Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Grading - This Topic, Even More That Academic Dishonesty, Is Often Treated As A Separate Area. Given

Загружено:

imherestudying0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

7 просмотров1 страница4

Оригинальное название

4

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документ4

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

7 просмотров1 страницаGrading - This Topic, Even More That Academic Dishonesty, Is Often Treated As A Separate Area. Given

Загружено:

imherestudying4

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 1

actually do not know what constitutes plagiarism.

We owe it to the students to explain what is

considered to be plagiarism or cheating.

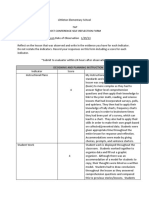

Grading -- this topic, even more that academic dishonesty, is often treated as a separate area. Given

the students' interest in graded, such treatment is certainly defensible. Each syllabus should include

details about how the students will be evaluated -- what factors will be included, how they will be

weighted, and how they will be translated into grades. Information about the appeals procedures,

often included in a student handbook, is also appropriate at least for freshman and sophomore

classes.

Available Support Services. Most college courses have available to the students a considerable

variety of instructional support services. We often bemoan the fact that the students do not avail

themselves of these services. Perhaps this is because we do not draw their attention to the

possibilities. The library is probably the oldest resource, and perhaps still the richest. Include a brief

statement in the syllabus identifying collections, journals, abstracts, audio or video tapes, etc. which

the library has which are relevant to the course would be appropriate. If the institution has a

learning center, making the students aware of its services can be of real benefit to students. In

today's world computers are becoming almost a necessity. Most campuses have some terminals, if

not personal computers, available for student use. Many courses have other support services unique

to them. Briefly describe what is available in the syllabus, or tell the students where they can get

detailed information.

Beyond the Syllabus

While reading this paper it has undoubtedly occurred to many of you that our suggestions often are

based on certain assumptions about what is appropriate for a course of what constitutes effective

teaching. You are, of course, correct. "Before the Syllabus" would really be a better title for this

section. If one of the main purposes of a syllabus is to communicate to the students what the course

is about, it presumes that we have some idea about what we think the course should accomplish. It

requires that we have planned the course.

Other than commenting generally on the content of the course, most writers do not raise special

questions about the underpinnings of the course. Lowther's et al. (1989) Preparing Course Syllabi

for Improved Communication is a significant exception. They list educational beliefs as a separate

area, including beliefs about students, beliefs about educational purpose, and beliefs about the

teaching role. This concern will come as not surprise to those acquainted with the work of Stark,

Lowther, and their colleagues at NCRIPTAL studying course planning. In addition to the above

publication, the following are suggested for the reader who wishes to read on the topic in depth

(Peterson, Cameron, Mets, Jones & Ettington, 1986; Start & Lowther, 1986; Stark, Lowther,

Bentley, Ryan, Martens, Genthon, Wren, & Shaw, 1990; Stark, Lowther, Ryan, Bomotti, Genthon,

Haven, & Martens, 1988; Stark, Lowther, Ryan, and Genthon, 1988; Stark, Shaw, and Lowther,

1989).

For readers wishing a single book, Diamond's (1988) Designing and Improving Courses and

Curricula in Higher Education is a thorough one-volume treatment on course design. For

something even (79 pages), try Gronlund's (1985) Stating Objectives for Classroom Instruction. For

Вам также может понравиться

- What's in A Syllabus?Документ4 страницыWhat's in A Syllabus?Airine LerioОценок пока нет

- Subject of The Study Thesis MeaningДокумент6 страницSubject of The Study Thesis Meaningvictoriasotodenton100% (2)

- 2013 Pdac Jan 18Документ23 страницы2013 Pdac Jan 18Ibrahim QariОценок пока нет

- (Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics) Saari, Donald G. - Mathematics of Finance - An Intuitive Introduction-Springer (2019)Документ155 страниц(Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics) Saari, Donald G. - Mathematics of Finance - An Intuitive Introduction-Springer (2019)John Doe100% (1)

- Thesis Title For Mapeh MajorДокумент8 страницThesis Title For Mapeh MajorJessica Navarro100% (2)

- Thesis About Curriculum DevelopmentДокумент8 страницThesis About Curriculum DevelopmentPaperHelperSingapore100% (2)

- Example of Coursework EssayДокумент5 страницExample of Coursework Essayafiwhlkrm100% (2)

- Thesis TheoryДокумент4 страницыThesis TheoryPayToWriteAPaperMilwaukee100% (1)

- Law Dissertation Contents PageДокумент5 страницLaw Dissertation Contents PagePaperWritersCanada100% (1)

- How To Make A Background Study in ThesisДокумент6 страницHow To Make A Background Study in Thesispatriciaviljoenjackson100% (2)

