Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

RAD

Загружено:

Andreea NicolaeАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

RAD

Загружено:

Andreea NicolaeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Attachment & Human Development,

March 2006; 8(1): 63 86

Reactive attachment disorder in maltreated twins

follow-up: From 18 months to 8 years

SHERRYL SCOTT HELLER1, NEIL W. BORIS1,2,

SARAH-HINSHAW FUSELIER3, TIMOTHY PAGE4,

NINA KOREN-KARIE5, & DEVI MIRON6

1

Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2Tulane University School of

Public Health & Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA, 3University of Texas at Austin, USA,

4

Louisiana State University, USA, 5University of Haifa, Israel, and 6Tulane University, New Orleans,

LA, USA

Abstract

The best means for the diagnosis and treatment of reactive attachment disorder of infancy and early

childhood have not been established. Though some longitudinal data on institutionalized children is

available, reports of maltreated young children who are followed over time and assessed with measures

of attachment are lacking. This paper presents the clinical course of a set of maltreated fraternal twins

who were assessed and treated from 19 months to 30 months of age and then seen in follow-up at 3 and

8 years of age. A summary of the early assessment and course is provided and findings from follow-up

assessments of the cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal functioning of each child is analysed.

Follow-up measures, chosen to capture social-cognitive processing of these children from an

attachment perspective, are highlighted. Finally, findings from the case are discussed from nosological

and theoretical perspectives.

Keywords: Maltreatment, attachment, reactive attachment disorder, case study, child abuse, adoption

Introduction

Appropriate assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of reactive attachment disorder (RAD)

have recently been debated in the literature (Zeanah & Boris, 2000; Zeanah & OConnor,

2003). Recent special issues of Attachment & Human Development (2003) and the Infant

Mental Health Journal (2004) have focused on the clinical and diagnostic controversies of

research on attachment disorders. One unresolved issue concerns the developmental course

of young children diagnosed with RAD. Though recent longitudinal data on children raised

in institutions are informative, there are no case studies in the peer-reviewed literature that

have followed maltreated children, raised in families and diagnosed in early childhood with

RAD. In this paper, an update of a case report first published in 1999 is presented

(Hinshaw-Fuselier, Boris, & Zeanah, 1999). The focus of this case report is on the cognitive,

socio-emotional, and behavioral development of fraternal twin siblings who were victims of

maltreatment and were placed in foster care before age 2 years. This paper begins with an

overview of the existing diagnostic nosology and controversies about its application in

Correspondence: Sherryl Scott Heller, PhD, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, USA.

E-mail: drsherrylheller@yahoo.com

ISSN 1461-6734 print/ISSN 1469-2988 online 2006 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/14616730600585177

64

S. S. Heller et al.

middle childhood. Included in this section is a review of available data on institutionalized

children and how this data may or may not inform our understanding of maltreated but not

institutionalized children. The case report follows beginning with a review of the childrens

history, their initial assessment, and the treatment course when they were aged 19

30 months (more details of the twins early history are available in the previous manuscript;

Hinshaw-Fuselier et al., 1999). A summary of an interim assessment when they were age 3

years precedes a more detailed description of newly standardized measures administered to

the children at 8 years of age. The findings from these measures, coded by research scientists

unaware of details of these childrens clinical history, rounds out the case material. The

paper concludes with a discussion of the twins symptoms from both a diagnostic and social

information processing perspective.

The diagnosis of reactive attachment disorder

Both DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and ICD-10 (World Health

Organization, 1992) require that the onset of RAD occur before the age of 5 years. In DSMIV, it is specified that pathogenic care precede the onset of symptoms. Both nosologies

also describe two types of RAD, inhibited and disinhibited. The major feature of the

inhibited subtype of RAD involves the child either failing to approach the caregiver or

approaching the caregiver in an abnormal manner (e.g., fearful approach) when clearly

distressed. Children diagnosed as RAD-inhibited also exhibit difficulties in emotional

regulation and a lack of social reciprocity. The disinhibited attachment pattern involves the

child approaching unfamiliar adults or exhibiting a lack of wariness of strangers. These

children may willingly wander off with a stranger, or seek physical contact with unfamiliar

adults.

The difficulty applying DSM-IV criteria clinically has been cited as one reason for the

paucity of peer-reviewed research on RAD (Zeanah, 1996). One proposal, argued for in a

series of papers, has been that there may be more than the two distinct subtypes of RAD

outlined in DSM criteria. An expanded set of alternate criteria for a series of attachment

disorders have been proposed and refined based on clinical case studies (see Zeanah, 1996;

Zeanah, Boris, Bakshi, & Leiberman, 2000). Detailed reviews of the difficulties applying

available diagnostic criteria have also been published (OConnor, 2002; Zeanah, Boris, &

Leiberman, 2000). Attempts to reliably diagnose classic RAD and the proposed alternate

forms of attachment disorders in high-risk samples have been limited; early results clearly

underscore the need for both continued revision of proposed diagnostic criteria and for

further research in this area (Boris, Hinshaw-Fuselier, Smyke, Scheeringa, Heller, &

Zeanah, 2004; Boris, Zeanah, Scheeringa, Larrieu, & Heller, 1998). Especially lacking is

data on the predictive validity of attachment disorders. In fact, the only available

longitudinal data are from follow-up studies of institutionalized children.

Both types of RAD have been described in institutionalized or formerly institutionalized

children, but the disinhibited type is by far the most prevalent (Chrisholm, 1998; Chrisholm,

Carter, Ames, & Morrison, 1995; OConnor, Bredenkamp, Rutter, & The English and

Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team, 1999; OConnor, Rutter, & The English and

Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team 2000; Smyke, Dumitrescu, & Zeanah, 2002). On

the other hand, only a small minority of children adopted from institutions continues to

manifest symptoms of either subtype of RAD over time. Those who remain symptomatic are

generally described as superficially sociable. These children often seek physical contact with

strangers. They may, for instance, climb uninvited into a strange adults lap and caress his or

her hair. On the other hand, caregivers often perceive affected childrens social connections

RAD in Maltreated Twins

65

to be shallow. Some exhibit hyperactivity and attention problems as well as difficulties in

peer relationships (OConnor et al., 1999).

An unforeseen trend, perhaps related to the lack of data on the course of RAD, has been a

fundamental reconceptualization of RAD by clinicians who publish outside the mainstream

scientific literature resulting in the application of revised diagnostic criteria to children older

than 5 years. Published claims that these revised criteria, which overlap with oppositional

defiant disorder and conduct disorder, yield population prevalence for RAD of 3 6% have

followed (Levy & Orlans, 1998). There is now a cottage industry in the USA of selfdesignated centers where attachment disorders are diagnosed and treated. Furthermore,

therapists of varying backgrounds are trained to recognize and treat affected children in their

communities, sometimes using unorthodox forms of treatment. Unfortunately, the use of

treatments involving physical restraint (i.e., holding therapy, re-birthing experiences)

have been documented to directly result in the death of at least six children during

therapy (Boris, 2003; Mercer, Sarner, & Rosa, 2003; Zeanah & OConnor, 2003). This

egregious misapplication of attachment theory underlying attempts to forcefully re-attach

children to their caregivers is of great concern and further demonstrates the need for

research on RAD and its sequelae.

The experiences of children who have been reared in institutions are not the same as those

children who have been maltreated within the context of one or more consistent caregiving

relationships. Children who present with RAD symptoms following maltreatment may have

a different clinical course than institutionalized children. Concerns about long-term effects

of maltreatment and attachment disruption date back to Bowlbys two papers on juvenile

thieves (Bowlby, 1944a, 1944b), however, to date there are no case reports or studies of

maltreated non-institutionalized children diagnosed with RAD who have been followed

longitudinally.

