Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Psychogeography and The Macabre

Загружено:

EdemОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Psychogeography and The Macabre

Загружено:

EdemАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY AND THE Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

MACABRE

Reconnecting London to its Gothic literary

identity

Edem Makantasis

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

ii

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY AND THE MACABRE:

Reconnecting London to its Gothic literary identity

Edem Makantasis ACI 707998

March 2 Architecture

University of Portsmouth

2015

iii

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

iv

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

DECLARATION

UNIT TITLE: Unit 403 Critical Writing

TITLE OF ASSESSMENT: Psychogeography and

the Macabre: Reconnecting London to its Gothic

literary identity

DATE OF SUBMISSION:

I affirm that this Assignment, together with any

supporting artefact, is offered for assessment as

my original and unaided work, except insofar as

any advice and/or assistance from any other

named person in preparing it, and any quotation

used from written sources are duly and

appropriately acknowledged.

Name :

Edem Makantasis

Signature of Course Member:

Date:

22th January 2015

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

vi

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Abstract

Gothic Fiction is one of the most fascinating ways to tell a

story. Most people associate gothic with horror and the

supernatural, but I believe that's only the tip of the iceberg.

It is a wave of expression that gives people the opportunity

to manifest their thoughts and desires through art and

literature and explore these ideas beyond the boundaries of

our normality. Gothic novels had much success, especially

during late Victorian era. They managed to connect to the

people and produce some of the most famous narratives in

Literature like Dracula and Frankenstein. Themes about

fear, passion and forbidden desires were combined in

different and uniquely creative ways to offer a series of

emotions to the readers. Their connection and references to

existing London areas changed the way London was

perceived and eventually became part of city's identity.

However this is not the case anymore, as many features that

defined the Gothic are lost beneath the facade of modern

society. The written thesis will focus on the connection

between London and the Gothic, as well as the methods that

could help to bring back its macabre identity.

vii

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

vii

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my written thesis tutor Tina

Wallbridge for her support, guidance and patience during

tutorials and conversations and to Elizabeth Tuson as my

studio tutor for pointing me at the right direction during

early stages of the thesis.

I would also like to thank my parents for their continuous

support and trust in me all these years. I would not be here

if it wasn't for them.

Special thanks to my house mates for their psychological

support during the writing of the thesis.

ix

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Contents

Declaration v.

Abstract vii.

Acknowledgements ix.

List of Illustrations xii.

Introduction 1.

Psychogeography:

Defining psychogeographical fields 4.

The Surrealists and Situationists 5.

Derive, Detournement and the Flaneur 6.

Psychogeography today 11.

Gothic:

Cultural Linkages: Gothic Literature and British identity

16.

The Macabre 26.

Gothic Mapping of Victorian London 30.

The psychogeographical cases of Gothic London 37.

Conclusion 42.

Bibliography 48.

Sources of Illustration 50.

xi

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

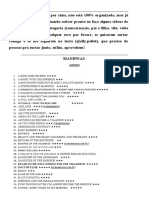

List of Illustrations

Cover Image-The Flaneur of London, Edem Makantasis, 2014

Figure 01- Map of Victorian London, Edem Makantasis, 2014

Figure 02-Strolling in modern London, Edem Makantasis, 2014

Figure 03- Psychogeographic guide of Paris, Guy Debord, 1955

Figure 04- The Naked City, Guy Debord, 1957

Figure 05- Le Flneur, Paul Gavarni, 1842.

Figure 06- The Labyrinth of Rotherhithe, Edem Makantasis, 2014

Figure 07- Over London by Rail, Gustave Dore, 1872

Figure 08- The Ghost of a Flea, William Blake, 18191820

Figure 09- A Suspicious Character, Illustrated London News,

October 13 1888

Figure 10- Spring Heeled Jack, Penny Dreadful, 1890

Figure 11- Penny Dreadful Illustrations,

Figure 12- Rain, Steam and Speed The Great Western Railway,

J.M.W. Turner, 1844

Figure 13- Illustration from The Mysteries of Udolpho, 1806

xii

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 14- The Nightmare, Henry Fuseli, 1781

Figure 15- Liverpool Street Station, London,1904

Figure 16- Map of Dracula in London

Figure 17- Map of Dracula in East End, London,

Figure 18- Map of Dracula in Piccadily

Figure 19- The Black Death

Figure 20- Gothic Literature and London map, Edem Makantasis,

2014

Figure 21- Crime Mapping in London, Edem Makantasis, 2014

Figure 22- Unite dmbiance in London, Edem Makantasis, 2014

Figure 23- Potential site for an Architectural intervention, Edem

Makantasis, 2014

xii

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

xi

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Introduction

Today's London is undoubtedly one of the most historical and famous

cities in the world with a metropolitan area of over 13 million people

and having been a major settlement for two millennia with a history

that goes back as far as the Roman empire. Its impact on the average

visitor, traveller or citizen, is huge. There are various aspects of London

that stay in our memories. These could be the architecture, the events,

the landmarks or the politics that come with a modern metropolis. All of

them, form an identity that defines modern London and our experience.

Most people who visit London already know what they want to visit, the

places they want to see and the streets they want to walk. There is this

pre-planned journey of London, or at least what modern media indicate

that London is. The whole experience becomes a series of missions. It is

a phenomenon that not only applies to tourists but also to Londoners.

As a tourist you have specific predefined routes that you will take and

as a Londoner you have your everyday routes that take you from your

home to your job and back again. The city is defined by its go to points,

and the journeys in-between are ignored. A good example would be the

underground system where you experience the start and the end of the

journey, but the rest is just a series of black blurry images or the

interior of the coach. The idea of an impulsive walk, driven by our

instincts and curiosity, is not there anymore. It is a shame considering

how many people were inspired by their experiences of such a journey.

These inspirations led to the birth of gothic literature. Charles Dickens,

Daniel Defoe and Robert Stevenson are just a few examples of this wave

of writers that were inspired by London's darkest secrets and corners.

The city gave and received. What? Another layer of identity of course. It

was an interaction that benefited both sides. On the one hand, it

provided the perfect atmosphere and mood to the authors, poets or

even artists. There were many places within the city that were haunted

by macabre images or stories. Darkness let the imagination run wild

and when that happens, it creates a need. This need to express

emotions and feelings, resulted in some of the best depictions of

London through gothic storytelling. On the other side, all these versions

of a dark and dangerous London, brought a new aspect of London that

would later fascinate people for generations to come. The urban

explorer took and gave back.

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

This interactive relationship has resulted in mapping London in

different ways, based on different interests, people and circumstances.

However, today it has become very hard to reveal that macabre side of

the city. The history of darkness, truth or fiction, is part of the history of

London. Nevertheless, the modern explorer may be influenced by a lot

of factors, but no longer by fear. The problem is not that there is an

absence of horror, but that it has stopped being a source of inspiration.

In a way, it seems reasonable since the appreciation of the macabre

doesn't come from appreciation of fear, but from the combination with

other feelings and emotions.

Since the macabre is not experienced these days, can we rediscover

that gothic vision in today's modern London? These are the main

questions that the thesis is going to focus on. It is very important to

understand the relationship between the voyager and his journey

through the urban environment and I will examine is psychogeography.

Most of the gothic literature about London was an outcome of different

interpretations of the walks and information obtained by the authors

through mapping of the senses and the emotions, which is more or less

the definition of psychogeography. According to Guy Debord "It's the

study of the specific effects of the geographical environment,

consciously organised or not."1. In the section 'Psychogeography' I'm

going to explore this further, because it is essential to know the history

and the basic ideas behind it, before it can be applied to the macabre.

