Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

What Is Political Economy Review

Загружено:

Bach AchacosoОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

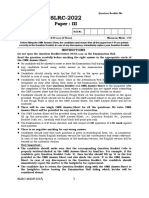

What Is Political Economy Review

Загружено:

Bach AchacosoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Royal African Society

Review

Author(s): Paul Nugent

Review by: Paul Nugent

Source: African Affairs, Vol. 85, No. 338 (Jan., 1986), pp. 147-148

Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of Royal African Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/722233

Accessed: 23-01-2016 04:38 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Royal African Society and Oxford University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

African Affairs.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 04:38:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BOOK REVIEWS

147

Significantly,when Wheatcroftfindshimselfon thin ice, he skatesfast andwrites

statementsthat, for example,Africanresentmentat their positionin contemporary

South Africa is really rather '. . . ambiguous. They want to be rid of white

supremacyand yet they want to go on enjoyingthe benefits of a rich industrial

society. Soweto is not merely a grim compound: it is the most prosperous

blackAfricancity anywhere. This explainsthe continuingfailureof the African

Nationalist [sic] Congress. . to stir up the blacks' (p. 268). Not only is

the thought of Soweto as 'prosperous' indefensible nonsense, present-day

developmentsin South Africagive the resoundinglie to Wheatcroft'sviews on the

ANC.

Instituteof Commonzvealth

Studies,

London

JEAN

JACQUES

VANHELTEN

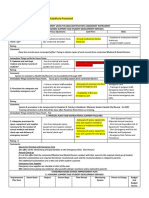

What Is Political Economy? A Study of Social Theory and

Underdevelopment, by Martin Staniland. Yale UniversityPress, New Haven

and London, 1985. xi + 229 pp. ISBN 0-300-03295-1. ,618 50 in UK.

As Stanilandbegins by noting, almost every other book these days carriesthe

term 'politicaleconomy'in the title or sub-title. Often nothing specificis meant

by this, but usually it is intended to convey the idea that the book in question

hopes to show in some way an interplaybetweeneconomicand politicalprocesses.

Stanilandarguesthat, in spite of sometimesbeing accordedthe statusof a theory,

politicaleconomyis reallyonly a broadfield in which opposingtheoreticalschools

compete. WhatIs PoliticalEconomy?,

then, is an explorationof how some of these

quite differentschools cope with the same problemof depicting the relationship

between economics and politics, ranging from theories that are deterministicto

those that are interactive. It covers neo-classicaleconomicsand the attemptsto

apply its assumptions to political behaviour; counter-theory reasserting the

primacy of politics; theories of internationalpolitical economy; and Marxism.

This considerationtogetherof theoriesthatareoften so at odds as regardsconcepts,

methodologyand valuesas to miss any point of contact,is largelywhat makesthis

bookso appealing. Inevitablyin a bookwith this breadthof focus, whatthe author

says about the content of the theoriesis fairly schematicand some of the critiques

aresecond-hand,but the resultis as lucid andaccurateas one couldhope for.

A dominanttheme of the book is the quite differentexpectationsand development of theory in Western centres of learning and the Third World. In the

developed countries, Stanilandargues, theoreticaldebate has tended to produce

more complex interactive theories. Thus, neo-classical economics has been

criticizedon the grounds that the Adam Smithian stress on the primacyof the

individualand the marketbearslittle relevancein the modernworld of largecorporationsandincreasingstateinterventionism,but criticshavemerelyattemptedto

incorporatepower relationships none has apparentlygone so far as to write a

theory of political determinism. Theories that evolve in a Third World context,

by contrast,tend towardsa greaterdegree of determinism,as manifestedin the

growth of dependencytheory. Stanilanddoes not really attemptto explain why

this shouldbe so, althoughpresumablythe idea is that Third Worldacademicsare

on the whole as much concerned to change the world as to describe it. The

divergentdemandsof Third World theory resurfacein Staniland'sdiscussionof

Marxism. WithinWesternMarxism,dissatisfactionwith the instrumentalistview

of politicsin the classicaltraditionhas led to an assertionof the relativeautonomyof

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 04:38:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

148

AFRICANAFFAIRS

the state and a more complex accountof economic and politicalprocesses. But

within a Third World context, the further issue of the relationshipbetween

domesticand externalforces is raised. While some have adheredto the logic of

orthodoxMarxismand have portrayeddomesticpoliticalforcesas merelya reflection of the demandsof internationalcapital,Third World intellectualshave often

soughta theorythat gives some role to domesticclasses. The result,accordingto

Staniland,is that works such as that of Shivji are often an inversionof Marxist

analysis,vergingon politicism.