Case report of maltreated twins

Fraternal twins, Claire and Bobby, were placed in foster care when they were 18 months old

following allegations of neglect, including parental lack of adequate supervision of the

children and an inability to maintain adequate housing. The studio apartment was found to

be filthy (dirty diapers scattered about the home, human waste in the bathtub and on the

bathroom floor, trash lying about the apartment) and overcrowded (as many as nine people

were living in the apartment at once). The twins 3-year-old sister was reported to have been

left to play unattended on a second floor ledge and seen climbing on the balcony railing.

A brief placement with relatives had failed just prior to their coming into care. They were

first assessed by an Infant Mental Health (IMH) intervention team providing intensive

services to foster children less than 4 years of age (see Zeanah & Larrieu, 1998, for a

program description). Within a 21-month period, between 6 and 27 months of age, the

twins were moved 11 times, placed in a total of five different foster homes, and eventually

adopted by relative (see Table I for a timeline of placements, assessments, and key events).

Evaluation and treatment recommendations

The IMH team evaluated the twins 6 weeks after placement in foster care; during this time

the children had weekly 1 hour visits with their biological parents. The team observed the

twins in both structured and unstructured evaluation paradigms, in both home and clinic

settings, with both foster and biological parents. The twins exhibited many concerning

behaviors initially (see Table II; see also Hinshaw-Fuselier et al., 1999) and throughout their

. In-home intervention unsuccessful

. Twins and older sister placed in kinship care with paternal aunt (1st foster home)

. Kin placement fails (family is evicted from home)

. Twins and older sister placed in non-relative foster care (2nd foster home)

. Therapeutic visitation with

biological parents begins

. Children start at a child care center

. Burns found on twins hands

. Older sister removed after 1 week

. Ms & Mr. 5th foster home requested

removal of children due to maternal

aunt and uncles interest

. Biological mother made allegations of

sexual abuse against uncle (Mr. Z)

. Allegations not substantiated; appeared

biological mother attempting

to sabotage placement

. Moved into 3rd foster home

. This is move number 3 for the children

. Children are transitioned back to

biological home with older sister

. This is move number 4

. Children are returned to 3rd foster home

. Also placed in respite care (4th foster home) on weekends

. These are move numbers 5 & 6

. Moved from 3rd foster home into respite

care home (4th foster home)

. Moved from respite care home to 5th foster home

. These are move numbers 7 & 8

. Children moved to aunt and uncles home (Mr. & Mrs. Z)

. This is move number 9

. Children returned to 5th foster home

. Twins returned to aunt and uncle

. This is move number 11

. Custody is legally transferred

to aunt & uncle (Mr. & Mrs. Z)

17 months

18 months

19 months

21 months

22 months

23 months

25 months

26 months

27 months

30 months

Prior to Infant Team involvement

. CPS provide in-home intervention due to lack of supervision, neglect, and inadequate living conditions

6 months

Event

Placement

Age

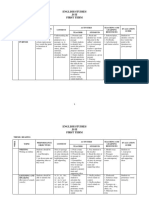

Table I. Timeline of placement, events, and assessments for the Smith twins.

(continued)

. Occupational evaluation of twins

occurs when twins are 32 months

. Developmental testing of twins

. Neurological evaluation,

included EEGs

. IMH team evaluation includes:

Home visits, WMCI, ParentChild

Interaction Procedure, Psychiatric

assessment with parents

Assessment

66

S. S. Heller et al.

Placement

. Twins remain with Mr. & Mrs. Z

. Twins residing with Mrs. Z

family has re-located.

Age

36 months

8 years

Table I. (Continued)

. Mr. & Mrs. Z report marital discord.

The couple has separated.

Twins still have visits with Mr. Z.

Event

.

.

.

.

.

cognitive screens (PPVT & KBIT)

parent report (CBCL & HBQ)

teacher report (HBQ)

child report (BPI)

attachment assessments (NSST & AEED)

Second research assessment includes:

. First research assessment includes

SSP & Attachment Interview

Assessment

RAD in Maltreated Twins

67

68

S. S. Heller et al.

Table II. X twins diagnostic behavior at time of evaluation (18 months).

Behaviors observed in the foster home

Behaviors observed in the clinic

Bobby

.

.

.

Flat affect

Socially indiscriminant

No verbalization or intentional

communication

. No preferred attachment

. Disorganized attachment behaviors during

separation and reunion with both biological

parents

. Developmentally delayed (tested at

12 13 month level, with language at 7 9

month level)

. Normal EEG and neurological exam

Claire

.

.

.

Flat affect

Socially withdrawn

No verbalization or intentional

communication

. No preferred attachment

. Disorganized attachment behaviors during

separation and reunion with both parents

. Developmentally delayed (tested

13 month level)

. Normal EEG and neurological exam

. Freezing episodes at times of mild

to moderate stress

Mrs. X with the

twins

Children were not observed with

biological parents in the home

at this time period as all visits

with biological parents

were supervised and in the clinic.

Mr. X with the

twins

. Alternates between dismissing childrens

attachment needs and angry preoccupation

. Difficulty reading cues and responding

contingently

. Unable to take responsibility for plight

of children

. Repeatedly missed appointments to see kids

. Dismissing of attachment needs of children

. Low level of interaction; minimal

shared affect

time in foster care. One of the teams recommendations was to increase supervised visitation

to twice a week; unfortunately, Mr. and Mrs. Xs attendance remained inconsistent

throughout their treatment. The parents had difficulty viewing the world from their childs

perspective. For example, Ms. X reported that her 19-month-old twins were easy to care for

as she just had to give them a few toys and they would entertain themselves all day long in

the playpen. Additionally both parents reported that they felt the twins were too young to

know what was going on in regards to the separation from their parents.

At the teams first home visit with foster family two, Bobby and Claire exhibited flat affect

and blank facial expressions and they appeared to be delayed in their development (e.g., few

verbalizations, no intentional communication). While Claire was emotionally withdrawn,

Bobby was socially indiscriminant (e.g., reached out to be held by the clinicians when he

first met them and cried inconsolably when they left). Neither twin demonstrated preferred

attachment behaviors with either their biological parents or their foster parents. Moreover,

when the twins were separated from their parents during evaluation procedures, both

showed strong indices of disorganized attachment upon reunion (Main & Solomon, 1990;

our observations of key reunion behaviors have been confirmed by coders masked to the

clinical history of the twins). At reunion, both twins exhibited heightened distress with

aborted approaches (e.g., approach mixed with avoidance). Claire also had stereotypies,

anxious or fearful facial expressions and prolonged freezing on reunion. The discrete

freezing episodes, during which she was unresponsive to auditory, visual, and tactile

stimulation, were evident in multiple contexts and were noted to increase following visits

RAD in Maltreated Twins

69

with the biological parents or a move to a new foster home. Once stabilized in a new home

setting the freezing episodes would decrease.

In addition to the host of social emotional disturbances, developmental testing confirmed

that the twins were significantly developmentally delayed. Neurological evaluation included

negative sleep-deprived EEGs and, beyond global developmental delay, no evidence of

neurological abnormalities.