The chapter is going to be divided, based on definitions, historical

groups and movements that were associated with it.

Cddc.vt.edu, 'Situationist International Online', 2015

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

In order to understand the background and the significance of the

Gothic narrative. 'Gothic' is going to look at how the darkest side

London was projected through history and literature by examining the

role of psychogeography during that period. I'm going to subdivide the

chapter again based on the definitions, it's connection to the British

identity, the literature and it's psychogeographical applications. This

process aims to find a method or strategy that might later be applied in

order to bring back that lost interaction. Once a formula is extracted, it

will be important to look at how the research can bring us closer to an

answer. The conclusion is going to suggest ways in which

psychogeographical ideas and architecture can cooperate by looking for

potential areas in London where the design thesis could contribute in

bringing back the interaction between us and the macabre.

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

iv

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Psychogeography:

Defining psychogeographical fields

Psychogeography is a term that is very hard to define. One could make a

quick assumption by saying that it's the point where psychology and

geography meet and he wouldn't be too far. Similar to the act of

walking, psychogeography can be described as :

.. a constellation whose three stars are the body, the imagination and the

wide-open world'2

Merlin Coverley refers to psychogeography as a term that resists

definition "through a shifting of series of interwoven themes and

constantly being shaped by its practitioners"3. Generally, it is a device to

be used by those who seek to reveal the true nature of our surroundings

within the urban environment that is hidden behind the flux of the

everyday. It has been used to generate a literary movement, a political

strategy, a representation of new age ideas and a set of avant-garde

practices and it is connected to famous movements and groups of

people like the Letterist Group and the Situationists International.

Although psychogeography can be traced back to the avant-garde

movement of the Letterist International and Guy Debord, it is the

variety of different interpretations, by the people who studied it, that

are most intriguing. A good example is the contrast between the

Surrealists playful approach and the Situationists scientific approach.

The first group used psychogeography as a device to transform our

'experience of everyday life and replacing our mundane existence with

an appreciation of the marvellous'4, while the second, under the

guidance of Debord, followed a 'more serious-minded attempt to

challenge the bourgeois orthodoxies of the day'5, which of course led to

the 'derive' and 'detournement', two techniques that have a big role in

the field of psychogeography.. Both terms are going to be explained

later.

Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust (Viking 2000)p212

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p10

4 Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p73

5 Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p23

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

The Surrealists and Situationists

Before basic psychogeographical terms are explored, it is important to

have a look at the historical movements and groups that interacted and

used psychogeographical terms and ideals. Two of the most important

were the Surrealists who were mostly associated with the flaneur and

the urban wanderer of the streets of Paris and the second one is the

Situationist group who focused on the explorational ideas of the British

urban environment and more specifically London.

Surrealism was a cultural movement of the early 1920s that was

expressed mainly through art and creative writing. It can be dated from

the publication of Andre Breton's 'Manifesto of Surrealism' in 1924 but

their relationship with psychogeography started earlier in 1918 when

Louis Aragon and Breton produced the psychogeographical novel.

Breton's defines Surrealism in his Manifesto :

'I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality,

which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a

surreality, if one may so speak'6

These notions would later find psychogeography as the perfect device

to challenge the public's perceptions with the 'flaneur', a term that is

going to explained in the next section.

The Situationists, however, were an organization with a more political

and straightforward way of seeing the world. They consisted of

intellectuals, avant-garde artists and political theorists and as a group

they 'developed an armoury of confusing weapons intended constantly

to provoke critical notice of the totality of lived experience and reverse

the stultifying passivity of the spectacle'7. They rejected the Surrealist's

idea of submission to the subconscious and the irrational force because

this type of imagination is 'poor' and lacks the element of surprise.

6

7

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p73

Sadie Plant, (1992) The most radical gesture p60

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Derive, Detournement and the Flaneur

One of the many terms that the Situationists created was the theory of

the 'derive'. According to their terminology :

'Derive is a mode of experimental behaviour linked to the conditions of

urban society: a technique of transient passage through varied

ambiances. Also used to designate a specific period of continuous

deriving'8

'In a derive one or more persons during a certain period drop their

relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual

motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the

attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. Chance is a

less important factor in this activity than one might think: from a derive

point of view cities have psychogeographical contours, with constant

currents, fixed points and vortexes that strongly discourage entry into or

exit from certain zones.'9

The main source of confusion with this theory was the contradiction

between the idea of the unplanned journey and the 'domination of

psychogeographical variations by the knowledge and calculation of

their possibilities'.10

Detournement was the second technique that was by the Situationists.

It was the act of using elements in a new and different way to promote

an agenda and in this case, that agenda was to transform urban life. The

official definition states:

'Detournement is integration of present or past artistic production into

a superior construction of a milieu. In this sense there can be no

situationist painting or music, but only a situationist use of these means.

In a more primitive sense, detournement within the old cultural spheres

is a method of propaganda...'11

Could the derive and detournement be used today as a strategy to

promote specific ideas and visions of the city? The Situationists

movement did it, but it did not focus enough on the subject. It is the

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p93

Debord G. (1958). Internationale Situationniste #2

Online at: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/theory.html. Accessed on 2/1/2015.

10 Debord G. (1958). Internationale Situationniste #2

Online at: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/theory.html. Accessed on 2/1/2015.

11 Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p94

9

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

urban wanderer who has to explore, feel and respond to his

experiences. In psychogeographical terms, this person is called the

'flaneur', 'mental traveller' or 'stalker' as he is both the subject and the

object of analysis.

'Flanerie is the activity of strolling and looking which is carried out by

the flaneur'12 who becomes a recurring theme in literature, art and the

metropolitan representation in fiction and real life. However the flaneur

is connected to his journey more romantic and artistic aspect of the city.

He sees art and he delivers art.

'..is the individual sovereign of the order of things who, as a poet or as

the artist, is able to transform faces and things so that for him they have

only that meaning which he attributes to them.'13

12

13

Keith Tester, The Flneur (Routledge 1994)p1

Keith Tester, The Flneur (Routledge 1994)p6

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 03- Psychogeographic guide of Paris, Guy Debord, 1955

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 04- The Naked City, Guy Debord, 1957

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 05- Le Flneur

10

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Psychogeography today

What about today? What is the significance of psychogeography today?

It is important to have a glimpse of the way it's been treated and used

these days in order to have an understanding of where did all those

theories and strategies lead today and how they can be reused. One way

to achieve that, is by taking a look at the work of modern

psychogeographers, especially those who played a big role in the revival

of psychogeography the last two decades. Ballard, Sinclair, Ackroyd and

Keiller contributed in the revival of the psychogeography in an effort to

deal with the banalisation of the urban environment. Literature was the

primary tool to accomplish that, and, once again, London was the

perfect setting. Along with its revival , they also brought back some of

the ideas and ambitions that were expressed earlier by the groups

associated with psychogeography, which were either adapted and

changed to fit the new reality, or were used as a reminder of the

historical past of the city. The way we studied the effect that the urban

environment had on the human behaviour was enriched, and at the

same time there were cases where a new elements of the modern

environment were included in the equation.

One excellent example of adaptation of the psychogeographical

principles to modernity is J.G. Ballard, who, in his book 'Crash', talks

about technology and the side effects of automobile transportation to

the act of wandering. In this case, his work has been called ambiguous,

mostly because he seems to have an positive attitude to the car, despite

his objection towards technology. This new freedom, that the car

provides, is celebrated by Ballard, as it provides a new mean of

transcending our surroundings. He also tried to capture the relationship

between human behaviour and new surroundings, and explained the

possible reasons behind the loss of connection between them.