- EDPM01 Proposal ProformaДокумент4 страницыEDPM01 Proposal ProformaSimon Kan0% (1)

- Teacher Education Research Paper TopicsДокумент5 страницTeacher Education Research Paper Topicsgipinin0jev2100% (1)

- Topics in Research Paper About EducationДокумент5 страницTopics in Research Paper About EducationmtxziixgfОценок пока нет

- Thesis Guidelines Chapter 1Документ5 страницThesis Guidelines Chapter 1Angelina Johnson100% (1)

- Lecture Method 1Документ6 страницLecture Method 1hariselvarajОценок пока нет

- Find The Thesis Statement ActivityДокумент6 страницFind The Thesis Statement ActivityTracy Morgan100% (2)

- Wharton Teaching Best Practice AY19 20 v1.3Документ13 страницWharton Teaching Best Practice AY19 20 v1.3Diego Benavente PatiñoОценок пока нет

- Sample Introduction For Thesis About EducationДокумент6 страницSample Introduction For Thesis About Educationtheresasinghseattle100% (2)

- Writing Background Information For Research PaperДокумент9 страницWriting Background Information For Research PaperafnjowzlseoabxОценок пока нет

- Thesis Topics For Special EducationДокумент5 страницThesis Topics For Special Educationfqzaoxjef100% (1)

- 3 Page Research Paper TopicsДокумент5 страниц3 Page Research Paper Topicsfvgymwfv100% (1)

- What Is Coursework in High SchoolДокумент6 страницWhat Is Coursework in High Schoollozuzimobow3100% (2)

- Term Paper Research TopicsДокумент8 страницTerm Paper Research Topicsaflsodqew100% (1)

- Uncovering Student Ideas in Science, Volume 1: 25 Formative Assessment ProbesОт EverandUncovering Student Ideas in Science, Volume 1: 25 Formative Assessment ProbesОценок пока нет

- Topic For Research Paper About EducationДокумент5 страницTopic For Research Paper About Educationeh15arsx100% (1)

- Performance-Based Assessment for 21st-Century SkillsОт EverandPerformance-Based Assessment for 21st-Century SkillsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (14)

- Thesis How To Make IntroductionДокумент5 страницThesis How To Make Introductionfipriwgig100% (1)

- Dissertation Importance of StudyДокумент5 страницDissertation Importance of StudyPaperWritersSingapore100% (1)

- Research Paper Reading StrategiesДокумент8 страницResearch Paper Reading Strategiesgz8aqe8w100% (1)

- Online Learning Support for Grade 12 StudentsДокумент7 страницOnline Learning Support for Grade 12 StudentsJoseph WalaanОценок пока нет

- Research Paper On Vocabulary DevelopmentДокумент6 страницResearch Paper On Vocabulary Developmentfvhk298x100% (1)

- Brunel Dissertation ResultsДокумент7 страницBrunel Dissertation ResultsWriteMyPaperForMeFastUK100% (2)

- Formative Evaluation As An Indicator of Student Wants and AttitudesДокумент8 страницFormative Evaluation As An Indicator of Student Wants and AttitudesTamarОценок пока нет

- Thesis Proposal Reading ComprehensionДокумент8 страницThesis Proposal Reading Comprehensionnicolewilliamslittlerock100% (2)

- Example Term Paper Topics High SchoolДокумент7 страницExample Term Paper Topics High Schoolea3vk50y100% (1)

- Syllabus Construction GuideДокумент5 страницSyllabus Construction GuideEfris FrisnandaОценок пока нет

- The Art of Case Analysis: How To Improve Your Classroom PerformanceОт EverandThe Art of Case Analysis: How To Improve Your Classroom PerformanceОценок пока нет

- Teaching Assistant ThesisДокумент7 страницTeaching Assistant Thesislelaretzlaffsiouxfalls100% (2)

- Coursework and DissertationДокумент5 страницCoursework and DissertationPaperWritingServicesLegitimateUK100% (1)

- High School Thesis Statement ExercisesДокумент8 страницHigh School Thesis Statement Exercisesafknkzkkb100% (2)

- Managing Complex Learning with STAR.Legacy SoftwareДокумент40 страницManaging Complex Learning with STAR.Legacy SoftwareViridiana González LópezОценок пока нет

- Masters Degree by Dissertation OnlyДокумент6 страницMasters Degree by Dissertation OnlyWriteMyPaperForMeFastNaperville100% (1)

- WWW - Economicsnetwork.ac - Uk Handbook Printable GtaДокумент23 страницыWWW - Economicsnetwork.ac - Uk Handbook Printable GtaSana BhittaniОценок пока нет

