Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Josie and Mucus Cycle

Загружено:

robert543Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Josie and Mucus Cycle

Загружено:

robert543Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Josie Learns About the Mucus Cycle

“Mum,” Josie said one day when they were alone. “How am I going to know

when I’m about to have a period?”

Her mum smiled at the unexpected question. “You won’t know first time

round,” she replied, “but don’t worry. First time round you’re more likely to get a small

amount of brown staining in your knickers. I remember when that happened to me and I

thought ‘What’s this? This isn’t blood!’ In fact it’s dried blood. Once your periods get

underway, the discharge becomes fresh and red. Even then it’s a discharge rather than a

sudden whoosh – it’s not like when you go to the toilet.”

“It must be a bit embarrassing, though, if you suddenly get blood appearing

when you don’t expect it!” Josie exclaimed.

“Well, it certainly helps to be tuned in to what is going on,” her mum replied.

“Periods when they first start can be a bit irregular but once they get going they

establish a pattern which you’ll quickly learn to recognise. That helps to get you

prepared so you aren’t caught unawares. If you mark off on a calendar when each period

begins, you’ll know when to expect the next.

“But even if your periods are not in a regular pattern,” she added, “the body has

some give-away signs, if you know how to look out for them. I don’t think I told you

about the mucus last time, did I?”

“Mucus, like when you have a cold?” Josie asked.

“I obviously didn’t. Yes, it is a bit like when you have a cold, but it comes as a

discharge from the vagina, like the period. And it happens around the time of ovulation.

You remember what ovulation is, don’t you?”

“It’s when the egg’s released,” answered Josie promptly.

“And can you also remember which hormone builds up in the blood before

ovulation?”

Josie wrinkled her nose and thought. “Oestrogen?” she asked.

“Well done. Yes, the build up of oestrogen in the blood tells the brain that the

egg is ready, and the brain then triggers ovulation. But the oestrogen has two other

functions as well. The first is in the uterus and the second in the cervix. Can you find

those diagrams I drew last time?”

1 © Louise Kirk 2009

Josie ran upstairs and

brought them down.

“Here you are, Mum,” she

said, sitting expectantly beside

her.

“I told you that, when your

period’s over, the lining of the

womb begins to build up again.

That’s how it forms a new nest

ready for a new potential baby.

Now here’s

ere’s the diagram of the

whole uterus,, with the ovaries, the

Figure 1: Female reproductive organs tubes, the uterus, the cervix and

the vagina.

“And here’s the cross-section

cross of the endometrium,, or lining of the uterus. Can

you remember why the egg cycle is drawn across the top?” she asked.

ask

“Because the follicle produces first the oestrogen and then the progesterone!”

said Josie,, looking pleased with herself.

“You’re right!”

said her mum. “So

you’ll

’ll remember that

the construction of the

nest happens under the

influence of the

hormone oestrogen.

There’s still oestrogen

about after ovulation,

and the nest goes on

being built up, but the

Figure 2: Cross section of endometrium, or lining of uterus, showing main hormone becomes

monthly cycle ...”

“Progesterone,” said Josie.

“And that’s given off by the collapsing follicle. OK. Now progesterone

stimulates the glands in the uterus lining so that they produce the fluids which will

nurture the tiny baby should it arrive. That’s how it gets the nutrition to live and grow.

gr

2 © Louise Kirk 2009

You can see all sorts of lovely liquids there, just ready to feed the baby, until suddenly,

whoosh! The follicle disintegrates, the progesterone levels in the blood drop

dramatically, and the lining of the womb begins to be shed. There’s the period all over

again.”

“It’s very interesting, Mummy,” Josie said, craning over the drawing. “But you

were going to tell me about mucus. Does that come from all those glands?”

“A good question, but actually it doesn’t. It comes from the cervix. Can you tell

me what the cervix is?”

“I know you said you

have to look after it,” replied

Josie, thinking hard. “You said

it was something like the

gateway of the uterus.”

