Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Firm Networks and Firm Development-2

Загружено:

Carola KamelАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Firm Networks and Firm Development-2

Загружено:

Carola KamelАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514 540

Firm networks and firm development: The role of

the relational mixB

Christian Lechnera,*, Michael Dowlingb,1, Isabell Welpec,2

a

ESC Toulouse, 20, Bd. Lacrosses, 31068 Toulouse Cedex 7, France

University of Regensburg, Management of Innovation and Technology, Regensburg 93040, Germany

c

Exist-HighTEPP Program, University of Regensburg, Regensburg 93040, Germany

Abstract

This study examines the role of different networks, called the relational mix, on the development

of the entrepreneurial firm. Our regression analysis of survey data from 60 venture capital-financed

firms questions the importance of network size on firm development. Rather, our results suggest that

different types of networks are more important for firm development. In particular, we found a

significant positive relationship for reputational networks and a weak significant negative

relationship for cooperative technology networks at founding with time-to-break-even. Social

networks at founding have no direct effect on time-to-break-even and a significant negative

relationship with sales in the years after foundation. Furthermore, our findings show the important

role of marketing information and co-opetition networks (relationships with direct competitors) on

firm development in the years after foundation. These results suggest that the relational mix is a more

appropriate construct for explaining network development than network size alone.

D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship; Networks; Firm growth; Performance

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2003 Babson Kauffman Entrepreneurship Research

Conference, June 57, at Babson College, Boston, MA.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +33 561 29 49 23; fax: +33 561 29 49 94.

E-mail addresses: c.lechner@esc-toulouse.fr (C. Lechner)8 Michael.Dowling@wiwi.uni-regensburg.de

(M. Dowling)8 Isabell.Welpe@Exist-Hightepp.de (I. Welpe).

1

Tel.: +49 941 9433226; fax: +49 941 943 3230.

2

Tel.: +49 941 943 1704; fax: +49 941 943 3230.

0883-9026/$ - see front matter D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.02.004

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

515

1. Executive summary

The use of external relationships is considered an important development factor for the

entrepreneurial firm. Previous research on inter-firm networks has focused on the role of

the entrepreneur in network building, on the initial size of an entrepreneurial firms

network in regard to firm performance, or on structural characteristics of networks. This

study addressed a different question: During the process of firm development, what is the

value of different kinds of network relationships?

We adapted a model of the brelational mixQ (i.e., that firms use different types of

networks in different development phases). The relational mix consists of value-added

networks that go beyond exclusively economic relationships and includes:

social networks: relationships with other firms based on strong personal relationships

with individuals such as friends, relatives, long-standing colleagues that became friends

before foundation, and so forth;

reputational networks: made up of partner firms that are market leaders, or highly

regarded firms or individuals, and where one of the main objectives in entering into this

relationship is to increase the entrepreneurial firms credibility;

marketing information networks: relationships that allow for the flow of market

information through distinct relationships with other individuals / firms;

co-opetition networks: relationships with direct competitors;

co-operative technology networks: technology alliances involving joint technology

development or innovation projects.

The adapted model assumes that the relational mix changes with a firms development

and that inability to change leads to a growth barrier.

To test hypotheses based on this model, we used survey data from 60 venture capitalfinanced start-up firms of less than 10 years of age in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland.

The evidence from the regression analysis supports our model: the relational mix is a more

important factor for explaining firm development than sheer network size. Reputation

networks have a positive influence while cooperative technology networks at foundation

have a negative effect on time to break-even. Entrepreneurs should be aware of the

important signaling effects that reputational partners can have in overcoming liability of

newness. Early technology partnering might be an indicator that firms are not yet ready to

exploit business opportunities or not attractive enough to enter into more value-adding

partnerships. Moreover, it seems that firms use their initial technology base to exploit a

business opportunity and that technology partnering is a means to enhance the technology

platform later on to prepare the company for the future. We also found that marketing

information networks and co-opetition networks in the years after foundation are

positively associated with sales. Relationships with competitors play an important role

for firm development since competitors can be a source for firm development when used

as sub-contractors, or for the joint realization of larger projects that might otherwise be

unattainable for the start-up. In this sense, co-opetition networks seem to increase the

entrepreneurial firms flexibility and to ensure sales growth in times of uncertainty. We did

not find a significant positive influence of social networks at foundation on time-to-break-

516

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

even. It seems that while constituting the start-up base of the entrepreneurial firm and

being the most common type of relationship at the beginning of the firm, social networks

are not a good discriminator for the success or speed of firm development. Social networks

seem to have an indirect effect. Over-reliance on social networks over time may in fact

constitute a growth problem, since it may indicate that firms are not capable of developing

other important ties. In conclusion, our study suggests that networking should be a

proactive task of entrepreneurs and that strategic network building over time is an

important factor for the development of the entrepreneurial firm. Further research on the

development of certain network types, the role of management style on developing

networks, and the contingent value of network types is needed to enhance our

understanding of the development processes of entrepreneurial firms.

2. Introduction and literature

Survival, performance, and development of the entrepreneurial firm are at the heart of

entrepreneurship research (Gartner, 1985; Bygrave and Hofer, 1991; Venkataraman, 1997;

Virtanen, 1997; Shane and Venkataraman, 2000). Entrepreneurial firms are characterized

by a lack of internal resources and other start-up handicaps as expressed in the theoretical

constructs of liability of newness (Stinchcombe, 1965) and liability of smallness (Baum,

1996). The strategic use of external resources through inter-firm networks in many

different industries (Powell, 1987; Lorenzoni and Ornati, 1988; Jarillo, 1989) that are often

embedded in regional clusters (Boari and Lipparini, 2000; Lechner and Dowling, 2000) is

regarded as one effective means to overcome these liabilities. In this context, inter-firm

networks are considered an important model of organization development (Richardson,

1972; Powell, 1987, 1990) to enable an entrepreneurial firm to grow and survive (Jarillo,

1988; Lorenzoni and Ornati, 1988; Nohria, 1992; Johannisson, 1998; Venkataraman and

Van de Ven, 1998; Freel, 2000).

There is a long history of research on networks in the management and organization

theory literature. Networks can be defined as a specific set of linkages between a defined

set of actors with the characteristic that the linkages as a whole may be used to interpret the

social behavior of the actors involved (Mitchell, 1969; Alba, 1982; Lincoln, 1982).

Different types of relations define different types of networks even if the same units are

connected (Knoke and Kuklinsky, 1983).

Network research distinguishes three components: network content, network structure,

and network governance in order to explain the role of networks in firm performance.

According to the theory of structural embeddedness, network structure and a firms or a

persons network position are considered to be both opportunities and constraints (Aldrich

and Zimmer, 1986). Favorable positions are regarded as network resources (Granovetter,

1974, 1985; Burt, 1992; Easton, 1992; Hakansson and Snehota, 1995; Gulati, 1999;

McEvily and Zaheer, 1999); over-embeddedness, however, (btrapped-in-its-own-netQ) can

lead to inability to act (Uzzi, 1997; Gargiulo and Benassi, 2000). A rich literature suggests

that networks are a particular governance form in which the development of trust plays a

major role in influencing resource exchange and costs compared to market coordination or

integration of activities (Richardson, 1972; Thorelli, 1986; Powell, 1987, 1990; Larson,

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

517

1992; Lorenzoni and Lipparini, 1999). In this sense, inter-firm networks constitute a third

way of organizing the business, which is neither by markets nor by hierarchies (Di

Maggio, 1986; Powell, 1990; Lorenzoni, 1992; Jarillo, 1993).