Contrasting the Situationists, Ballard does not see any 'banalisation' in

the urban environment. On the contrary, he sees an extreme

atmosphere accompanied by violent and sexualised images and

describes these possible effects on the human behaviour as ' full-scale

descent into savagery, sexual perversity and the complete breakdown

of the idea of community'14. As a result of that, he ends up rejecting the

city of London as its heritage and history don't allow people to ' what's

really going on in life today'.

14

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p117

11

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

If Ballard succeeded in providing complexity and controversy to the

field of psychogeography, Ian Sinclair was the person responsible for

making it popular. Although he adopted some situationist ideas, he

decided to follow a more surrealist and traditional approach to

psychogeography. In his work he attempted to blend the occult with the

political, the hidden with the neglected and local with literary history,

resulting in the creation a new personal vision of London.

'I like their notion of finding a strange parks at the edge of the city, of

creating a walk that would allow you to enter into fiction'15

It is also essential to mention his rejection of the flaneur, as he

introduces us to the 'stalker'.

" Stalker is a stroller who sweats, a stroller who knows where he is

going, but not why or how"16

There are no more random walks without a known destination. He is no

stranger to this environment, and is aware of the transformation it has

undergone. One could say that the stalker fits the modern wanderer

better since we live in the age of media and we get bombarded by

information all the time. This makes the concept of being completely

lost within the city quite impossible. We are always aware of where we

are thanks to technology.

Peter Ackroyd, even though he didn't consider himself as a

psychogeographer, contributed a new way of experiencing and

understanding the urban environment. Like J.G. Ballard, Ackroyd

explores the extreme behavioural impact of the city on people. In order

to do that, he goes back to use a more gothic and dark side of London.

He sees the city not as a whole, but as a series of zones and areas that

are connected to events and activities. They will later create ' patterns

of interests and patterns of habitation so that the same kind of activities

emerge ..'17. These territories become something more than just a

machine that produces experiences. Like the detournement, if used

properly, they can transform people's experience of the city and change

their perception of these particular places.

15

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p121

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p120

17 Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p126

16

12

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

In an interview with film maker Patrick Keiller, he mentions that

psychogeography ' has divorced itself from political concerns and

obligations of the Situationists'18. Psychogeography in a way has come

full circle . Its practitioners concentrate more on the artistic aspect of it,

abandoning its true potential. The following statement that sums up

the unused capabilities of psychogeography today.

'Instead of seeking to change their environment, psychogeographers in

their contemporary incarnation seem satisfied merely to experience and

record it.'19

18

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p136

19

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p136

13

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

14

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

xv

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Gothic

Cultural Linkages: Gothic Literature and British

identity

'The term Gothic has three main connotations: barbarous, like the

Gothic tribes of the Middle Ages- which is what the Renaissance meant

by the word; medieval, with all the associations of castles, knights in

armour and chivalry; and the supernatural, with the associations of the

fearful and the unknown and the mysterious.'20

This definition sums up the word 'Gothic' in a very generic way and it

connects it mainly with fear and tales of terror. The term Gothic horror

may be connected to German Literature but the term Gothic Novel

originated in England. Although most of the novels explored the human

psyche in relation to the supernatural, later they also showed a

tendency to include imagination and feelings which run parallel to the

Romantic movement. The narratives and novels that carry the title

'gothic' represent and stimulate 'fear, horror, the macabre and the

sinister, within the context of a general focus on the emotional rather

than the rational'21. This preference towards emotions rather than logic

is quite important in order to comprehend the relationship between

British identity and Gothic literature.

20

Brendan Hennessy, The gothic novel (Longman for the British Council 1978)p324

Goodreads.com, 'Gothic Literature - Chat: Introduction to GOTHIC Literature (showing131of31)', 2015

21

16

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 07- Over London by Rail, Gustave Dore, 1872

17

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

During the industrial revolution technology and science dominated

England and changed it. The map of Britain was reformed as the cities

grew bigger and bigger and the landscape transformed from rural to

industrial. Within a few decades the majority of people moved to the

cities in a pursuit of a better life. However the pace of change was so

fast that people suffered an 'industrial trauma'. The continuous

development of science and the terrifying expansion of the industrial

areas led to a division between the crowd. While most of them were

fascinated by this scenario and could only see a bright future where

man is owner of his own destiny, some chose to reject it. The two

oppositional groups that are worth mentioning are: the ones who were

sceptical about technology and scientific discoveries and people who

became part of these new megalopolises but had difficulties adapting in

this new scary environment. As a result of this, Gothic was adopted by

the British in an attempt to either warn people about the repercussions

of the situation or provide an series of devices that will help them

adjust old traditions to the new place. Medieval principles, then, became

part of a nostalgia.

'Gothic presents itself as both a modern project that melts and

transforms traditional attachments in favour of new identities and as a

reaffirmation of authentic cultural values culled from the depths of a

presumed communal past'22

' Gothic novels reaffirm authentic cultural values culled from the depths

of a presumed communal past. They do this first by copying the ways of

the past, rather than breaking sharply with it. Further, Gothic novels do

more than rehearse the past; they figure that past as a lost Golden Age

that can be recovered.'23

22 Toni Wein, British identities, heroic nationalisms, and the gothic novel, 1764-1824 (Palgrave

Macmillan 2002)p4

23 Toni Wein, British identities, heroic nationalisms, and the gothic novel, 1764-1824 (Palgrave

Macmillan 2002)p4

18

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

One of the idealists who did not embrace the success of technological

advances was Mary Shelley who with 'Frankenstein' tried to show the

dangerous aspects of this progress. There is a symbolism behind the

portrayal of Viktor Frankenstein as the obsessed scientist who didn't

consider the consequences of his work. It represents the fear of an

uncontrollable science. William Blake shared the same fear in 'The

Ghost of a Flea', a painting that was inspired by a drawing of a flea

microscopically observed. In this example Blake actually uses a

scientific theme and makes it mysterious and strange. His quote is

representative of his views against the Enlightenment.

'Art is the Tree of Life. Science is the Tree of Death'24

24

Laocon: Jehovah & His Two Sons, Satan & Adam. An engraving of Laocon, the well-known

classical sculpture, is surrounded with many short, graffiti-like comments. These two sayings

are in the blank space to the right of the picture. This was Blake's last illuminated work.

Transcribed in William Blake and Edwin John Ellis (ed.), The Poetical Works of William Blake

(1906), Vol. 1,p435.

19

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

20

Figure 08- The Ghost of a Flea, William Blake, 18191820

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

The second explanation for the popularity of the Gothic Novels new

situation that was brought by the industrialization of Britain. Cities

were now attracting thousands of people coming from rural England

and the new industrial metropolis felt uneasy. There was a lot of

confusion and fear in this new environment as most people become

strangers to each other. This led to crimes, violence, tension and

poverty, in other words, the perfect setting for a new form of Literature

to feed from. Gothic narratives actually flourished within this macabre

scenery as they managed to sensationalize urban horror by adding

supernatural elements and using the language and imagery of the

Gothic tradition. These stories included : true crime stories, urban

myths, and Penny dreadfuls. The Jack the ripper murders were the most

famous of these crimes and were linked to the pre existing myth of

Spring-heeled Jack. Both cases managed to fuel a series of urban

legends that haunted the streets of London and later were used as

inspiration for a series of cheap fictional, horror stories that were

published in parts every week. They were named Penny Dreadfuls and

became quite popular with the middle class as they were easy to relate

to. In a lot of cases they eased up adult anxieties and even boosted adult

literacy.

