

(50 mg/m2). For most women this will be between 75 mg.

and 90 mg. Serum hCG levels are checked on days four

and seven and a further dose is given if hCG levels have

failed to fall by more than 15% between day four and day

seven.12, 18,19

However, the success rate is 75%. According to a

small randomised controlled trial (RCT) there is no

35

36

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

difference in the outcome except in whom given by local

injection. This also gives rise to relatively low drug related

side effects. Therefore local injection of methotrexate is

preferable to its use systemically.

There are no studies to comment on the

subsequent fertility rate, as most of the trials are small.

Method of administration needs to be addressed carefully

after proper selection of patients.

For example there is high failure rate if the ectopic

is more than 2cm. of fetal pole.

2.5.2.3 Surgical management

i. Laparatomy.

Ideal at level 2

(Grade Y)

Most of the ectopic pregnancies in Sri-lanka

present after rupture and haemo-dynamically unstable.

According to randomised controlled trials (RCT) there is

controversies of stabilizing the patient and then proceeding

with the laparatomy. However, results need to be

considered cautiously. Laparotomy is preferred in haemodynamically unstable patients over laparoscopy. According

to two randomised controlled trials (RCT), laparotomy

patients give subsequent 55% intra-uterine pregnancy

(IUP) rate, 1 . % of recurrent ectopic rate and 1.8%

persistent tropoblastic activity.

SLCOG National Guidelines

randomised controlled trials (RCT) laporoscopic method

give rise to less blood loss, less hospital stay, low cost and

less post-operative analgesic requirements. This study

shows higher intra-uterine pregnancy (IUP) (70%) rate, less

recurrent ectopic (50%) and higher trophoblastic tissue

activity (12. %).

Type of surgery

i. Salphingectomy.

According to meta analysis, this method gives rise

less recurrent ectopic pregnancy rate (10%) and with no

failure of removal of all ectopic tissue. However, there is

no diferrence between laparatomy and laparoscopy except

the advandages of laparoscopy.

In the presence of a healthy contralateral tube there

is no clear evidence that salpingotomy should be used in

preference to salphingectomy.0 -12

ii. Salphingotomy.

Ideal at level 3. This depend on the consultants

preference, and is possible in level 2 as well.

A laparoscopic approach in the surgical

management of tubal pregnancy, in the haemo-dynamically

stable patient, and is preferable to a laparotomy.

This method may be preferable for the ectopic

when diagnosed early and unruptured.1 According to three

According to good quality randomised controlled

trials (RCT) there is higher rate of recurrent ectopic

associated with this method (15%) and higher rate of

trophoblastic activity (11%). However trophoblastic

activity can be managed medically. There is no significant

deference in intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) in both methods.

According to a randomised controlled trial (RCT),

that there is no additional benefit of suturing the

salphingostomy site, because the intrauterine pregnancy

(IUP) rate is similar at 12 month after the surgery with or

without suturing.

Randomised controlled trials (RCT) results suggest

that there may be a higher subsequent intrauterine

pregnancy rate associated with salphingotomy but the

magnitude of this benefit may be small. Data from future

randomised controlled trial (RCT) examining this question

37

38

ii. Laparoscopy.

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

is needed. The use of conservative surgical techniques

exposes women to a small risk of tubal bleeding in the

immediate postoperative period and the potential need for

further treatment for persistent trophoblastic tissue. Both

these risks and the possibility of further ectopic

pregnancies in the conserved tube should be discussed if

salphingotomy is being considered by the surgeon or

requested by the patient13-1

Laparoscopic salphingotomy should be considered

as the primary treatment when managing tubal pregnancy

in the presence of contralateral tubal disease and the desire

for future fertility.