Empirical research has shown an association between the development and

transformation of relationships, size, and growth of a firms inter-firm networks and firm

growth (Jarillo, 1989; Zhao and Aram, 1995; Ardichvili and Cardozo, 2000; Chell and

Baines, 2000; Huggins, 2000; Delmar et al., 2003; Hoang and Antoncic, 2003; Sawyer et

al., 2003). Besides research on personal networking and networks, network content

research has concentrated strongly on the differences between strong and weak ties (Hoang

and Antoncic, 2003), otherwise known as the structural approach (McEvily and Zaheer,

1999). Recently, it was shown that specific kinds of relations (network content) are more

important in a different economic context (Gulati and Higgins, 2003).

Research on firm networks as a mode of transaction governance, the role of strong and

weak ties, and the analysis of structural properties of networks has produced important

insights (Hoang and Antoncic, 2003). However, research on different network types and

on network evolution remains relatively underdeveloped. bThe aggregate network can be

viewed as an overlapping set of networks of different transactional content. The only

conceptually meaningful strategy of analysis is to distinguish each network by its content,

[and] analyze it separatelyQ (Fombrun, 1982, p. 280). And as Burt (1997, p. 357) observed,

bnetwork content is rarely a variable in the studiesanalysts agree that informal

coordination through interpersonal networks is important as a form of social capital, but

their eyes go shifty like a cornered ferret if you push past the network metaphor for details

about how specific kind of relations matter.Q

Networking has also been found to be important for entrepreneurial firms. Most

research in this setting has analyzed egocentric networks (i.e., the relationships of one

focal actor with other actors) (Wassermann and Faust, 1994; Johannisson, 1998). Because

of the new ventures liabilities, such firms must mobilize social relationships (Starr and

MacMillan, 1990) to access external resources. An entrepreneurs personal networks are

all relationships between an entrepreneur and other individuals (Dubini and Aldrich,

1991). An entrepreneurs social networks are strong personal ties such as family and

friends. Research has shown that the entrepreneurs personal and social networks maybe

are the most important strategic resources of entrepreneurs for the start-up firm (Dubini

and Aldrich, 1991; Ostgaard and Birley, 1994; Johannisson, 1995, 1998, 2000; Lipparini

and Sobrero, 1997; Aldrich, 1999; Ardichvili et al., 2003). Organizational networks or

inter-firm networks are relations between organizations that can have various functions,

also called sub-networks according to their relational content (Dubini and Aldrich, 1991;

Lomi, 1997; Podolny and Page, 1998; Lechner and Dowling, 2000). The merging of

personal and organizational networks seems to be a common feature of young firms (Zhao

and Aram, 1995; Johannisson, 1998, 2000). Founders and the firm are inseparable at startup (Dollinger, 1985; Begley and Boyd, 1986). As the firm grows, the founders personal

networks and firm networks merge (Zhao and Aram, 1995; Hite and Hesterly, 2001;

Cooper, 2002). These merged networks can be considered an organizational form

(Johannisson, 2000).

Initially, it seems that networking for entrepreneurial firms is based on pre-existing

relationships, which become more complex over time by having different functions and

518

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

being more socially embedded: social relations are transformed into socio-economic and,

finally, into more complex relations (Larson and Starr, 1993). Green and Brown (1997)

have suggested that over time, newly developed organizational relationships become more

important than the a priori personal networks. Previous research has shown that the overall

network structure of egocentric networks changes from an unplanned to a planned and,

finally, a structured network (Lorenzoni and Ornati, 1988; Lorenzoni and Baden-Fuller,

1995). Once structured, however, it seems that both over-embeddedness (Uzzi, 1997;

Gargiulo and Benassi, 2000) and a firms limited relational capability (i.e., the capability to

establish, maintain, and develop relationships) (Dyer and Singh, 1998; Lorenzoni and

Lipparini, 1999; Pihkala et al., 1999; Lechner and Dowling, 2003) poses a potential barrier

to growth. However, this research does not explain which network types (content) are most

important to manage or how firms should overcome these growth barriers.

Research on network types and performance has focused on pre-start-up activities in

order to explain nascent entrepreneurship (i.e., personal networks have been analyzed at or

prior to the creation of the company in terms of size and networking activity) (Aldrich,

1999). Context-specific research investigated the positive or negative role of social

networks at start-up, but which types (content) of network matter most for firm

performance have not been studied extensively (Ostgaard and Birley, 1994). Some

research was conducted on the role of single network types such as reputational (e.g.,

Stuart et al., 1999) and cooperative technology networks (e.g., Deeds and Hill, 1996;

Kelley and Rice, 2002), but little is known for example about the role of co-opetition

networks. Studies analyzing multiple network types are rare (Baum et al., 2000).

Moreover, entrepreneurship research on networks usually lacks a development perspective

(Hoang and Antoncic, 2003) and an analysis of the value of different ties (Gulati and

Westphal, 1999). It has been argued that research bon the process of network development

in the entrepreneurial contextQ and the link between process and firm performance is the

most promising path (Hoang and Antoncic, 2003, p. 12).

Lechner and Dowling (2003) proposed a network development model based on varying

network types. Based on case study research in a German IT cluster, they identified that

firms use relationships for a variety of purposes and that every firm has an individual

relational mix. They argued that the relational mix (i.e., the different types of networks)

changes over time in order to enable firm growth. Finally, they proposed a four-phase

development model of entrepreneurial firms. In phase 1, firms seek to overcome liability

of newness by basing the development of the network mainly on social (understood as

strong ties such as family and friends) and reputational networks (relationships with

prominent firms that can lend the young firm reputation). While the relative importance of

social and reputational networks decreases with the firms development, co-opetition

networks (i.e., cooperation with competitors) increase over time. In phase 2, firms use

marketing information and co-opetition networks to overcome the usual period of unstable

sales growth; in phase 3, co-opetition remains a relevant issue but cooperative technology

networks are most important. Finally, in phase 4, firm growth is limited by path-dependent

relational capability that eventually reaches its limits and leads to the reconfiguration of a

more stable network by introducing hierarchic levels within the network or to the

integration of activities previously performed outside the firm. This qualitative study

seems to be one of the few where different network types were used to understand the role

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

519

of networks at and beyond foundation, but the importance of different network types at

and beyond foundation and their impact on the performance of the entrepreneurial firm

have not been tested empirically with larger samples.

For the study reported here, we adapted the model of the relational mix developed by

Lechner and Dowling (2003). We tested the influence of their proposed network types at

and beyond foundation by using their main arguments concerning the importance of

particular networks. Our first and fundamental research question is: Is the relational mix a

better predictor of firm performance, both at and after foundation, than the size of the

overall network?