The IMH team conducted a thorough evaluation with the twins biological parents, Mr. &

Mrs. X. Both parents were administered the Working Model of the Child Interview (Benoit,

Parker, & Zeanah, 1997; Zeanah & Benoit, 1995). This is a semi-structured interview that is

designed to assess caregivers internal representations, or working models, of their

relationship with a particular child. Separate interviews are administered to each caregiver

regarding each child. Mr. & Ms. X were also observed in a semi-structured interactional

procedure with each child (Heller et al., 1998). This interaction included periods of free play

as well as episodes where the parent is instructed to help the child complete developmental

tasks of increasing difficulty (e.g., stacking blocks or putting shapes in a shape sorter).

Ms. Xs assessment. Ms. Xs interview about her relationship with Claire was marked by

inconsistency. She tended to use generic terms to describe both Claires personality and her

relationship with Claire and had a very limited ability to recall specific stories to support her

descriptions. For instance, she used the same Christmas morning story on numerous

occasions. As evidenced in the following excerpt from her Working Model of the Child

Interview, Ms. X was eager to talk about her daughter, but seemed unable to present a clear

picture of her relationship with Claire:

Interviewer: What do you feel is unique or different about Claire compared to what you

know about other children?

Ms. X: She does a lot more than other children do that are her age.

Interviewer: What do you . . .

Ms. X: Umm, she is very playful and hyper. Like I see the difference between Bobby and

Bobby umm Claire. He is mellow, he likes being by himself . . . he likes watching his TV

and just being alone. Claire likes being around everybody. She plays better by herself at

times. Umm she likes just being with everybody. A lot of kids are shy and stuff like that

around new people but she is not.

As with Claire, Ms. Xs descriptions of Bobby and her relationship with Bobby were

inconsistent. For example, she reported that Bobby had a bad temper, yet later in the

interview she stated that Bobby did not get emotionally upset. When she was pushed for

detailed episodic memories, her responses became generic. She described Bobby as being

like other children his age and was unable to provide specific stories to support her

descriptions of Bobbys personality or of her relationship with Bobby.

Ms. X had very little insight about the effects of her experiences on herself or her children.

She described harrowing details of extreme family violence, including her stepmother

stabbing her father. Her reports of her chaotic and frightening childhood were detailed

and delivered in a tone that vacillated between matter-of-fact and overbright. However, when asked about how her childhood experiences affected her, Ms. Xs face became

expressionlessshe stopped speaking and she lost track of the interview. After a moment

Ms. X appeared to return to the present, asking the interviewer to repeat the question.

She then responded, in a very flat tone, that her childhood experiences did not affect her

at all.

70

S. S. Heller et al.

In the parent child interaction procedure, Claire rarely initiated any interaction with

her mother and avoided eye-contact throughout the 40 minute procedure. When Claire

struggled on any of the tasks she did not turn to her mother for help. Throughout the

procedure Ms. X offered vague instructions in an overbright tone and provided very

little praise. Claire, for the most part, was unresponsive to any of Ms. Xs overtures.

Ms. X was observed to vacillate between overbright and detached affect in her interactions

with Bobby. His general affective tone fluctuated between being flat and irritable. When

upset, Bobby gave mixed cues as to whether he wanted or did not want his mother, for

example he signaled for contact and then immediately rejected it. Ms. Xs response to

Bobbys fussing would be to infantilize Bobby (e.g., holding him like a newborn) and to get

increasingly intrusive with teasing and at times sexualized behavior (e.g., tickling Bobby or

holding him to her breast).

Mr. Xs assessment. Mr. X was withdrawn and anxious in the presence of the clinicians and

his children. His childhood was characterized by loss and rejection: his mother abandoned

him when he was 2 years old, his father was critical and cold, and his stepmother was

physically abusive. Mr. X had a history of learning disability and difficulty maintaining a job.

He was diagnosed with major depression, chronic early onset dysthymia, and developmental

learning disorder.

Like Mrs. X, Mr. X demonstrated a very poor understanding of his children and the way

in which his experiences affected himself and his children. Mr. X provided a very

impoverished and ambiguous picture of his daughter and their relationship, despite the fact

that both parents referred to Claire as daddys girl. Mr. X stated that he did not have

much influence on Claire or her development.

Similar to his interview regarding Claire, Mr. X provided a sketchy and generic picture of

his son, Bobby, and his relationship with Bobby. His descriptions of Bobby were repetitive

and he had great difficulty coming up with five distinct adjectives that captured his

relationship with his son. When asked to provide specific examples to support the adjectives

chosen, his examples were limited and he became increasingly frustrated with the interview.

In the following excerpt, Mr. X is describing why he chose the word happy to characterize

his relationship with Bobby:

Mr. X: Well aaa hes always happy because aaaa he keeps himself happy . . . he keeps

himself occupied or whatever. Or he does something that makes him happy about himself,

if he does the right thing or whatever.

Interviewer: Do you remember a specific time?

Mr. X: He was playing with lego blocks one time and he, like he had trouble putting the

blocks together and he finally got them together and he was happy about it (shrugsflat).

And he come running up to me and Im like there you gostart putting more on. And

hell go back and start putting more on. Hes happy for himself. Hes proud that he finally

figured out how to do it. He does something right he gets himself happy.

The overall tone of the interview was one of detachment; for example, Mr. X reported that

Bobby was just like any other child and was unable to present his child as unique in any

way. His relationship with Bobby, therefore, appeared shallow. His interview about Claire

was similar.

Mr. X was observed to have little emotional connection with his children; the dyads

demonstrated low levels of interaction and shared affect. Claire was self-directive and

focused on the tasks in the parent child interaction procedure. She exhibited minimal

RAD in Maltreated Twins

71

interest in interacting with her father and was typically unresponsive to her fathers rigid and

repetitive attempts at encouragement or assistance; she spent long periods of time engaged

in tasks and ignoring Mr. Xs bids.

In contrast, Mr. X diligently attempted to engage Bobby throughout the parent child

interaction procedure. As with his daughter, however, Mr. Xs attempts to support his son

were rigid, repetitive, and unsuccessful. Bobby, in response, appeared unfocused, dazed,

frustrated, and was unable to use his father for emotional or instrumental support.

Mr. and Mrs. Xs marital relationship was historically volatile (the two were separated at

the time of referral) and admitted to past bi-directional aggression. The dyad also had a

history of chronic and severe financial problems.

Following the evaluation, the IMH team determined that a stable placement with

consistent and sensitive care was the most important treatment goal for the children, in

order to facilitate developmental progress and social-emotional health. As the plan with

Child Protective Service (CPS) was to work toward reunion with the biological parents,

many of the initial treatment recommendations focused on Mr. & Mrs. X individually,

together, and with their children.

Post evaluative course

Though a stable and sensitive caregiving environment was considered imperative for the

twins, a series of unforeseen circumstances led the twins to experience five different foster

placements and 11 moves between the ages 6 and 27 months. When the twins were in a

stable and sensitive caregiving environment they exhibited less behavioral symptomatology

(e.g., food stuffing and aggression), rapid developmental gains, and shifts in attachment

behavior (e.g., increased comfort seeking and decreased freezing). For a more detailed

history of the X familys treatment and the twins placement history see Hinshaw-Fuselier,

Boris, & Zeanah (1999).

When the children were 30 months old, Mr. & Mrs. X surrendered their parental rights

and legal custody of the twins was transferred to the maternal great uncle and aunt (Mr. &

Mrs. Z), who adopted them. Two months later, the twins were evaluated by an occupational

therapist who placed Claires developmental functioning at the level of a 23 month old and

Bobby slightly behind Claire. At that time, Mrs. Z reported behaviors in Bobby and Claire

that were characteristic of preferred attachment (e.g., seeking comfort in times of distress,

preferring comfort from the aunt over others, etc.). Additionally, their freezing episodes had

reportedly stopped occurring.

