Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

20 Escritor vs. IAC

Загружено:

TurboyNavarroАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

20 Escritor vs. IAC

Загружено:

TurboyNavarroАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

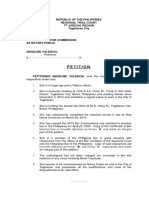

G.R. No.

71283 November 12, 1987

MIGUEL ESCRITOR, JR., ANGEL ESCRITOR, RAMON

ESCRITOR, JUANA ESCRITOR, CONCORDIA ESCRITOR,

IRENE ESCRITOR, MATILDE ESCRITOR, MERCEDES

ESCRITOR, HEIRS OF LUIS ESCRITOR, represented by

RUPERTO ESCRITOR, HEIRS OF PEDO ESCRITOR,

represented by SUSANA VILLAMENA, LINA ESCRITOR,

WENDELINA ESCRITOR, ALFREDO ESCRITOR, SUSANA

ESCRITOR and CARMEN ESCRITOR, petitioners,

vs.

INTERMEDIATE APPELLATE COURT and SIMEON

ACUNA, respondents.

GANCAYCO, J.:

This is a petition for review on certiorari seeking the reversal of

the decision of the Intermediate Appellate Court in AC-G.R. No.

CV-01264-R entitled "Simeon Acuna vs. Miguel Escritor, Jr., et

al," a case which originated from the Court of First Instance of

Quezon.

The record of the case discloses the following facts:

Lot No. 2749, located at Atimonan, Quezon, was the subject of

cadastral proceedings in the Court of First Instance of Quezon,

Gumaca Branch, Miguel Escritor, as claimant, filed an answer

thereto declaring his ownership over the lot alleging that he

acquired it by inheritance from his deceased father. 1 As

required, a notice of hearing was duly published, after which an

order of general default was entered. 2 The lot having become

uncontested, only Miguel Escritor appeared in order to adduce

his evidence of ownership.

On February 16, 1971 or thirteen years after the disputed

decision was rendered, the Court adjudicated Lot No. 2749 in

favor of respondent Acuna, ordering petitioners to vacate the

land. 7 A writ of possession was later issued and petitioners

voluntarily gave up their possession. 8

More than four years later, or on October 13, 1975 respondent

Acuna filed with the same Court in Civil Case No. 1138-G, a

complaint for recovery of damages against petitioners for the

fruits of lot No. 2749 which was allegedly possessed by the latter

unlawfully for thirteen years. According to respondent Acua, the

registration of the said lot was effectuated by the deceased

claimant Escritor through fraud, malice, and misrepresentation.

The lower court, however, rendered a decision dismissing

Acua's complaint for damages, finding that though petitioners

enjoyed the fruits of the property, they were in good faith

possessing under a just title, and the cause of action, if there was

any, has already prescribed. 9

On Appeal to the Intermediate Appellate Court, the judgment of

the lower court was reversed in a decision promulgated on

October 31, 1984, the dispositive portion of which reads:

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing

considerations, the decision appealed from is

hereby REVERSED and set aside and another

one entered herein, ordering the defendantsappellees jointly and severally (a) to pay the

plaintiff- appellant the sum of P10,725.00

representing the value of the fruits appellees

received for the 13 years they have been in

unlawful possession of the land subject-matter;

(b) to pay plaintiff-appellant the sum of

P3,000.00 for attorney's fees and expenses of

litigation, and (c) to pay the costs.

Hence this petition.

On May 15, 1958, the Court rendered a decision in the

abovementioned case, Cadastral Case No. 72, adjudicating the

lot with its improvements in favor of claimant Escritor and

confirming his title thereto. 3Immediately thereafter, Escritor took

possession of the property. On July 15, 1958, the Court, in an

Order, directed the Chief of the General Land Registration Office

to issue the corresponding decree of registration in favor of

Escritor, the decision in Cadastral Case No. 72 having become

final. 4

On August 2, 1958, Simeon S. Acuna, the herein respondent, filed

a petition for review of the above-mentioned decision contending

that it was obtained by claimant Escritor through fraud and

misrepresentation. 5 The petition was granted on July 18, 1960

and a new hearing was set for September 13, 1960. 6 While the

proceedings were going on, claimant Escritor died. His heirs, the

petitioners in this case, took possession of the property.