3. Development of hypotheses

3.1. Relational mix versus network size

Different studies have proposed a simple relationship between network size and firm

performance (Johannisson, 2000). Case study research has suggested that network size is

related to the growth of firms (Zhao and Aram, 1995). Inter-firm networks can provide

access to complementary resources to develop, produce, and market products (Deeds and

Hill, 1996). Entering into inter-firm relationships has costs, risks, and benefits. Costs

include both financial resources and time. The marginal benefits of alliances can decline

while costs increase (Deeds and Hill, 1996). Some researchers that have specifically

studied technology partnering have demonstrated a curvelinear relationship between

network size and performance (Deeds and Hill, 1996). It has been argued that the

relational capability (i.e., the capability to enter and maintain relationships) is limited

(Pihkala et al., 1999) but path-dependent. In other words, firms learn to better manage

more relationships over time (Deeds and Hill, 1996; Lechner and Dowling, 2003). In

addition, certain types of inter-firm relationships can be managed in greater number

(Rothaermel and Deeds, 2001). It seems, however, that for young firms, there is still a

positive relationship between size and performance (Rothaermel, 2001). A start-ups initial

performance has been shown to increase with the size of the alliance network of firms at

foundation (Baum et al., 2000). Overall, previous research has led to the general

hypothesis that network size is a good indicator for explaining the performance of young

firms.

Hypothesis 1. Network size (i.e., the total number of network ties) increases firm

performance.

However, it has also been argued that the size of the network hides more important

network properties (Fombrun, 1982). These properties include the relational mix (i.e.,

different network types; social networks, co-opetition networks, marketing information

networks, reputation networks, and cooperative technology networks) that enabled growth

in different stages of firm development (Lechner and Dowling, 2003). These types of

networks are not pure exchange networks but are socially embedded complex relationships

(Larson, 1992). A more fine-grained picture of network development should therefore be a

better indicator for firm development than sheer network size (measured as total numbers

520

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

of relations). In Section 3.2, we develop a set of more detailed hypotheses linking specific

types of networks and therefore the relational mix to start-up and later performance in

entrepreneurial firms.

3.2. Social networks

We define social networks as strong and active relationships with other individuals that

existed before the creation of the firm. These include family (non-business), friends, and

former colleagues. It seems to us important to distinguish between active relationships

(i.e., those effectively used for business purposes) and existing but unused relationships,

called latent networks (Ramachandran and Ramnarayan, 1993), in order to understand the

actual role of networks for firm performance.3 Family and friends (i.e., non-business

networks) are considered to be part of the start-up resources of the firm (Johannisson,

2000). The entrepreneurs social networks are regarded as an important resource for the

start-up firm (Ostgaard and Birley, 1994; Johannisson, 1995; Lipparini and Sobrero,

1997). These strong ties have various benefits for the entrepreneur at the start of the firm

by providing access to resources. Social networks help entrepreneurs avoid opportunism

and uncertainty through trust, predictability, and voice. Because the entrepreneur can trust

the other party, it is easier to predict his/her behavior, avoid problem in the relationship,

but better deal with them when they do occur (Aldrich, 1999). Therefore, resource access

is immediate and the working relationship does not need a bwarm-up periodQ in which the

two partners get to know each other. As a consequence, such networks should allow

entrepreneurs to achieve performance targets faster, such as realizing the first sale and

reaching profitability (Uzzi, 1997; Davidsson and Honig, 2003). The more social

relationships the start-up possesses, the faster the entrepreneurs should be able to access

necessary resources. Social networks act as fast entrance ticket to an industry (Lechner and

Dowling, 2003). Large family and friends networks should therefore affect firm

performance positively (Johannisson, 2000). Founders personal networks at the start of

the firm have also been associated with growth (measured as number of employees) in the

subsequent year (Hansen, 1995) as well as social capital in the pre-start-up phase with

initial success such as the first sale (Lechner and Dowling, 2003). Therefore, their initial

size should influence growth (Zhao and Aram, 1995; Baum et al., 2000).

Hypothesis 2. The number of social network ties at foundation will reduce the time

needed to reach performance targets.

However, some researchers have argued that the quality of relationships, often

depending on the founders context, will influence firm performance (Ostgaard and Birley,

1994). Over-reliance on social networks, for example, could cause problems after the startup phase. First, while social networks give certain, low-cost, rapid access to resources, the

number of appropriate social ties that are beneficial for the requirement of the business

might be limited. There may be diminishing marginal returns for adding new relationships

(Deeds and Hill, 1996). A software entrepreneur reported in a study by Lechner and

We would like to thank Howard Aldrich for this distinction during a personal communication.

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

521

Dowling (2003): bAt the beginning, we only teamed up with friends but how many friends

can you have? Sometimes friends were not the right partners for the job requirementQ (p.

11). Second, networks can give access to different resources such as financial, information,

or help in finding first customers or suppliers. Social network analysis has shown that

strong ties are often characterized by high similarity and that strong relationships between

one focal actor with two other members of a network tend to lead to at least one weak tie

between the two other actors (Granovetter, 1974; Burt, 1992). Structural hole theory (Burt,

1992, 1997) has stressed the benefits of brokerage opportunities that are created by the

lack of connection between third parties.4 Since social networks are strong ties, the

information gathered from one member of the network might be rich, but the information

gathered from all members of this network might be redundant. Third, besides quality and

redundancy issues, large social networks can have an additional negative effect on

subsequent firm performance. Structural hole theory also suggests that a lack of structural

holes in the network of a focal actor not only reduces the diversity of resources accessible

but also the actors autonomy to engage in new relations (Burt, 1992, 1997). This

phenomenon of social over-embeddedness could eventually lead to a growth barrier (Uzzi,

1997; Gargiulo and Benassi, 2000). Social networks, while important for the establishment

of the firm and for reaching first milestones (Johannisson, 2000), may not be sufficient for

subsequent firm development (Lechner and Dowling, 2003). As a consequence, other

types of networks should become more important after start-up (Dollinger, 1985; Green

and Brown, 1997). These existing networks could subsequently be transformed into richer

and more complex networks (Larson, 1991, 1992; Dubini and Aldrich, 1991) to enable

firm development. It has been, however, argued that the decreasing importance of family

and friends networks is more implicit that explicit in most research (Cooper, 2002).

Therefore, if we compare firms and their networking behavior in subsequent years, other

networks should become more important for firm performance.

Hypothesis 3. The number of social network ties will be negatively associated with firm

performance in the years after foundation.

3.3. Reputation networks

Larson (1992) has suggested that social networks and reputation were pre-conditions

for economic exchange. Therefore, relationships with other firms can have important

reputational or signaling effects (Stuart et al., 1999; Gulati and Higgins, 2003; Deeds et al.,

2004). We define reputational networks as ties with firms where entrepreneurs estimated

that the main reason for entering into the relationship was to gain reputation. Reputational

networks consist of ties with prominent firms and individuals such as well-known venture

capital firms, leading firms in a given market, or highly reputed customers. However, to

enter into reputational relationships, entrepreneurial firms must be able to offer attractive

resources (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven, 1996). But even excellent resources may not

The lack of connection between two actors B and C, who are both connected to an actor A, is called a

structural hole and is the basis of structural hole theory (Burt, 1992).