In women with a damaged or absent contralateral

tube, in vitro fertilization is likely to be required if

salphingectomy is performed13-1 . Because of the

requirement for postoperative follow-up and the treatment

of persistent trophoblasts, the short-term costs of

salphingotomy are greater than salphingectomy.21 However,

if the subsequent need for assisted conception is taken into

account, an increase in intrauterine pregnancy rate of only

3% would make salphingotomy more cost effective than

salphingectomy.19 In the presence of contralateral tubal

disease the use of more conservative surgery is appropriate.

These women must be made aware of the risk of a further

ectopic pregnancy.13

39

SLCOG National Guidelines

Recommendations.

(Grade X)

1.Laparascopic method is superior to laparatomy method with

regard to less cost, shorter hospital stay, less analgesic

requirements, higher subsequent intrauterine pregnancy

(IUP) and less recurrent ectopic rates. Therefore,

laparascopic method needs to be considered as a first

option in unruptured ectopic.

2.Laparatomy is best in the case of life saving as well as with

inadequate facilities.

3.Medical management should be conducted only by wellexperienced consultants with emergency facilities at hand.

4.Expectant management should be carried out only with

reliable and compliable patients.

2.6 Special circumstances

2.6.1 Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy Management

Management of tubal pregnancy in the presence of

haemodynamic instability should be by the most

expedient method. In most cases this will be laparotomy.

There is no role for medical management in the

treatment of tubal pregnancy or suspected tubal pregnancy

when a patient shows signs of hypovolaemic shock.

Transvaginal ultrasonography can rapidly confirm the

presence of haemoperitoneum, if there is any diagnostic

uncertainty. But expedient resuscitation and surgery should be

undertaken. Experienced operators may be able to manage

laparoscopically, women with even a large haemoperitoneum

safely, but the surgical procedure which prevents further

blood loss most quickly should be used. In most centers this

will be laparotomy.

(Grade X)

40

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

2.6.2 Anti-D immunoglobulin

Non-sensitized women who are Rhesus negative

with a confirmed or suspected ectopic pregnancy should

receive anti-D immunoglobulin.

(Grade X)

SLCOG National Guidelines

ultrasonography and weekly -hCG measurements

until the level is < 10 mIU/ml.

All pregnant women who are Rh-negative should

receive Rh immunoglobulin.

2.7 Summary

Single dose methotrexate is best used for those who

are asymptomatic, whose -hCG is < 3000

mIU/ml, have tubal size < 3 cm, have no fetal

cardiac activity on ultrasonography, and will come

in to be followed closely. It cannot be used if there

is a heterotopic pregnancy.

Despite low and declining -hCG levels, tubal

rupture can still occur with methotrexate treatment.

With severe pelvic pain, monitoring of vital signs

and hematocrit can help differentiate between tubal

abortion and tubal rupture.

Most common side effects of methotrexate are;

a) stomatitis,

b) conjunctivitis,

c) mild abdominal pain of short duration. Rare

side effects include dermatitis and pruritis.

Surgery is done only if transvaginal ultrasonography

shows an ectopic pregnancy.

Laparoscopic surgery has been found to be superior

to laparotomy and can treat most patients.

Persistent ectopic pregnancy refers to the continued

growth of trophoblastic tissue after surgery. Special

attention should be given to the proximal portion

during surgery and the ectopic pregnancy should be

flushed out with suction irrigation.

Expectant management is done when ectopic

pregnancy is suspected, and transvaginal

ultrasonography does not show an ectopic

pregnancy. The patient is followed with weekly

41

42

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

2.6 References

01. Medline search 200 first quarter.

02. North American O&G journal 200 /july.

03. Progress of O&G 12th edition.

04.Green top Guideline Royal College of Obstetricians &

Gynaecologists guideline No 21 June 2004

05. Hospital medicine 200 /August

0 . Thornton K, Diamond M, DeCerney A. Linear salpingostomy for

ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1991; 18:95

109.

07. Clausen I. Conservative versus radical surgery for tubal pregnancy.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 199 ;75:812.