The main issue that has to be resolved in this case is whether or

not petitioners should be held liable for damages.

Contrary to the finding of the trial court, the Intermediate

Appellate Court made the pronouncement that petitioners were

possessors in bad faith from 1958 up to 1971 and should be held

accountable for damages. This conclusion was based on the

statement of the cadastral court in its August 21, 1971 decision,

readjudicating Lot No. 2749 to respondent Simeon Acuna, that

"Miguel Escritor forcibly took possession of the land in May,

1958, and benefited from the coconut trees thereon. 10 The

Intermediate Appellate Court observed that on the basis of the

unimpeached conclusion of the cadastral court, it must be that

the petitioners have wrongfully entered possession of the

land. 11 The Intermediate Appellate Court further explains that

as such possessors in bad faith, petitioners must reimburse

respondent Acuna for the fruits of the land they had received

during their possession. 12

We cannot affirm the position of the Intermediate Appellate

Court. It should be remembered that in the first decision of the

cadastral court dated May 15, 1958, Lot No. 2749 was

adjudicated in favor of claimant Escritor, petitioners'

predecessor-in-interest. In this decision, the said court found to

its satisfaction that claimant Escritor acquired the land by

inheritance from his father who in turn acquired it by purchase,

and that his open, public, continuous, adverse, exclusive and

notorious possession dated back to the Filipino-Spanish

Revolution. 13 It must also be recalled that in its Order for the

issuance of decrees dated July 15, 1958, the same Court

declared that the above-mentioned decision had become final.

Significantly, nowhere during the entire cadastral proceeding did

anything come up to suggest that the land belonged to any

person other than Escritor.

On the basis of the aforementioned favorable judgment which

was rendered by a court of competent jurisdiction, Escritor

honestly believed that he is the legal owner of the land. With this

well-grounded belief of ownership, he continued in his possession

of Lot No. 2749. This cannot be categorized as possession in bad

faith.

As defined in the law, a possessor in bad faith is one in

possession of property knowing that his title thereto is

defective. 14 Here, there is no showing that Escritor knew of any

flaw in his title. Nor was it proved that petitioners were aware

that the title of their predecessor had any defect.

Nevertheless, assuming that claimant Escritor was a possessor in

bad faith, this should not prejudice his successors-in-interest,

petitioners herein, as the rule is that only personal knowledge of

the flaw in one's title or mode of acquisition can make him a

possessor in bad faith, for bad faith is not transmissible from one

person to another, not even to an heir. 15 As Article 534 of the

Civil Code explicitly provides, "one who succeeds by hereditary

title shall not suffer the consequences of the wrongful possession

of the decedent, if it is not shown that he was aware of the flaws

affecting it; ..." The reason for this article is that bad faith is

personal and intransmissible. Its effects must, therefore, be

suffered only by the person who acted in bad faith; his heir

should not be saddled with such consequences. 16

Under Article 527 of the Civil Code, good faith is always

presumed, and upon him who alleges bad faith on the part of a

possessor rests the burden of proof. If no evidence is presented

proving bad faith, like in this case, the presumption of good faith

remains.

Respondent Acuna, on the other hand, bases his complaint for

damages on the alleged fraud on the part of the petitioners'

predecessor in having the land registered under his (the

predecessor's) name. A review of the record, however, does not

indicate the existence of any such fraud. It was not proven in the

cadastral court nor was it shown in the trial court.

Lot No. 2749 was not awarded to Escritor on the basis of his

machinations. What is clear is that in the hearing of January 22,

1958, the Court permitted Escritor to adduce his evidence of

ownership without opposing evidence as the lot had become

uncontested. 17 Respondent Acuna himself failed to appear in

this hearing because of a misunderstanding with a

lawyer.18 There is no finding that such failure to appear was

caused by petitioners in this case. On the contrary, all the

requirements of publication were followed. Notice of hearing was

duly published. Clearly then, the allegation of fraud is without

basis.

Respondent having failed to prove fraud and bad faith on the

part of petitioners, We sustain the trial court's finding that

petitioners were possessors in good faith and should, therefore,

not be held liable for damages.

With the above pronouncement, the issue of prescription of

cause of action which was also presented need not be passed

upon.