21

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 09- A Suspicious Character, Illustrated London News, October 13 1888

22

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

23

Figure 10- Spring Heeled Jack, Penny Dreadful, 1890

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 11- Penny Dreadful Illustrations,

24

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 12- Rain, Steam and Speed The Great Western Railway, J.M.W. Turner, 1844

25

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

The Macabre

The macabre has been celebrated in London through gothic literature

and art, leading to a successful fusion between fiction and history as

part of the formation of the city's identity. Throughout history, people

were inspired by these visions of a dark and dangerous London to such

an extent, that they tried to reproduce their emotions and feelings

through strong narratives and the outcome of this inspiration was the

transformation of the urban setting.

To begin with, it is essential to comprehend the essence of the macabre

and what separates it from fear or horror. So instead of starting with

these visual re-enactments of the city it's better to concentrate on the

gothic in general and think about what is it that intrigues us about it. It

could be thrill of the unknown or a series of experiences that makes us

uncomfortable. It's a actually combination of all the aforementioned. In

his introduction to the history of gothic, Marcman Ellis gives three very

strong examples of the effects of gothic to the human psyche and how

they activate a series of reactions and emotions. Each of these examples

indicates different manifestations of the gothic. He starts with a

recorded experience by Barthelemy Faujas and his visit to John Sheldon,

a famous surgeon in London. His encounter with a beautiful and

carefully preserved body of a dead woman that the doctor had in one of

his cabinets triggered a feeling of confusion. A combination of a

beautiful but macabre image along with the logical explanation behind

the whole setting, can only be described as a 'disagreeable feeling' by

Ellis. On the one side there is this 'cool scientific gaze' and on the other

the 'tender emotions of love', all brought together in an picture of love

and pain. The same 'disagreeable feeling' is identified in his second

example, which is taken from the book 'The Mysteries of Udolpho'.

There is a part from the book, representative of gothic literature , where

the main character witnesses again an image of horror and dread

together with an innocent and instinctive curiosity. This combination of

wonder and terror is a feature of the gothic novel. The last example is a

painting by John Henry Fuseli, 'The Nightmare'. Once again, there is a

moment of terror and a moment of peace incorporated in the same

picture, haunted by the dark and heavy atmosphere.

26

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

'Gothic is not simply a narrative of terror or a set of properties, but is

also a tone or mood simply that is, in its own way, quite experimental... It

is interested in exploiting emotions, through feelings and thoughts'25

25

Markman Ellis, The history of gothic fiction (Edinburgh University Press 2000)p8-9

27

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

28

Figure 13- Illustration from The Mysteries of Udolpho, 1806

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 14- The Nightmare, Henry Fuseli, 1781

29

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Gothic Mapping of Victorian London

This section is going to explore how ideas and principles of the gothic

were applied within the city of London, with powerful and creative

storytelling. While in the previous section, the use of images and the

description of horrible and disturbing situations provoked these

conflict of contrasting emotions, here, it is the distortion and alteration

of the urban space that's intriguing. The reader experiences these

horrible places that the protagonists goes through but at the same time,

there is a subconscious thirst for more, as his curiosity increases. This

resulted in the birth of the urban gothic. According to Robert Mighall in

' A geography of Victorian gothic fiction' :

'The Urban gothic depicts scenes and places whose very existence may

appear to belong to the regions of romance but instead are found in

Midst of civilisation'26

The dark corners and areas of decay are perfectly shown in some of the

most representative pieces of literature in that era. G.W.M.Reynolds, in

one of the most famous penny dreadful novels, transforms parts of

London in such degree that he makes them unrecognizable. In

Mysteries of London, we get a taste of an uninviting version of

Smithfield Market, where the main character ends up. The descriptions

of his encounter with this area is quite graphic and the use of words like

'horrible neighbourhood', ' all dark and pitch' and 'foul and filthy' help

to intensify the atmosphere. Terror is a direct result of experiencing

this threatening and poor environment, 'a place of hideous poverty and

fearful crimes', 'a labyrinth' and these type of places became a model to

organise the city, its dark mysteries and secrets. It was an interesting

way of representing both architectural and civic fact and a poetized

image of London, mostly because it was a product of history, experience

and interpretation. Richard Maxwell tried to explain the representation

of the 'labyrinth' :

' The widespread tendency to see cities as mazes is a related but more

recent phenomenon, a product, I would guess, of historical memory.

Once Paris and London begin to be modernized - once streets are

widened and straightened to facilitate the circulation of traffic- the

older, usually poorer neighbourhoods exert a new fascination. Here

26

Robert Mighall, A geography of Victorian Gothic fiction (Oxford University Press 1999)p30

30

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

there are many narrow, winding alley; here traffic easily gets itself into

knots; here, the visitor who is not native may well be mystified.'27

Charles Dickens used the concept of the labyrinth to describe another

dangerous environment in Oliver Twist. The area in Rotherhithe, where

Russia and Surrey docks used to be, is depicted as the place where 'the

filthiest, the strangest, the most extraordinary of the many localities,

that are hidden in London wholly unknown, even by name, to the great

mass of its inhabitants'. Within this area, a maze is formed out of the '

narrow and muddy streets, thronged by the roughest and the poorest of

waterside people.'28 Washington Irving uses the same method to show

his protagonists journey to the centre of his labyrinth. In The

sketchbook of Geoffrey Canyon the main character, however, it is an

'oasis' type of place that he encounters at the end of it. A spot of peace

and safety that he had to find after experiencing 'weary flesh', ' bustling

busy throngs' and the ' obscure nookes and angles'.

The transformation, from poor and dangerous to dark and horrifying, is

necessary in order to create a degree of distance between reality and

fiction. What scares and at the same fascinates people, is the

observation of a place or a situation that should be familiar to them

because they have been there before, but it's not. The rule of a

disagreeable feeling resurfaces once again. Everything is presented to

them distorted and they find it difficult to accept the reality of the new

location and it confuses them. This is a method that is applied to both

literature and art manifestations of the gothic.

It is essential to achieve a contrast of feelings and emotions, for a gothic

novel to be considered successful. Reynolds's strategy to do this was to

follow a certain system of historical distortions. It is by presenting the

two extremes of the socioeconomical situations within the boundaries

of the city that he manages to relate the poor to the scary and the rich to

the safe. Middle class is either absent or under presented, and middle

class heroes don't figure prominently in his representations. There is no

place for grey areas, within the story. The light and the pitch black that

wealth and poverty represent contribute to a great effect to the

transformation of the Urban Gothic fiction. He explains :

27

Robert Mighall, A geography of Victorian Gothic fiction (Oxford University Press 1999)p3233

28 Robert Mighall, A geography of Victorian Gothic fiction (Oxford University Press 1999)p43

31

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

'There are but two words known in the moral alphabet of this great city;

for all virtues are summed up in the one, and all vices in the other: and

these words are: Wealth and poverty.'29

Gothic Fiction is full of cases of symbolism and representation of

socioeconomical values. Poverty and wealth were associated with

specific areas in London, like west end and east end. Gill Davies expands

on this by finding references within Bram Stokers Dracula where this

opposition is most notable and adds that while 'the West End was the

centre of the government, wealthy residences and leisure', the East End

'was the unknown England. the nether world, outcast London, the

abyss'30. London's most familiar and representative parts were being

invaded by this eastern unknown which in a way represented death and

disease both literary and metaphorically. An excellent example of this,

is the geographical placement of Dracula's castle in Purfleet in contrast

to the rest of the main characters who are staying west. Placing

Dracula's lair east of London actually enhanced his association with the

east end. It became easier to link him to all the immigrants and

foreigners, who in a way stood for countries and lands that were

connected with crimes mysteries and violence.