- Thesis Importance of The StudyДокумент6 страницThesis Importance of The Studyashleylovatoalbuquerque100% (2)

- Senior Thesis Research Paper TopicsДокумент8 страницSenior Thesis Research Paper Topicsgz7y9w0s100% (1)

- Thesis On TBLTДокумент5 страницThesis On TBLTnicolesavoielafayette100% (2)

- Beda Coursework and ResearchДокумент8 страницBeda Coursework and Researchafiwjkfpc100% (2)

- EDPM01 Blank Proposal Proforma (All Phases)Документ4 страницыEDPM01 Blank Proposal Proforma (All Phases)Simon KanОценок пока нет

- 47 Editable Syllabus Templates (Course Syllabus) TemplateLabДокумент57 страниц47 Editable Syllabus Templates (Course Syllabus) TemplateLabLee RudeenОценок пока нет

- Significance of The Study in Thesis Writing SampleДокумент4 страницыSignificance of The Study in Thesis Writing Samplebsr8frht100% (2)

- Research Paper Elementary StudentsДокумент5 страницResearch Paper Elementary Studentsaflbtvmfp100% (1)

- Research or CourseworkДокумент5 страницResearch or Courseworkhggrgljbf100% (2)

- Some High School Coursework MeaningДокумент6 страницSome High School Coursework Meaningfvntkabdf100% (2)

- Sample Thesis Chapter 1 Background of The StudyДокумент6 страницSample Thesis Chapter 1 Background of The Studyjenwilliamsneworleans100% (2)

- Thesis Making Significance of The StudyДокумент7 страницThesis Making Significance of The Studyk1lod0zolog3100% (1)

- Problem and Its Setting Thesis SampleДокумент6 страницProblem and Its Setting Thesis Samplesandragibsonnorman100% (2)

- Thesis Title Proposal For Special EducationДокумент5 страницThesis Title Proposal For Special Educationnibaditapalmerpaterson100% (2)

- Dissertation Proposal Early Childhood StudiesДокумент7 страницDissertation Proposal Early Childhood StudiesBuyPapersOnlineForCollegePaterson100% (1)

- Surgical Endoscopy Instructions For Authors Please NoteДокумент10 страницSurgical Endoscopy Instructions For Authors Please NoteimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- Michaels 2006Документ7 страницMichaels 2006imherestudyingОценок пока нет

- Standard Varicose Vein Surgery: J M T PerkinsДокумент8 страницStandard Varicose Vein Surgery: J M T PerkinsimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- Factors Influencing Quality of Life Following Lower Limb Amputation For Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureДокумент11 страницFactors Influencing Quality of Life Following Lower Limb Amputation For Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- Amputation and RehabilitationДокумент4 страницыAmputation and RehabilitationimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- S1 2014 284833 BibliographyДокумент6 страницS1 2014 284833 BibliographyPrama SistaОценок пока нет

- Checklist For Diagnostic Accuracy-StudiesДокумент3 страницыChecklist For Diagnostic Accuracy-StudiesConstanza PintoОценок пока нет

- D 14215Документ2 страницыD 14215imherestudyingОценок пока нет

- DafДокумент2 страницыDafimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- EДокумент34 страницыEimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- 7413 26793 1 PBДокумент4 страницы7413 26793 1 PBEvalia ArifinОценок пока нет

- 39.2 Laparoscopic Adrenalectomy: Ahmad Assalia, M.D. Michel Gagner, M.D., FACS, FRCSCДокумент13 страниц39.2 Laparoscopic Adrenalectomy: Ahmad Assalia, M.D. Michel Gagner, M.D., FACS, FRCSCimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- What are exceptions in PythonДокумент28 страницWhat are exceptions in PythonimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- GДокумент42 страницыGimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- Abc 2Документ53 страницыAbc 2paniceaОценок пока нет

- Itera&on: - Need One More Concept To Be Able To Write Programs of Arbitrary ComplexityДокумент33 страницыItera&on: - Need One More Concept To Be Able To Write Programs of Arbitrary ComplexitypaniceaОценок пока нет

- 2Документ1 страница2imherestudyingОценок пока нет

- BДокумент32 страницыBimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- Missing Link in Assessing and Improving Academic Achievement. ASHE-ERIC HigherДокумент1 страницаMissing Link in Assessing and Improving Academic Achievement. ASHE-ERIC HigherimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- 6.00 Introduc-On To Computer Science and ProgrammingДокумент20 страниц6.00 Introduc-On To Computer Science and ProgrammingJustin CollinsОценок пока нет