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED and the decision appealed

from is hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE and another decision is

rendered dismissing the complaint. No pronouncement as to

costs.

SO ORDERED.

9 Page 11, Record on Appeal.

Teehankee, C.J., Narvasa, Cruz and Paras, JJ., concur.

l0 Page 26, Rollo.

11 Pages 26-27, Rollo.

Footnotes

12 Page 27, Rollo.

1 Exhibit "A". Cadastral Answer.

2 Exhibit "B". decision in Cadastral Case. No.

72 dated May 15, 1958.

3 Ibid.

4 Exhibit "C", Order for the Issuance of Decrees

in cadastral cases.

5 Exhibit "D", Petition.

6 Exhibit "E", Order in Cadastral Case No. 72.

7 Exhibit "F", Decision in Cadastral Case No.

72.

8 Exhibit "H", Writ of Possession.

13 Exhibit "B", Decision in Cadastral Case No.

72 dated May 15, 1958.

14 Art. 526, New Civil Code.

15 Tolentino, Civil Code of the Philippines, Vol.

II, 1983 Ed., p. 223; Sotto vs. Enage, (CA), 43

Off. Gaz. 5057.

16 Tolentino, Civil Code of the Philippines, Vol.

11, 1983 Ed., p. 234.

17 Exhibit "B", Decision in Cadastral Case No.

72 dated May 15,1958.

18 Exhibit "E", Order dated July 18, 1960,

Cadastral Case No. 72.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- DurhamДокумент23 страницыDurhamJessica McBride0% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Genuino vs. de Lima (Judicial Department-Judicial Power-Digest)Документ3 страницыGenuino vs. de Lima (Judicial Department-Judicial Power-Digest)Concon FabricanteОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 175763 - Heirs of Spouses Tanyag v. Gabriel PDFДокумент12 страницG.R. No. 175763 - Heirs of Spouses Tanyag v. Gabriel PDFFranco AguiluzОценок пока нет

- 53 Meralco v. Lim - Capellan, GlecieДокумент2 страницы53 Meralco v. Lim - Capellan, GlecieFroilan Villafuerte FaurilloОценок пока нет

- Digest-Francisco v. NLRC 170087Документ3 страницыDigest-Francisco v. NLRC 170087TurboyNavarro100% (1)

- Av Petition For Notarial CommissionДокумент3 страницыAv Petition For Notarial CommissionTurboyNavarroОценок пока нет

- SLB Tax Pre Week Material 2018 Bar 11072018Документ15 страницSLB Tax Pre Week Material 2018 Bar 11072018Jade LorenzoОценок пока нет

- Store Quality Audit ChecklistДокумент6 страницStore Quality Audit ChecklistTurboyNavarroОценок пока нет

- Filipinas Colleges Vs Timbang-DigestДокумент2 страницыFilipinas Colleges Vs Timbang-DigestKarissa TolentinoОценок пока нет

- Balila Vs IACДокумент3 страницыBalila Vs IACNath AntonioОценок пока нет

- The Law Firm of Raymundo A. Armovit vs. CAДокумент2 страницыThe Law Firm of Raymundo A. Armovit vs. CAJhoi MateoОценок пока нет

- DigestsДокумент2 страницыDigestsTurboyNavarro100% (1)

- Shiba Inu Captions 1 UsedДокумент2 страницыShiba Inu Captions 1 UsedTurboyNavarroОценок пока нет

- IHD Questions TempДокумент5 страницIHD Questions TempTurboyNavarroОценок пока нет

- Labradoodle Captions 1Документ1 страницаLabradoodle Captions 1TurboyNavarroОценок пока нет

- Lovely Workout SchedДокумент1 страницаLovely Workout SchedTurboyNavarroОценок пока нет

- Evidence Cases AssignmentsДокумент77 страницEvidence Cases AssignmentsTurboyNavarroОценок пока нет

- Case List For Sales: Atty. ArcamoДокумент193 страницыCase List For Sales: Atty. ArcamoTurboyNavarroОценок пока нет

- Turbo3 Tarp SampleДокумент1 страницаTurbo3 Tarp SampleTurboyNavarroОценок пока нет