522

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

suffice to overcome the reluctance of firms to engage into exchange relationships with

very young firms since economic exchange with these firms is perceived to be risky

(Bhide, 2000). Gaining reputation is an effective means of overcoming liability of newness

and increasing firm performance (Larson, 1992; Gulati and Higgins, 2003; Roberts and

Dowling, 2002).

Industries can be understood as a community with credible and reputable firms.

Affiliation with one of these firms increases the reputation of the start-up company and

should therefore be considered a corporate goal. Reputation leads to social and economic

trust in capabilities (Larson, 1992), and reputational networks can replace experience and

the lack of a track record (Stuart et al., 1999): b. . .the impact of inter-organizational

relations is driven more by who a company is associated with than by the volume of its

relations (Stuart et al., 1999, p. 345). Increased reputation should facilitate the access to

other stakeholders such as suppliers and clients who are willing to engage with the young

firm since the perceived risk of an exchange relationship is lower. As a consequence, the

existence of reputational partners should facilitate selling products. Therefore, entrepreneurial firms that build reputational networks early on should reach performance targets

faster. In later phases, the firm will need fewer reputational networks as it develops its own

reputation. In addition, with growing size, firms tend to integrate activities and reduce the

number of inter-firm relationships (Rothaermel and Deeds, 2001). Overall, reputational

networks should accelerate the development of start-ups through the creation of options

for developing more and richer relationships in the future (Larson, 1992; Lechner and

Dowling, 2003). Reputational networks were proposed to influence firm growth (Lee et

al., 2001) and to reduce the time to reach performance targets such as time-to-IPO (Stuart

et al., 1999). The existence of reputational networks at the start of a firms life cycle should

therefore reduce the time needed to reach performance targets such as realizing the first

sale, realizing a certain sales volume, or reaching break-even. A lack of reputational

networks should slow down firm development (i.e., lengthen the time needed to reach

performance targets). In this sense, the opportunity to gain reputation partners is, first, the

outcome of firm capabilities and resources. Second, the active cooperation with

reputational partners is an important form of networking. The resulting network influences

as a consequence firm performance.

Hypothesis 4. The number of reputational network ties at foundation will reduce the time

needed to reach performance targets.

3.4. Co-opetition

Co-opetition networks involve relationships with direct competitors. The management

literature generally considers industries to be collections of firms bound together by

rivalry, therefore questioning the value of relationships with competitors (Dollinger, 1985).

Particularly technology alliances with competitors are supposed to harm firm development

(Baum et al., 2000). However, it has been argued that relationships with competitors can

help entrepreneurs towards a better understanding of their firm context and opportunities,

thus influencing firm performance (Dollinger, 1985). Co-opetition (i.e., cooperation

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

523

between competitors) seems to be a widespread phenomenon of entrepreneurial firms

(Dowling et al., 1998). Firms can use competitors as subcontractors in times where the

firm has temporarily reached full capacity. This cooperative behavior, especially with

regional competitors, will increase the likelihood of the favor being returned. Moreover,

firms can form alliances with competitors in order to handle large projects. Overall,

relationships with competitors can give access to temporarily needed resources or lead to

the temporary pooling of resources, which should positively influence firm performance

especially in the years after foundation, when sales tend to grow discontinuously (Lechner

and Dowling, 2003). While it has been argued that co-opetition networks at foundation

might be harmful because such relationships could lead to the disclosure of competitive

information (Baum et al., 2000), lack of co-opetition networks can also constrain firm

development in the years following foundation. Entrepreneurial firms that view

competitors not only as pure rivals but also as a potential resource should therefore be

more successful (Lechner and Dowling, 2003).

Hypothesis 5. The number of co-opetition networks will positively influence performance

in the years after foundation.

3.5. Marketing information networks

Marketing information networks are relationships that allow for the flow of market

information through distinct relationships with other individuals/firms. Marketing

networks are useful for informal environmental scanning while marketing research is

based on formal environmental scanning. Research on marketing planning in large firms

has, in general, shown a positive relationship between formal marketing planning and firm

performance, but its usefulness was questioned for small firms that favor personal and

informal environmental scanning (Brush, 1992). Customers have also been shown to be an

important input for the development of innovations (Von Hippel, 1978; Malecki and

Poehling, 1999). In addition, suppliers, competitors, and distribution channels are valuable

information sources (Dollinger, 1985) that can influence strategy-making in entrepreneurial firms (Ostgaard and Birley, 1994). Family and friends networks are perceived as of

little value for marketing information (Brush, 1992). It has been argued that marketing

information networks are associated with an open management style in which the

responsibility for networking is an important function for all employees (Lechner and

Dowling, 2003) since marketing networks can be considered an outcome of network

complexity (Larson and Starr, 1993; Lorenzoni and Lipparini, 1999; Hite, 2000). This

means also that relationships with other firms develop only over time into marketing

networks. First clients with whom a firm had developed a simple exchange relationship

become real partners over time. Clients or suppliers of new firms can increase their

commitment over time with the new firm since they have a stake in its survival (Bhide,

2000). Customers become dlead usersT only through learning-by-using, which implies

some path dependency (Von Hippel, 1978). In addition, it seems that start-ups have only a

few important clients at the beginning, which serve later on as referrals (Lechner and

Dowling, 2003). Marketing information networks should therefore positively influence

firm performance in the years after foundation, suggesting that external marketing

524

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

information networks are more important than an internal marketing planning function

(Brush, 1992; Malecki and Poehling, 1999).

Hypothesis 6. The number of marketing information network ties will positively influence

firm performance in the years after foundation.

3.6. Cooperative technology networks

Cooperative technology networks are relationships with other firms in order to jointly

develop technology for the creation of innovation. Initially, start-up companies often lack

the reputation and resources to enter into cooperative technology networks with other

firms (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven, 1996; Ahuja, 2000). It seems also that start-ups

initially exploit their own technology base before entering into cooperative technology

networks (Lechner and Dowling, 2003). Because they are time- and resource-intensive,

cooperative technology networks should be developed after the start-up phase but before a

firms maturity. Building technology portfolios has been shown to be a way to foster

alliance formation, which in turn influences the firms innovation rate and therefore leads

to the continuous development of the entrepreneurial firm beyond its original technology

portfolio (Kelley and Rice, 2002).

However, technology partnering is a costly and time-intensive form of inter-firm

collaboration. The nature of this type of relationships limits the extensive use of this type

of relationship. In fact, a curvelinear relationship between the size of cooperative

technology networks and new product development was demonstrated in the study by

Deeds and Hill (1996). Nevertheless, we believe the advantages of technology cooperation

will still positively affect firm performance.

Hypothesis 7. The number of cooperative technology network ties will positively

influence performance in the years after foundation.