“It is. You can see it

here in the diagram. It’s

actually part of the uterus and

joins the uterus to the top of the

vagina. It’s a bit like a tube and

measures about 1 ½ inches

long. It’s made of lots of

expandable material because

when a baby is born it has to

Figure 3: Cervix and its mucus stretch from being only about

an inch in diameter to being

wide enough to let the baby out.

“Can you see all those wiggly folds?” she went on. “They’re called crypts and

inside the crypts there are hundreds of glands which produce the mucus I was talking

about. They don’t only produce one kind of mucus – there are lots of different kinds.

The scientists are still discovering quite how many and what it all does. Anyway, I’m

going to keep it very simple and talk about the two basic types.”

She continued drawing round her diagram.

“Most of the time the cervix produces mucus which looks like this.” She pointed

to her right-hand diagram. “Can you see that it is made up of blocks designed to keep

things out? That protects the uterus from germs, and it also prevents any of the man’s

sperm reaching the uterus and the tubes.”

3 © Louise Kirk 2009

“Oh,” said Josie. “Does that mean that most of the time you can’t have a baby?”

“Well, the time of possible conception, when the man’s sperm and the woman’s

egg can join to become a new cell, is much shorter than that. You should be able to

work it out from what I told you last time.”

Josie thought hard.

“I’ll give you a clue,” her mum ventured. “How long does the egg live in the

tube after ovulation if it hasn’t been fertilised?”

“Umm, 24 hours?” Josie asked.

“Well done. Up to 24 hours and usually nearer 12. So that means that the actual

moment of conception, when the man’s sperm and the woman’s egg join together, can

only take place within 12-24 hours each month. But nature has extended the period of

time when an act of intercourse can lead to conception by something else. What else do

you think it could be?”

Alice looked really puzzled at this. “Can’t think!” she said after a bit.

“If you want to make sure that you catch a bus, and you only know roughly

when it will arrive, what do you do?” her mother asked.

Alice shrugged and said, “Arrive early and hang around, I suppose.”

“If sperm arrive early, that’s exactly what they do. They hang around and wait

for the egg. But they’re only able to do that round about the time that the bus is

expected, i.e. that the precious egg is

released. Normally, the sperm die pretty

quickly in the vagina, but round the time

of ovulation they can live for several days.

The reason they can do that is because of

this other kind of mucus.”

Josie looked again at the second

diagram. “Wow, Mum. It’s completely

different! Isn’t nature clever? And does

Figure 4: Picture of fertile cervical mucus under the sperm travel up all those channels?”

microscope

“Yes, it does. So the mucus acts

like a biological valve, open round the time of ovulation and closed at other times.

When oestrogen levels are high it opens, and when they are low it closes.”

4 © Louise Kirk 2009

“Mum, if you can only start a baby for such a short time each month, why does

everybody talk about using contraception?” Josie asked.

Her mum met Josie’s inquiring look. “There are various reasons, but I suspect

the main one is that most people don’t realise how clearly the body works and how easy

it is to read its language. Your dad and I only discovered about it recently and we were

so impressed with what we’d learnt that we made it our business to discover as much as

we could. Now, we want you – and your brother and sister – to know and respect the

full beauty of your bodies from the beginning.”

Josie’s mum paused and smiled. “Your generation is much luckier than mine

was. You see, a lot of the science has only been discovered quite recently, and even then

it hasn’t been widely taught.”

She looked down again at the diagrams in front of her. “When you’re older I’ll

teach you how to read all your fertility. But for today it’s enough to remember that there

are two main types of mucus. One nourishes and helps the sperm along, and the other

blocks it. There’s another big difference. The barrier mucus stays where it is in the

cervix. You won’t be aware that it’s there. But the stringy mucus – the mucus which

looks after the sperm – drips down through the vagina and is clearly visible on the

outside of the body. It appears as a sticky discharge, a bit like white of egg. Sometimes

it’s like a gluey white lump. You’ll come to recognise it. When I was young, nobody

ever told me about it. I remember seeing it and thinking there must be something wrong

with me! I thought I must have tape worms (I didn’t know what they were either)!