All of this gives plenty of food for thought,but one feels slightly cheatedby the

conclusionto the book. Having led his readerson a great trek through theory,

Stanilandleavesthemwith the followingproposition:as long as thereis a varietyof

cultures,therewill be a varietyof theories,and becausethese will containa variety

of valuesand assumptions,one can criticizethe theoriesbut never choosebetween

them. The readermight be excusedfor wonderinghow culturalvarietyhas stolen

centre-stagewhen, if anything,the book shows the strongestcorrelationbetween

theory and levels of development,which cuts across culture. Similarly,a new

book by Blomstromand Hettne (DevelopmentTheoryin Transition)shows how

qulte slmllarviews on dependencyhave emergedacrossthe Third World, sometimes independently. Secondly, it is difficultto see why underlyingvalues and

assumptionsshouldinsulatetheory. Marxismhas a strongvalue content,but the

validityof its analysis(and its values) can surely be assessed in the light of how

successfullyit copes with reality. It is true of course that no single theory has

managedto do justiceto all the complexitiesof humansociety but this is another

argument, besides which there is a clear distinction between theory that is

inherentlylimited (one thinks of 'public choice') and theory that possesses the

concepts but has not masteredthe equation. In spite of this, What Is Political

Ecorlomy?

will be of interestto a wide audience,not leastto Africanistswho will find

manyfamiliardebatesset in the contextof the problematicof the book.

Schoolof OrientalandAfricanStudies,

London

PAUL

NUGENT

.

And Night Fell, by Molefe Pheto. London, Allison and Busby, 1983. 218

PP

?8 95

It says somethingfor the impactthat this book has had that it has alreadybeen

snappedup as a paperbaekby the HeinemannAfricanWriters Series (No. 258,

1985)withintwo yearsof its originalpublieation. This will no doubtgive it wider

eireulationbut the originalLondon publishers,Allison and Busby, are to be eongratulatedfor reeognizingdistinetionin what could easily have been a predietable

catalogueof poliee brutality. Just as too many images of starvingchildren or

urbanviolenceean numb the averagetelevisionviewer'ssensibilityso, regrettably

but it wouldbe wrongnot to admitit, thepraeticedreaderof SouthAfricanliterature

and watcherof South Afrieanplays can be over-exposedto the chillinglyeandid

prisoneell interrogationor the screamof agonyas the eleetrodesare appliedto the

testicles. These are ignoblereflectionsbut I believethem to be true. We can all

build up a resistanceto humansuffering.

It is thereforewith a sense of debt to Molefe Pheto that I reviewAndNight Fell,

for he re-awakensin me, and I am surein all his readers,a senseof immediacyat the

horrorof South Africa'sofficialrepression. His book is sub-titled'Memoirsof a

PoliticalPrisonerin South Africa'. It is a recordof 281 days spent in detention

This content downloaded from 103.231.241.233 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 04:38:21 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Вам также может понравиться

- Gazette August 6th 2021 Part A and DIRECTIVE (1549)Документ13 страницGazette August 6th 2021 Part A and DIRECTIVE (1549)Bach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Russ Kicks EVERYTHING YOU KNOW ABOUT GOD IS WRONG PDFДокумент54 страницыRuss Kicks EVERYTHING YOU KNOW ABOUT GOD IS WRONG PDFBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Limits of NeoliberalismДокумент185 страницLimits of NeoliberalismBach Achacoso100% (4)

- The Gnosis of Kali Yuga - Being A Summary of The Universal Science For The Awakening of ConsciousnessДокумент364 страницыThe Gnosis of Kali Yuga - Being A Summary of The Universal Science For The Awakening of ConsciousnessSulakshana Pandita100% (1)

- Roles For Theory in Contemporary Evaluation Practice: Developing Practical KnowledgeДокумент20 страницRoles For Theory in Contemporary Evaluation Practice: Developing Practical KnowledgeBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- 2018-12-01 Chad To Combat Boko Haram Closer To Nigerian Border (Zenn)Документ1 страница2018-12-01 Chad To Combat Boko Haram Closer To Nigerian Border (Zenn)Bach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- The Public Domain, Enclosing The Commons of The MindДокумент333 страницыThe Public Domain, Enclosing The Commons of The MindOscar EspinozaОценок пока нет

- Researchability: Why QuestionsДокумент5 страницResearchability: Why QuestionsBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Comparative Political EconomyДокумент28 страницComparative Political EconomyBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Clash of GlobalisationsДокумент336 страницClash of GlobalisationsAnamariaCioanca100% (5)

- Caroline Kippler Summer 10 Exploring Post DevelopmentДокумент38 страницCaroline Kippler Summer 10 Exploring Post Developmentkunal khadeОценок пока нет

- Inequality Democracy and InstitutionsДокумент13 страницInequality Democracy and InstitutionsBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Martinussen - Chapter 5Документ8 страницMartinussen - Chapter 5Bach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Globalization GlossaryДокумент3 страницыGlobalization GlossaryBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- SAPS in GhanaДокумент13 страницSAPS in GhanaBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Globalization GlossaryДокумент3 страницыGlobalization GlossaryBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- GlobalizationДокумент274 страницыGlobalizationBach Achacoso100% (1)