- ReferencesДокумент1 страницаReferencesimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- Writing A SyllabusДокумент1 страницаWriting A SyllabusimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- Course schedule and policiesДокумент1 страницаCourse schedule and policiesimherestudyingОценок пока нет

- Kent State University Master of Library and Information Science Project Learning OutcomesДокумент6 страницKent State University Master of Library and Information Science Project Learning Outcomesapi-436675561Оценок пока нет

- Conners 3 Parent Assessment ReportДокумент19 страницConners 3 Parent Assessment ReportSamridhi VermaОценок пока нет

- Derivatives of Complex Functions: Bernd SCHR OderДокумент106 страницDerivatives of Complex Functions: Bernd SCHR OderMuhammad Rehan QureshiОценок пока нет

- Exploratory Practice Rethinking Practitioner Research in Language Teaching 2003Документ30 страницExploratory Practice Rethinking Practitioner Research in Language Teaching 2003Yamith J. Fandiño100% (1)

- Cheyenne Miller: Cmill893@live - Kutztown.eduДокумент2 страницыCheyenne Miller: Cmill893@live - Kutztown.eduapi-509036585Оценок пока нет

- Writing ObjectivesДокумент32 страницыWriting ObjectivesTita RakhmitaОценок пока нет

- Post Lesson ReflectionДокумент8 страницPost Lesson Reflectionapi-430394514Оценок пока нет

- HRM Chap 6 Test Bank Questions PDFДокумент46 страницHRM Chap 6 Test Bank Questions PDFSanjna ChimnaniОценок пока нет

- DLL W3Документ6 страницDLL W3Jessa CanopinОценок пока нет

- Serve With A SmileДокумент49 страницServe With A Smilerajanarora72Оценок пока нет

- On Writing The Discussion...Документ14 страницOn Writing The Discussion...Rosalyn Gunobgunob-MirasolОценок пока нет

- DepEd UpdatedRPMSManualДокумент249 страницDepEd UpdatedRPMSManualJeffrey Farillas100% (3)

- Identifying and Selecting Curriculum MaterialsДокумент23 страницыIdentifying and Selecting Curriculum MaterialsCabral MarОценок пока нет

- Reaction Paper in Purposive CommunicationДокумент9 страницReaction Paper in Purposive CommunicationZera VermillionОценок пока нет

- Singapore MathДокумент116 страницSingapore Mathkarlamae657100% (16)

- Tierra Monique - Specialization 1 - RW2Документ8 страницTierra Monique - Specialization 1 - RW2Monique TierraОценок пока нет

- GS PricelistДокумент2 страницыGS PricelistKimberly OlaveОценок пока нет

- GTGC-RID-OP-FRM-24 Employee Annual EvaluationДокумент2 страницыGTGC-RID-OP-FRM-24 Employee Annual EvaluationDanny SolvanОценок пока нет

- Eapp Lesson 1Документ42 страницыEapp Lesson 1angelicaОценок пока нет

- Efforts and Difficulties in Teaching Vocabulary: N. V. F. Liando, J. D. Adam, T. K. LondaДокумент5 страницEfforts and Difficulties in Teaching Vocabulary: N. V. F. Liando, J. D. Adam, T. K. LondaChery BlossomОценок пока нет

- Uncertainty Environments and Game Theory SolutionsДокумент10 страницUncertainty Environments and Game Theory Solutionsjesica poloОценок пока нет

- CIE Biology International A-Level: Evaluation of Methods and DataДокумент3 страницыCIE Biology International A-Level: Evaluation of Methods and DataShania SmithОценок пока нет

- Chapter 8 - Learning To Communicate ProfessionallyДокумент4 страницыChapter 8 - Learning To Communicate ProfessionallyKTОценок пока нет

- First Reading Part 3Документ2 страницыFirst Reading Part 3Anonymous 0PRCsW60% (1)

- Test Bank For Social Psychology 5th Edition Tom GilovichДокумент13 страницTest Bank For Social Psychology 5th Edition Tom GilovichDevin MckayОценок пока нет

- Customizing Keynote to fit courses of 60, 90 or 120 hoursДокумент8 страницCustomizing Keynote to fit courses of 60, 90 or 120 hoursAmОценок пока нет

- Introduction to the Science of ErgonomicsДокумент19 страницIntroduction to the Science of ErgonomicsMJ Jhap FamadicoОценок пока нет

- The Reading The Mind in The Eyes TestДокумент13 страницThe Reading The Mind in The Eyes TestMonaОценок пока нет

- GTU Project Management CourseДокумент3 страницыGTU Project Management CourseAkashОценок пока нет

- Write To Heal WorkbookДокумент24 страницыWrite To Heal WorkbookKarla M. Febles BatistaОценок пока нет