When you see it, you’ll know it’s a pretty good clue that you can expect a period in

about a fortnight’s time – you’ll get to know your own pattern.”

Josie looked up at her mum and gave her a big hug. “Thanks, Mum,” she said.

“You know, you’re the best mum in all the world!”

Diagrams with amended captions taken from Reproductive Anatomy and Physiology for the Natural Family Planning

Practitioner, Thomas W. Hilgers, m.d. (Creighton University), 1981 with kind permission of the author.

5 © Louise Kirk 2009

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elias 2Документ37 страницElias 2Mohammed Elias AlamОценок пока нет

- Catholic Union Event 10 Jan 14Документ1 страницаCatholic Union Event 10 Jan 14robert543Оценок пока нет

- Catholic Ism PosterДокумент1 страницаCatholic Ism Posterrobert543Оценок пока нет

- Prayer ProcessionДокумент1 страницаPrayer Processionrobert543Оценок пока нет

- March For LifeДокумент1 страницаMarch For Liferobert543Оценок пока нет

- Pri b7b Full PageДокумент1 страницаPri b7b Full Pagerobert543Оценок пока нет

- Closing Party 2011Документ1 страницаClosing Party 2011robert543Оценок пока нет

- Prayers For Vigil 2011Документ11 страницPrayers For Vigil 2011robert543Оценок пока нет

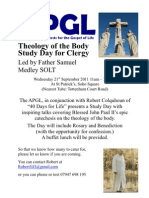

- Theology of The Body Clergy Study DayДокумент1 страницаTheology of The Body Clergy Study Dayrobert543Оценок пока нет

- Threats To Life at The Earliest Stages (Email Version)Документ30 страницThreats To Life at The Earliest Stages (Email Version)Robert ColquhounОценок пока нет

- Human Formation Seminars - Pornography Conflicts 2Документ53 страницыHuman Formation Seminars - Pornography Conflicts 2robert543Оценок пока нет

- Halfway Event October 2011Документ1 страницаHalfway Event October 2011robert543Оценок пока нет

- Instructions For The Prayer VigilaДокумент4 страницыInstructions For The Prayer Vigilarobert543Оценок пока нет

- Bulletin Pulpit Sept2011Документ1 страницаBulletin Pulpit Sept2011robert543Оценок пока нет

- Letter To Clergy-Autumn2011Документ1 страницаLetter To Clergy-Autumn2011robert543Оценок пока нет

- Madrid Party 2011Документ1 страницаMadrid Party 2011robert543Оценок пока нет

- 40 Days of Prayer For 40 Years of Abortion: A Daily Prayer Guide For Healing, Hope and RemembranceДокумент48 страниц40 Days of Prayer For 40 Years of Abortion: A Daily Prayer Guide For Healing, Hope and Remembrancerobert543Оценок пока нет

- 40 Days of Prayer For 40 Years of Abortion: A Daily Prayer Guide For Healing, Hope and RemembranceДокумент48 страниц40 Days of Prayer For 40 Years of Abortion: A Daily Prayer Guide For Healing, Hope and Remembrancerobert543Оценок пока нет

- William NewtonДокумент4 страницыWilliam Newtonrobert543Оценок пока нет

- Michael WaldsteinДокумент6 страницMichael Waldsteinrobert543100% (1)

- Peter ColosiДокумент6 страницPeter Colosirobert543Оценок пока нет

- Matthew PintoДокумент7 страницMatthew Pintorobert543Оценок пока нет

- Amenorrhea Ovarian TumorsДокумент18 страницAmenorrhea Ovarian TumorsJeremy ShimlerОценок пока нет

- Skema Jawapan Biology p2Документ12 страницSkema Jawapan Biology p2HenrySeow100% (3)