4. Methods

4.1. Sample and survey design

The hypotheses were tested using data from a pre-tested survey sent to CEOs and

founders of VC-financed firms in German-speaking countries in 2003. Since there was no

comprehensive database on VC-financed companies in Germany, Switzerland, Austria,

Liechtenstein, and Luxembourg, over a period of 6 months, we developed a database

identifying 1453 VC-backed companies in these countries. In a first step, data of the

German Venture Capital Association and the European Venture Capital Association were

accessed, leading to 182 VC firms, which should cover about 90% of venture capital firms

in German-speaking countries. We discovered other 47 venture capital firms via lists of

other German researchers, business plan competitions, and personal networks. In a second

step, available material on these VC firms concerning their portfolio firms was analyzed,

and the VC firms were contacted directly for information on portfolio companies. Based

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

525

on this information, we compiled a list of firms that had received venture capital in these

countries. We only considered VC-financed companies that were still actively managed

(i.e., they had to have venture capital money under management). We also excluded firms

that had received growth-stage and late-stage financing (controlled additionally by a

question in the survey) but concentrated on seed and early-stage financing. We estimate

that the firms cover about 80% of the entire population of VC-backed companies with

these characteristics5 and that the database is representative since it does not contain any

systematic omission errors.

A survey was the most appropriate means of collecting data because secondary

resources did not contain detailed information regarding network types, network size,

attitudes towards networking, etc. (Davidsson and Wiklund, 2000). Therefore, all

information, network, and performance data were self-reported, but previous research

gives support to the reliability and validity of self-reported measures (Brush and

Vanderwerf, 1992; Orpen, 1993), especially if other sources are unavailable, as in the

study of young and privately held small firms (Dess and Robinson, 1984). To ensure that a

high proportion of the answers was valid, the questionnaires were sent to the CEOs and/or

founders of the start-ups, using a key informant approach (Huber and Power, 1985; Brush

and Vanderwerf, 1992; Chandler and Hanks, 1993): CEOs and founders are considered the

single most knowledgeable and valid information sources (Hambrick, 1981; Vanderwerf

and Brush, 1989; Glick et al., 1990). We are, of course, aware of the trade-off between

objective data collected from secondary sources at several different times and data richness

derived from primary sources; given the unavailability of sufficient data, we therefore had

to opt for a survey approach of self-report data (Davidsson and Wiklund, 2000; Lyon et al.,

2000).

Following Vanderwerf and Brushs (1989) recommendations, we restricted the sample

firms in the following way. The firms were less than 10 years of age, which is consistent

with research on entrepreneurial firms (Covin et al., 1990). The average age of the firms in

our sample of 5 1/2 years comes close to the stricter recommendations of other researchers

(Robinson, 1999; Zahra et al., 2000). Founding management had to still be with the firm

(Robinson, 1999). To be able to measure performance effects, we also excluded firms that

reported zero sales for all years of data collection. The choice of VC-backed firms was

driven by different considerations. In our opinion, the restriction might dampen industry

effects that are typical in strategic management research (Dess et al., 1990), since VCs in

Europe particularly invest in attractive industries and therefore we assume minor industry

effects across industries. Moreover, the selection of these firms acts as a form of control of

founding conditions that renders the start-up base of the firms more homogeneous except

for network composition (Baum et al., 2000). Additionally, VC-backed firms are not

subject to corporate sponsorship and can therefore be considered independent entrepreneurial ventures (Robinson, 1999).

The questionnaire was sent to a random sample of 570 firms in the developed database.

A total of 142 questionnaires (i.e., about a quarter of the questionnaires returned) came

This estimate is based on the analysis of Finance magazine (Finance Magazin, February 2002) and an

approximation given by the Bundesverband Deutscher Kapitalgesellschaften (BVK).

526

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

back because the firms had gone out of business, reducing the effective sample to 428

firms. Of the 75 questionnaires received, 60 met all sample selection criteria and were

sufficiently completed. This translates to an effective response rate of 14%, which can be

considered acceptable given that the average age of the firms was only about 5 1/2 years.6

The final sample therefore consisted of 60 VC-financed start-ups, which had to be less

than 10 years old, had a sales track record, and were located in one of the countries

mentioned above. Sample firms come mainly from the IT, services, media, bio-tech, and

environmental industries.

5. Measures

5.1. Dependent variables

A difficult decision in entrepreneurship research is the choice of performance measures.

There are no commonly accepted performance measures for new ventures (McGee and

Dowling, 1994). We used both time-to-break-even and sales as performance measures.

Reaching break-even can be considered one of the firms basic goals and therefore an

adequate performance measure for start-ups (Davidsson and Honig, 2003). Respondents

were asked when they had reached break-even (months after foundation), or when they

thought they would reach break-even (in months). For those who had not yet reached

break-even, time-to-break-even was calculated by adding their estimates to the age of the

firm (recorded in months). Davidsson and Honig (2003) studied pre-venture endowments

in the form of social and human capital and their effect on business outcomes by applying

a time measure of performance (manifestation of first sale/profitability 18 months after

foundation). While they use a nominal measure (yes/no) at time intervals, we determined a

real time measure for moving into the profit zone (time-to-break-even in months).

Gatewood et al. (1995) also applied a time measure for the influence of start-up behavior

and success. Teach et al. (1989) also used the variable time-to-break-even as a

performance measurement in order to evaluate the discovery of new venture ideas on

performance. Overall, it seems that time measures are particularly appropriate for

measuring effects of pre-start-up and start-up endowments or activities and firm

performance. The use of a time measure seems to us both reasonable and important

especially when measuring the effect of initial network endowments, since other research

on inter-organizational relations has underlined the importance of speed to reach

performance targets (Stuart et al., 1999).

To measure network effects on firm performance in the years after foundation, we used

a 1-year time lag between networks and sales. We chose sales and not sales growth

because of possible distortions due to minimal or non-existent sales at the beginning of the

firms existence. Sales volume and sales growth are a common performance measure

especially for small and young firms (Begley and Boyd, 1986; Cardozo et al., 1996; Rue

McDougall et al. (1994), for example, reported a 11% response rate and Chandler and Hanks (1993) reported

a 19% response rate.

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

527

and Ibrahim, 1998; Weinzimmer et al., 1998; Robinson, 1999; Lebrasseur et al., 2003;

Delmar et al., 2003) and are arguably a sufficient single indicator for firm performance

(Venkatraman and Ramanujam, 1987; Delmar et al., 2003). Sales are relatively insensitive

to capital intensity and degree of integration, and therefore an appropriate measure for

studying networks even if they are sensitive to inflation (Weinzimmer et al., 1998; Delmar

et al., 2003). In addition, the relatively low inflation rate during the period of interest in the

countries concerned does not call for a particular control for inflation.

Since many researchers expect a causeeffect relation between networking activity,

network composition, and firm performance (Birley, 1985; Aldrich and Zimmer, 1986;

Dubini and Aldrich, 1991), we thought that some form of time lag was conceptually

important for our study: entrepreneurs develop networks not only as a response to

immediate needs but for future use (Johannisson, 2000). In line with other research, we

used an 1-year time lag between network size or relational mix and sales (i.e., we

compared the independent variables in t 0 with sales in t 1). In their study, Lebrasseur et al.

(2003) used a 1-year time lag between start-up activities and sales in the subsequent year.

Lee et al. (2001) compared sponsorship-based linkages and performance in the subsequent

2 years. Hansen (1995) and Chrisman and McMullan (2000) compared the entrepreneurs

support networks with organizational growth measured as employees and amount of

payroll in the subsequent year, therefore also applying a 1-year time lag.

In summary, we used time-to-break-even as a time measure of performance at

foundation and sales as performance measure in the years after foundation.