The IMH team maintains involvement with a family until the children are surrendered,

returned to their biological family, or freed for adoption and in a stable placement. In the X

familys case, once the parents surrendered their rights, the IMH team began working

toward treatment termination. Fortunately, the team received research funding that enabled

them to follow-up on the twins progress and development at two different time points, aged

3 and 8 years.

Follow-up at 36 months

At 36 months of age, the twins and Mrs. Z (the adoptive mother) consented to participate in

a clinical assessment as part of a research project. Although the children clearly used Mrs. Z

as their primary attachment figure, each child demonstrated concerning behaviors. The

authors, as well as an independent coder blind to the twins maltreatment status, noted the

disordered attachment behaviors. Claire strived to control the interaction with her caregiver

72

S. S. Heller et al.

in either a punitive or caregiving manner. The shift, observed in Claire, from disorganized

attachment behaviors in infancy to controlling attachment behaviors in the preschool period

have been documented in other dyads in the attachment literature (Main & Cassidy, 1988;

Wartner, Grossmann, Fremmer-Bombik, & Suess, 1994). Main & Hesse (1990) have

proposed that this developmental shift, from disorganized to controlling, occurs out of the

childs need to take a parental role in the relationship. This need is believed to occur when

the parents own caregiving strategy is disorganized due to the parents history of loss or

trauma. Claires behavior with her adoptive mother suggests an internalized expectation that

her caregiver requires emotional support.

Bobby was repeatedly observed to engage in self-endangering behaviors and often laughed

when he performed dangerous feats (e.g., empty laughter after jumping several feet off a

platform into a tire tunnel and landing hard on the ground). Although self-endangering

behavior has not been documented in the research literature on attachment disorders it has

been documented in the clinical literature (Boris et al., 2004). The same questions regarding

Claires continued disorganized/disordered behavior with her adoptive mother apply to

Bobby.

Although the twins had some age-typical dysarthria they were not notably cognitively

delayed. At the time of this evaluation, however, neither twin was formally tested.

Standardized measures used at the 8-year follow-up

When the children were 8 years old they participated in a comprehensive evaluation. The

twins and their adoptive mother had two 2 3 hour home visits at which time several

measures were administered. Typical cognitive screens (the K-BIT and the PPVT) were

employed, as were standardized assessments of child behavior using parent and teacher

report (the Health Behavior Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist). Some more

specialized measures were also used and an expanded description of these measures and the

purpose and analysis of each follows.

Capturing child self-report

A childs self-perceptions shape his or her behavior in school, at home, and in relation to

others. Research has demonstrated that attachment history (Green & Goldwyn, 2002;

Verschueren & Marcoen, 1999) and maltreatment history (Bolger, Patterson, &

Kupersmidt, 1998; Kim & Cicchetti, 2004; Vondra, Barnett, & Cicchetti, 1989) influence

childrens perceptions of their social competence, peer relationships, school functioning,

self-esteem, and psychological adjustment.

In recent years, the measurement of attachment has progressed beyond its original

emphasis on behavioral observations to include assessments of attachment security at the

level of representation (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). Based on Bowlbys conceptualization of the internal working model (Bowlby, 1973), researchers have devised methods

that provide access to the mental organization of attachment experiences. Internal working

models are organized memories of the way in which attachment needs have been responded

to by attachment figures. They function in the way that cognitive schemas do, to provide an

efficient means of prediction and interpretation of experience. The terminology Bowlby

chose for his concept, however, was intended to emphasize the potential for revision and

updating of memory in the face of new experience in attachment relationships.

Representational assessments of attachment are designed to provide the respondent with

an opportunity to reveal expectations of attachment relationships, typically stored in

RAD in Maltreated Twins

73

unconscious memory. Attachment security assessed through representational measures in

childhood has been correlated with a variety of measures of childrens social behavior with

peers and adults, as well as behavioral measures of attachment security to parents (see Page,

2001, for a review). The relatively recent emphasis in attachment research on the

representational level has provided new avenues for understanding the developmental

implications of attachment security. Despite the fact that Bowlby originally relied on diverse

fields of knowledge to formulate attachment theory, including the construct of the internal

working model, attachment research has only relatively recently begun to explore

intersections among previously divergent fields of inquiry. One such intersection has been

attachment research and social information processing. Within the attachment relationship,

through the expression of attachment needs and the accommodation of those needs by

attachment figures, children learn seminal lessons in basic social skills such as how to

accurately appraise the intentions and wishes of others, how to express ones desires to

others, and how to negotiate differences in relational goals (Ainsworth, 1992). These more

sophisticated negotiation and expressive skills are reflective of the later stage of childhood

attachment relationships referred to by Bowlby as the goal-corrected partnership.

Representational assessments of attachment, thus, can provide researchers with a wide view

of an array of social information processing skills, first learned in attachment relationships.

The Berkeley Puppet Interview (BPI). The Berkeley Puppet Interview (BPI; Ablow &

Measelle, 1993) was developed in response to concerns regarding the validity of

measurement tools capturing preschool and early school-age childrens self-perception

(Measelle, Ablow, Cowan, & Cowan, 1998). The BPI employs puppets to create a peer-like

exchange that holds the young childs attention. The interview has been formatted so that

for each item each puppet admits to one side of a two-sided contingency (e.g., one will say

I take things that dont belong to me while the other will say I dont take things that

dont belong to me and the first will ask the subject How about you?). The format of the

interview decreases the likelihood of response biases (e.g., social desirability or overcompliance). The puppets are gender neutral and with each question they alternately

endorse or deny a given symptom. Most children quickly follow the flow of the interview and

each child is given a chance at the end of a section to talk to or play with the puppets. The

examiner hides his or her face behind the puppets, using a playful voice and moving each

puppets mouth in relaying the queries. Videotaping of the interview allows for verbal or

non-verbal responses (some children point to one or the other puppet) accommodating for

the variability in young childrens expressive vocabulary.

The authors of the BPI created several modules to assess various aspects of a young childs

life. The twins were interviewed using modules focused on family life, school adjustment,

peer relationships, and psychological adjustment or symptomatology. To date there are no

published norms for the BPI, thus for the purposes of this paper Bobby and Claires scores

were compared to those of a group of maltreated peers, all of whom were placed in foster

care before age 4 years.

The authors of the BPI also developed a questionnaire, the Health Behavior

Questionnaire (HBQ), to be administered to parents and teachers. This questionnaire is

scored on four domains: emotional and behavioral symptomatology, impairment, adaptive

social functioning, and physical health. Items are rated on a 3-point scale and match BPI

scales (Essex, Boyce, Goldstein, Armstrong, Kraemer, & Kupfer, 2002).

The Narrative Story-Stem Technique (NSST). The NSST is a representational attachment

method originally devised by Bretherton and colleagues (Bretherton, Ridgeway, & Cassidy,

74

S. S. Heller et al.

1990) and was used in this study. Various forms of this measure have been referred to as the

Attachment Story Completion Task and MacArthur Story-Stem Battery, depending on the

selection of narratives.

In the NSST method, children are presented with up to 10 brief story-stems, each of

which depicts some familiar, mildly stressful situation (see Table III for a list of story-stems

used). The story-stems are enacted with the aid of props, to facilitate the childrens

comprehension of the story-stem. In this study, the props used were as reported in Page &

Bretherton (2001) consisting of a bear family (mother, father, two siblings the same gender

as the subject child, grandmother, and childrens friend) and several play furniture items

corresponding to the elements of the story-stem. After the presentation of the story-stem,

the child is asked to show and tell what happens next in the story. The childs response is

Table III. List of story-stems used with twins.