08. Mol BW,Hajenius PJ, Engelsbel S,Ankum WM,Hemrika DJ, van

der Veen F, et al. Is conservative surgery for tubal pregnancy

preferable to salpingectomy? An economic analysis. Br J Obstet

Gynaecol 1997; 104:8349.

09. Parker J, Bisits A. Laparoscopic surgical treatment of ectopic

pregnancy: salpingectomy or salpingostomy? Aust. N Z J Obstet

Gynaecol 1997; 37:1157. Gynecol 1999;42:318.

10. Tulandi T, Saleh A. Surgical management of ectopic pregnancy.

Clin Obstet Gynecol 1999;42:318.

11. Yao M,Tulandi T.Current status of surgical and nonsurgical

management of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril 1997; 7: 2133.

12. Sowter M, Frappell J. The role of laparoscopy in the management

of ectopic pregnancy. Rev Gynaecol Practice 2002;2:7382.

13. Silva P, Schaper A, Rooney B. Reproductive outcome after 143

laparoscopic procedures for ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril 1993;

81:7105.

14. Job-Spira N, Bouyer J, Pouly J, Germain E, Coste J,AubletCuvelier B, et al. Fertility after ectopic pregnancy: first results of a

population-based cohort study in France.Hum Reprod 199 ;11:99

104.

15. Mol B,Matthijsse H,Tinga D,Huynh T,Hajenius P,Ankum W, et al.

Fertility after conservative and radical surgery for tubal

pregnancy.Hum Reprod 1998;13:18049.

1 . Bangsgaard N,Lund C,Ottesen B,Nilas L.Improved fertility

following conservative surgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Br

J Obstet Gynaecol 2003; 110:7 570.

17. Lipscomb G, Bran D, McCord M, Portera J, Ling F.Analysis of

three hundred fifteen ectopic pregnancies treated with single-dose

methotrexate. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 178:13548.

43

SLCOG National Guidelines

18. Saraj A,Wilcox J, Najmabadi S, Stein S, Johnson M, Paulson R.

Resolution of hormonal markers of ectopic gestation: a

randomized

trial

comparing

single-dose

Intramuscular

methotrexate with salpingostomy. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:98994.

19. Sowter M, Farquhar C, Petrie K, Gudex G. A randomized trial

comparing single dose systemic methotrexate and laparoscopic

surgery for the treatment of unruptured tubal pregnancy. Br J

Obstet Gynaecol 2001; 108:192203.

20. Sowter M, Farquhar C, Gudex G.An economic evaluation of single

dose systemic methotrexate and laparoscopic surgery for the

treatment of unruptured ectopic pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

2001; 108:20412.

21. Mol B,Hajenius P,Engelsbel S,Ankum W,Hemrika D,Van der Veen

F, et al. Treatment of tubal pregnancy in the Netherlands:an

economic comparison of systemic methotrexate administration

and laparoscopic salpingostomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;

181:94551.

44

Вам также может понравиться

- Brief DescriptionДокумент7 страницBrief DescriptionPrincess Pilove GawongnaОценок пока нет

- Ectopic PregnancyДокумент5 страницEctopic PregnancyFaith FuentevillaОценок пока нет

- No. 34. Management of Infertility Caused by Ovulatory DysfunctionДокумент19 страницNo. 34. Management of Infertility Caused by Ovulatory DysfunctionAnnisa JuwitaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal KEДокумент16 страницJurnal KEMuhammad Harris ZainalОценок пока нет

- Ectopic Pregnancy-American Family PhysicianДокумент8 страницEctopic Pregnancy-American Family PhysicianSi vis pacem...Оценок пока нет

- Ultrasonographic Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic PregnancyДокумент25 страницUltrasonographic Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic PregnancyMuhammad AbeeshОценок пока нет

- Ectopic Pregnancy Diagnosis and TreatmentДокумент39 страницEctopic Pregnancy Diagnosis and TreatmentFecky Fihayatul IchsanОценок пока нет