5.1.1. Model specifications

We tested two main models according to our hypotheses using OLS regression. In

both models, we compared the explanatory power of a control model using network

size only with a sub-model using the relational mix. We are aware that some research

(e.g., Deeds and Hill, 1996) has demonstrated a curvelinear relationship between

specific network types (technology partnering) and specific forms of intermediary

performance (new product development). The arguments against a simple linear

relationship between networks and overall firm performance are costs, benefits, risks,

and relational capability over time (Deeds and Hill, 1996; Pihkala et al., 1999;

Lechner and Dowling, 2003). Limited relational capability might eventually lead to

integration of some activities or restructuring of the existing network (Lorenzoni and

Ornati, 1988; Delmar and Davidsson, 1998; Lechner and Dowling, 2003; Rothaermel

and Deeds, 2001). We made the assumption that the firms in our sample were not

yet affected by diminishing returns of inter-firm relationships because of their young

age (Rothaermel, 2001).

In the first model, we tested the influence of networks at foundation on time-to-breakeven. The independent variables were network size and the relational mix in the first full

year of the firms existence. We had actual registration dates of the company foundation

and therefore decided to take the first full year of existence as the start-up point (i.e., the

first year in which the company existed effectively for 12 months), since the fact, that

some companies have existed only for 2 or 3 months in the first year registered, would

have strongly biased the results.

528

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

In the second model, we tested the influence of networks on firm performance after

foundation. We calculated networking years for this purpose in order to gain a better

understanding of the role of networks in the years after foundation. This method gave a

richer and more consistent data set (Baum et al., 2000) instead of taking firms of different

ages and their last years networks, which would actually mean using networking years

without being able to control for some form of evolution. We had asked the firms to

indicate different network types at the start of the firms existence and for the 5 years

following. For this model, we did not use firms as observations but the networking years

24, leading to 159 cases. We added the age of the firmmeasured in monthsas a control

variable.

5.2. Independent variables

The important independent variables of interest were the cumulative number of different

types of inter-firm relationships. We defined partners, in general, as those active relationships

with other firms that go beyond the simple exchange function. We measured number of

network ties for the variables below by counting the number of direct relationships.

5.2.1. Overall network size

The respondents were asked specifically to indicate the total number of relationships

that they regarded as important for their business, independent of the value of economic

exchange. Network size was therefore the cumulative number of all active inter-firm

relationships that were instrumental for the business.

5.2.2. Social networks

We defined social networks as strong personal relationships with members of other

firms or stakeholder before the founding of the firm based on social relationships with

individuals, such as friends, relatives, long-standing colleagues who have become friends,

and so forth. Respondents were asked to indicate how many of these active and strong

relationships they have had before starting the company.

5.2.3. Reputation networks

Reputation partners are firms that are market leaders or highly regarded firms that can

give reputation or legitimacy to the young firm. Respondents were asked to give the

cumulative number of relationships where the main objectives was to enter into such

relationships to increase the entrepreneurial firms credibility.

5.2.4. Co-opetition networks

Co-opetition networks were defined as relationships with direct competitors. Different

types of relationships were possible: competitors used as sub-contractors, being a subcontractor of the competitor, competitor as partner to respond to call for tenders, or

competitor as an important source of information. The variable measured the cumulative

number of all these types of relationships with competitors.7

7

We did not use the different co-opetition relationships in this study but aggregated the data.

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

529

5.2.5. Marketing information networks

Marketing information networks are those relationships with other firms that lead to

information about market opportunities. They fall into the following categories: (1) the

other firm is an important source of information concerning products, markets, or clients;

(2) the other firm serves as referral in order to establish contact with a new client; and (3)

the other firm helps to better tailor a product or service to market needs. Market

information networks is a count variable.

5.2.6. Cooperative technology networks

Cooperative technology networks were defined as the number of technology alliances

such as joint research and/or development projects, licensing, and cross-licensing

agreements.

5.2.7. Measurement of the relational mix

The relational mix is made up of social, reputation, co-opetition, marketing

information, and cooperative technology networks. The measurement of the relational

mix poses a methodological and practical problem, since there may be double counting or

overlap of different network types in one relationship. A firm might serve as a member of

both a firms reputational network and its co-opetition network, and even be part of the

firms cooperative technology network later. Marketing information might come from a

social network member for a week, a technology collaborator the next week, and

reputational network company the week after. We acknowledge this problem, but prior

case study research suggests that entrepreneurs can distinguish between value-adding

relationships and all other relationships with other firms (Dubini and Aldrich, 1991).

Second, entrepreneurs can identify the relationships they consider to be most important

(Larson, 1992). Third, in a given time period, entrepreneurs tend to label their economic

exchange partners and classify them according to the main benefit that the partner provides

(Lechner and Dowling, 2003). Despite possible overlaps, networks can be analysed with a

rational-choice framework (Johannisson, 2000). In the pre-test of the questionnaire, we

received various comments in this sense (e.g., bFirm A, one of our suppliers, adds value to

our business by giving us timely information about market trends; we regard A mainly as a

market informant; Firm B, one of suppliers, co-develops product solutions with us, they

are a real innovation partner,Q etc.). Obviously, the importance or the main benefit of one

actor can change over time. While we cannot control in our study whether entrepreneurs

added new ties to develop different kinds of relationships or if they were able to transform

relationships according to new priorities, we can provide a snapshot about the types of

relationships used at a point in time. The lack of auto-correlation of the independent

variables seems to support our assumption. Additionally, one would expect the number of

total relationships reported by the firms to be smaller than the sum of the different network

types if double counting were an important methodological problem. The results, however,

showed that the total number of important relationships reported was slightly higher than

the sum of the relationships of the different network types. This can indicate that the

respondents were able to classify most of their relationships according to a specific

function and therefore as specific network type while only a small fraction of relationships

was difficult to classify.

530

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

5.3. Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the sample in general, for networks in the first

full year of existence, and for the subsequent years. The 60 firms have, on average, a timeto-break-even of 53 months. As expected, social networks are the most numerous

networks. The number of social networks and the overall size of networks are consistent

with other research (Aldrich, 1999; Dodd and Patra, 2002). Sales ranges and their

development show that this is a sample of growth firms.

6. Results

6.1. The importance of the relational mix at foundation

As discussed above, with partial model 1b (Table 2), we tested the influence of the

relational mix at foundation on time-to-break-even. The model was significant, with

moderate explanatory power. DurbinWatson statistics and collinearity statistics were also

acceptable. In this model, social and reputation networks had negative coefficients as

expected (i.e., they reduce the time-to-break-even but only reputation networks had a

significant influence on time-to-break-even; p = 0.03). Hypothesis (2) is therefore not

supported but Hypothesis (4) is supported. Surprisingly, technology networks showed a

positive coefficient and the relationship was weakly significant ( p = 0.09), indicating that

early technology partnering delays reaching firm performance targets.