- United Cadiz Sugar Farmers Association Multi-Purpose Cooperative v. CommissionerДокумент6 страницUnited Cadiz Sugar Farmers Association Multi-Purpose Cooperative v. CommissionerEryl YuОценок пока нет

- Leslie Okol Vs Slimmers World International Et. Al. - gr160146 - December 11, 2009Документ3 страницыLeslie Okol Vs Slimmers World International Et. Al. - gr160146 - December 11, 2009BerniceAnneAseñas-ElmacoОценок пока нет

- (HC) Bousamra vs. Sisto, Et Al - Document No. 4Документ2 страницы(HC) Bousamra vs. Sisto, Et Al - Document No. 4Justia.comОценок пока нет

- Jesus Ruiz-Rodriguez v. Dr. Wallace A. Colberg-Comas, 882 F.2d 15, 1st Cir. (1989)Документ5 страницJesus Ruiz-Rodriguez v. Dr. Wallace A. Colberg-Comas, 882 F.2d 15, 1st Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Memorial On Behalf of The Petitioner: Astha Mishra Roll No. 565 Sem: VI "BДокумент21 страницаMemorial On Behalf of The Petitioner: Astha Mishra Roll No. 565 Sem: VI "BAastha MishraОценок пока нет

- Pahud v. Court of Appeals 597 SCRA 13 2009Документ3 страницыPahud v. Court of Appeals 597 SCRA 13 2009Kent UgaldeОценок пока нет

- 01 Planas V GilДокумент23 страницы01 Planas V GileieipayadОценок пока нет

- CPC ProjectДокумент23 страницыCPC ProjectManish PalОценок пока нет

- Bitonio V CoaДокумент24 страницыBitonio V Coamarjorie requirmeОценок пока нет

- Alternative Dispute Resolution LawДокумент10 страницAlternative Dispute Resolution LawGerald SuarezОценок пока нет

- Flavius-Cristian MarcauДокумент4 страницыFlavius-Cristian MarcauDramo LamaОценок пока нет

- Darton LTD V Hong Kong Island Development LTD (2002) 1 HKLRD 145Документ3 страницыDarton LTD V Hong Kong Island Development LTD (2002) 1 HKLRD 145Nicole YauОценок пока нет

- Villena v. RupisanДокумент13 страницVillena v. Rupisancarla_cariaga_2Оценок пока нет

- Soft On CrimeДокумент77 страницSoft On CrimeAlvin Gonzales InaleОценок пока нет

- Lico V ComelecДокумент5 страницLico V ComelecNerissa BelloОценок пока нет

- Vda. de Jacob v. CA, GR 135216Документ8 страницVda. de Jacob v. CA, GR 135216Peter RojasОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 197174 September 10, 2014 FRANCLER P. ONDE, Petitioner, The Office of The Local Civil Registration of Las Piñas City, RespondentДокумент6 страницG.R. No. 197174 September 10, 2014 FRANCLER P. ONDE, Petitioner, The Office of The Local Civil Registration of Las Piñas City, RespondentKaren Sheila B. Mangusan - DegayОценок пока нет

- Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited Vs Malvinder Mohan Singh and Ors Coporate GovernanceДокумент5 страницDaiichi Sankyo Company Limited Vs Malvinder Mohan Singh and Ors Coporate GovernanceBeebee ZainabОценок пока нет

- Land Registration Authority vs. Lanting Security and Watchman AgencyДокумент9 страницLand Registration Authority vs. Lanting Security and Watchman AgencyChaОценок пока нет

- Pacete vs. Commission On AppointmentsДокумент4 страницыPacete vs. Commission On AppointmentsDarl YabutОценок пока нет

- Arlene S. Fischer, a Minor by Her Father, in No. 18961 v. Uwe M. Buehl Alvin H. Frankel, Administrator of the Estate of Charlotte K. Fischer, Deceased, in No. 18962 v. Uwe M. Buehl, 450 F.2d 950, 3rd Cir. (1971)Документ2 страницыArlene S. Fischer, a Minor by Her Father, in No. 18961 v. Uwe M. Buehl Alvin H. Frankel, Administrator of the Estate of Charlotte K. Fischer, Deceased, in No. 18962 v. Uwe M. Buehl, 450 F.2d 950, 3rd Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- NotingДокумент254 страницыNotingToqeer Raza100% (1)