'West End with its government offices served as a site for imperial

spectacle: during her Golden Jubilee in 1887, Queen Victoria ... was

carted around the major thoroughfares, escorted by an Indian cavalry

troop. Meanwhile, another kind of imperial spectacle was staged in the

East End. The Docks and railway termini of the East End were

international entrerpots for succeeding waves of immigrants, most

recently poor Jews fleeing the pogroms of Eastern Europe'31

29

Robert Mighall, A geography of Victorian Gothic fiction (Oxford University Press 1999)p54

Davies G. (2004). London in Dracula; Dracula in London. Literary London: Interdisciplinary

Studies in the Representation of London, Volume 2 Number 1 (March 2004).

Online at: http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/march2004/davies.html. Accessed

on 2/1/2015.

31 Davies G. (2004). London in Dracula; Dracula in London. Literary London: Interdisciplinary

Studies in the Representation of London, Volume 2 Number 1 (March 2004).

Online at: http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/march2004/davies.html. Accessed

on 2/1/2015.

30

32

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

This is even more evident within Dracula, at the point when a west

ender, Jonathan Harker explores Carfax Abbey, Dracula's Lair in the

east:

'The place was small and close, and the long disuse had made the air

stagnant and foul. There was an earthy smell, as of some dry miasma,

which came through the fouler air. But as to the odour itself, how shall I

describe it? It was not alone that it was composed of all the ills of

morality and with the pungent, acrid smell of blood, but it seemed as

through corruption had become itself corrupt.'32

32

Robert Mighall, A geography of Victorian Gothic fiction (Oxford University Press 1999)p68

33

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 15- Liverpool Street Station, London,1904

34

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 16- Map of Dracula in London

35

Figure 17- Map of Dracula in East End, London,

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 18- Map of Dracula in Piccadily

36

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

The psychogeographical cases of Gothic London

All these notions and ideas of distortion of reality and context, came

from the authors' own experience. One has to experience, imagine and

interpret first and only then is he able to write and create. Such

experiences inspired a number of authors to create some iconic gothic

novels where psychogeography was used as the main tool to achieve a

re-imaging of the city. This section is going to have a deep look into how

psychogeographical surveys of London produced gothic fiction. The

need to explore this relationship becomes vital in order to make the

connection between psychogeography and macabre narratives.

Previous sections have examined how gothic novels were a

manifestation of political and social issues in London. Crime, violence,

fear and social degradation became the tool to the alteration of the city.

However, there was another highly important part of London's identity

that hasn't been mentioned in this analysis yet and its history. In 'a

Journal of the Plague Year', Daniel Defoe manages to transform the

familiar layout of the city by blending fact and fiction. A fictional

protagonist records his experiences in London during the Black Death.

As a theme, the plague belongs to London's darkest parts of history as it

wiped out about 15% of its population and provided a great setting and

lots of information that was eventually used in the novel. The portrait of

the city was a result of stories and other historical facts.

'... Defoe's account of the plague year of 1665 gathers the bare statistical

facts. the precise topographical details and the peculiar local

testimonies that were to become the hallmarks of psychogeographical

investigation and presents them in the non-linear and digressive fashion

that was later to characterise the drift of the Derive.'33

33

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p36

37

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

London became a place that was slowly being swallowed by decay and

death. Navigation within such an obscure and chaotic place was very

difficult. Unlike the Derive where the explorer takes these random drifts

through the city out of curiosity, here it's not his choice. He finds his

way by instinct and fear.

' Navigating this urban space in the 1660's could be tricky, both

physically and conceptually. There were no maps for ordinary people to

guide them through the city. You made your way by sight, by memory, by

advice, by direction and by luck'34

Coverley also adds:

' Only by re-learning the signs as they were rapidly deformed and

distorted by the passage of death and disease could Defoe's narrator

hope to survive the onslaught. Defoe reveals a 'sense of a haunted

geography' through which the progress of the plague is meticulously

documented'35

Although Defoe's novel was considered the first piece of literature that

contained a psychogeographical survey of London, it was Robert Louis

Stevenson who was hailed as the 'first psychogeographer' thanks to his

novel 'The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'. Here, Stevenson

managed to create a nightmarish place that would later provide the

most lasting image of the city and set the tradition of London Gothic

along with its most recognizable characteristics, the unreal and eternal

landscape.

34

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p37

35

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p37-38

38

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 19- The Black Death

39

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

While in the cases mentioned before, there is a opposition between

areas of London and classes of people, Stevenson's novel uses the

division between reality and appearance which based on the occult so

that he can 'expose the double life of privilege and despair lie in the city

of the late nineteenth century'36. Just like the protagonist's two-sided

personality, London seems to have a contradictory personality as well.

On the one side there is the dreadful image of the East end, and on the

other there is a dreamscape of Victorian facades of the west. The book

was also linked to the Ripper murders that happened the following year

and gave it an extra-literary existence. Although there is a difference in

the depiction of these areas, what's quite interesting are the similarities

between the city's and Dr Jekyll's deformation. In the book, there is a

strong example of a place's visual alteration just in front of the reader's

eyes.

'... for here it would be dark like the back-end of evening; and there

would be a glow of rich, lurid brown like the light of some strange

conflagrations; and here, for a moment, the fog would be quite broken

up, and a haggard shaft of daylight would glance between the swirling

wreaths. The dismal quarter of Soho seen under these changing

glimpses, with its muddy ways, and slatternly passengers, and its lamps,

which had never been extinguished or had been kindled afresh to

combat this mournful reinvasion of darkness, seemed, in the lawyer's

eyes, like a district of some city in a nightmare'37

So after the transformation, the reader witnesses an new, more savage

and primitive person, and the same thing happens to London. Mr Hyde

is the embodiment of Jekyll's hidden and forbidden desires. Desires and

thoughts that were there before but were suppressed under Dr. Jekyll's

consciousness. Only once the criminal is unleashed and the person 'goes

native'38 can we observe London's dark side. The symbolism behind the

darkness that is existent and waiting to be unleashed is quite obvious

and very relatable to both the Victorian and the modern metropolis. In a

theory that may be applicable to cities, as well, Robert Mighall examines

the protagonist's deformation by saying:

36

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p45

Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials 2010)p46

38 Robert Mighall, A geography of Victorian Gothic fiction (Oxford University Press 1999)p139

37

40

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

' The anthropological lowness of Mr Hyde is the inevitable product of

Jekyll's externalization of hierarchical structures according to the

specification of psychiatry and criminology'39

This explains to a great degree the need to explore the macabre aspect

of our urban surroundings. Just like Mr Hyde, it's part of London's

suppressed legacy and identity that no matter how disgusted or

ashamed we are by it, we can't get rid of it. So, the resurface of the city's

darkest history becomes inevitable and the fact that Britain at some

point was able to embrace it and appreciate it, shows that it is a strategy

that can be used even today.

39

Robert Mighall, A geography of Victorian Gothic fiction (Oxford University Press 1999)p147

41

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Conclusion

The strategy behind the dissertation was to understand the terms, the

philosophical ideas and ambitions behind Gothic Literature and

Psychogeography in order to extract a method that could be applied on

London today to bring back the appreciation for the macabre which has

been lost. Gothic and psychogeography had to be examined so that there

would be an understanding of the history and the reasons behind its

acceptance, compared to modern literature and perhaps help us look into

the right direction to its revival. There is still potential for Gothic narratives

to resurface and become once again part of London's history and identity.