6.2. The importance of the relational mix on firm performance in the years after

foundation

Table 3 presents the OLS regression for the partial model 2b. As already discussed, this

model is significant ( p b 0.001) with a relatively high explanatory power (adjusted

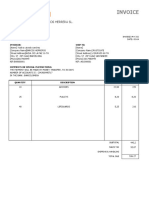

Table 1

Descriptive statistics

Average time-to-break-even (months)

Number of firms

53.18

60

Networks in year 1 (mean)

Networks in years 24 (mean)

Social networks

Reputation networks

Co-operation networks

Marketing information networks

Technology networks

6.57

2.80

0.84

2.64

1.34

8.51

4.47

2.40

5.25

2.19

Sales data in year 1

Sales data in years 25

1,582,642

1,000,000

015,000,000

4,608,141

1,600,000

30,00080,000,000

Average sales (in o)

Median (in o)

Range (in o)

531

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

Table 2

OLS regressionnetworks at founding

Model 1

Dependent variable: time-to-break-even (in months)

Model 1a: network size

Model 1b: relational mix

Standardized regression coefficients (significance)

Intercept

(0.000)

(0.000)

Research variables

Network size

Social networks

Reputational networks

Co-opetition networks

Marketing networks

Technology networks

Adjusted R 2

F

df

DurbinWatson

n

!0.223 (0.087)

0.003 ( p b 0.087)

3.0346

1/58

2.06

60

!0.218 (0.139)

!0.298 (0.029)*

0.011 (.936)

!0.069 (0.627)

0.214 (0.093)

0.123 ( p b 0.032)

2.658

5/54

1.87

60

OLS regressionnetwork size at founding (first full year of existence) and time-to-break-even versus relational

mix at founding (first full year of existence) and time-to-break-even.

R 2 = 0.39); the DurbinWatson coefficient of 1.61 was especially positive considering that

we tested network years against sales and not individual firms. Collinearity statistics were

quite strong. In this model, the control variable age did not have a significant influence on

Table 3

OLS regressionnetworks after founding

Model 2

Dependent variable: sales (in o) lagged by 1 year

Standardized regression coefficients (Significance)

Intercept

Controls

Age

Research variables

Network size

Social networks

Reputational networks

Co-opetition networks

Marketing networks

Technology networks

Adjusted R 2

F

df

DurbinWatson

n

Model 2a: network size

Model 2b: relational mix

(0.095)

(0.368)

0.167 (0.035)

0.073 (0.217)

0.213 (0.007)

0.074 ( p b 0.001)

7.149

2/153

1.67

159

!0.147

0.168

0.508

0.208

0.058

0.389

17.459

6/149

1.61

159

(0.043)*

(0.020)*

(0.000)*

(0.006)*

(0.370)

( p b 0.001)

OLS regressionnetwork size in the years after founding (years 24) and sales in the following year versus

relational mix and sales in the following year.

532

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

sales. Co-opetition and marketing information networks had a significant and the strongest

influence on sales in the years after foundation. Hypotheses (5) and (6) are therefore

strongly supported. As expected, social networks had a negative impact on sales.

Hypothesis (3) is therefore supported. Reputation networks had a moderate effect on

sales. Cooperative technology networks had no relevant and significant influence on

sales. Hypothesis (7) is therefore not supported.

6.3. Relational mix versus network size

One of the goals of this study was also to compare performance effects of the network

size (i.e., the total number of relationships with other firms) versus a more fine-grained

measurement (i.e., different network types and their mix). Therefore, two main OLS

regression models were tested, with total network size and the relational mix as

explanatory variables for firm performance measured in model 1 by time-to-break-even

and in model 2 by sales. In model 1 (Table 2), we used the individual firms as cases

(n = 60) and tested the size of networks in the first full year of existence against time-tobreak-even. Descriptive statistics showed that overall time until break-even was rather

long (mean = 53 months, or almost 4 1/2 years). Model 1a with network size alone had

weak explanatory power and was only significant at the 0.10 level. Therefore, we conclude

that network size at founding, at best, weakly influences time-to-break-even. The model

using the relational mix (model 1b), on the other hand, was significant, with moderate

explanatory power (adjusted R 2 = 0.12, p = 0.032). Therefore, we can conclude from the

results of models 1a and 1b that the relational mix is more effective in explaining

performance at foundation than network size only.

In model 2 (Table 3), we tested the role of network size and relational mix in the years

after foundation (years 24) on the following years sales with firm age as the control

variable. Model 2a was significant but with relatively low explanatory power (adjusted

R 2 = 0.074, p b 0.001). Age as a control variable and network size had a positive and

significant influence on sales. The model therefore showed a firms network size to have a

very moderate influence on a firms development (measured in sales). However, the

second partial model, model 2b, which tested the influence of the relational mix on sales,

was a better explanatory model. The overall model was significant and demonstrated a

much higher explanatory power than network size model (adjusted R 2 = 0.39).

Overall, we conclude that network size is moderately linked to firm performance, and

the relational mix is a better explanatory concept than network size for firm performance at

and beyond foundation.

7. Discussion

The objective of this study was to empirically test the importance of the relational mix

on entrepreneurial firm development. The tested models demonstrated that the relational

mix has a higher explanatory power than network size alone. There was a positive and

significant relationship between reputation networks at start and a shorter time-to-breakeven. On the other hand, there was a negative relationship between early technology

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

533

networks and time-to-break-even, meaning that technology networks may actually delay

achieving break-even. These findings are consistent with the model of Lechner and

Dowling (2003). Gaining reputation can be considered an important means of gaining

legitimacy with positive signaling effects to the markets of resource providers (Stuart et

al., 1999; Roberts and Dowling, 2002; Deeds et al., 2004). Our analysis suggests that

reputation networks also play a moderate role after the start-up phase, meaning that

reputational networks remain positively associated with firm development. Concerning

technology networks, it seems that firms use their initial technology base to exploit a

business opportunity and that technology partnering is a means to enhance the technology

platform later on to prepare the company for the future (Kelley and Rice, 2002). Early

technology partnering might therefore be an indicator that firms are not yet ready to

exploit business opportunities or not attractive enough to enter into more value-adding

partnerships (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven, 1996). Somewhat surprising was the nonsignificant relationship between social networks and time-to-break-even. Social networks

are considered an important start-up resource of the entrepreneurial firm (Johannisson,

1995; Zhao and Aram, 1995; Baum et al., 2000). Our study did show that social networks

are the firms largest networks at the start of its existence (mean = 6.57 in the first full year

of existence, whereas every other network type contained no more than three relationships). It may be that since social networks are the start-up base for almost all firms, that

they are not a good discriminator of successful firm development. It is also possible that

social networks are more important at the critical stage of pre-foundation when

entrepreneurs assemble their very first resources and have some initial level of financial

backing and a small number of customers and suppliers, but not when firms are already

focusing on sales growth and time-to-break-even. The literature on nascent entrepreneurship seems to support this position (Aldrich, 1999; Davidsson and Honig, 2003). Social

networks seem to have an indirect effect. The quality of social networks can be very

different and the use of social networks might also make a difference. The negative and

significant influence of social networks on sales after foundation, however, was expected

and confirmed, supporting the view that social networks move into the background as

other types of networks emerge to support the growth of the firm. A high dependence on

social networks over time could be considered an indicator that firms are not capable of

developing other important ties. It might also indicate a tendency towards overembeddedness (Gargiulo and Benassi, 2000). Our analysis demonstrated the significant

and positive influence of co-opetition and marketing information networks on sales after

the start-up phase. Our findings therefore support other research that underlines the

importance of external and informal marketing information scanning instead of a more

formal marketing approach for young firms (Brush, 1992). Little is known, however, about

how firms develop marketing networks. It has been suggested that marketing networks are

a function of management style and open firm culture, and therefore a task of all

employees (Lechner and Dowling, 2003). In contrast, it has been argued that networks are

developed mainly by the entrepreneurial team at the beginning of the firms life cycle