Story 1

Spilled Juice

The family is sitting at the table and the little child (Jane, Robert) reaches for

some juice and spills the pitcher on the floor.1

Story 2

Hurt Knee

The family is taking a walk in the park. Little (Jane, Robert) tries to climb a

high, high rock and falls off it, crying, Ive hurt my knee, Im bleeding!2

Story 3

Monster in Bedroom Its bedtime and the mother tells little (Jane, Robert) to go to bed. S/he goes

into the bedroom and cries out, Theres something scary in my room!

Theres something scary in my room!2

Story 4

Departure

The mother and dad are going to go on a trip for 3 days, and say

to the children, See you in 3 days, Grandma will stay with you.2

Story 5

Reunion

The mother and dad return from their trip.1

Story 6

Headache

The mother and little (Jane, Robert) are sitting on the couch watching TV.

Mom says she has a headache and she turns the TV off, and asks little

(Jane, Robert) for some quiet. The doorbell rings and its little

(Janes, Roberts) friend who asks to come in and watch TV because

there is a really neat show on.3

Story 7

The Bathroom Shelf

Part I: The two children are playing in their toybox and the mother comes in

and says she has to go to the neighbors, and the children are not to touch

anything on the bathroom shelf while she is away. The children resume playing

in the toybox. Little Jane/Robert cries, Ouch! I cut my finger, quick, get me a

Band-Aid! The older sibling replies, But mom told us not to touch anything

on the bathroom shelf. Jane/Robert replies, But my finger is bleeding!

Part II: the mother returns.3

Story 8

Threes a Crowd

The older child and friend are playing in the wagon. The younger child asks to

join them. The friend replies, If you let your brother/sister play, I wont be

your friend any more.3

Story 9

Broken Cup

The mom sits on the couch, crying. Robert comes in and the mom says, Im

so sad because I just broke the cup that you gave me.

Story 10 Play with Ball

Jane/Robert is playing with her/his ball with her/his friend, Mary/Pete.

Suddenly, the friend grabs the ball. Jane/Robert cries, Ouch! That hurt

my hand!4

From the Attachment Story Completion Task (Bretherton, Ridgeway, & Cassidy, 1990).

From the Attachment Story Completion Task (Bretherton et al., 1990), with revisions by Granot & Mayseless

(2001).

3

From the MacArthur Story-Stem Battery (Bretherton, Oppenheim, Buchsbaum, Emde, and the MacArthur

Narrative Group, 1990).

4

From Warren, Emde, & Sroufe (2000).

2

RAD in Maltreated Twins

75

then coded for themes of interest. Initial coding of the childrens stories was based on

established methods reported in previous studies with the NSST (Page, 2001). For the

purposes of this paper, the content of the two childrens narrative responses were evaluated

on the presence of various positive or negative interactions between story characters,

autonomous or negative depictions of individuals, enactment of attachment behavior in

children, parenting nurturance and discipline, and the presence of highly distorted or bizarre

elements. In addition, overall story coherence and the degree to which the child avoided the

story-stems were rated. Quantitative variables based on frequencies of response codes were

not analysed, as they normally are for larger samples, because comparisons between only

two children would be unlikely to be meaningful. The codes were used to provide a rough

guide in tracking the responses, and to facilitate qualitative analyses of the significant themes

the two children presented in their stories. The fourth author, who was blind to the twins

history and had previously demonstrated inter-rater reliability with Inge Bretherton, an

originator of the NSST, performed this analysis.

The Autobiographical Emotional Events Dialogue (AEED). Another approach to understanding childrens internal representations is to analyse co-construction of narratives with

their caregivers (Fivush, 1991). Through repeated experiences of narrative co-construction,

the child internalizes his parents communication style over time so that the parent is eventually able to structure the conversations with questions but allow the child to develop the

story (Snow, 1990). It is through this process that the child learns, and eventually internalizes,

a style or range of emotional expression. Parents who express a wide range of emotions

typically have children who develop an open style of emotional communication and,

conversely, parents who have a restricted range of emotional expression tend to have children

who have a limited range of emotional expression (Dunn, Bretherton, & Munn, 1987).

Securely attached children have been described as holding richer emotional dialogue with

their parent compared to non-securely attached children (Laible & Thompson, 1998). Male

preschoolers, who have disorganized attachment classifications, are significantly more likely

to exhibit non-open communication styles with their mothers than their male peers classified

as secure (Etzion-Carasso & Oppenheim, 2000). An emotionally open communication style

in a parent child dyad allows the child to process both positive and negative emotions and

experiences safely and without fear of rejection (Settles, 2003).

The Autobiographical Emotional Events Dialogue procedure (AEED) is a narrative coconstruction measure developed to assess attachment security in childhood. The authors

(Koren-Karie, Oppenheim, Chaimovich, & Etzion-Carasso, 2003) argue that, in a dyad

exhibiting an open style of communication, the parent helps the child to contain

negative emotion, provides structure and organization, encourages the childs involvement,

and ensures that the child completes the task feeling successful and confident. Dyads

classified as securely attached in infancy have been found to exhibit an emotionally matched

or open style of communication (Koren-Karie, Oppenheim, Chaimovich, & EtzionCarrasso, 2001).

In the AEED, mothers and children are presented with four cards, on each of which a

name of a feeling is written: happy, mad, sad, and scared (Fivush, 1991). Dyads are asked to

remember an event in which the child felt each feeling and to jointly construct a story about

each of the events. Conversations can be classified into one of four groups, one reflecting

Emotionally Matched dyads presumably showing a psychological secure base and

three reflecting Emotionally Unmatched dyads (labeled Exaggerating, Flat, and

Inconsistent) presumably showing a lack of a psychological secure base.

76

S. S. Heller et al.

Findings at 8-year follow-up

Cognitive screens and behavioral reports

Claire scored in the average range on both cognitive screens, although her adoptive mother

reported that Claire had learning difficulties. Bobby scored average in math abilities and

below average in verbal abilities. Mrs. Z reported that Bobby had been diagnosed with

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) for which he was receiving medication.

He had also been diagnosed with dyslexia and was currently receiving speech therapy.

Mrs. Z completed a Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) on both children. Claire scored in

the borderline range on the externalizing scale and in the clinical range on the delinquent

subscale. Some of the items Mrs. Z endorsed as occurring often with Claire were: lies and

cheats, steals outside the home, argues a lot, destroys things belonging to others, has temper

tantrums. Her mother also reported having found Claire smoking cigarettes on two separate

occasions. Claires teacher reported, Claire desperately wants friends. She is unable to

interact appropriately, denying her that privilege. She sometime borrows personal items

from potential friends but then takes the items home. She is constantly trying to create

friendships.

Based on her report, Bobby scored in the normative range on all behavioral scales.

Bobbys score on the attention problems subscale was considerably higher than his scores on

the other subscales although it remained slightly below the borderline range. Both Mrs. Z

and Bobbys teacher indicated that he had problems with fidgeting, being easily distracted,

and being impulsive.

Childrens reports using the Berkeley Puppet Interview

Claires Berkeley Puppet Interview. Claire had a tendency to endorse contradictory items

throughout her interview. She endorsed items in the ADHD spectrum (e.g., difficulty

paying attention, difficulty sitting still). In regards to her school performance she endorsed

negative items (e.g., I think I am stupid, other kids learn faster than me, other kids know

more than me) as well as positive items (e.g., I think I am smart, I am smarter than other

kids). This contradictory pattern was repeated in regards to her peer relationships. Claire

endorsed items reflecting difficulties with her peers (e.g., I do not have a lot of friends, kids

do mean things to me, I am a lonely kid) as well as positive peer behaviors (e.g., kids like to

sit next to me, I do not tease other kids, other kids ask me to play with them). Claire

reported separation anxiety symptoms (e.g., scared to go to sleep without parent by bed, not

like going places without parents, worry parents will go away and not come back) although

she also reported that she does not worry about her parents when she is at school and that

she does not get scared if her parents go someplace without her.