The fact that they fed from fear and social anxiety of the middle class,

indicates that there are still the right circumstances for it to flourish.

One of the reasons behind our failure to embrace the hidden and the

undesired, comes from our inability to experience space the way we used

to. The city and its architecture do not interact with our senses the same

way they used to. We may blame technology but it is vital to understand

that architecture is capable of reactivating those senses which, along with

memory, can bring back that long lost desire for the unexplained, the

bizarre and the forbidden, only if it starts interacting with all our five

senses, our body and our subconscious. According to Juhani Pallasmaa,

Every touching experience of architecture is multisensory; qualities of

space, matter and scale are measured equally by the eye, ear, nose, skin,

tongue, skeleton and muscle... architecture involves several realms of

sensory experience which interact and fuse with each other. 40

Once that level of interaction between the person and his surroundings is

achieved, he will be able to experience more than what his vision allows

him to. He will be intrigued by the darker aspect of the city, the unknown

and the macabre. People have to be aware of the darkness to be able to

appreciate it.

40

Juhani Pallasmaa, The eyes of the skin (Wiley-Academy 2005)p41

42

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Deep shadows are essential, because they dim the sharpness of the vision,

make depth and invite unconscious peripheral vision and tactile fantasy .

41

These type of experiences leave an imprint on our memories and become

forever associated with the city and its identity. The same way that

memory can ' re-evoke the delightful city with all its sounds and smells and

variations of light and shade' 42 it can also bring back the city of the

macabre, the horror and awe.

It may not be realistic to change the city to accommodate such

transformation at once, but it is possible to use architecture as a tool to

trigger senses, emotions and feelings. An urban architecture that will

operate based on Peter Ackroyd's theory of a city of zones and areas that

create patterns of activity and ambiance. When the situationists demanded

a quality of architecture that went beyond the habitation and based on Le

Corbusier's unit d'Habitation , they sought for the unit dmbiance, which

was an area of particular intense urban atmosphere. Such areas are the

best candidates for an architectural intervention, that will attempt to bring

back London's Gothic identity, especially when they have a historical

connection with the macabre. It is possible to identify such regions within

London by applying Debord's method of mapping units of habitation in

Paris with the Naked City in three steps:

41

42

Juhani Pallasmaa, The eyes of the skin (Wiley-Academy 2005)p46

Juhani Pallasmaa, The eyes of the skin (Wiley-Academy 2005)p70

43

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 20- Gothic Literature and London map

1. Locate areas in Victorian London, so that we get an understanding of

what is a unit of macabre ambiance. Figure 20 shows where these areas

are, based on references from Gothic Literature like Dracula, Mysteries of

London, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Oliver Twist.

44

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 21- Crime Mapping in London

2.Locate areas of Modern London where similar type of dangerous

situations and encounters may happen. The map on Figure 16 indicates

regions of the city with the most criminal activity and is based on

Information from London metropolitan Police.

45

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 22- Unite dmbiance in London

3. Merge information acquired from previous maps to inform of

contemporary units of ambiance, that contain both historical background

associated with the macabre, but at the same time, has the potential to

provide London a new Gothic identity.

46

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 23- Potential site for an Architectural intervention

It is within these such Districts that architecture can contribute to the reappreciation of the macabre. People, who walk these streets, experience,

see and hear stories every day but they do not get the chance to record or

express any of those feelings and emotions that reveal the dreadful aspect

of their neighbourhood. That's where psychogeography and architecture

will intervene and create an interactive chain that will contribute to

London's Gothic identity. It is important to provide a centre where, with

the help of psychogeographical methods, urban wanderers will manifest

their experiences and memories into art and literature, just like Stevenson

or Dickens. A place where people will learn, produce and exhibit their work

that will operate at the same time as a monument of the Macabre and a

reminder that it is still part of London.

47

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Bibliography

Books

Coverley, Merlin,

2010).

Psychogeography (Pocket Essentials

Mighall, Robert,

A geography of Victorian Gothic fiction

(Oxford University Press 1999).

Hennessy, Brendan,

British Council 1978).

The gothic novel (Longman for the

Ellis, Markman,

The history of gothic fiction

(Edinburgh University Press 2000).

Tester, Keith,

The Fla neur (Routledge 1994).

Wein, Toni,

British identities, heroic nationalisms,

and the gothic novel, 1764-1824

(Palgrave Macmillan 2002).

Emsley, Clive,

2005).

Hard men (Hambledon and London

Pallasmaa, Juhani,

2005).

The eyes of the skin (Wiley-Academy

Sadler, Simon,

The situationist city (MIT Press 1998).

48

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Websites

http://www.literarylondon.org/londonjournal/march2004/davies.html

http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/psychogeography-merlincoverley/

http://www.cddc.vt.edu/

http://resources.mhs.vic.edu.au/creating/pages/origins.htm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L-5P4G1L36Y

http://www.geog.leeds.ac.uk/people/a.evans/psychogeog.html

http://www.casebook.org/dissertations/ripperoo-spring.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spring-heeled_Jack

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penny_dreadful

http://maps.met.police.uk/

49

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Sources of Illustration

Cover Image-The Flaneur of London, Edem Makantasis,

2014

Figure 01- Map of Victorian London, Edem Makantasis,

2014

Figure 02-Strolling in modern London, Edem Makantasis,

2014

Figure 03- Psychogeographic guide of Paris, Guy Debord,

1955

Retrieved from:

https://mappingweirdstuff.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/

debord-guide1.jpg

Figure 04- The Naked City, Guy Debord, 1957

Retrieved from: http://www.laciudadviva.org/blogs/wpcontent/uploads/2010/05/the-naked-city-1957-guydebord.jpg

Figure 05- Le Flneur, Paul Gavarni, 1842.

Retrieved from:

http://f1.bcbits.com/img/a1685681063_10.jpg

Figure 06- The Labyrinth of Rotherhithe, Edem Makantasis,

2014

Figure 07- Over London by Rail, Gustave Dore, 1872

Retrieved from: http://www.magazindomov.ru/wpcontent/uploads/2012/09/Archway-Studios-11.jpg

Figure 08- The Ghost of a Flea, William Blake, 18191820

Retrieved from:

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/blake-the-ghost-ofa-flea-n05889

50

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 09- A Suspicious Character, Illustrated London News,

October 13 1888

Retrieved from:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a1/Ja

cktheRipper1888.jpg

Figure 10- Spring Heeled Jack, Penny Dreadful, 1890

Retrieved from: http://hidden-highgate.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/09/springheeled-jack.jpg

Figure 11- Penny Dreadful Illustrations,

Retrieved from:

https://horrorpediadotcom.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/

jacktodd.jpg

Figure 12- Rain, Steam and Speed The Great Western

Railway, J.M.W. Turner, 1844

Retrieved from:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/96/T

urner_-_Rain,_Steam_and_Speed_-_National_Gallery_file.jpg

Figure 13- Illustration from The Mysteries of Udolpho, 1806

Retrieved from: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/3YUEhf7hQ6s/Up86ijlCnnI/AAAAAAAAEGQ/BNjdLKuRt7I/

s1600/Udolpho+-+the+ideal+beginning++from+1806+version+vol+3.jpg

Figure 14- The Nightmare, Henry Fuseli, 1781

Retrieved from:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/56/J

ohn_Henry_Fuseli_-_The_Nightmare.JPG

Figure 15- Liverpool Street Station, London,1904

Retrieved from: http://www.history-inpictures.co.uk/store/index.php?_a=viewProd&productId=8