- Pregnant Woman TemplateДокумент11 страницPregnant Woman TemplateRegine Mae Morales EncinadaОценок пока нет

- Tubal Ectopic PregnancyДокумент38 страницTubal Ectopic Pregnancy6ixSideCreate MОценок пока нет

- Nama: Zaimah Shalsabilla Kelas: Alpha NIM: 04011181520071Документ11 страницNama: Zaimah Shalsabilla Kelas: Alpha NIM: 04011181520071shalsaОценок пока нет

- Early Pregnancy Loss - Practice Essentials, Background, PathophysiologyДокумент10 страницEarly Pregnancy Loss - Practice Essentials, Background, PathophysiologyAldair SanchezОценок пока нет

- Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy PB193Документ13 страницTubal Ectopic Pregnancy PB193Sheyla Orellana PurillaОценок пока нет

- Bleeding During PregnancyДокумент69 страницBleeding During PregnancyMohnnad Hmood AlgaraybhОценок пока нет

- Ectopic PregnancyДокумент24 страницыEctopic PregnancybertouwОценок пока нет

- Practice Bulletin: Medical Management of Ectopic PregnancyДокумент7 страницPractice Bulletin: Medical Management of Ectopic PregnancyChangОценок пока нет

- Ectopic Pregnancy: MoreДокумент18 страницEctopic Pregnancy: Moreaaaaa_01Оценок пока нет

- Ectopic Pregnancy22Документ43 страницыEctopic Pregnancy22Sunil YadavОценок пока нет

- Ectopic Pregnancy: Causes, Symptoms & TreatmentДокумент10 страницEctopic Pregnancy: Causes, Symptoms & TreatmentXo Yem0% (1)

- Ectopic Pregnancy ThesisДокумент8 страницEctopic Pregnancy ThesisWriteMyPaperCollegeSingapore100% (2)

- Practice Bulletin: Management of Preterm LaborДокумент10 страницPractice Bulletin: Management of Preterm LaborXimena OrtegaОценок пока нет

- Incomplete AbortionДокумент4 страницыIncomplete AbortionAira Jane MuñozОценок пока нет

- Early Pregnancy Problems: Presented byДокумент28 страницEarly Pregnancy Problems: Presented byMalk OmryОценок пока нет

- NCM 109-Module 1 Lesson 1Документ30 страницNCM 109-Module 1 Lesson 1MARY ROSE DOLOGUINОценок пока нет

- Assessment and Management of Miscarriage: Continuing Medical EducationДокумент5 страницAssessment and Management of Miscarriage: Continuing Medical EducationCallithya BentleaОценок пока нет

- Ectopic PregnancyДокумент17 страницEctopic PregnancyMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Threatened Abortion ReportДокумент8 страницThreatened Abortion ReportMohamad RaisОценок пока нет

- Ectopic Pregnancy: by Amielia Mazwa Rafidah Obstetric and Gynecology DepartmentДокумент43 страницыEctopic Pregnancy: by Amielia Mazwa Rafidah Obstetric and Gynecology DepartmentAlrick AsentistaОценок пока нет

- Best modality for diagnosing ectopic pregnancyДокумент31 страницаBest modality for diagnosing ectopic pregnancyantonio91uОценок пока нет

- Infertility PDFДокумент12 страницInfertility PDFdian_c87100% (1)

- Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy: (Replaces Practice Bulletin Number 191, February 2018)Документ18 страницTubal Ectopic Pregnancy: (Replaces Practice Bulletin Number 191, February 2018)Rubio Sanchez JuanОценок пока нет

- Early Pregnancy LossДокумент20 страницEarly Pregnancy LossRima HajjarОценок пока нет

- Articles of Abnormal Obstetrics CasesДокумент11 страницArticles of Abnormal Obstetrics CasesMarjun MejiaОценок пока нет