Claires scale scores tended to be similar to those of her maltreated peers. She differed on

only two of the symptomatology scales, depression and anxiety; on both of these scales she

endorsed less anxiety and sadness than her maltreated peers.

Bobbys Berkeley Puppet Interview. Bobby endorsed items that reflected his AHDD diagnosis

(e.g., difficulty sitting still, difficulty paying attention) yet he also reported that he liked

school and was happy there. He reported a number of worries (e.g., I worry a lot and I

worry that bad things will happen). Many of the anxiety items that he endorsed reflected

separation concerns (e.g., worry parents will leave and never come back or scared to go

places without his parents). Bobby reported some difficulty with his peer relationships (e.g.,

feels lonely, other kids dont ask him to play, is left out of games, and he fights a lot), as well

RAD in Maltreated Twins

77

as positive peer experiences (e.g., he has a lot of friends, kids like him a lot, and he helps

other kids).

Bobbys scores across the BPI domains, in comparison to the scores of maltreated children

who had completed the same intervention program, were similar, though he reported somewhat lower levels of depression, impulsivity, aggression, and school engagement than the

average scores endorsed by his maltreated peers.

Both children reported that their parents fight a lot and when their parents fight both

worried that their parents were mad at them. Marital conflict was, however, also widely

reported by their maltreated peers. Claire was less likely than her peers to perceive parental

resolution to those conflicts while Bobby was less likely than his peers to blame himself for

the conflict. Indeed, the Zs were in the midst of a contentious separation at the time of the

8-year-old evaluation; the childrens responses speak to the validity of the measure in that

they were comfortable with reporting information that is not socially desirable.

Childrens report using the Narrative Story-Stem Technique

Claires Narrative Story-Stem Technique. Claire presents several stories with unusually

frightening images, deceit, contradictory representations of parents, and incoherent story

structures. Despite the incoherent story structure and negative themes in her stories, Claire

does exhibit some positive elements, especially several representations of the mother as

authoritative disciplinarian and nurturer.

Injuries to children are enacted beginning with the Departure story. In the first scene that

Claire enacts in that story, the children go with the grandmother to the park where they

immediately fall and bloody their noses. There is no clear reparation for this injury. Soon

after this, the children deceive the grandmother by running away and then going to a store

and stealing candy. The grandmother then pursues and finds them, but the children are not

safe at this point because the stolen candy, which they ate, contained nails that get caught in

their throats. The grandmother then takes them to the hospital, providing at least some

sense of protection. Vulnerability suddenly returns in the Reunion story, where out of

nowhere a robber appears who almost kills the younger child. The police arrive and, after

some uncertainty, catch the robber.

The most dramatic enactment of vulnerability occurs in the Bathroom Shelf story where,

very abruptly, Claire re-introduces the deception theme with an enactment of the older child

smoking.

Examiner: And mom asks Jane, Jane, how did you get a Band-Aid on your finger?

Claire: (younger sister replies) Dad went to the store and bought me one, cause I cut my

finger.

Then (taking the older sister in hand) the sister was smoking, and she left the cigarette on the

ground and the house burned down (moves all off to the side)

(mother appears to ask) What happened, yall?!

(younger sister appears to reply) Oh, I dont know, but sister was smoking.

(mother) Daughter, what have you been doing (unintell.)?

(younger sister complains to mother) Now mommy, she made my toys get on fire. Mommy,

could you buy me a new toy?

(mother) Yes, sweetie, at the toy store. (moves all on table) She, um, fireman (unintell.)

Examiner: What did the firemen do?

Claire: Came and put the fire out . . . She went to buy her a toy (moves all across the table), a

Barbie, and she (refers to older sister) didnt get nothing . . .

78

S. S. Heller et al.

And for smoking, she died (lays older sister down) . . . And theyre at the funeral (holds

father, mother, and younger sister in front of older sister, then moves them across table) And they

got a new house . . . And they had another daughter (stands older sister up with the rest, now

apparently as new daughter).

So she died (takes younger sister and sets her apart from the others) but she wasnt smoking.

Then they had another daughter (now sets younger sister back with the rest, apparently as

another new daughter) and that would be her.

Examiner: But she (pointing to little sister) died too?

Claire: (nods and smiles) She had another daughter, she had two more daughters . . . Now

they have a happy family (holds all in hand) . . . happy ever after.

Abrupt plot shifts are especially evident in six stories, where seemingly unrelated plot

elements suddenly appear, typically characterized by highly emotionally charged themes

(four of these are very frightening, one is an enactment of stealing, and one is of the parents

wedding). The Departure and Bathroom Shelf stories (described above) provide perhaps the

most dramatic examples of this. In two other stories, a noticeable sense of detachment is

communicated at the end, when the children are placed lying down, looking at the sky.

Deception and/or stealing are prominent themes in the narrative representations in five

stories. In three of these stories, children deceive parents or grandmother (running away,

stealing candy, sneaking a cigarette, stealing money from the mothers purse). In Monster in

the Bedroom story, in contrast, the children apparently overhear the parents fighting and ask

for an explanation. The parents response to the children, however, is to deny that they were

fighting. Stealing is enacted in two other scenes by outsiders. In the Reunion story, a

robber threatens the family, and in the Wagon story, someone steals the childrens wagon,

which is later recovered.

Despite the presence of several unusually disturbing narrative representations, positive

family interactions are also enacted. The mother is particularly authoritative in the first three

stories (Spilled Juice, Hurt Knee, and Monster in Bedroom), taking charge of situations to

effectively manage childrens behavior. There are also unambiguously positive representations of family interactions in the Broken Cup and Ball Play stories. Empathic responding of

children to the mother is enacted prominently in the two stories (Headache and Broken

Cup) designed to elicit this response. Childrens attachment behavior toward the mother

(and to a lesser extent the father) is enacted most clearly in two stories only (Wagon and

Ball Play) however, in both instances, the children seek assistance to resolve disputes

with peers.

In several stories, in contrast, the father is represented as selfish, incompetent, and

infantile. In the second story (Hurt Knee), he appears as a rival of the children, climbing the

rock and, once on top, looking down and laughing at them, which makes the younger

daughter cry. In the Bathroom Shelf story, he uses the toilet (the only character who ever

does so), and it overflows.

In summary, Claire creates several positive images in her stories, notably of the mother in

authoritative roles and of children responding empathically to her. In contrast, however,

there are few representations of childrens attachment behavior, and there are several very

unusual enactments of very frightening images and of deceit, as well as very abrupt plot

changes which are typically accompanied by highly emotionally charged themes.

Bobbys Narrative Story-Stem Technique. Bobbys narrative responses were characterized

most notably by repeating representations of detached independent behavior, especially by

the younger child. In the first story, for example, the sequence of drinking juice, spilling it,

RAD in Maltreated Twins

79

and cleaning up is enacted in turn by each of the four family members, independently. Injury

is frequently associated with independence. In the second story (Hurt Knee), Bobby first

enacts the parents taking the child to the doctor. He then repeats the theme of injury to the

child twice and resolves these by having the child go to the doctors by himself. The theme of

injury and reparation enacted in the Hurt Knee story is repeated in the Headache, Bathroom

Shelf, Wagon, and Ball Play stories. The representations of injury in the last story (Ball

Play) are particularly noteworthy for their apparent incongruity with the story-stem.