471

51

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

Figure 16- Map of Dracula in London

Retrieved from: http://www.literarylondon.org/londonjournal/march2004/location.htm

Figure 17- Map of Dracula in East End, London,

Retrieved from: http://www.literarylondon.org/londonjournal/march2004/eastend.htm

Figure 18- Map of Dracula in Piccadily

Retrieved from: http://www.literarylondon.org/londonjournal/march2004/piccadilly.htm

Figure 19- The Black Death

Retrieved from:

http://www.independent.co.uk/incoming/article9089048.ece/bi

nary/original/black-death-ala.jpg

Figure 20- Gothic Literature and London map, Edem Makantasis,

2014

Figure 21- Crime Mapping in London, Edem Makantasis, 2014

Figure 22- Unite dmbiance in London, Edem Makantasis, 2014

Figure 23- Potential site for an Architectural intervention, Edem

Makantasis, 2014

52

Edem Makantasis up707998

Architecture Culture and Identity

53

Вам также может понравиться

- PsychogeographyДокумент158 страницPsychogeographyJulia Arthur100% (7)

- The Passion of David Lynch: Wild at Heart in HollywoodОт EverandThe Passion of David Lynch: Wild at Heart in HollywoodРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2)

- Reframing Reality: The Aesthetics of the Surrealist Object in French and Czech CinemaОт EverandReframing Reality: The Aesthetics of the Surrealist Object in French and Czech CinemaОценок пока нет

- Antonioni and Architecture PDFДокумент10 страницAntonioni and Architecture PDFLara MadОценок пока нет

- Sophie Calle PresentationДокумент12 страницSophie Calle PresentationJessica LaneОценок пока нет

- A Beginner's Guide To PsychogeographyДокумент88 страницA Beginner's Guide To Psychogeographybuie_jessicaОценок пока нет

- Airports - Observer ArticleДокумент4 страницыAirports - Observer ArticleSimon SellarsОценок пока нет

- Serial Killings: Fantômas, Feuillade, and The Mass-Culture Genealogy of SurrealismДокумент11 страницSerial Killings: Fantômas, Feuillade, and The Mass-Culture Genealogy of SurrealismhuythientranОценок пока нет

- Stefano Baschiera (Editor), Miriam de Rosa (Editor) - Film and Domestic Space - Architectures, Representations, Dispositif-Edinburgh University Press (2020)Документ256 страницStefano Baschiera (Editor), Miriam de Rosa (Editor) - Film and Domestic Space - Architectures, Representations, Dispositif-Edinburgh University Press (2020)Elmore HawkshawОценок пока нет

- Davis Schneiderman Retaking The Universe William S Burroughs in The Age of GlobalizationДокумент327 страницDavis Schneiderman Retaking The Universe William S Burroughs in The Age of GlobalizationleonardobahamondesОценок пока нет

- View Parade of The Avant-Garde An Anthology of View Magazine 1940-1947 1991 PDFДокумент316 страницView Parade of The Avant-Garde An Anthology of View Magazine 1940-1947 1991 PDFcaptainfreakoutОценок пока нет

- Leeder Murray Cinematic GhostsДокумент321 страницаLeeder Murray Cinematic GhostsLisa KingОценок пока нет

- Flaneur ParisДокумент3 страницыFlaneur ParisSourya MajumderОценок пока нет

- Decapitating Cinema PDFДокумент32 страницыDecapitating Cinema PDFK Kr.0% (1)

- Hypothesis of The Stolen AestheticsДокумент10 страницHypothesis of The Stolen Aestheticschuma_riescoОценок пока нет

- HITCHCOCK - William Rothman - Hitchcock The Murderous Gaze PDFДокумент506 страницHITCHCOCK - William Rothman - Hitchcock The Murderous Gaze PDFvincent souladieОценок пока нет

- PsychogeographyДокумент90 страницPsychogeographybuie_jessica100% (1)

- Multiple Strands and Possible Worlds (By Ruth Pelmutter)Документ9 страницMultiple Strands and Possible Worlds (By Ruth Pelmutter)Jussara AlmeidaОценок пока нет

- Francesca Woodman and The Kantian Sublime IntroДокумент20 страницFrancesca Woodman and The Kantian Sublime IntroKim Lykke JørgensenОценок пока нет

- Anthropologie, Surrealism and DadaismДокумент13 страницAnthropologie, Surrealism and DadaismAndrea AVОценок пока нет

- Dechirures, Joyce MansourДокумент1 страницаDechirures, Joyce MansourpossesstrimaОценок пока нет

- Conceptions and Reworkings of Baroque and Neobaroque in Recent YearsДокумент21 страницаConceptions and Reworkings of Baroque and Neobaroque in Recent YearspuppetdarkОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Critical Perspectives J. G. Ballard - NodrmДокумент170 страницContemporary Critical Perspectives J. G. Ballard - NodrmCarles Morera100% (2)

- Inland Empire: Time Is The EnemyДокумент11 страницInland Empire: Time Is The EnemyAgentEmbryoОценок пока нет

- Occltismm SurrealismДокумент4 страницыOccltismm Surrealismfrancoteves17% (6)

- Surrealist Ghostliness-University of Nebraska Press (2013)Документ320 страницSurrealist Ghostliness-University of Nebraska Press (2013)Diego Mayoral Martín100% (5)

- Guy Debord - Exercise in PsychogeographyДокумент1 страницаGuy Debord - Exercise in PsychogeographyRiccardo MantelliОценок пока нет

- Screen 12 4 Soviet Film 1920sДокумент178 страницScreen 12 4 Soviet Film 1920sAymara Larson RiveroОценок пока нет

- Asian Horror Cinema SyllabusДокумент12 страницAsian Horror Cinema SyllabusangeladenisevОценок пока нет

- Kraus Chris Video Green Los Angeles Art and The Triumph of NothingnessДокумент173 страницыKraus Chris Video Green Los Angeles Art and The Triumph of NothingnessFederica Bueti100% (3)

- After Deren PDFДокумент174 страницыAfter Deren PDFNacho Frutos100% (1)

- Paul Coates (Auth.) - Doubling, Distance and Identification in The Cinema-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2015)Документ227 страницPaul Coates (Auth.) - Doubling, Distance and Identification in The Cinema-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2015)Sofia VictoriaОценок пока нет

- Moma Polke PreviewДокумент51 страницаMoma Polke PreviewBILLANDORN99140% (1)

- A Phantasmagoria of The Female BodyДокумент14 страницA Phantasmagoria of The Female BodyMaite Ibarreche100% (1)

- Retaking The Universe - William S. Burroughs in The Age of Globalization Edited by Davis Schneiderman and Philip WalshДокумент325 страницRetaking The Universe - William S. Burroughs in The Age of Globalization Edited by Davis Schneiderman and Philip WalshMatias Moulin100% (1)

- Experimental Womens Films PDFДокумент433 страницыExperimental Womens Films PDFClaudia CastelánОценок пока нет

- Jean Luc GodardДокумент12 страницJean Luc GodardburkeОценок пока нет

- Notes On The GazeДокумент23 страницыNotes On The GazeBui Tra MyОценок пока нет

- Only Lovers Left AliveДокумент7 страницOnly Lovers Left AliveTeodora CătălinaОценок пока нет

- Artforum Special Film Issue 1970Документ61 страницаArtforum Special Film Issue 1970Mal AhernОценок пока нет

- American Experimental FilmДокумент446 страницAmerican Experimental Film박승열Оценок пока нет