- Ectopic PregnancyДокумент3 страницыEctopic PregnancySiska FriedmanОценок пока нет

- Ectopic Pregnancy: Medlineplus TopicsДокумент9 страницEctopic Pregnancy: Medlineplus TopicsJonathan BendecioОценок пока нет

- INTRODUCTIO1Документ10 страницINTRODUCTIO1Diane ChuОценок пока нет

- Detecting and Managing Ectopic PregnancyДокумент21 страницаDetecting and Managing Ectopic Pregnancyﻣﻠﻚ عيسىОценок пока нет

- Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management of Ectopic PregnancyДокумент18 страницClinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management of Ectopic PregnancyJorge MincholaОценок пока нет

- Medical and Surgical Complications of Pregnancy 08 AДокумент139 страницMedical and Surgical Complications of Pregnancy 08 A2012Оценок пока нет

- Ectopic PregnancyДокумент18 страницEctopic PregnancyWondimu EliasОценок пока нет

- Ectopic PregnancyДокумент26 страницEctopic PregnancyMalek.Fakher1900Оценок пока нет

- Abortion and Ectopic PregnancyДокумент3 страницыAbortion and Ectopic PregnancyJefelson Eu Palaña NahidОценок пока нет

- PRESENTING PATIENTДокумент70 страницPRESENTING PATIENTCharmaineTadereraОценок пока нет

- Breast CancerДокумент6 страницBreast CancercchiechieОценок пока нет

- Elizabeth G. Querubin BSN 3E1-9 - Group 195 A Ectopic PregnancyДокумент16 страницElizabeth G. Querubin BSN 3E1-9 - Group 195 A Ectopic PregnancyLizeth Querubin97% (38)

- Ectopic Pregnancy1Документ34 страницыEctopic Pregnancy1Kreshimaricon FurigayОценок пока нет

- 2022.TP (Ectopic Pregnancy) NOUNSДокумент6 страниц2022.TP (Ectopic Pregnancy) NOUNSWilson BenitezОценок пока нет

- PREGNANC1Документ20 страницPREGNANC1SriramОценок пока нет

- Belle Preterm BirthДокумент9 страницBelle Preterm BirthRashed ShatnawiОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis of Preterm Labor and Overview of Preterm BirthДокумент15 страницDiagnosis of Preterm Labor and Overview of Preterm BirthKenny IncsОценок пока нет

- Prolonged PregnancyДокумент41 страницаProlonged PregnancyArif Febrianto100% (1)

- Embarazo Ectopico Tubarico ACOG 2018Документ13 страницEmbarazo Ectopico Tubarico ACOG 2018Jesus SuarezОценок пока нет

- Postterm Pregnancy and IUFDДокумент24 страницыPostterm Pregnancy and IUFDNejib M/AminОценок пока нет

- CS - PP FinalДокумент30 страницCS - PP FinalNicole ArandingОценок пока нет

- Case Study On Ectopic PregnancyДокумент4 страницыCase Study On Ectopic PregnancyDalene Erika GarbinОценок пока нет

- Ectopic Pregnancy TestДокумент20 страницEctopic Pregnancy Testali alrashediОценок пока нет

- EctopicДокумент13 страницEctopicAnonymous P5efHbeОценок пока нет

- Guide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical PracticeОт EverandGuide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical PracticeОценок пока нет