- Science 5: Learning Activity Sheet Modes of Reproduction in AnimalsДокумент4 страницыScience 5: Learning Activity Sheet Modes of Reproduction in AnimalsLena Beth Tapawan Yap100% (1)

- Sexual Reproduction of PlantsДокумент54 страницыSexual Reproduction of PlantsCIELY MUSAОценок пока нет

- Gen Bio 2 Summative Test Q4 Week 1 and 2Документ3 страницыGen Bio 2 Summative Test Q4 Week 1 and 2Daniel Angelo Esquejo ArangoОценок пока нет

- Chapter 12-Reproduction in PlantsДокумент4 страницыChapter 12-Reproduction in PlantsrajeshkumarkashyapОценок пока нет

- Reproductive SystemДокумент35 страницReproductive SystemlakshОценок пока нет

- BiologyДокумент28 страницBiologyrdgaefaОценок пока нет

- 10bja Medsci - Mckenzie CheyneДокумент60 страниц10bja Medsci - Mckenzie Cheyneapi-284323075Оценок пока нет

- Ipapasa Ito BukasДокумент2 страницыIpapasa Ito BukasAnjelica MarcoОценок пока нет

- InfertilityДокумент10 страницInfertilityHarish Labana100% (1)

- Gametogenesis and Fertilization: The Circle of SexДокумент85 страницGametogenesis and Fertilization: The Circle of SexAdityanair RA1711009010128Оценок пока нет

- Life Sciences - Reproduction and Endocrine System and HomeostasisДокумент83 страницыLife Sciences - Reproduction and Endocrine System and HomeostasisLusani NetshifhefheОценок пока нет

- How Do Organisms Reproduce TestДокумент1 страницаHow Do Organisms Reproduce TestManik BholaОценок пока нет

- DocumentДокумент89 страницDocumentRajeev Sharma100% (1)

- ContemporaryAgriculture, Vol. 62, No. 1-2, 2013.Документ139 страницContemporaryAgriculture, Vol. 62, No. 1-2, 2013.Бојана АндрићОценок пока нет

- 10 Science Imp Ch8 1Документ8 страниц10 Science Imp Ch8 1Rohan SenapathiОценок пока нет

- Profed102 Lecture 2Документ44 страницыProfed102 Lecture 2johnОценок пока нет

- Assisted Reproductive TechnologyДокумент14 страницAssisted Reproductive Technologyarchana jainОценок пока нет

- Basic Concepts of Sex, Gender, and CultureДокумент58 страницBasic Concepts of Sex, Gender, and CultureKipi Waruku BinisutiОценок пока нет

- Class VIII-Science-C.B.S.E.-Practice-PaperДокумент83 страницыClass VIII-Science-C.B.S.E.-Practice-PaperApex Institute100% (1)

- Passage PracticeДокумент13 страницPassage PracticeM3TZ .Оценок пока нет

- Ppt.x.reproduction 10 23Документ83 страницыPpt.x.reproduction 10 23ammara hyderОценок пока нет

- Chapter 16 AnswersДокумент6 страницChapter 16 AnswersindapantsОценок пока нет

- REVISION TEST - Sexual Reproduction in Flowering Plants - QPДокумент5 страницREVISION TEST - Sexual Reproduction in Flowering Plants - QPMohamed zidan khanОценок пока нет

- LESSON PLAn FertilizationДокумент5 страницLESSON PLAn FertilizationJane Tolentino33% (3)

- New Gcse: Foundation Tier Biology 1Документ15 страницNew Gcse: Foundation Tier Biology 1dao5264Оценок пока нет

- 2nd SECOND QUARTER EXAM IN GRADE 7 SCIENCEДокумент7 страниц2nd SECOND QUARTER EXAM IN GRADE 7 SCIENCEJenny Rose Bingil89% (9)

- CBSE Class 12 Biology 2019 Question Paper Solution Set 2Документ14 страницCBSE Class 12 Biology 2019 Question Paper Solution Set 2Yuvraj MehtaОценок пока нет