Here, each family member becomes injured by breaking bones, and the mother is injured

worst of all.

Bobby: (Younger child and friend approaching parents) I hurt my . . . We hurt our hands.

And they went to sleep, cause they had a cast on their hands. (subject lies younger child and

friend down together)

Examiner: They had a cast on their hands?

Bobby: And then he goes, plays with the ball, basketball (enacts the older child bouncing the

ball) He plays basketball. And then, Owww. I broke my leg. And then he went, he broke

his leg, and got a cast (subject lies older child down with younger child and friend). And then

dad went, and played basketball (subject enacts the father kicking the ball)

Examiner: What is he playing?

Bobby: Kickball. And he broke his leg (father walks away). And he laid down and got a

cast (subject lies father down with others). Then the mom went to bounce the ball. Bonk

Bonk (The ball hits the mother on the head.) Ahhh, I got a headache. I broke (subject lies

mother down with the others) . . . and now . . . and they all broke the . . . everything on their

body. The end.

Unlike the other stories in which there are enactments of injury and reparation, this story

ends with the entire family injured and no reparation provided.

Representations of family members sleeping, as seen in the above example, are common.

In addition to the Monster story, in which family members do not appear to be able to

wake up, seven of the 10 stories end with family members sleeping. Solomon, George, &

DeJong (1995) reported that such representations of sleep were indicators of avoidant

attachment.

Despite the multiple injuries to family members and some chaotic representations of

family relationships (e.g., punitive role-reversals in the Wagon story), positive themes such

as reparation, parent nurturing, and childrens attachment behavior toward parents are also

common throughout Bobbys stories. In the Broken Cup story, a structure similar to the

repetition of injury and reparation seen in several of the earlier stories is enacted. In this

story, however, the repetition is of breaking a prized object, and each family member

responds to this in turn, expressing empathy and replacement of the object. Childrens

appropriate empathic responding to the mother is also prominent in the Headache story.

The Departure Reunion story sequence (which was the basis, alone, for an analysis by

Solomon, George, & DeJong, 1995) is characterized by initial withdrawal by the children,

followed by the grandmother providing nurturance and, when the parents arrive home,

exuberant proximity seeking and affection.

In summary, in Bobbys stories there is often a sense of disconnection in family

relationships, and repeated injuries occur in several stories. Almost always, injuries are

responded to in some way with reparation, attachment behavior is frequently shown toward

parents (especially the mother), parents are represented in nurturing roles, and the story

structures are, for the most part, fairly coherent.

80

S. S. Heller et al.

The childrens Autobiographical Emotional Events Dialogue

Claire and Bobby were both coded as participating in Unmatched-Flat dialogues. Flat dyads

are characterized by the lack of development of the stories and by their lack of involvement

and interest in the task. Mother and child may mention names of emotions, but there is

almost no development of the meaning of the emotion. The stories tend to be very short and

often mother and child cannot provide four stories and consequently cannot completing the

task. Mother and child do not seem to be bothered by their lack of ability to provide four

different stories, and the mothers do not try to refresh their childrens memory or to

encourage them to develop a story.

Claires Autobiographical Emotional Events Dialogue. A pattern of impoverished narratives was

evident between Mrs. Z and Claire. When Claire and Mrs. Z are talking about the happy

card, we get four different labels for happiness but none of them developed into a full story:

Mrs. Z: Happy

Claire: Im happy when I go to school.

Mrs. Z: When you go to school you are happy?

Claire nods

Mrs. Z: What else makes you happy?

Claire: Um, my friends.

Mrs. Z: And how about when you see your favorite person?

Claire: Ya!

Mrs. Z: Were gonna go see all your little friends soon. What else makes you happy?

Claire: When I go shopping.

Mrs. Z: When you go shopping? That makes me happy too. OK. Wanna go to the next

card?

In this short example it can be seen that the dialogue between Claire and Mrs. Z is very

limited and shallow. They did not come up with an episodic story concerning a happy event,

but rather mention titles for different events. The mother did not try to coax the child to tell

more details, and as a result it is not really known why, for example, she is happy in school.

There were no answers in the text, and neither mother nor child seemed to be bothered by

that. It seems as if naming an event as happy is the most they could do. Such an emotional

climate may convey to the child the message that she should not look deeper for reasons for

her feelings and that talking about emotions only means labeling events with the right

names.

Bobbys Autobiographical Emotional Events Dialogue. When Mrs. Z was talking with Bobby,

she did not help him construct full stories but rather appeared satisfied with adequate labels.

This is very obvious in their talking about the Scared card.

Mrs. Z: Scared.

Bobby: I am, I was, I am scared.

Mrs. Z: What are you scared of?

Bobby: Of the dark.

Mrs. Z: Of the dark?

Bobby: Yeah.

Mrs. Z: Do you know why?

RAD in Maltreated Twins

81

Bobby: Yeah.

Mrs. Z: Why?

Bobby: Cause I hate the dark!

Mrs. Z: You hate the dark? What else are you scared of?

In this short example it can be seen that Mrs. Z repeats Bobbys word and does not help him

to elaborate on the dark story or ask him to give more details relating to his feelings. She

accepts his statement that he hates the dark as a sufficient elaboration and continues to

another example without resolving the negative feelings of being scared of the dark.

Discussion

The long-term sequelae of RAD diagnosed in early childhood are unknown. The little

existing data on institutionalized children, most of who show little coherent attachment

behavior while institutionalized (Zeanah, Smyke, & Dumitrescu, 2002), suggest varied

outcomes once institutionalized children are adopted into families. While the twins followed

in this case experienced gross disturbances in early care, they were never institutionalized.

This is the first longitudinal case report of children diagnosed with RAD in early childhood

and seen in follow-up.

The twins early experiences were extreme, though not inconsistent with those

experienced by many young children placed in early foster care. The predictive validity of

a diagnosis of RAD, and of these associated behaviors, is unknown. This is partly because

measures for assessing attachment in middle childhood, by tapping into what Dodge and

Rabiner (2004) have called latent mental structures, have only recently been developed.

Both age-appropriate and validated measures of cognitive and behavioral functioning were

used as well as narrative measures of attachment to capture each childs internal experiences

and expectations for relationships.

One way to make sense of the data gathered on the twins at follow-up is to consider the

findings from a psychiatric diagnostic perspective and from a relational or social information

processing perspective (Dodge & Rabiner, 2004). From a diagnostic perspective, the twins

symptoms at age 8 years were indicative of differing trajectories, most likely because their

symptom complexes had always been different. For each, symptoms were evident by both

parent and self-report.

Claire was reported by her mother to be evidencing delinquent behavior, a concern also

raised by her teacher. Her self-report on the Berkeley Puppet Interview was inconsistent

across most domains of functioning, but the themes of her story-stem responses included

delinquent acts and deceit and she even portrayed a young child smoking, a specific act her

mother had been concerned about. She endorsed lower levels of anxiety and depression than

a group of maltreated peers who were also placed in foster care before age 4 years and

followed as part of a larger study. Whether this represents the kind of affective disengagement

typical of children with early conduct disorder is unclear. What anxiety she did endorse, like

her brother, concerned separation.

Bobby endorsed symptoms of ADHD and Developmental Reading Disorder through the

Berkeley Puppet Interview; his mother endorsed attentional deficits and impulsivity on the

CBCL as well and his cognitive screen documented below average verbal abilities.