- Creamy Chicken EnchiladasДокумент2 страницыCreamy Chicken EnchiladasMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Enchiladas With Smoked Salmon English 1Документ2 страницыEnchiladas With Smoked Salmon English 1Melissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Capone A Final ProposalДокумент8 страницCapone A Final ProposalMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Recipe - Spiced Pecan ChickenДокумент1 страницаRecipe - Spiced Pecan ChickenMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Chicken Enchiladas With Chopped CabbageДокумент1 страницаChicken Enchiladas With Chopped CabbageMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Chicken MitochondriaДокумент9 страницChicken MitochondriaMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Mel's Case Write Up 2Документ18 страницMel's Case Write Up 2Melissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- TV Recipe - Chicken Enchiladas - April 2011Документ1 страницаTV Recipe - Chicken Enchiladas - April 2011Melissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- David Stroka Recipes - Whole EnchiladaДокумент1 страницаDavid Stroka Recipes - Whole EnchiladaMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Medieval Norwegian Baked Cinnamon-Saffron ChickenДокумент2 страницыMedieval Norwegian Baked Cinnamon-Saffron ChickenMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Chicken Chicken Chicken: Chicken Chicken: Doug Zongker University of WashingtonДокумент3 страницыChicken Chicken Chicken: Chicken Chicken: Doug Zongker University of WashingtonMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Speciesnotes DomesticfowlДокумент4 страницыSpeciesnotes DomesticfowlMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- KCBS Meat Inspections GuideДокумент2 страницыKCBS Meat Inspections GuideMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Anglo-Saxon Chicken Stew with Herbs & BarleyДокумент1 страницаAnglo-Saxon Chicken Stew with Herbs & BarleyMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Boston Medical Center Nutrition Resource Center: Recipe by Tracey BurgДокумент1 страницаBoston Medical Center Nutrition Resource Center: Recipe by Tracey BurgMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Pan Seared Orange ChickenДокумент2 страницыPan Seared Orange ChickenMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Easy Roasted Chicken Recipe for OneДокумент1 страницаEasy Roasted Chicken Recipe for OneMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- 3759 Frozen To Finish RecipesДокумент4 страницы3759 Frozen To Finish RecipesMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- ChickenpoxДокумент2 страницыChickenpoxMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- ChickenДокумент2 страницыChickenMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Chicken Chicken Chicken: Chicken Chicken: Doug Zongker University of WashingtonДокумент3 страницыChicken Chicken Chicken: Chicken Chicken: Doug Zongker University of WashingtonMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Chicken Prices (: Boneless/Skinless Chicken Breast................ $2.29/lbДокумент1 страницаChicken Prices (: Boneless/Skinless Chicken Breast................ $2.29/lbMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Chicken Goujons - DipДокумент1 страницаChicken Goujons - DipMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Chicken Primavera Grocery ListДокумент1 страницаChicken Primavera Grocery ListMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Production of Transgenic Chickens Using Lentiviral VectorsДокумент3 страницыProduction of Transgenic Chickens Using Lentiviral VectorsMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Chicken GoujonsДокумент1 страницаChicken GoujonsMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Vals ChickenДокумент1 страницаVals ChickenMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Easy Roasted Chicken Recipe for OneДокумент1 страницаEasy Roasted Chicken Recipe for OneMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- LH Poultry Home Production Broiler ChickensДокумент4 страницыLH Poultry Home Production Broiler ChickensMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Chicken Forage ListДокумент2 страницыChicken Forage ListMelissa Aina Mohd YusofОценок пока нет

- Hubungan Pengetahuan Dan Sikap Tentang Antenatal Care Dengan Kunjungan K4 Di Puskesmas Seririt IДокумент12 страницHubungan Pengetahuan Dan Sikap Tentang Antenatal Care Dengan Kunjungan K4 Di Puskesmas Seririt IKETUT TRISIKA PIBRYANAОценок пока нет

- Course Syllabus-Maternity TheoryДокумент6 страницCourse Syllabus-Maternity TheoryannairishybОценок пока нет

- FGDHGNДокумент26 страницFGDHGNAchmad YunusОценок пока нет

- PSmarkup - ARTIKEL PRENATAL MASSAGE-LILIS SURYA WATIДокумент9 страницPSmarkup - ARTIKEL PRENATAL MASSAGE-LILIS SURYA WATIRiya WahyuniОценок пока нет