- Claude Cahun (Three Books)Документ393 страницыClaude Cahun (Three Books)Mark A. FosterОценок пока нет

- Polysexuality - Semiotext (E)Документ306 страницPolysexuality - Semiotext (E)Jae Koo ZulОценок пока нет

- Sex Drive (Mark Dery Interviews J.G. Ballard and David Cronenberg For 21.c Magazine)Документ14 страницSex Drive (Mark Dery Interviews J.G. Ballard and David Cronenberg For 21.c Magazine)Mark Dery100% (1)

- WholeДокумент353 страницыWholemasichkinkОценок пока нет

- George Baker Ed 2003 James Coleman October Books MIT Essays by Raymond Bellour Benjamin H D Buchloh Lynne Cooke Jean Fisher Luke Gib PDFДокумент226 страницGeorge Baker Ed 2003 James Coleman October Books MIT Essays by Raymond Bellour Benjamin H D Buchloh Lynne Cooke Jean Fisher Luke Gib PDFAndreea-Giorgiana MarcuОценок пока нет

- BARRADAS JORGE, Nuno The Films of Pedro Costa, Producing and ConsumingДокумент185 страницBARRADAS JORGE, Nuno The Films of Pedro Costa, Producing and ConsumingAndré AlexandreОценок пока нет

- Home Stewart Neoism Plagiarism and PraxisДокумент209 страницHome Stewart Neoism Plagiarism and PraxisRanko TravanjОценок пока нет

- Walking in Life, Art and Science: A Few ExamplesДокумент64 страницыWalking in Life, Art and Science: A Few ExamplesGilles MalatrayОценок пока нет

- Art and Archive 1920-2010Документ18 страницArt and Archive 1920-2010Mosor VladОценок пока нет

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Cinema As A Ghost MediumДокумент10 страницApichatpong Weerasethakul: Cinema As A Ghost Mediummegnluke100% (1)

- Lauretis - Aesthetic and Feminist Theory PDFДокумент11 страницLauretis - Aesthetic and Feminist Theory PDFJeremy DavisОценок пока нет

- Guide To Lost-Flaneur GuideДокумент19 страницGuide To Lost-Flaneur GuideLeOn Wzz 众Оценок пока нет

- Blood OrgiesДокумент120 страницBlood OrgiesEmina Isic Zovkic100% (1)

- Japanese Horror - Oldboy and Audition Cinema of CruletyДокумент340 страницJapanese Horror - Oldboy and Audition Cinema of CruletyShaul RechterОценок пока нет

- Photography and Surrealism. Sexuality Colonialism and Social Dissent PDFДокумент283 страницыPhotography and Surrealism. Sexuality Colonialism and Social Dissent PDFMiriam Rejas del Pino100% (6)

- Alternative Modernities in French Travel Writing: Engaging Urban Space in London and New York, 18511986От EverandAlternative Modernities in French Travel Writing: Engaging Urban Space in London and New York, 18511986Оценок пока нет

- Suburban Urbanities: Suburbs and the Life of the High StreetОт EverandSuburban Urbanities: Suburbs and the Life of the High StreetРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- Imaging the City: Art, Creative Practices and Media SpeculationsОт EverandImaging the City: Art, Creative Practices and Media SpeculationsОценок пока нет

- Department of English and American StudiesДокумент45 страницDepartment of English and American StudiesKhushnood AliОценок пока нет

- Sermon On 12/01/2019 - Advent 1Документ2 страницыSermon On 12/01/2019 - Advent 1TimmОценок пока нет

- Haxan - GRADEDДокумент3 страницыHaxan - GRADEDMatt HerbertzОценок пока нет

- Life of Pi Questions Part 1Документ3 страницыLife of Pi Questions Part 1api-238242808Оценок пока нет

- Hyperion PDFДокумент342 страницыHyperion PDFKarlОценок пока нет

- The 36 Chapter of Natya Shastra - Kolkata International Dance FestivalДокумент4 страницыThe 36 Chapter of Natya Shastra - Kolkata International Dance Festival(KIDF) Kolkata International Dance FestivalОценок пока нет

- English Tenses Test 6 English Tenses in The Reported Speech and Passive Voice 1. Change The Direct Speech Into The Reported SpeechДокумент2 страницыEnglish Tenses Test 6 English Tenses in The Reported Speech and Passive Voice 1. Change The Direct Speech Into The Reported SpeechmariusborzaОценок пока нет

- Using Multicultural Children S Literature To Teach Diverse PerspectivesДокумент7 страницUsing Multicultural Children S Literature To Teach Diverse PerspectivesSimge CicekОценок пока нет

- Bullock yДокумент10 страницBullock ySuman PrasadОценок пока нет

- Plays With MonologuesДокумент16 страницPlays With MonologuesCaitlin McDonnell89% (9)

- Script Details: 3 Little PigsДокумент3 страницыScript Details: 3 Little PigsghionulОценок пока нет

- 21st Century 2nd Summative TestДокумент2 страницы21st Century 2nd Summative TestNINA100% (1)

- EurasianStudies 0110 EPA01521Документ186 страницEurasianStudies 0110 EPA01521Iulia CindreaОценок пока нет

- Coptic QuillДокумент4 страницыCoptic QuilllouishaiОценок пока нет

- The TemptationДокумент15 страницThe TemptationPolygondotcomОценок пока нет

- JRR2 PreviewДокумент4 страницыJRR2 PreviewDarlington RichardsОценок пока нет

- Dear Brother in Christ....Документ3 страницыDear Brother in Christ....Jesus LivesОценок пока нет

- 1 Stylistics (2) Master 2Документ47 страниц1 Stylistics (2) Master 2Safa BzdОценок пока нет

- T. S. Eliot's Forgotten "Poet of Lines," Nathaniel WanleyДокумент7 страницT. S. Eliot's Forgotten "Poet of Lines," Nathaniel WanleyissamagicianОценок пока нет

- Lincoln's Imagination - Scribner's - Aug - 1979Документ6 страницLincoln's Imagination - Scribner's - Aug - 1979RASОценок пока нет

- Microeconomics Theory and Applications With Calculus 4th Edition Perloff Solutions ManualДокумент36 страницMicroeconomics Theory and Applications With Calculus 4th Edition Perloff Solutions Manualsiphilisdysluite7xrxc100% (23)

- The Noble Eightfold PathДокумент8 страницThe Noble Eightfold Path28910160Оценок пока нет

- Archaeological Institute of AmericaДокумент15 страницArchaeological Institute of AmericaGurbuzer2097Оценок пока нет

- Spainculture Esta Breve Tragedia de La Carne by Angelica LiddellДокумент2 страницыSpainculture Esta Breve Tragedia de La Carne by Angelica LiddellDavid RuanoОценок пока нет

- სამართლის ჟურნალი,სტატიაა PDFДокумент412 страницსამართლის ჟურნალი,სტატიაა PDFkateОценок пока нет

- Desdemona and BiancaДокумент5 страницDesdemona and Biancamahima97Оценок пока нет

- Lendo: A Kind Goblins BirdДокумент7 страницLendo: A Kind Goblins BirdKatherine S.Оценок пока нет

- Role of Ramayana in Transformation of The PersonalДокумент7 страницRole of Ramayana in Transformation of The PersonalPea KayhОценок пока нет

- Daily Activities and HobbiesДокумент3 страницыDaily Activities and HobbiesHụê MinhОценок пока нет

- No Coptic JesusДокумент6 страницNo Coptic JesusuyteuyiuyouyttyОценок пока нет