Social information processing (or social cognitive processing) refers to the engagement of

mental representations in social situations (Dodge & Rabiner, 2004). Discerning

how mental representations then influence social behavior is an important goal of research

in the social information processing area. Both the Narrative Story-Stems Technique and

82

S. S. Heller et al.

the Autobiographical Emotional Events Dialogue, as described above, require narrative

responses, which are then recorded and coded. Claires narratives were compelling in light

of the reports of her adoptive mother and teacher about her behavior. Her mother reported

behaviors above the clinical cutoff for delinquent behavior on the Child Behavior Checklist

and her teacher viewed Claire as desperately want[ing] friendships, though her

interactions with peers were conflictual. The themes of half of her narratives centered

around deception and/or stealing. Her stories were marked by abrupt and confusing plot

shifts with calamitous events suddenly befalling the children. The children in her stories

were portrayed as being very vulnerable yet they were also deceitful and ended up

experiencing much unpredictable calamity. Interestingly, her self-report from the Berkeley

Puppet Interview was quite contradictory regarding her relationships with peers and her

fears about separation from her caregivers. She both endorsed and denied difficulty with

friendships and fear of separation from her caregivers. The co-constructed narrative with her

mother was marked by considerable emotional disengagement. It is likely this disengagement characterizes their relationship (e.g., narrative measures have been shown to have

moderate to high stability), though it is unclear how this pattern has been shaped by previous

history of interactions (e.g., Claires controlling behavior at age 3 years) or current events

likely to be distressing to both partners (e.g., the marital discord and separation).

Nevertheless, the combination of Claires externalizing symptoms, contradictory report of

current functioning, chaotic personal narratives, struggles with friendships, and emotional

disengagement with the caregiver she portrays in her narratives as most nurturing, result in a

clinical picture that is quite concerning.

Bobbys response patterns are interesting in several ways. First, despite his difficulties with

attention and verbal processing, his stories were reasonably coherent and highly developed.

His observed impulsive and self-endangering behavior at age 3 years is evident still at age 8

years even in the content of many of his stories which involve repeated injuries and

reparation of injures. Though he depicts nurturing of children by caregivers in his stories,

there is also a good deal of avoidance, with children acting autonomously to care for

themselves and family members sleeping rather than interacting. As the case with his sister,

the tendency toward avoiding emotional expression is also evident in Bobby and his adoptive

mothers shared narratives in which emotions were labeled with little elaboration such that

the experience of having an emotion remained undeveloped. His self-report of separation

anxiety symptoms is interesting in light of the relatively strong avoidance depicted in his

stories. Separation anxiety is certainly not unexpected, given his early history of multiple

placements and the contemporaneous separation of his adoptive parents; nevertheless, the

avoidant aspects of his narratives suggest that it might be difficult for him to directly express

this anxiety.

Each twin exhibited different patterns of behavior across time. For Claire, the sequence

consisted of extreme inhibition as an infant, controlling behavior as a preschooler, and

conduct symptoms with affective disengagement and peer relationship problems as a schoolaged child. Bobby was socially indiscriminate as an infant, self-endangering as a preschooler,

and had impulsivity and attention difficulties at 8 years of age. What seems clear is that life

stressors, from early neglect to later family discord, may have impacted each child

differently, perhaps due to underlying differences in temperament. The narrative measures

are helpful in tracking how early attachment disruption is associated with later expectations

about relationships.

It had been hoped to re-engage this family in treatment following the 8-year assessment of

the twins. Unfortunately, though the twins adoptive mother received feedback about our

research teams concerns, particularly about Claire, and agreed to individual and/or family

RAD in Maltreated Twins

83

therapy, she did not bring the children in for treatment (despite repeated calls). Our plan

was to begin with family assessment, especially given our sense, as reviewed by Byng-Hall

(1995), that attachment-based family work might be useful in targeting child behavior (see

also Safier, 2003). Of course, the separation of the adoptive parents is a clinical wildcard in

this case; without a comprehensive family assessment the options for clinical intervention are

very limited.

If Claires symptoms were not to improve with family-based intervention, one option

would be to adapt the work of Moretti, Holland, and Peterson (1994) who have shown

promising results using an attachment-based treatment for adolescents with conduct

disorder. One clinical quandary in attachment-based narrative work with children who

experienced early disruptions in care concerns the degree to which the therapist joins with

the child to create a new relationship. It has been argued that working through the caregiver

is most appropriate under these circumstances since the creation and eventual dissolution of

even a therapeutic relationship may be difficult for the child (American Psychiatric

Association, 1994). Given the relatively disengaged narratives co-constructed by each twin

with their adoptive mother, it is hard to know how reflective and open to change the adoptive

mother might be. Assessing reflective function through the use of further narrative

interviews with the adoptive mother would likely be useful in charting a course for

intervention (Oppenheim & Koren-Karie, 2002).

Strengths and limitations

The utility of the case study methodology in psychological research has been debated.

Critics of the case study consider the methodology to be unscientific because of its

dependence upon anecdotal and retrospective information, lack of control of extraneous

variables, and an inability to generalize findings. Conversely, others argue that the ability to

facilitate the discovery of aspects of a phenomenon in question represent a considerable

strength of case studies (Gilgun, 1991; Trepper, 1990). A considerable strength of this case

study is its longitudinal nature and the selection of subjects (e.g., maltreated siblings

diagnosed before age 3 years with RAD) of clinical interest. Remarkable associations were

found between measures at each age even when standardized follow-up measures coded by

reviewers masked to the childrens early history were used. Nevertheless, the findings

regarding the clinical course of these children only begin to shed light on the possible

outcomes of other maltreated young children with attachment disruptions before age 4

years. As OConnor (2003) suggests, more research on how early attachment relates to

patterns of development of high-risk children over time is necessary. This case suggests that

the use of standardized tools, including narrative measures, will help inform both research

and practice. The course of institutionalized children with early attachment disruptions has

been systematically studied recently. Comprehensive assessment of non-institutionalized

maltreated children in infancy and early childhood using observational and narrative

measures derived from attachment research is now possible. In the future, the use of school

age measures capturing both eventual psychiatric symptomatology and social cognitive

processing will enrich our understanding of how maltreated children develop.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the twins and their families for sharing their lives with us.

We would also like to express our gratitude to Charles H. Zeanah, MD, and all of his staff

and clinicians on the Tulane University Infant Team for their commitment to this family

84

S. S. Heller et al.

and other families exposed to maltreatment. And finally, we would like to acknowledge the

hard work and dedication of all the Childhood Behavior Study research assistants for

collecting the assessments discussed in this paper.

References

Ablow, J. C., & Measelle, J. R. (1993). Berkeley Puppet Interview: Administration and scoring system manuals.

Unpublished manuscript, University of California at Berkeley.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1992). A consideration of social referencing in the context of attachment theory and research.

In S. Feinman (Ed.), Social referencing and the social construction of reality in infancy (pp. 349 367). New York:

Plenum Press.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington,

DC: Author.

Benoit, D., Parker, K., & Zeanah, C. H. (1997). Mothers representations of their infants assessed prenatally:

Stability and association with infants attachment classifications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38,

307 313.

Bolger, K. E., Patterson, C. J., & Kupersmidt, J. B. (1998). Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who

have been maltreated. Child Development, 69, 1171 1197.

Boris, N. (2003). Attachment, aggression, and holding: A cautionary tale. Attachment and Human Development, 5,

245 247.

Boris, N. W., Hinshaw-Fuselier, S. S., Smyke, A. T., Scheeringa, M. S., Heller, S. S., & Zeanah, C. H. (2004).