- Forceps Delivery and Vaccum ExtractionДокумент84 страницыForceps Delivery and Vaccum ExtractionushaОценок пока нет

- 2nd Trimester BleedingДокумент50 страниц2nd Trimester BleedingRaiden VizcondeОценок пока нет

- Course Syllabus Course Name: Obstetrics and Gynecology-2 Sixth YearДокумент18 страницCourse Syllabus Course Name: Obstetrics and Gynecology-2 Sixth Yearali tahseenОценок пока нет

- Obesteric Gynacology Short Notes For Usmle Step 2Документ32 страницыObesteric Gynacology Short Notes For Usmle Step 2Rodaba Ahmadi Meherzad100% (1)

- OB ObjectivesДокумент2 страницыOB ObjectivesDavid LadinОценок пока нет

- Is Sex During Pregnancy Safe?Документ3 страницыIs Sex During Pregnancy Safe?mirrawahabОценок пока нет

- FPДокумент4 страницыFPHearty ArriolaОценок пока нет

- Antenatal Care Counseling: Roll No 11 To 23Документ11 страницAntenatal Care Counseling: Roll No 11 To 23adityarathod612Оценок пока нет

- 2011 - Unsafe Abortion and Postabortion Care - An OverviewДокумент9 страниц2011 - Unsafe Abortion and Postabortion Care - An OverviewJeremiah WestОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis of PregnancyДокумент4 страницыDiagnosis of PregnancyIsrael WoseneОценок пока нет

- Lapkas Ruptur UteriДокумент10 страницLapkas Ruptur UterirandyardinalОценок пока нет

- Puerperal Sepsis Diagnosis and TreatmentДокумент36 страницPuerperal Sepsis Diagnosis and TreatmentRufai Abdul WahabОценок пока нет

- Sample First Trimester Twin Ultrasound ReportДокумент2 страницыSample First Trimester Twin Ultrasound ReportPriyankaОценок пока нет

- A Century of Labor Induction MethodsДокумент4 страницыA Century of Labor Induction MethodsSimon ReichОценок пока нет

- Laporan Bulanan Lb1: 0-7 HR Baru LДокумент20 страницLaporan Bulanan Lb1: 0-7 HR Baru LOla SarlinaОценок пока нет

- No. 31. Assessment of Risk Factors For Preterm BirthДокумент9 страницNo. 31. Assessment of Risk Factors For Preterm BirthenriqueОценок пока нет

- Breech PresentationДокумент46 страницBreech PresentationushaОценок пока нет

- Post Partum HemorrhageДокумент18 страницPost Partum Hemorrhageeric100% (1)

- Multiple PregnancyДокумент7 страницMultiple Pregnancymohammed alkananiОценок пока нет

- Trias RevisiДокумент20 страницTrias RevisiDion PratamaОценок пока нет

- Cesarean Section Audit FormatДокумент6 страницCesarean Section Audit FormatRahul JalauniaОценок пока нет

- Ojsadmin, 993Документ6 страницOjsadmin, 993pondyОценок пока нет

- Duran, Fatima Medriza B. - DR Written OutputsДокумент9 страницDuran, Fatima Medriza B. - DR Written OutputsFatima Medriza DuranОценок пока нет

- Obstetrics V10 Common Obstetric Conditions Chapter Pathology of The Placenta 1663285373Документ11 страницObstetrics V10 Common Obstetric Conditions Chapter Pathology of The Placenta 1663285373Nurliana NingsihОценок пока нет

- Mark Fredderick R. Abejo RN, MAN: Maternal and Child Nursing BulletsДокумент10 страницMark Fredderick R. Abejo RN, MAN: Maternal and Child Nursing BulletsMark DaenosОценок пока нет

- Acog Practice Bulletin Summary: Gestational Hypertension and PreeclampsiaДокумент4 страницыAcog Practice Bulletin Summary: Gestational Hypertension and PreeclampsiaAji PatriajatiОценок пока нет