Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Books Electronics Final

Загружено:

melissaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Books Electronics Final

Загружено:

melissaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

25 Books (electronics)

Title

Vocabulary and the simple

Content

One way of understanding the reading process and its

view of reading

components is the simple view model of reading (Gough Nelson, 2012)

comprehension

& Tunmer, 1986; Hoover &Gough, 1990). According to

the simple view, reading comprehension is the product of

decoding and language comprehension: R=DxLC. During

early reading development, reading comprehension

and listening or language comprehension (LC) are closely

correlated. As the words and structures in texts become

more complex, the child encounters words and syntax not

used in spoken language. In this simple view, as children

develop accurate and fluent decoding and word reading

skills in the early elementary grades, decoding has a

lesser influence on reading comprehension in the upper

elementary grades. At that point, language

comprehension including vocabulary knowledge plays a

greater role in reading comprehension.

Vocabulary knowledge and the network of word and

knowledge connections are, not surprisingly, the

strongest predictors of reading comprehension.

Childrens vocabulary knowledge at school entry predicts

word reading ability at the end of first grade (Senechal &

References

(Patricia F. Vadasy, J. Ron

25 Books (electronics)

Cornell, 1993). Vocabulary knowledge continues to

predict reading to predict reading comprehension up

through the 11th grade (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1998;

VOCABULARY

Muter, Hulme, Snowling, &Stevenson, 2004)

Vocabulary knowledge is fundamental to reading

INSTRUCTION AND

comprehension; one can't understand text without

READING

knowing what most of the words mean. A wealth of

COMPREHENSION

research has documented the strength of the relationship

between vocabulary and comprehension. The proportion

of difficult words in a text is the single most powerful

predictor of text difficulty, and a reader's general

vocabulary knowledge is the single best predictor of how

well that reader can understand text (Anderson &

Freebody, 1981). Increasing vocabulary knowledge is a

fundamental part of the process of education, both as a

means and as an end. Lack of adequate vocabulary

knowledge is already an obvious and serious obstacle for

many students, and the number of such students can be

expected to rise as an increasing proportion of our

students fall into categories considered educationally at

risk. At the same time, advances in knowledge will create

an ever-larger pool of concepts and words that a person

(Nagy, 1998)

25 Books (electronics)

must master to be literate and employable. The

obviousness of the need and the strong relationship

between vocabulary and comprehension invite an overly

simplistic response: if we simply teach students more

words, they will understand text better. However, not all

vocabulary instruction increases reading comprehension.

In fact, according to several studies, many widely used

methods of vocabulary instruction generally fail to

increase reading comprehension (Mezynski, 1983;

Pearson & Gallagher, 1983; Stahl & Fairbanks, 1986). Let

me present the point in another way. Imagine an

experiment with two groups of students about to read a

selection from a textbook. One group is given typical

instruction on the meanings of some difficult words from

that selection; the other group doesn't receive any

instruction. Then both groups are given the passage to

read, and tested for comprehension. Do the students who

received the vocabulary instruction do any better on the

comprehension test? Very often, they don't. This news (if

it is news) should be unsettling. A major motivation for

vocabulary instruction is to help students understand

material they are about to read. If traditional instruction is

25 Books (electronics)

not having this effect, teachers should know why not, and

what to do about it. The purpose of this report, then, is to

lay out, on the basis of the best available research, how

one can use vocabulary instruction most effectively to

improve reading comprehension. The term "vocabulary"

will be used primarily for reading vocabulary; it should

therefore be noted that the discussion will be relevant

primarily to students already past the initial stages of

reading, for whom learning new words means acquiring

new meanings, and not just learning to recognize in print

words already a part of their oral vocabulary. Although the

focus is on improving reading comprehension, some

connections will be made to other aspects of instruction,

linking vocabulary instruction and reading comprehension

with broader goals of the language arts program.

Examples of useful approaches to vocabulary

instruction--mainly, but not exclusively prereading

activities--will be presented for use or adaptation by

classroom teachers. The primary purpose, however, is

not to provide a smorgasbord of activities, but to provide

the teacher with a knowledge of how and why one can

choose and adapt vocabulary-related activities to

25 Books (electronics)

Vocabulary Knowledge and

maximize their effectiveness.

The relationship between vocabulary knowledge and

(Marcella Hu Hsueh-chao, Paul

Comprehension

reading comprehension is complex and dynamic. One

Nation, 2000)

way of looking at it is to divide it up into two major

directions of effect- the effect of vocabulary knowledge on

reading comprehension (which is the main focus of this

paper) and the effect of reading comprehension on

vocabulary knowledge or growth.