- Green EnvironmentДокумент10 страницGreen EnvironmentBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- The Causes of GlobalizationДокумент51 страницаThe Causes of GlobalizationBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- How To Judge GlobalismДокумент13 страницHow To Judge GlobalismBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- How To Judge GlobalismДокумент13 страницHow To Judge GlobalismBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- How To Write A Literature ReviewДокумент6 страницHow To Write A Literature ReviewBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Martinussen - Chapter 5Документ8 страницMartinussen - Chapter 5Bach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Using Programme TheoryДокумент20 страницUsing Programme TheoryBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Theory of ChangeДокумент16 страницTheory of ChangeBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Theory of ChangeДокумент16 страницTheory of ChangeBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Usaid Program Theory EvaluationДокумент88 страницUsaid Program Theory EvaluationBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- Debt For NatureДокумент98 страницDebt For NatureBach AchacosoОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- SLRC InstPage Paper IIIДокумент5 страницSLRC InstPage Paper IIIgoviОценок пока нет

- Bhuri Nath v. State of J&K (1997) 2 SCC 745Документ30 страницBhuri Nath v. State of J&K (1997) 2 SCC 745atuldubeyОценок пока нет

- International Scientific Journal "Interpretation and Researches"Документ5 страницInternational Scientific Journal "Interpretation and Researches"wowedi333Оценок пока нет

- Fill in The Blanks, True & False MCQs (Accounting Manuals)Документ13 страницFill in The Blanks, True & False MCQs (Accounting Manuals)Ratnesh RajanyaОценок пока нет

- Moodys SC - Russian Banks M&AДокумент12 страницMoodys SC - Russian Banks M&AKsenia TerebkovaОценок пока нет

- What Is GlobalizationДокумент19 страницWhat Is GlobalizationGiovanni Pierro C Malitao JrОценок пока нет

- Standard Oil Co. of New York vs. Lopez CasteloДокумент1 страницаStandard Oil Co. of New York vs. Lopez CasteloRic Sayson100% (1)

- Inbound Email Configuration For Offline ApprovalsДокумент10 страницInbound Email Configuration For Offline Approvalssarin.kane8423100% (1)

- TWG 2019 Inception Reports forERG 20190717 PDFДокумент95 страницTWG 2019 Inception Reports forERG 20190717 PDFGuillaume GuyОценок пока нет

- CM - Mapeh 8 MusicДокумент5 страницCM - Mapeh 8 MusicAmirah HannahОценок пока нет

- The City Bride (1696) or The Merry Cuckold by Harris, JosephДокумент66 страницThe City Bride (1696) or The Merry Cuckold by Harris, JosephGutenberg.org100% (2)

- Processes of Word Formation - 4Документ18 страницProcesses of Word Formation - 4Sarah Shahnaz IlmaОценок пока нет

- Color Code Look For Complied With ECE Look For With Partial Compliance, ECE Substitute Presented Look For Not CompliedДокумент2 страницыColor Code Look For Complied With ECE Look For With Partial Compliance, ECE Substitute Presented Look For Not CompliedMelanie Nina ClareteОценок пока нет

- Obaid Saeedi Oman Technology TransfeДокумент9 страницObaid Saeedi Oman Technology TransfeYahya RowniОценок пока нет

- Math 12 BESR ABM Q2-Week 6Документ13 страницMath 12 BESR ABM Q2-Week 6Victoria Quebral Carumba100% (2)

- Apple Case ReportДокумент2 страницыApple Case ReportAwa SannoОценок пока нет

- Undiscovered Places in MaharashtraДокумент1 страницаUndiscovered Places in MaharashtraNikita mishraОценок пока нет

- Group Floggers Outside The Flogger Abasto ShoppingДокумент2 страницыGroup Floggers Outside The Flogger Abasto Shoppingarjona1009Оценок пока нет

- Cosmetics & Toiletries Market Overviews 2015Документ108 страницCosmetics & Toiletries Market Overviews 2015babidqn100% (1)

- Name Position Time of ArrivalДокумент5 страницName Position Time of ArrivalRoseanne MateoОценок пока нет

- Analysis Essay of CPSДокумент6 страницAnalysis Essay of CPSJessica NicholsonОценок пока нет

- Grupo NovEnergia, El Referente Internacional de Energía Renovable Dirigido Por Albert Mitjà Sarvisé - Dec2012Документ23 страницыGrupo NovEnergia, El Referente Internacional de Energía Renovable Dirigido Por Albert Mitjà Sarvisé - Dec2012IsabelОценок пока нет

- ACCT 403 Cost AccountingДокумент7 страницACCT 403 Cost AccountingMary AmoОценок пока нет

- Intertek India Private LimitedДокумент8 страницIntertek India Private LimitedAjay RottiОценок пока нет

- Complete ES1 2023 Vol1Документ334 страницыComplete ES1 2023 Vol1Chandu SeekalaОценок пока нет

- Animal AkanДокумент96 страницAnimal AkanSah Ara SAnkh Sanu-tОценок пока нет

- Management Decision Case: Restoration HardwaДокумент3 страницыManagement Decision Case: Restoration HardwaRishha Devi Ravindran100% (5)

- PolinationДокумент22 страницыPolinationBala SivaОценок пока нет

- 雅思口语常用高效表达句型 PDFДокумент3 страницы雅思口语常用高效表达句型 PDFJing AnneОценок пока нет

- BrochureДокумент10 страницBrochureSaurabh SahaiОценок пока нет