(Ostgaard and Birley, 1994; Johannisson, 1995; Lipparini and Sobrero, 1997). Concerning

the importance of co-opetition networks, the analysis of the survey data suggests that of

those firms that had relationships with other competitors, about one third was using

competitors as subcontractors and receiving subcontractor jobs from competitors as well as

534

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

carrying out large projects together with competitors. Co-opetition networks seem to

increase the entrepreneurial firms flexibility and to promote sales growth after the start-up

phase. Our analysis was not able to demonstrate a relationship between technology

networks and sales development after foundation. As expected, technology networks are

rather small in number (mean = 1.87 over all networking years), which might explain the

low relevance in the overall model. Other research also suggests that the building of

technology networks has more of an indirect effect on firm performance (Kelley and Rice,

2002) and results might only be revealed in the long run. The time frame of our study

might not have been sufficiently broad to test the influence of technology networks on firm

development.

In general, our study emphasizes the importance of the relational mix and the change of

the relational mix on firm development. This result supports the perspective in

entrepreneurship research that many factors interacting in a complex way in a dynamic

context determine firm development (Shane and Venkataraman, 2000). The study

questions further the use of overall network size as a simple measure.

We acknowledge several limitations to our research. We have already addressed the

question of self-reported data. We cross-checked the financial data randomly for

consistency through press releases issued on the websites of 12 companies. This research

was limited to venture capital-financed firms and therefore to high-tech firmsnonventure capital-financed firms may experience different constraints (especially of a

financial nature). We see this limitation more as a strength since networking has been

associated with lack of resources and we were able to demonstrate the link between

networking and firm development of less constrained firms. The selection of these firms

acts as a form of control on foundation conditions that renders the start-up base of the

firms more homogeneous except for network composition (Baum et al., 2000). This

approach finally led to an initial homogenous group of firms, reducing the bias of crossindustry analysis. However, given the selection process of VC firms, our sample might

naturally have a growth bias. Moreover, we did not include regional effects in our model.

It is suggested that the development of egocentric networks depends on larger sociocentric or regional networks and vice versa, as can be found in regional clusters

(Johannisson, 1998; Lechner and Dowling, 2000). Therefore, we did not control for sparse

regions or industries (i.e., regions or industries where networking was difficult because of

the lack of partner firms) (Dubini, 1989; Davidsson, 1995). However, other research

suggests that entrepreneurs in sparse regions try to establish relationships with other firms

outside their original location (Birley and Westhead, 1990). In addition, our sample did not

have any systematic regional bias due to the construction of the overall population.

Another argument concerns possible signalling effects due to the fact that the firms are

VC-backed. Venture capital firms may also facilitate access to other reputational partners.

However, this does not explain intra-sample differences. Concerning reputation networks,

we mentioned above that reputation networks can be the outcome of excellent resources

and that these excellent resources explain firm performance. While we cannot control for

this reverse causality in the model, we argue based on case study research (Lechner and

Dowling, 2003) that excellent resources without reputation networks are not sufficient to

overcome liability of newness. In this study, we did not measure network structure (i.e.,

neither indirect ties nor non-redundant ties). The influence of measures such as direct

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

535

network size is particularly heavily constrained by the efficiency of the overall network.

Replication with an ever larger sample would, of course, be desirable.

8. Conclusions

Networking is very important for entrepreneurial firms. This study supports the view

that entrepreneurial networking is as much about adding new and different relationships as

about transforming existing relationships, therefore empirically supporting case-based

research in the field (Larson, 1992; Dubini and Aldrich, 1991; Lechner and Dowling,

2003). This study has both theoretical and practical implications. Complex development

models are still rare in entrepreneurship research (Hoang and Antoncic, 2003). This study

addresses the area with a specific aspect of networking (i.e., the role of the relational mix

on firm development). We think that our findings advance research because they

demonstrate that the complex measure of the relational mix provides more explanatory

power than previously used measures such as network size. Second, it underlines the

importance of different networks in different situations (Gulati and Higgins, 2003). We

believe that more development-oriented and detailed network studies are needed to

enhance our understanding of the complex development processes of entrepreneurial

firms. Both quantitative and qualitative studies investigating network structure efficiency

through network mapping over time would lead to new insights and propositions to further

research on networks in entrepreneurial firms. Additionally, we lack knowledge about how

to develop certain network types and think that studies linking management style and

networking could produce promising insights.

From a practical perspective, understanding network dynamics helps answer the

question of which ties matter when. Young firms that are constrained by liability of

newness should use their social networks to develop early reputation networks to foster

firm development. Our study also showed that marketing information networks play an

important role in firm development. External and informal marketing information scanning

seems not only to be a necessity for young firms because of resource constraints but also

an effective means of detecting and exploiting market opportunities instead of a more

formal approach to marketing. Furthermore, the study revealed the importance of

relationships with competitors for firm development. While it is not an easy decision for an

entrepreneur, our research suggests that there are true benefits to entering into a

relationship with a competitor. Finally, technology partnering seems to be a means of

enhancing the technology platform of the firm and to be more important at a later stage of

the firms development. Overall, our study suggests that networking should be a proactive

task of entrepreneurs and that strategic network building over time is an important factor

for the development of the entrepreneurial firm.

References

Ahuja, G., 2000. The duality of collaboration: inducements and opportunities in the formation of interfirm

linkages. Strategic Management Journal 21/3, 317 344.

536

C. Lechner et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2006) 514540

Alba, R.D., 1982. Taking stock of network analysis: a decade of results. In: Bachran, S.B. (Ed.), Research in the

Sociology of Organizations, vol. 1. JAI, Greenwich, CT.

Aldrich, H., 1999. Organizations Evolving. Sage, London.

Aldrich, H., Zimmer, C., 1986. Entrepreneurship trough social networks. In: Sexton, D., Smilor, R. (Eds.), The

Art and Science of Entrepreneurship. Balliner, New York, pp. 3 23.

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., 2000. A model of the opportunity recognition process. Journal of Enterprising

Culture 8 (2), 103 119.

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., Ray, S., 2003. A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and

development. Journal of Business Venturing 18 (1), 105 123.

Baum, J., 1996. Organizational ecology. In: Clegg, S., Hardy, C., Nord, S. (Eds.), Handbook of Organization

Studies. Sage, London.

Baum, J., Calabrese, T., Silverman, B., 2000. Dont go it alone: alliance network composition and startups

performance in Canadian biotechnology. Strategic Management Journal 21 (3), 267 294.

Begley, T., Boyd, D., 1986. Executive and corporate correlates of financial performance in smaller firms. Journal

of Small Business Management, 8 15 (April).

Bhide, A., 2000. The Origin and Evolution of New Businesses. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Birley, S., 1985. The role of networks in the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing 1,

107 117.