Chall (1987) suggests that these two effects achieve

prominence at different times for young native speakers

of English. When they begin to learn how to read, native

speakers vocabulary knowledge supports their reading

comprehension. That is, typically they work with texts that

contain only known vocabulary. As native speakers begin

school with a vocabulary approaching 5,000 word families

this is not difficult to arrange. After three or four years of

learning to read, the relationship changes. Having gained

control of many of the skills of reading, reading can

become a means of vocabulary growth. That is, the

learner learns new vocabulary through reading words that

have not been met elsewhere.

Researchers have suggested several models to describe

25 Books (electronics)

the relationship between vocabulary knowledge and

reading comprehension. The factors involved in these

models involve language knowledge (of which vocabulary

knowledge is a part),knowledge of the world (sometimes

called background knowledge) and skill in language use

(of which reading comprehension is one result).

A large number of different types of studies have shown

the strong statistical relationship between vocabulary and

language use. The causal relationships, however, are not

so clear. Anderson and Freebody (1981) and Nation

(1993) distinguish three views that are reflected in

Shared Reading to Build

research.

Numerous scholars have discussed the value of shared

Vocabulary and

reading for childrens vocabulary acquisition and the link

Comprehension

between vocabulary knowledge and overall

comprehension (Coyne, Simmons. Kameenui, &

Stoolmiller, 2004; Fisher, Frey &Lapp, 2008; McKeown &

Beck, 2006). Fisher et al. (2008) identified four areas of

instruction that teachers with expertise in shared reading

in grades 3 through 8 demonstrated: comprehension,

vocabulary, text structures and text features.

McKeown and Beck (2006) explained that young children,

(Kesler, 2010)

25 Books (electronics)

especially those from nondominant groups, need explicit

support with comprehending the decontextualized

language in books, which, they contended, is a major

source of learning and thus is at the center of academic

achievement (p. 293). To do this, teachers need to

support expansive, thoughtful responses, aiming to get

children to explain, elaborate and connect their ideas

(p.293) and produce language.

Вам также может понравиться

- Examining The Effects of Explicit Teaching of Context Clues in Content Area TextsДокумент6 страницExamining The Effects of Explicit Teaching of Context Clues in Content Area TextsNI KOОценок пока нет

- Stem Whitepaper Developing Academic VocabДокумент8 страницStem Whitepaper Developing Academic VocabKainat BatoolОценок пока нет

- Statement of ProblemДокумент4 страницыStatement of ProblemMohd AizatОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1Документ11 страницChapter 1DENMARK100% (1)

- TEL - Volume 5 - Issue 1 - Pages 45-71Документ27 страницTEL - Volume 5 - Issue 1 - Pages 45-71ENSОценок пока нет

- So Tay Tu Vung Hoc Thuat 01-09Документ83 страницыSo Tay Tu Vung Hoc Thuat 01-09Dao Anh HienОценок пока нет

- The Relationship Between Text Comprehension and Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition: Word-Focused TasksДокумент15 страницThe Relationship Between Text Comprehension and Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition: Word-Focused TasksNurОценок пока нет

- Schema and Reading Comprehension Relative To Academic Performance of Grade 10 Students at Binulasan Integrated SchoolДокумент12 страницSchema and Reading Comprehension Relative To Academic Performance of Grade 10 Students at Binulasan Integrated SchoolShenly EchemaneОценок пока нет

- Vocab and Learning CycleДокумент15 страницVocab and Learning Cyclebsimmons1989Оценок пока нет

- Sbrady Edrd 830 Final PaperДокумент25 страницSbrady Edrd 830 Final Paperapi-456699912Оценок пока нет

- Feasibility Study. CastilloДокумент16 страницFeasibility Study. CastilloEunice GabrielОценок пока нет

- Annotated BibДокумент15 страницAnnotated Bibapi-621535429Оценок пока нет

- Vocabulary Development: Understanding What One ReadsДокумент11 страницVocabulary Development: Understanding What One ReadsDanica Jean AbellarОценок пока нет

- Thesis Chapter 1Документ21 страницаThesis Chapter 1Bea DeLuis de TomasОценок пока нет

- RES1 - SuliaManlangitPongase - Chapters123 UPDATED April 20Документ50 страницRES1 - SuliaManlangitPongase - Chapters123 UPDATED April 20Regine MalanaОценок пока нет

- Teaching VocabularyДокумент8 страницTeaching VocabularyDesu AdnyaОценок пока нет

- Project SPRSDДокумент25 страницProject SPRSDAnaisa MirandaОценок пока нет

- Reference - A Focus On VocabularyДокумент32 страницыReference - A Focus On VocabularyTri NguyenОценок пока нет

- Lit Review PaperДокумент7 страницLit Review PaperNicole SelhorstОценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Vocabulary Know E8f5e72aДокумент13 страницRelationship Between Vocabulary Know E8f5e72aLinda Himnida0% (1)

- Pellicer Sanchez - Lang.12430Документ42 страницыPellicer Sanchez - Lang.12430tux52003Оценок пока нет

- Orthographic Facilitation of First Graders VocabuДокумент21 страницаOrthographic Facilitation of First Graders VocabuLic. GIULIANA BEATRIZ POLO VALDIVIESOОценок пока нет

- Classroom Vocabulary AssessmentДокумент15 страницClassroom Vocabulary AssessmentgeronimlОценок пока нет

- Calub ARДокумент30 страницCalub ARMarvin Yebes ArceОценок пока нет

- Vocabulary Acquisition Paul Nation 1989Документ139 страницVocabulary Acquisition Paul Nation 1989juanhernandezloaizaОценок пока нет

- Johnson Mandi MPДокумент22 страницыJohnson Mandi MPRyann LeynesОценок пока нет

- Contoh Esai SLAДокумент3 страницыContoh Esai SLAagwindrwОценок пока нет

- Reading in Esl AnsДокумент15 страницReading in Esl AnsKANISKA A/P MAYALAGAN STUDENTОценок пока нет

- Background of The StudyДокумент30 страницBackground of The StudyMarvin Yebes ArceОценок пока нет

- Cognitive ReadingДокумент16 страницCognitive ReadingSiti Meisaroh100% (1)

- Reading Comprehension Research Paper2Документ22 страницыReading Comprehension Research Paper2dewiОценок пока нет

- Annotated Portfoliocopysped637 Annot BibДокумент8 страницAnnotated Portfoliocopysped637 Annot Bibapi-348149030Оценок пока нет

- PART 3 - TOPIC 3 Concepts, Theories and Principles of Vocabulary and Reading ComprehensionДокумент13 страницPART 3 - TOPIC 3 Concepts, Theories and Principles of Vocabulary and Reading ComprehensionApenton MimiОценок пока нет

- Stahl Voc Assess RTДокумент13 страницStahl Voc Assess RTDr-Mushtaq AhmadОценок пока нет

- A Review of Research Into Vocabulary Learning and AcquisitionДокумент9 страницA Review of Research Into Vocabulary Learning and Acquisitionman_dainese100% (1)

- The Modern Language Journal - 2020 - JIN - Incidental Vocabulary Learning Through Listening To Teacher TalkДокумент17 страницThe Modern Language Journal - 2020 - JIN - Incidental Vocabulary Learning Through Listening To Teacher Talk123123123abcdefghОценок пока нет

- God Is The AnswerДокумент76 страницGod Is The AnswerYona AranteОценок пока нет

- ChouДокумент8 страницChouyounghorseОценок пока нет

- Close Reading As An Intervention For Struggling Middle School ReadersДокумент12 страницClose Reading As An Intervention For Struggling Middle School ReadersNurilMardatilaОценок пока нет

- 1 StylisticsДокумент15 страниц1 StylisticsYohana ZiraОценок пока нет

- Literature Review - Zhe YangДокумент7 страницLiterature Review - Zhe Yangapi-457181569Оценок пока нет

- 2003 ThesisДокумент23 страницы2003 ThesisMaria Lucille Mejias IIОценок пока нет

- A Focus On VocabularyДокумент24 страницыA Focus On VocabularyLuizArthurAlmeidaОценок пока нет

- Teaching Vocabulary: Components of Vocabulary InstructionДокумент7 страницTeaching Vocabulary: Components of Vocabulary Instructionhima67100% (1)

- A Systematic ReviewДокумент24 страницыA Systematic ReviewChris KotchieОценок пока нет

- Scaffolding - in ListeningДокумент7 страницScaffolding - in Listeningeqb007Оценок пока нет

- A Review On Reading Theories and Its Implication To TheДокумент10 страницA Review On Reading Theories and Its Implication To TheMarcio NoeОценок пока нет

- Child Development - 2017 - Lerv G - Unpicking The Developmental Relationship Between Oral Language Skills and ReadingДокумент18 страницChild Development - 2017 - Lerv G - Unpicking The Developmental Relationship Between Oral Language Skills and Readingpablozz1Оценок пока нет

- The Effects of The 3-2-1 Reading Strategy On EFL Reading ComprehensionДокумент8 страницThe Effects of The 3-2-1 Reading Strategy On EFL Reading Comprehensionnghiemthuy92Оценок пока нет

- C S M R C P S S S P, S K V A PДокумент26 страницC S M R C P S S S P, S K V A PrfernzОценок пока нет

- Lerv-G Et Al-2017-Child DevelopmentДокумент19 страницLerv-G Et Al-2017-Child DevelopmentAcintiaОценок пока нет

- Tract 7Документ61 страницаTract 7Renaldi SamloyОценок пока нет

- Whole To PartДокумент5 страницWhole To PartRebecca ThomasОценок пока нет

- Middle School Vocabulary Strategies - InfoДокумент11 страницMiddle School Vocabulary Strategies - InfoCamelia FrunzăОценок пока нет

- PRE-TEST (World Religion)Документ3 страницыPRE-TEST (World Religion)Marc Sealtiel ZunigaОценок пока нет

- Anna May de Leon Galono, A089 528 341 (BIA Sept. 29, 2015)Документ7 страницAnna May de Leon Galono, A089 528 341 (BIA Sept. 29, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCОценок пока нет

- Creed Article 4 PPSXДокумент17 страницCreed Article 4 PPSXOremor RemerbОценок пока нет

- The Wilderness - Chennai TimesДокумент1 страницаThe Wilderness - Chennai TimesNaveenОценок пока нет

- Creative WritingДокумент13 страницCreative WritingBeberly Kim AmaroОценок пока нет

- George Herbert Scherff Walker Bush: Agentur of The New World OrderДокумент36 страницGeorge Herbert Scherff Walker Bush: Agentur of The New World Orderextemporaneous100% (3)

- Charging Station Location and Sizing For Electric Vehicles Under CongestionДокумент20 страницCharging Station Location and Sizing For Electric Vehicles Under CongestionJianli ShiОценок пока нет

- Mca Lawsuit Details English From 2007 To Feb 2021Документ2 страницыMca Lawsuit Details English From 2007 To Feb 2021api-463871923Оценок пока нет

- CJ1W-PRT21 PROFIBUS-DP Slave Unit: Operation ManualДокумент100 страницCJ1W-PRT21 PROFIBUS-DP Slave Unit: Operation ManualSergio Eu CaОценок пока нет

- Pineapple Working PaperДокумент57 страницPineapple Working PaperAnonymous EAineTiz100% (7)

- 5130 - 05 5G Industrial Applications and SolutionsДокумент113 страниц5130 - 05 5G Industrial Applications and SolutionsMauricio SantosОценок пока нет

- PSCI101 - Prelims ReviewerДокумент3 страницыPSCI101 - Prelims RevieweremmanuelcambaОценок пока нет

- CIR vs. Estate of Benigno P. Toda, JRДокумент13 страницCIR vs. Estate of Benigno P. Toda, JRMrln VloriaОценок пока нет

- Beacon Explorer B Press KitДокумент36 страницBeacon Explorer B Press KitBob AndrepontОценок пока нет

- Akshaya Tritya! One of The Ancient Festivals of IndiaДокумент9 страницAkshaya Tritya! One of The Ancient Festivals of IndiaHoracio TackanooОценок пока нет

- Tyvak PlatformsДокумент1 страницаTyvak PlatformsNguyenОценок пока нет

- IX Paper 2Документ19 страницIX Paper 2shradhasharma2101Оценок пока нет

- Piggery BookletДокумент30 страницPiggery BookletVeli Ngwenya100% (2)

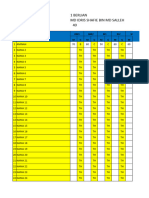

- TEMPLATE Keputusan Peperiksaan THP 1Документ49 страницTEMPLATE Keputusan Peperiksaan THP 1SABERI BIN BANDU KPM-GuruОценок пока нет

- (I) (Ii) (Iii) (Iv) : Nahata Professional Academy Q1. Choose The Correct AnswerДокумент5 страниц(I) (Ii) (Iii) (Iv) : Nahata Professional Academy Q1. Choose The Correct AnswerBurhanuddin BohraОценок пока нет

- NYC Ll11 Cycle 9 FinalДокумент2 страницыNYC Ll11 Cycle 9 FinalKevin ParkerОценок пока нет

- QuizДокумент15 страницQuizGracie ChongОценок пока нет

- 7999 Cswdo Day CareДокумент3 страницы7999 Cswdo Day CareCharles D. FloresОценок пока нет

- Marketing Communication I Assignment (Advertisement)Документ13 страницMarketing Communication I Assignment (Advertisement)Serene_98Оценок пока нет

- AIPT 2021 GuidelineДокумент4 страницыAIPT 2021 GuidelineThsavi WijayasingheОценок пока нет

- CVT / TCM Calibration Data "Write" Procedure: Applied VehiclesДокумент20 страницCVT / TCM Calibration Data "Write" Procedure: Applied VehiclesАндрей ЛозовойОценок пока нет

- Speakers Reaction PaperДокумент2 страницыSpeakers Reaction Papermaui100% (2)

- Aldehydes and Ketones LectureДокумент21 страницаAldehydes and Ketones LectureEvelyn MushangweОценок пока нет

- Welcome To UnixДокумент14 страницWelcome To UnixSrinivas KankanampatiОценок пока нет

- Xeljanz Initiation ChecklistДокумент8 страницXeljanz Initiation ChecklistRawan ZayedОценок пока нет